Abstract

The present study aimed to examine the contributions of two separate Pinyin skills and oral vocabulary to Chinese word reading of 70 third graders in a U.S. Mandarin Immersion program where Pinyin was introduced at Grade 3. Hierarchical regression analyses showed that Pinyin initial-final spelling—the skill to spell Chinese syllables using Pinyin letters—and oral vocabulary were uniquely associated with Chinese word reading, after accounting for the effects of phonological awareness and the other Pinyin skill of tone identification. The variance in Chinese word reading explained by tone identification was fully accounted for by oral vocabulary, Pinyin initial–final spelling, and phonological awareness, suggesting that tone identification might involve both phonology- and meaning-related processes. Oral vocabulary and tone identification explained more shared variance in Chinese word reading than the two code-related skills of phonological awareness and Pinyin initial-final spelling. The importance of meaning-related skills in learning the deep orthography of Chinese characters for Chinese L2 young learners is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Language immersion, an alternative educational program to the public education system in the U.S., has been the most successful school-based foreign language program model for young learners to achieve a high level of second language (L2) proficiency at no cost to their first language (L1; e.g., Genesee, 2004; Hamayan et al., 2013; Lindholm-Leary, 2001). Different from traditional foreign language education, immersion students spend 50% or more of their instructional time and learn school subject matter in a foreign language throughout the entire elementary grades (Fortune & Tedick, 2003). Mandarin immersion (MI) is a newcomer to immersion education, but it has become a popular program model in the U.S. To date, thousands of English-speaking children learn Chinese as a foreign language in more than 300 MI programs (Mandarin Immersion Parents Council, 2020). Not surprisingly, these young Chinese L2 learners have experienced challenges in learning to read the nonalphabetic character writing system (Burkhauser et al., 2016; Fortune & Song, 2016; Watzinger-Tharp et al., 2018). Better understanding of the processes that contribute to Chinese character learning is of theoretical and practical importance for MI learners and L2 learners of Chinese in general.

Several decades of research has focused on the roles of cognitive, metalinguistic, and linguistic skills on early literacy development across cultures (August & Shanahan, 2006; Koda & Zehler, 2008; McBride, 2016). The most well-documented code-related skill in alphabetic literacy research is phonological awareness (e.g., Ehri et al., 2001; Rayner et al., 2001; Ziegler & Goswami, 2006). In contrast, substantial studies suggest that the role of the broadly defined meaning-related skills (e.g., morphological awareness, oral vocabulary) may be more important than phonological awareness in Chinese reading (e.g., Hulme et al., 2019; Shu et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2009). It is unclear if the meaning-related skills are more important than code-related skills in English-speaking children who learn Chinese as a L2. The present study aimed to address this research question by focusing on Pinyin spelling skills and oral vocabulary in MI learners. This is because Pinyin spelling is recently considered a more optimal tool than conventional phonological measures (Ding et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2010; Zhang & Roberts, 2020). Also, the research to investigate the effect of oral vocabulary, relative to morphological awareness, on Chinese word reading is scarce but important because of the compounding structure of Chinese words, language exposure and instructional constraints on Chinese L2 learners (Kuo & Anderson, 2006; Tong et al., 2017; Zhang & Koda, 2018; Zhou, 2012).

The deep orthography of Chinese characters

The concept of orthographic depth describes the transparency of alphabetic orthographies based on how reliable a grapheme corresponds to a phoneme (Frost et al., 1987; Katz & Frost, 1992). English is one of the most unreliable alphabetic orthographies with many grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence exceptions (Seymour et al., 2003; Ziegler et al., 2010). Chinese characters can be considered a deeper orthography than English because each Chinese character correspond to one syllable without phoneme level or tone representations in the orthography (Lin, 2007; Perfetti, 2003). Although the majority of characters contain phonetic components, only 23% of the characters have phonetic components that provide reliable onset, rime, and tone (Shu et al., 2003). Because the mapping between sound and print in Chinese only takes place at the level of the syllable, the number of orthography-to-phonology mappings is enormous: children need to learn the 3,500 commonly used Chinese characters that correspond to approximately 1,200 tonal syllables (Anderson & Li, 2006; Anderson et al., 2013).

