Abstract

We investigate gender disparities in the effect of COVID-19 on the labor market outcomes of skilled Ugandan workers. Leveraging a high-frequency panel dataset, we find that the lockdowns imposed in Uganda reduced employment by 69% for women and by 45% for men, generating a previously nonexistent gender gap of 20 p.p. Eighteen months after the onset of the pandemic, the gap persisted: while men quickly recovered their pre-pandemic career trajectories, 10% of the previously employed women remained jobless and another 35% remained occasionally employed. Additionally, the lockdowns shifted female workers from wage-employment to self-employment, relocated them into agriculture and other unskilled sectors misaligned with their skill sets, and widened the gender pay gap. Pre-pandemic sorting of women into economic sectors subject to the strongest restrictions and childcare responsibilities induced by schools’ prolonged closure only explain up to 65% of the employment gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

To curb the spread of COVID-19, governments implemented unprecedented measures to restrict economic activity and individual mobility. Early evidence shows that, all over the world, these restrictions disproportionately affected female workers, who lost their jobs at a greater rate than male ones, and female entrepreneurs, whose businesses saw a disproportionate decline in revenues and workforce.Footnote 1 While in the Global North these gendered effects have largely dissipated following the easing of the restrictions (Bluedorn et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2021), it is unclear whether the same holds true in the Global South, where low-capacity countries have mostly been unable to provide targeted support to workers and firms in economic distress and the labor market recovery is slowest (ILO, 2022b). As the integration of female talent in the labor force is a key determinant of GDP growth (Hsieh et al., 2019; Papageorgiou et al., 2018), evaluating how skilled female workers and entrepreneurs in low-income economies have been affected by COVID-19 is crucial for understanding how productivity will fare in these regions once the pandemic subsides.

To make progress on this question, we investigate gender disparities in the effects of two nationwide lockdowns implemented in Uganda on the labor market outcomes of a sample of 714 young, urban, and highly skilled workers and entrepreneurs who, pre-pandemic, received post-secondary vocational education and were employed in a wide range of manufacturing and services sectors. These workers, representing the top 3% of the country’s education distribution and characterized by no gender differences in pre-pandemic employment rate and job security, should not be considered as representative of the Ugandan youth, but rather the expression of the emerging urban working class driving the country’s structural transformation.

Relying on a unique high-frequency panel dataset spanning from January 2020 to September 2021, we track these workers’ labor market outcomes before, during, and after the lockdowns, evaluate gender differences in the early responses to the lockdowns and in recovery patterns, and investigate the root causes of the observed trends.

We find that the first lockdown reduced the employment rate by 53 p.p. (69% over the baseline level) among female workers and by 35 p.p. (45%) among male workers, generating an employment gender gap of 20 p.p. Once the restrictions were lifted, male employment rate was back to its pre-pandemic level in six months. Conversely, as 10% of the previously employed women remained jobless and 35% became occasionally employed, female employment rate remained below its pre-pandemic projection. The employment gender gap, further amplified by the second lockdown that once again disproportionately reduced female employment, persisted eighteen months after the onset of the pandemic. We identify three additional gendered responses. First, the disproportionate job losses experienced by female wage-employees resulted in a more pronounced shift towards self-employment. Second, the lockdowns displaced women from the sectors in which they received vocational training and relocated them into agriculture and other unskilled sectors. Third, the earnings gender gap widened. The transition of female workers towards sectors in which they cannot leverage their comparative advantage and experience is likely to induce a disproportionate depreciation of their productive skills. This is especially worrisome when considering the monetary and time investment in vocational education made by these workers.

We investigate two possible determinants of these dynamics identified by the literature: female workers’ concentration in economic sectors deemed as non-essential and with higher risk of infection (Alon et al., 2020; Couch, 2020) and the extraordinary childcare responsibilities generated by schools’ closures (Alon et al., 2022; Andrew et al., 2022; Couch, 2020; Del Boca et al., 2020; Farré et al., 2022; Hupkau & Petrongolo, 2020; Oreffice & Quintana-Domeque, 2021; Sevilla & Smith, 2020; Zamarro & Prados 2021). Pre-pandemic, our female respondents were over-represented in sectors subject to the strongest restrictions. Initial closures in these sectors explain 50% of the employment gender gap during the first lockdown; their contribution gradually declines after the restrictions are lifted, but once again rises to 13% during the second lockdown. Moreover, in periods of schools’ closure employment declines with the number of school-age children in the household for women but not for men. Childcare responsibilities contribute between 11% and 24% of the employment gender gap in the later stage of the pandemic, following the prolonged school closure. We estimate that, together, gender differences in employment sectors and childcare responsibilities explain up to 65% of the employment gender gap. Consistent with evidence from high- and low- income countries, a considerable share of the gap remains unexplained (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020; Furman et al., 2021; Kugler et al., 2023; Montenovo et al., 2022).

The gender gap in job losses of 20 p.p. we observe is considerably larger than the 2.5–9 p.p. gap documented in other high- and low- income countries for more representative populations (Alon et al., 2022; Casale & Shepherd, 2022; Kugler et al., 2023; Stantcheva, 2022). We identify three drivers of such large and persistent effect. First, our young respondents were hit by the pandemic in the earliest, most vulnerable stage of their careers. Several studies consistently find larger job losses (Kikuchi et al., 2021; Kugler et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2022; Montenovo et al., 2022) and gender differentials (Kristal & Yaish, 2020) among the youth. Second, our respondents were largely employed outside the relatively more sheltered agricultural sector and, given the hands-on nature of their jobs, they were mostly unable to work from home. Third, our respondents could not rely on publicly financed retention schemes, which supported about 50 million jobs across OECD countries (OECD, 2020).

We contribute to the literature on the gendered effects of COVID-19 in three ways. First, with a unique dataset we assembled, we provide an otherwise unavailable look at how the pandemic affected the emerging class of skilled urban workers in a low income-country, for which we find large and persistent gendered effects. This finding expands our understanding of the effects of COVID-19 in the Global South. Evidence from Nigeria shows that gender gaps quickly dissipated in settings characterized by the prevalence of agricultural or other non-farm subsistence activities (Alon et al., 2022). Our results suggest the existence of heterogeneous recovery patterns for different segments of the labor market: even in highly agricultural countries, women employed in manufacturing and services, strongly resembling the workforce of more advanced economies, may never fully recover without targeted support. Consistent with our hypothesis, recent studies report partial recovery and enduring gender gaps in labor market outcomes for the subpopulations of female wage employees across ten low-income countries (Kugler et al., 2023), for female workers in South Africa– a more economically diversified middle-income country (Casale & Shepherd, 2022), and for female return migrants previously employed in urban settings in India (Allard et al., 2022). Overall corroborating our view and concerns, the latest estimates from the Global South confirm that female employment is recovering at a slower pace than male employment, contributing to a growing employment gender gap globally (ILO, 2022a). Second, we provide new insights on how the effects of the pandemic compare between the Global North, where highly educated women were the least affected (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020; Foucault & Galasso, 2020; Lee et al., 2021), and the Global South, where women from some highly educated groups experienced large and persistent effects. Third, while most studies use single or repeated cross-sections and short panels, we leverage one of the longest panel datasets spanning the COVID-19 pandemic. The panel structure of our data, the extended time span it covers, and the availability of pre-pandemic information allow us to monitor labor market trajectories in and out of employment and across sectors, test the persistence of the initial shock for eighteen months, and isolate the specific effects of COVID-19 containment measures from pre-trends.

The findings of this paper indicate that the labor market trajectories of economically empowered women in low-income countries are highly vulnerable to temporary economic shocks. If not pressingly tackled, the labor market disconnection and sectorial misallocation of skilled female workers induced by the COVID-19 pandemic may result in additional barriers to economic growth. Governments, international organizations, and NGOs should prioritize supporting enterprises in female-dominated sectors and women seeking stable employment. Closing the employment gender gap will additionally require identifying the forces behind its unexplained portion, such as employer discrimination or social norms.

