Abstract

We study the impact of different regulatory designs on the cost efficiency of operators providing a public service, exploiting data from the French transport industry. The distinctive feature of the study is that it considers regulatory regimes as endogenously determined choices, explained by economic, political, and institutional variables. Our approach leans on a positive analysis to study the determinants of regulatory contract choices, which, in turn, affect the costs of operating urban public transport. Our results show that given similar network characteristics, networks operated under fixed-price contracts exert lower costs than those regulated under cost-plus contracts. This finding is in line with the theoretical prediction of new regulatory economics that fixed-price contracts provide more incentives for efficiency. Importantly, ignoring the endogeneity of contractual choices would lead to significantly underestimating the impact of contract type on cost efficiency. Our findings provide useful policy implications suggesting that the move toward more high-powered incentive schemes is indeed associated with significant cost efficiencies. Moreover, they highlight the importance of accounting for the endogeneity of regulatory contract choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last decades, the European market has experienced several episodes of deregulation. In this respect, in many industries, competition for the market is increasingly used by public authorities. Once the ‘best’ operator is selected via a competitive bidding procedure, the key question is how to design good regulatory rules. Determining the impact of different regulatory designs on the cost efficiency of operators responsible for providing a public service is an important issue, with public procurement currently representing 14% of EU GDP (see EC 2017). While there are studies attempting to tackle this issue, they often ignore the endogeneity of contractual choices. Comparing different regulatory designs without taking into account that contracts are not necessarily randomly assigned may lead to false conclusions.

The objective of this study is to assess the impact of different contractual choices (fixed-price versus cost-plus) on cost efficiency by exploiting data from the French urban public transport industry. The distinctive feature of our study is that it addresses the endogeneity of contractual arrangements, by accounting for economic, institutional, and political issues put forward in the literature related to the design of regulatory contracts. Thus, the approach leans on a positive analysis to study the determinants of regulatory contract choices, which, in turn, affects the costs of operating urban public transport. While our paper is closely related to Gagnepain and Ivaldi (2017), it focuses on a more comprehensive and sophisticated analysis of the role of political aspects. Following a reduced form approach, we do not rely on (often unstable) structural assumptions. We also consider a more flexible representation of operators’ costs and cover a more up-to-date and extended database covering the years 1995–2010. To our knowledge, there has been no papers that allow a more up-to-date assessment od the industry.

The French urban public transport industry is particularly well suited for this study. In France, local public authorities are responsible for organizing urban public transport in their respective regions by defining, financing, and organizing regular public passenger transport within its urban network (composed of a city or group of cities). Each authority is given the choice to organize and provide the service itself or to delegate the relevant responsibilities to a transport operator (90% of networks, see GART 2015). The key feature of the French model is that the operation of the network is attributed to only one operator. The selected operator has the responsibility of providing the relevant service across the whole transport area throughout the duration of the contract. The relationship between the operator and the local authority is then regulated through an agreement. Regulatory contracts observed in the industry can be classified into two main categories: cost-plus and fixed-price. The choice of regulation translates into the division of risk-taking between the contracting parties (see Laffont and Tirole 1993), thus potentially affecting the cost efficiency of local transport operators. The characteristics of the industry also seem to suggest that contracts may not necessarily be randomly assigned. The organizing authorities are politicians representing the municipal council elected for approximately a six year period. The municipal council is governed by the mayor and has the legislative authority to manage the affairs of the municipality through its decisions. In this context, local authorities responsible for organizing transport services may be interested in re-election and, thus, will undertake actions to maximize political support favoring votes or campaign contributions in the next election. Those who leave the government may attempt to find high-level jobs in the industry they were previously responsible for regulating. Further, contractual choices may be explained by actions undertaken to prevent opportunistic behavior by their opponents. The opportunistic behavior could be understood as an action undertaken by the political opponent exposing or accusing the public manager to bad management with the purpose of replacing this opponent (see Moszoro and Spiller 2019). In line with this, the public manager, subject to elections, may increase the rigidity of a contract (opt for a fixed-price rather than cost-plus contract), the fiercer the electoral competition. In addition, most operators belong to major groups that may want to maximize profits aggressively and, therefore, may have a preference for fixed-price contracts. These operators may be willing to affect the regulatory decision in favor of their preferred contract. The French model of regulation, combining competitive tendering with negotiation, gives room for subjective selection criteria. Thereby, operators seem to have significant bargaining power when facing the regulator. Taking into account the characteristics of the actors involved in providing the service seems to be of particular importance when studying the French urban transport industry.

From a methodological standpoint, the industry is a good field for studying contractual choices and their impact on cost efficiency, as we can easily exploit variations in the conditions across local networks. First, we observe many local authorities making decisions about service provision at different points in time. These transport networks differ in a variety of interesting ways—by contract type in place, financial conditions, complexity, transport group to which the local operator belongs to, political color of local authority, etc. Second, contracts typically last seven to eight years. Consequently, when conducting an analysis of 1995 to 2010, we will observe several contractual periods for each network.

Understanding the rationale underlying regulatory choices in the industry that, in turn, affect the operating costs of the networks is of particular importance. In 2015, the financing needs of urban transport in France amounted to 8.9 billion Euros (see GART 2015). At the same time, the industry is facing strong financial constraints. While the industry has seen a significant increase in the supply of transport, this is not accompanied by a sufficiently strong demand for its services. As a result, the ratio of commercial receipts to operating costs is deteriorating. This situation further reinforces the need to improve the management of these services.

The contribution of the study to the existing literature is twofold. First, it analyzes the cost efficiency of transport operators as a function of regulatory schemes. There are few empirical papers analyzing the impact of regulatory schemes on cost efficiencies in the transport network (Gagnepain and Ivaldi 2002b; Piacenza 2006; Gautier and Yvrande-Billon 2013). However, these studies do not take into account that contracts are not necessarily randomly assigned, thus leading to potentially false conclusions.