Pinyin spelling in Chinese word reading

As a sound transcription system for Chinese characters, the Pinyin system uses 26 letters and four diacritics to represent syllables at the phoneme level and tones of spoken Chinese. According to the Scheme of the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet (Committee of Chinese Writing System Reform, 1958), Pinyin has 21 initials (i.e., syllable-initial consonants), 35 finals (i.e., vowels which may be preceded by a glide and/or followed by a consonant) and 4 tones. Compared to the English orthography, Pinyin is fairly transparent. The majority of Pinyin initials and finals have a one-to-one correspondence. However, the vowels in Pinyin finals have one-to-many or many-to-one sound to symbol mapping relationships (Li & Thompson, 1981).

A recent argument was that children’s self-directed attempts to represent Chinese sounds using Pinyin letter knowledge and tone marks, defined as Pinyin invented spelling, could be an optimal measure of Chinese phonological awareness (Ding et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2010; Zhang & Roberts, 2020). Phonological awareness, the ability to identify and manipulate sounds, has been well studied in alphabetic language literacy development (see the detailed review in Rayner et al., 2001). Syllable, onset-rime, and tone levels of phonological awareness were also found to be significantly associated with Chinese word reading for Chinese L1 children at the early stages of reading development (e.g., Ho & Bryant, 1997; Shu et al., 2008). Different from the traditional measures to gauge phonological awareness, Pinyin invented spelling is typically assessed by audially presenting a set of Chinese syllables to the spellers and asking them to spell the sounds using Pinyin initials, finals, and tones. In studies on Chinese L1 learners, Lin et al. (2010) found that syllable awareness and Pinyin invented spelling were significantly correlated with each other and with Chinese character reading in Chinese kindergarteners, but Pinyin invented spelling was a stronger predictor than syllable awareness for Chinese word reading. Similarly, Ding et al. (2015) showed that Pinyin invented spelling was more sensitive than a traditional measure used to examine differences in phonological awareness for older Chinese children at fourth grade. Studies on Chinese L2 learners demonstrated similar results. Lü (2017) reported that Pinyin invented spelling was a statistically significant predictor above and beyond traditional phonological awareness in second graders within a MI program. Additionally, Zhang and Roberts (2020) revealed that Pinyin invented spelling was a more sensitive test than an oddity test used to measure Chinese phonological awareness between English and Arabic Chinese L2 adult learners.

There are at least two gaps in the literature regarding Pinyin invented spelling. The first gap is that in most studies Pinyin invented spelling was assessed and quantified as a holistic score that combines the score of Pinyin initial and final spelling (henceforth Pinyin initial-final spelling) and the score of tone identification when entered as an explanatory variable to predict Chinese word reading (Lin et al., 2010; Lü, 2017; Zhang & Roberts, 2020). In fact, Pinyin invented spelling may contain two related but different skills. One skill is Pinyin initial-final spelling, which is a code-related skill that requires the spellers to identify phonological elements in a Chinese syllable at the segmental level and apply Pinyin letter knowledge. The other skill is tone identification, which necessitates the ability to identify tone values—a phonological skill at the supersegmental level—and tone mark knowledge. The ability to identify tones was also found to be a unique predictor of oral vocabulary and Chinese word reading in Chinese L1 children with and without dyslexia (Li & Ho, 2011; McBride-Chang et al., 2008; Tong et al., 2015). Additionally, lexical tone influences the processing of a character’s meaning: tone change of a syllable can alter the meaning of the syllable. Therefore, it is hypothesized that tone identification might involve both phonology- and meaning-related skills. Combining the two distinct skills into one could confound the relationship of each skill with Chinese word reading and with other character literacy related skills. One goal of the present study was to investigate the extent to which the two separate Pinyin skills (i.e., Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification) are different from each other and the construct of phonological awareness in contributing to Chinese word reading.

The second gap in the current literature is the extent to which the two separate Pinyin skills make unique contributions to Chinese word reading above and beyond other literacy-related subset skills. This is due to the fact that the interrelations of phonological, orthographic, and semantic knowledge could contribute to Chinese word reading at different developmental stages of reading. However, studies on Pinyin invented spelling have focused mostly on one dimension of the metalinguistic skills, that is, phonological processing skills. For example, Lin et al. (2010) measured Pinyin letter-name knowledge, Pinyin invented spelling, syllable deletion, phoneme deletion, and earlier word reading. Similarly, Lü (2017) also used Chinese phonological awareness and earlier word reading as predictor variables. Although Pinyin invented spelling was significantly correlated with Chinese word reading and made a significantly unique contribution to Chinese word reading, above and beyond phonological awareness and earlier Chinese word reading, it is unclear if the unique variance explained by Pinyin invented spelling can be accounted for by other reading related skills. The less specified models in the above-mentioned studies could bias the estimates and influence our inferences.