2 Context

Uganda has 78% of the population aged below 30 (International Youth Foundation, 2011) and a youth underutilization rate of 68% (ILO, 2017). To address the prevailing skills mismatches and workers’ underqualification, in 2012 the Ugandan government implemented a decennial strategic plan aimed at reinforcing its vocational education system (EPRC, 2021), which proved effective at generating productive human capital (Alfonsi et al., 2020). Currently representing 4% of the youths, post-secondary vocational graduates have above mean employment rates and earnings.Footnote 2 This highly skilled group was projected to grow as further educational and labor market opportunities emerged with the country’s sustained economic growth (EPRC, 2021).

The positive economic outlook was, however, undermined by the COVID-19 shock, which contracted the economy to its slowest pace in three decades (World Bank, 2021). To curb the spread of the virus, the government implemented one of Africa’s strictest sets of nationwide containment measures. It closed schools on March 20, 2020, and non-essential businesses during a first national lockdown implemented between March 30 and May 26, 2020. The government also imposed travel bans for vehicles and a dusk-to-dawn curfew. While most restrictions for economic activity were lifted in June 2020, schools remained closed until February 2021 when, except for pre-primary schools, they gradually reopened.Footnote 3 Amid the fear of a second wave of cases, the government imposed a second, milder, lockdown between June 19 and July 31, 2021. Although most businesses were not shut down, travel limits, a stringent curfew, the suspension of public transportation, and the new school closure lasting until January 2022 hindered once again the fragile economic recovery.

3 Data and sample

3.1 The panel dataset

The sample we assembled consists of 714 young and skilled workers who graduated between 2014 and 2019 from five vocational training institutes (VTIs) located in the Central and Eastern regions of Uganda.Footnote 4,Footnote 5 Given the high technology access and educational attainment of our population, we conducted all surveys by phone. This initial choice allowed us to avoid disruptions in our data collection process once COVID-19 hit and phone interviews became the only tool to collect time-sensitive information. As Fig. 1 shows, we interviewed our respondents in January, July and December 2020 and in September 2021. In each survey round, we collected detailed current and retrospective information, and obtained five additional data points for each respondent: the time of the first activity after graduation, different for each respondent potentially coinciding with January 2020, March and May 2020, and May and July 2021.Footnote 6 Measuring labor market outcomes before, during, and after the two lockdowns allows us to evaluate both early responses to the lockdowns and the persistence of the effects eighteen months from the onset of the crisis.

3.2 The study population

Our respondents graduated from the National Certificate, a post-secondary education vocational program providing trainees with a nationally accredited skills certificate. They received training in electrical wiring (23%), motor mechanics (19%), food and hospitality (15%), plumbing (12%), tailoring (8%), secretarial and accounting studies (7%), construction (5%), early childhood development (5%), hairdressing (3%), agriculture, welding, carpentry, and machining and fitting (1% or less).

Table 1 reports the respondents’ baseline characteristics: they are on average 25 years old, they come from all over the country, 36% are married, and 47% have children. Pre-pandemic, 56% of them were paid employees, 21% owned a business, 13% were without an occupation,Footnote 7 and a few were enrolled in educational programs or engaged in causal occupations.

Women represent 41% of the sample. Despite being on average 1.5 years younger than men, they are as likely to be married, and live with more school-age children. Crucially, pre-pandemic female workers are as likely as male ones to be employed and hold quality jobs, as indicated by the absence of gender differences in labor market experience, the employment rates in skilled sectors and in the training sector, the self-employment rate, and the probability to work in, or own, a registered firm. Women are also more likely to have a permanent job and less likely to be engaged in casual occupations. These statistics suggest that our female respondents are among the most economically empowered women in Uganda.

3.3 Representativeness

The uniqueness of our sample clearly emerges when comparing it to the population of young Ugandan adults in the Uganda National Household Survey from 2016/2017 (UNHS). With 15+ completed years of education, our workers belong to the top 3% of the education distribution for Ugandan youths (Fig. 10). Their employment rate in non-agricultural occupations and earnings are 27 p.p. (56%) and $33 (46%) higher than average respectively (Table 2). In stark contrast with the average Ugandan youth, largely employed in agriculture or unskilled occupations, 85% of the employed respondents were working in skilled, non-agricultural jobs (Table 3).

When comparing our sample to post-secondary VTI graduates from the UNHS, we find smaller differences in socio-economic and labor market characteristics (Table 2) and a high sectorial overlap (Table 3). Although all differences shrink, they remain significant. This positive selection is plausibly driven by the quality of the VTIs from which our workers graduated (which were pre-selected by BRAC Uganda, our implementing partner, based on their reputation, infrastructure, equipment, and teachers’ educational attainment) and by the fact that most of our graduates reside in the country’s richest urban areas. Accordingly, our findings extend to other top-notch, young and skilled workers in urban Sub-Saharan Africa.

3.4 Attrition

We successfully interviewed 714 workers in January 2020, 615 in July 2020 (attrition rate: 14%), 561 in December 2020 (21%) and 561 in September 2021 (21%).Footnote 8 Table 4 investigates the existence of differential attrition by gender. While we find no evidence of differential probability to reach female and male respondents in the first three survey rounds, female respondents are 6.2 p.p. less likely to be interviewed in the last one. We further investigate this issue by classifying female and male respondents into Never and Ever Attritors, depending on whether we were able or not to interview them in all the four survey rounds, and comparing their baseline characteristics in Table 5. Reassuringly, female Ever and Never Attritors do not significantly differ by any key baseline characteristics, suggesting that our findings are not driven by compositional changes in the female sample correlated with the COVID-19 shock. Male Ever Attritors do not differ from male Never Attritors on wage and self- employment rates nor earnings. However, male Ever Attritors are less likely to be employed in skilled and training sectors (suggesting they are negatively selected, and our estimated gender gaps are an upper bound), but are also more likely to be employed in a permanent job (pushing in the opposite direction). Combined, these findings suggest that male Ever and Never Attritors are not systematically different. Table 8, comparing Ever and Never Attritors after pooling men and women, introduces no new determinants of attrition. In Section Robustness Tests we show that our results remain robust in the balanced panel of Never Attritors, and in 63–100% (depending on the outcome) of the scenarios about attritors’ employment we build around the possibility that Ever Attritors are either positively or negatively selected; the results only disappear under implausible assumptions.

4 Results

4.1 Empirical strategy

We provide evidence of the emergence and persistence of new gender gaps in the labor market by plotting average employment rate, employment rate in the training sector, employment rate in skilled sectors, and monthly earnings over time for men and women. Formally, we test for the existence of gender gaps by estimating the following Equation:

Yi,t is the outcome measured for respondent i at time t; αi and αt are individual and time fixed effects. Femalei is an indicator for female respondents, and ϵi,t the error term. Standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity and clustered at the individual level. The βy coefficients measure the evolution over time of the gender gap in the outcome variable. They provide a formal test for the absence of gender disparities in the labor market pre-pandemic and for their emergence and persistence during the pandemic. Identification is provided by comparing the outcome between men and women relative to March 2020, our latest pre-pandemic data point, after controlling for time-constant individual characteristics (including those that are unbalanced in Table 1) and common shocks across individuals.

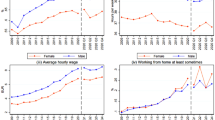

4.2 The Ugandan shecession

Figure 2 illustrates the differential impacts of the two lockdowns on male and female employment rates over the course of 2020 and 2021. Prior to the onset of the pandemic, female and male employment levels were nearly identical and constant at around 77%. Consistent with a high fear of infection and the severe restrictions imposed on economic activity, during the first lockdown in May 2020, the employment rate fell by 53 p.p. (69%) for females and 35 p.p. (45%) for males, generating an employment gender gap of 20 p.p. Once the restrictions were lifted, male employment recovered faster than female employment, and by December 2020 it was back to its pre-pandemic level. At that time, female employment was still 8 p.p. (10%) lower than its baseline level. The employment gender gap endured until May 2021, widened to 24 p.p. during the second nationwide lockdown in July 2021, when female workers once again experienced a relatively larger drop in employment, and persisted through September 2021, despite employment levels beginning to recover following the easing of restrictions.

