Abstract

This paper analyzes peer effects among siblings in the decision to leave parental home. Estimating peer effects is challenging because of problems of reflection, endogenous group formation, and correlated unobservables. We overcome these issues using the exogenous variation in siblings’ household formation implied by the eligibility rules for a Spanish rental subsidy. Our results show that sibling effects are negative and that these effects can be explained by the presence of old or ill parents. Sibling effects turn positive for close-in-age siblings, when imitation is more likely to prevail. Our findings indicate that policy makers who aim at fostering household formation should target the household rather than the individual and combine policies for young adults with policies for the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The proportion of young adults living with their parents is three times higher in Southern European countries than in Northern European ones.Footnote 1 Moreover, this proportion has increased sharply in Southern Europe during the last three decades.Footnote 2 Policy makers are concerned about young adults late household formation because it may critically affect family formation decisions, overall fertility rates, youth labour supply, labour mobility, and the sustainability of pay-as-you-go pension systems. As a consequence, several governments have implemented measures or advocated the need for incentives to promote household formation (for instance, the Portuguese “Porta 65” program in 2007, the Spanish “Renta Basica di Emancipacion” in 2008, and the French “Aide Mobili-Jeune” in 2013).

Social interactions are particularly interesting for policy makers because they may alter the impact of policies. In the presence of peer effects in household formation, individuals’ decision to leave parental home in response to a policy could affect their peers’ household formation decision, even when the latter are not directly affected by the reform. Among social interactions, siblings’ ones are particularly interesting because, differently from other peer interactions, they happen within the household and they are more intense and lasting. In fact, siblings have often been found to be the most influential peers (Lindahl 2011; Nicoletti and Rabe 2013; Dahl et al. 2014). This paper analyzes sibling effects in the decision to form a new household, i.e., the impact of having a sibling who forms a new household in the same time period.

Sibling effects in household formation can be positive or negative. They can be positive due to imitation or information transmission. Imitation among siblings may reflect an intrinsic desire to behave like others and is stronger for smaller age differences and from older to younger siblings (Barr and Hayne 2003). The decision of an individual to form a new household may also reflect information transmission about the costs and benefits of leaving parental home, so that the choices of any single person modify the information available to all her siblings (Duflo and Saez 2003). However, sibling effects may also operate in the opposite direction (Angrist and Lang 2004). First, if a sibling has left parental home, the quantity of public goods available for the remaining siblings increases, reducing their incentive to form a new household. Parents may also increase household resources to the remaining sibling in response to the higher risk of remaining alone: Manacorda and Moretti (2006) show that if children have a preference for living on their own, some parents are willing to trade off their own consumption to bribe their children into staying at home. Second, children of lone parents are observed leaving the nest at a lower rate (Mencarini et al. 2012). In this case, an individual’s decision to leave parental home may induce her siblings to stay home. Similarly, the presence of old or ill parents may delay young individuals’ household formation in response to their siblings’ decision to leave parental home if remaining children need to stay home to take care of the parent.Footnote 3 In our empirical analysis, we determine whether positive or negative sibling effects prevail in practice.

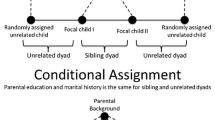

Estimating causal effects arising from social interactions is challenging. As Manski (1993) pointed out, estimation of these effects needs to deal with problems of simultaneous causality, correlated unobservables, and endogenous group membership. Researchers have used different strategies to tackle these issues. Some authors attempt to control for as many observable characteristics as possible, or use instrumental variables.Footnote 4 Others identify peer effects by exploiting exogenous group assignment.Footnote 5 A third approach consists in studying peer effects in naturally occurring groups, and exploiting random variation in exposure to the treatment for a random subset of individuals.Footnote 6 This last strategy is called partial population approach (Moffitt 2001). The exogenous variation in the papers that adopt the partial population approach often comes from policies or legislation changes. Angelucci et al. (2010) and Lalive and Cattaneo (2009) exploit a randomized intervention in the context of the Progresa aid program, Dahl et al. (2014) analyze the introduction of the Norwegian paternity leave quota in 1993 and Hesselius et al. (2009) study the deferral of the monitoring of sickness absence for a group of randomly selected individuals in Sweden.

We follow the partial population approach and examine the causal effect of a sibling’s household formation decision on the individual’s probability of leaving parental home. We use data from the Spanish Survey on Income and Living Conditions which follows individuals over time, even when forming a new household. Our identification strategy makes use of the panel structure of the data and the exogenous eligibility criteria for a Spanish rental subsidy that significantly affects household formation rates. The panel data nature of our sample allows us to difference out any individual or household time-invariant unobservable characteristic; the exogenous eligibility criteria for the rental subsidy allow us to deal with other omitted variables as well as reverse causality concerns. Our findings suggest that there are negative siblings’ effects on household formation: youngsters who leave their parental home delay their siblings’ decision to leave. When looking at the mechanisms, negative sibling effects can be explained by the remaining sibling staying longer in the parental home in the presence of an old or ill parent. The effect could be led by female individuals staying at home after their sister has left parental home. Estimated sibling effects turn positive for close-in-age siblings. Overall, siblings’ interactions reduce the impact of policies that foster household formation unless age differences between siblings are small.

There is some evidence on the effects of peer behavior in living arrangements. Using Italian data, Di Stefano (2008) estimates a structural model in which young adults simultaneously choose labor supply, residential arrangement and marital status conditional on the social norm on the age at first marriage, endogenously determined as an equilibrium outcome. Although she does not analyze specifically sibling effects, her results indicate that young adults, and especially women, tend to conform to each other, which is a sign of the existence of peer effects. Adamopoulou and Kaya (2015), using peers’ characteristics as an instrument for the fraction of peers who have left parental home, find evidence of positive peer effects among North-American high school friends. Numerous studies have produced empirical evidence documenting the existence of relevant siblings’ interactions in many areas.Footnote 7 To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to explore the role of sibling effects on the decision to leave parental home.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional setting and data. Section 3 presents the empirical methodology. Section 4 provides a discussion of the empirical results and Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Institutions and data

2.1 Institutional background

Announced in September 2007 and enacted since January 2008, the Basic Rent for Emancipation is a monetary subsidy introduced by the Spanish Ministry of Housing with the aim of fostering youngsters’ household formation. The government expected to achieve this goal by reducing young individuals’ rental expenses. The policy also aimed at promoting youngsters’ economic independence and geographical mobility.

The subsidy pays € 210 monthly for a maximum period of 4 years. Eligibles may also benefit from an additional € 120 to pay the bank guarantee associated with the rental contract, and a one-time € 600 loan to pay the rent deposit in case they sign a new rental contract. To appreciate the magnitude of the subsidy, it can be useful to compare it with the average Spanish youngsters’ monthly earnings. Average gross monthly earnings of young people in the 20–24 age brackets amount to € 1100 in 2008.Footnote 8 The subsidy is therefore equivalent to almost 20 % of the average gross salary of a young person. By July 2011, the subsidy was given to 35 % of households headed by an individual aged 22–29 (including both renters and homeowners). In September 2011, as a consequence of the worsening of the economic recession in Spain, the government announced the cancellation of the Renta Basica de Emancipacion, which came into force from the end of December 2011. New households formed after that date were not eligible for the rental subsidy. However, eligible households who applied for the rental subsidy before the end of 2011 still benefited after that date but received a lower amount of subsidy.

To be eligible for the subsidy, youngsters need to be in the 22–29 age bracket and have a rental contract. This includes individuals that had a rental contract before becoming eligible.Footnote 9 Those who do not have a rental contract may request the subsidy conditional on providing the contract signed in 3 months time. Eligibles need to certify that they are employed, autonomous workers, grant holders, or receivers of a periodic social benefit (including unemployment benefit). The latter are also required to have worked for at least 6 months or provide evidence that the social benefit will last for at least 6 months. For all the eligibles, the net source of income must not exceed € 1500 per month. EU citizens and non-EU citizens with a permanent resident permit are eligible. If several individuals are sharing accommodation, each young adult entitled to the subsidy receives a share of the subsidy proportional to the number of people who sign the rental contract. Individuals who rent out from close family members are not eligible. In our empirical analysis we define subsidy eligibility exclusively on the basis of age and time of the survey, the only criteria that are impossible to manipulate.Footnote 10

2.2 Data

Our main dataset consists of the 2005–2010 waves of the Spanish data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). The data contain a wide range of information on individual’s and household’s characteristics. Individuals are surveyed yearly and stay in the sample for four consecutive years. If an individual forms a new household during that time, both the old and the new households are interviewed. If the new household does not respond (in cases, for instance, in which the individual has died or moved abroad), the old household reports whether the individual has formed a new household.

The estimation sample includes 6435 individuals in the 18–34 age group living with their parents, and their siblings observed while living with their parents who are over 18 and at most 10 years older (in the 18–44 age group). We keep pairs of siblings 1 year after the sibling built up an independent household (79 out of 6435 observations) and even 2 years after the sibling built up a household (6 out of 6435 observations).Footnote 11 The panel is unbalanced: individuals who become 18 during the survey period enter the sample only after they turn 18. Similarly, individuals who become 34 during the survey period exit the sample as soon as they turn 34. The sample is composed by all pairs of siblings, and as in Altonji et al. (2015) we focus on the effect of the older sibling’s household formation on the younger individual’s one. We select the period 2005–2010, as the cancellation of the policy was announced in 2011 and enacted from the end of that year.

Building up an independent household is measured by a dummy equal to one in the year in which the individual (the sibling) leaves parental home and the years following that.Footnote 12 Sibling’s household formation is defined with a dummy equal to one if the sibling has left the parental home in the same time period. Our analysis focuses on how the policy affects flows out of the parental home, and therefore indirectly the stock of individuals living independently from their parents.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the whole sample, the sample of individuals interviewed in the pre-policy period (2005–2007), the sample of individuals interviewed in the post-policy period (2008–2010), the sample of individuals with no-eligible siblings and the sample of individuals with eligible siblings. Almost 60 % of individuals in the sample live with their parents, around 4.6 % of the sample has left parental home over the period 2005–2010 and 10.2 % of individuals have at least one sibling who has left parental home over the same time period, with both statistics being slightly higher in the post-policy period. Individuals with no-eligible siblings leave parental home at a higher rate than those with eligible siblings, suggesting that the policy may induce the remaining individuals to stay home after one sibling has left. Around 60 % of siblings are eligible for the rental subsidy in the post-policy period. Slightly more than half of respondents are male. Siblings in the sample are around 4 years older than individuals (26 vs. 21.7 years of age). As a consequence, siblings have a higher probability of having completed secondary education (61 vs. 48 % in the sample of individuals) and tertiary education (28 vs. 11 % in the sample of individuals), and an average higher gross annual income (€6934.55 vs. €3810.7 in the sample of individuals). Statistics on gross income, the regional yearly unemployment and GDP growth rates highlight how the macroeconomic conditions worsened in the post-policy period as a consequence of the economic recession.

The basic idea behind the identification strategy is illustrated in Fig. 1. The solid lines show the trends in household formation rates of individuals with and without eligible siblings. The figure shows that the trends were parallel before the policy was implemented, and diverge after the introduction of the policy, illustrating the source of exogenous variation of our identification strategy. The trend in household formation rates of individuals who have eligible siblings lies below that of those who have non-eligible siblings. This happens because individuals with eligible siblings are younger on average, although the age difference is not significant. The two trends diverge slightly from 2008 to 2009 and start diverging significantly after 2009. This delay can be explained by the nature of our data. Individuals that report having formed a household in 2009 have actually done it at any point in time between their interview in 2008 and the interview in 2009. The two dashed lines above and below each solid line represent confidence intervals. The confidence intervals present significant overlap in the pre-treatment period which suggests that the two groups are not significantly different in terms of the characteristics that drive the decision to form a new household. The overlap is significantly reduced after the implementation of the policy, mainly due to the divergence between the two trends.

3 Empirical strategy

Peer effects occur when an individual’s action influences the action of another individual in the same social group. However, measuring peer effects has proven difficult (Manski 1993). First, if peers i and j affect each other, then it is difficult to separate out the actual causal effect that individual i’s outcome has on individual j’s outcome. This is commonly called the reflection problem and it is likely to arise whenever individual and peer behaviour are determined simultaneously. Second, unobserved group characteristics and individual traits that are correlated within the group may induce artificial correlation among peer outcomes. Finally, self-selection in peer groups represents another challenge in the estimation of peer effects.

In our setting, the first two challenges are present: siblings are likely to influence each other; and unobservable family and individual characteristics, such as strength of family ties, taste for independence and privacy, are likely unobserved and correlated among siblings. However, self-selection is not an issue in the context of exogenously-formed peer groups as siblings.

Our objective is to obtain an estimate that is informative about the causal effect of sibling’s choices on individual’s household formation. To this, we follow Moffitt (2001) and Dahl et al. (2014) partial population approach, which exploits quasi-random variation in the net benefit of participating to a treatment for some individuals in a group and see how other members in the group change their behavior. In particular, we take advantage of the exogenous increase in the propensity to form a new household for siblings in the 22–29 age range induced by the introduction of the Spanish rental subsidy in 2008 and see how individuals in the 18–21 and 30–34 age groups change their behaviour. Our identification strategy relies on exogenous variation in siblings’ eligibility for the rental subsidy. We exploit two sources of variation. One source of variation is determined by the year of the interview. Siblings interviewed before 2008 did not benefit from the program, since the rental subsidy only came into force in January 2008 and hence, only some siblings interviewed after that date were fully eligible. The other source of variation arises from age. Due to the eligibility criteria established by the law, only siblings in the 22–29 age group were entitled to the subsidy. In order to get a sense of the correlation between siblings’ household formation decisions, we estimate the following equation by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS):

where \(y_{i,t}\) is a dummy equal to one if individual i has left parental home in period t and \(y_{j,t}\) is the corresponding value for sibling j. The coefficient \(\alpha _{1}\) captures the effect of having a sibling who has formed a new household on the individual’s probability of leaving parental home; \(e_{j}\) is a dummy variable for sibling j being in the 22–29 age group, \(t_{t}\) is a time dummy equal to one for individuals and siblings interviewed in 2008 and after. The vectors \(X_{i,t}\) and \(X_{j,t}\) contain the following control variables: year dummies, individual’s and sibling’s male dummy, individual’s and sibling’s log of age, individual’s and sibling’s secondary and tertiary education dummies (education level attained in the previous year), individual’s and sibling’s gross yearly income (earned in the past year), dummy for individual’s region of residence (Comunidades Autonomas by their Spanish name), and dummies for the month of interview, which capture the “seasonality effect”, i.e., any systematic differences in household formation rates implied by the calendar period of the year. Finally, as the subsidy was introduced in the same year as that in which the economic recession began, we include controls for the regional yearly unemployment and GDP growth rates to isolate the potential effect of the recession. \(\lambda _{i,j}\) represents the vector of the sibling-pair fixed effects and \(\varepsilon\) is the error term. We cluster residuals at the household level to account for unobservable household characteristics, including taste for independence and attachment to the family. Unfortunately, the OLS estimated \(\alpha _{1}\) coefficient would be biased due to reflection and correlated unobservables.

For our identification strategy to be meaningful, we first need the subsidy to be effective in promoting household formation in the sample of siblings. To check this we estimate the following specification by OLS:

where the coefficient \(\beta _{3}\) captures the effect of the sibling being eligible for the subsidy on the probability that the sibling forms a household.

In our baseline specification, we assume household formation is a function of the siblings’ subsidy eligibility and individual controls. This corresponds to the reduced-form equation of the model that provides the intention-to-treat estimates (ITT) by OLS. The equation reads as follows:

where the coefficient \(\gamma _{3}\) captures the causal impact of a sibling’s eligibility on the individual’s probability of leaving parental home. Note that in our main specification we estimate the effect of sibling’s eligibility on the individual’s likelihood of leaving the nest in the same year.

The validity of the estimation proposed in Eq. (3) relies on the use of panel data and the exogeneity of the rental subsidy. The panel data nature of our sample allows us to difference out any sibling-pair fixed over time unobservable component.Footnote 13 However, in the context of a standard fixed-effect estimation, it remains difficult to rule out the possibility of reverse causality and time varying unobservables. The exogenous change induced by the rental subsidy addresses concerns arising both from potential reverse causality and omitted variables: individual household formation does not affect sibling’s eligibility and hence, the use of the dummy for sibling’s subsidy eligibility rather than sibling’s household formation solves the reverse causality problem. Moreover, as a consequence of the policy design, the sibling’s eligibility dummy \(e_{j}t_{t}\) is orthogonal to any unobserved covariates and hence correlated unobservables can no longer bias the estimates.

Equation (3) is informative about how policies promoting individuals’ household formation affect their siblings. However, it is also a reduced form approach to estimate sibling effects on household formation. For the latter purpose, we could have opted for a two-stage least-squares (TSLS) estimate in which subsidy eligibility serves as an instrument for sibling’s household formation. To consistently estimate the size of the sibling effect via TSLS, one also needs to assume that the only channel through which individuals are affected by siblings’ eligibility is siblings’ household formation. This could be problematic if household formation means something different before and after the subsidy implementation, with individuals forming a household in the post-policy period sending a different signal to their siblings. TSLS also requires the monotonicity assumption that the subsidy would not induce any young individuals to stay longer at parental home which may have happened if the subsidy increased competition for accommodation. Moreover, the assumptions required for the estimation of average treatment effects by TSLS are incompatible with the discrete nature of the outcome, the endogenous variable and the instrument (Chesher and Rosen 2013). Finally, the alternative option of non-parametric instrumental variable approach as in Chesher (2009) delivers too wide intervals in our case.

4 Results

4.1 Individual and sibling’s household formation: OLS regression

We first report the results of the naive estimation of the coefficients \(\alpha _{0}- \alpha _{3}\) of Eq. (1) by OLS in Table 2. The first column shows the specification that controls for individual’s characteristics, in the second we add sibling’s characteristics and in the third one we also include macroeconomic time varying controls. In each column we control for the sibling being in the 22–29 age group, the dummy for being interviewed in the post-policy period, and for sibling-pair fixed effects. The OLS estimates show positive and significant correlations between sibling’s household formation in all specifications, with the effect slightly decreasing when we include sibling’s characteristics, and not being affected by the inclusion of the macroeconomic variables.