Only one study, Zhou and McBride (2015), assessed phonological awareness with the parsed Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification. It was found that the difference in Chinese word reading may only be explained by tone awareness in Chinese L1 and L2 third and fourth graders, but not by Pinyin initial-final spelling, after controlling for age, nonverbal intelligence, oral vocabulary, and Chinese backward digit recall. More studies are warranted to examine the two separate Pinyin skills and other literacy-related skills and explore their interrelations with Chinese word reading in L2 learners of Chinese.

Oral vocabulary in learning to read Chinese

Although phonological processing skills are essential for alphabetic language reading, meaning-related skills may be more important for Chinese word reading (McBride-Chang et al., 2005; Shu et al., 2006; Wang & McBride, 2016). For example, a cross-language comparison study explored the contributions of phonological awareness and morphological awareness to reading across scripts in second graders from Chinese-speaking and English-speaking societies (McBride-Chang et al., 2005). The study found that phonological awareness significantly explained unique variance in English word reading but morphological awareness did not. In contrast, morphological awareness was a statistically significant predictor above and beyond phonological awareness and oral vocabulary in Chinese word reading, but phonological awareness was not.

Although previous research has focused on the comparison of the effects between morphological and phonological awareness on Chinese word reading, the relative importance of another meaning-related skill of oral vocabulary, in comparison to phonological processing skills, in the developmental models of reading is less clear. Oral vocabulary has often been treated as a control variable (Tong et al., 2017). This research topic on oral vocabulary is theoretically important for at least two reasons. First, the influence of morphological awareness at sublexical and lexical levels to Chinese word reading may be partially or fully mediated by oral vocabulary (Tong et al., 2017). Second, the development of morphological awareness may depend on language input and instruction. Chinese L2 children may process and store lexicons in a different way than Chinese L1 children and their morphological awareness development may be constrained by their Chinese language exposure or instruction on the morphemes in characters and words (Zhang & Koda, 2018; Zhou, 2012).

In general, oral vocabulary has been considered an important factor of Chinese word reading in Chinese L1 children (McBride, 2016). The predictive effect of oral vocabulary on character literacy may be affected by the measures used in different studies. For example, the nonsignificant correlation between oral vocabulary and Chinese word reading in Yeung et al. (2013) may be attributable to the method of assessing oral vocabulary by counting word tokens that children used to describe the pictures. Studies that measured oral vocabulary using receptive, expressive, and/or definitional vocabulary tests showed that oral vocabulary has similar predictive value as phonological processing skills on early literacy development for Chinese L1 children (Hulme et al., 2019; McBride-Chang & Ho, 2005; Zhang et al., 2013). In some cases, phonological processing skills may even be stronger in younger children. Wang and McBride (2016) reported that oral vocabulary was only slightly associated with Chinese word reading (r = 0.19, p < 0.05), but not with character reading in Chinese L1 kindergarteners. In contrast, phonological awareness and holistic Pinyin invented spelling had moderate correlations with both Chinese character and word reading (r = 0.24, p < 0.01). Additionally, a five-year longitudinal study revealed that phonological sensitivity measures (both syllable awareness and Pinyin spelling) and oral vocabulary assessed at age 5 could predict Chinese character recognition at age 8 years, 9 years, and 10 years, but phonological sensitivity measures could also predict Chinese character recognition at age 7 years (Pan et al., 2011).

The higher predictive value of oral vocabulary than phonological awareness in predicting Chinese word reading in older children is consistent across studies, indicating that a broader vocabulary knowledge may facilitate the process of connecting the sound and shape of characters, whereas phonological advantage may not. For example, in a study by Huang and Hanley (1995) that recruited Chinese L1 third graders, the unique variance in Chinese word reading explained by phonological awareness was accounted for by oral vocabulary, and superior phonological awareness was not associated with higher Chinese word reading, after accounting for oral vocabulary. Additionally, Shu et al. (2006) reported that oral vocabulary was a significant predictor that distinguished dyslexic children from children without reading difficulties in grades 5 and 6, but phonological awareness did not.