The Emergence and Persistence of a Gender Gap in Employment After the Lockdowns. The figure illustrates the average share of respondents that are employed over time and by gender. At each point in time, a respondent is coded as employed if her main activity is either wage- or self-employment. The first data point refers to the respondents’ first activity after completing vocational education. It may coincide with the activity in January 2020 and its start and end date may be different for each respondent. It can be interpreted as the share of individuals who ever worked after completing vocational education. 95% robust confidence intervals are reported

Panels (a) and (b) of Fig. 3 decompose the effect on overall employment rate into the effects on wage- and self-employment rates respectively. It emerges that the drop in wage-employment is the main driver of the overall effect. One plausible reason is the higher level of compliance to government rules among larger and established firms employing wage labor. Moreover, some wage-employed workers gradually responded to the layoffs by setting up their own activity. This seems especially true among women, who suffered the largest drop in wage-employment. Following job losses, most respondents remained without an occupation, as they did not resume education (panel [c]) nor engaged in casual occupations to make ends meet (panel [d]).

The Emergence and Persistence of Gender Disparities in Occupation Type After the Lockdowns. The figure illustrates the average share of respondents that are wage employed (panel a), self-employed (panel b), enrolled in educational programs (panel c), and engaged in casual occupations (panel d) over time and by gender. The first data point refers to the respondents’ first activity after completing vocational education. It may coincide with the activity in January 2020 and its start and end date may be different for each respondent. 95% robust confidence intervals are reported

Following the easing of the restrictions, the rebound in employment was driven both by previously employed workers who had lost their jobs re-entering the labor market (panel [a] of Fig. 4) and by initially non-employed workers progressively finding a job, the first following graduation for 50% of them (panel [b]). While the gradual employment of new cohorts of graduates and of other non-employed was symmetrical by gender,Footnote 9 the re-entry of previously employed women remained between 10 and 35 p.p. lower than that of previously employed men throughout the pandemic. Panel (c) reveals that 80% of the men employed pre-pandemic were still employed in two-thirds of the post-lockdown data points, with a 40% employed throughout the post-lockdown period. Conversely, 10% of the previously employed women remained jobless, and another 35% were employed in half or less of the pandemic periods. The differential re-entry patterns of initially employed workers by gender explain the persistence of the employment gender gap for eighteen months.

The Drivers of the Recovery in Employment After the Lockdowns. Panels (a) and (b) illustrate the average employment rate over time and by gender for the 532 respondents who were employed in January 2020 and the 159 respondents who were not employed in January 2020. Employed respondents were either wage- or self-employed. Non-employed respondents were either enrolled in educational programs, or engaged in casual occupations, or without an occupation. The first data point refers to the respondents’ first activity after completing vocational education. It may coincide with the activity in January 2020 and its start and end date may be different for each respondent. 95% robust confidence intervals are reported. Panel (c) illustrates the share of female and male respondents employed in zero to six periods between May, July, and December 2020, and May, July, and September 2021. The sample is restricted to Never Attritors who were employed pre-pandemic (January and March 2020)

Additionally, we find that the lockdowns had gendered effects on the employment rate in the training sector, the employment rate in skilled sectors, and earnings. Panel (a) of Fig. 5 shows that the share of respondents employed in their training sectors, approximately 58% for both genders pre-pandemic, dropped by 25 p.p. (43%) for males and by 45 p.p. (77%) for females during the first lockdown in May 2020. While men were back on their pre-pandemic trajectory by December 2020, female employment rate in the training sector remained 20 p.p. below its baseline level for eighteen months. Panel (b) shows that, conditional on employment, the share of men employed in their training sectors remained constant throughout the pandemic. Conversely, the share of women employed in their training sectors conditional on employment, equal to that of men pre-pandemic, fell by 22 p.p. (29%) during the first lockdown and never recovered. Panel (c) shows that the share of respondents employed in skilled sectors, equal to 67% for both genders pre-pandemic, dropped by 32 p.p. (48%) for men and by 53 p.p. (79%) for women during the first lockdown, generating a previously non-existent gender gap in skilled employment which persisted for eighteen months after the onset of the pandemic. Panel (d) clarifies that the initial drop in male skilled employment is entirely driven by the drop in employment, as the share of men employed in skilled sectors conditional of employment remained constant over time. Conversely, the share of female respondents employed in skilled sectors conditional on employment, equal to that of men pre-pandemic, dropped by 33 p.p. (38%) during the first lockdown and never rebounded in the following eighteen months. Figure 12 illustrates that the reduction in skilled employment was driven by female workers pivoting towards agriculture (although this effect slowly dissipates) and non-agricultural unskilled occupations, where female employment increased by 2 p.p. and 15 p.p. (200%) respectively. Female employment in agriculture and in other unskilled sectors grew disproportionately following the second lockdown as well. Lastly, panel (e) of Fig. 5 shows that the initial earnings gender gap widened during the pandemic. During the first lockdown in May 2020, earnings fell in a similar fashion for female and male workers. By December 2020, the gender pay gap had tripled, reaching $69 from a baseline of $23, and stabilized afterwards. Panel (f), showing the evolution by gender of earnings conditional on employment, reveals that the men who remained employed saw their earnings decline by $35 (30%) on average during the first lockdown. Conversely, female average conditional earnings remained constant, plausibly due to the positive selection of the few women who were still employed in May 2020. However, the number of employed women in May 2020 is so small that the standard errors are too large to make any claims on female earnings and the earning gender gap in this period. By December 2020, the gender pay gap in earnings conditional on employment had widened from $38 to $78 (+105%). This widening is driven by both higher male and lower female conditional earnings. The former may result from career advancements: for vocational graduates in the UNHS sample each additional year of age is associated to a $7 increase in monthly earnings (panel [b] of Fig. 11); the $25 increase we document may be driven by the sample positive selection. Panel (b) of Fig. 11 suggests that female earnings should have grown too in absence of the pandemic. The observed stagnation may originate from the prolonged inactivity during the lockdown or from the shift to unskilled sectors and into self-employment, but we are not powered enough to draw definitive conclusions.

The Emergence and Persistence of Gender Disparities in Employment Quality After the Lockdowns. The figure illustrates the average employment rate in the training sector (upper panels) employment rate in skilled sectors (middle panels) and monthly earnings (lower panels) over time and by gender. See the notes to Table 1 for details on how the variables are constructed. In panels (a, c, e), the outcome is set to zero for non-employed respondents, and the average outcome in each point of time is calculated over all respondents found in the corresponding survey round. In panels (b, d, f), the outcome is missing for non-employed respondents, and the average outcome in each point of time is calculated over employed respondents only. The first data point refers to the respondents’ first job after completing vocational education. It may coincide with the job in January 2020 and its start and end date may be different for each respondent. Earnings data were not collected in March and July 2020. In January 2020 and May 2020 respondents placed their earnings in a 15 USD bracket. We use the range midpoint. From December 2020 onwards earnings were asked as a continuous variable. For self-employed workers, the variable measures monthly profits, collected following the same procedure. Results look very similar when we use the range midpoint throughout. 95% robust confidence intervals are reported

