Abstract

This research uses nationally representative data to study how economic resources and inequalities are associated with life satisfaction of Chinese residents. We construct economic resource and inequality measures from expenditure rather than from income, after confirming that expenditure inequality is a better measure in the Chinese context. We find that economic inequalities in general are negatively associated with life satisfaction, and that this association is larger for inequalities in the lower half of the distribution than those in the upper half of the distribution. We further explore the mechanisms under which inequality can be associated with life satisfaction, and find that aspiration is potentially one important channel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While China has achieved remarkable economic growth over the past 30 years and surpassed Japan to become the second largest economy in the world in 2010, a variety of related phenomena could increase social discontent within China. These issues include corruption, deterioration of the environment, and rising economic inequality. Inequality may be especially of concern as China has become the Asian country with the highest level of income inequality (Asian Development Bank 2007). Moreover, China’s income-based Gini coefficient increased from 0.33 in 1980 to 0.46 in 2000 (Chang 2002), and then to 0.49 in 2007 (Xie and Zhou 2014). Although it has stopped increasing in recent years, the Gini coefficient in China is still among the highest around the world. There is intense scholarly and policy debate about whether economic growth when accompanied by rising economic inequality leads to improvements in subjective well-being (SWB) of their residents. How China’s economic growth and the accompanying rising inequalities affect subjective well-being is an empirical question that needs further investigation.

The relationship between income inequality and subjective well-being is mixed both from a theoretical perspective and across empirical studies. Due to diminishing marginal utility of income, Lerner (1944) argues that increases in inequality will in general decrease welfare of society, implying a negative relationship between increases in income inequality and subjective well-being. In contrast, Hirschman and Rothschild (1973) describe the “tunnel effect” of an initial increase in inequality, i.e., individuals may perceive increased economic inequality as signaling better economic opportunities for themselves.

Empirical studies on the association of income inequality with subjective well-being find mixed effects. Senik (2004) uses the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey data from 1994 to 2000 to explore the relation between life satisfaction and income distribution, and finds evidence supporting the “tunnel effect” conjecture. Grosfeld and Senek (2010) show that in the economic transition period of Poland, income inequality at first contributes positively to people’s happiness from 1992 to 1996, but the relation reverses in the period after 1997. Luttmer (2005) using American data finds that higher income of neighbors is negatively correlated to one’s happiness, after controlling for one’s own income.

Angus Deaton and his coauthors enriched the literature on subjective well-being from several perspectives. Deaton (2008) uses Gallup World Poll data on national samples of adults from 132 countries to explore life satisfaction’s relationships with national income, age, and life-expectancy. He finds that per capita national income strongly positively affects life satisfaction and that the relationship is almost linear in the log formulation. Kahneman and Deaton (2010) further distinguished subjective well-being into two aspects: emotional well-being or happiness, and life evaluation or life satisfaction. They find that income and education are more important determinants of life evaluation, but health, care giving, loneliness and smoking are more closely related to daily emotions. High income increases life satisfaction but not happiness, and low income is associated both with low life evaluation and low emotional well-being. In addition to studying subjective well-being for the population in normal times, Deaton (2012) examined the 2008 Financial Crisis impacts on the emotional and evaluative lives of the population. He finds that both emotional well-being and life evaluation declined sharply during the fall of 2008 and spring of 2009, but largely recovered by the end of 2010. Deaton and Stone (2013) further show that relative income may not be a critical factor for subjective well-being.

There are also studies on the relationship between inequality and SWB in developing countries, including China. Among them, Appleton and Song (2008) use the China Household Income Project (CHIP) 2002 data to report that in urban China life satisfaction is positively correlated with individual attributes such as self-reported good health status, being married, and female. But in terms of income inequality, they find that relative income does not significantly affect life satisfaction. Knight et al. (2009) use the 2002 sample of CHIP data to study life satisfaction in rural China. They report a positive effect of inequality on happiness, but a negative effect of others’ income within the village. Chen and Zhang (2009) review the literature on inequality and income distribution in rural China, and on its determinants and relationship with households.

