Abstract

This paper analyzes the role of mental health in self-employment decisions. We find evidence of a relationship between psychological distress and self-employment for men that depends on type of self-employment and severity of psychological distress. Specifically, there is suggestive evidence of a causal link from moderate psychological distress to self-employment in an unincorporated business as a main job for men. Additionally, we find evidence that long term mental illness can significantly increase the probability of self-employment in an unincorporated business for both men and women. Our results suggest that individual difficulty in wage-and-salary employment is the likely mechanism for this connection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurship has been shown to drive economic growth (Baumol, 1996), at least partially because new businesses create jobs at a much higher rate than established firms (Haltiwanger et al., 2008). Due to the importance of entrepreneurship to the economy, the traits of successful entrepreneurs have been intensely studied and documented by academics and business people alike. Historically, the most discussed characteristic of entrepreneurs has been attitude toward risk. Individuals have a choice between becoming workers for established firms or starting their own firm; in equilibrium, models predict that individuals who are less risk averse become entrepreneurs (Ekelund et al., 2005; van Praag & Cramer, 2001; Kihlstrom & Laffont, 1979; Knight, 1965). This is not surprising given that the success rate of entrepreneurs is very low. For example, about half of new firms do not survive more than five years (Small Business Association Office of Advocacy, 2012). Since mental illness and emotions have been shown to be correlated with risk attitudes (Maner et al., 2007; Fessler et al., 2004; Loewenstein et al., 2001), as well as numerous other characteristics of entrepreneurs that we will discuss below, we examine the relationship between self-employment and mental health status.

The theoretical and empirical literature on the self-employment choice problem has identified several characteristics that determine entrepreneurship. Factors such as education, age, race, marital status, and physical health have been shown to affect an individual’s probability of self-employment (Bogan & Darity, 2008; Del Boca et al., 2000; Evans & Leighton, 1989; Rees & Shah, 1986). Further, there is a large literature describing the “entrepreneurial” personality (See as an example Smith-Hunter et al. 2003). Studies find that key entrepreneurial characteristics include: risk propensity (Knight, 1965; Arenius & Minniti, 2005; Pendergast, 2003; Ekelund et al., 2005), creativity (Engle et al., 1997; Pendergast, 2003), achievement orientation (Collins et al., 2004; Pendergast, 2003), self-efficacy (Arenius & Minniti, 2005), persistence and independence (Pendergast, 2003). In addition, Baron (1999) shows that entrepreneurs are less likely than others to think about how things might have turned out differently in past situations. Cooper et al. (1988) find that the assessment by entrepreneurs of their own likelihood of success is dramatically detached from past macro statistics and the perceived likelihood of the success of their peer group. More recently, Hvide & Panos (2014) test and confirm that risk tolerant individuals are more likely to become entrepreneurs but perform worse. Further, Levin & Rubinstein (2017) show that “the combination of smart and illicit tendencies as youths accounts for both entry into entrepreneurship and the comparative earnings of entrepreneurs.”

Several of these characteristics overlap with defining characteristics of mental illness and the effects of mental illness. There is anecdotal support for this view. For example, famous entrepreneur, Elon Musk, has been identified as having bipolar disorder and Kate Spade suffered from anxiety and depression.Footnote 1 Bipolar disorders symptomatically involve taking on new projects, increasing high-risk behaviors, and having unrealistic beliefs in one’s abilities (National Institute of Mental Health, 2013) and depression and anxiety disorders are common among high-achieving individuals (Kawamura et al., 2001). In the literature, Tremblay et al. (2010) find that those with bipolar disorder appear to be disproportionately concentrated in more creative occupations. Further, Freeman et al. (2019) find that entrepreneurs experience more depression (30%) and bipolar disorder (11%) than comparison participants. Thus, with regard to the relationship between entrepreneurship and mental illness, there may be a “pull effect”—characteristics associated with mental illness could be valuable traits to have as an entrepreneur. It could be the case that entrepreneurship matches well with the comparative advantages of people with mental health problems.

In contrast to the “pull effect” described above, there may be a “push effect”—some forms of mental illness may make wage-and-salary employment more difficult. Symptoms of depression, for example, include loss of interest in activities; fatigue and decreased energy; difficulty concentrating, remembering details, and making decisions (National Institute of Mental Health, 2013). As a result, individuals suffering from depression or other forms of mental illness have lower earnings than healthy individuals (Cseh, 2008; Ettner et al., 1997; Bartel & Taubman, 1986), and thus lower opportunity costs associated with being an entrepreneur.

The economic literature supports the view that individuals who are disadvantaged in the wage-and-salary labor market are more likely to choose self-employment. For example, Clain (2000) finds that women who choose full-time self-employment have personal characteristics that are less highly valued in the marketplace than women who work full-time in wage-and-salary employment. Moreover, it has been documented that immigrant disadvantages play a role in immigrant self-employment. For some immigrant groups, small business offers an alternative to low-paying, menial jobs in the secondary sector (Min, 1988). Similarly, those with mental health problems may have characteristics that cause them to more often choose self-employment over wage-and-salary employment.

Hessels et al. (2017) find that the self-employed experience less work-related stress than wage-and-salary employees and that self-employed individuals without employees experience less work-related stress than those with employees, due to a lower level of job demand. However, much of the entrepreneurship literature suggests that entrepreneurship is a stress-inducing occupation which in turn creates physical and mental health problems (Buttner, 1992; Jamal, 1997). While Stephan & Roesler (2010) find evidence that an entrepreneurial career may have some health benefits, Rietveld et al. (2015) show that the selection of comparatively healthier individuals into self-employment accounts for the positive cross-sectional difference. Further, Rietveld et al. (2015) present evidence that engaging in self-employment has a negative effect on health.

This paper builds upon the work of Levine & Rubinstein (2017) who find that incorporated business owners as teenagers scored higher on learning aptitude tests and were engaged in more aggressive, illicit, risk-taking activities than unincorporated business owners and the work of Astebro et al. (2011) whose model of occupational choice predicts self-employed individuals are disproportionately drawn from the tails of the earnings and ability distribution. This literature suggests that those with valuable traits to have as an entrepreneur (one tail of the ability distribution) become incorporated business owners while those with difficulties in the wage-and-salary employment market (the other tail of the ability distribution) become unincorporated business owners. In this context, our empirical analysis that includes an incorporated versus unincorporated business distinction, will enable us to address a lacuna in the literature with regard to potential mechanisms influencing the causal relationship between mental health and self-employment. Moreover, our study contributes to the literature by providing empirical support for the direction, magnitude, and nature of the relationship. Using a representative sample of Americans, we primarily focus on one specific aspect of mental health and analyze the effect of psychological distress on the decision to become self-employed and the type of self-employment chosen.