Table 6 reports the βy coefficients from Eq. (1), c of the gender gap for each of our main outcomes. Column (1) confirms that, pre-pandemic, there was no employment gender gap. A 16.6 p.p. gender gap emerged with the first lockdown in May 2020, and grew to 25.5 p.p. in July 2020 despite the easing of the restrictions. By December 2020, the gap had reduced to 8.5 p.p., but it widened again during the second lockdown in July 2021, when it reached 19.4 p.p. Column (2) shows that wage employment contributes 11.8 p.p. (71%) of the new employment gender gap in May 2020 and the total of the gap afterwards. Column (3) shows that self-employment contributes the remaining 4.7 p.p. (29%) of the employment gender gap in May 2020. However, by July 2020 the gender gap in self-employment had disappeared, and later it switched sign as more and more women set up their businesses following job losses or initial non-employment. In September 2021, women were 9.7 p.p. more likely to be self-employed than men. Columns (4) and (5) show the evolution of the gender gap in the employment rate in the training sector, unconditionally and conditional on employment respectively. The former ranges between 13 and 24 p.p. during the pandemic; the latter between 3.6 (insignificant) and 13 p.p. Columns (6) and (7) show the evolution of the gender gap in employment rate in skilled sectors. Unconditionally, the gap in skilled employment ranges between 11 and 24 p.p. during the pandemic; conditional on employment, the gap ranges between 1.7 (insignificant) and 12 p.p. Columns (8) and (9) report the estimates of the earnings gender gap over time, unconditionally and conditional on employment respectively. Consistent with the graphical evidence, we observe a widening of the gap only in December 2020. The gap in unconditional earnings ranges between $38 and $50; conditional on employment, the gap ranges between $33 and $49. These findings confirm that the two lockdowns implemented in Uganda had long-lasting gendered consequences on the employment, employment type, sectorial distribution, and earnings of these economically empowered women.

Last, we investigate with t-tests by gender whether the lockdowns had gendered effects on working hours, the need to borrow and to sell assets as a coping strategy, and mental health, and we present suggestive evidence of these effects in Table 9. Panel (a) shows that, conditional on employment, female wage employees were 24.6 p.p. more likely than male ones to report they reduced working hours in May 2020. In July 2020, women were still 11.3 p.p. more likely than men to report their pre-pandemic businesses were working with reduced hours of operation. Although differences in working hours had dissipated by December 2020, they seemingly reemerged around the second lockdown in July and September 2021, when employed women reported working 0.4 marginally insignificant fewer hours per day than employed men. In panel (b) we investigate our respondents’ need to borrow money during the pandemic. We find no gender differences in borrowing initially, but self-employed women were 9.8 p.p. more likely than their male counterparts to borrow money to cope with the second lockdown. Panel (c) shows that men and women were equally likely to sell assets, and panel (d) finds that women were persistently more likely than men to report being anxious because of the pandemic: fear of infection and fear of losing employment were the main sources of their worsened mental health. This result is in line with Bau et al. (2022), who show that COVID-19 containment measures substantially reduced female well-being in India.

In sum, tracking the labor market outcomes of a sample of young and skilled Ugandan workers during the COVID-19 pandemic reveals, first, that women suffered from disproportionate job losses. Almost half of the previously employed women failed to stably re-enter employment, driving the persistence of a previously inexistent employment gender gap of 20 p.p. for eighteen months. Second, we find that the disproportionate job losses experienced by female wage-employees resulted in a more pronounced shift towards self-employment. Third, we document a disproportionate displacement of female workers from their training sector towards agriculture and other unskilled sectors in which they can no longer leverage their comparative advantage. Fourth, we observe a widening of the gender pay gap. The sharp and simultaneous decline in female employment during both lockdowns, paired with the strong attachment to the labor market signaled by our female respondents through VTI enrollment, suggest we would almost certainly have not observed these dynamics in the absence of the pandemic. The sectorial misallocation we document may bring to a disproportionate depreciation of women’s productive skills accumulated during vocational education. And the endurance of these new gender disparities in the labor market for eighteen months since the onset of the pandemic suggest they will all persist beyond the end of our study period.

4.3 Robustness tests

We test the stability of our findings in several ways. Figures 13, 14, and Table 10 illustrate the emergence and persistence of gender gaps in the main outcomes in the balanced panel of respondents. Together with the overall similarity of Ever and Never Attritors at baseline documented in Table 5, this evidence indicates that the observed gaps in labor market outcomes are not driven by compositional changes in the sample over time, but rather reflect true labor market dynamics for our workers. Table 11 reports several bounds to our estimated employment gender gap to investigate its sensitivity to different assumptions about the employment status of attritors, following Horowitz and Manski (2006) and Kling et al. (2007). A considerable gender gap in employment emerges even in the unlikely, lower bound scenario in which all the female attritors and none of the male attritors are employed, although it becomes smaller and insignificant over time. We then test the sensitivity of the gender gaps in employment in the training sector and in skilled sectors under a range of assumptions about attritors’ employment and sector. Gender gaps emerge in 88% and 63% of the scenarios respectively. The four cases in which the gaps disappear are the most pessimistic scenarios for men and the least pessimistic for women. In these scenarios, all male and female attritors are, respectively, unemployed and employed in the training sector; employed outside the training sector and employed in the training sector or unemployed; employed in an unskilled sector and employed in a skilled sector. The robustness of our findings in most scenarios and the overall similarity between attritors and non-attritors at baseline make us confident that these four cases are the least likely among those considered, and that none of our result is driven by attrition. Then, Fig. 15 shows similar employment patterns for different cohorts of women, indicating that fertility choices happening at fixed distance from graduation do not confound our results. Figure 16 shows that the two lockdowns have similar effects on respondents differing by baseline characteristics other than gender, highlighting the gendered nature of these dynamics and pointing towards a broader generalizability of our findings. Last, Fig. 17 shows that our findings are not driven by sector-specific shocks, as employment patters remain similar after removing from the sample respondents from one training sector at a time.

4.4 Where is the new and persistent employment gap coming from?

4.4.1 The role of employment sectors

During the first lockdown, the government suspended economic activity in sectors either deemed non-essential or involving close interactions with clients. We test the hypothesis that the pre-pandemic sorting of women in these sectors contributed to the emergence and persistence of the observed employment gender gap.

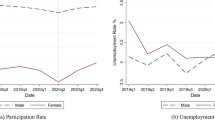

In panel (a) of Fig. 6 we plot the sectors in which our workers were employed pre-pandemic along two dimensions: the share of female workers in each sector and the share of employed workers whose business were closed during the first lockdown in May 2020. The figure shows that economic sectors are highly segregated by gender: sectors such as tailoring, teaching, hairdressing and secretary employ almost only female workers; sectors like motor-mechanics, plumbing, electrical work and construction remain traditionally male-concentrated sectors. The same level of segregation occurs in the Ugandan labor market overall (columns 2 and 3, Table 3). Consistent with women’s pre-pandemic sorting in sectors subject to the strongest restrictions, we observe a strong positive relationship between the share of businesses closed during the first lockdown and the share of female workers in each sector.

The Contribution of Pre-pandemic Employment Sectors to the Employment Gender Gap. Panel (a) shows the economic sectors in which our respondents were employed pre-pandemic by the share of female workers hosted before the pandemic and the share of businesses that were closed during the first lockdown in May 2020. Markers are proportional to the number of workers employed in each sector before the pandemic. The slope of the fitted line is 0.55 (standard error: 0.12). See the notes to Table 1 for a detail of the occupations included in “Other Skilled” and “Other Unskilled”. Panel (b) illustrates average employment rates over time for male, female, and sector-reweighted female respondents. Sector-reweighted female employment rate is equal to female employment rate after weighting the female sample so that the first moment of Hit Sectori, an indicator for whether pre-pandemic the respondent was employed in a severely hit sector, matches that in the male sample. Weights are equal to one for male workers. Severely hit sectors are sectors in which more than 50% of the businesses in which our workers were employed pre-pandemic were closed during the first lockdown in May 2020: motor-mechanics, food and hotel, tailoring, hairdressing, teaching, secretary, and retail. 95% robust confidence intervals are reported

Figure 18 shows that such relationship was still positive in July 2020, despite all restrictions had been lifted. By May 2021 the curve had almost flattened, only to tilt again during the second lockdown in July 2021 even though businesses were not directly prevented from operating. A smaller rebound of labor demand and supply in female-dominated sectors may explain these dynamics. Fear of infection may have pushed customers to postpone the consumption of non-essential services or shift to home production. The lower purchasing power registered among the (mostly) female clients of firms in female-dominated sectors, documented in our study by the lower female earnings as well as in other contexts (Bau et al., 2022; Dang & Viet Nguyen, 2021; Hill & Köhler, 2021; Martinez-Bravo & Sanz, 2021) may have further depressed the demand of female products and services. Moreover, women may have decided not to go back to work when presented with the possibility, due to the close interactions with clients in female-dominated sectors paired with their higher fear for the virus.