They also identify new research areas with existing panel datasets, and a new panel dataset to shape future research. Knight and Gunatilaka (2010b) study subjective well-being functions for urban and rural China. They report that although urban households are richer than rural households, rural households have higher subjective well-being than their richer urban counterparts. Oshio et al. (2011) examined the relative income effects on happiness by using data from China, Japan and Korea. Consistent with previous literature, their paper also finds a significantly positive association of individual’s relative income and perceived happiness. In contrast to Japan and Korea, Chinese residents’ happiness has stronger associations with relative income calculated by individual income than by family income. Easterlin et al. (2012) use data from six surveys to document the relationship of life satisfaction and income inequality between 1990 and 2010 in China. They find a U-shape age relation in life satisfaction similar to those observed in developed countries. They also report that rapid economic growth in this period benefited higher-income and better-educated groups with higher life satisfaction, but led to declining life satisfaction in the lower-income group.

In recent years, more studies have paid attention on the mechanisms behind the impacts of inequality on SWB. Knight and Gunatilaka (2010a) provide one reason why China’s rural-urban migrant households report lower happiness than rural households. They find that certain features of migrant conditions and high aspirations in relation to achievement produce unhappiness. Frijters et al. (2012) explored the relationship between optimistic income expectations on life satisfaction using 2002 household survey data. They show that expectations have strong associations with life satisfaction especially for urban areas, but countryside residents and rural-to-urban migrants have higher levels of optimism about the future. Jiang et al. (2012) distinguish between different effects of between-group and general inequality on happiness. Their paper indicates that people feel unhappy with between-group inequality, but that general inequality is positively related to happiness after controlling for identity-related inequality and other characteristics. Asadullah et al. (2015) find that women, urban residents and people with higher income are happier in China. Rich people care more about relative income, whereas poorer residents pay more attention to absolute income.

Our paper adds to the existing literature in the following ways. First, we measure inequalities in economic resources using both income and expenditure data and focus on expenditure inequality, as consumption expenditure is a more comprehensive and accurate measure of economic resources in developing countries (Strauss and Thomas 2008). We study the relationships of consumption expenditure levels and of consumption expenditure inequality with life satisfaction and compare the findings with those obtained from using income measures. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to compare the impacts of inequality on life satisfaction measured by both expenditure and income using micro dataset from China.

Second, this paper provides a comprehensive view of how inequalities are associated with life satisfaction in both urban and rural China using the national representative China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data. While Easterlin et al. (2012) provide evidence that poorer individuals dislike inequality more, whether being poor in rural areas is worse than being poor in urban China is not directly addressed. Indeed, Knight et al. (2009) observed that rural-dwellers in China appear to be relatively happy despite their poverty and low socioeconomic status. In this paper we will take advantage of the size of the CFPS data and sample to study within and between measurements of inequality on well-being of rural and urban residents.

Third, we further separate urban residents into those with and without urban Hukou, and study their life satisfaction. Knight and Gunatilaka (2010a) explore why China’s rural-urban migrant households report lower happiness than rural households and find that high aspirations in relation to achievement produce unhappiness, but they don’t focus on the heterogeneous impacts of inequality on subgroup’s life satisfaction within urban residents. In this paper we define people who live in urban areas but have rural Hukou as migrants. Hukou (household registration system) is still one of the most important factors associated with each individual’s rights and welfare in China. Migrants without urban Hukou do not have equal rights in employment, pension system, medical care, children’s education permission, and so on. As a result, migrants might have different feelings about inequality, or different valuation of their subjective life satisfaction.

Finally, this paper also explores the mechanism behind the basic relationship between inequality and life satisfaction. The literature has pointed out that individual’s subjective welfare is determined not only by the actual level of material life, but also by his/her aspiration (Veenhoven 1995; Inglehart 1990; Knight and Gunatilaka 2010a). However, the current literature doesn’t test aspiration as a potential channel of inequality’s effect on life satisfaction. CFPS data enable us to employ a measure of aspiration and to investigate its role in associating inequality with life satisfaction.

The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 briefly describes the CFPS data and the variables to be used in our analysis. It also defines and shows the relationship between life satisfaction and our two measures of economic status—per capita income and per capita consumption expenditures. Section 3 describes the estimation models and defines the other explanatory variables to be used in our regression analysis. Section 4 presents the main results of the empirical models. Finally, section 5 highlights our main conclusions.

2 The CFPS data and major variables

2.1 CFPS data

In this research, we use the 2012 wave of China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) national representative data to disentangle relationships between economic inequalities and life satisfaction. CFPS is a biennial survey conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey at Peking University. The first wave was implemented in 2010, and a follow-up investigation was conducted in 2012. CFPS collects data at three different levels: the community, household, and individual level. The adult questionnaire collects information about demographics, socio-economic conditions, subjective well-being, and health of those 16 and over. The household questionnaire collects the information about household income and expenditure.

To ensure national representativeness, CFPS divides the national Chinese population into six sampling frames employing a multi-stage stratification with probability proportional to size sampling strategy. At the first stage, 144 county-level units were randomly selected; 640 village-level units (villages in rural areas and urban communities in urban areas) were then randomly chosen from these counties in the second stage; and finally at the third stage, over 10,000 households were selected in these areas.

The CFPS baseline covers 25 provincesFootnote 1 and about 95% of the Chinese population. In this study, we focus on the national representative sample of CFPS 2012 with no missing reports of life satisfaction, which contains 7940 households and 19,583 adults from these households. All families in each selected household are then sampled, and all members within each family are interviewed. Individuals are selected using the following standard: family members who live together and who are directly related due to genetics, marriage, adoption or fostering; or non-family members living together for more than 3 months who share economic resources as a unit.

CFPS 2012 is the follow-up of CFPS 2010, but with significant revisions in the measurement of both household income and expenditure due to difficulties encountered in the 2010 wave. For example, home-produced and home-consumed agricultural products were not included in the expenditure and income concepts in the 2010 wave but were included in the 2012 wave. In addition, in 2010 public transfers were asked in a single item about the amounts which lead to a significant understatement of public transfers. In contrast, in 2012 public-transfer income information was collected using a more detailed set of questions on specific types of public transfers. Finally, the value of work-related fringe benefits is collected in 2012 but not in 2010. Because of these measurement problems, we use the 2012 wave to measure household per capita income and household per capita expenditure, the central concepts in our research.

2.2 Measuring subjective well-being

We focus in this paper on answers to the satisfaction with life questions to evaluate subjective well-being of Chinese residents (Frey and Stutzer 2000). In the adult questionnaire, the life-satisfaction variable records the degree of life satisfaction of the respondent, where she/he is asked to choose a number from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied) for the question “How satisfied are you with your life?” Life satisfaction is an evaluative measure tapping into people’s thoughts and feelings about their life as a whole while the happiness measure of SWB is believed to be a hedonic measure emphasizing feelings and events at the moment (Stone et al. 2010). While the concepts are related, the literature indicates that they often have different correlates and the same may be true in China (Kahneman and Deaton 2010).

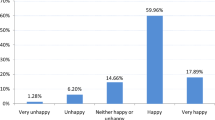

Figure 1 provides the distribution of self-reported life satisfaction for the whole CFPS sample. If we group individuals choosing 4 or 5 as being satisfied with their life, and those who choose 2 or 1 as those who are dissatisfied, Fig. 1 indicates that 40.6% of total respondents report themselves satisfied with life. At the other part of the distribution, 17.4% of Chinese residents report themselves unsatisfied with their lives. Life satisfaction of urban residents in general is higher than that of the rural residents (with mean value of life satisfaction to be 1.25 vs. 1.21, Table 1).

Since the urban-rural division is a prominent feature of life in China, in Table 2 we tabulate life satisfaction distributions for rural and urban residents respectively, based on their current place of residence and their household registration (Hukou) status for those who live in urban areas. There are relatively few people with urban Hukou living in rural areas. On average, urban residents appear to be somewhat more satisfied with their lives than rural residents, reflecting mainly by the 4th category of ‘satisfied’. Within urban areas, those with urban Hukou status appear to be more satisfied than those with rural Hukou status, but the gap is not very large.

2.3 Measuring economic resources

Two principal measures of household economic resources are available in the CFPS survey—income and consumption expenditures. While household income is the conventional aggregate measure in developed countries, household expenditure is collected in CFPS since the literature has shown that expenditure can be a much better welfare measure than income in developing countries (Strauss and Thomas 2008). First, consumption expenditure is believed to suffer much less from measurement error than income measures in survey data for developing countries. Second, the life-cycle theory implies that as agents smooth inter-temporal consumption, expenditure is influenced less by idiosyncratic shocks than income. Third, as conspicuous consumptions and gift-giving expenditure reflect more of one’s social status in China especially in rural areas (Chen and Zhang 2012; Chen 2015), studying the relationship between expenditure inequality and life satisfaction is of more practical importance.

To minimize recall bias, household expenditures in CFPS are collected either at weekly, monthly, or yearly frequencies. Weekly-based expenditures are about food consumption, liquor, and cigarettes, while monthly-based expenditures are those usually spent each month, including communication, water, electricity, fuel, employing nanny, local transportation, daily goods, entertainment, lottery, and house rent. Yearly-based items record expenditures occurred occasionally in a year, and include housing-related expenditure, household appliance/service expenditure, clothing, travelling, medical care expenditure, education expenditure, etc. Household expenditure per capita is then constructed by dividing total annual consumption expenditure by the number of household members.

Household income is calculated by adding up household-level income and individual-level income from all sources. Household income includes net agriculture income, self-employed activity income, public transfer income, asset income, and private transfer income. Individual level income includes wage income, self-employment income, and public-transfer income specific to individuals. We then divide total household income by the number of household members to get per capita values.

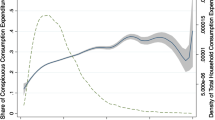

Table 3 displays differences between expenditure and income measures of economic resources. In this table, we show the distribution of household income per capita and household expenditure per capita at relevant percentiles in the respective distributions. Whether we use incomes or expenditures, median values of each metric are about the same. At the top of the distribution, incomes actually somewhat exceed expenditures, a reflection of the well-documented savings behavior of well-off Chinese households. The real problem with the income measure is concentrated at the bottom end of the distribution where expenditures are well in excess of incomes. This is clearly the part of the distribution where incomes are frequently not monetized and are poor measures of economic resources.

Table 3 demonstrates that the principal source of differences in economic inequality in the income and expenditure measures lies at the bottom end of the distribution. To illustrate, median income is 19 times income at the 5th percentile (P50/P05 of income) while the comparable number for expenditure is only about 3.9 (P50/P05 of expenditure). In sharp contrast, income at the 95th percentile is 4.7 times median income (P95/P50 of income) while the comparable ratio for expenditure is 4.1 (P95/P50 of expenditure).

Another perspective on differences between these two measures of household economic resources is contained in Table 4, which lists mean levels of logarithm of per capita income (log PCI) and logarithm of per capita expenditure (log PCE) based on deciles of household per capita income. Table 4 also presents the information by urban (Panel A) and rural (Panel B) residents. The most noticeable pattern in Table 4 is that the variation in log PCE is smaller than that of log PCI for the lower half of the income distribution both for the urban and rural residents. To illustrate with the urban sample, the log PCI in the first decile is only 60.9% of the median income (5.58/9.17), while the corresponding ratio for log PCE is 96.8% (8.75/9.04). This illustrates that households at the bottom of income distribution consume well above their income, providing evidences that expenditure measure is more smooth and is more likely to reflect permanent income. Income is just not a good measure of total economic resources at the bottom of the income distribution which is why expenditures are so high relative to income at the bottom of the income distribution.

The data in Tables 3 and 4 also suggest that the relationship of economic inequality measures to satisfaction may be sensitive to the inequality measures used and the degree to which these alternative measures emphasize the bottom or the top half of the distribution. Because of this we will use four alternative measures of inequality in our models for both expenditure and income per capita—Gini coefficients, P90/P10, P90/P50, and P50/P10.

3 The estimation models

We use ordered probit to model life satisfaction, where life satisfaction is redefined into three categories, combining those reporting 1 and 2 into the first category, 3 as a separate category, and 4 and 5 into another category.Footnote 2 We further estimate separate models for the full sample, for urban and rural residents separately. For urban residents we estimate in addition separate models for those with rural Hukou and urban Hukou status.

In addition to economic resources measured by log PCE and log PCI, we also use supplemental measures of the relative expenditure or income at the county level, as life satisfaction may be influenced also by the economic conditions of their neighbors. We calculate the relative expenditure/income using the average county-level expenditure/income excluding the respondent’s own household per capita expenditure/income in computing these county averages. This formulation may also help capture any reference group effects (e.g., Clark 2003).

The second set of economic explanatory variables relates to our inequality measures. We construct inequality measures at the county level for two reasons. First, county is the administrative level that persistently exists in Chinese history regardless of changes of dynasties. Chinese people have a strong sense of belonging to a county, making inequality comparison at this level meaningful. The second reason is to maintain sufficient individual variation within the geographic unit chosen, which county-level measures do. In our paper’s sample, the number of counties is 104 in total.

Four alternative measures of inequality are used. The first is the widely used Gini coefficient. The second is the expenditure/income at the top 10% divided by those at the bottom 10% decile (P90/P10) in a county. The third and fourth measure divide inequality into the top half and bottom half of the distribution, by using the top 10% over the median (P90/P50) in a county, and the median over the bottom 10% (P50/P10) in this county.

We use three additional variables (poverty ratio, access to tap water and to electricity) to control for a potential co-founding associations due to other county-level economic resources. Among them, the poverty ratio is the share of population under poverty line, which can help to disentangle the effect of absolute povertyFootnote 3; access to tap water and electricity allows us to control living facility conditions at the county level.

Two sets of models are estimated, with the first set using log PCE and the second using log PCI as the economic resource measure. In each of the two models five sets of estimations are presented with various inequality measures: the Gini coefficient, P90/P10, and the combination of P90/P50 with P50/P10. The third set of models estimates life satisfaction by using expenditure for different subsamples, first separating urban and rural residents, and then further dividing urban residents into those with and without urban Hukou.

A set of individual characteristics are also controlled. Among them, we include a variable indicating how confident one is about his/her future, measured using a 1 to 5 scale. Another variable is how the respondent views his/her own social status. Both of these are measured using a 1 to 5 scale with higher numbers indicating more confident or higher social status. We define people who choose 4 or 5 as confident or high status.

Other control variables include age (using a quadratic in age), gender (a dummy variable for male), marital status (a dummy variable for currently married or cohabitating), education categories (primary school, high school and college, with no education as the omitted group), health status (a dummy for those who choose 1 (extremely healthy) or 2 (very healthy) for their self-reported health), whether a communist party member, and regional dummies (dummy variables for East, and Middle with the West region the omitted group). Table 1 provides summary statistics for the full sample, the urban and rural sample separately and finally for urban residents with urban and rural Hukou status separately.

4 Empirical results

In this section we present the empirical findings, with Table 5 and Table 6 estimating the associations of expenditure and income measures with life satisfaction respectively. Table 7 presents estimation results of expenditure measure for different subsamples.Footnote 4 Based on these tables we first discuss the association of life satisfaction with inequalities, measured by Gini coefficients, P90/P10, P90/P50, and P50/P10. We then discuss how life satisfaction is associated with economic resources in terms of the household level log PCE and PCI and the county-level relative measures. We then report how other non-economic characteristics correlate with life satisfaction. We finally explore how inequality may be associated with life satisfaction through channel of changing individual aspirations in Table 8.

4.1 Inequality and life satisfaction

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, there are large differences in estimated associations in the full sample depending on whether we use an income-based or expenditure-based measure of inequality. Expenditure inequalities are negatively associated with life satisfaction; in contrast the coefficients of income inequality are inconsistent across different measures of economic inequality, positive for some measures and negative for other measures. Secondly in terms of statistical significance, the negative associations for expenditure inequality are significant in all measures except for P90/P50 while those for income inequality are again not stable. Thirdly in terms of coefficient magnitudes, expenditure inequality coefficients are much larger, with those for income inequality being close to zero. We focus on an expenditure inequality measure in later analysis as expenditure as expected appears to be more reliable in terms of describing the association of inequality in economic resources with life satisfaction.

Column 3 in Table 5 shows that expenditure inequality at the bottom half of the distribution (P50/P10) has larger negative coefficients than that at the top half of the distribution (P90/P50). In other words, our regressions indicate that life satisfaction of Chinese residents is more sensitive to inequalities at the bottom of distribution than those at the top.

If inequality at the bottom gets larger, it suggests that a larger proportion of individuals are worsening their living standards from poor to very poor. For those who are not at the bottom, larger inequality due to larger changes at the bottom may indicate their living standards in communities are deteriorating with worse neighborhoods with a less clean and less safe living environment due to such changes.

On the other hand, if inequality at the top gets larger, it means the rich get richer. For those above the median, such changes may create smaller associations, not only because they still maintain a relatively decent life, but also due to a possible “tunnel effect,” that is, they themselves may have a chance to obtain more economic resources in the future. This will lessen negative associations of inequality with SWB. For those at the bottom, the top individuals are not their comparison group anyway so that larger inequality due to rich get richer may bother them less.

As shown in Table 7, the coefficients of expenditure inequality are negatively significant for urban residents but not so for their rural counterparts (columns 1 and 2). When we focus on urban residents with and without urban Hukou (columns 3 and 4), we find that coefficient for inequality is smaller for migrants, i.e., urban residents without urban Hukou. This implies that although migrant workers work and live in urban areas, they may not fully enjoy the benefits associate with urban Hukou. Even though we find that the impact of Gini on life satisfaction is different in subsample regressions, the formal tests discussed in the bottom of Table 7 show that all the differences between geographic subsamples are statistically insignificant.

4.2 Economic resources and life satisfaction

Table 5 shows that higher household per capita expenditure is associated with greater levels of life satisfaction, while Table 6 provides similar findings for the income per capita measure. In Table 7, the estimated coefficients of log PCE for urban residents is more than five times that for their rural counterparts. We also note that the coefficient for urban resident with urban Hukou is larger than those with rural Hukou. One possible explanation is that the availability of higher quality and better variety of goods (good restaurants, shopping malls, sporting events, etc.) to consume is much larger in urban areas than in rural places so that greater economic resources more easily translate into higher life satisfaction in urban places.

In China, many public resources are tied with household registration (Hukou) status. For example, the child of a migrant to urban areas may not be eligible for nearby schools because his/her parents have rural Hukou status. Similarly, access to medical care and its better quality may not improve for those with rural Hukou in urban areas. Increases in economic resources of rural Hukou people living in urban areas do not directly suspend or mitigate Hukou rules under which they are governed thereby limiting potential improvements in their SWB. Not surprisingly then, increases in household expenditures have much smaller effects on SWB for those urban residents with rural Hukou status compared to those with urban Hukou status.

We next consider how relative economic resources of neighbors are associated with life satisfaction. Luttmer (2005) find that neighbor’s income is negatively associated with one’s happiness in the U.S. context. Our finding is that for China, after we control for inequality measures and level of own economic resources, the relative measure appears to be insignificant for log PCE. For income, the coefficients are positive and significant, which is counter-intuitive, providing another piece of evidence that income inequality may not be appropriate when studying the relationship between inequalities and life satisfaction in countries such as China.

The insignificance of relative expenditure may not be that surprising. On the one hand, the Chinese are a migratory population so that many of them have lived in many different types of communities over their lifetimes (Zhao 2002). An evaluative SWB outcome such as life satisfaction may not be only connected to current community economic resources alone. On the other hand, given the rapid economic growth that has taken place in China over the last few decades, current resources of the community may not capture well lifetime community-level economic resources even for non-migrants. We find very similar results for the relative economic variable when the data are stratified by urban-rural places and by Hukou status in Table 7. Life satisfaction is unrelated to any measure of relative expenditure in all the subsamples.

In order to rule out associations of absolute poverty and other living facilities, we add county-level poverty ratio and whether access to tap water and electricity into the regression. We find that poverty ratio has insignificant associations with satisfaction, but access to tap water and stable electricity both have significantly positive associations with life satisfaction.

4.3 Non-economic resources and life satisfaction

The coefficients on the non-economic variables are generally consistent with the existing literature and are not sensitive to different model specifications; hence we report them in Tables 5 and 6 and omit them in later tables. To illustrate, those who are confident about the future and believe themselves to be of high social status report themselves as more satisfied with their lives. Urban Hukou residents in urban areas who report themselves ‘high status’ are more likely to report that they are satisfied with their lives.

The associations of other personal traits are similar to those documented in the literature. For example, in China in both urban and rural places, age has a U-shape association with life satisfaction, gradually decreasing, bottoming in the 40’s and reaching its highest levels in old age (similar to Blanchflower and Oswald 2004; Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Gowdy 2007; Lei et al. 2015). Men have lower levels of satisfaction than women do in all types of places while being married or cohabiting significantly improves life satisfaction. Being in good health has positive and significant effect on life satisfaction, consistent with the literature (e.g., Appleton and Song 2008; Knight et al. 2009).

We also find that more education has little association with self-reported life satisfaction. If we re-estimate the model dropping the economic resource and social status variables (log PCE, relative expenditure, etc.), the coefficient for education will be significant, indicating that education is highly associated with economic resources and social status.Footnote 5

4.4 Expenditure inequality and aspirations

In this subsection, we will explore some possible mechanisms behind the negative association of expenditure inequality and life satisfaction. The theory of aspiration indicates that individual’s subjective welfare is determined not only by the actual level of material life, but also by his/her aspirations (Veenhoven 1995; Inglehart 1990; Knight and Gunatilaka 2010b). Based on this theory, perception of income status equals the ratio of actual income status over aspirations; thus one can measure aspirations as the ratio of actual income status over perceptions of one’s income status.

CFPS asks respondents to report their perceptions of income ranking in his/her local area using a 1 to 5 scale, with higher numbers indicating higher ranking. As we know each respondent’s actual income, we can construct the aspirations measure accordingly. We therefore construct aspirations by dividing respondents within the same county into 10 groups by their actual income. We then divide this value with the reported ranking of their income perceptions. The higher this aspirations measure, the inferior one feels about his/her relative social status in terms of income.

Table 8 shows the results of expenditure inequality’s effect on one’s aspirations. We find that all of the inequality variables have significantly positive associations with aspirations, especially inequality within the bottom part (expenditure P50/P10). This potential mechanism indicates that when inequality becomes larger, people’s aspirations are increasing and people are less satisfied with their life.

5 Conclusion

In this paper we use CFPS nationally representative data to study how economic resources and inequalities are associated with subjective well-being of Chinese residents. The relationships of consumption expenditure levels and of consumption expenditure inequality with life satisfaction are studied and the findings are compared with those obtained from using income measures.

We have the following four findings. First, economic inequalities in general are negatively associated with life satisfaction, after controlling for household absolute and relative levels of economic resources and other personal characteristics. Moreover, life satisfaction of Chinese residents is more sensitive to inequalities of the lower half of the distribution than those of the upper half of the distribution. Second, greater economic resources at the household level improve life satisfaction and do so more so in urban areas compared to rural places. Third, economic resources of neighbors in the same county measured by relative expenditure appear to have little effect on life satisfaction. Fourth, our exploration on the mechanism indicates that inequality may be associated with life satisfaction through changing one’s aspirations.

Notes

Tibet, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Hainan, Hong Kong, and Macao were not included.

Our results are robust to alternative formulations of the dependent variables and different empirical strategies.

We thank an anonymous referee for this suggestion.

To save space we present subsample estimation results for Gini coefficients only. Estimations using other inequality measures are similar and are available upon request.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this estimation, and the results are available upon request.

References

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in urban China: Components and determinants. World Development, 36(11), 2325–2340.

Asadullah, M. N., Xiao, S., & Yeoh, E. (2015). Subjective well-being in China, 2005–2010: The role of relative income, gender, and location. China Economic Review, in press, available online at doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2015.12.010.

Asian Development Bank. (2007). Reducing inequalities in China requires inclusive growth.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Money, sex and happiness: An empirical study. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106(3), 393–415.

Chang, G. (2002). The cause and cure of China’s widening income disparity. China Economic Review, 13, 335–342.

Chen, X. (2015). Status concern and relative deprivation in China: Measures, empirical evidence, and economic and policy implications, IZA DP No. 9519.

Chen, X., & Zhang, X. (2009). The distribution of income and well-being in rural China: A survey of panel data sets, studies and new directions. MPRA paper 20587, http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/20587.

Chen, X., & Zhang, X. (2012). Costly posturing: Relative status, ceremonies and early child development in China. United Nations UniversityWIDER Working Paper, No. 2012/70.

Clark, A. E. (2003). Inequality-aversion and income mobility: A direct test, DELTA Working Paper, 2003-11.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 53–72.

Deaton, A. (2012). The financial crisis and the well-being of Americans. Oxford Economic Papers, 64(1), 1–26.

Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2013). Two happiness puzzles. The American Economic Review, 103(3), 591–597.

Easterlin, R., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(25), 9775–9780.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Gowdy, J. M. (2007). Environmental degradation and happiness. Ecological Economics, 60(3), 509–516.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. The Economic Journal, 110(466), 918–938.

Frijters, P., Liu, A. Y. C., & Meng, X. (2012). Are optimistic expectations keeping the Chinese happy? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81(1), 159–171.

Grosfeld, I., & Senek, C. (2010). The emerging aversion to inequality: Evidence from subjective data. Economics of Transition, 18(1), 1–26.

Hirschman, A. O., & Rothschild, M. (1973). The changing tolerance for income inequality in the course of economic development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(4), 544–566.

Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jiang, S., Lu, M., & Sato, H. (2012). Identity, inequality, and happiness: Evidence from urban China. World Development, 40(6), 1190–1200.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010a). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural-urban migrants in China. World Development, 38(1), 113–124.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010b). The rural–urban divide in China: Income but not happiness? The Journal of Development Studies, 46(3), 506–534.

Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Economic Review, 20(4), 635–649.

Lei, X., Shen, Y., Smith, J. P., & Zhou, G. (2015). Do social networks improve Chinese adults’ subjective well-being? The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 6, 57–67.

Lerner, A. P. (1944). The economics of control: Principles of welfare economics. New York: Macmillan.

Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 963–1002.

Oshio, T., Nozaki, K., & Kobayashi, M. (2011). Relative income and happiness in Asia: Evidence from nationwide surveys in China, Japan, and Korea. Social Indicators Research, 104(3), 351–367.

Senik, C. (2004). When information dominates comparison: Learning from Russian subjective panel data. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2099–2123.

Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Broderick, J. E., & Deaton, A. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 107(22), 9985–9990.

Strauss, J., & Thomas, D. (2008). Health over the life course. In T. P. Schultz & J. Strauss (Eds.), Handbook of development economics, Vol. 4. Amsterdam: North Holland Press.

Veenhoven, R. (1995). Review of global report on student well-being. Volume 1, Life satisfaction and happiness. Social Indicators Research, 34(1), 171–174.

Xie, Yu, & Zhou, X. (2014). Income Inequality in Today’s China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(19), 6928–6933.

Zhao, Y. (2002). Causes and consequences of return migration: Recent evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 30(2), 376–394.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Natural Science Foundation and Tianjin Social Science Foundation (ZX20160145). Thanks to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, X., Shen, Y., Smith, J.P. et al. Life satisfaction in China and consumption and income inequalities. Rev Econ Household 16, 75–95 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9386-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9386-9