Secondly, and most importantly, it addresses the gap in the literature with respect to the endogeneity of regulatory contract types that is, to our knowledge, extremely scarce and limited to few industries. Guasch et al. (2007) introduce an original instrumental variable strategy to address contract endogeneity in their study of government-led renegotiations in infrastructure concession contracts in Latin America. In explaining contractual choices, they include, among others, political and institutional factors, such as the degree of political capture of specific regulatory institutions, the tradition to expropriate investments in certain sectors, and political culture leading to different degrees of political interference with state-operators interactions. They also consider operator-specific variables, including the strategic skills of a firm to renegotiate contract clauses or the propensity to incur strategic underbidding and renegotiate later on. Chong et al. (2006) account for the endogeneity of organizational choices taken by local authorities on the performance of water services in France. They introduce a switching regressions model to account for the organizational choice of the local authority between direct public management and lease contracts. Their results show that local public authorities do not make their organizational choices randomly.

Gagnepain and Ivaldi (2017) build a structural model of political regulation, including social and private concerns that the regulator has when choosing a regulatory scheme. In their model, the regulator is not only concerned by social welfare, but is also incentivized by the possibility of being elected or re-elected. Therefore, it may account in its decision of contract type for the profit of the operator and/or the wage of operator’s workers. The operator’s choice of cost-reducing effort level conditional on the contract it faces is also described by the model.

Other empirical studies concentrate on the determinants of organizational choices, without assessing its impact on costs. For instance, Levin and Tadelis (2010) study the drivers of US city government privatization decisions, suggesting an important role played not only by economic efficiency concerns, but also by politics. Among others, they find that cities run by mayors are less likely to privatize services than cities run by appointed managers. Further, cities with higher ratios of long-term debt to revenue privatize more than those with lower levels of debt. In this respect, they argue that high debt levels constrain political opportunism and force city governments to focus on costs. State laws are shown to also affect the privatization decision. This is in line with the study of de Silanes et al. (1997), which shows state clean-government laws and state laws restricting county spending encourage privatization, while strong public unions discourage it. Finally, Duso (2005) focuses on the effects and determinants of price regulation on the US mobile phone industry and provides empirical evidence that the choice of regulatory regime strongly depends on political as well as regulatory environments.

The existing literature clearly suggests that contractual and organizational choices are not random. In our study, we assess the impact of contractual choices on cost efficiency by considering that regulatory choices are endogenously determined decisions. While a full welfare analysis is beyond the scope of this article, our findings allow us to assess whether the move toward fixed-price contracts observed in the industry is justified in order to recover efficiency. Furthermore, we are able to identify the determinants of regulatory choices and directly test the bias associated to treating contracts as randomly assigned.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the French urban public industry in France. In particular, the organizational background and the types of regulatory schemes observed in the industry are discussed. Section 3 introduces the theoretical motivation behind our empirical approach. Section 4 presents our empirical strategy, as well as the data and variables used. Section 5 then presents the estimation results of our empirical model. Section 6 concludes.

2 Industry background

2.1 Organizational background

The legal framework for urban public transport in France dates back to the Transport Law of 1982Footnote 1, which provided guidelines for public passenger transport in urban transport areas and established the concept of economic and social efficiency by providing the right to low-cost public transport. The institutional organization of public transport was then clarified by separating the functions of the organizer and operator for the relevant service. The local public authority (consisting of cities or groups of cities) became responsible for the organization of urban public transport by defining, financing, and organizing regular public passenger transport in the urban transport area.Footnote 2 It is now left the choice to organize and provide the service itself or to delegate the relevant responsibilities to a transport operator. In the latter case, a public-private partnership is established and regulated through an agreement. The decentralization acts of 1982Footnote 3 and 1983Footnote 4 aimed not just to share the responsibilities between the government and local communities, but also to strengthen the powers of local elected representatives. This widened the scope of the organizing authority.

Before 1993, the automatic renewal of contracts was a common practice (see Gagnepain and Ivaldi 2002a). The Sapin LawFootnote 5 made competitive bidding compulsory before awarding a contract for the provision of a public service. The aim of the law was to prevent collusion and corruption, thus enhancing competition between the operators in the industry. However, it did not forbid the use of negotiation in the procedure. As a result, operators can be selected in a two-step procedure, i.e. a preselection step with the use of competitive bidding and a negotiation phase, the latter allowing for subjective selection criteria.

The urban transport industry in France is highly subsidized. Currently, commercial receipts cover only around 28.5% of the operating costs of transport operators (see GART 2015). The rest is covered by subsidies coming from the state, local communities, as well as a special transport tax put on local businesses (fr. versement transport).Footnote 6

2.2 Transport groups

Between 1995 and 2010, nearly 70% of the operators were subsidiaries of three major groups, two of which are private and one semi-public: Keolis, Veolia Transport, and Transdev. In 2010, Keolis was 45% owned by SNCF, the French National Railway Company. Veolia Transport was a subsidiary of the French group, Veolia EnvironmentFootnote 7 and Transdev was majority owned (69.6%) by the French public financial institution, Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (hereafter CDC). These groups are present nationwide.

In addition, three smaller players were present in the market at that time. RATP Développement (hereafter, RATP Dev), owned by RATP,Footnote 8 was created in 2002. Vectalia France is a subsidiary of the Spanish group Subus and was present in France since 1998. The extent of the presence of Vectalia and CarPostal in France was mainly limited to transport areas close to the relevant boarders. In addition to the above, remaining operators were independent or belonged to local and regional transport groups.

2.3 Regulatory contracts

As provided by the French legal framework, the local public authority is responsible for defining the transport policy for the relevant urban area and organizing the provision of the relevant public services. At the same time, it can decide either to organize the services itself or to delegate this task to a fully private or public-private operator. About 90% of the transport networks in France are operated through delegated management (see GART 2015). In this case, the regulator chooses an operator to which it will entrust the operation of the service. A public-private partnership is then established and regulated through an agreement. The key feature of the French model is the attribution of the contract to only one operator who will carry the responsibility of providing the relevant service across the complete urban transport area. This agreement specifies the characteristics of the service, the operator’s obligations to the passengers, the terms and conditions of operator financing, payment, and fares, as well as the choice of regulation.