To rigorously assess the role of employment sectors over time, we reweight the female sample so that the distribution of female workers across sectors that were severely and mildly hit by initial closures matches that of male workers.Footnote 10 Since women were over-represented in severely hit sectors, this procedure assigns large weights to women previously employed in mildly affected sectors. Panel (b) of Fig. 6 compares actual female and male employment rates with sector-reweighted female employment rate. The latter represents the female employment rate we would observe if, pre-pandemic, women were distributed across severely and mildly hit sectors as men. Sector-reweighted female employment rate is substantially higher than actual female employment rate during the first lockdown, but their distance declines over time. For each pandemic period, Table 7 measures the employment gender gap (Panel [a]) and quantifies the share of the gap explained by employment sectors (Panel [b]), calculated as the ratio of the gap between sector-reweighted and actual female employment rates and the gap between male and female employment rates. We concurrently show that this procedure is practically equivalent to calculating the share of the gender gap explained by different endowments using the standard decomposition proposed by Oaxaca (1973) and Blinder (1973) and the indicator for respondent’s pre-pandemic employment in severely hit sectors as explanatory variable. Initial closures in economic sectors explain 50% of the gap during the first lockdown in May 2020. Their contribution gradually declines following the easing of the restrictions, but rises once again during the second lockdown in July 2021, when it reaches 13%.

Because these economic sectors in Uganda are segregated by gender, there may be other unobserved sectorial characteristics, such as differences in reopening times or in the rebound of labor demand, that account for the residual part of the gap but are inseparable from gender. To test this hypothesis, Fig. 19 shows the average employment rate for male and female workers trained in single-gender or mixed-gender sectors. Men and women have the same average employment regardless of the gender composition of their sector, which is evidence against the existence of unobserved sectorial characteristics explaining the gender gap. The gendered employment dynamics we observe may still be driven by the systematic assignment of women and men to different tasks within sectors. We cannot test this hypothesis directly, but the high degree of specialization of our respondents and the absence of gender disparities in baseline employment quality point against this supposition.

4.4.2 The role of childcare responsibilities

That the availability and cost of childcare affect adult labor supply and business profitability for women is widely documented (Bjorvatn et al., 2022; Delecourt and Fitzpatrick 2021; Heath, 2017). We therefore investigate the contribution of childcare responsibilities, magnified by the prolonged schools’ closure, to the emergence and persistence of the employment gender gap. We use the number of school-age children in the household as a proxy for a respondent’s childcare responsibilities. This measure, following Alon et al. (2022), takes into account that our respondents may live with other young family members, such as siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews, on top of their own children. Additionally, as our sample is relatively young and the suspension of pre-primary schooling throughout the study period was especially salient, we define school-age children as children aged three or more. Using this definition, 42% of the respondents live with school-age children. Panel (a) of Fig. 7 shows female and male average employment rates by the number of school-age children in the household in periods in which schools were open (pre-pandemic) and closed (post-pandemic). Female employment declines with the number of school-age children in the household, but only during schools’ closure: the presence of one child reduces female employment by 5 p.p.; additional children further reduce it by 5 p.p. This negative relationship is not observed when schools are open. Conversely, male employment does not change with the number of school-age children they live with neither when schools are open nor when they are closed. We formally test for these differences by regressing employment on a constant and indicators for zero (omitted category), one, and two or more school-age children in the household separately for men and women. We report the estimated coefficients in Table 12. Columns (3) and (4) show that, both when schools are open and when they are closed, the differences in employment for men living with and without school-age children are small (0.1–2.8 p.p.) and insignificant. By contrast, columns (9) and (10) show that female employment declines more steeply with the number of school-age children in the household in periods in which schools are closed relative to periods in which they are open. When schools are open, women living with any number of school-age children are 4.9–5.6 insignificant p.p. less likely to be employed than women with none. When schools are closed, relative to women living with no school-age children, women living with one are 5.4 insignificant p.p. less likely to be employed, and women living with two or more are 9.6 significant (at 5% level) p.p. less likely to be employed. The same patterns emerge in columns (5), (6), (11), and (12), when we use the number of children aged six or more, hence attending primary or secondary schools, as alternative proxy for childcare responsibilities. In columns (1), (2), (7), and (8) we proxy childcare responsibilities with the total number of children in the household to consider the possibility that babysitting services for younger kids became inaccessible during the pandemic. We find that female employment declined with childcare responsibilities in a similar way when schools are open and when they are closed. This pattern corroborates our hypothesis that the prolonged closure of schools is the main driver of the observed dynamics. Additionally, as a given number of children may reflect different household compositions, we plot in Fig. 20 average female and male employment rates by bins of the ratio of the number of school-age children to the number of adults in the household. Our results remain consistent when incorporating the presence of other adults in the household with whom the respondent may share childcare responsibilities. Overall, this evidence corroborates our finding that schools’ closure disproportionately limited women’s self-reported ability to work due to the magnified childcare duties it generated (Panel [e] of Table 9).

The Contribution of Childcare Responsibilities to the Employment Gender Gap. Panel (a) displays the average employment rate for female and male respondents with zero, one, and two or more school-age children in the household in periods in which schools were open (January and March 2020) and periods in which schools were closed (May, July and December 2020, May, July and September 2021). School-age children are children aged 3 or more. Among women with non-missing information about the number of school-age children in the household, 89 have zero, 47 have one, and 79 have two or more. Among men with non-missing information about the number of school-age children in the household, 229 have zero, 50 have one, and 59 have two or more. Panel (b) illustrates average employment rates over time for male, female, and children-reweighted female respondents. Children-reweighted female employment rate is equal to female employment rate after weighting the female sample so that the proportions of respondent with zero, one, or more than one school-age children in the household match those in the male sample. 95% robust confidence intervals are reported

To quantify the contribution of childcare responsibilities to the emergence and the persistence of the employment gender gap, we reweight the female sample so that the proportions of respondents with zero, one, and more than one school-age children in the household match those in the male sample. Panel (b) of Fig. 7 compares female and male actual employment rates with children-reweighted female employment rate. The latter represents the female employment rate we would observe if women lived with the same number of school-age children as men. The figure shows that children-reweighted female employment rate is similar to actual female employment rate in the early stage of the pandemic but becomes higher over time. Panel (c) of Table 7 calculates the share of the employment gender gap explained by different childcare responsibilities by gender. This share is obtained, first, by dividing the gap between children-reweighted and actual female employment rates by the gap between male and female employment rates, and second, as the share of the gender gap explained by different endowments with a Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition in which we use indicators for living with zero, one and two or more school-age children as explanatory variables. The two methods consistently show that different childcare responsibilities have no explanatory power around the first lockdown, but explain between 11 and 24% of the employment gender gap from December 2020 onwards. These estimates would represent a lower bound for the true contribution of childcare responsibilities if our proxy, the number of school-age children in the household, underestimated true responsibilities for women and overestimated them for men. Overall, this evidence points towards initial job losses being mostly unrelated to schools’ closure, which contrarily limited females’ employment in the longer run.