The prior research on Chinese L2 learners showed that L2 learners of Chinese typically develop their oral language and literacy skills hand in hand in classrooms, so their oral vocabulary could be strongly associated with their reading skills in Chinese. For example, knowing the pronunciation and being able to explain the meaning of the Chinese words are strongly correlated in adult L2 learners of Chinese (r = 0.96, p < 0.0001; Everson, 1998). Additionally, Zhou and McBride (2015) found that oral vocabulary was a unique and the strongest predictor of Chinese word reading for both Chinese L1 and L2 third and fourth graders after controlling for other cognitive, phonology- and orthography-related skills. More studies are needed to examine the relative importance of oral vocabulary and phonological processing skills in reading acquisition for alphabetically minded L2 learners of Chinese in a variety of bilingual and Chinese as a foreign language programs.

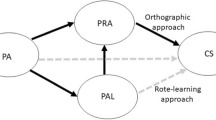

Together, the aforementioned studies suggest that oral vocabulary may be an important predictor of Chinese word reading, especially for Chinese L2 learners. In spite of the fact that previous studies were mostly interested in whether or not the predictive effect of holistic Pinyin invented spelling exerts influence over phonological awareness, the literature reviewed to this point suggests that there is a need to consider the interrelations between oral vocabulary, the two separate Pinyin skills, and Chinese word reading in Chinese L2 children. Additionally, it is theoretically important to understand the relative importance of code-related skills (Pinyin initial-final spelling, phonological awareness) and skills that may involve meaning (tone identification, oral vocabulary) in learning to read the deep orthography of Chinese.

The overall goal of the present study was to examine the contributions of the two separate Pinyin skills and oral vocabulary to Chinese word reading in MI third graders. The specific research questions are summarized as follows:

RQ1 To what extent do the two separate Pinyin skills (i.e., Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification) and oral vocabulary uniquely predict Chinese word reading? Do the two separate Pinyin skills each tap into the same construct of phonological awareness in Chinese word reading?

RQ2 What is the relative importance of code- and meaning-related skills (i.e., Pinyin initial-final spelling, phonological awareness vs. tone awareness, oral vocabulary) in Chinese word reading?

Method

School setting and participants

Located in a Midwest state of the U.S., the school is an early total MI program implementing the intensive program model with approximately 90% of instructional time in Mandarin from kindergarten for all core content subjects. According to the self-report of the academic director, by Grade 5, students are expected to recognize about 2000 Chinese characters and produce 1500 characters. Students began character reading and writing in kindergarten. From the beginning of Grade 2, students were introduced to English literacy with seven English language arts class periods per week. The teachers engaged students in a variety of character literacy activities to connect meaning, sound, and shape of characters, including explaining the meaning of a character/word, choral reading, sub-character analysis, handwriting, etc. At Grade 3, Pinyin initials and finals were taught in eight weeks, three or four symbols in each class period. Pinyin introduction relied on phonics training to associate Pinyin graphemes and Chinese sounds in meaningful contexts, such as connecting a Pinyin initial or final with a familiar word that contains the sound, reading aloud Pinyin initials and finals, spelling and providing corrective feedback. As students became familiar with Pinyin knowledge at the end of Grade 3, teachers captioned unfamiliar characters with Pinyin in reading materials.

As part of a larger research project that examined Pinyin spelling and the use of Pinyin to learn Chinese in MI students, the present study recruited a total of 76 third graders from this MI program. Seventy students (35 girls and 35 boys) completed all tasks in the study. Based on the results reported in an earlier study (Fortune & Song, 2016) that assessed MI students’ oral proficiency in the same state as the present study, most students at Grade 2 were expected to range in Intermediate levels of Chinese oral language proficiency using rating scales that were adapted for young learners and aligned with the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Proficiency Guidelines (Swender et al., 2012). The school has excellent academic performance; the majority of the third graders could meet and exceed academic standards in reading and math in the state standardized assessments in English. The racial composition of the school is mainly White and Asian. Although a noticeable proportion of students have Asian ethnic backgrounds, the majority of students speak English as their first or dominant language. Only a small percentage of students receive free or reduced-price lunch or special education services.

Measures and instruments

Chinese word reading

The response variable reflected students’ character literacy outcomes captured through Chinese word reading. The Chinese word reading task adapted the tasks in Zhou and McBride (2015) with single-character (20 items) and two-character (60 items) words. These words were chosen from participating students’ Chinese textbooks and storybooks in consultation with classroom teachers. The words were selected based on the specificity and abstraction of word meaning, part of speech, and orthographic complexity. The students were asked to name each word presented on an easel display stand. Scores were based on the number of words they named correctly. The total score for this task was 80. If a child failed to recognize 10 item words consecutively, the testing was stopped and the number of correctly named words was recorded as their score. The task was administered individually by trained research assistants.

Oral vocabulary

The Chinese oral vocabulary task used to assess the children’s receptive and expressive vocabulary knowledge in the study was translated and adapted from the English standardized Peabody Pictures Vocabulary Test-4 (Dunn & Dunn, 2007) and the Expressive Vocabulary Test-2 (Williams, 2007). All the selected vocabulary items appeared in students’ previous textbooks or storybooks. In the receptive vocabulary section (45 items), students were asked to listen to a Chinese word orally presented by the examiner and point to one of four pictures to indicate the meaning of the word they heard. In the expressive vocabulary section (15 items), students were asked to name the objects or describe people’s actions or emotions in the picture. The task was administered individually by trained research assistants. Each item was worth 1 point. The total score of the measure was 60.

Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification

To assess students’ Pinyin skills, students were asked to spell Chinese syllables using Pinyin initials and finals and diacritic tone marks. The task expanded the measure used in Zhou and McBride (2015) by including 41 tonal syllables that covered all Pinyin initials and finals. For each syllable, the response was coded separately for onset (1 point), rime (1 point), and tone (1 point). An onset includes the possible syllable-initial consonants and the glide; a rime begins with the vowel and includes, possibly, a syllable-final consonant. This syllable analysis is based on the principle that divides the syllable structure at the most sonorous element (Selkirk, 1982). This coding was more appropriate than the traditional Chinese syllable analysis that assigns the glide in the finals because the number of phonemes and the scores allocated for the onset and rime in a syllable were more equal. For example, in the syllable jiang, the four phonological elements /tɕjɑŋ/ in the syllable can be more evenly parsed and scored between onset /tɕj/ and rime /ɑŋ/. Because the study was interested in exploring the effects of the two separate Pinyin skills, the scores of Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification were calculated separately. The total possible score was 82 for the measure of Pinyin initial-final spelling and 41 for the measure of tone identification. The task was administered in groups of four to six students with paper and pencil.

Chinese phonological awareness

Adapted from the measure used in Zhou and McBride (2015), the task in the present study included 5 items of syllable deletion and 15 items of syllable-initial phoneme deletion. The total score of the task was 20. If a child failed to name 10 item words consecutively, the testing was stopped, and a score was assigned based on the number of the items answered correctly. The task was administered individually by trained research assistants.

Control variables

Invented spelling of English nonwords was identified as the first control variable that may confound Pinyin spelling and Chinese word reading. English Invented spelling taps into English-speaking children’s phonological and orthographic processing skills in English (McBride-Chang, 1998). Nonwords were used to rule out the influence of familiar word spelling knowledge. Participants listened to the pronunciation of English nonwords recorded by an adult female native English speaker. This task was adapted from Campbell (1985) and the coding was based on the possible spellings provided in the study. Each nonword has only one syllable. The correct spelling of each onset or rime in the syllable was awarded 1 point so that each nonword was worth 2 points. There were 15 items in the task, and the possible total score was 30. The task was administered in groups of four to six students with paper and pencil.

Another control variable was children’s visual-motor and character orthographic memory assessed by the task of delayed copying (Shu & Anderson, 1997; Zhou, 2012). Participants were asked to view a character for 5 s and then write down the character. Each character could be divided into two components, each worth 1 point, and the correct position of the two components was also awarded 1 point for a possible total score of 3 points for each character. There were 6 characters in the task for a total score of 18. The task was administered in groups of four to six students with paper and pencil.

Lastly, student ages were converted to a numeric value by year.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were first carried out to identify patterns of the variables. Next, hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed to characterize the extent to which the identified variables were associated with Chinese word reading. Eta square estimation (Levine & Hullett, 2002) and dominance analysis (Budescu, 1993) were performed to calculate the unique and average contributions of the identified variables. Model assumptions of normally distributed residuals, homogeneous variances, and low variance inflation were assessed.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency results (Cronbach’s α) of the variables were reported in Table 1. The internal consistency for all the measures was above satisfactory reliability levels (≥ 0.70). The correlation between each pair of variables was reported in Table 2.

Chinese word reading had a statistically significant correlation with the variables that tapped into phonological awareness, oral vocabulary, and the two separate Pinyin skills, but not with the control variables (i.e., English nonword spelling, orthographic skill, or age). The strongest correlations with Chinese word reading were oral vocabulary and tone identification, both of which also had a significant association with each other. The two separate Pinyin skills (i.e., Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification) were significantly correlated with each other and with phonological awareness. Pinyin initial-final spelling was also significantly associated with English nonword spelling, but not with oral vocabulary. On the contrary, tone identification did not have a significant correlation with English nonword spelling.

Hierarchical linear regression analyses

The first research question asked the following: To what extent do the two separate Pinyin skills and oral vocabulary uniquely predict Chinese word reading? Do the two separate Pinyin skills each tap into the same construct of phonological awareness in Chinese word reading? Hierarchical linear regression was used to address this set of questions.

The variables, including the two separate Pinyin skills, oral vocabulary, and phonological awareness were all significantly correlated with Chinese word reading and were selected to form the baseline regression model. To examine the extent to which the code-related (Pinyin initial-final spelling, together with phonological awareness) and the two meaning-related variables (tone identification and oral vocabulary) could predict Chinese word reading, three sets of regression analyses were conducted by entering phonological awareness and Pinyin initial-final spelling in Model 1, adding tone identification in Model 2, and finally adding oral vocabulary in Model 3. The present study introduced tone identification and oral vocabulary in the models after Pinyin initial-final spelling and phonological awareness to examine if the two meaning-related variables could explain more variance above and beyond the code-related skills.

The results from Model 1 indicated that the two code-related variables, Pinyin initial-final spelling and phonological awareness, were both unique predictors of Chinese word reading (see Table 3). Adding tone identification in Model 2 increased the percentage of variance explained in Chinese word reading by eight percentage points. However, the two code-related variables were no longer significant predictors, and only tone identification accounted for a statistically significant amount of variance in Chinese word reading. This indicates that a large portion of the variance in Chinese word reading explained by Pinyin initial–final spelling and phonological awareness was shared in common with tone identification, reducing the unique variance accounted for by the other two explanatory variables to the point that their contributions were no longer statistically significant. Adding the meaning-related variable of oral vocabulary in Model 3 resulted in a large increase of 16 percentage points in the percentage of variance explained in Chinese word reading. However, only oral vocabulary and Pinyin initial-final spelling were statistically significant predictors of Chinese word reading. This implies that oral vocabulary accounted for a large amount of variance in common with both phonological awareness and tone identification, but not to the same extent with Pinyin initial-final spelling so that a unique amount of variance in Chinese word reading was accounted for by Pinyin initial-final spelling.

The second research question asked the following: What is the relative importance of the code- and meaning-related skills (i.e., Pinyin initial-final spelling, phonological awareness vs. tone awareness, oral vocabulary) in Chinese word reading? Because of the interrelation of the variables, eta squared estimation and dominance analysis were used to calculate the unique and average contribution of each predictor in Model 3, the better specified model, which provides more accurate estimates for inferences than the other two less specified models (Box, 1976). Oral vocabulary made the largest unique and shared contribution to accounting for variability in Chinese word reading (see Table 4). Tone identification did not account for a significantly unique amount of variance in Chinese word reading after accounting for the effects of the two code-related variables and oral vocabulary. However, tone identification made the second largest amount of shared contribution to Chinese word reading. The two code-related predictors explained 12% and 6%, respectively, of shared variance in Chinese word reading. Only Pinyin initial-final spelling explained a unique amount of variance in Chinese word reading after accounting for oral vocabulary, tone identification, and phonological awareness.

Model checking on the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity of the models did not indicate extreme violations of the assumptions. The multicollinearity of the models was tested, and the variance inflation factors (VIF) for all variables were below 3 (see Table 3), which was considered small (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013).

Discussion

The present study investigated the unique and average contributions of the two separate Pinyin skills and oral vocabulary to explaining variability in Chinese word reading in third-grade MI students. Multiple regression and variance analyses together showed that while both oral vocabulary and Pinyin initial-final spelling made statistically significant and unique contributions to Chinese word reading, oral vocabulary and tone identification could explain more shared variance than the code-related skills in Chinese word reading.

First, oral vocabulary had the strongest predictive strength to predict Chinese word reading for Chinese L2 learners in the present study. This result is consistent with previous studies of Chinese L1 and L2 children at similar grade levels (Huang & Hanley, 1995; Zhou & McBride, 2015). The relative importance of meaning-related skill of oral vocabulary may be explained by the nature of the orthography. Reading and spelling alphabetic languages may primarily depend on the ability to segment phonological elements, especially in early stages of development (Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). However, the deep orthography of Chinese characters is only decodable at the syllabic level and naming a character does not need to identify the phonological elements within a tonal syllable (Read et al., 1986). Additionally, semantic knowledge has been found to be causally related to Chinese reading (e.g., Wu et al., 2009; Zhang, Duff, & Hulme, 2015). Together with the findings in previous studies, the results of the present study suggests that semantic knowledge may aid in the storage and retrieval of phonology from orthography, based on the triangle model (Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989). This is also in accordance with the common pedagogical practice of associating the meaning of a character or a word with its form and sound (Wu et al., 2009).

This study addresses a gap in the current literature by exploring the nature of the two separate Pinyin skills: Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification. The findings confirmed the hypothesis that tone identification was related to but different from Pinyin initial-final spelling. The evidence of the high correlations of tone identification with oral vocabulary and with code-related skills suggests that the nature of the construct of tone awareness involves both meaning and phonology and meaning may be an important factor for Chinese L2 learners to accurately identify the tone of a syllable. Similar to Chinese L1 children in Hua and Dodd (2000), the MI third graders in the present study could produce highly accurate tones when reading isolated Chinese words, but they may need a much longer time to develop stronger tone sensitivity than their Chinese L1 peers. The high correlations between tone identification and oral vocabulary may indicate a bidirectional relationship. Students who have better oral vocabulary may develop more advanced tone sensitivity. On the other hand, better tone sensitivity may also be reflected as an advantage of oral vocabulary (Tong et al., 2015). Both of the two meaning-related factors may facilitate character literacy development (McBride-Chang et al., 2008; Tong et al., 2015, 2017).

In addition, although tone identification was not a significant predictor of Chinese word reading, its shared predictive value was larger than the code-related measures. Tone identification could also account for the variance explained by the two code-related skills in the study. Thus, the findings suggest that some of the predictive effect of the holistic Pinyin spelling in previous studies (Lin et al., 2010; Lü, 2017; Zhang & Roberts, 2020) may partially come from combining the two separate Pinyin skills and/or the omission of other meaning-related constructs (e.g., oral vocabulary, morphological awareness) in the models.

Pinyin initial-final spelling accounted for unique variance in Chinese word reading, after removing the effects of tone identification, phonological awareness, and oral vocabulary. Because most Pinyin initials and finals have a one-to-one correspondence to Chinese sounds, Pinyin initial-final spelling can be interpreted as learning the mapping between Pinyin graphemes and Chinese sounds. The unique predictive effect of Pinyin initial-final spelling may suggest that students who had better Pinyin letter knowledge can read more Chinese words. As earlier studies suggested, the strong correlation between decoding Chinese and English words in the students who learned English as L2 in Hong Kong may be related to the use of similar learning strategies and instructional methods in learning the two typologically different orthographies (Bialystok et al., 2005; Keung & Ho, 2009; Zhou et al., 2017). The unique contribution of Pinyin initial-final spelling to Chinese word reading may be explained by the fact that these MI students learned Pinyin and Chinese characters in the same classrooms with the same teachers who used a number of memorization and repetition activities to teach Pinyin and Chinese characters.