The choice of regulation translates into the division of risk-taking between the contracting parties. The basic trade-off concerns the choice between fixed-price and cost-plus contracts (see Laffont and Tirole 1993). These two types of contracts are observed in practice in the urban transport industry in France. In networks regulated under a fixed-price contract, operators receive subsidies according to their expected operating costs/deficits.Footnote 9 Therefore, any cost changes affect their profit. Companies subject to these arrangements face high-powered incentive schemes in terms of cost minimization behavior. On the other hand, in networks regulated by cost-plus contracts, the organizing authority collects commercial receipts and fully reimburses the operator’s operating costs, increased by a predefined additional amount. Under this regulatory scheme, the regulator provides the operator with subsidies to cover its actual deficits. This regulatory scheme is risk-free for the operator, as any cost changes do not affect his profit.

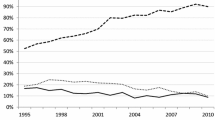

While the industry has gradually been shifting toward fixed-price contracts, no study relying on up-to-date data provides an assessment on whether the move toward fixed-price contracts observed in the industry is justified in order to recover efficiency.

3 Theoretical motivation

Considering the characteristics of the industry under study, we build on theoretical motivations and develop empirically testable propositions that will guide our analysis throughout the paper.

3.1 Asymmetric information

The theoretical assumption behind a cost function states that technical efficiency is achieved or, in other words, that firms minimize their costs given the level of output to be produced. However, there may be several reasons why this might not be true. Asymmetric information seems to play a crucial role in the industry under study.

In the case of delegated management, a regulator asks a transport operator to produce a given level of output in exchange for a reimbursement. This relationship is then regulated by a contract. The operator may have private information about its technology and may induce cost-reducing effort. In this framework, asymmetric information may give rise to two phenomena: adverse selection and moral hazard.

The organizing authorities in France face limited financial resources and specialized staff to perform a good audit or survey system.Footnote 10 On the other hand, as already mentioned, most of the operators belong to major groups that have not just experience from operating both in France and internationally, but also that perform research and development activities. Consequently, they have greater experience and information on the costs of providing the service than local authorities. This gives rise to the presence of adverse selection.

As in most transport networks, the local authority sets the pricing policy and finances the infrastructure. The operator can involve in cost-reducing actions exerted when providing the service. Given the complexity and limited data on the service, it becomes difficult for the local authority to assess the cost-reducing activities undertaken by the operator. The non-observability of the effort undertaken by the operator on the delegated operation of the transport service gives rise to a moral hazard problem.

Informational asymmetries between the regulator and the operator of the transport service may affect the production process. The operators of the service may undertake cost-reducing effort depending on the regulatory scheme put in place. In this setting, regulatory contracts chosen by the local authority could affect the input allocation and cost-reducing effort undertaken by the operator of the transport service.

The new theory of regulation considers informational asymmetries to be central in the contractual relationship between governments and firms. It adopts a normative approach to deal with these issues by assuming that regulatory contracts are optimally designed by regulators, who maximize social welfare through sophisticated mechanisms. When designing the regulatory policies in the presence of informational asymmetries, the government faces a trade-off between efficiency incentives typical for fixed-price contracts and rent extraction properties of a cost-plus contract (see Baron and Myerson 1982; Laffont and Tirole 1993).

Here, instead, we abstract from the problem of designing optimal regulatory contracts and take a positive approach assuming that the local government is unsophisticated. Accounting for the characteristics of the industry and assuming the presence of informational asymmetries in the contractual relationship, we assess the efficiency of the two contractual arrangements actually in place in the industry. Specifically, we investigate whether indeed fixed-price contracts provide more incentives for operators for cost-reducing activities. This can shed some light on the policy insights on whether the move toward fixed-price contracts occurring in the industry can be supported in view of efficiency arguments. The following proposition is tested:

Proposition 1

Networks regulated under fixed-price contracts are more cost efficient.

Assuming that informational asymmetries are at the core of the relationship between the government and the operator, we then consider contracts to be endogenously determined choices.

3.2 Regulatory capture

The characteristics of the industry suggest that organizational choices are not made by a benevolent government but, rather, may be driven by self-interest of parties involved in providing the service. Theoretically, this can be explained through the prism of regulatory capture.

Regulatory capture refers to a situation where regulatory decisions are made in favor of specific interest groups. This issue is closely related to the private interest theory of regulation (see Stigler 1971; Peltzman 1976; Becker 1983). The naive view of markets and regulation is to assume that the regulator is omniscient and benevolent. However, in practice, the regulator rarely has the will to implement effective regulation. From there, it does not necessarily pursue the goal of maximizing the public interest. Companies can seek to influence the choice of the regulator by adopting a strategic behavior of capture, e.g. corruption, collusion.

In the presence of informational asymmetries, regulated firms may extract rents and, therefore, may have the incentive to influence regulatory outcomes (see Laffont and Tirole 1991). Firms may be willing to affect the choice of regulatory contracts in their favor by providing incentives to the regulator. Public authorities may be willing to stay in power and, thus, may choose regulatory contracts favoring specific interest groups. Governments may be, for instance, interested in re-election and, thus, may be willing to undertake actions to maximize political support in favor of votes or campaign contributions in the next election. Others may wish to find jobs in the future in the industry that they are currently responsible for regulating (the “revolving door” phenomenon).

All these elements need to be accounted for when studying the strategic relations between a public authority responsible for organizing a public service and the company chosen to provide it. The characteristics of the industry seem to support this approach. The organizing authorities are politicians representing the municipal council and typically elected for a six year term. They may be interested in re-election and, thus, will undertake actions to maximize political support in the favor of votes or campaign contributions in the next election. Those who leave the government may attempt to find high-level jobs in the industry they were previously responsible for regulating. Operators belonging to major groups may want to maximize profits aggressively and, therefore, may have a preference for fixed-price contracts. These operators may be willing to affect the regulatory decision in favor of their preferred contract. The French model of regulation combines competitive tendering with negotiation. While firms are first pre-selected after a competitive bidding, there may be a second phase of negotiation. The procedure gives place for subjective selection criteria, including the choice of regulatory contract type. This will play an important role in regulatory relations between the local authority and the transport operator. Building on the arguments above, we introduce the following proposition to test in our empirical investigation:

Proposition 2

Operators belonging to major transport groups may influence the regulatory decision by favoring fixed-price over cost-plus contracts.

Contractual choices may further be explained by political considerations, such as the political ideology of the regulator. Specifically, the extent of risk-seeking of the regulator may differ depending on the political color of governments in power. A regulator may prefer to favor employees or rather shareholders according to his political color (see Pint 1991 or Roemer and Silvestre 1992). For instance, a right-wing regulator might prefer to propose a fixed-price contract to a private firm in order to capture part of its rent. As suggested by Gagnepain and Ivaldi (2017), right-wing governments may have a greater interest regarding profits and, therefore, may prefer to use fixed-price regimes. On the other hand, left-wing governments may care more about the wages of employees of the operator. They may be more likely to introduce low-powered incentive schemes putting less pressure on operating costs and allowing employees to extract higher wages. Building on these arguments, we set the following proposition:

Proposition 3

Right-wing governments, as compared to left-wing governments, may have a greater interest for profit, and therefore prefer to use fixed-price regimes over cost-plus regimes.

3.3 Political contestability

Another potential source of endogeneity of contractual choices may be political risk adaptation of local authorities facing challenges from political opponents and interest groups. Moszoro and Spiller (2019) and Beuve et al. (2019) argue that politics is vital in understanding public contracts. Local authorities responsible for providing a public service are politicians subject to political challenges stemming from the supervision and control by political opponents and interest groups. Specifically, political opponents may take actions in order to replace their opponent. Facing exogenous time constraints (elections) and fierce political competition, local authorities may want to increase contractual rigidity to prevent opportunistic behavior from their opponents. The latter may consist in the political opponent exposing or accusing the public manager of bad management with the purpose of replacing him. In the context of the industry studied, local governments’ contractual choices may be incentivized by the degree of competition faced from their opponents. Local authorities may increase the rigidity of a contract (opt for a fixed-price rather than cost-plus contract), the fiercer the electoral competition. We look at this question in our industry setting by empirically investigating the following proposition:

Proposition 4

In more monopolized political markets, regulators will opt for less rigid contracts (preference for cost-plus as opposed to fixed-price contracts).

3.4 Transaction costs

If the task to be performed by the company is complex, the regulatory contract signed by the principal and the agent describing the task to be performed by the agent can be expensive to write, to apply, and to renegotiate. Future contingencies can be difficult to predict. Unforeseen costs can occur. Transaction costs have their origins in contractual theories commenced by Coase (1937) and Williamson (1975). Transaction costs arise from the costs of seeking out buyers and sellers as well as arranging, policing, and enforcing agreements or contracts in a world of imperfect information (see Cowen and Parker 1997).

Contract enforcement requires the monitoring of the task performed. However, this may prove problematic for the organizing authority. The data collection needed may require costly studies. Thus, the regulator may content itself with the data provided by the operator and may decide not to involve itself in extensive data collection or careful monitoring. In the absence of reliable and complete data on the service provided, the enforcement of the regulatory contract will not be carried out efficiently.

As future contingencies may be difficult to predict at the moment the contract is designed, the regulatory contract is likely to be incomplete. As stated by Williamson (2002), “all complex contracts are unavoidably incomplete. For this reason, parties will be confronted with the need to adapt to unanticipated disturbances that arise by reason of gaps, errors and omissions in the original contract.” An agent may engage in opportunistic behavior ex ante in order to win the contract, by anticipating that it will be able to re-negotiate ex post terms not covered by the contract (see Prager 1990). Unforeseen costs related to the re-negotiation of the contract may occur.

Transactions costs may be an issue in the French transport industry. As pointed out by Yvrande-Billon (2006), a number of uncertainties may arise that make it hard for local authorities to commit not to change certain terms of contracts. Consequently, renegotiations may occur throughout the duration of the contract. As provided in Cour des Comptes (2005), contracts awarded for the performance of complex operations give rise to difficulties leading to additional costs during their execution.

In the presence of transaction costs, the choice of one contract over another (cost-plus versus fixed-price) may be dictated by the complexity of the project. Bajari and Tadelis (2001) consider ex post changes related to contract re-negotiations. They suggest the main problem the principal faces when delegating a task to an agent are in fact ex post re-negotiations. In line with this view, they develop a model that incorporates moral hazard and transaction costs related to contractual design and re-negotiations. Restricting their analysis to two types of contracts (fixed-price and cost-plus), they shed light on when each type of contract should be used. They show that complex tasks (more costly to design) will be accompanied by a high probability of ex post adaptations. These will be delegated using cost-plus contracts. On the other hand, simpler tasks (less costly to design) will be accompanied by a small probability of ex post adaptations. These are best administered using fixed-price contracts that provide cost-reducing incentives.

We test whether these findings hold in our industry setting and introduce the following proposition:

Proposition 5

Cost-plus contracts are preferred to fixed-price contracts when a network is more complex.

4 Empirical model

4.1 Empirical strategy

Our goal is to estimate the impact of regulatory contract choice on operators’ cost efficiency. Our empirical investigation begins by estimating a function of operating costs on a set of variables that shift costs, taking the following form:

where FP is the regulatory contract choice in place, \(\mathbf{X} \) is a vector of exogenous controls, and \(\alpha \) are network fixed effects. \(\beta \) and \(\xi \) are the parameters to be estimated, where the latter measures the shift in operating costs from cost-plus to fixed-price regimes within a network. Finally, \(\varepsilon \) is the stochastic error term.

An econometric problem arises when the contract type in place is endogenous. In order to obtain an unbiased estimate of the impact of regulatory choices on cost efficiency by accounting for the endogeneity of contract type, we introduce an endogenous treatment-regression model (see Heckman 1976; Maddala 1983; Greene 2012). Given that FP is an endogenous dummy variable, the empirical task is to use the observed variables to estimate the regression coefficients \(\beta \), while controlling for selection bias induced by non-random treatment assignment into regulatory regimes. Consequently, FP is introduced in the model expressed in Eq. 1 as a binary endogenous variable that is assumed to stem from an unobservable latent variable:

The value of FP is taken according to the rule:

\(\mathbf{Z} \) is a vector of variables that explain regulatory contract choices. The error terms (\(\varepsilon \),\(\eta \)) are assumed to be correlated bivariate normal with \(Var(\varepsilon )=\sigma ^{2}\), \(Var(\eta )=1\) and \(Cov(\varepsilon ,\eta )=\rho \sigma \).

4.1.1 Cost function

Our econometric strategy involves specifying an underlying cost function for urban transport services. We take an econometric approach to estimating frontiers that uses a parametric representation of technology, pioneered by Aigner et al. (1977) and Meeusen and den Broeck (1977). In particular, we use a fixed-effects methodology allowing the cost function to have a different intercept for different transport networks, exploiting the time-series properties of the data. In addition, we do not restrict cost changes to follow a particular time pattern for all firms (e.g. Schmidt and Sickles 1984; Cornwell et al. 1990; Kumbhakar 1990). Further, in contrast to other models (e.g. Kumbhakar et al. 1991; Battese and Coelli 1993) we do not make specific distributional assumptions for the composite error terms. Our approach is similar to that taken by Ng and Seabright (2001) in the study of the costs of providing air transport services.

Building on Equation 1, costs are modeled by the deterministic total cost function (giving the efficient level of costs) and a second term that reflects inefficiencies. Our hypothesis is that the second term can be broken down to (1) a term that varies across transport networks but is invariant across time and (2) a term that reflects changes in contractual choices, which can vary across networks and across time. Accordingly, we introduce the following cost function:

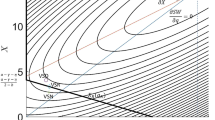

where C(.) is the deterministic cost function, \(Y_{it}\) is a vector of output, \(P_{it}\) represents a vector of input prices, and \(\alpha _{i}\) are firm specific shifts. Moreover, \(FP_{it}\) is introduced to capture the contract type under which a network is regulated at a given period. Finally, t is a time trend. \(\beta \), \(\alpha \), \(\xi \) are the parameters to be estimated. The subscript i (\(i=1,\ldots ,I\)) indexes the urban transport networks and t indexes time (\(t=1,\ldots ,T\)). We assume that operating costs can be represented by a restricted transcendental logarithmic cost function, defined by Christensen and Greene (1976).Footnote 11 For network i at time t, the cost function is the following:

where the normalization of operating costs \(C_{it}\), the price of labor \(PL_{it}\), and the price of overhead \(PO_{it}\) with respect to the price of materials \(PM_{it}\) imposes homogeneity of degree one in input prices.

4.1.2 Endogenous regulatory contract choices

Accounting for the endogeneity of contract type involves introducing in the model \(FP_{it}^{*}\) as a binary endogenous variable that is assumed to stem from an unobservable latent variable. For a given transport network i and time t:

where \(O_{it}\) reflects operators’ group and legal identity, \(P_{it}\) represents our political variables, \(N_{it}\) captures network complexity, and t is a time trend. Moreover, we include variables \(X_{it}\) determining costs from the previous Equation 5.

We next present the data and comment on the construction of variables that enter the model.

4.2 Data and variables

Our study uses a 16-year panel of 126 urban public transport networks in France between 1995 and 2010, with a total of 1,351 observations. The database was created from an annual survey conducted by the Centre d’études et d’expertise sur les risques, l’environement, la mobilité et l’aménagement (CEREMA) in collaboration with the Groupement des Autorités Responsables de Transport (GART) and the Union des Transports Publics et ferroviaires (UTP). For purposes of homogeneity across observations, only bus networks of more than 20,000 inhabitants throughout the whole period of analysis are studied in the analysis. As networks with a metro and tram system are excluded from the analysis, the biggest French cities (Paris, Lyon, Marseille, Toulouse, etc.) were not covered by our study. For the same reason overseas networks are excluded. Further, in order to include political variables when modeling contractual choices, the database was combined with the results of the municipal elections in France provided by the Centre de recherche politiques of Sciences Po (CEVIPOF, Paris, France). Finally, each observation in the database is treated as a realization of a regulatory contract choice for a given transport system in an urban transport network during a time period. In our database, contracts are signed for an average of 7-8 years. Consequently, we may observe several contract periods for each network. Our database covers a total of 339 contract periods.

Estimating the cost function requires information on operating costs, quantity of output and input prices. Operating costs C are defined as the sum of labor, material, and overhead costs. Output Y is measured by the number of seat-kilometers, i.e. the number of seats available in all buses multiplied by the number of kilometers traveled on all routes. Thus, we take a supply-oriented output variable, which accounts for both the size of the bus and the kilometers traveled. Labor price PL is obtained by dividing labor costs by the annual number of employees. Material price PM is obtained by dividing material costs by the number of buses. Overhead price PO is constructed by dividing overhead costs by the total number of registered trips. The local authority owns the rolling stock and infrastructure, which are put at the disposal of the operator. Since the operator does not own the capital, it does not incur capital costs. On the basis of the observed contractual choices, we build a binary variable representing the local authority’s choice of a fixed-price contract FP.

Descriptive statistics of our database are presented in Table 1Footnote 12. In our sample, average operating costs exceed 8M Euros per year. Yearly input prices amount to approximately 35,500 Euros per employee, 15,900 Euros per bus, and 500 Euros per trip. On average, more than 200M seat-kilometers are supplied per year. Finally, approximately 80% of all observations are fixed-price contracts.Footnote 13

Studying the determinants of regulatory contract choices requires data on the contract itself, the features of the network, as well as the characteristics of the actors involved in providing the service. The latter include, aside the local authority, the operators of the network. We construct dummy variables for operators belonging respectively to one of the three major transport groups present in the industry, i.e. Keolis, Veolia, Transdev. We take the legal status of the remaining operators into consideration by introducing a dummy variable \(Other-Priv\) for private companies, as opposed to private-public companies. Operators belonging to major transport groups may be willing to maximize profits aggressively and, hence, prefer fixed-price contracts.

Integrating information on the results of municipal elections in France in our database allows us to introduce two political variablesFootnote 14. The first is simply the political color of the mayor governing the main city responsible for organizing transport in a given urban area, distinguishing between right-wing (MayorR), diverse (MayorD), and left-wing (MayorL) political affiliation. As suggested by Gagnepain and Ivaldi (2017), right-wing governments may have a greater interest for profit, thus preferring to use fixed-price regimes. The second is a measure of political contestability \(NEP_{it}\), as introduced by Beuve et al. (2019), where the abbreviation refers to Number of Effective Parties. In particular, we compute the reciprocal of the Herfindahl-Hirschman index of the first round of the municipal elections through which the mayor responsible for network i at time t was chosen:

where \(P_{nit}\) is the share of votes of each party n in municipality i at time t during the first round of municipal elections before the signing of the contract. NEP below 2 corresponds to a single-party domination, whereas values above 2 suggests competition between two or more than two parties. The introduction of this variable may control for the concentration of the political scene. As proposed by Beuve et al. (2019), politically concentrated municipalities (lower NEP) may lead to less rigid contracts, which in our study would translate into choosing cost-plus over fixed-price contracts.

The organizational complexity of the service to be provided is captured by the number of communes comprising the transport network Communes. As suggested by Bajari and Tadelis (2001), in the presence of transaction costs, the choice of one contract type over the other may be dictated by the complexity of the project.

Summary statistics on variables used to explain regulatory contract choices are presented in Table 2. Respectively, 39%, 18%, and 27% of observations are networks operators belonging to Keolis, Transdev and Veolia. The remaining observations concern operators non-affiliated to any of those groups, which are either private (7% of our sample) or public-private companies. Regarding our political variables, 51% of observations concern networks governed by a right-wing mayor. In addition, average political contestability as measured by NEP amounts to 3. Finally, local authorities comprise between 1 and 115 communes, the average exceeding 13.

5 Results

In this section, we present and discuss the results of our analysis in light of the propositions set out in Sect. 3. We first show the results of estimating a cost function of urban transport operators. Specifically, Table 3 compares the output of a simple fixed-effects regression (column (1)) with the results of estimating an endogenous treatment effect model (columns (2)–(5)). For clarity of presentation, the results estimating the treatment equation are presented separately in Table 4.

As shown in Table 3, no matter the specification considered, we find that, ceteris paribus, a switch from a cost-plus to a fixed-price contract entails a significant reduction in operating costs. This result is in line with the theoretical prediction of new regulatory economics (and our Proposition 1 in Sect. 3) that fixed-price contracts provide more incentives for cost efficiency. However, the associated reduction is substantially higher when addressing the endogeneity of contractual choices: 21–23% as compared to 4%. Our results reveal the presence of bias if ignoring that contracts are not necessarily randomly assigned. The estimated correlation between the treatment-assignment errors and the outcome errors (\(Corr(\varepsilon ,\eta )\)) amounts to approximately 0.86-0.94, depending on the specification considered. This indicates that unobservables that raise operating costs tend to occur with unobservables that increase the choice of a fixed-price contract. The results of the Wald test of independent equations suggests that contract type is indeed an endogenous regressor. They also highlight the importance of accounting for the endogeneity of regulatory contract choices. Ignoring this aspect could lead to underestimating the impact of regulatory contract type on the cost efficiency of transport operators.

The remaining variables are of expected signs.Footnote 15 As all variables of the cost function were normalized to their sample mean value (except for time dummies, network-specific dummies, and contract type), the first-order coefficients can be interpreted as cost elasticities for an average transport network in the industry.

Table 4 presents the corresponding results of modeling contractual choices within our endogenous treatment effect model. Our economic, political and institutional drivers of regulatory choices are gradually introduced in the model. The corresponding marginal effects are presented in Table 5.

The results of modeling contract choice shed light on the relevance of elements advocated by the private-interest theory. Fixed-price contracts are more frequently observed when operators belong to one of the three major groups (Keolis, Veolia Transport or Transdev). As shown in Table 5, the probability to choose a fixed-price contract as opposed to a cost-plus contract increases significantly by, respectively, 0.20 and 0.19, when the operator belongs to, respectively, Transdev, and Keolis. As stated under our Proposition 2 in Sect. 3, operators belonging to major groups may be willing to maximize profits aggressively and, therefore, may attempt to affect the regulatory decision to choose a fixed-price contract. Our results seem to reflect this.

As regards to our political variables, a switch of the local authority from left-wing to right-wing increases the probability of choosing a fixed-price contract by 0.08. Following Proposition 3 in Sect. 3, right-wing governments may show a greater interest in profits, thus preferring to use fixed-price regimes.

Interestingly, an increase in political competition (as measured by our NEP variable) appears to be an important determinant of the choice of a fixed-price as opposed to a cost-plus contract. Our results are in line with Proposition 4 in Sect. 3 that in monopolized political markets (lower NEP), contracts are less rigid (preference for cost-plus as opposed to fixed-price contracts).

Further, our results suggest that complexity associated with managing a network (as measure by the number of communes composing a network) decreases the probability of choosing a fixed-price. Our results suggests that local authorities prefer to delegate the management of a complex project using cost–plus contracts. This result is in line with Proposition 5 in Sect. 3 that complex tasks (more costly to design) will be delegated using cost-plus contracts. On the other hand, simpler tasks (less costly to design) are best administered using fixed-price contracts that provide cost-reducing incentives.

In addition, our results clearly suggest that, with time, fixed-price contracts are more frequently chosen. A positive and significant sign of the parameter associated to the trend suggests a move toward high-powered incentive schemes.Footnote 16

6 Conclusion

In our paper, we directly test the bias associated to treating contracts as randomly assigned and identify the determinants of regulatory choices. We find a significant and important impact of regulatory choices on the costs of urban public transport industry in France. Given similar network characteristics, networks operated under a fixed-price contract experience approximately 21–23% lower costs than those regulated under cost-plus contracts. Ignoring the endogeneity of contractual choices, however, this effect is substantially lower and amounts to a reduction of approximately 4% of the total operating costs. Overall, our findings are in line with the theoretical prediction of new regulatory economics that fixed-price contracts provide more incentives for efficiency. Therefore, the move toward fixed-price contracts observed in the industry seems to be justified in order to recover efficiency.Footnote 17

Our results also shed light on the determinants of contractual choices. Fixed-price contracts are more frequently observed when operators belong to major groups. As these groups may be willing to maximize profits aggressively, they may attempt to affect the regulatory decision to choose a fixed-price contract. With regards to our political variables, a switch from left-wing to right-wing governments entails an increase in the probability of choosing a fixed-price rather than a cost-plus contract. This is in line with right-wing governments showing greater interest in profits, thus preferring to use fixed-price regimes. In addition, an increase in political contestability appears to be an important determinant for the choice of a fixed-price as opposed to a cost-plus contract, in line with the proposition that, in monopolized political markets, contracts are less rigid. Further, our result suggests that an increase in network size decreases the probability of choosing a fixed-price contract. This is in line with local authorities preferring to delegate the management of less complex projects/networks under fixed-price contracts and more complex ones under cost-plus regimes. Finally, our results show a move toward high-powered incentive schemes.

Most studies assessing the impact of regulatory regimes on cost efficiency of operators ignore the possibility that organizational or contractual choices are not necessarily made randomly. Using the example of the French transport industry, we show that comparing different regulatory designs without accounting for their endogeneity may lead to false conclusions in terms of their incentives for cost efficiency.

Notes

Loi n° 82-1153 du 30 décembre 1982 d’orientation des transports intérieurs.

Unlike the rest of France, the Ile-de-France region has only one authority responsible for organizing urban transport, namely “Syndicat des transports d’Ile-de-France (STIF)”. It is responsible for organizing, coordinating, and financing public transport on the behalf of the local authorities in this region. STIF takes its decisions in consultation with three transport carriers—RATP, SNCF, and OPTILE—compensating them for operating transport and the improvements they make at its request.

Loi n° 82-213 du 2 mars 1982 relative aux droits et libertés des communes, des départements et des régions.

Loi n° 83-8 du 7 janvier 1983 relative à la répartition de compétences entre les communes, les départements, les régions et l’Etat.

Loi n° 93-122 du 29 janvier 1993 relative à la prévention de la corruption et à la transparence de la vie économique et des procédures publique.

This tax is a local contribution of employers that allows to provide funding for the urban public transport. It was introduced in 1971 in Ile-de-France to meet operating and investment costs of urban transport networks. In its current form, it is imposed on both public and private sector employers with more than 9 employees within an urban transport area of a population of more than 10,000. In addition to the revenues from the sale of tickets and public subsidies, the transport allocation helps to cover the costs of urban public transport.

Veolia Environnement is an international group with activities in water provision, water sanitation, waste treatment, cleaning and sanitation services, energy services, and transport.

RATP is the operator of urban transport in Paris. It is a public company.

Within fixed-price contracts, two forms of contractual schemes can be further distinguished depending on the division of commercial risk between the private operator and local authority: gross-cost contracts and net-cost contracts. Under gross-cost contracts, the commercial risk is borne by the local authority. Local authorities collect commercial receipts and operators are reimbursed based on their expected operating costs. Under net-cost contracts, private operators carry both the industrial and commercial risk and are reimbursed based on their expected operating deficits. As the focus of the paper is on cost efficiency of the supply, we do not tackle the issue concerning informational asymmetries on the demand side and related incentive problem.

As stated in the 2015 report prepared by the French court of auditors (fr. Cour des Comptes) concerning, among others, the state of urban public transport in France, information provided by the operators to the local authority is often incomplete, erroneous, or non-explicit. This makes it difficult for the authority to analyze the effectiveness and efficiency of the management of the service delegated to the operator. Additionally, as underlined in the previous 2005 report of the French court of auditors, the control of the execution of the service undertaken by the organizing authorities and the means of expertise that they possess are still underdeveloped. The insufficiency of the reports provided by the operator to the organizing authority and the complexity of the organization of the service make the evaluation even more difficult. In addition, there are no national statistics measuring the structure and evolution of the population of passengers. This also concerns data allowing comparisons of the average consumption of their vehicles as compared to other networks.

In our empirical investigation, we perform a test to verify whether the transcendental logarithmic cost function is a good representation of the cost structure of transport operators in our study.

Please note that undertaking a robustness test by excluding the 1% top and bottom percentiles of each of the price variables, our results remain quantitatively and qualitatively largely similar to the baseline results.

Please note that we observe 29 switches of regulatory regime, with 85% concerning changes from a cost-plus to a fixed-price regime. Therefore, our results should be interpreted having in mind that predominantly switches from cost-plus to fixed-price contracts drive our estimation results.

In our analyses, we considered other political dimensions, including the role played by closeness to municipal elections or mayor’s tenure (see Coviello and Gagliaducci 2017). Our results suggest that these are not relevant dimensions in the industry studied. The results are available upon request.

In addition, in order to verify whether the transcendental logarithmic cost function gives a good representation of the cost structure of the transport operators in our sample, a likelihood-ratio test on the technology restrictions implied by a Cobb-Douglas functional form is performed. The results of this exercise lead to the rejection of these restrictions and, therefore, to retain the model presented in equation 6. The results are available upon request.

Please note that spatial dimensions do not seem to be relevant when considering regulatory contract choices in the French urban public transport. Urban transport networks are not directly neighboring and are dispersed geographically. Moreover, organizing transport authorities in France belong to an association of Transport Authorities (fr. Groupement des autorités responsables de transport). Through the association, they are aware of the contractual choices made by the remaining networks, independent of whether these are neighboring networks are not. Therefore, individual regulatory choices may rather be influenced by the general industry trends. This is in line with our results suggesting a positive trend on the choice of fixed-price rather than cost-plus contracts.

Please note that the contract governing the relationship between the local authority and transport operator specifies the characteristics of the service to be provided. This is, for instance, the case of quality.

References

Aigner, D., Lovell, C. K., & Schmidt, P. (1977). Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. Journal of Econometrics, 6(1), 21–37.

Bajari, P., & Tadelis, S. (2001). Incentives versus transaction costs: A theory of procurement contracts. The RAND Journal of Economicsl, 32, 387–407.

Baron, D. P., & Myerson, R. B. (1982). Regulating a monopolist with unknown costs. Econometrica, 50, 911–930.

Battese, G., & Coelli, T. (1993). A stochastic frontier production function incorporating a model for technical inefficiency effects. In Working papers in econometrics and applied statistics (Vol. 69).

Becker, G. (1983). A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence. The Quarterly Journal of Economic, 98, 371–400.

Beuve, J., Moszoro, M. W., & Saussier, S. (2019). Political contestability and contract rigidity: An analysis of procurement contracts. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 28(2), 316–335.

Chong, E., Huet, F., Saussier, S., & Steiner, F. (2006). Public-private partnerships and prices: Evidence from water distribution in France. Review of Industrial Organization, 29(1), 149–169.

Christensen, L. R., & Greene, W. H. (1976). Economies of scale in US electric power generation. Journal of political Economy, 84(4), 655–676.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

Cornwell, C., Schmidt, P., & Sickles, R. C. (1990). Production frontiers with cross-sectional and time-series variation in efficiency levels. Journal of Econometrics, 46, 185–200.

Cour des Comptes. (2005). Les transports publics urbains, Technical report.

Coviello, D., & Gagliaducci, S. (2017). Economic efficiency and political capture in public service contracts. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 9, 59–105.

Cowen, T., & Parker, D. (1997). Markets in the firm: A market-process approach to management. HOBART PAPERS (Book 134), Coronet Books Inc.

de Silanes, F. L., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Privatization in the United States. The RAND Journal of Economics, 28, 447–471.

Duso, T. (2005). Lobbying and regulation in a political economy: The U.S. cellular industry. Public Choice, 122, 251–276.

EC (03/10/2017). Increasing the impact of public investment through procurement—factsheet.

Gagnepain, P., & Ivaldi, M. (2002a). Incentive regulatory policies: The case of public transit systems in France. The RAND Journal of Economics, 33, 605–629.

Gagnepain, P., & Ivaldi, M. (2002b). Stochastic frontiers and asymmetric information models. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 18(2), 145–159.

Gagnepain, P., & Ivaldi, M. (2017). Economic efficiency and political capture in public service contracts. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 65, 1–38.

GART. (2015). L’année 2013 des transports urbains.

Gautier, A., & Yvrande-Billon, A. (2013). Contract renewal as an incentive device (p. 4). Review of Economics and Institutions: An Application to the French Urban Public Transport Sector.

Greene, W. (2012). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Guasch, J., Laffont, J., & Straub, S. (2007). Concessions of infrastructure in Latin America: Government-led renegotiation. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22, 1267–1294.

Heckman, J. (1976). The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, 5, 475–492.

Kumbhakar, S. C. (1990). Production frontiers and panel data, and time-varying technical inefficiency. Journal of Econometrics, 46, 201–211.

Kumbhakar, S., Ghosh, S., & McGuckin, J. (1991). A generalized production frontier approach for estimating determinants of inefficiency in U.S. dairy farms. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 9(3), 279–286.

Laffont, J.-J., & Tirole, J. (1991). The politics of government decision-making: A theory of regulatory capture. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 1089–1127.

Laffont, J., & Tirole, J. (1993). A theory of incentives in procurement and regulation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Levin, J., & Tadelis, S. (2010). Contracting for government services: Theory and evidence from U.S. cities. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 58, 507–541.

Maddala, G. (1983). Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meeusen, W., & den Broeck, J. V. (1977). Efficiency estimation from cobb-douglas production functions with composed error. International Economic Review, 18(2), 435–444.

Moszoro, M. W., & Spiller, P. T. (2019). Political contestability and public contracting. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 21, 945–966.

Ng, C. K., & Seabright, P. (2001). Competition, privatisation and productive efficiency: Evidence from the airline industry. The Economic Journal, 111(473), 591–619.

Peltzman, S. (1976). Toward a more general theory of regulation. The Journal of Law & Economics, 19(2), 211–240.

Piacenza, M. (2006). Regulatory contracts and cost efficiency: Stochastic frontier evidence from the italian local public transport. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 25, 257–277.

Pint, E. M. (1991). Nationalization vs. regulation of monopolies: The effects of ownership on efficiency. Journal of Public Economics, 44(2), 131–164.

Prager, R. (1990). Firms behavior in Franchise monopoly markets. The RAND Journal of Economics, 21, 211–225.

Roemer, J. E., & Silvestre, J. (1992). A welfare comparison of private and public monopoly. Journal of Public Economics, 48(1), 67–81.

Schmidt, P., & Sickles, R. (1984). Production frontiers and panel data. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 2(4), 367–374.

Stigler, G. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

Williamson, O.E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies (vol. 2630). New York

Williamson, O. (2002). The theory of the firm as governance structure: From choice to contract. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16, 171–195.

Yvrande-Billon, A. (2006). The attribution process of delegation contracts in the french urban transport sector: Why competitive tendering is a myth. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 77(4), 453–478.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are extremely thankful to CEREMA, GART, and UTP for providing the complete database on urban public transport in France for the purpose of our research. We thank Özlem Bedre-Defolie, Tomaso Duso, Matthias Finger, Emmanuel Frot, Philippe Gagnepain, Marc Ivaldi and Stéphane Saussier, as well as audiences at conferences at EARIE, ESNIE, and the EUI conference on the Regulation of Infrastructures and two anonymous referees for their valuable comments.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piechucka, J. Cost efficiency and endogenous regulatory choices: evidence from the transport industry in France. J Regul Econ 59, 25–46 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-020-09423-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-020-09423-y