Consistent with findings from the US (Hansen et al., 2022) and Kenya (Biscaye et al., 2022), we expect female employment to increase following the reopening of schools in January 2022. However, the fact that the Kenyan labor supply response was partly driven by the fall in agricultural child labor, the small portion of the employment gap explained by childcare responsibilities in our sample, and the 15-p.p. employment gap among respondents living with zero school-age children shown in panel (a) of Fig. 7, together suggest that in our urban context the employment gap will not close following the reopening.

4.4.3 The residual employment gender gap

Despite their extensive contributions, neither employment sectors nor childcare responsibilities manage to fully explain the employment gender gap in any period. We thus turn to investigating their joint contribution. As a first approach, we sum in each period the individual contributions of these two factors, reported in Panels (b) and (c) of Table 7, whenever they are both positive. The sum gives a sensible estimate of the joint contribution of employment sectors and childcare responsibilities so long as these two factors are independent in the female sample. For example, if women with fewer school-age children were also mostly employed in mildly hit sectors pre-pandemic, we would overestimate the share of the gap explained by each factor individually and hence, by taking their sum, their joint contribution. Conversely, if women with fewer school-age children were mostly employed in severely hit sector, we would underestimate the share of the gap explained by each factor individually and thus their joint contribution. Figure 21 illustrates that employment sectors and childcare responsibilities are independent among women: panel (a) shows that the distribution of school-age children in the household is almost identical in the original female sample and in the sample of women reweighted to match men’s sectorial distribution; panel (b) shows that the distribution of respondents in severely and mildly hit sectors is almost identical in the original female sample and in the female sample reweighted to match men’s childcare responsibilities. As childcare responsibilities contribute negatively to the employment gender gap in May and July 2020, and as employment sectors contribute negatively to the gap in December 2020 and May 2021, the sum of the independent contributions of childcare responsibilities and employment sectors is only informative in July and September 2021, during and after the second lockdown. Together, childcare responsibilities and employment sectors explain 37% and 21% of the employment gender gap in these periods. Based on this approach, between 50% and 85% of the gap remains unexplained by these two factors.

A second approach to calculating the joint contribution of employment sectors and childcare responsibilities consists in comparing female employment rate to the employment rate of counterfactual female respondents with the most advantageous traits in terms of both employment sectors and childcare responsibilities. Figure 8 shows, together with female and male employment rates, the employment rates of women in mildly hit sectors, reweighted to match men’s distribution of school-age children in the household, and of women with no school-age children in the household, reweighted to match men’s distribution across severely and mildly hit sectors. By relying on the smaller samples of women employed in mildly hit sectors and women with no school-age children in the household, this approach delivers relatively more imprecise estimates. As a result, in some periods we cannot reject the hypothesis that the employment rates of these counterfactual women are equal to both female and male employment rates. Despite the relatively lower power of this analysis, the point estimates suggest that an employment gender gap emerged and endured over time even for these highly advantaged counterfactual women. Panel (d) of Table 7 calculates the share of the employment gender gap jointly explained by employment sectors and childcare responsibilities in each period by dividing the difference between the employment rates of children-reweighted women working in mildly hit sectors and women by the employment gender gap (option 1), and by dividing the difference between the employment rates of sector-reweighted women without school-age children and women by the employment gender gap (option 2). Consistent with the large role played by employment sectors during the lockdowns, the employment rate of children-reweighted women working in mildly hit sector lies above female employment rate in May 2020 (lockdown 1), when 65% of the employment gender gap disappears, and in July 2021 (lockdown 2), when 39% disappears. In the remaining periods, the difference between these counterfactual and original female respondents declines. And consistent with the larger contribution of childcare responsibilities in the later pandemic periods, the employment rate of sector-reweighted women living with no school-age children lies above female employment rate in December 2020 and in July and September 2021, when 42%, 52% and 25% of the employment gender gap disappears respectively. In the earlier periods, these counterfactual and original women behave similarly. We thus estimate that, in each period, between 35% and 100% of the employment gender gap remains unexplained by employment sectors and childcare responsibilities.

The Residual Gender Gap in Employment. The figure illustrates average employment rates over time for male respondents, female respondents, sector-reweighted female respondents with no school-age children in the household, and children-reweighted female respondents that pre-pandemic were working in mildly hit sectors. There are 89 women with no school-age children in the household and non-missing data about employment sector. Sector-reweighted employment rate for women with no children is equal to the employment rate of women with no school-age children after weighting them so that the first moment of Hit Sectori, an indicator for whether pre-pandemic the respondent was employed in a severely hit sector, matches that in the male sample. Severely hit sectors are sectors in which more than 50% of the businesses in which our workers were employed pre-pandemic were closed during the first lockdown in May 2020: motor-mechanics, food and hotel, tailoring, hairdressing, teaching, secretary, and retail. There are 32 women in mildly hit sectors and with non-missing data about the number of school-age children in the household. Children-reweighted employment rate for women in mildly hit sector is equal to the employment rate of women with Hit Sectori=0 after weighting them so that the proportions of respondents with zero, one, and two or more school-age children in the household matches that in the male sample. School-age children are children aged three or more. Weights are equal to one for men. 95% robust confidence intervals are reported. Since there are only fifteen women in the sample employed in mildly hit sectors pre-pandemic and with no school-age children in the household, we are unable to use them in this analysis

To identify additional contributors to the residual employment gender gap, Fig. 22 investigates the existence of heterogeneities in the gendered effect of the pandemic on employment rate by several baseline characteristics. Regardless of the dimension by which we split the female and male samples, and despite the lower power due to these additional divisions, we keep observing the same employment dynamics. The absence of heterogeneities by own and household asset ownership suggests that the decline in female employment is not driven by women who could not afford childcare or earning less than their partners. Additionally, there is no heterogeneity by fear of COVID-19 infection. Alternative explanations, then, include women complying more with COVID-19 restrictions (Galasso et al., 2020; Oreffice & Quintana-Domeque, 2021), employers’ discrimination in layoffs and hirings, and social norms reducing female attachment to the labor market (Jayachandran, 2021). Understanding the residual forces behind the rise and the persistence of the employment gender gap is essential to design effective countermeasures.

5 Conclusions

We analyze the gendered labor market effects of the COVID-19 induced restrictions on a sample of young and skilled Ugandan workers and entrepreneurs employed in a wide range of vocational industries. With a unique high-frequency panel dataset spanning from January 2020 to September 2021, we identify short- and long- term responses to two lockdowns implemented in Uganda. These restrictions disproportionately reduced female employment, shifted female workers into self-employment and into sectors misaligned with their skill sets, and widened the gender pay gap. While men quickly restored their pre-pandemic labor market trajectories, almost half of the previously employed women found more precarious occupations or became jobless. Together, our findings indicate that hard-earned progress towards women’s employment and earnings parity can be set back by temporary shocks. To explain the uneven impact and recovery, we decomposed the employment gender gap to quantify the role of women’s pre-pandemic sorting in severely hit sectors and increased childcare responsibilities due to schools’ closure. These factors explain up to 65% of the employment gap; the rest remains unexplained, creating additional barriers to devise effective countermeasures.

Our sample represents a small yet growing share of the Ugandan population. Given the importance of this population for the country’s transition into a middle-income economy, the persistence of an employment gap eighteen months from the COVID-19 shock should be of great concern to policymakers. The decline in female skilled employment and the sectorial misallocation induced by the pandemic may slow the country’s structural transformation. Given the precarious nature of economic development, Uganda’s stakeholders should prioritize policies supporting women seeking to reenter the labor market and provide targeted support for enterprises in sectors with higher female representation.