We find a connection between psychological distress and self-employment among men that is related to both the type of self-employment (unincorporated or incorporated business) and the severity of psychological distress. For men, there is causal evidence to suggest that having moderate psychological distress increases the probability of being self-employed in an unincorporated business as a main job. For both men and women, we find some evidence that long-term mental illness is associated with unincorporated self-employment as a main job. For women, we find that long-term mental illness also is associated with unincorporated self-employment as a secondary job. Given that pursuing self-employment in unincorporated businesses can be linked to wage-and-salary employment being more difficult (Levine & Rubinstein, 2017), the “push effect,” our results suggest that difficulty with wage-and-salary employment is the likely mechanism for the connection between psychological distress and self-employment.Footnote 2

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data. Section 3 discusses the empirical strategy and hypothesis development. Section 4 presents the econometric analysis and results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes key findings and provides concluding remarks.

2 Data

The data used in this study come from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) which is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of U.S. households.Footnote 3 The panel nature of the survey combined with the fact that it collects information on employment, mental health, and demographic characteristics, make it ideally suited for our analysis. Due to the data availability of mental health measures, we use data from the years 2001 through 2017.Footnote 4 We focus on only those respondents who are less than 75 years old. We do not impose any further age restrictions.Footnote 5

2.1 Subgroups

We separately study male and female PSID respondents.Footnote 6Footnote 7 We separate the sample in this way because empirical evidence shows that women have different labor market preferences than men with regard to self-employment. Boden (1996) shows that women’s propensity to select out of wage-and-salary employment and into self-employment trails that of men. Furthermore, Hundley (2000) concludes that women tend to choose self-employment to facilitate household production and men tend to choose self-employment to achieve higher earnings. In our data, a Chow test indicates that the coefficients for specifications using men are weakly significantly different than those for women (F = 1.51 with a p-value of 0.113). The labor market decisions of couples are generally made jointly, so we control for marital status within each sample (Lundberg et al., 2003; Kirchler et al., 2008).

We limit our sample by including only those who responded to the primary mental health measure that we use. This question is asked in 2001, 2003, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017. Also, only one person in a household (the interview respondent) provides responses for the mental health measure that we use. Thus, we only have one observation from each couple household. We begin with a sample of 67,289 person-year observations. We lose 24.6% of the sample by restricting the sample to only those observations with a lagged mental health measurement (n = 16,528). As mentioned previously, we drop those respondents over 75 years old (n = 2655 or 3.9%). We also limit the sample by omitting those who did not respond to the self-employment question (n = 44 or <0.1%) and those who did not respond to most of the control variables (n = 55 or <0.1%). This leaves us with a total sample of 48,007 person-year observations. Table 1 shows that our sample consists of 19,491 men-year observations, 28,516 women-year observations when all waves of data are pooled.

2.2 Employment measures

Levine & Rubinstein (2017) argue that self-employment should not be considered a homogeneous occupational classification and that there is a distinction between incorporated business owners (entrepreneurs) and unincorporated business owners (other business owners). The PSID data allow us to make this distinction between self-employment in incorporated and unincorporated businesses.Footnote 8

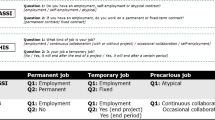

Our primary outcome variable is employment status, which is an unordered categorical variable with six possible values: (1) main job and any secondary jobs are all wage-and-salary employment; (2) main job (or a secondary job) is self-employment in an incorporated business;Footnote 9 (3) main job is self-employment in an unincorporated business; (4) main job is wage-and-salary employment with an unincorporated business as a secondary job; (5) unemployed; and (6) out of the labor force. As defined, these categories are mutually exclusive and summary statistics for these categories are presented in Table 2.Footnote 10

Table 2, Panel A shows that 63.8% of the male observations and 60.3% of the female observations have wage-and-salary employment, 6.1% of male and 6.0% of female observations are unemployed, and 15.7% of the male observations are out of the labor force (OLF) while 25.2% of the female observations are OLF. Thus, compared to women, men are more likely to have some self-employed observations (14.3% of observations vs. 8.5%). For both men and women, self-employment as the main job is more common than as a secondary job and unincorporated self-employment is more common than incorporated self-employment.

Panel B of Table 2 shows changes over time in main job self-employment status for men and women during the time period studied (2003–2017). Of the 4852 unique males that we observe over time, 19.1% report that they are self-employed in some interview waves but not all waves. Of the 8152 unique females followed over time, 12.4% report changes in self-employment status over time. Our analyses that involve conditional fixed effects will identify effects from this subgroup of the sample.Footnote 11

Tables 3 and 4 present employment transition matrices indicating changes in employment from one wave to the next. These tables illustrate the inertia in employment status from one wave to the next. Over 80% of men and over 78% of women in wage-and-salary jobs in one wave have wage-and-salary jobs in the next period. Similarly, about 60% of men and women who are OLF in one wave continue to be so in the next wave. The bold text in Tables 3 and 4 show substantial inertia in self-employment. Over 60% of men in incorporated self-employment jobs remain in some type of self-employment the following wave. Over 55% of men in main job unincorporated self-employment remain self-employed the following wave. Over 36% of men in secondary job unincorporated self-employment remain self-employed the following wave. This pattern is similar among self-employed women although the rates of staying self-employed are slightly lower than for men. We also can see that there is limited movement from unemployment to self-employment (10.7% for men and 7.9% for women) and very little movement from OLF to self-employment (7.1% for men and 5.0% for women). See italic text in Tables 3 and 4.

Most self-employment is concentrated within a few occupational categories. Table 5 reports the top self-employment occupational categories for our sample of individuals by gender and incorporation status. For each subsample, four categories encompass the top three from each of our self-employment groupings (incorporated self-employment, unincorporated self-employment as a main job, and unincorporated self-employment as a secondary job). For both men and women, we find the top categories include mostly low fixed cost businesses.