The positive correlation between individual and sibling’s household formation could be easily justified by the common background shared by siblings or be an outcome of the reflection problem. To learn about causal effects, we next interpret the specifications that use subsidy eligibility as an explanatory variable.

4.2 The impact of the subsidy on sibling’s household formation

Our identification strategy relies on the effectiveness of the rental subsidy in fostering household formation among siblings. Table 3 presents estimates of the coefficients \(\beta _{0}-\beta _{3}\) in Eq. (2). The different columns replicate the structure of Table 2. The coefficient of interest is the interaction between the dummy for being interviewed after 2008, and the dummy for the sibling’s being in the 22–29 age group, which captures the sibling’s eligibility to the subsidy. The coefficient is positive and statistically significant in all three specifications. The size of the coefficient slightly increases after the inclusion of the sibling’s controls but it remains unaffected by the inclusion of the macroeconomic controls. The coefficient in the full sample indicates that subsidy eligibility increases the propensity to leave the nest by 5 %. These estimates are higher than those obtained by Aparicio and Oppedisano (2014), who estimated a lower bound effect of 3 %. A possible explanation for the higher coefficient could rely on the fact that the time frame used in the two papers is different: while in the previous paper we focused on the 2006–2009 time period, here we look at the 2005–2010 time period. If it takes time for the policy to be known among eligible young adults and for the applications for the subsidy to be processed, the effect of the policy should increase over time, and be on average larger if a wider time frame is considered.Footnote 14 The F test in the last row of Table 3 indicates that although the policy is effective in promoting siblings’ household formation, it cannot be used as an instrument in a TSLS estimation. Therefore, in the rest of the paper we mainly focus on the reduced form specification.

4.3 The impact of sibling’s eligibility on household formation

Results in Table 3 show that siblings’ eligibility for the rental subsidy significantly affects the probability that a sibling leaves the nest. In this section, we exploit the exogenous variation in exposure to the subsidy across youngsters, to assess the causal impact of the sibling’s eligibility to the subsidy on the probability of forming a new household.

We estimate Eq. (3) and focus on the interaction between the post policy dummy and the dummy equal to one if the older sibling is in the 22–29 age group. Table 4 shows that the estimate of the impact of sibling’s subsidy eligibility on household formation is negative and significant at 1 % level in all specifications. In terms of magnitude, sibling’s subsidy eligibility decreases the probability of leaving the nest by 5.7 % age points in the specification with the full set of controls. Thus, the direction of the effect estimated in the reduced form specification is opposite to the positive effect delivered by the naive OLS estimation.

4.4 Mechanisms and alternative specifications

Next, we explore the mechanisms behind the estimation results in Table 4. We then analyze whether results change for close-in-age siblings. To achieve the first objective, we interact the sibling’s eligibility dummy with a set of time varying parental characteristics. Results are reported in Panel A of Table 5. In the first column, we include the interaction of the sibling’s eligibility dummy with a dummy indicating whether the youngest parent is less than 50 years old. This interaction has a positive and significant effect on individual’s household formation. The magnitude of the coefficient is such that it completely offsets the overall negative effect, suggesting that parental age can be behind the negative sibling effect: if the youngest partner is more than 50 years old then the household formation decision of one sibling will induce the other one to remain in the parental home. Differently, the presence of a younger than 50 years old parent, who may take care of the older partner, will not deter the individual’s decision to leave parental home after the sibling has left.

In the second column, the sibling’s eligibility dummy is interacted with a dummy equal to one if at least one of the parents is healthy. This dummy is constructed from a survey question about the individual’s general health status. Respondents can define their health status as very good, good, regular, bad or very bad. We define an individual to be healthy if her health status is regular, good, or very good. The coefficient of the interaction between the sibling’s eligibility dummy and the dummy for at least one healthy parent is positive and statistically significant. The magnitude of the estimated coefficient is such that it offsets more than 75 % of the overall effect. This result indicates that another channel through which negative sibling effects arise is through parental health: if none of the parents is healthy and one sibling leaves the nest, the other sibling will respond by remaining in the parental home. If at least one parent is healthy (the reference category) the remaining sibling does not show a lower probability of forming a household. The third column of the upper panel of Table 5 shows the interactions of the eligibility dummy with the individual’s and sibling’s gender combinations.Footnote 15 Results do not show any significant gender difference but suggest that if there were gender differences, the effect will be driven by women with emancipating sisters, consistently with the hypothesis that parental caregiving activities are often females’ duties.

In Panel B of Table 5, column one and two report the interactions of the sibling’s eligibility dummy with the sibling’s education and income level and show that the sibling’s income and education seem to increase the magnitude of the negative sibling effect.Footnote 16 Our results suggest that the decision to leave parental home could depend on the completion of education and on a sufficiently high level of income. If attitudes towards risks and tastes are correlated between siblings, individuals may learn from their siblings that they should stay at the parental home while they are students or until they earn a sufficient level of income.

Negative siblings’ effects may also arise because the remaining sibling may take advantage of the higher quantity of public goods available to her as a consequence of her sibling having left the parental home. We try to assess this effect using the number of rooms in the house at the time the household is interviewed for the first time as a proxy for public good. In unreported regressions, we do not find that individuals living in smaller houses are more likely to leave the nest than those living in larger houses, and we therefore tend to count out that public goods as measured by the space in the house explain negative sibling effects.

Note that negative siblings’ effects can also be explained by an increase in household resources enjoyed by the remaining children if parents are willing to bribe their children into staying at home. Unfortunately, our data do not convey information on transfers from parents to the child, and therefore we cannot assess the importance of this mechanism in siblings’ interactions.

Next, we explore whether the sibling effect is different if we consider the sample of close-in-age siblings. Following Barr and Hayne (2003), we hypothesize that close in age siblings are more likely to imitate each other. We define a dummy variable equal to one if siblings are at most 2 years apart. Results are reported in column 3 of Panel B of Table 5. The coefficient of this interaction is positive and statistically significant, and not only it offsets the negative effect of the sibling’s eligibility interaction, but it exceeds it. This indicates that sibling effects become positive for close-in-age siblings: when individuals leave the nest, their less-than-2-years younger siblings are more likely to follow them in the decision to form a new household.

In order to check whether differences in the impact of the economic crisis on employment prospects of different age groups could be behind our result, we replicated our main regression (Eq. 3) using employment as a dependent variable instead of household formation. Results show that there is no significant difference in employment changes between age groups and if anything individuals with eligible siblings are more likely to be employed and hence to afford household formation (see Table 6).

TSLS would be a valid estimation strategy under the additional assumptions of monotonicity and the exclusion restriction. In an unreported regression, the coefficient of the specification with the full set of controls is negative and statistically significant at 10 % level, indicating that the individual decision to leave parental home reduces the sibling’s probability of forming a new household, confirming the direction of the sibling effects. As we mentioned in Sect. 3, the assumptions required for the estimation of average treatment effects by TSLS are incompatible with the discrete nature of the outcome, the endogenous variable, the instrument and most of our controls. Moreover, the F test indicates the weakness of the first stage for our sample. Therefore, we omit a detailed interpretation of the size of the TSLS coefficients, as it is uninformative of the true size of the effect in this setting.

In all our analysis we study contemporaneous sibling effects, showing the effect of a sibling’s eligibility on the individual’s choice to form a new household in the same year. However, it may be interesting to look at whether these effects persist, or dissipate over time. As individuals are interviewed only four times, we can analyze the effect of sibling’s eligibility on next year probability that the individual will leave parental home.

In an unreported regression we estimate Eq. (3) with a lagged (rather than contemporaneous) sibling’s eligibility dummy. Results show that siblings’ eligibility 1 year before reduces the probability of the individual’s forming a new household by 2.5 %. However, the effect is not significant at conventional levels, suggesting that the negative impact may fade out 1 year later.

Finally, we provide further evidence on the validity of our difference-in-differences estimation strategy and perform a placebo test pretending that the policy was implemented in 2007. The results of this exercise are reported in Table 7. Estimated coefficients are small in magnitude and non-significant, indicating that there are no pre-existing trends in the data that could drive our results. The same happens when we pretend that the policy was implemented in 2006.

5 Conclusion

The transition to adulthood is a complex process made of several interrelated steps such as leaving school, finding a job, finding a partner, etc. It culminates with the formation of an independent household, possibly with a partner, and usually implies moving out of the parental residence. The increasingly late age at which young adults in Southern Europe postpone household formation decisions has led governments, in the last decade, to implement policies that foster the decision to leave the nest, by reducing young adults’ rental expenses. If peer effects among siblings in the choice of leaving parental home exist, then these incentives may amplify or reduce the aggregate impact of these policies depending on whether sibling effects are positive or negative, which remains an open empirical question.

We empirically analyze the role of sibling effects on household formation decisions in the context of Spain, a Southern European country characterized by late household formation. To this, we make use of the exogenous variation in household formation for a subset of young individuals eligible for the rental subsidy, and exploit the panel data dimension of the EU-SILC data. Our results suggest that siblings’ interactions reduce the impact of policies that foster household formation, except for the case in which subsidy recipients are close-in-age siblings, consistently with the hypothesis that the willingness to imitate a sibling is stronger in correspondence of small age gaps. When exploring the channels through which negative sibling effects are exerted, we find that individuals who further delay the decision to form a new household after a sibling has left do so in presence of old or ill parents. Moreover, results suggest that individuals learn from their siblings that they should stay at the parental home while they are students or until they earn a sufficient level of income. We cannot rule out with available data that the enjoyment of higher public goods for the remaining sibling, or transfers from the parents that try to bribe the remaining children at home are other mechanisms at play.

Overall, in the context of Southern European countries, where family ties are strong, there is more reliance on home production and less participation in market activities as individuals tend to trust more family members (Alesina and Giuliano 2010). Caring for the elderly is a typical activity demanded to household production in these countries. A policy that aims at fostering the household formation process should account for household composition as well. In particular, our findings indicate that policy makers should target the household rather than the individual. Policy makers should also combine policies for young adults with policies for elderly.

Notes

In 2010, almost 60 % of young people in the 18–34 age bracket lived in their parental homes in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, whilst that statistic is below 40 % in France, the UK, and the Netherlands, and as low as 20 % in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC.

Angelini and Laferrère (2013) show that both cultural traits and the parental ability to help their children by either providing them with a home, or with a financial transfer to move out, affected the nest living patterns over time and across European countries. For an analysis on the heterogeneity of parental altruism across countries see Horioka (2014).

Children may offer caregiving activities out of altruism for their parents, or in exchange for monetary incentives offered by the family members benefiting from the services received. See Grossbard (2014) for a discussion on the motives behind caregiving.

Source: Spanish Wage Structure Survey, 2008.

Note that the policy does not generate incentives to postpone emancipation for 21 year-olds. Emancipated 21 year-olds will be entitled to the same amount of subsidy as soon as they become eligible. Aparicio and Oppedisano (2014) provide an empirical test that confirms that postponement is not significant.

Aparicio and Oppedisano (2014) show that the majority of individuals who were eligible in terms of age actually fulfilled all other criteria.

We ran our regressions omitting observations for the years after the sibling emancipated and results are very similar to those obtained when they are included. Results are available from the authors upon request.

The time frame does not include 2005 because, for individuals interviewed in 2005, we observe household formation decisions from 2006.

We also estimated all the outcomes using household and individual fixed effects and results are invariant.

Spanish newspapers documented that some regions experienced delays in processing the subsidy during the first months of its application due to lack of communication between administrative entities (El Pais, 05/02/2008).

The coefficients of the dummies for the combinations of individual’s and sibling’s gender are not identified as they are absorbed by the sibling-pair fixed effects.

The variable sibling’s education reflects the number of completed levels of education. This is, it equals 0 for siblings who did not complete any educational level, 1 for siblings who completed the first level (primary education), 2 for siblings who hold the second level diploma (secondary education) and 3 for siblings who completed the third level (tertiary education).

References

Adamopoulou, E., & Kaya, E. (2015). Young adults living with their parents and the influence of peers. Cardiff Economics Working Paper, E2015/12.

Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2010). The power of the family. Journal of Economic Growth, 15(2), 93–125.

Altonji, J. G., Cattan, S., & Ware, I. (2015). Identifying sibling influence on teenage substance use. Journal of Human Resources (forthcoming).

Angelucci, M., De Giorgi, G., Rangel, M., & Rasul, I. (2010). Family networks and school enrolment: Evidence from a randomized social experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 94, 197–221.

Angelini, V., & Laferrère, A. (2013). Parental altruism and nest leaving in Europe: Evidence from a retrospective survey. Review of Economics of the Household, 11(3), 393–420.

Angrist, J. D., & Lang, K. (2004). Does school integration generate peer effects? Evidence from Boston’s Metco program. American Economic Review, 94, 1613–1634.

Aparicio, A., & Oppedisano, V. (2014). Fostering household formation: Evidence from a Spanish rental subsidy. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy. doi:10.1515/bejeap-2014-0003.

Baird, S., Bohren, A., McIntosh, C., & Ozler, B. (2014). Designing experiments to measure spillover and treshold effects. University of Pennsylvania PIER Working Paper No. 14-006.

Barr, R., & Hayne, H. (2003). It’s not what you know, it’s who you know: Older siblings facilitate imitation during infancy. International Journal of Early Years Education, 11, 7–21.

Bayer, P., Ross, S., & Topa, G. (2008). Place of work and place of residence: Informal hiring networks and labor market outcomes. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 1150–1196.

Björklund, A., Eriksson, T., Jantti, M., Raaum, O., & Osterbacka, E. (2002). Brother correlations in earnings in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden compared to the United States. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 757–772.

Björklund, A., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Education and family background: Mechanisms and policies. Handbook of the Economics of Education, Elsevier.

Burke, M. A., & Sass, T. R. (2013). Classroom peer effects and student achievement. Journal of Labor Economics, 31, 51–82.

Carrell, S., Malmstrom, F., & West, J. (2008). Peer effects in academic cheating. Journal of Human Resources, 43, 173–207.

Carrell, S., Sacerdote, B., & West, J. (2013). From natural variation to optimal policy? The importance of endogenous peer group formation. Econometrica, 81(3), 855–882.

Chesher, A. (2009). Single equation endogenous binary response models. Cemmap WP CWP23/09.

Chesher, A., & Rosen, A. (2013). What do instrumental variable models deliver with discrete dependent variables? The American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 103, 557–562.

Dahl, G. B., Løken, K. V., & Mogstad, M. (2014). Peer effects in program participation. American Economic Review, 104, 2049–2074.

Di Stefano, E. (2008). Leaving your mama: Why so late in Italy? University of Minnesota Working Paper.

Duflo, E., & Saez, E. (2003). The role of information and social interactions in retirement plan decisions: Evidence from randomized experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 815–842.

Gaviria, A., & Raphael, S. (2001). School-based peer effects and juvenile behavior. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83, 257–268.

Grossbard, S. (2014). A note on altruism and caregiving in the family: Do prices matter? Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 487–491.

Hensvik, L., & Nilsson, P. (2010). Businesses, buddies and babies: social ties and fertility at work. IFAU-Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation Discussion paper.

Hesselius, P., Nilsson, P., & Johansson, P. (2009). Sick of your colleagues absence? Journal of the European Economic Association, 7, 583–594.

Horioka, C. Y. (2014). Are Americans and Indians more altruistic than the Japanese and Chinese? Evidence from a new international survey of bequest plans. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 411–437.

Hoxby, C. (2000). Peer effects in the classroom: Learning from gender and race variation. NBER Working Papers 7867, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Katz, L., Kling, J. R., & Liebman, J. B. (2001). Moving to opportunities in Boston: Early results of a randomized mobility experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 607–654.

Kuziemko, I. (2006). Is having babies contagious? Fertility peer effects between adult siblings. Princeton University Working Paper.

Lalive, R., & Cattaneo, M. (2009). Social interactions and schooling decisions. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91, 457–477.

Lindahl, L. (2011). A comparison of family and neighborhood effects on grades, test scores, educational attainment and income—Evidence from Sweden. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(2), 207–226.

Manacorda, M., & Moretti, E. (2006). Why do most Italian youths live with their parents? Intergenerational transfers and household structure. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4, 800–829.

Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. The Review of Economic Studies, 60, 531–542.

Maurin, E., & Moschion, J. (2009). The social multiplier and labor market participation of mothers. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1, 251–272.

Mazumder, B. (2008). Sibling similarities and economic inequality in the US. Journal of Population Economics, 21, 685–701.

Mencarini, L., Meroni, E., & Pronzato, C. (2012). Leaving mum alone? The effect of parental divorce on children leaving home decisions. European Journal of Population, 28(3), 337–357.

Moffitt, R. (2001). Policy interventions, low-level equilibria, and social interactions. In S. N. Durlauf & H. Peyton Young (Eds.), Social dynamics (pp. 45–82). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nicoletti, C., & Rabe, B. (2013). Inequality in pupils’ test scores: How much do family, sibling type and neighbourhood matter? Economica, 80, 197–218.

Nicoletti, C., & Rabe, B. (2014). Sibling spillover effects in school achievement. ISER Working Paper Series 2014-40, University of Essex.

Sacerdote, B. (2001). Peer effects with random assignment: Results for Dartmouth roommates. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 681–704.

Schnitzlein, D. (2014). How important is the family? Evidence from sibling correlations in permanent earnings in the US, Germany and Denmark. Journal of Population Economics, 27, 69–89.

Solon, G., Corcoran, M., Gordon, R., & Laren, D. (1991). A longitudinal analysis of siblings correlations in economic studies. Journal of Human Resources, 26, 509–534.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank for useful suggestions Cristian Bartolucci, Alex Tetenov, Cheti Nicoletti, seminar participants at EALE conference in Turin, University College Dublin, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Freiburg University, and the Spanish Economic Association conference in Mallorca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aparicio-Fenoll, A., Oppedisano, V. Should I stay or should I go? Sibling effects in household formation. Rev Econ Household 14, 1007–1027 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9325-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9325-1