Notes

Adams-Prassl et al. (2020); Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2023); Deshpande (2022); Farré et al. (2022); Heggeness (2020); Kristal and Yaish (2020); Andrew et al. (2022); Casale and Posel (2021); Dang and Viet Nguyen (2021); Kikuchi et al. (2021); Landivar et al. (2020); Reichelt et al. (2021); Kugler et al. (2023); Alon et al. (2022); and Casale and Shepherd (2022) find disproportionate effects of the economic restrictions on female workers. Torres et al. (2021); Gulesci et al. (2021); and Alfonsi et al. (2021) focus on entrepreneurs.

Authors’ elaboration of the latest Uganda National Household Survey from 2016/2017.

Exceptionally, schools reopened in October 2020 for students enrolled in the last year of their education cycle.

Like most Ugandan VTIs, none of these five tracked their graduates’ career developments nor kept their updated contacts. We therefore collected and digitized schools’ hard copies of registries for multiple cohorts of graduates, obtained contacts for 1368 alumni, and successfully contacted 52% of them. Our sample is not evidently selected with respect to the eligible population: due to the written nature and manual entry of the records, the digitization process was prone to error; additionally, the progressive implementation of the 2013 mandate of the Uganda Communication Commission to register all SIM-cards exogenously pushed many to change their phone numbers. Figure 9 shows an example of the digitized material.

This work was implemented in partnership with BRAC Uganda as a spin-off study of the Meet Your Future Project (Alfonsi et al., 2023), a randomized control trial connecting graduating vocational students with successful alumni of their schools to facilitate students’ transition into the labor market. The respondents of this study represent the pool of alumni from which we selected 154 young professionals who participated to the project as mentors for the students. To identify successful alumni who could provide quality mentorship to the students, we collected detailed information about their demographics, education, and work experience. Some of the variables we collected to make the selection are also primary outcomes in this study. There is no reason to believe that our respondents manipulated their answers to increase their chances to be selected. First, because the selection was based on merit but also on the goal to recruit mentors for each combination of school and course of study for which we had students, reducing the competition based on personal traits. Second, because the symbolic compensation and travel reimbursement we promised to respondents selected as mentors were likely insufficient to generate misreporting incentives, especially when weighted against the significant time and commitment that mentors put into preparation and actual implementation of the program. Third, because we elicited respondents’ broad interest in the project without informing them about the selection criteria. Hence, they were in practice unable to manipulate their score. Additionally, given our effort to find male and female mentors in similar fashion, there is no reason to believe that misreporting incentives differed by gender. Our findings are robust to excluding the respondents who served as mentors in the Meet Your Future Project from the sample.

The possibility that our respondents suffered from recollection bias is the main risk from using retrospective information. If true, we could overstate the autocorrelation between outcomes over time (Godlonton et al., 2018), and the existence of a gender gap in our outcomes at the time of measurement may lead us to overestimate the gap in recollected periods. To explain this point, suppose that the employment rate is lower for women than for men at time T, when there is no reporting bias. Then, women would be more likely, due to recollection bias, to say they were not employed in T-1; the opposite would be true for men, and we would overstate the employment gender gap in T-1. There are, however, several reasons why recollection bias is likely limited in our context. First, recollection bias is more pronounced among poor individuals (Das et al., 2012), while our respondents belong to the top tail of the education and income distribution in Uganda. Second, salient events are less subject to recollection bias (Beegle et al., 2012; Das et al., 2012). We structured our questionnaire to clearly identify moments before, during, or after the two nationwide lockdowns, which were disruptive events with tremendous consequences on the lives of our respondents and far beyond. We thus believe that our respondents accurately tracked their labor market outcomes around the lockdowns. Additionally, even if the recollected data points were considered unreliable and dropped from our analysis, all our conclusions would still apply.

In our data we cannot distinguish unemployed and not economically active individuals.

This dynamic is consistent with the positive association between employment and age found for vocational graduates of both genders in the UNHS (panel [a] of Fig. 11).

We reweight the female sample so that the average of Hit Sectori matches the male sample average. Hit Sectori is an indicator equal to one for respondents that pre-pandemic were employed (or trained, if non-employed) in a sector in which more than 50% of our respondents’ pre-pandemic businesses were closed during the first lockdown: motor-mechanics, food and hospitality, tailoring, hairdressing, teaching, secretary, and retail. Weights are equal to one for men.

References

Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M. & Rauh, C. (2020). Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: Evidence from Real Time Surveys. Journal of Public Economics 189.

Alfonsi, L., Bandiera, O., Bassi, V., Burgess, R., Rasul, I., Sulaiman, M., & Vitali, A. (2020). Tackling youth unemployment: Evidence from a labor market experiment in Uganda. Econometrica, 88, 2369–2414.

Alfonsi, L., Bassi, V., Manwaring, P., Ngategize, P., Oryema, J., Stryjan, M., & Vitali, A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on Ugandan firms: Evidence from recent surveys and policy actions for supporting private sector recovery. IGC Policy Brief

Alfonsi, L., Namubiru, M. & Spaziani, S. (2023). Meet Your Future: Experimental Evidence on the Labor Market Effects of Mentors. Working Paper.

Allard, J., Jagnani, M., Neggers, Y., Pande, R., Schaner, S., Moore, C. T. (2022). Indian female migrants face greater barriers to post-Covid recovery than males: Evidence from a panel study. eClinicalMedicine 53, p. 101631.

Alon, T., Doepke, M., Manysheva, K. & Tertilt, M. (2022). Gendered Impacts of Covid-19 in Developing Countries. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 112, 272–76.

Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J. & Tertilt, M. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality. NBER Working Paper 26947, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Marcén, M., Morales, M. & Sevilla, A. (2023). Schooling and Parental Labor Supply: Evidence from COVID-19 School Closures in the United States. Industrial and Labor Relation Review, 76, 56–85.

Andrew, A., Cattan, S., Costa Dias, M., Farquharson, C., Kraftman, L., Krutikova, S., Phimister, A., Sevilla, A. (2022). The gendered division of paid and domestic work under lockdown. Fiscal Studies, 43, 325–340.

Bandiera, O., Niklas, B., Robin, B., Markus, G., Selim, G., Imran, G. & Munshi, S. (2020). Women’s empowerment in action: Evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12, 210–59.

Bau, N., Khanna, G., Low, C., Shah, M., Sharmin, S., Voena, A. (2022). Women’s well-being during a pandemic and its containment. Journal of Development Economics 156.

Beegle, K., Carletto, C., & Himelein, K. (2012). Reliability of recall in agricultural data. Journal of Development Economics, 98, 34–41. Symposium on Measurement and Survey Design.

Biscaye, P. E., Egger, D. & Pape, U. J. (2022). Balancing Work and Childcare: Evidence from COVID-19 Related School Closures in Kenya. Working Paper.

Bjorvatn, K., Denise, F., Selim, F., Arne, N., Vincent, S., & Lore, V. (2022). Childcare, labor supply and business development: Experimental evidence from Uganda. Working Paper.

Blinder, A. S. (1973). Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources, 8, 436–455.

Bluedorn, J., Caselli, F., Hansen, N.-J., Shibata, I., & Tavares, M. M. (2023). Gender and employment in the COVID-19 recession: Cross-Country evidence on “She-Cessions”. Labour Economics, 81.

Casale, D. & Posel, D. (2021). Gender Inequality and the COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from a Large National Survey during South Africa’s Lockdown. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 71.

Casale, D., & Shepherd, D. (2022). The gendered effects of the covid-19 crisis in south africa: Evidence from nids-cram waves 1–5. Development Southern Africa, 0, 1–20.

Couch, K. A. (2020). Gender and the COVID-19 labor market downturn. Working Paper.

Dang, H.-A. H., & Viet Nguyen, C. (2021). Gender inequality during the covid-19 pandemic: Income, expenditure, savings, and job loss. World Development, 140, 105296.

Das, J., Hammer, J., & Sánchez-Paramo, C. (2012). The impact of recall periods on reported morbidity and health seeking behavior. Journal of Development Economics, 98, 76–88.

