Abstract

We examine the impact of a firm’s innovation strategy on its disclosure policy. Using a sample of innovation-intensive U.S. firms from 1992 to 2012, we find that firms with higher intensity of exploratory (exploitative) innovation are more (less) inclined to issue management earnings forecasts. These forecasts are generally less (more) optimistic, accurate and precise. We also find that exploration-oriented firms issue more earnings forecasts in order to avoid disclosing proprietary information about their innovation activities. They tend to issue more conservative forecasts in order to avoid large stock price decline. Overall, exploration-oriented firms have a more opaque information environment as manifested in higher analyst earnings forecast error and greater forecast dispersion. Our findings suggest that knowledge-intensive firms appear to incorporate innovation strategy in developing their disclosure policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As competition intensifies and the pace of change accelerates, firms need to continuously renew themselves and seek new sources of growth by investing in innovation. While knowledge-intensive firms are all committed to investing more resources into this activity, there is considerable variation in their innovation strategy. The management literature has identified two generic types of innovation: exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation (Levinthal and March 1993; McGrath 2001; Benner and Tushman 2002). Firms that pursue exploratory innovation are constantly in search of new technologies or approaches, hoping to achieve breakthrough inventions and the “next big thing”. Exploitation-oriented firms, on the other hand, primarily build on improvements and refinements of current skills and processes that lead to incremental product changes (Holmqvist 2004; Levinthal and March 1993; Amason et al. 2006). As succinctly summarized by March (1991), the distinction between “exploration of new possibilities” and “exploitation of old certainties” is associated with firm behavior that has significant implications for a firm’s underlying earnings stream and information environment (He and Wong 2004).

In this study, we are interested in how a firm’s choice of innovation strategy affects its disclosure practices. For publicly traded companies, communicating with market participants and maintaining a transparent information environment are important considerations as they directly affect the cost of capital (Lambert et al. 2007), which is a key source of input into innovation activities. Exploration and exploitation are each associated with a set of features that may influence corporate disclosure practices. Exploratory firms that are able to successfully innovate at a breakthrough level can increase the likelihood that they will dominate the market and build a sustainable competitive edge. However, exploratory activities are characterized by high failure and the associated returns are “uncertain, distant, and often negative” (March 1991), which increases the volatility of the firm’s underlying earnings stream. Moreover, given the novel and proprietary nature of exploration, it creates significant knowledge and information gap with firm outsiders, which makes it hard for market participants to accurately assess the value of such innovation and its contribution to future firm performance (Rindova and Petkova 2007; Kaplan and Tripsas 2008). Exploitation, in contrast, exhibits returns that are more proximate and predictable (He and Wong 2004). Because exploitation emphasizes on extending currently successful approaches, there is more information about this type of innovation (e.g., information about past track record or prior performance data). As a result, exploitation-oriented firms face less severe information asymmetry and knowledge gap with outsiders. However, a downside of exploitation is that by limiting innovation to incremental improvements, exploitative firms may fail to create significant economic rents or step changes.

We begin to examine the relationship between a firm’s innovation strategy and its disclosure practices by focusing on management earnings forecasts because they are the most common form of voluntary disclosure for a firm to communicate future performance projections to market participants (Pownall and Waymire 1989; King et al. 1990; Skinner 1994, 1997; Frankel et al. 1995; Coller and Yohn 1997; Noe 1999). Earnings forecasts also incorporate managers’ expectation about how much value the firm can extract from current innovation projects. Ex ante it is not clear whether firms with higher exploratory intensity are more willing to issue management forecasts. On the one hand, management-provided disclosure is particularly valuable in the cases of severe information asymmetry and performance unpredictability. So exploratory firms may have greater incentives to provide earnings forecasts. On the other hand, however, exploratory firms may be reluctant to disclose future information given higher proprietary information costs (Verrecchia 1983; Bamber and Cheon 1998; Li 2010).Footnote 1 Given these opposing incentives and concerns, the relationship between innovation strategy and management forecast behavior is essentially an open, empirical question.

We measure innovation strategy using empirical constructs that have been developed in prior research based on a firm’s patent information (e.g., Balsmeier et al. 2017; Custódio et al. 2015; Katila and Ahuja 2002; Benner and Tushman 2003). Specifically, the extent to which a firm adopts an exploratory innovation strategy Explore, is calculated as the number of exploratory patents filed in a given year divided by the number of all patents filed by the firm in the same year. A higher value of Explore indicates that the firm is more exploration-oriented. In contrast, we define the extent to which a firm adopts an exploitative innovation strategy Exploit, as the number of exploitative patents filed in a given year divided by the number of all patents filed by the firm in the same year.Footnote 2

Using a sample of publicly-traded U.S. firms over the period of 1992–2012, we find a positive (negative) relationship between exploratory (exploitation) innovation intensity and the likelihood of issuing management earnings forecasts. Conditional on issuing a forecast, we further examine how innovation strategy affects the properties of these forecasts, including forecast optimism, accuracy, and precision. Consistent with the notion that innovation projects entail significant failure risk and the associated outcome can be highly unpredictable, we find that earnings forecasts issued by exploratory firms are generally less optimistic, less accurate, and less precise.

One challenge in interpreting our baseline findings is that the association between corporate innovation strategy and management forecasts could be driven by unobservable characteristics that are related to both constructs. There is also a reverse causality concern that a firm’s choice of innovation strategy is affected by its disclosure policy. We attempt to address these issues in two ways. Our first approach is the two-stage least squares (2SLS) analysis. Our instrumental variable, InventorMobility, is defined as the difference between the natural logarithm of one plus the inflow of inventors and the natural logarithm of one plus the outflow of inventors in a given year.Footnote 3 Findings from the 2SLS analysis are consistent with our baseline results.

Our second approach to mitigating the endogeneity concern is to examine changes in corporate innovation strategy and corresponding changes in management forecast behavior. We find that changes in exploration (exploitation) intensity positively (negatively) relate to changes in the likelihood of issuing forecasts, but negatively (positively) relate to changes in the forecast optimism and accuracy. Taken together, our findings suggest that exploration-oriented firms are more willing to provide forward-looking earnings guidance. However, because of greater uncertainty about future payoffs from exploratory innovation, these forecasts are generally less optimistic, less accurate and precise. We find opposite results for exploitation-oriented firms.

It is somewhat puzzling that exploratory firms are more inclined to issue management earnings forecasts, despite greater difficulty in making these forecasts accurate and precise given the highly uncertain nature of exploratory innovation. We offer one plausible explanation for such behavior, that is, mangers of exploratory firms may choose to issue more earnings forecasts to satisfy the information demand of capital market participants in order to avoid disclosing more proprietary information about their innovation projects. To test this conjecture, we obtain information on the disclosure of R&D expenditures from Compustat (Koh and Reeb 2015), and search the LexisNexis News Wires for disclosure of non-financial information related to innovation activities made by our sample firms. Empirical evidence suggests that exploratory firms are less likely to report R&D expenditures. They are also less willing to disclose additional information about their innovation activities, especially information related to the strategy and progress of innovation. However, the effect is less pronounced for firms with large institutional ownership as institutional investors possess superior ability than retail investors in understanding the value of patents. As such, they are more likely to (successfully) demand the disclosure of such information. We generally find opposite results for exploitative firms.

We also attempt to explore why exploratory firms issue more conservative (i.e., pessimistically biased) earnings forecasts. We conjecture that due to the highly uncertain nature and high failure rate of exploratory innovation, the probability that exploratory firms incur unsatisfactory earnings performance is high. Moreover, because investors face higher information gap with exploratory firms, they rely more heavily on management provided guidance in making investment decision. So if managers of exploratory firms issue overly-optimistic forecasts to hype up investors’ expectation and later miss their forecasts, they may lose credibility and investors may be disappointed more and respond with a greater decline in stock price, which is undesirable for the firm. So managers of exploratory firms may prefer more conservative forecasts to guide down investors’ expectation in order to avoid large disappointment and stock price decline. To test this conjecture, we examine market reaction to management forecast error and the interaction effect with exploration and exploitation intensity, respectively. We find that market reaction to positive management forecast error (i.e., actual performance is below manager’s expectation) is greater for exploratory firms.

Finally, we examine the impact of corporate innovation strategy on the firm’s overall information environment, as measured by analyst forecast accuracy and degree of forecast dispersion among them. We find that higher exploratory (exploitative) intensity is associated with higher (lower) analyst forecast error and greater dispersion, suggesting that these firms appear to have a more (less) opaque information environment.

Our study contributes to the literature on management forecasts and provides evidence that innovation strategy is an important determinant of corporate disclosure policy. As Hirst et al. (2008) conclude in their review of the literature on management forecasts: “…managers’ choice of forecast characteristics appears to be the least understood (both in terms of theory and research) even though it is the component over which managers have the most control.” Several prior studies examined investment into innovation activities (i.e., R&D expenditure) and its impact on disclosure practice. For example, Jones (2007) studies voluntary disclosure in R&D intensive industries. Barron et al. (2002) examines technology intangibles and analyst forecast. However, these studies implicitly assume that how a firm’s use of R&D resources or technology intangibles based on different strategy have an equal impact on disclosure or analyst behavior. In contrast, we highlight that innovation strategy has a direct and significant impact on corporate disclosure behavior.

Our study also contributes to the growing literature on innovation (Chen et al. 2016; Guo and Zhou 2016; Jia and Tian 2016; Adhikari and Agrawal 2016; Hsu et al. 2015; Gao et al. 2006). The choice between exploratory and exploitative innovation is an important strategic decision that has implications for multiple aspects of corporate practices and performance. Prior work has documented positive effects of exploratory innovation on new product development and revenue growth (e.g., Katila and Ahuja 2002; Uotila et al. 2009), but little is known about its impact on corporate disclosure practices. We provide evidence on this issue.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and presents descriptive statistics. Section 4 reports baseline empirical results. Section 5 addresses the endogeneity issues and provide results of additional analyses. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1 Corporate innovation strategy

Since the seminal work of March (1991), the management literature has identified two distinct strategies in organizational learning trajectories that pertain to innovation activities: exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation (Levinthal and March 1993; McGrath 2001; Benner and Tushman 2002; Smith and Tushman 2005). Exploration implies firm behaviors characterized by experimentation and risk-taking (Cheng and Van de Ven 1996; March 1991). Such innovation involves experimenting with new technologies or approaches, and continued efforts to achieve breakthrough inventions. Exploitation, in contrast, implies firm behaviors characterized by refinement and efficiency (March 1991). Exploitative innovation involves incremental changes to existing products or approaches. These changes are primarily aimed at protecting market share and generating returns from currently successful approach (Manso 2011).

A firm’s choice of innovation strategy has significant implications for its underlying earnings stream and information environment (He and Wong 2004). Exploration, by its nature, is associated with more substantial success as well as failure. The associated returns are systematically less certain, more variable and distant in time, which makes the firm’s underlying earnings stream more volatile and less predictable. In contrast, exploitation is associated with greater certainty of short-term success, therefore the future performance of exploitative firms is relatively more stable and predictable (March 1991).

Exploration and exploitation also differ in the extent of information and knowledge gap with firm outsiders. Exploratory innovation involves the departure from existing knowledge and experiment with new technologies or approaches. These breakthrough inventions—which have not been seen in the market before—likely impose a larger knowledge and information gap between the firm and outside stakeholders. Exploitative inventions, on the other hand, rely on existing capabilities and knowledge. They are more familiar to outsiders and have past track record or performance data which makes it easier for outsiders to understand and assess the value of these inventions and their contributions to the firm’s future performance (Rindova and Petkova 2007; Kaplan and Tripsas 2008).

Exploration and exploitation also differ in terms of proprietary information costs. Henderson (1999) classifies innovation strategies into proprietary versus standards-based strategies, and suggests that the former may be more related to exploration while the latter may be more related to exploitation. Exploration involves internally-developed, firm-specific new knowledge and therefore is more proprietary in nature. Successful exploration can generate explosive growth in major new categories of products and services, and create greater competitive advantage than incremental innovations. Therefore, exploratory firms may have stronger strategic incentives to withhold disclosure in order to protect their competitive edge and avoid unwanted competition.

One stream of management literature studies the determinants of corporate choice between exploratory and exploitative innovation strategy. It has been shown that firms are less (more) likely to engage in exploratory (exploitative) innovation when their shareholders/managers are myopic or risk-averse (Levinthal and March 1993; Smith and Tushman 2005), when they pursue economies of scale (Crossan et al. 1999), when their innovative activities are more likely to be subjects of imitation (Cohen and Levinthal 1994), or when their environment appears to be less volatile (McGrath 2001). Prior research also recognizes that firms rarely choose exclusively between exploration and exploitation strategy. In fact, March (1991) and Levinthal and March (1993), among others, suggest that firms tend to be ambidextrous, that is, they “engage in sufficient exploitation to ensure its current viability and, at the same time, devote enough energy to exploration to ensure its future viability” (Levinthal and March 1993, p.105). Therefore, instead of using a dichotomous variable for innovation strategy (i.e., exploration vs. exploitation), we focus on the intensity of exploration and exploitation, that is, the extent to which a firm leans towards an exploration-oriented or exploitation-oriented innovation strategy.

2.2 Innovation strategy and management earnings forecasts

We develop four hypotheses regarding how corporate innovation strategy affects management forecast practice. The first hypothesis pertains to the likelihood of issuing a forecast. For publicly traded companies, the supply of and the demand for management forecasts is significantly influenced by capital market considerations, with managers issuing forecasts to reduce the level of information asymmetry with external stakeholders (Ajinkya and Gift 1984; Verrecchia 2001). Lower information asymmetry is desirable because it is associated with higher liquidity (Diamond and Verrecchia 1991) and lower cost of capital (Leuz and Verrecchia 2000). For knowledge-intensive firms, the ability to raise low-cost external funds when needed is an important consideration since innovation activities require large and continued capital commitment. As discussed earlier, firms pursuing an exploration strategy have intrinsically higher information and knowledge gap with firm outsiders, so management forecasts may be more valuable and useful to investors in such cases. So we expect these firms to have stronger incentives to provide voluntary forecasts.

Although there are benefits to voluntarily disclosing more corporate information, there are also costs. Economic theory suggests that proprietary costs are an important deterrent to full voluntary disclosure (Verrecchia 1983; Wagenhofer 1990; Bamber and Cheon 1998; Li 2010). Releasing management estimates of future earnings can reveal valuable information about how much gain the firm is expecting to extract from undergoing innovation efforts. Such information could be used by competitors to make entry or exit decisions that can erode the firm’s competitive edge and invite unwanted competition or imitation. Disclosure made by exploratory firms is arguably more valuable to competitors because there is little public information available about this type of innovation (Rindova and Petkova 2007; Kaplan and Tripsas 2008). Competitors can act on such firm-provided information to determine their response to the disclosing firm’s innovation strategy which may erode the firm’s competitive edge. As a result, exploratory firms may choose to refrain from making earnings guidance. Bamber and Cheon (1998) and Ali et al. (2014), among others, show that industry concentration, a common proxy for proprietary costs, is associated with a lower likelihood of issuing management earnings forecasts.

In summary, the relation between innovation strategy and the propensity of issuing management forecasts is unclear ex ante. Therefore, we propose an un-directional hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (issuance)

Exploratory (Exploitative) innovation strategy is associated with the likelihood of issuing a management earnings forecast.

The next three hypotheses pertain to the properties of management earnings forecasts. With respect to forecast bias, early research (during the 1970–1980 period) documented a tendency for optimistically biased earnings forecasts (Basi et al. 1976; Penman 1980). However, this trend reversed over the time period 1994–2003 (which overlaps with our sample period) when more pessimistically biased forecasts were issued by managers. This recent trend is often explained as the result of managers applying their discretion in order to strategically walk-down market earnings expectations to avoid negative surprises at earnings announcements (Bergman and Roychowdhury 2008; Cotter et al. 2006; Matsumoto 2002).

Rogers and Stocken (2005) argue that the degree of which a manager biases forecasts for strategic purposes is affected by the difficulty that market participants experience detecting manager misrepresentation. The idea is that when there is little uncertainty about the firm’s earnings, it is less difficult for investors and competitors to assess the truthfulness of the manager’s forecast, which reduces managers’ willingness to strategically bias their forecasts. In contrast, when a firm’s earnings are volatile and unpredictable, it is more difficult for investors to evaluate the truthfulness of the manager’s forecast. In such cases, managers are less constrained in issuing self-serving forecasts. We conjecture that because exploratory innovation is inherently associated with higher earnings unpredictability, it is harder for investors to assess the truthfulness of management forecasts and to prove intentional bias on the part of managers, thereby leaving the management more room to bias earnings forecasts downwards to fulfill strategic needs.

Forecast bias is also affected by other strategic reasons such as the concern over competition. Disclosure of optimistic information encourages potential entrants to enter the product market, which imposes proprietary costs on the incumbent (Li 2010). Based on these arguments, we expect exploratory innovation strategy to be associated with greater pessimism in earnings forecast.

Hypothesis 2 (optimism)

Conditional on issuing a forecast, exploratory (exploitative) innovation strategy is negatively (positively) associated with the optimism of management earnings forecast.

Next we consider management forecast accuracy, which is defined as the forecast’s deviation from the actual earnings realization. Exploratory innovation involves experimenting with new technologies and approaches, and is inherently associated with higher likelihood of unanticipated failure that could lower earnings and consequently lead a firm to miss its own forecasts, thereby resulting in a larger forecast error. In contrast, the returns associated with exploitation innovation are more stable and predictable (He and Wong 2004). We therefore expect exploratory firms to be associated with lower earnings forecast accuracy.

Hypothesis 3 (accuracy)

Conditional on issuing a forecast, exploratory (exploitative) innovation strategy is negatively (positively) associated with management earnings forecast accuracy.

Lastly, we consider management forecast precision. Researchers suggest that forecast form captures the precision of managers’ beliefs about the future (King et al. 1990). More precise forecasts are generally perceived to reflect greater managerial certainty relative to less precise forecasts (Hughes and Pae 2004). Because returns associated with exploratory innovation are distant and uncertain, managers may provide a wider forecast range and thus less precise forecasts.

Prior studies show that proprietary costs are also negatively associated with forecast precision. Instead of disclosing private information precisely, firms may strategically choose to issue a vague forecast. For example, Verrecchia (2001) argues, “the manager may vaguely claim that the firm is expected to have earnings of at least $1 per share when in fact she expects earnings to be exactly $1 per share.” Li (2010) finds supporting evidence that competition among existing players in a given industry sector, a proxy for proprietary costs, is associated with less precise management earnings forecasts. Based on these discussions, we posit that exploratory innovation strategy is associated with less precise earnings forecasts.

Hypothesis 4 (precision)

Conditional on issuing a range forecast, exploratory (exploitative) innovation strategy is associated with less (more) precise management earnings forecast.

3 Sample selection and summary statistics

3.1 Sample selection

Our sample includes U.S. listed firms during the period of 1992–2012. Since we study innovation-intensive firms, we exclude firms that have never filed a patent with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) during our sample period. We collect firm-year patent information from Google USPTO Bulk Downloads.Footnote 4 This database provides rich information on all patents filed to and granted by the USPTO, including patent application and grant date, patent assignee name, the technology class of the patent, and detailed information on subsequent patents that cite the focal patent, etc.

Data on management forecasts is obtained from I/B/E/S Guidance. We obtain data on firms’ R&D investments and financial statement items from Compustat Industrial Annual Files, institutional holdings data from Thomson’s CDA/Spectrum database (form 13F), stock price data from CRSP. Data on analyst coverage and forecasting performance is also retrieved from I/B/E/S. After excluding observations with missing data, our final sample consists of 5959 firm-year observations.

3.2 Variable measurement

3.2.1 Measuring innovation strategy

We examine two types of innovation strategy, exploration and exploitation. Our measure of exploratory intensity Explore is calculated as the number of exploratory patents filed (and eventually obtained) in a given year divided by the number of all patents filed by the firm in the same year.Footnote 5 Similarly, our measure of exploitative intensity Exploit is calculated as the number of exploitative patents filed (and eventually obtained) in a given year divided by the number of all patents filed by the firm in the same year. These are commonly used measures of innovation strategy (see, e.g., Balsmeier et al. 2017; Custódio et al. 2015; Jia and Tian 2016). Following the management literature, we define patents unrelated to the firm’s existing knowledge and serving as pilot trials into new fields as “exploratory patents”, and patents built on a firm’s strength and expertise in the current domain as “exploitative patents” (e.g., Benner and Tushman 2002; Katila and Ahuja 2002; Phelps 2010). Operationally, we follow Custódio et al. (2015) and classify a patent as exploratory if at least 60% of its citations are based on new knowledge. We define a firm’s existing knowledge as its previous patent portfolio and the set of patents that has been cited by its own patents over the past five years. A higher value of Explore indicates a higher intensity of exploratory innovation. In contrast, a patent is classified as exploitative if at least 60% of its citations are based on current knowledge. A higher value of Exploit indicates a higher intensity of exploitative innovation.

3.2.2 Measuring management earnings forecasts

Our measure of the likelihood of issuing management forecast Issue, is a dummy variable that equals one if a firm issues at least one management earnings forecast during the year, and zero otherwise. Conditional on issuing a forecast, we also examine three properties of these forecasts. The first one is forecast Optimism, calculated as the difference between the forecasted earnings per share (EPS) minus the actual EPS, divided by the stock price 2 days prior to the management forecast release date. We multiple Optimism by 100 for better exposition of the regression coefficients.

The second forecast attribute that we examine is Accuracy, calculated as the absolute value of the difference between the management forecasted EPS and the actual EPS, divided by the stock price 2 days prior to the management forecast release date. As higher forecast error indicates lower accuracy, we multiple this construct by − 100 to transform it in an increasing-in-accuracy measure.

The third attribute that we examine is Precision, calculated as the difference between the upper and lower bound of the range forecast, divided by the stock price 2 days prior to the management forecast release date. Wider forecast range implies lower precision. So we multiple this construct by − 100 to transform it in an increasing-in-precision measure.

3.2.3 Measuring control variables

Following the disclosure literature, we control for a vector of firm and industry characteristics that may affect management forecast behavior. Prior literature has consistently shown evidence supporting a positive association between firm size and management earnings forecasts (e.g., Kasznik and Lev 1995). So we control for firm size, measured by the natural logarithm of total assets. Ajinkya et al. (2005) find that firms with greater institutional ownership are more likely to issue a forecast. Further, these forecasts tend to be more specific and accurate. Therefore we include institutional ownership, calculated as the arithmetic mean of the four quarterly institutional holdings reported through form 13F. We also include market-to-book ratio as a proxy for proprietary costs (Bamber and Cheon 1998). Ali et al. (2014) find that in more concentrated industries firms’ management earnings forecasts are less frequent, so we include industry concentration, measured by the Herfindahl index of 4-digit SIC industry where the firm belongs.

Prior research suggests that earnings are less value-relevant for loss firms (Hayn 1995), and that meeting or beating financial analyst expectation is less important for these firms (Degeorge et al. 1999). Matsumoto (2002) finds that firms with losses are less likely to guide analyst forecasts downward. In keeping with Matsumoto (2002) and Choi and Ziebart (2004), we include a dummy variable for firms that reported a loss in the previous period.

We also include leverage (measured by total debt to total assets ratio) as a proxy for risk, return-on-assets ratio as a proxy for profitability, asset tangibility (measured by net property, plants, and equipment scaled by total assets), stock return volatility over the prior year, and capital expenditure scaled by total assets. To control for the scope of innovation activities, we include number of patents, measured by natural logarithm of one plus firm’s total number of patents granted in a given year. Prior research has shown that analyst following influences the decision to forecast (e.g., Lang and Lundholm 1996), so we include the natural logarithm of one plus the number of analysts as an additional control variable. We provide detailed variable definitions in Appendix 1.

3.3 Sample description and summary statistics

Table 1 Panel A reports sample distribution by industry where industry classification is based on the 2-digit SIC code. The largest sector in our sample is Industrial Machinery & Equipment (SIC code 35), followed by Chemical & Allied Products (SIC code 28) and Electronic & Other Electric Equipment (SIC code 36), respectively. There does not appear to be significant clustering in the industry distribution. Panel B provides summary statistics of variables used in the baseline regressions. To minimize the effect of outliers, we winsorize all continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The mean forecast optimism is − 0.017, which is consistent with prior findings that managers tend to issue pessimistically biased forecasts in order to strategically walk-down market earnings expectations to avoid negative surprises at earnings announcements (Bergman and Roychowdhury 2008; Cotter et al. 2006; Matsumoto 2002). The mean forecast accuracy and precision, which have been multiplied by − 100 to transform into an increasing-in-accuracy/precision measure, is − 0.909 and − 0.366, respectively.

An average firm in our sample has an exploration intensity of 0.582, an exploitation intensity of 0.232, a natural logarithm of assets of 7.599, return on asset of 0.149, leverage ratio of 19.5%, scope of innovation activity of 3.100, PPE-to-assets ratio of 22.5%, capital expenditure ratio of 4.8%, institutional ownership of 0.713, industry concentration of 0.262, market-to-book ratio of 3.647, return volatility of 0.110, and natural logarithm of analyst coverage of 2.573.

Panel C of Table 1 displays the correlation among variables used in the baseline regression analyses. Because Explore and Exploit capture opposite innovation approach, they are significantly and negatively correlated. Explore has a significant positive relationship with the likelihood of issuing management forecasts, and a significant negative relationship with forecast optimism, accuracy and precision. In contrast, Exploit has a significant negative relationship with the likelihood of issuing management forecasts, and a significant positive relationship with forecast optimism, accuracy and precision. As univariate correlation analysis does not take into account the effects of the other correlated variables, we consider the evidence to be suggestive and rely on subsequent multivariate analyses to draw inferences.

4 Baseline empirical results

4.1 Baseline results

To assess how a firm’s choice of innovation strategy affects its management forecast behavior, we estimate the following models:

where i indexes firm, j indexes industry, and t indexes time. The dependent variables (either Issue or ForecastProperty) are the propensity of issuing management earnings forecasts and properties of these forecasts (Optimism, Accuracy, and Precision), respectively. The main variables of interest Explorei,t and Exploiti,t capture firm i’s exploratory and exploitative innovation intensity in year t.Footnote 6Control is a vector of firm characteristics that could affect management forecast propensity and characteristics as discussed in Sect. 3.2.3. Year and Industry capture year and industry fixed effects, respectively. We cluster standard errors at the firm level.

Table 2 presents the regression results of Eq. (1) that examines the impact of innovation strategy on the likelihood issuing management earnings forecasts. We apply the probit model given the binary nature of the dependent variable. We begin with a parsimonious model in column (1) that only includes the key variable of interest Explore as well as the industry and year fixed effects. The coefficient estimate on Explore is 0.182 and significant at the 5% level, suggesting that firms with higher exploration intensity are more willing to provide earnings forecasts in an attempt to mitigate severe information asymmetry problem. In column (2) we include additional control variables, and the coefficient estimate on Explore remains significantly positive. We also report the marginal effect on Explore on the bottom of Table 2 which is calculated as the change in the probability of issuing a forecast when Explore changes from the first to the third quartile and other variables are held at the corresponding means. The marginal effect is 0.048, suggesting that increasing exploration intensity from the first to the third quartile increases the probability of issuing management forecasts by 4.8%. Columns (3) and (4) report the results of exploitation intensity. In contrast to the results on exploration intensity, the coefficient estimate on Exploit is significantly negative in both columns. In the column (4), the marginal effect is 0.030, suggesting that increasing exploration intensity from the first to the third quartile decreases the probability of issuing management forecasts by 3.0%.

Results on the control variables are largely consistent with prior findings. Large firms, firms with higher institutional ownership and analyst coverage are more likely to issue management forecasts. In contrast, loss firms, firms with more tangible assets, and firms with higher return volatility are less likely to provide earnings guidance. Together, results from Table 2 provide evidence for hypothesis H1 and suggest that exploration (exploitation) intensity is associated with a higher (lower) likelihood of management forecast issuance.

Next we explore how innovation strategy affects properties of management earnings forecasts (i.e., hypothesis H2–H4), and the results are reported in Table 3. Because the decision to issue management forecast is non-random, therefore we use Heckman (1979)’s method to control for potential self-selection bias. In the first step, we predict the probability of issuing management forecast (as shown in Table 2) and obtain the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). We need to identify a variable that predicts forecast issuance, but is not a determinant of forecast optimism, accuracy and forecast precision (Larcker and Rusticus 2010). Prior research has shown that analyst following influences disclosure and the decision to forecast (e.g., Lang and Lundholm 1996), but is not associated with forecast accuracy (Ajinkya et al. 2005). Following Hribar and Yang (2016), we use analyst coverage (LnAnalysts) as the variable that is included in the forecast issuance model, but not included in the second stage models for forecast optimism, accuracy, and precision. IMR is then included as an additional control variable to explain the variation in management forecast properties.

In columns (1)–(3) of Table 3, the coefficient estimate on Explore is significantly negative, suggesting that earnings forecasts issued by firms with higher exploration intensity are less optimistic, less accurate and less precise. These results are consistent with the conjecture that managers of exploration-oriented firms may strategically walk-down market earnings expectations to avoid negative surprises and unwanted competition because such strategic bias is less likely be detected by the market due to higher information asymmetry. Moreover, these forecasts also exhibit higher error and lower precision due to the uncertainty of exploratory innovation success and the associated future earnings stream. Results on the control variables are largely consistent with prior studies. For instance, more profitable firms tend to issue more accurate and precise forecasts, while forecasts issued by loss firms and firms with higher return volatility are generally less accurate and precise.

We find opposite results in columns (4)–(6) where the main variable of interest is Exploit. That is, earnings forecasts issued by firms with higher exploitation intensity are more optimistic, more accurate and more precise. It is also worth noting that in columns (1)–(3) of Table 3, the IMRs are negatively loaded, suggesting that factors leading firms to pursue exploration strategy lead firms to issue less optimistic, accurate and precise management forecasts. In contrast, in Columns (4)–(6), the IMRs are positively loaded [although insignificant in column (6)], suggesting that factors leading firms to pursue exploitation strategy lead firms to issue more optimistic, accurate and precise management forecasts.

Taken together, results from Table 3 provide support for hypotheses H2, H3 and H4 that there is a negative (positive) relationship between exploration (exploitation) intensity and management forecast optimism, accuracy and precision.

5 Additional tests

5.1 Endogeneity: instrumental variable (IV) approach

A major concern of our baseline results is that omitted variables that affect both corporate innovation strategy and disclosure practices drive our results. Furthermore, there is a reverse causality concern that management disclosure practices may affect a firm’s choice of innovation strategy. For example, it is possible that firms with more frequent forecasts are under greater pressure to produce short-term performance and therefore choose an exploitative-oriented innovation strategy that generates faster and more stable return.

We attempt to address the endogeneity issue and infer causality in two ways. The first approach is the 2SLS analysis. We use instrumental variable (IV) that likely influences the firm’s innovation orientation but is unlikely to be directly related to management disclosure behavior. Our choice of instrumental variable, InventorMobility, is defined as the difference between the natural logarithm of one plus the inflow of inventors and the natural logarithm of one plus the outflow of inventors for a firm in a given year.

Since our focus is on innovation activities, we focus on the mobility of a firm’s R&D workforce (i.e., inventors). We collect individual inventor data from the Harvard Business School (HBS) patent and inventor database.Footnote 7 This database provides a unique identifier for each inventor so that we were able to track the mobility of individual inventors for a given firm. Following Marx et al. (2009), we identify mobile inventors as changing employers if he has ever filed two successive patent applications that are assigned to different firms. As we need at least two patents to detect a move, inventors that have filed a single patent throughout their career are excluded from our analysis. We assume that for a given firm, an inventor’s move-in year is the year when he filed his first patent at this firm. An inventor’s move-out year is when an inventor filed his first patent in a new firm. InventorMobility captures the net inflow of new inventors. Based on prior studies, we expect a positive (negative) relationship between InventorMobility and exploration (exploitation) intensity. We do not, however, expect InventorMobility to directly affect the propensity and attributes of management earnings forecasts.

Table 4 presents the regression estimates for the 2SLS analysis. In Panel A where the main variable of interest is exploration intensity, the coefficients on the instrument InventorMobility is significantly positive, which is consistent with our conjecture that inventor mobility is positively associated with exploratory innovation activities. The predicted value of InventorMobility from the first stage is then used in the second stage [i.e., columns (2)–(5)] to examine the relationship between exploration intensity and management forecast propensity and properties. The results are consistent with our baseline findings. Specifically, the coefficient on Explore remains significantly positive in column (2) where the dependent variable is the likelihood of issuing management forecasts. In contrast, the coefficient on Explore is significantly negative in columns (3)–(5), suggesting that earnings forecasts issued by exploratory-oriented firms are less optimistic, less accurate and less precise. Panel B of Table 4 reports the results where the main variable of interest is exploitation intensity. We find opposite results. Specifically, InventorMobility has a significantly negative relationship with Exploit. The coefficient on Exploit remains significantly negative in column (2) where the dependent variable is the likelihood of issuing management forecasts, and is significantly positive in columns (3)–(5), which suggests that earnings forecasts issued by exploitative-oriented firms are more optimistic, accurate and precise.

As an alternative way to address endogeneity and establish causality, we examine whether changes in a firm’s exploration and exploitation intensity are associated with corresponding changes in the propensity and properties of management earnings forecasts. Given the long-term nature of innovation activity, it is plausible that exploration and exploitation intensity exhibits certain stickiness, that is, exploration and exploitation intensity in the current year is correlated with the intensity in previous years. Therefore we calculate changes based on a 4-year window and the regression results are reported in Table 5.Footnote 8 To alleviate the simultaneity concern, we lag changes in exploration or exploitation intensity by 1 year. We find supportive evidence that an increase in exploration intensity is associated with a corresponding increase in forecast propensity and a decrease in the level of forecast optimism and accuracy. In contrast, an increase in exploitation intensity is associated with a corresponding decrease in forecast propensity and an increase in the level of forecast accuracy. Together, these findings provide additional support to our baseline findings and suggest that a causal relationship is at least partially in effect.

5.2 Disclosure of innovation-related information

In this section we offer one plausible explanation for the higher likelihood of earnings forecasts issued by exploratory firms. We posit that managers of exploratory firms may issue more earnings forecasts to satisfy the information needs of capital market participants in order to avoid disclosing proprietary information about their innovation activities (such as major milestone of R&D, details of pipeline projects or new products under development, turnover of key scientists and details of research teams). In a highly competitive environment, innovative firms would safeguard their projects from their established rivals and operate in a secretive manner to ensure profitability of the projects (e.g., Hall 2002). Proprietary information about their innovation activities (such as R&D expenditures or key project milestones) is more specific and valuable to competitors than innovation information contained in earnings forecasts (i.e., managerial forecasts of the contribution of undergoing innovation projects to firm value).

We examine whether firms with higher exploratory intensity (higher exploitative intensity) are associated with lower (higher) likelihood of disclosing proprietary information about their innovation activities. In particular, we examine the disclosure of R&D expenditures and non-financial, qualitative disclosure of innovation activities, respectively. R&D is a commonly used measure of innovation and technological progress in the firm (Lerner and Wulf 2007). It captures innovation input, including the wages of R&D staff and other related capital outlay. R&D disclosure decision is discretionary and the notion of what outlays are considered R&D can be difficult to assess (Horwitz and Kolodny 1980). Koh and Reeb (2015) show that a substantial portion of innovative firms (i.e., those who own patents) do not report R&D expenditures in their financial statements. They found that non-reporting R&D firms file more patents and more influential patents than firms that report zero R&D. Moreover, Pseudo-Blank R&D firms, relative to positive R&D firms, obtain individual patents with broader contributions, greater citation breadth, and lengthier competitor discovery periods despite having fewer patents. A plausible interpretation of blank R&D values, commonly accepted in the management literature, is that it represents a firm’s conscious decision to conceal positive R&D due to strategic reasons (e.g., McVay 2006).

Based upon this line of research, we test whether firms with higher (lower) intensity of exploratory (exploitative) innovation are less (more) likely to report R&D expenditures in their financial statements. Results from the 2SLS analysis are presented in Table 6. In the first stage our instrumental variable is still InventorMobility. The dependent variable R&D Disclosure is a dummy variable that equals one if a firm reports non-missing R&D expenditures in a given year, and zero otherwise.Footnote 9 In column (1), coefficient on the key variable of interest Explore is significantly negative. The marginal effect is 0.550, suggesting that increasing exploration intensity from the first to the third quartile decreases the probability of disclosing R&D expenditures by 5.5%. In contrast, in column (2), coefficient on Exploit is significantly positive. The marginal effect is 0.793, suggesting that increasing exploitation intensity from the first to the third quartile increases the probability of disclosing R&D expenditures by 7.93%.

Among control variables, larger firms, firms with more tangible assets and higher market-to-book value are more inclined to report R&D. Consistent with Koh and Reeb (2015), we also find that firms who own more patents are less likely to disclose R&D expenditure. Firms with higher return volatility are also less likely to disclose R&D information.

A growing body of research has emphasized the importance of value-relevant, non-financial information (e.g., Amir and Lev 1996; Barth et al. 1999). Knowledge-intensive firms can disclose additional, qualitative information about their innovation activities via media news. Compared to annual reports, news media allows companies to disseminate information in a more timely manner. We are interested in how corporate innovation strategy affects non-financial disclosure of innovation activities. To operationalize the inquiry, we search the LexisNexis News Wires for disclosure of innovation activities made by our sample firms. Following Gu and Li (2003), we classify the disclosure into three categories: (1) Type I: Information about progress of innovation (e.g., major milestone of R&D; details of pipeline projects or new products under development; details of research teams; implementation, continuation, or termination of R&D projects; financing for R&D projects; and whether R&D projects are on schedule); (2) Type II: Information about completion/commercialization of innovation (e.g., new product launch; licensing and royalty; transfer or sale of technology); and (3) Type III: Information about strategy of innovation (e.g., goal, objective, or plan of innovation; relation with current innovation, time frame; acquisition of other firms for new technology or other innovation capabilities). Table 7 Panel A presents the distribution of disclosure per firm-year by disclosure type. There appears to be more disclosure about progress of innovation, followed by completion/commercialization of innovation, and information about strategy of innovation, respectively.

In Panel B, we examine the impact of corporate innovation strategy on different types of innovation disclosure. We include the same set of control variables as in the baseline regressions but their coefficients are suppressed for brevity. Coefficient estimate on Explore is significantly negative in column (1) and (3) where the dependent variable is the probability of disclosure about the progress of innovation and the strategy of innovation, respectively. Interestingly, no significant relation is found between Explore and disclosure about completion/commercialization of innovation. Taken together, these results suggest that exploration-oriented firms are less willing to disclose detailed information about their innovation activities, especially regarding innovation that is still work-in-progress as well as regarding firm’s future innovation plans. But for completed and commercialized exploratory innovation, there is less need to keep it confidential, so exploratory firms do not strategically refrain from disclosing such information. Finally, in column (4) we consider a composite disclosure measure that equals 1 if a firm provides any one of the three types of disclosure in a given year. We again find a significantly negative coefficient on Explore, suggesting that overall, exploration-oriented firms tend to disclose less about their innovation activities in order to protect their proprietary know-how and to preserve competitive gains. We find largely opposite results when using exploitation as the independent variable. In particular, coefficient estimate on Exploit is significantly positive in column (1) and (4) where the dependent variable is the probability of disclosure about the progress of innovation and the composite disclosure measure, respectively.

Several prior studies (e.g., Guo and Zhou 2016; Gu and Wang 2005) find that capital market participants tend to incorporate patent information (i.e., a type of valuable non-financial information) in their investment decisions. However, different types of investors may exhibit differential ability in understanding the value of patents and their potential contribution to firm’s future economic performance. Specifically, we conjecture that between institutional investors and retail investors, the former are expert investors, so they possess superior abilities than retail investors in understanding the value of patents. As such, they are more likely to (successfully) demand the disclosure of such information. To test this idea, we consider the moderating role of institutional ownership on the relationship between innovation strategy and disclosure of innovation-related information.Footnote 10 As reported in Panel C of Table 7, we find largely supportive evidence that while exploration intensity is negatively associated with the disclosure of innovation information, such relationship is mitigated for firms with significant institutional ownership. In contrast, while exploitation intensity is positively associated with the disclosure of innovation information, such relationship is more pronounced for firms with significant institutional ownership.

5.3 Why do exploratory firms issue more conservative earnings forecasts?

Our main analysis shows that firms with higher exploration intensity tend to issue more “conservative” (i.e., pessimistically biased) management earnings forecasts than firms with higher exploitation intensity. In this section, we attempt to provide one plausible explanation. The management forecast literature suggests that managers prefer to avoid negative earnings surprises because such surprises generally lead to negative price revisions. Skinner and Sloan (2002) document that the absolute magnitude of the price response to negative surprises significantly exceeds the price response to positive surprises.

We conjecture that due to the highly uncertain nature and high failure rate of exploratory innovation, the probability that exploratory firms incur unsatisfactory earnings performance is high. Moreover, because investors face higher information gap with exploratory firms, they rely more heavily on management provided guidance in making investment decision. So if managers of exploratory firms issue overly-optimistic forecasts to hype up investors’ expectation and later miss their forecasts, they may lose credibility and investors may be disappointed more and respond with a greater decline in stock price, which is undesirable for the firm. So managers of exploratory firms may prefer more conservative forecasts to guide down investors’ expectation in order to avoid large disappointment and stock price decline.

To test this conjecture, we examine market reaction to management forecast error and the interaction effect with exploration and exploitation intensity, respectively. Specifically, we choose the last management earnings forecast prior to the annual earnings announcement and calculate management forecast error as (MgmtFoecastEPS-Actual EPS)/Price, where ActualEPS is the actual earnings per share (EPS) for the year. MgmtForecastEPS is the last management earnings forecast issued prior the earnings announcement date. Price is the stock price at the end of the day prior to the management forecast. Since we are interested in market reaction to disappointing news, we focus on a subsample of positive management forecast error, i.e., BadNews.

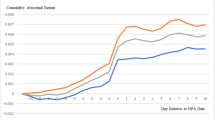

The results are reported in Table 8. The dependent variable CAR is cumulative abnormal returns in the (− 1, + 1) window around the actual earnings announcement. The daily abnormal return is calculated as the firm’s return on day t minus the daily return of a benchmark portfolio with the same size decile as the firm. We find that larger BadNews is associated with a greater stock price decline (as evidenced by a significantly positive coefficient on BadNews). Interestingly, coefficient on the interaction term BadNews × Exploration is significantly positive while the coefficient on the interaction term BadNews × Exploitation is significantly negative. These results provide support for our conjecture that investors react more negatively to the bad news of exploratory firms than to those of exploitative firms. This finding provides one potential explanation as to why managers of exploratory firms tend to issue more “conservative” earnings forecasts.

5.4 Innovation strategy and corporate information environment

Our findings so far suggest that exploratory-oriented firms are more willing to provide earnings forecasts, but they are reluctant to disclose information about their innovation activities. Given these two opposing disclosure practices, in this section we examine the net impact of innovation strategy on the firm’s overall information environment. Specifically, we examine the accuracy of analyst forecasts and the dispersion among them. Analyst dispersion reflects the complexity in understanding a firm’s ability to generate future cash flows (Datta et al. 2011; Chen and Huang 2013) and is often viewed as an indicator of information uncertainty, which potentially stems from either the uncertainty about a firm’s future performance or from a poor information environment (e.g., Barron and Stuerke 1998; Zhang 2006).

Prior studies show that financial analysts incorporate management earnings forecasts in their forecasts. Waymire (1986) finds that management forecasts are more accurate than contemporaneous analyst forecasts, and analyst earnings forecast accuracy improves after management forecasts are released. Cotter et al. (2006) show analysts react quickly to management guidance. Williams (1996) shows that analysts’ response to management forecasts depends on the usefulness of managers’ prior forecasts. Barth et al. (2001) find that analysts also use other value-relevant information as inputs in their forecasts.

Table 9 reports the second stage estimates of 2SLS regression analyses. The dependent variable in column (1) is analyst forecast error AnalystForecastError, defined as the 12-month average of the absolute values of analyst forecast error, calculated as actual earnings minus median forecast for the firm, deflated by stock price at the end of the previous fiscal year. We multiply forecast error by 100 for expositional purposes. We also control for a vector of firm characteristics that potential affect analyst forecast accuracy. As shown, the coefficient estimate on Explore is significantly positive, suggesting that exploratory firms overall suffer from more severe information asymmetry problem that results in higher analyst forecast error. In column (2) we examine analyst forecast dispersion AnalystForecastDispersion, which is defined as defined as the 12-month average of standard deviation of analyst forecasts for the firm, scaled by the stock price at the end of the previous fiscal year. We again multiply forecast dispersion by 100 for expositional purposes. The coefficient estimate on Explore is also significantly positive, suggesting that exploratory firms are associated with higher analyst forecast dispersion. We find opposite results in columns (3) and (4) where the main variable of interest is exploitation intensity.Footnote 11

5.5 Alternative measures of innovation intensity

In the main analyses, we measure a firm’s exploratory innovation intensity by the number of exploratory patents filed in a given year divided by the number of all patents filed by the firm in the same year. To ensure the robustness of our findings, we use two alternative measures of exploration intensity. The first one is SearchDistance, which is calculated as the technological search distance between a firm’s new patents and its patent portfolio. Following Chao et al. (2012) and Custódio et al. (2015), we take the current distribution of the number of a firm’s patents across two digit technological classes and then measure the degree of difference between this distribution and the analogous distribution calculated for new patents and adjusted for the expected degree of knowledge spillovers between patent classes (i.e., adjusted for the “closeness” of patent classes). A higher TechDistance indicates a higher degree of innovation complexity and novelty, and which is more exploratory in nature. We repeat the baseline analyses using TechDistance as the proxy for exploration intensity. Results (untabulated for brevity) are consistent with the baseline findings. In particular, TechDistance is positively associated with the propensity of issuing management earnings forecasts, but is negatively associated with forecast optimism, accuracy and precision.

The second alternative proxy is the similar to our main measures of exploratory and exploitative intensity but using 80% as the threshold (as opposed to 60%). Our findings remain robust.

6 Concluding remarks

In this paper, we examine the impact of a firm’s innovation strategy on its disclosure policy. Using a sample of innovation-intensive U.S. firms from 1992 to 2012, we find that firms with an exploration-oriented innovation strategy are more likely to provide management earnings forecasts. These forecasts are generally less optimistic, less accurate and precise. We find opposite results for exploitation-oriented innovation strategy.

To alleviate the endogeneity concern and to establish causality, we conduct the 2SLS analysis that uses the net inflow of R&D staff each year as an instrument. Results are consistent with the baseline findings. We also examine changes in the innovation intensity and how they are associated with corresponding changes in management earnings forecast behavior. We find that an increase in exploration (exploitation) intensity is associated with an increase (decrease) in the likelihood of issuing management earnings forecasts, but a corresponding decrease (increase) in the optimism, accuracy, and precision of these forecasts. These findings alleviate the endogeneity concern and provide support that our baseline results appear causal.

We also examine how corporate innovation strategy affects management disclosure practices related to innovation activities. We find that exploration-oriented firms are less willing to report R&D expenditures in their financial statements and are less inclined to provide additional non-financial information about their innovation activities, especially information regarding innovation that is still work-in-progress as well as regarding firm’s future innovation plans. However, such effect is mitigated when the firm has a large institutional ownership. We also find that market reacts more negatively to positive management forecast error (bad news) of exploratory firms, which provides a plausible explanation for why mangers of exploratory firms issue more conservative forecasts. Finally, we find that overall, exploration-oriented firms have a more opaque information environment than exploitation-oriented firms as manifested in higher analyst earnings forecast error and forecast dispersion.

Our study sheds new light on the determinants of corporate disclosure policy. Findings of this study suggest that knowledge-intensive firms appear to incorporate innovation strategy in developing their disclosure policy. Exploratory firms are more willing to provide forward-looking earnings estimates but tend to avoid disclosing detailed information about their innovation activities in order to guard their proprietary know-how and to preserve competitive gains. Findings of this paper also provide evidence on the disclosure consequences of corporate innovation strategy and enable knowledge-intensive firms to more fully understand the trade-offs they may face when attempting to develop competitive edge based on different types of innovation.

Notes

We take the view that public disclosure made by the firm to capital market investors is one venue through which competitors learn about the firm’s operation and R&D activities. This view is supported by prior studies (e.g., Li 2010) showing that competition from existing rivals decreases the quantity of firm’s disclosure to the capital markets, as proxied by management forecasts on earnings and capital expenditures.

Although exploration and exploitation are two distinct types of innovation strategy, prior studies also suggest that companies rarely make exclusive choice between them. March (1991) suggests that maintaining an appropriate balance between exploration and exploitation is critical for firm survival and prosperity. Therefore, instead of using an indicator variable to partition between exploratory and exploitative innovation strategy, we examine the intensity of exploration versus exploration.

The idea is that a firm’s workforce with long tenure and little mobility may hinder exploratory innovation. This is because stagnant workforce may fail to refresh itself in a timely manner, can no longer keep current with technological developments, and grow unable to offer new ideas into corporate activities (including R&D activities). Prior management literature notes that long tenure is often associated with rigidity and a commitment to established policies and practices that potentially kill the entrepreneurial spirit and hinder novel creation (Marcus and Goodman 1986; Tushman and O’Reilly 1997). March and March (1977) find that executives with short tenure contribute fresh insights and are more willing to take risks that deviate from industry norms. Jia (2017) study board tenure and find that firms with a higher portion of outside directors enjoying extended tenure have significantly lower exploratory innovation intensity. So we expect InventorMobility to be positively (negatively) related to exploitation (exploration) intensity, but is unlikely to directly affect management forecast behavior.

Available at http://www.google.com/googlebooks/uspto.html. There are a number of other studies that used this data source, including among others, Chien (2011), Weatherall and Webster (2014), Jia et al. (2016), and Tian and Ye (2017).

We use patent application year instead of patent grant year because prior studies (such as Griliches et al. 1987) have shown that the former is superior in capturing the actual time of innovation.

Available at http://dvn.iq.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/patent. See Lai et al. (2013) for details about this database.

As a robustness check, we also used a 3-year window and a 5-year window. Results remain qualitatively unchanged.

Some firms nay not report R&D expenses because they do not investment in R&D. To ensure our findings are not sensitive to this issue, we refined the R&D dataset by removing observations that have missing R&D in year t and do not have any patents in the next 3 years (year t + 1, t + 2, and t + 3). Although this approach may not perfectly identify firms that truly have no R&D in year t and therefore didn’t report it (appear as missing in Compustat), nevertheless this approach is one reasonable strategy to identify such firms. The underlying idea is that R&D investment made in a year is expected to generate some outcome in the next 3 years.

A number of prior studies have used institutional ownership to capture different types of investors. For example, Nofsinger and Sias (1999) use institutional ownership to partition shareholders into institutional and individual investors and examine herding and feedback trading of these two types of investors. Yan and Zhang (2009) use institutional ownership to examine the relation between institutions’ investment horizons and their informational roles in the stock market. Aghion et al. (2013) utilize institutional ownership to examine the role of institutional investors on corporate innovation performance.

Barron et al. (2002) suggest an alternative explanation to the results reported in Table 9. They hypothesize that analysts’ earnings forecasts for firms with a higher composition of intangibles contain higher proportions of private (or idiosyncratic) information relative to common information. Such effect reflects the disagreement arising from analysts placing greater reliance on their own idiosyncratic knowledge and skill relative to the common information they infer from sources such as current earnings. Their empirical results reveal that analyst consensus is negatively related to the degree to which a firm is comprised of intangibles, indicating that forecasts of earnings for high-intangible firms contain a higher proportion of private information. We find that exploratory firms’ earnings forecasts are less informative and such firms are less likely to disclose innovation-related information, so there is less “common information” available to and shared by analysts (Footnote 1 of Barron et al. 2002). As a result, we find a positive relationship between exploration intensity and analyst forecast dispersion (and error). This also reflects a poorer overall information environment for exploratory firms.

References

Adhikari BK, Agrawal A (2016) Religion, gambling attitudes and corporate innovation. J Corp Fin 37:229–248

Aghion P, Reenen JV, Zingales L (2013) Innovation and institutional ownership. Am Econ Rev 103:277–304

Ajinkya BB, Gift MJ (1984) Corporate managers’ earnings forecasts and symmetrical adjustments of market expectations. J Account Res 22:425–444

Ajinkya BB, Bhojraj S, Sengupta P (2005) The association between outside directors, institutional investors and the properties of management earnings forecasts. J Account Res 43:343–376

Ali A, Kalsa S, Yeung E (2014) Industry concentration and corporate disclosure policy. J Account Econ 58:240–264

Amason AC, Shrader RC, Tompson GH (2006) Newness and novelty: relating top management team composition to new venture performance. J Bus Venturing 21:125–148

Amir A, Lev B (1996) Value-relevance of nonfinancial information: the wireless communications industry. J Account Econ 22:3–30

Balsmeier B, Fleming L, Manso G (2017) Independent boards and innovation. J Financ Econ 123:536–557