2.3 Mental health measures

In all waves from 2001 to 2017 except the 2005 wave, each respondent is asked a series of six questions about his/her current feelings. The questions ask the respondent to rate the following feelings on a scale of 0 (=none of the time) to 4 (=all of the time): whether he/she has felt sad, nervous, restless, hopeless, worthless, and that everything was an effort in the last 30 days. These question responses are summed to create the K-6 non-specific psychological distress score (Kessler et al., 2003), which has been shown to be a good predictor of depression and anxiety (Furukawa et al., 2003; Cairney et al., 2007). Because only the interview respondent can answer these questions, we do not observe the K-6 score for the spouse of a married respondent. Married respondents are fairly split between husbands (males) and wives (females) so we are able to examine the effect of the K-6 score for married males and married females, just not within the same household. The K-6 psychological distress screen is useful because the timing is specific, it can vary over time as symptoms come and go, it does not require a doctor diagnosis, and it captures mild as well as severe conditions (Andrews, 2001).Footnote 12

While the K-6 score is a continuous variable, we do not use it as a continuous variable in our analysis because there is a rich literature documenting its nonlinearity and identifying the appropriate cut-off points to use to categorize levels of psychological distress. Kessler et al. (2003) find that a K-6 score of 13 or higher indicates that the respondent suffers from severe psychological distress. As a result, we create a dummy variable from the score using this cutoff. We also create an additional dummy variable to capture moderate psychological distress (scores between 5 and 12 inclusive), since the effects of mood may not be limited to severe cases (Prochaska et al., 2012). Individuals with K-6 scores lower than 5 are considered not to have any psychological distress.Footnote 13 It is notable that using the K-6 measure enables us to focus on the relationship with one specific aspect of mental health - psychological distress (depression and anxiety).

The K-6 measure varies over time (See Table 6). In the sample, 60.2% of men and 56.1% of women always score below a five and 7.1% of men and 11.3% of women always score a five or above. We see 32.8% of the male subgroup and 32.5% of the female subgroup move between low and moderate/high scores over time. Consistent with these statistics, we find that the correlation between K-6 status from one wave to the next is positive (0.5586—men; 0.6063—women).

Table 7 provides summary statistics for the K-6 mental health measures used in this analysis by self-employment status. Significance tests indicate differences in the means compared to the wage-and-salary only group. For both men and women, main job unincorporated self-employment is associated with a lower percentage of respondents in the lowest K-6 category compared to the wage-and-salary only employment group (75.6% vs. 78.6% for men and 67.9% vs. 74.3% for women). The unincorporated self-employed also have a higher percentage of respondents being in the middle and high K-6 score categories than the wage-and-salary only employment group. In contrast, the self-employed in an incorporated business group has a higher percentage of respondents in the lowest K-6 category and a lower percentage of respondents in the middle and high K-6 score categories than the wage-and-salary employment only group.

Figure 1 presents the relationship between K-6 score level and self-employment rates by type of business for men and women. The relationship between K-6 score and self-employment differs by gender and the severity of psychological distress. For men, unincorporated self-employment as a main job rises as severe psychological distress increases. Unincorporated self-employment as a secondary job is relatively flat over the range of moderate psychological distress and then declines over the range of severe psychological distress. Incorporated self-employment declines over the range of moderate psychological distress scores and then is relatively constant over the range of severe psychological distress scores. For women, incorporated self-employment and unincorporated self-employment as a secondary job are relatively constant over the range of psychological distress scores. Unincorporated self-employment as a main job rises slightly over the range of moderate psychological distress scores and declines slightly over the range of high psychological distress scores.

2.4 Control variables

Table 8 provides summary statistics for salient characteristics of the individual and the household, capturing demographic traits, socioeconomic status, and physical health (Hvide & Panos, 2014; Astebro et al., 2011; Del Boca et al., 2000; Rees & Shah, 1986).Footnote 14 The demographic variables include age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and the number of biological children.Footnote 15 The variables that capture socioeconomic status are education, household net worth, whether they own their own home, and a financial distress indicator.

Household net worth includes financial assets, non-financial assets (including a primary residence), and retirement accounts. As a household member could have mental health problems because the household was in financial distress and this distress could influence job choice, we create a measure of financial distress to use as a control in the analysis. We calculate a financial distress scale for each household by dividing the value of household consumer debt by household income. Household consumer debt includes credit card charges, student loans, medical or legal bills, or loans from relatives but does not include any mortgage on a primary residence or vehicle loans. The scale goes from 0 to 1 where 1 is distressed.Footnote 16

Rees & Shah (1986) show that poor physical health decreases the probability of self-employment. Thus, we also control for physical health with a variable that counts the number of chronic conditions that a respondent reports from the following list of possible conditions: high blood pressure or hypertension; diabetes or high blood sugar; cancer or a malignant tumor (excluding skin cancer); chronic lung disease such as bronchitis or emphysema; coronary heart disease, angina or congestive heart failure; and arthritis or rheumatism. Poor physical health can negatively affect self-employment because access to health insurance is less likely. Thus, we also control for health insurance status and medical expenditures of the household.

Economic conditions also could have a large impact on both mental health and self-employment (Zivin et al., 2011). Consequently, we control for economic conditions using unemployment rate data which is a common macroeconomic indicator that previously has been used in the context of labor market decision research (Bedard & Herman, 2008; Boffy-Ramirez et al., 2013).Footnote 17 We link the annual, national, unemployment rate specific to the gender and race of each respondent.Footnote 18

3 Empirical strategy and hypothesis development

Consistent with much of the economic literature on occupational choice, we base our empirical analysis on a model which assumes that workers make occupational choice decisions to maximize expected utility (Blau, 1987). Occupational choice theory indicates that self-employment will be more attractive for individuals with low earnings potential in wage-and-salary employment or high earnings potential in self-employment. Astebro et al. (2011) develop a multi-task model of occupational choice in which frictions in the labor market induce mismatches between firms and workers, and misassignment of workers to tasks. Their model predictions are consistent with recent evidence which shows that entrants into self-employment are disproportionately drawn from the tails of the earnings and ability distributions (Astebro et al., 2011). Generally, we consider a framework in which differences (D*) in expected utility between self-employment and wage-and-salary employment are a function of observable personal characteristics:

Levine & Rubinstein (2017) find that incorporated business owners as teenagers scored higher on learning aptitude tests and were engaged in more aggressive, illicit, risk-taking activities than unincorporated business owners. This suggests that those with valuable traits to have as an entrepreneur (one tail of the ability distribution à la Astebro et al. (2011)) become incorporated business owners while those with difficulties in the wage-and-salary employment market (the other tail of the ability distribution) become unincorporated business owners. Consistent with this structure, we analyze the connection between mental health and differing types of self-employment (incorporated businesses and unincorporated businesses). Psychological distress may change an individual’s tastes, i.e., degree of risk aversion, making them more attracted to establishing an incorporated business (a “pull effect”). On the other hand, if psychological distress makes maintaining wage and salary employment more difficult (a “push effect”), we expect to observe workers with psychological distress switching to unincorporated self-employment to earn a living. While psychological distress in different individuals may have different effects, we aim to examine whether there is a dominant pattern by testing the following hypotheses:

-

Push Effect: Those experiencing mental health issues (psychological distress) are more likely to become self-employed in an unincorporated business.

-

Pull Effect: Those experiencing mental health issues (psychological distress) are more likely to become self-employed in an incorporated business.

Specifically, the goal of our empirical analysis is to ascertain whether mental health problems exert an independent effect on the probability that an individual will make a particular occupational choice.

We utilize a fixed effects multinomial logit model for occupational choice. One of our empirical specification innovations is that we differentiate between self-employment in incorporated and in unincorporated businesses. Thus, we identify six primary employment classifications for individual occupational choice: (1) wage-and-salary employment only, (2) self-employed in an incorporated business,Footnote 19 (3) self-employed in an unincorporated business as a main job, (4) wage-and-salary employment with an unincorporated business as a secondary job, (5) unemployed, and (6) out of the labor force. The baseline model specification for respondent i in wave t is:

where EMPit is a categorical variable for employment category. The employment category reference group is wage-and-salary employment only. The vector MHi,t − 1 includes two lagged measures of mental health (a lagged moderate psychological distress dummy variable, and a lagged severe psychological distress dummy variable). EMPi,t − 1 controls for employment category in the previous wave.Footnote 20 Since there is a bi-directional relationship between mental health and self-employment, we exploit the time ordering of the lagged mental health measures to capture the effect of mental health on self-employment. We contend that significant coefficients on the lagged mental health measures are suggestive causal evidence of the effect of mental health on self-employment decisions.Footnote 21Footnote 22

If the sign of the mental health variable coefficient is positive (negative) and significant with regard to self-employment in an unincorporated business (incorporated business), this is suggestive that the “push effect” is the likely mechanism for the connection. If the sign of the mental health variable coefficient is positive (negative) and significant with regard to self-employment in an incorporated business (unincorporated business), then the “pull effect” is the likely mechanism for the connection.Footnote 23

Xi,t − 1 includes lagged time-varying respondent, household, and economic characteristics (indicated in Table 8) that have been found to influence employment decisions (Hvide & Panos, 2014; Astebro et al., 2011; Del Boca et al., 2000; Rees & Shah, 1986). We also include year dummy variables to control for year effects. Specifically, during our time frame, we use the year dummy variables to control for any changes in health care laws covering mental health care. A detailed description of all of the variables used and how they are constructed can be found in Appendix A. Many of these control variables could be potentially endogenous and thus bias our results. However, it is revealing to examine whether these potentially endogenous variables help to explain the significant relationships. We speculate many of these endogenous variables represent constraints that could have been induced by mental health problems. Hence for each specification, we utilize a baseline model in which only strictly exogenous controls (age and the unemployment rate) are included. Further, we perform separate regressions for men and women.

Our fixed effects multinomial logit model differences out time-invariant sources of individual heterogeneity. We argue that the coefficients estimated using the fixed effects model are more likely to capture the causal relationship from mental illness to occupational choice because unobservable time-invariant characteristics are held constant (See also Love & Smith, 2010; Bogan & Fertig, 2013). However, fixed effects would absorb the effects of any mental illness that surfaced prior to the beginning of our observation period, and hence the employment effects of long-standing mental illness would not be attributed to psychological distress in this model. As a result, we interpret the results of our fixed effects models as capturing only the effects of episodic fluctuations in psychological distress. In the robustness checks section, we conduct additional analyses to show the effects of long-standing mental illness on self-employment decisions.

Since the fixed effects model does not retain time invariant observations in which a respondent has no change in employment category during the entire sample period, the sample size is reduced.Footnote 24 The descriptive statistics for the observations used in the fixed effects models are provided in Appendix B, Table 12.Footnote 25 As a robustness check, we do analyze a specification without fixed effects and find stronger and more significant results for both men and women (See Table 14 in Appendix B). However, we do not utilize this model as our main specification because it does not allow us to control for unobservable respondent characteristics and could overstate our results.

4 Econometric analysis

4.1 K-6 score results

Table 9 presents the results for the male subgroup in the first five columns and the results for the female subgroup in the last five columns. Consistent with Hundley (2000) we find different results for men and women. For men, lagged moderate psychological distress significantly increases the probability of being self-employed in an unincorporated business as a main job (significant at the 5% level in the fully adjusted model and at the 1% level in the baseline model). For women, none of the coefficients on psychological distress are statistically significant.

Beyond indicating a link between mental health issues and self-employment decisions, these results are also suggestive of the mechanism through which mental health influences occupational choice. Given that we observe a significant connection between lagged psychological distress and unincorporated businesses, this suggests that the “push effect” is the more likely mechanism for the connection. Thus, psychological distress issues make wage-and-salary employment more difficult and make people more likely to choose self-employment in unincorporated businesses.

4.2 Robustness checks

4.2.1 Self-employment definition sensitivity

We check the sensitivity of our results to our definition of self-employment. Our data show that self-employment is concentrated within a few occupational categories (see Table 5) that generally are low barriers to entry (low fixed costs) businesses. We analyze the effect of mental health on self-employment, restricting our self-employment definition to the top self-employment categories. Table 10 shows that the results are consistent with our findings in Table 9.

4.2.2 Long-term mental health conditions

While the fixed effects model is more suggestive of a causal relationship between psychological distress and self-employment decisions, the fixed effects model only enables us to identify the effects of transitory fluctuations in psychological distress, unless the onset of a permanent mental health condition occurs during our sample period. To analyze the relationship between permanent mental health issues and self-employment decisions, we employ several long-term mental health measure model specifications.

One limitation of the K-6 measure of psychological distress is that it provides a snapshot of person’s mental health over a very short period of time. Consequently, we also try to measure the connection of the mental health history of a respondent with self-employment. In addition to the K-6 related questions, the PSID also asks whether the respondent has EVER been diagnosed with any emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems by a doctor. This question is asked in every wave beginning in 2001. We do not utilize this variable in our primary analysis as there are other drawbacks to the diagnosis question. In particular, the mental health diagnosis is a simple dichotomous variable and, because the question requires a doctor visit, captures socioeconomic status and health care preferences along with mental health status. Furthermore, the self-reports of lifetime diagnosis in the PSID survey are often inconsistent longitudinally as “individuals alter their reports to make past states consistent with current states” (Aneshensel et al., 1987).