Del Boca, D., Oggero, N., Profeta, P., & Rossi, M. (2020). Women’s and men’s work, housework and childcare, before and during covid-19. Review of Economics of the Household, 18, 1001–1017.

Delecourt, S., & Fitzpatrick, A. (2021). Childcare matters: Female business owners and the baby-profit gap. Management Science, 67, 4455–4474.

Deshpande, A. (2022). The Covid-19 pandemic and gendered division of paid work, domestic chores and leisure: evidence from India’s first wave. Economia Politica, 39, pp. 75–100.

EPRC. (2021). Employment creation potential, labor skills requirements and skill gaps for young people. a uganda case study. Tech. Rep.

Farré, L., Fawaz, Y., González, L. & Graves, J. (2022). Gender Inequality in Paid and Unpaid Work During Covid-19 Times. Review of Income and Wealth, 68, 323–347.

Foucault, M. & Galasso, V. (2020). Working After Covid-19: Cross-Country Evidence from Real-Time Survey Data. Sciences Po publications 9, Sciences Po.

Furman, J., Kearney, M. S. & Powell, W. (2021). The role of childcare challenges in the us jobs market recovery during the covid-19 pandemic. Working Paper 28934, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Galasso, V., Pons, V., Profeta, P., Becher, M., Brouard, S., & Foucault, M. (2020). Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117, pp 27285–27291.

Ghanem, D., Hirshleifer, S., & Karen, O.-B. (2023). Testing for Attrition Bias in Field Experiments. Journal of Human Resources, 58, 5.

Godlonton, S., Hernandez, M. & Murphy, M. (2018). Do you remember? measuring anchoring bias in recall data. Tech. Rep., IFPRI.

Gulesci, S., Loiacono, F., Madestam, A. & Stryjan, M. (2021). COVID-19, SMEs, and workers: Findings from Uganda. IGC Final Report.

Hansen, B., Sabia, J. J. & Schaller, J. (2022). Schools, job flexibility, and married women’s labor supply: Evidence from the covid-19 pandemic. Working Paper 29660, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heath, R. (2017). Fertility at work: Children and women’s labor market outcomes in urban Ghana. Journal of Development Economics, 126, 190–214.

Heggeness, M. L. (2020). Estimating the immediate impact of the covid-19 shock on parental attachment to the labor market and the double bind of mothers. Review of Economics of the Household, 18, 1053–1078.

Hill, R. & Köhler, T. (2021). Mind the gap: The distributional effects of South Africa’s national lockdown on gender wage inequality. DPRU Working Paper, 202101.

Horowitz, J. L., & Manski, C. (2006). Identification and Estimation of Statistical Functionals using Incomplete Data. Journal of Econometrics, 132, 445–459.

Hsieh, C.-T., Hurst, E., Jones, C. I., & Klenow, P. J. (2019). The allocation of talent and u.s. economic growth. Econometrica, 87, 1439–1474.

Hupkau, C., & Petrongolo, B. (2020). Work, Care and Gender during the COVID-19 Crisis. Fiscal Studies, 41, 623–651.

ILO (2017). Uganda swts country brief. Tech. Rep.

ILO (2022). Ilo monitor on the world of work. 9th edition. Tech. Rep.

ILO (2022). World employment and social outlook. trends 2022. Tech. Rep.

International Youth Foundation. (2011). Navigating challenges. charting hope. a cross-sector situational analysis on youth in uganda. Tech. Rep.

Jayachandran, S. (2021). Social Norms as a Barrier to Women’s Employment in Developing Countries. IMF Economic Review, 69.

Kikuchi, S., Kitao, S., & Mikoshiba, M. (2021). Who suffers from the covid-19 shocks? labor market heterogeneity and welfare consequences in japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 59, 101117.

Kling, J. R., Liebman, J. B., & Katz, L. F. (2007). Experimental Analysis of Neighborhood Effects. Econometrica, 75, 83–119.

Kristal, T. & Yaish, M. (2020). Does the Coronavirus Pandemic Level the Gender Inequality Curve? (It Doesn’t). Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 68.

Kugler, M., Newhouse, D., Viollaz, M., Duque, D., Gaddis, I., Palacios-Lopez, A., & Weber, M. (2023). How Did the COVID-19 Crisis Affect Different Types of Workers in the Developing World? World Development, 170.

Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., Scarborough, W. J., & Collins, C. (2020). Early signs indicate that covid-19 is exacerbating gender inequality in the labor force. Socius, 6.

Lee, S. Y. T., Park, M. & Shin, Y. (2021). Hit harder, recover slower? Unequal employment effects of the covid-19 shock. Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, 103.4, 367–383.

Liang, X., Rozelle, S., & Yi, H. (2022). The impact of covid-19 on employment and income of vocational graduates in china: Evidence from surveys in january and july 2020. China Economic Review, 75, 101832.

Martinez-Bravo, M., & Sanz, C. (2021). Inequality and psychological well-being in times of COVID-19: evidence from spain. SERIEs, 12, 489–548.

Montenovo, L., Jiang, X., Lozano Rojas, F., Schmutte, I., Simon, K. I., Weinberg, B. A., & Wing C, (2022). Determinants of Disparities in Early COVID-19 Job Losses. Demography, 59, 3, pp. 827–855.

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14, 693–709.

OECD. (2020). Job retention schemes during the covid-19 lockdown and beyond. Tech. Rep.

Oreffice, S., & Quintana-Domeque, C. (2021). Gender inequality in covid-19 times: evidence from uk prolific participants. Journal of Demographic Economics, 87, 261–287.

Papageorgiou, M. C., Espinoza, M. R. A., Alvarez, J. & Ostry, M. J. D. (2018). Economic Gains From Gender Inclusion: New Mechanisms, New Evidence. IMF Staff Discussion Notes 2018/006, International Monetary Fund.

Reichelt, M., Makovi, K., & Sargsyan, A. (2021). The impact of covid-19 on gender inequality in the labor market and gender-role attitudes. European Societies, 23, S228–S245.

Sevilla, A., & Smith, S. (2020). Baby Steps: The Gender Division of Childcare during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36, S169–S186.

Stantcheva, S. (2022). Inequalities in the times of a pandemic. Economic Policy, 37, 5–14.

Torres, J., Maduko, F., Gaddis, I., Iacovone, L. & Beegle, K. (2021). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women-Led Businesses. Working Paper.

World Bank (2021). Uganda economic update. from crisis to green resilient growth: Investing in sustainable land management and climate smart agriculture. Working Paper.

Zamarro, G., & Prados, M. J. (2021). Gender differences in couples’division of childcare, work and mental health during covid-19. Review of Economics of the Household, 19, 11–40.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gaia Dossi, Andrew Foster, Supreet Kaur, Eliana La Ferrara, John Friedman, Selim Gulesci, Jeremy Magruder, Ted Miguel, Jonathan Roth, Elisabeth Sadoulet, Bryce Steinberg, Matthew Suandi, Diego Ubfal, Christopher Walters, seminar participants at the Berkeley Development Lunch and Development Therapy, the Brown University Development Tea, Applied Microeconomics Breakfast and Applied Microeconomics Lunch, the LEAP Alumni conference, the NEUDC conference, and the PacDev conference, and two anonymous referees for very insightful conversations and suggestions. Marco Lovato and Irina Vlasache provided excellent research assistance. We received IRB approval from UC Berkeley. A previous version of this paper circulated under the title “The Gendered Impacts of Covid-19: Evidence from the Ugandan Shecession”. All errors are our own.

Funding

This work is supported by the International Development Research Centre via the BRAC-CEGA Learning Collaborative Secretariat; the IZA and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office via the IZA/FCDO Gender, Growth and Labour Markets in Low Income Countries Programme (G2LIC∣IZA) [grant agreement GA-5-696]; the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University; the Orlando Bravo Center for Economic Research at Brown University; and the Institute for Research on Labor Economics at UC Berkeley. Our sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests