Abstract

Prior to the subprime crisis, mortgage brokers charged higher fees for subprime loans that turned out to be riskier ex post, even when conditioning on other risk characteristics. Borrowers who paid higher conditional fees were inherently more risky, not just because they paid higher fees. The association between conditional fees and delinquency risk was stronger for purchase rather than refinance loans, and for loans originated by brokers who had less frequent interactions with the lender. This work sheds light on how regulation that limits origination charges to a fixed fraction of the loan amount may impact mortgage lending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Prior to the subprime crisis that began in 2007, the majority of subprime loans were originated by mortgage brokers.Footnote 1 Mortgage brokers are financial intermediaries who match borrowers with lenders, and are compensated for their services at the time the loan is funded. Using data from, formerly, one of the largest subprime lenders, New Century Financial Corporation, we explore the loan-level link between broker revenues and mortgage credit risk.

Based on a simple model of the origination process in the wholesale mortgage market, we hypothesize that there is a positive association between broker revenues and mortgage credit risk. The model suggests that this association arises whenever there are borrower attributes associated with mortgage credit risk that are not fully reflected in the lender’s pricing of the loan. Consistent with Pavlov and Wachter (2009) and Levitin et al. (2020), borrowers whose loans are more underpriced for risk—such as borrowers who inflate their credit worthiness on the loan application or have negative private information about their delinquency risk—have a greater incentive to pay their broker and take advantage of the underpriced loan.

We test our hypothesis that broker revenues are positively related to future payment delinquency using data for all broker-originated loans funded by New Century between 1997 and 2006. We measure broker revenues as a percentage of the loan amount and define mortgage credit risk as the risk of borrowers becoming delinquent on their mortgage payments. For brokered New Century loans, average 12-month delinquency rates are higher when broker revenues are higher—increasing from 10% for loans with percentage revenues of 1-2% to 19% for loans with percentage revenues of more than 5%.

This unconditional link between broker revenues and mortgage credit risk may arise because revenues proxy for other risk characteristics. To quantify the marginal information content of broker revenues for future payment delinquency, we condition on the information available to New Century at the time the funding decision is made. This information encompasses a wide range of loan, property, borrower and broker characteristics—it includes the mortgage rate but excludes information available only to the borrower and the broker. We provide comprehensive evidence that high conditional broker revenues reflect high mortgage credit risk. Based on a proportional odds duration model for the probability of first-time delinquency, we find that a marginal increase in percentage broker revenues by 1% is associated with a 6.4% higher odds ratio.

During our sample period, mortgage broker compensation has two distinct components—a direct fee charged to the borrower and a yield spread premium (YSP) paid by the lender. The YSP is based on loan and borrower characteristics and, all else the same, higher mortgage rates produce higher YSP payments (Jackson and Burlingame 2007).Footnote 2 Given that YSP is part of the lender’s information set, for a given lender and point in time, YSP should provide no additional predictive power for mortgage credit risk. Our analysis confirms that the marginal predictive power of broker revenues for delinquency risk does indeed stem from the direct fee component and not from the YSP component. A marginal increase in percentage fees by 1% is associated with a 7.6% higher odds ratio of first-time delinquency, and a one standard deviation increase in conditional percentage fees is associated with a 8.0% higher odds ratio. We present evidence that borrowers who pay high conditional fees are inherently more risky, not just because paying a higher fee at origination leaves them more cash constrained.

We show that the association between conditional fees and delinquency risk is stronger when there are greater information asymmetries between the borrower and the lender, and when the broker has fewer incentives to transmit precise information to the lender. First, we observe that lenders are likely to have more housing-related information about borrowers who refinance an existing loan than about borrowers who purchase a home for the first time. We also document that borrowers who refinance an existing mortgage tend to have more money invested in the home than borrowers who purchase a home, and thus may be less heterogeneous in their attitude towards delinquency risk and valuation of the put option embedded in non-recourse loans. We therefore postulate that there are greater information asymmetries between the borrower and the lender for purchase than refinance loans, and show that conditional fees are more informative about delinquency risk for purchase loans than for refinance loans.

Second, we document a weaker association between conditional fees and delinquency risk for loans originated by relationship brokers as opposed to non-relationship brokers. Relationship brokers are brokers who have frequent interactions with the lender. Relationship brokers may value their relationship with the lender more than non-relationship brokers, and thus may transmit more precise information to the lender regarding the borrower’s ability to repay the loan.

One caveat of our work is that it uses data from only one lender. Additional analysis shows, however, that New Century’s loan pool is largely representative of the broader subprime market. Moreover, our main finding that high conditional broker fees predict high mortgage credit risk is supported by several data-focused robustness checks.

While not the focus of this paper, our results do speak to the potential impact of regulation that limits mortgage broker compensation to a certain fraction of the loan amount.Footnote 3 For the loans in our data, we decompose broker revenues into costs and profits. Broker costs are the costs that the broker expects to incur between the time they strike a deal with the borrower and the time the loan is funded. Brokers originate a loan only if revenues cover costs. We show that for a wide range of assumptions underlying the estimation of broker costs, average percentage costs are larger for smaller loans. This is consistent with sizable fixed costs associated with loan origination. Small loans, however, are often taken out by low income, low credit quality borrowers, and are generally riskier than large loans. As a result, limiting broker revenues to a fixed percentage of the loan amount is likely to constraint the origination of smaller—and unconditionally riskier—loans. Limits on percentage broker revenues are less likely to impose any constraints on larger loans, and do not exploit the conditional link between high broker revenues and high mortgage credit risk.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section “Related Literature” previews prior related work. Section “Hypothesis Development” develops our hypotheses about the association between broker origination charges and mortgage credit risk. Section “Data and Descriptive Statistics” describes the data and “Empirical Results” investigate whether the data support the posted hypotheses. Section “Robustness Checks and Extensions” implements a number of robustness checks and “Conclusion” concludes.

Related Literature

The focus of our study is the link between broker compensation and delinquency risk in the subprime mortgage market. The level and determinants of broker compensation have been analyzed by Woodward (2003, 2012); Garmaise (2009); Reuters (2011), among others. Prior studies such as Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) and Jiang et al. (2014) relate mortgage credit risk to loan, property and borrower characteristics. But, due to a lack of data, these papers do not control for loan originator compensation. An exception is Garmaise (2009) who takes an in-depth look at broker-lender relationships for prime loans. The median borrower in his sample, however, does not pay any direct broker fees, thereby making it difficult to establish a link between broker charges and delinquency risk.

To predict borrowers’ delinquency risk, researchers tend to apply a duration model methodology such as the Cox proportional hazard model used in Deng (1997) and Ambrose and Capone (2000) and (Deng and Quigley 2000).Footnote 4 Proportional hazard models are appealing not only because they allow for flexible default patterns over time but also because they offer a convenient way to incorporate censored observations.Footnote 5 An alternative approach is to estimate a probit model as in (Danis and Pennington-Cross 2005; Gerardi et al. 2010) and (Jiang et al. 2014). While duration models capture the time between loan origination and credit event, probit models do not distinguish between mortgages that become delinquent at different points in time. In this paper, we employ a proportional odds duration model, the discrete-time analogue to the Cox proportional hazard model.

Our finding that riskier borrowers pay higher broker charges is consistent with the work by Pavlov and Wachter (2009) and Levitin et al. (2020), who show that during our sample period the put option embedded in non-recourse subprime loans was often underpriced and that the put option became more valuable as the borrower’s inherent risk increased. In that sense, riskier borrowers had a greater incentive to pay the broker because it was in their interest to take advantage of loans that were more underpriced for risk. Our hypothesis that the association between broker fees and delinquency risk is stronger when there are greater information asymmetries between the borrower and lender connects our work to the broader literature on lenders’ imperfect information and borrowers’ access to credit that goes back to the seminal work by Stiglitz and Weiss (1981).

While our analysis identifies direct fees as the broker revenue component with the larger information content for delinquency risk, a number of studies have analyzed YSP payments and discussed the pros and cons of this indirect form of broker compensation (Woodward 2003, 2012; Hong and Reza 2005; LaCour-Little 2009; Ambrose and Conklin 2014). Critics charge that YSP payments increase the overall cost of broker loans and violate the anti-kickback provisions of the 1974 Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act, while others counter that YSP is a legitimate form of compensation that allows cash-strapped borrowers to finance closing costs through higher future mortgage payments (Jackson and Burlingame 2007). In an effort to stop brokers from originating loans at higher-than-prevailing mortgage rates, and to protect borrowers from unfair practices, the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation Z introduced loan originator compensation rules that went in effect April 1, 2011.Footnote 6 These rules prohibit mortgage broker compensation to vary based on loan terms, other than principal, meaning brokers can no longer receive YSP payments from the lender. Our results suggest that even in the absence of YSP payments, broker compensation may contain information about otherwise unpriced mortgage credit risk.

Our discussion of the potential impact of limiting broker compensation in an effort to reduce origination of high risk loans relates to the broader literature on access to mortgage credit markets (Heuson et al. 2001; Courchane et al. 2004; McCoy 2017).

Hypothesis Development

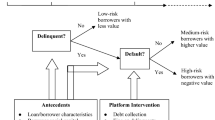

In this section, we present our hypotheses about the association between broker origination charges and mortgage credit risk. There are several channels through which broker charges and mortgage credit risk may be linked. To streamline our discussion, we base it on a simple model of the origination process in the wholesale mortgage market, where independent mortgage brokers act as financial intermediaries matching borrowers with lenders. The model is developed in Appendix A and implies that borrowers who shop from fewer brokers tend to pay higher broker charges; that among borrowers who do not shop around those with a higher valuation for the loan pay higher broker charges; and that among borrowers who shop from multiple brokers those for whom brokers perceive costs to be higher pay higher broker charges.

The model’s implications are conditional on the information available to the lender at the time the funding decision is made. The lender’s information set, denoted by \(\mathcal I\), includes the borrower, property and loan characteristics—including the mortgage rate—that are passed on by the broker to the lender. The borrower may, or may not, be truthful when providing information to the broker.Footnote 7 Even when truthful, the borrower may be privy to additional information that is not included in \(\mathcal I\). We refer to a truthful borrower without any private information as a benchmark borrower.

Conditional on \(\mathcal I\), we contrast benchmark borrowers with riskier non-benchmark borrowers that inflate their credit worthiness on the loan application or have negative private information about their delinquency risk. To keep things simple, we assume that by interacting with the borrower during the origination process the broker learns whether or not the borrower is truthful and observes the borrower’s private information, if any.Footnote 8 The broker may use such soft information to discourage riskier borrowers from shopping from additional brokers, which would result in riskier borrowers paying higher broker charges than benchmark borrowers. Alternatively, the broker may assign a higher cost to serving riskier borrowers to compensate for the potential loss of reputation with the lender. If borrowers were to shop from multiple brokers, the model in Appendix A would imply that broker revenues equal the cost of the second-lowest-cost broker, and thus are higher for riskier borrowers.

If borrowers were to shop from only one broker,Footnote 9 the broker’s revenue would be a function of borrower’s valuation for the loan.Footnote 10 Riskier borrowers know that their income, access to credit or level of consumption may be limited in future periods compared to that of benchmark borrowers, either because they lie about their future earning power and expenses, or because they know they are more exposed to negative future shocks. Thus, riskier borrowers would perceive future discount factors to be higher, and value future net benefits from living in the home more, than benchmark borrowers.Footnote 11 As a result, riskier borrowers would pay higher broker charges.

In summary, we hypothesize that information asymmetries where the borrower knows more about their risk than the lender result in higher broker revenues for loans that turn out to be riskier ex post.

Hypothesis 1

Conditional on \(\mathcal I\), higher broker revenues are associated with higher mortgage credit risk.

The notion that riskier borrowers tend to pay higher broker charges is consistent with the work by Pavlov and Wachter (2009) and Levitin et al. (2020), who show that during housing market bubbles (such as the one during our sample period) the put option embedded in non-recourse subprime loansFootnote 12 tends to be underpriced and that mortgage rates do not adequately compensate for the put option. The underpricing of subprime non-recourse loans tends to increase, and the put option tends to become more valuable, as the borrower’s inherent risk increases. In that sense, riskier borrowers have a greater incentive than benchmark borrowers to pay the broker because it is in their interest to take advantage of loans that are more underpriced for risk.

A further, behavioral argument in support of Hypothesis 1 is based on the notion of over-optimism. For this argument, we refer to benchmark borrowers as borrowers with objective expectations about the joint conditional distribution of the variables determining the borrower’s loan valuation (see Eqs. 7 and 8). Conditional on \(\mathcal I\), we contrast benchmark borrowers with borrowers that are overly optimistic. Motivated by the findings in Dawson and Henley (2012), we conjecture that overly optimistic borrowers tend to be inherently more risky. The broker observes over-optimism and may exploit it by discouraging over-optimistic borrowers from shopping from additional brokers. Alternatively, the broker may assign a higher cost to serving over-optimistic borrowers to compensate for the potential loss of reputation with the lender due to originating riskier loans. Because of over-optimism, non-benchmark borrowers may underestimate future mortgage payments, overestimate the time until default, underestimate the costs associated with mortgage default, or underestimate the net payments associated with refinancing the loan or selling the home in the future. In each of these cases, the over-optimistic borrower’s valuation for the loan will be higher than that of a benchmark borrower. Thus, within the framework of Appendix A, overly optimistic borrowers—who we conjecture to be riskier—tend to pay higher broker charges.

Finally, we consider the link between each of the two broker revenue components—fees and YSP—and delinquency risk. Our inspection of so-called “rate sheets” provided by lenders to brokers suggests that lenders set YSP as a function of loan and borrower characteristics, such as the loan type, loan amount, documentation level, borrower credit history and mortgage rate. While the function that translates loan and borrower characteristics into YSP may differ across lenders and over time, for a given lender and point in time, we expect conditional heterogeneity in YSP to be limited. Thus, the following is consistent with Hypothesis 1:

Hypothesis 2

Conditional on \(\mathcal I\), there is a positive association between broker fees and mortgage credit risk. For a given lender and point in time, YSP has no additional predictive power for mortgage credit risk.

In what follows, we describe the data and investigate whether they support the posted hypotheses.

Data and Descriptive Statistics

Our main dataset is obtained from IPRecovery, Inc. and contains detailed records of all loans originated by New Century. New Century made its first loan to a borrower in Los Angeles in 1996 and subsequently grew into one of the top three U.S. subprime lenders. It originated, retained, sold and serviced residential mortgages primarily targeting subprime borrowers. An increase in early delinquencies in late 2006 and early 2007, together with inadequate reserves for such losses, led to New Century’s bankruptcy filing on April 2, 2007.

New Century’s origination volume grew from less than 1 billion in 1997 to almost 60 billion in 2006. The explosive growth in volume was largely fueled by independent mortgage broker activity. Between 1997 and 2006, over 70% of all New Century loans were originated through the broker channel. This is consistent with the pattern observed for the broader subprime market, where prior to the subprime crisis mortgage brokers had become the predominant channel for loan origination. For example, as of 2005 mortgage brokers originated about 71% of all subprime loans.Footnote 13 Focusing on broker-originated loans allows us to abstract from differences in the compensation structure of brokers and loan officers, while still capturing the vast majority of New Century’s business. Appendix B describes the steps we take to clean the raw New Century data, and Table 1 lists the variables used in our empirical analysis.

Origination Data and Loan Performance

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for the broker-originated loans funded by New Century between 1997 and 2006. The number of loans in our sample grew exponentially, from about 3,000 loans originated in 1997 to 143,000 in 2006. Piggyback loans became popular from 2004 onwards. The average size of loans grew from about 100K in 1997 to more than 200K in 2006, with higher average amounts for piggybacks. The number of brokers used by New Century in any given year grew dramatically, from about 900 in 1997 to 26,000 in 2006. Over the sample period, about 669,000 loans were originated by 56,000 independent brokers with an average size of 190K.

Our sample represents subprime loans from all parts of the country, with California, Florida and Texas being the three biggest markets. About 90% of all loans were originated in metropolitan areas. Approximately two-thirds of the loans were taken out to refinance existing loans, and the majority of the refinance mortgages involved cash-out payments to the borrower. For the whole sample period, hybrid loans were the most common ones followed by fixed-rate loans. In 2005–2006, loans with balloon and interest-only payments became more popular, reaching 54% of the loans in 2006. For most of the sample period, the 2/28 hybrid dominated the hybrid category and the 30-year fixed-rate loan the fixed-rate category. The majority of loans came with a product-specific prepayment penalty.

Like other subprime lenders, New Century had three levels of income documentation: full, limited and stated. For a full documentation loan, the applicant was required to submit two written forms of income verification showing stable income for at least twelve months. With limited documentation, the prospective borrower was generally required to submit six months of bank statements. For stated documentation loans, verification of the amount of monthly income the applicant stated on the loan application was not required. The fraction of limited and stated documentation loans varied between 33% in 1997 and 47% in 2004.

The majority of the loans were for single-family homes that served as the borrower’s primary residence. The average borrower FICO score fell by almost 30 points between 1997 and 2001, before rising again by roughly the same amount during the second half of the sample. Piggyback loans were made to borrowers with relatively high credit scores, but presumably no cash savings. The borrowers who took out low documentation loans usually had higher credit scores than those that provided full documentation. Even though the average combined monthly income rose from 5.4K in 1997 to 7.2K in 2006, debt-to-income ratios increased slightly, from 37% in 1997 to 41% in 2006. Loan amounts grew not only relative to income levels, but also relative to property values. LTV ratios rose from 73% in 1997 to 80% later in the sample, as second liens gained in popularity.

From 1999 onwards, the IPRecovery data contain detailed servicing records for most of the New Century loans. For every year from 1999 to 2006, more than 99% of the funded broker loans are part of the servicing data, except for 2001 (83%) and 2002 (42%). As in Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) and Jiang et al. (2014), we consider a loan to be delinquent if payments are 60 days or more late, or if the loan is in foreclosure, real estate owned or in default. For each year of origination k, let \(\widehat {p^{k}_{s}}\) denote the number of vintage-k loans experiencing a first-time delinquency s months after origination, divided by the number of vintage-k loans that are still active after s months or experience a first-time delinquency at age s. The cumulative delinquency rate of vintage-k loans at age t is

Figure 1 plots \(\widehat {P^{k}_{t}}\) as a function of the age of the loan t and vintage k. The results in “Empirical Results” show that after controlling for year-by-year variation in loan-level characteristics, loans originated in 2004 and 2005 were riskier than loans originated earlier in the sample.

Delinquency Rates The figure shows the fraction of loans delinquent as a function of months from origination, by year of origination. The delinquency rate is defined as the cumulative fraction of loans that are past due 60 days or more, in foreclosure, real-estate owned or defaulted, at or before a given age

Broker Charges

During our sample period, independent mortgage brokers earned revenues from two sources: a direct fee paid by the borrower and an indirect fee—the YSP—paid by the lender. Direct fees include all compensation associated with the mortgage transaction paid by the borrower directly to the broker, including finance charges such as appraisal and credit report fees. The YSP rewards the broker for originating loans with higher mortgage rates, holding other things equal. Table 3 shows that total broker revenues per loan, as a percentage of loan amount, declined steadily from 4.9% in 1997 to 2.8% in 2006. The decline in percentage revenues was almost equally split between a decline in fees and in YSP. Dollar revenues per loan, on the other hand, increased over time from 4.2K in 1997 to 5.6K in 2006. The increase in dollar revenues corresponds to an annual compound rate of 3.3% which is similar to the rate of inflation. The decrease in percentage revenues and the relatively modest growth in dollar revenues may reflect an increase in broker competition over time.

The top panel in Fig. 2 shows the unconditional distribution of broker revenues and its two components.Footnote 14 All three distributions are disperse and skewed to the right: some very large fees and yield spread premia were paid out to brokers. The right skewness in the revenue distribution appears to be a robust feature across different strata of our sample, as documented in the remaining panels in Fig. 2, although the skewness is smaller after conditioning on the loan amount.

The first column in the bottom panel of Table 3 reveals that brokers are generally rewarded more for originating larger loans. While brokers earn an average 2.2K per loan for mortgages of 50K or less, they earn 9.7K for loans in excess of 500K. In Appendix C, we decompose broker revenues into costs and profits, and show that borrowers who took out larger loans paid substantially higher dollar margins above costs than borrowers who took out smaller loans. Both direct fees and YSP contribute to the increase in revenues as loan amount increases. After controlling for the size of the loan, there is much less variation in revenues. Nevertheless, hybrid loans usually generate lower broker revenues than fixed-rate, balloon and interest-only loans. Borrowers with a lower FICO score often pay higher broker charges compared to higher-credit-quality borrowers. Loans with a prepayment penalty generally yield higher broker revenues, mainly due to higher fees.

While variables such as loan size, loan type and borrower FICO score predict broker revenues, we find substantial variation in revenues even after conditioning on the entire set of variables in Table 1. Table 4 shows that conditioning variables explain 50.7% of the variation in dollar revenues and 41.9% of the variation in percentage revenues. The fraction of variation explained is lower for broker fees than revenues. Only 40.5% of the variation in dollar fees and 37.8% of the variation in percentage fees can be explained by the conditioning variables in Table 1. Much of the explained variation in broker fees is explained by the loan amount which, by itself, yields an R2 of 26.7% for dollar fees and 22.1% for percentage fees. Controlling for YSP in addition to loan amount increases the R2 for dollar and percentage fees to 32.4% and 25.4%, respectively. A marginal increase in YSP is only partially offset by lower fees, consistent with Woodward (2003). Residual fees are skewed to the right, with a skewness coefficient of 0.50 for dollar fees and 0.53 for percentage fees, indicating that a sizable fraction of borrowers pay high conditional fees.

During our sample period, almost 56,000 different brokerage firms do business with New Century. Each company consists of one or more individuals working out of the same office. The median brokerage firm has only sporadic contact with New Century, and originates about four loans or 734K for this lender between 1997 and 2006. The top three loan originators in our sample are Worth Funding (9,705 loans), United Vision Financial (2,826 loans) and Dana Capital Group (1,446 loans). Our results are robust to excluding loans originated by these three brokerage firms from the data.

A Comparison to the Broader Subprime Market

Prior to its collapse, New Century was one of the largest U.S. subprime lenders. Below, we compare the characteristics of New Century’s loan pool to those for the broader subprime market. Loan origination and performance statistics for the broader subprime market are reported by Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011), who base their analysis on First American CoreLogic LoanPerformance (LP) data from 2001 to 2006. The LP dataset contains loan-level origination and servicing records for roughly 85% of all securitized subprime mortgages and offers the widest coverage of subprime loans available.Footnote 15 One drawback of the LP data is that they do not identify broker loans nor do they include broker charges. Nevertheless, in Table 5 we use the LP data as a benchmark to compare New Century’s loan pool to the broader subprime market.