The benefit of this question is that, after the mental health diagnosis question, respondents are asked when their mental health problems started. From these responses, we create several measures intended to capture long-term mental health issues: one dummy variable indicating if onset was before age 19, one dummy variable indicating if onset was before age 26, and one dummy variable indicating if onset was more than 10 years before the current observation of the respondent.Footnote 26 We create measures that identify the onset before age 19 and before age 26 because the literature on age-of-onset finds that half of lifetime mental disorders start by the mid-teens and three-fourths start by the mid-20s (Kessler et al., 2007). We include a measure that indicates if onset was more than 10 years before the current observation of the respondent to identify those respondents that received a diagnosis later in life. We use each of these variables in a separate regression. Using a multinomial logit model, the dependent variable in Eq. (3) is a categorical variable for employment status in the respondents’ last interview. The baseline model specification is:

where LMHi0 is one of the three long-term mental health indicators described above, and Xi1 includes all of the control variables from the first wave in which the respondent was interviewed. Again, we perform separate regressions for men and women and cluster the standards errors at the original family level. The sample in which the LMH variable indicates onset before age 26 is restricted to those over age 25; otherwise the sample is restricted to those over age 18.

Table 11, Panel A shows that for the full samples of men and women, the onset of a mental health condition before age 19 increases the probability of self-employment in an unincorporated business as a main job. The male sample results are significant at the 5% level for the baseline model. The female sample results are significant at the 1% level for the baseline and fully adjusted models.

Table 11, Panel B shows that for women, the onset of a mental health condition before age 26 also increases the probability of self-employment in an unincorporated business as a main job and an unincorporated business as a secondary job (significant at the 1% level for the baseline model and the 5% level for the fully adjusted model).

Table 11, Panel C shows a specification in which we use a measure that indicates if the onset of a mental health issue was more than 10 years before the current observation of the respondent. Panel C presents similar results to Panel B. For women, the onset of a mental health condition more than 10 years prior increases the probability of self-employment in an unincorporated business as a main job and a secondary job (significant at the 1% level). The limited number of significant results for the male subgroup could be driven by the low prevalence of mental health diagnoses for men. The National Institute of Mental Health reports that men with mental illnesses are less likely to have received mental health treatment than women in the past year.Footnote 27

5 Concluding remarks

We find a relationship between mental health and self-employment that is related to type of self-employment. Our findings, which are robust to various model specifications, suggest that episodes of moderate psychological distress can significantly increase the probability of self-employment in unincorporated businesses for men and long term mental illness can significantly increase the probability of self-employment in an unincorporated business for both men and women. Further, our results suggest that the “push effect” (some forms of mental illness may make wage-and-salary employment more difficult) is the likely mechanism for the connection between mental health issues and self-employment.

Both our measure of transitory psychological distress, which focuses on depression and anxiety, and our long term mental health condition measures, which use mental health diagnosis information, are associated with unincorporated self-employment. This does leave open the possibility that other specific types of mental health issues could be associated with incorporated self-employment. Future research would be required to identify any potential links between incorporated self-employment and mental health.

Understanding what influences the self-employment decision-making process is important for both policy makers and individuals. These results may be of importance to government agencies, such as the Small Business Administration, that support business owners with advice and planning services. Such counseling generally recognizes that individuals have differing reasons for entering self-employment and differing goals within their new venture. If individuals are embarking on self-employment ventures as a method to cope with other issues related to mental health, it is desirable to provide advice that is tailored and relevant for this audience. Just as mental health can influence how one best approaches traditional employment, it must also shape successful strategies for creating a new venture.

Additionally, it should be recognized that mental health issues may lead to a different metric for success. For example, many forms of mental illness result in frequent employment termination (some averaging as little as 10–13 weeks on the job before termination McAlpine & Warner (2002)). In this case, businesses that might not otherwise appear to be a viable alternative to traditional employment may actually be viewed as a success. More research must be conducted to determine the specific needs of business owners suffering from mental health concerns.

We have followed the prior entrepreneurship literature by interpreting unincorporated self-employment as likely reflecting constraints in the wage-and-salary market as a driver of self employment (push effect), while incorporated self-employment as reflecting preferences or opportunities for increased income (pull effect). In reality, individual preferences and constraints may be much more complicated. Individuals may prefer unincorporated self-employment to wage-and-salary employment due to flexibility or other potential beneficial aspects even if income opportunities are diminished or risky. Our work underscores the need for more detailed data allowing a careful examination of the drivers of entrepreneurial activity among those facing mental health issues.

From a socio-economic perspective, the question of how mental health problems affect occupational choices is also a salient issue that could be contributing to the income-health gradient. The large percent of Americans affected by mental illness has been a persistent issue over the past several decades (Kessler et al., 1994; National Institute of Mental Health 2017; Mojtabai et al., 2016). Since the self-employed earn less on average than wage-and-salary employees (Hamilton, 2000), holding all else constant, this evidence regarding the relationship between psychological distress and self-employment suggests that mental health issues could have long-term consequences for wealth-building for a large swath of the population. Mental health issues appear to push individuals with mental health issues into unincorporated self-employment which is associated with low earnings and has historically been unlikely to come with paid sick leave, pension plans, and health insurance. However, if the alternative for this group is unemployment, then unincorporated self-employment may be a good outcome. The Affordable Care Act could serve to further support those in unincorporated self-employment by providing better access to health insurance among the self-employed (Bailey & Dave, 2019). Nonetheless, mental health likely has important long-term consequences for the economic status of those with mental health issues.

Notes

While we follow Levine & Rubinstein (2017) in interpreting unincorporated self-employment as reflecting a poor fit with wage-and-salary labor, there is the possibility that individuals may seek self-employment for some specific benefit. Our data do not allow for any more detailed evaluation of motivation for self-employment. This suggests some care is needed in interpretation of the results that follow.

The PSID does have a high proportion of African American households, as the panel oversampled low income households from urban areas and the rural south.

Data from year 2001 is used for lagged mental health variables.

We do exclude respondent householders who are neither head, nor spouse, nor long term co-habitor, since there is no employment data for those who are not head/spouse/long term co-habitor.

We combined married and single people because a Chow test indicates that the coefficients for single individuals are not jointly statistically significantly different from those for married individuals (F = 1.14, p = 0.3256).