Bamber L, Cheon YS (1998) Discretionary management earnings forecast disclosures: antecedents and outcomes associated with forecast venue and forecast specificity choices. J Account Res 36:167–190

Barron OE, Stuerke P (1998) Dispersion in analysts’ earnings forecasts as a measure of uncertainty. J Account Audit Financ 13:245–270

Barron OE, Byard D, Kile C, Riedl EJ (2002) High-technology intangibles and analysts’ forecasts. J Account Res 40:289–312

Barth ME, Clement MB, Foster G, Kasznik R (1999) Brand values and capital market valuation. Rev Account Stud 3:41–68

Barth ME, Kasznik R, McNichols MF (2001) Analyst coverage and intangible assets. J Account Res 39:1–34

Basi BA, Carey KJ, Twark RD (1976) A comparison of the accuracy of corporate and security analysts’ forecasts of earnings. Account Rev 51:244–254

Benner MJ, Tushman M (2002) Process management and technological innovation: a longitudinal study of the photography and paint industries. Admin Sci Q 47:676–706

Benner MJ, Tushman M (2003) Exploitation, exploration, and process management: the productivity dilemma revisited. Acad Manag Rev 28:238–256

Bergman N, Roychowdhury S (2008) Investor sentiment and corporate disclosure. J Account Res 46:1057–1083

Chao R, Lipson M, Loutskina E (2012) Financial distress and risky innovation. Working paper

Chen YC, Huang CY (2013) The moderating effect of industry concentration on the relations between external attributes and the properties of analyst earnings forecast. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Pol 16:1350019

Chen C, Chen Y, Hsu P, Podolski EJ (2016) Be nice to your innovators: employee treatment and corporate innovation performance. J Corp Financ 39:78–98

Cheng YT, Van de Ven A (1996) Learning the innovation journey: order out of chaos? Organ Sci 7:593–614

Chien CV (2011) Predicting patent litigation. Texas. Law Rev 90:283–287

Choi JH, Ziebart D (2004) Management earnings forecasts and the market’s reaction to predicted bias in the forecast. Asia Pac J Account Econ 11:167–192

Cohen WM, Levinthal DA (1994) Fortune favors the prepared firm. Manag Sci 40:227–251

Coller M, Yohn TL (1997) Management forecasts and information asymmetry: an examination of bid-ask spreads. J Account Res 35:181–191

Cotter J, Tuna I, Wysocki P (2006) Expectations management and beatable targets: how do analysts react to public earnings guidance? Contemp Account Res 23:593–624

Crossan MM, Lane HW, White RE (1999) An organizational learning framework: from intuition to institution. Acad Manage Rev 24:522–537

Custódio C, Ferreira MA, Matos P (2015) Do general managerial skills spur innovation? Working paper

Datta S, Iskandar-Datta M, Sharma V (2011) Product market pricing power, industry concentration and analysts’ earnings forecasts. J Bank Financ 35:1352–1366

Degeorge F, Patel J, Zeckhauser R (1999) Earnings management to exceed thresholds. J Bus 72:1–33

Diamond DW, Verrecchia RE (1991) Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of equity capital. J Financ 46:1325–1359

Frankel R, McNichols M, Wilson GP (1995) Discretionary disclosure and external financing. Account Rev 70:135–150

Gao L, Yang LL, Zhang JH (2006) Corporate patents, R&D success, and tax avoidance. Rev Quant Financ Account 47:1063–1096

Griliches Z, Pakes A, Hall B (1987) The value of patents as indicators of inventive activity. In: Dasgupta P, Stoneman P (eds) Economic policy and technical performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 97–124

Gu F, Li JQ (2003) Disclosure of innovation activities by high-technology firms. Asia Pac J Account Econ 10:143–172

Gu F, Wang WM (2005) Intangible assets, information complexity, and analysts’ earnings forecasts. J Bus Financ Account 32:1673–1702

Guo R, Zhou N (2016) Innovation capability and post-IPO performance. Rev Quant Financ Acc 2:335–357

Hall B (2002) The financing of research and development. Oxf Rev Econ Pol 18:35–51

Hayn C (1995) The information content of losses. J Account Econ 20:125–153

He Z, Wong P (2004) Exploration vs. exploitation: an empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organ Sci 15:481–494

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econom Soc 47:153–161

Henderson A (1999) Firm strategy and age dependence: a contingent view of the liabilities of newness, adolescence, and obsolescence. Admin Sci Q 44:281–314

Hirst D, Koonce L, Venkataraman S (2008) Management earnings forecasts: a review and framework. Account Horiz 22:315–338

Holmqvist M (2004) Experiential learning processes of exploration and exploitation within and between organizations: an empirical study of product development. Organ Sci 15:70–81

Horwitz BN, Kolodny R (1980) The economic effects of involuntary uniformity in the financial reporting of R&D expenditures. J Account Res 18:38–74

Hribar P, Yang H (2016) CEO overconfidence and management forecasting. Contemp Account Res 33:204–227

Hsu P, Lee H, Liu AZ, Zhang Z (2015) Corporate innovation, default risk, and bond pricing. J Corp Fin 35:329–344

Hughes J, Pae S (2004) Voluntary disclosure of precision information. J Account Econ 37:261–289

Jia N (2017) Corporate innovation strategy, analyst forecasting activities and the economic consequences. J Bus Financ Account 44(5–6):812–853

Jia N, Tian X (2016) Tell me how I am doing: the effect of timely feedback on patent activity. Working paper

Jia N, Tian X, Zhang W (2016) The real effects of tournament incentives: the case of firm innovation. Working paper

Jones DA (2007) Voluntary disclosure in R&D intensive industries. Contemp Account Res 24:489–522

Kaplan S, Tripsas M (2008) Thinking about technology: applying a cognitive lens to technological change. Res Policy 37:790–805

Kasznik R, Lev B (1995) To warn or not to warn: management disclosures in the face of an earnings surprise. Account Rev 70:113–134

Katila R, Ahuja G (2002) Something old, something new: a longitudinal study of search behavior and new product introduction. Acad Manag J 45:1183–1194

King R, Pownall G, Waymire G (1990) Expectations adjustments via timely management forecasts: review, synthesis, and suggestions for future research. J Account Lit 9:113–144

Koh PS, Reeb DM (2015) Missing R&D. J Account Econ 60:73–94

Lai R, D’amour A, Yu A, Sun Y, Fleming L (2013) Disambiguation and co-authorship networks of the U.S. patent inventor database (1975–2010). Working paper

Lambert R, Leuz C, Verrecchia RE (2007) Accounting information, disclosure, and the cost of capital. J Account Res 45:385–420

Lang M, Lundholm R (1996) Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. Account Rev 71:467–492

Larcker DF, Rusticus TO (2010) On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. J Account Econ 49:186–205

Lerner J, Wulf J (2007) Innovation and incentives: evidence from corporate R&D. Rev Econ Stat 89:634–644

Leuz C, Verrecchia RE (2000) The economic consequences of increased disclosure. J Account Res 38:91–124

Levinthal DA, March JG (1993) The myopia of learning. Strateg Manag J 14:95–112

Li X (2010) The impact of product market competition on the quality and quality of voluntary disclosures. Rev Account Stud 15:663–711

Manso G (2011) Motivating innovation. J Financ 66:1823–1860

March JG (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci 2:71–87

March JC, March JG (1977) Almost random careers—the Wisconsin school superintendency 1940–1972. Admin Sci Q 22:377–409

Marcus A, Goodman R (1986) Airline deregulation: factors affecting the choice of firm political strategy. Pol Stud J 15:231–246

Marx M, Strumsky D, Fleming L (2009) Mobility, skills, and the Michigan non-compete experiment. Manag Sci 55:875–889

Matsumoto D (2002) Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. Account Rev 77:483–514

McGrath RG (2001) Exploratory learning, innovative capacity, and managerial oversight. Acad Manag J 44:118–131