In the LP data, the average loan size increased from 126K in 2001 to 212K in 2006, compared to an increase from 149K to 217K over the same time period in the New Century sample. The percentage of fixed-rate, balloon and hybrid mortgages ranged from 33%, 7% and 60% in 2001 to 20%, 25% and 55% in 2006 in the LP data, and from 19%, 0% and 81% to 14%, 40% and 46% in our data.Footnote 16 In the LP data, the average FICO score for first-lien loans rose from a low of 601 in 2001 to a high of 621 in 2005; in our sample it increased from 585 to 622 over the same time period. Average combined loan-to-value ratios are in almost perfect alignment between our and the LP data, ranging from just below 80% in 2001 to 86% in 2006. Debt-to-income ratios are fairly flat and around 40% in both samples. The distribution of the loan purpose for New Century loans is similar to that reported for the LP data as are mortgage rates (not reported). Rate margins and fractions of loans with prepayment penalties are also quite closely aligned for both samples.

The share of loans with full documentation fell from 77% in 2001 to 62% in 2006 in the LP data, but stayed fairly flat at around 55% in the New Century data. If we were to combine full and limited documentation loans in the New Century data, the fraction of such loans would have declined from 64% in 2001 to 60% in 2006. Overall, the origination statistics for the New Century loans in our sample are in line with those for the broader subprime market.

A report by Moody’s (2005) shows that the performance of New Century loans closely tracked that of the subprime industry. We confirm this finding by comparing the cumulative delinquency rates for our data, as shown in Fig. 1, with those reported by Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) for the LP data. For the LP (New Century) data, 12-month cumulative delinquency rates are 13% (20%), 9% (13.5%), 7.5% (8.5%), 9% (10%) and 12% (13%) for loans originated in 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2005, respectively. These delinquency statistics are rather similar, especially for the latter part of the sample. The only two years with larger differences in delinquency rates are 2001 and 2002, precisely the years in which a sizable portion of the New Century loans are missing from the servicing data. Given the lack of data, we put less weight on the 2001 and 2002 estimates and verify that our empirical findings are robust to excluding loans originated prior to 2003. The 2003-2005 delinquency rates reported for the LP data are about 1% lower than those for our sample perhaps because the LP data include retail loans in addition to broker loans. Jiang et al. (2014) find that retail loans are generally safer than broker loans.

While the LP data does not contain information on broker charges, two related studies report data on broker fees and YSP. Woodward and Hall (2012) analyze about 1,500 FHA fixed-rate loans originated during a six-week period in 2001 and report average broker revenues of about 4.1K per loan and an average loan size of about 113K. In percentage terms this is comparable to the 2001 statistics we report in Tables 2 and 3, although our dollar values are somewhat higher both for revenues (4.8K) and loan size (149K). Garmaise (2009) studies a sample of almost 24,000 residential single-family mortgages originated between 2004 and 2008. He reports average percentage broker revenues of 2.1%. Neither study, however, focuses on subprime loans. A 2011 news release by 360 Mortgage Group on mortgage broker compensation states that brokers generate an average revenue of 2.25% per loan (Reuters 2011).Footnote 17 This figure is consistent with the compensation statistics reported in Table 3 and points to a continued decline in percentage revenues beyond 2006.

In summary, New Century’s loan pool is largely representative of the broader subprime market. Following its bankruptcy filing in 2007, New Century received widespread attention in the popular press, mainly because it was the largest subprime lender to default by that date. By 2009, however, virtually all of New Century’s main competitors had either declared bankruptcy, had been absorbed into other lenders, or had otherwise unwound their lending activities.Footnote 18

The Unconditional Link Between Broker Charges and Mortgage Credit Risk

The left panel in Fig. 3 shows average 12-month delinquency rates for loans sorted by percentage broker revenues. Delinquency rates are lowest—about 10%—for loans with percentage revenues of 1-2%. They increase steadily as percentage revenues increase, and peak at over 19% for loans with percentage revenues of more than 5%. The average 12-month delinquency rate for loans with percentage revenues of less than 1% is slightly higher than that for loans with 1-2% revenues, consistent with somewhat higher delinquency rates among very large, low percentage revenue loans and also consistent with some extremely cash constrained borrowers obtaining small-cost loans. Overall, however, loans with high percentage revenues are riskier than loans with low percentage revenues.

Delinquency Risk, Loan Size and Percentage Broker Revenues The left figure displays average 12-month delinquency rates as a function of percentage broker revenues. The middle and right figure show, respectively, average percentage revenues and average 12-month delinquency rates for loans in different size bins

The unconditional link between percentage revenues and mortgage credit risk may hold because revenues proxy for other risk characteristics. As shown in the middle panel of Fig. 3, average percentage revenues decline steadily as the loan size increases, from 4.4% for 50-75K loans to 2.2% for 300-500K loans. At the same time, the right panel of the figure shows that small loans are generally also the riskier ones. The average 12-month delinquency rate is highest for 50-75K loans at almost 19%, and then decreases as loan size increases to a low of 11.4% for 200-300K loans and 11.8% for 300-500K loans.

Small loan size—and hence high percentage revenues—serve as strong unconditional indicators of high delinquency risk. In our data, smaller loans are often taken out by lower-income, lower-FICO-score borrowers who tend to purchase or refinance homes in neighborhoods with a higher percentage of minorities and a lower percentage of college graduates.

In the next section, we show that higher broker revenues are associated with higher delinquency risk even when conditioning on the information observed by the lender.

Empirical Results

In this section, we present empirical evidence in support of the hypotheses developed in “Hypothesis Development”. We take the lender’s information set \(\mathcal I\) to be comprised of the variables listed in Table 1. They include loan, property, borrower and broker characteristics, neighborhood and regulation variables, and market conditions, as observed at the time of origination. We refer to these variables as ”observable.” Observable data include mortgage rates but exclude information available only to the borrower and the broker.

A loan transitions from survival to non-survival when it becomes 60 days delinquent or worse for the first time (Demyanyk and Van Hemert 2011). Since mortgage payments are due on a monthly basis, credit events occur only at discrete points in time. To establish a link between conditional broker revenues and delinquency risk we estimate a proportional odds duration model, the discrete-time analogue to the Cox proportional hazard model. For a loan with a given set X of observable characteristics, the probability that the loan transitions to the non-survival state after m months, conditional on not having been delinquent before, is defined as

where TD denotes the time of the credit event.

We assume that the log proportional odds of first-time delinquency at time m are affine in X:

where am captures age effects and bcomp and bcond are row vectors of coefficients. The vector X consists of broker compensation variables, Xcomp, and the observable conditioning variables listed in Table 1, Xcond.Footnote 19 The model is estimated via maximum likelihood techniques under the non-informative censoring assumption.

The estimation results are summarized in Table 6. The first two columns show the parameter estimates when bcomp is set to zero. Our results are consistent with the findings in Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) and Jiang et al. (2014). All else the same, hybrid, balloon and interest-only loans tend to have higher delinquency rates than fixed-rate loans. Piggyback loans, high-LTV loans, limited or stated documentation loans, and loans with prepayment penalties are more likely to become delinquent. Refinance loans, and especially refinance cash-out loans, are less likely to become delinquent. Borrowers with higher credit scores and lower debt-to-income ratios default less frequently on their obligations. Loans originated in neighborhoods with a higher fraction of white population or with higher educational attainment exhibit marginally lower delinquency rates. The unreported age effects are consisted with the findings in Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) in that the odds of first-time delinquency peak around the mortgage age of 8 to 14 months. Conditional delinquency rates increase throughout much of our sample period and peak in 2006.

The vector Xcond includes state-by-state regulation variables. The Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA) of 1994 sets a baseline for federal regulation of the mortgage market. We follow the approach taken by Ho and Pennington-Cross (2006) and construct a “Regulation (coverage)” index that assigns higher positive values if anti-predatory lending laws for a given state cover more types of mortgages relative to HOEPA. In addition, we use the state occupational licensing laws and registration policies for mortgage brokers reported by Pahl (2007) to construct a “Regulation (brokers, Pahl)” index that has higher values for states with stricter requirements.

We find only slightly lower marginal delinquency rates for loans originated in states where a wider range of mortgages is covered under anti-predatory lending laws, but significantly lower rates in states with a higher Pahl index of broker regulation. Stricter broker licensing laws predict lower mortgage credit risk, even when conditioning on other observable risk characteristics.

The third and fourth columns of Table 6 show the estimation results when the restriction on bcomp is lifted and Xcomp measures percentage broker revenues. The results offer strong support in favor of Hypothesis 1—there is a positive association between broker charges and delinquency risk that is statistically significant and economically meaningful even when conditioning on the risk characteristics observed by the lender. A marginal increase in broker revenues by 1% of the loan amount is associated with a 0.062 higher log odds ratio of first-time delinquency, or a \(\exp (0.062)\)-1 = 6.4% higher odds ratio. A one standard deviation increase in percentage revenues is associated with a 0.091 increase in the log odds ratio, or a 9.5% higher odds ratio.

A marginal increase in revenues may stem from a marginal increase in direct fees or a marginal increase in YSP. We replace Xcompb comp′ by bF%Fees + bY%YSP, where %Fees and %YSP denote percentage fees and percentage YSP. The results are reported in columns five and six of Table 6. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, the coefficient estimate \(\widehat b_{F}\) for percentage fees is positive and statistically significant. A marginal increase in fees by 1% of the loan amount is associated with a 0.073 higher log odds ratio, or 7.6% higher odds of delinquency. A one standard deviation increase in percentage fees is associated with a 0.097 increase in the log odds ratio and a 10.2% increase in the odds ratio. The coefficient estimate \(\widehat b_{Y}\) for percentage YSP is not statistically significant. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, YSP provides no additional predictive power for delinquency risk.Footnote 20

Robustness Checks and Extensions

In this section, we perform a number of robustness checks with the goal of lending further support to our finding that high conditional broker fees are associated with high delinquency risk. We then extend our analysis and show that the association between conditional fees and delinquency risk is stronger when there are greater information asymmetries between the borrower and the lender, and when the broker has fewer incentives to transmit precise information to the lender. We conclude by discussing the potential impact of limiting percentage broker revenues on mortgage lending.

Reducing Multicollinearity Concerns

We address the potential issue of collinearity between percentage fees and other predictor variables in Eq. 1 in three ways. First, we re-estimate the model in the last two columns of Table 6 after replacing percentage fees by the residuals obtained from regressing percentage fees on percentage YSP and Xcond. Untabulated results show that the coefficient estimate for residual percentage fees is statistically significant, and that a one standard deviation increase in residual percentage fees is associated with a 8.0% increase in the odds of delinquency.

Second, we form a number of homogeneous loan pools, based on the vintage, size and type of the loan, the borrower’s credit quality and the mortgage rate. For each of the resulting loan pools, Table 7 reports the average 12-month delinquency rates for those loans in the pool with low percentage fees and for those with high percentage fees. For most pools, the delinquency rate is higher for loans with high percentage fees and lower for loans with low percentage fees.

Third, we re-estimate the model in the last two columns of Table 6 for different strata of loans. Strata are formed based on loan type, the borrower’s credit quality, and broker variables.Footnote 21 Results are summarized in Table 8 and confirm the finding that high conditional broker fees predict high mortgage credit risk.

Below we discuss extensions to the model in Eq. 1 that uses Xcompb comp′ = bF%Fees + bY%YSP.

Do High Broker Fees Trigger Mortgage Delinquencies?

Next, we aim to understand whether loans with higher conditional fees turn out to be more risky simply because paying a higher fee at origination leaves borrowers more cash constrained, or whether borrowers who pay higher fees are inherently more risky. If the former were true, the effect of an increase in conditional fees on delinquency risk should be short lived and the impact of conditional fees on the odds of a first-time delinquency in month m should decrease as m increases.

We expand the model in Eq. 1 to include interaction terms between fees and age effects:

The likelihood ratio test of the augmented model (2) against the more restricted model (1) that sets bF,m = 0 for all m has a p-value of 0.472, meaning (1) cannot be rejected. We interpret the lack of evidence that the impact of conditional fees on the odds of delinquency decreases over the lifetime of the mortgage as a strong indication that borrowers who pay higher conditional fees are inherently more risky.

Purchase Versus Refinance Loans

We hypothesize that the link between conditional broker fees and delinquency risk is stronger for purchase loans than for refinance loans. This hypothesis is based on the notion that there tends to be more information available to lenders about borrowers who refinance an existing loan than about borrowers who purchase a home for the first time.Footnote 22 Furthermore, refinance loans tend to have a lower combined loan-to-value ratio than purchase loans.Footnote 23 This implies that borrowers who refinance an existing mortgage tend to have more money invested in the home than borrowers who purchase a home, and thus may be less heterogeneous in their attitude towards delinquency risk and valuation of the put option embedded in non-recourse loans. Consistent with the discussion in “Hypothesis Development”, less information asymmetry between borrowers and lenders or less mispricing of the put option embedded in non-recourse loans may result in a weaker link between broker fees and delinquency risk.

To test the hypothesis that the link between conditional fees and delinquency risk is stronger for purchase loans than for refinance loans, we re-estimate (1) with interaction terms between percentage fees and loan purpose. The results are shown in the top three rows of Table 9, where the interaction terms between percentage fees and loan purpose are further interacted with the documentation level and the borrower’s FICO score, to impose even tighter controls on the level of information asymmetry and potential underpricing for risk. We find that the coefficient estimates for percentage fees are always higher for purchase loans than for refinance loans. We verify that the decrease in the fees coefficient from purchase to refinance loans is statistically significant.

Consistent with the results shown in Tables 9 and 8 reports estimates for the model in Eq. 1 after stratifying the data by documentation level, FICO score and loan purpose. Note that the coefficient estimates for percentage fees are again higher for purchase loans, offering additional support for the hypothesis that a marginal increase in broker fees is associated with an increase in delinquency risk that is larger for purchase loans and smaller for refinance loans.

Broker-Lender Relationship

We refer to brokers who have a close relationship with New Century as “relationship brokers” as opposed to “non-relationship brokers.” Specifically, at any given point in time we label brokers as relationship brokers if they submitted five or more loan applications to New Century in the previous month.Footnote 24 Relationship brokers may value their relationship with the lender more than non-relationship brokers, and hence may be more concerned about the performance of the loans they originate. As a consequence, relationship brokers may transmit more precise information regarding the borrower’s ability to repay the loan to the lender, and may reveal soft information they collect during their negotiations with the borrower. If closer broker-lender relationships result in mortgage rates that are higher for riskier borrowers, then the link between conditional fees and delinquency risk should be weaker for loans originated by relationship brokers.

To test the hypothesis that an increase in broker fees is associated with an increase in delinquency risk that is smaller for loans originated by a relationship broker and larger for loans originated by a non-relationship broker, we re-estimate (1) with interaction terms between fees and a relationship-broker dummy. The results are reported in the bottom three rows of Table 9 and confirm that the coefficient estimates for percentage fees are higher for loans originated by non-relationship brokers than for loans originated by relationship brokers. The decrease in the fees coefficient from loans by non-relationship brokers to loans by relationship brokers is statistically significant, except when interacted with low documentation low-FICO-score loans.

The bottom panel of Table 8 reports estimates for Eq. 1 after stratifying the data by documentation level, FICO score and broker-lender relationship. A one standard deviation increase in percentage fees is associated with an increase in delinquency risk that is smaller for loans originated by a relationship broker and larger for loans originated by a non-relationship broker, offering additional support for our hypothesis that the association between conditional fees and delinquency risk is weaker for relationship brokers.

The Potential Impact of Limiting Percentage Broker Revenues

Our results speak to the potential impact of regulation, such as the Dodd-Frank Act, that limits mortgage broker compensation to a certain fraction of the loan amount. In Appendix C, we show that for a wide range of assumptions underlying the estimation of broker costs, average percentage costs are larger for smaller loans. This is consistent with sizable fixed costs associated with loan origination. At the same time, Fig. 3 highlights that small loans are generally riskier than large loans. Since brokers originate a loan only if revenues are sufficiently high to cover costs, limiting broker revenues to a fixed percentage of the loan amount is likely to constraint the origination of smaller—and unconditionally riskier—loans. Limits on percentage broker revenues are less likely to impose any constraints on larger loans. Moreover, they do not exploit the conditional link between high broker revenues and high mortgage credit risk that we uncover.

Conclusion

Based on a sample of more than 600,000 brokered New Century loans originated between 1997 and 2006, we document that brokers charge higher percentage fees for loans that turn out to be riskier ex post. Conditional on variables observed by the lender, a marginal increase in percentage fees by 1% is associated with 7.6% higher odds of delinquency. While data are available for one lender only, a detailed comparison with other existing descriptive statistics shows that New Century’s loan pool was representative of the broader subprime market. Our main finding that high conditional broker fees predict high mortgage credit risk is supported by several data-focused robustness checks.

We present evidence that borrowers who pay higher conditional fees are inherently more risky, and not simply because paying a higher fee leaves them more cash constrained. We hypothesize that the association between conditional fees and delinquency risk is stronger when there are greater information asymmetries between the borrower and lender, and when the broker has fewer incentives to transmit precise information to the lender. We support our hypothesis by documenting a stronger association between conditional fees and delinquency risk for purchase rather than refinance loans, and for loans originated by brokers who have less frequent interactions with the lender.

The notion that riskier borrowers pay higher broker charges is consistent with the work by Pavlov and Wachter (2009) and Levitin et al. (2020), who show that during the run-up to the subprime crisis that began in 2007, the put option embedded in non-recourse subprime loans was often underpriced. The underpricing of subprime non-recourse loans became more pronounced, and the put option became more valuable, as the borrower’s inherent risk increased. In that sense, riskier borrowers had a greater incentive to pay the broker because it was in their interest to take advantage of loans that were more underpriced for risk.

We decompose broker charges into costs and profits and show that percentage costs tend to be larger for smaller loans. Thus, limiting broker origination charges to a fixed percentage of the loan amount, as was stipulated in the Dodd-Frank Act, is likely to constraint the origination of smaller–and unconditionally riskier—loans. Limiting percentage broker charges is less likely to constrain the origination of larger loans, and it does not exploit the conditional link between high broker charges and high mortgage credit risk that we uncover.

Notes

As of 2005, for example, mortgage brokers originated about 71% of all subprime loans. Detailed information is available at the Mortgage Bankers Association website https://www.mba.org/.

The loan originator compensation rules that went in effect April 1, 2011 as part of the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation Z prohibit mortgage broker compensation to vary based on loan terms, other than principal. As a result, brokers can no longer receive a YSP from the lender for originating a loan at a higher-than-prevailing mortgage rate.

The Dodd-Frank Act, signed into law in 2010 and applicable until modified by the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act of 2018, subjected residential mortgage securitization to credit risk retention requirements. Rule 8 of the Qualified Residential Mortgage restrictions for loans to be exempt from risk retention stipulated that origination charges payable by the borrower in connection with the mortgage transaction, as defined in the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation Z, may not exceed 3% of the loan amount.

Applications of Cox proportional hazard models include (Calhoun and Deng 2002; Pennington-Cross 2003; Deng et al. 2005; Clapp et al. 2006; Pennington-Cross and Chomsisengphet 2007; Bajari et al. 2011) and Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011), among others. Some models allow for flexible baseline functions (Han and Hausman 1990; Sueyoshi 1992; McCall 1996).

For details, see https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/regzcg.htm.

Jiang et al. (2014), among others, document that borrowers who took out low documentation loans during our sample period often falsified information, for example by overstating their income or downplaying their living expenses. Therefore, low documentation loans are also known in the industry as “liar loans.”

This assumption could be relaxed to a situation where the broker gains some negative soft information about the borrower that is not immediately available to the lender.

We abstract from heterogeneity in borrowers’ valuation of their outside option of not receiving the mortgage.

In the notation of Appendix A, a riskier borrower’s subjective discount factor δm is higher than that of a benchmark borrower. As a result, a riskier borrower values hm − pm, and thus ν, more than a benchmark borrower.

Many U.S. residential mortgages are non-recourse loans (Ghent and Kudlyak 2011), that is, they include a put option that limits the borrower’s liability in the event of default to the home used as collateral.

Detailed information is available at the Mortgage Bankers Association website https://www.mba.org/.

About 27% of the YSP entries in our data are left blank. All else the same, loans with lower FICO scores, lower risk grades and less documentation are more likely to have a missing YSP entry. Such loans usually have high base rates, leaving less room for brokers to convince borrowers to pay rates in excess of the base rate. Moreover, while an increase in YSP is usually associated with a decrease in direct broker fees, we find no statistical significance for a missing-YSP dummy when regressing broker fees on YSP and other observable covariates. With this in mind, we interpret missing-YSP entries as zero YSP, which brings the percentage of zero-YSP loans in our data to 30%. Our findings are robust, however, to excluding missing-YSP loans from the sample.

During our sample period, securitization shares of subprime mortgages ranged between 54% and 76% (Inside Mortgage Finance 2007).

The news release does not distinguish between prime and subprime mortgage brokers.

New Century was joined on the OCC’s 2009 list of the biggest subprime lenders in main metro areas by Long Beach Mortgage, Argent Mortgage, WMC Mortgage, Fremont Investment & Loan, Option One Mortgage, First Franklin, Countrywide, Ameriquest Mortgage, ResMae Mortgage, American Home Mortgage, IndyMac Bank, Greenpoint Mortgage Funding, Wells Fargo, Ownit Mortgage Solutions, Aegis Funding, People’s Choice Financial, BNC Mortgage, Fieldstone Mortgage, Decision One Mortgage and Delta Funding.

Whether or not to include mortgage rates in Xcond depends on the objective of the loan performance analysis. Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) argue that subprime loan quality, when adjusted for observable characteristics including mortgage rates, deteriorated prior to the subprime crisis. Jiang et al. (2014) predict first-time delinquency rates for different origination channels and documentation levels. They exclude mortgage rates from the set of predictor variables to avoid endogeneity issues. In our applications, we are interested to understand if broker charges predict delinquency risk when conditioning on all observable characteristics including mortgage rates.

Broker variables include a proxy for broker competition and a measure of how close the broker-lender relationship is. The information content of the latter measure is discussed in detail in “Broker-Lender Relationship”.

Jaffee (2008) reports that the borrower was a first-time homebuyer for one out of five home purchases in the subprime mortgage market between 2000 and 2006. For all but first-time homebuyers, credit reports—which are available to lenders—contain detailed information on borrowers’ payment pattern for previous mortgages.

In our sample, refinance and purchase loans have an average combined loan-to-value ratio of 79% and 94%, respectively.

About one-third of the loans in our sample were originated by relationship brokers. For each broker, New Century also tracked the volume of loan applications submitted in the previous month, and the number and volume of loan applications funded. Our findings are robust to using any of these alternative measures of the broker-lender relationship.

The borrower is matched with the broker either by chance, following a recommendation of a real estate broker or someone else, or as a result of marketing efforts by the broker. We do not model borrower-broker interactions prior to the time that a deal is made.

Our inspection of several lender rate sheets revealed no connection between broker fees and the lender’s base rate. While the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA) of 1994 imposed a number of restrictions on loan features for certain mortgages, including those with very high fees, the ceiling on fees was binding only for a small fraction of loans. HOEPA high-fee loans are defined as loans for which total origination charges exceed the larger of $592 or 8% of the loan amount. The $592 figure is for 2011. The amount is adjusted annually by the Federal Reserve Board, based on changes in the Consumer Price Index. The rules for high-fee loans are listed in Section 32 of the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation Z. “Section 32 mortgages” are banned from balloon payments, negative amortization and most prepayment penalties, among other features.

We only count those brokers whose reservation value for the fees does not exceed the borrower’s benefit from purchasing the house or refinancing the loan.

Woodward and Hall (2012) do not observe broker characteristics and assume that all unobserved heterogeneity in broker costs stems from heterogeneity in costs across brokers. As a result, they cannot identify broker costs in cases where borrowers from only one broker.

Estimates for γ0 and γ are available upon request.

References

Ambrose, B., & Capone, C. (2000). The hazard rates of first and second defaults. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 20, 275–293.

Ambrose, B., & Conklin, J. (2014). Mortgage brokers, origination fees, price transparency and competition. Real Estate Economics, 42, 363–421.

Bajari, P., Chu, S., & Park, M. (2011). An empirical model of subprime mortgage default from 2000 to 2007, Working Paper, University of Minnesota.

Calhoun, C., & Deng, Y. (2002). A dynamic analysis of fixed- and adjustable-rate mortgage terminations. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 24, 9–33.

Chernozhukov, V. (2000). Conditional extremes and near-extremes. Ph.D, Dissertation. Stanford University.

Clapp, J., Deng, Y., & An, X. (2006). Unobserved heterogeneity in models of competing mortgage termination risks. Real Estate Economics, 34, 243–273.

Courchane, M., Surette, B., & Zorn, P. (2004). Subprime borrowers: M,ortgage transitions and outcomes. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 29, 365–392.

Danis, M., & Pennington-Cross, A. (2005). A dynamic look at subprime loan performance. The Journal of Fixed Income, 15, 28–39.

Dawson, C., & Henley, A. (2012). Something will turn up? Financial over-optimism and mortgage arrears. Economics Letters, 117, 49–52.

Demyanyk, Y., & Van Hemert, O. (2011). Understanding the subprime mortgage crisis. The Review of Financial Studies, 24, 1848–1880.

Deng, Y. (1997). Mortgage termination: An empirical hazard model with stochastic term structure. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 14, 309–331.

Deng, Y., Pavlov, A., & Yang, L. (2005). Spatial heterogeneity in mortgage terminations by refinance. Real Estate Economics, 33, 739–764.

Deng, Y., & Quigley, J.M. (2000). Robert Van Order, Mortgage terminations, heterogeneity and the exercise of mortgage options. Econometrica, 68, 275–307.

Dickinson, A., & Heuson, A. (1994). Mortgage prepayments: P,ast and present. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 2, 11–34.

Federal Reserve Board (2008). Design and testing of effective truth in lending disclosures: Findings from experimental study, Report submitted by Macro International Inc.

Garmaise, M. (2009). After the honeymoon: Relationship dynamics between morgage brokers and banks. Working paper, University of California Los Angeles.

Gerardi, K., Goette, L., & Meier, S. (2010). Financial literacy and subprime mortgage delinquency: Evidence from a survey matched administrative data. Working paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Ghent, A., & Kudlyak, M. (2011). Recourse and residential mortgage default: E,vidence from U.S. states. The Review of Financial Studies, 24, 3139–3186.

Gorton, G. (2010). Slapped by the Invisible Hand: The Panic of 2007. New York: NY).

Han, A., & Hausman, J. (1990). Flexible parametric estimation of duration and competing risk models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 5, 1–28.

Heuson, A., Passmore, W., & Sparks, R. (2001). Credit scoring and mortgage securitization: I,mplications for mortgage rates and credit availability. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 23, 337–363.

Ho, G., & Pennington-Cross, A. (2006). The impact of local predatory lending laws on the flow of subprime credit. Journal of Urban Economics, 60, 210–228.

Hong, P., & Reza, M. (2005). Hidden costs to homeowners: T,he prevalent non-disclosure of yield spread premiums in mortgage loan transactions. Loyola Consumer Law Review, 18, 131–150.

Inside Mortgage Finance (2007). Mortgage market statistical annual, Report by Inside Mortgage Finance Publications, Inc.

Jackson, H., & Burlingame, L. (2007). Kickbacks or compensation: The case of yield spread premiums. Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance, 12, 289–361.

Jaffee, D. (2008). The U.S. subprime mortgage crisis: Issues raised and lessons learned. Berkeley: Working Paper, University of California.

Jiang, W., Nelson, A., & Vytlacil, E. (2014). Liar loans? Effects of loan origination and loan sale on delinquency. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96, 1–18.

Kau, J., & Keenan, D. (1995). An overview of the option-theoretic pricing of mortgages. Journal of Housing Research, 6, 217–244.

Kau, J., Keenan, D., & Kim, T. (1993). Transaction costs, suboptimal termination and default probabilities. Journal of Housing Research, 21, 247–263.

Kau, J., Keenan, D., Muller, W., & Epperson, J. (1992). A generalized valuation model for fixed-rate residential mortgages. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 24, 279–299.

Lacko, J., & Pappalardo, J. (2007). Improving consumer mortgage disclosures: An empirical assessment of current and prototype disclosure forms, Federal Trade Commission Staff Report.

LaCour-Little, M. (2009). The pricing of mortgages by brokers: An agency problem?. Journal of Real Estate Research, 31, 235–263.

Landier, A., Sraer, D., & Thesmar, D. (2015). The risk-shifting hypothesis: Evidence from subprime originations. Working paper, HEC Paris.

Levitin, A., Lin, D., & Wachter, S. (2020). Mortgage risk premiums during the housing bubble. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 60, 421–468.

McCall, B. (1996). Unemployment insurance rules, joblessness, and part-time work. Econometrica, 64, 647–682.

McCoy, P. (2017). Has the mortgage pendulum swung too far: Reviving access to mortgage credit has the mortgage pendulum swung too far: R,eviving access to mortgage credit. Boston College Journal of Law and Social Justice, 37, 213–234.

Moody’s (2005). Spotlight on New Century Financial Corporation, Moody’s Special Report.

Pahl, C. (2007). A compilation of state mortgage broker laws and regulations 1996-2006, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Affairs Report.

Pavlov, A., & Wachter, S. (2009). Mortgage put options and real estate markets. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 38, 89–103.

Pennington-Cross, A. (2003). Credit history and the performance of prime and nonprime mortgages. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 27, 279–301.

Pennington-Cross, A., & Chomsisengphet, S. (2007). Subprime refinancing: Equity extraction and mortgage termination. Real Estate Economics, 35, 233–263.

Reuters (2011). Can brokers still earn the same commission? 360 mortgage group provides insights on broker compensation after the Federal Reserve Board rule. Marketwire report June 10.

Stiglitz, J., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. American Economic Review, 71, 393–410.

Sueyoshi, G. (1992). Semiparametric proportional hazards estimation of competing risks models with time-varying covariates. Journal of Econometrics, 51, 25–58.

Titman, S., & Torous, W. (1989). Valuing commercial mortgages: A,n empirical investigation of the contingent-claims approach to pricing risky debt. The Journal of Finance, 44, 345–373.

Woodward, S. (2003). Consumer confusion in the mortgage market. Working Paper, Sand Hill Econometrics.

Woodward, S., & Hall, R. (2012). Diagnosing consumer confusion and sub-optimal shopping effort: T,heory and mortgage-market evidence. American Economic Review, 102, 3249–3276.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Glascock (editor) and two anonymous referees for their insightful comments. We are grateful for financial support from the Darden School Foundation, the McIntire Center for Financial Innovation, and SIFR. We are indebted to Vijay Bhasin, Bo Becker, Sonny Bringol, Dwight Jaffee, Gyongyi Loranth, Atif Mian, Amit Seru, Amir Sufi, Alexei Tchistyi and Nancy Wallace for helpful feedback and discussions, and to Michael Gage of IPRecovery, Inc. for technical support. We thank seminar participants at numerous universities, institutions and conferences for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: A Simplified Model of the Mortgage Origination Process

We develop a simple model of the mortgage origination process to understand how broker origination charges are determined and what they may reveal about mortgage credit risk. We focus on loans originated in the wholesale market, where independent mortgage brokers act as financial intermediaries matching borrowers with lenders. Brokers assist borrowers in the selection of the loan and in completing the loan application, and provide services to wholesale lenders by generating business and helping them complete the paperwork.

Consider a borrower who arrives at a broker requesting a mortgage.Footnote 25 The broker evaluates the borrower’s and the property’s characteristics, and based on that information provides the borrower with one or more financing options. A financing option consists of a specification of the loan terms such as the loan amount, type of loan and level of income documentation, and of the associated mortgage rate. It also outlines the fees the broker will charge the borrower.

To compile the list of financing options, the broker reviews wholesale rate sheets distributed by potential lenders. These rate sheets state the minimum rate at which a given lender is willing to finance a loan, as a function of loan, borrower and property characteristics. We refer to this rate as the lender’s base rate. Rate sheets also inform the broker about the YSP, if any, that the lender pays to the broker for originating the loan at a rate higher than the base rate. The borrower and the broker bargain over the terms of the loan, the rate and the fees. Once they reach an agreement, the broker submits a funding request to one or more lenders. The lender reviews the application material and responds with a decision to fund the loan or not. If the loan is funded, the broker receives the fees and YSP at the loan closing.

Suppose that a lender will fund the loan as long as the broker collects and transfers the requested application materials and secures a rate at or above the lender’s base rate. Since the broker is paid only if the loan is made, they will only offer fundable proposals to the borrower and will ensure that the application materials are presented to the lender in a timely fashion. Let L denote the vector summarizing the terms of the loan including the loan type, the loan amount, the loan maturity, the documentation level, and any prepayment penalties. The initial mortgage rate r has to be at or above the base rate of the lender to whom the loan application is submitted. We use f to denote the fee that the broker charges the borrower for originating the loan. Each vector (L,r,f) represents a financing option, and the borrower and broker have to agree on L, r and f.

The borrower’s net benefit from the loan is \(\overline f-f\), where \(\overline f\) denotes the borrower’s reservation value for the fees and is given by \(\overline f = \nu -o\). Here, ν measures the dollar value of the benefits the borrower expects to draw from owning the home in excess of the expected present value of the mortgage payments for the loan (L,r). We use o to denote the dollar value of the borrower’s outside options as perceived by the borrower at the time the deal is made. The entire benefit that the borrower perceives to gain from purchasing the house or refinancing the loan is ν − o(no mortgage), where o(no mortgage) is the value of not receiving the mortgage. We refer to ν − o(no mortgage) as the borrower’s valuation for the loan.

Let y denote the YSP paid by the lender and c denote the broker’s cost of originating the loan. Broker costs are the costs the broker expects to incur between the time they strike a deal with the borrower and the time the loan is funded. They include the broker’s time costs of dealing with the borrower as well as any administrative costs paid by the broker for intermediating the mortgage. The broker’s reservation value for the fees, \(\underline f\), is equal to

and the broker’s net benefit from originating the loan is \(f-\underline f\).

The borrower’s and broker’s joint surplus is the sum of their respective benefits,

We consider a simple model of bargaining between the borrower and broker where the broker learns the borrower’s reservation value \(\overline f\) and has all the bargaining power. The broker maximizes their net benefit f + y − c by choosing the lender and (L,r,f), subject to the borrower’s participation constraint, f ≤ ν − o, and to the broker’s participation constraint, f ≥ c − y.

We assume that fees f can be set without a feedback effect on other terms of the loan.Footnote 26 Under this assumption, the broker sets the fee equal to the borrower’s reservation value,

From Eqs. 3 and 5 the broker’s net benefit is ν − o + y − c, meaning the broker captures all the joint gains from trade in Eq. 4. The terms of the loan and the mortgage rate are set so as to maximize those gains from trade, provided that the broker’s revenues cover the costs, f + y ≥ c.

The broker’s total revenues are \(f+y = c + \left (\nu -o+y-c \right )\). The revenues are equal to the cost of intermediating the loan plus the surplus that the broker is able to capture. We refer to the surplus ν − o + y − c captured by the broker as broker profit. Note that these profits are inclusive of the costs of identifying and attracting prospective borrowers.

The borrower’s shopping behavior determines the value of their outside options, o, and therefore the broker fees. Let K denote the number of brokers the borrower shops from. If K = 1, the borrower shops from only one broker and the outside option is no mortgage. The broker can extract the entire benefit that the borrower perceives to gain from purchasing the house or refinancing the loan, and fees are equal to the borrower’s valuation for the loan, ν − o(no mortgage).

If K ≥ 2, the borrower shops from multiple brokers.Footnote 27 Similar to Woodward and Hall (2012), we assume a second-price auction process where the borrower seeks initial quotes from K brokers and uses these quotes to extract better proposals until the process ends with one quote that no other broker is willing to beat. The observed revenue is the cost of the second-lowest-cost broker. The originating broker extracts all of the surplus in the bargain with the borrower, whose outside option is to accept the runner-up bid. In summary, the originating broker’s revenue is equal to

Equation 6 states that brokers extract high conditional fees from borrowers who shop from few brokers, including borrowers with a high conditional valuation for the loan that shop from only one broker, and from borrowers who shop from multiple brokers but for whom brokers perceive conditional costs to be high.

Equation 6 suggests that heterogeneity in broker revenues may be due to heterogeneity in the borrowers’ valuation for their loan, ν − o(no mortgage). Assuming that the borrower is risk-neutral, ν is given as

where T denotes the maturity of the loan, TP is the time at which the borrower prepays the loan in full, TD is the time of mortgage default, δm is the borrower-specific discount factor for spending or receiving one dollar m months from now and 1{⋅} denotes the indicator function.

We use hm to denote the value the borrower receives from occupying in the house in month m, and Hm to denote the time-m value that the borrower receives from the home from month m on. The mortgage is terminated early if either prepayment or default occurs prior to the original maturity date. The payments made in month m are denoted by pm. They include the principal and interest payments due after m months, and may also include any additional downpayments on principal that the borrower plans to make. The term p0 captures net payments due at closing, in addition to the fees charged by the broker. They include the downpayment for the loan and lender discount points. For a refinance loan, the amount of cash taken out, if any, would be subtracted.

If the loan is paid off early after m months, Bm denotes the outstanding balance on the mortgage at that time. If the current loan is refinanced after m months, then Bm measures the time-m value of the payments associated with the new mortgage, including any fees to obtain the refinance mortgage, minus the cash taken out. If the house is sold after m months, Hm = hm and Bm denotes the outstanding balance on the mortgage minus the sales price. Fm are the costs the borrower incurs from mortgage default at the end of month m, other than having to give up the house. Expectations are taken with regard to the joint probability distribution of

Appendix B: Sample Construction and Variable Definition

The raw New Century dataset contains 3.2 million loans. We keep all wholesale loan applications between 1997 and 2006 that were either funded, declined or withdrawn. We require records to contain the broker id, the property zip code, a loan amount between 10K and 1,000K, a combined loan-to-value ratio between 0 and 150, a FICO score between 300 and 850, a debt-to-income ratio between 0 and 100, and a mortgage rate between 0 and 25%. This leaves us with roughly 1.5 million broker loans which we use to compute broker variables. We then restrict the sample to include only funded loans, which yields roughly 768,000 observations.