Within the PSID sample, who is the respondent can be correlated with who is descendant from an original PSID household and the original PSID sample focused on male respondents. This implies that the respondent householder is not entirely random. To address this concern, we analyze if couple households with the wife as a respondent are similar to couple households with the husband as a respondent in terms of basic characteristics: age, education, net worth, home ownership, financial distress, number of children, race, ethnicity, health status indicators. The differences in the health status indicator variables are not statistically significant. The differences in the other characteristic variables are statistically significant, but the actual values of the differences are small for all variables except race and net worth.

An incorporated business is a legal entity that is recognized as a person under the law. An unincorporated business is a privately owned business in which the owners have unlimited liability as the business is not legally registered as a company. Since unincorporated businesses are essentially extensions of their owners, these organizations have a finite life—each unincorporated business can only last as long as the owners live. While an unincorporated owner may be able to share business assets, (s)he is generally unable to sell his/her interest in the business because the business is legally an extension of him/herself. Additionally, unincorporated business owners must report their share of the business income and losses on their personal returns. In contrast, an incorporated business is independent and not tied to the life of any person. As a result, an incorporated business, theoretically, could last forever. Since an incorporated business is legally independent, an owner’s interest in the business can be transferred without affecting the business itself. Incorporated businesses must pay taxes on any income it earns. Then, if it distributes any income to its owners, the owners must pay tax on any cash they receive. (Source—http://info.legalzoom.com/difference-between-incorporated-unincorporated-businesses-24040.html)

Only 0.4% of the male sample and 0.2% of the female sample include respondents with wage-and-salary as a main job and incorporated business as a secondary job. Thus, these respondents are included in this category.

The PSID asks about up to four jobs where job 1 is the current or last main job and jobs 2–4 are current or past other jobs. However, we only include in the analysis jobs that the person had not left in the last two years. So, all of the jobs can be described as “current” meaning the job was held since the last wave.

Note that 0.4% of unique males were unemployed in all waves, 1.5% of unique males were OLF in all waves, 0.4% of unique females were unemployed in all waves, and 3.0% of unique females were OLF in all waves. While these figures are non-trivial, these individuals are dropped in the fixed effects model specifications so do not influence our results.

In addition to the K-6 related questions, the PSID also asks whether the respondent has EVER been diagnosed with any emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems by a doctor. This question is asked in every wave beginning in 2001. We do not utilize this variable in our primary analysis as there are drawbacks to the diagnosis question. The timing is not specific and because the question requires a doctor visit, it captures socioeconomic status and health care preferences along with mental health status. Furthermore, the self-reports of lifetime diagnosis in the PSID survey are often inconsistent longitudinally as “individuals alter their reports to make past states consistent with current states” (Aneshensel et al., 1987).

As a robustness check, we estimate a model that utilizes both a K-6 score continuous variable and a K-6 score squared continuous variable and find results consistent with our main specification.

The PSID does have a high proportion of African American households as the panel oversampled low income households from urban areas and the rural south.

Note that within our fixed effects specification, the number of biological children variable will capture the effect of having a baby on both employment decisions and psychological distress.

If consumer debt equals 0 and household income equals 0, then the financial distress variable is set to 0. If consumer debt is greater than household income, then the financial distress variable is set to 1. Approximately six percent of the sample had more debt than income. For the sample with more debt than income, the median financial distress indicator value was 1.8 with a maximum value of over 100,000. To minimize the effect of these outlier ratios, we truncated this variable at 1.

We obtain the unemployment rate data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) website.

If the respondent race observation was missing, we used the national average for the gender of the respondent. The BLS only provides unemployment rate data for four ethnic groups: Caucasian, African American, Asian, and Latino/Hispanic. For the other race group, we utilize the Asian unemployment rate.

Only 0.4% of the male sample and 0.2% of the female sample include respondents with wage-and-salary as a main job and incorporated business as a secondary job. Thus, these respondents are included in this category.

Our identification strategy includes lagged employment, similar to the Case et al. (2005) approach which also utilizes the reasoning of Granger causality to overcome similar identification challenges.

It is unlikely that current employment affects previous mental health measures. Further, our fixed effects model addresses the concern that both mental health and self-employment could have been influenced by longstanding situations.

We test for multicollinearity in our models. In all of the models, the variance inflation factor (VIF) is always below 2.83.

A less robust push-pull effect also could be identified by the relative magnitudes of the coefficient of the effect of mental distress on unincorporated business ownership and the coefficient of the effect of mental distress on incorporated business ownership. If mental distress “pushes” individuals into entrepreneurship, the unincorporated business ownership coefficient would be larger than the incorporated business ownership coefficient. If mental distress “pulls” individuals into entrepreneurship, the incorporated business ownership coefficient would be larger than the unincorporated business ownership coefficient.

Given that the identified respondent for a household can change between PSID waves, the fixed effects model also would drop households with respondent changes between waves. We did conduct analysis comparing couple households that change who is the respondent with couple households who do not change. There are only changes in respondents in 23% of the person-year observations. If the couple respondent is different than in the last wave, the couple is significantly younger on average than if the couple respondent is the same. Correspondingly, this couple household has less wealth, is less likely to be a homeowner, and is healthier on average.

The fixed effects sample size is significantly smaller but notably, those in the fixed effects sample and the full sample have similar distributions of K-6 scores. The fixed effects sample does differ from the full sample in expected ways. For example, those in the fixed effects sample are less likely to be wage-and-salary employees and more likely to have been self-employed, and they are less likely to have health insurance (which is more common with wage-and-salary employment).

These measures capture mental health conditions that are removed by our fixed effects models.

References

Andrews, G. (2001). Education and debate. BMJ, 322, 419–421

Aneshensel, C. S., Estrada, A. L., Hansell, M. J., & Clark, V. A. (1987). Social psychological aspects of reporting behavior: lifetime depressive episode reports. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 28, 232–246

Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24, 233–247

Åstebro, T., Chen, J., & Thompson, P. (2011). Stars and misfits: self-employment and labor market frictions. Management Science, 57, 1999–2017

Bailey, J., & Dave, D. (2019). The effect of the affordable care act on entrepreneurship among older adults. Eastern Economic Journal, 45, 141–159

Baron, R. A. (1999). Counterfactual thinking and venture formation: the potential effects of thinking abount ‘What might have been’. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 79–91

Bartel, A., & Taubman, P. (1986). Some economic and demographic consequences of mental illness. Journal of Labor Economics, 4, 243–256

Baumol, W. (1996). Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Business Venturing, 11, 3–22

Bedard, K., & Herman, D. A. (2008). Who goes to graduate/professional school? The importance of economic fluctuations, undergraduate field, and ability. Economics of Education Review, 27, 197–210

Blau, D. M. (1987). A time-series analysis of self-employment in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 95, 445–467

Del Boca, D., Locatelli, M., & Pasqua, S. (2000). Employment decisions of married women: evidence and explanations. Labour, 14, 35–52

Boden, R. J. (1996). Gender and self-employment selection: an empirical assessment. Journal of Socio-Economics, 25, 671–82

Boffy-Ramirez, E., Hansen, B., & Mansour, H. (2013). The effect of business cycles on educational attainment. SSRN Working Paper

Bogan, V., & Darity, W. (2008). Culture and entrepreneurship? African American and immigrant self-employment in the United States. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 1999–2019

Bogan, V. L., & Fertig, A. R. (2013). Portfolio choice and mental health. Review of Finance, 17, 955–992

Buttner, E. H. (1992). Entrepreneurial stress: is it hazardous to your health?. Journal of Managerial Issues, 4, 223–240

Cairney, J., Veldhuizen, S., Wade, T. J., Kurdyak, P., & Streiner, D. L. (2007). Evaluation of two measures of psychological distress as screeners for depression in the general population. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 111–120

Case, A., Fertig, A., & Paxson, C. (2005). The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. Journal of Health Economics, 24, 365–389

Clain, S. H. (2000). Gender differences in full-time self-employment. Journal of Economics and Business, 52, 499–513

Collins, C., Hanges, P., & Locke, E. (2004). The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: a meta-analysis. Human Performance, 17, 95–117

Cooper, A. C., Woo, C. Y., & Dunkelberg, W. C. (1988). Entrepreneurs’ perceived chances for success. Journal of Business Venturing, 3, 97–108

Cseh, A. (2008). The effects of depressive symptoms on earnings. Southern Economic Journal, 75, 383–409

Ekelund, J., Johansson, E., Jarvelin, M., & Lichtermann, D. (2005). Self-employment and risk aversion—evidence from psychological test data. Labour Economics, 12, 649–659

Engle, D., Mah, J., & Sadri, G. (1997). An empirical comparison of entrepreneurs and employees: implications for innovation. Creativity Research Journal, 10, 45–49

Ettner, S. L., Frank, R. G., & Kessler, R. C. (1997). The impact of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 51, 64–81

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). The determinants of changes in U.S. self-employment, 1968–1987. Small Business Economics, 1, 111–119

Fessler, D. M., Pillsworth, E. G., & Flamson, T. J. (2004). Angry men and disgusted women: an evolutionary approach to the influence of emotions on risk taking. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95, 107–123

Freeman, M. A., Staudenmaier, P. J., Zisser, M. R., & Andressen, L. A. (2019). The prevalence and co-occurrence of psychiatric conditions among entrepreneurs and their families. Small Business Economics, 53, 323–342

Furukawa, T., Kessler, R., Slade, T., & Andrews, G. (2003). The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of mental health and well-being. Psychological Medicine, 33, 357–362

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R., & Miranda, J. (2008). Business dynamics statistics briefing: jobs created from business startups in the United States. Technical Report, Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108, 604–631

Hessels, J., Rietveld, C. A., & van der Zwan, P. (2017). Self-employment and work-related stress: the mediating role of job control and job demand. Journal of Business Venturing, 32, 178–196

Hundley, G. (2000). Male-female earnings differences in self-employment: the effects of marriage, children, and the household division of labor. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 54, 95–114

Hvide, H. K., & Panos, G. A. (2014). Risk tolerance and entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 111, 200–223

Jamal, M. (1997). Job stress, satisfaction, and mental health: an empirical examination of self-employed and non-self-employed Canadians. Journal of Small Business Management, 35, 48–57

Kawamura, K. Y., Hunt, S. L., Frost, R. O., & DiBartolo, P. M. (2001). Perfectionism, anxiety, and depression: are the relationships independent?. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 291–301

Kessler, R. C., et al. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8–19

Kessler, R. C., et al. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 184–189

Kessler, R. C., et al. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20, 359–364

Kihlstrom, R. E., & Laffont, J.-J. (1979). A general equilibrium entrepreneurial theory of firm formation based on risk aversion. Journal of Political Economy, 87, 719–748

Kirchler, E., Hoelzl, E., & Kamleitner, B. (2008). Spending and credit use in the private household. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 519–532

Knight, F. H. (1965). Risk, uncertainty and profit. New York: Harper and Row

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more?. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132, 963–1018

Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267–286

Love, D. A., & Smith, P. A. (2010). Does health affect portfolio choice?. Health Economics, 19, 1441–1460

Lundberg, S., Startz, R., & Stillman, S. (2003). The retirement-consumption puzzle: a marital bargaining approach. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1199–1218

Maner, J. K., et al. (2007). Dispositional anxiety and risk-avoidant decision-making. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 665–675

McAlpine, D. D., & Warner, L. (2002). Barriers to employment among persons with mental illness: a review of the literature. Technical Report, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University

Min, P. G. (1988). Korean immigrant entrepreneurship: a multivariate analysis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 10, 197–212

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., & Han, B. (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics, 138, 1–10

National Institute of Mental Health. (2017). Mental illness. Retreived August 2, 2018, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (2013). What are the symptoms of bipolar disorder? Retreived January 15, 2013, from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/

National Institute of Mental Health. (2013). What are the symptoms of depression? Retreived January 15, 2013

Pendergast, W. R. (2003). Entrepreneurial contexts and traits of entrepreneurs. Proceedings of the Teaching Entrepreneurship to Engineering Students—Engineering Conferences International

Prochaska, J. J., Sund, H.-Y., Max, W., Shi, Y., & Ong, M. (2012). Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21, 88–97

Rees, H., & Shah, A. (1986). An empirical analysis of self-employment in the U.K. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 1, 95–108

Rietveld, C. A., van Kippersluis, H., & Thurik, R. (2015). Self-employment and health: barriers or benefits?. Health Economics, 24, 1302–1313

Small Business Association Office of Advocacy. (2012). Do economic or industry factors affect business survival?. Technical Report, Small Business Association Office of Advocacy

Smith-Hunter, A., Kapp, J., & Yonkers, V. (2003). A psychological model of entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics, 2, 180–192

Stephan, U., & Roesler, U. (2010). Health of entrepreneurs versus employees in a national representative sample. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 717–738

Tremblay, C. H., Grosskopf, S., & Yang, K. (2010). Brainstorm: occupational choice, bipolar illness and creativity. Economics and Human Biology, 8, 233–241

van Praag, C., & Cramer, J. (2001). The roots of entrepreneurship and labour demand: individual ability and low risk aversion. Economica, 68, 45–62.

Zivin, K., Paczkowski, M., & Galea, S. (2011). Economic downturns and population mental health: research findings, gaps, challenges, and priorities. Psychological Medicine, 41, 1343–1348

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Cawley, Janet Currie, Angus Deaton, David Bradford, and seminar participants at Cornell University, Duke University, Princeton University, and the University of Georgia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

1.1 A. Description of variables used in primary analysis

1.1.1 Employment variables

-

Employment Status Unordered Categorical Variable (six categories): Each respondent is asked about up to four jobs where job 1 is the current or last main job and jobs 2-4 are current or past other jobs. For this variable, we only include in the analysis jobs that the person has not left in the last two years. Thus, all of the jobs can be described as "current" meaning the job was held since the last wave. For each job, they are asked whether this job involves being self-employed or employed by someone else. If they respond that they are self-employed, then they are asked if that is an unincorporated business or a corporation. From these three questions, we categorize each head and spouse as one of the following: (1) wage-and-salary employment only, (2) wage-and-salary employment with an unincorporated business as a secondary job, (3) main job is self-employment in an unincorporated business, (4) is self-employed in an incorporated business, (5) unemployed, or (6) out of the labor force. Note that only 0.4% of the male sample and 0.2% of the female sample include respondents with wage-and-salary as a main job and incorporated business as a secondary job. Thus, both respondents with an incorporated business as a main job and respondents with an incorporated business as a secondary job are included in one category.

1.1.2 Mental health variables

-

Moderate Psychological Distress Dummy Variable (lagged one wave)—The respondent is asked a series of 6 questions about their current feelings. The questions ask the respondent to rate the following feelings on a scale of 0 (=none of the time) to 4 (=all of the time): whether he/she has felt sad, nervous, restless, hopeless, worthless, and that everything was an effort in the last 30 days. These question responses are summed to create the K-6 non-specific psychological distress score. If the K-6 score is between 5 and 12 (inclusive) this variable is given a value of 1 and is set to 0 otherwise.

-

High Psychological Distress Dummy Variable (lagged one wave)—The respondent is asked a series of 6 questions about their current feelings. The questions ask the respondent to rate the following feelings on a scale of 0 (=none of the time) to 4 (=all of the time): whether he/she has felt sad, nervous, restless, hopeless, worthless, and that everything was an effort in the last 30 days. These question responses are summed to create the K-6 non-specific psychological distress score. If the K-6 score is higher than 12 this variable is given a value of 1 and is set to 0 otherwise.

-

Mental Health Diagnosis Dummy Variable—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual has been told by a doctor that he/she has or had any emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems and is set to 0 otherwise.

1.1.3 Demographic characteristic variables

-

Age Variable—The age in years of the individual.

-

African American Dummy Variable—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual is African American and is set to 0 otherwise.

-

Hispanic Dummy Variable—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual is Hispanic and is set to 0 otherwise.

-

Other Race Dummy Variable—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual is not Caucasian, African American, or Hispanic, and is set to 0 otherwise.

-

Married Dummy Variable—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual is married and is set to 0 otherwise.

-

Number of Children Variable—A variable indicating the number of children under the age of 18 currently in the household.

1.1.4 Socio-economic status variables

-

No High School Diploma—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual reports that their completed years of education is less than 12, and is set to 0 if otherwise.

-

Some College—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual reports that their completed years of education is greater than 12 and less than 16, and is set to 0 if otherwise.

-

College Graduate—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the individual reports that their completed years of education is greater than 16, and is set to 0 if otherwise.

-

Log of Household Net Worth—The natural logarithm of the combined value of stock holdings, savings accounts, checking accounts, government bonds, T-bills, a valuable collection, bond funds, rights in a trust or estate, holdings in a farm or business, real estate other than the main home, and assets in IRA accounts, Keogh accounts, 401Ks or similar defined contribution pension plans, net of the value of debt from credit cards charges, student loans, medical or legal bills, or loans to relatives. It also includes main home and second home equity and the net value of vehicles. All dollar values are adjusted to 2017 US$ using the all-item CPI-U from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.)

-

Own Home (Primary Residence) Dummy Variable—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the respondent owns or is buying a home and is set to 0 otherwise.

-

Financial Distress Indicator—The value of household consumer debt (Household consumer debt includes credit card charges, student loans, medical or legal bills, or loans from relatives but does NOT include any mortgage on a primary residence or vehicle loans.) divided by household income, \(\frac{\,{{\mbox{consumer debt}}}}{{{\mbox{household income}}}\,}\). The scale goes from 0 to 1 where 1 is distressed. Approximately six percent of the sample had more debt than income. For the sample with more debt than income, the median financial distress indicator value was 1.8 with a maximum value of over 100,000. To minimize the effect of these outlier ratios, we truncated values at 1.

1.1.5 Physical health-related variables

-

Number of Chronic Conditions Variable—A variable that counts the number of chronic conditions that a doctor has ever told them they had from the following list of possible conditions: high blood pressure or hypertension; diabetes or high blood sugar; cancer or a malignant tumor (excluding skin cancer); chronic lung disease such as bronchitis or emphysema; coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure; or arthritis or rheumatism. This variable ranges between 0 and 6. This variable is recorded separately for the husband and wife in couple households.

-

Total Medical Expenditures Variable—A variable that sums together all out-of-pocket expenditures for health insurance premiums; nursing home or hospital care; doctor, outpatient surgery, or dental care; and prescriptions, in-home medical care, special facilities, or other services for any member of the household. (All dollar values are adjusted to 2017 US$ using the all-item CPI-U from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.)

-

Has Health Insurance Variable—A dummy variable that is given a value of 1 if the respondent was covered by health insurance for the full prior year, and 0 otherwise.

1.1.6 Other control variables

-

Year Dummy Variables—Dummy variables for years 2001, 2003, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, and 2015.

-

Unemployment Rate Variable—A continuous variable indicating the national unemployment rate specific for each individual’s race (white, African-American, Hispanic, and Asian=Other) and gender, and the interview year. Values ranged from 3.1 to 17.8.

B. Fixed effects sample descriptive statistics

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bogan, V.L., Fertig, A.R. & Just, D.R. Self-employment and mental health. Rev Econ Household 20, 855–886 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-021-09578-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-021-09578-3