The findings in the present study differ from Zhou and McBride (2015) who found that Pinyin initial-final spelling was not significantly associated with Chinese word reading in Chinese L2 children, but tone identification was. This difference in the results may be due to differences between the two studies in students’ characteristics and educational experiences. One of the most important differences was the different developmental stages the students were tested at. In Zhou and McBride (2015), the students had been introduced to Pinyin for four years, both native and nonnative Chinese speaking students were fairly proficient at Pinyin spelling, and they did not differ in Pinyin initial-final spelling proficiency. However, in the present study, this group of third grade MI students had been taught Pinyin for less than one academic year and their Pinyin spelling skill was still low. Additionally, Zhou and McBride (2015) also included two additional predictors in their model, including rapid automatized naming that requires the retrieval of the visual print and backward digit recall that assesses working memory, both of which may confound the relationship between Pinyin initial-final spelling and Chinese word reading.

The present study showed that the two separate Pinyin skills each had significant correlations with phonological awareness and the variance in Chinese word reading explained by phonological awareness can be accounted for by the two separate Pinyin skills. The results may suggest that the Pinyin spelling measures have the potential to assess Chinese phonological awareness, as argued in the previous studies with Chinese L1 and Chinese L2 learners (Ding et al., 2015; Zhang & Roberts, 2020). However, it is important to note that the prediction of Chinese word reading by Pinyin skills may not fully represent the relationship between phonological awareness and Chinese word reading because some variance explained by the Pinyin skills may not be explained by phonological awareness. Therefore, it is necessary to acknowledge other possible confounding factors when replacing phonological awareness with the measure of Pinyin spelling to predict Chinese word reading.

The present study did not include other meaning-related measures, such as lexical (character) and sublexical (semantic radical) level morphological skills, which may also confound the interrelations of the identified variables. However, omitting morphological awareness may be appropriate for the participants in the present study for three reasons. First, the students in the participating schools were usually introduced to words as holistic meaning concepts, instead of providing explanations of the meaning of individual characters. Second, morphological awareness tasks can be confounded by students’ listening comprehension. For example, in Zhou’s (2012) dissertation study, the Chinese L2 children hardly understood the instructions for the task. Third, lexical and sublexical level morphological awareness could make contributions to Chinese word reading through the mediation of oral vocabulary (Tong et al., 2017).

Implications

The findings of the present study, together with those of previous studies on Chinese L1 children (McBride-Chang et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2011; Shu et al., 2006) and on Chinese L2 children (Wong, 2017; Zhou & McBride, 2015), suggest that semantic knowledge is of critical importance in teaching and learning Chinese for Chinese L2 children. Oral vocabulary has been found to have correlational and causal relationships with Chinese word reading (Chow et al., 2008; Wang & McBride, 2016; Wu et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2015). The role of oral vocabulary might be particularly important for Chinese L2 learners because their Chinese language skills may not be as robust as Chinese L1 learners (Zhou & McBride, 2015). This is especially true for learning the large number of complex and abstract words they encounter at higher grade levels, known as Tier Two words (Beck et al., 2002). Rote memorization and repetition exercises may not be effective for Chinese L2 learners to learn thousands of characters, even over the course of several years. Teachers need to design instructional activities to help students understand and internalize the meaning of new words at the same time they are doing reading and writing activities. In all, more attention should be paid to meaning-related assessments and interventions in research studies, as well as pedagogical and clinical practices designed to promote Chinese character literacy development in Chinese L1 and L2 learners.

The findings in the present study suggest that code-related skills may not be as important as meaning-related skills in Chinese word reading for MI learners. The strong predictive effect of phonological awareness on early Chinese reading found in prior studies may be confounded by the multidimensional phonological construct that taps into a general cognitive ability, verbal memory, and speech perception ability (McBride-Chang, 1995). Although the two separate Pinyin skills may gauge Chinese phonological awareness to predict Chinese word reading, a causal link between phonological awareness and Chinese word reading has not been established in Chinese reading acquisition (McBride & Wang, 2015; Zhou et al., 2012). Therefore, it is inappropriate to interpret the correlation between Pinyin skills or Chinese phonological awareness and Chinese character or word reading to indicate a causal effect. Future experimental studies are needed to test if training on phonological awareness or Pinyin spelling skills promotes Chinese word reading in comparison to a control group. Another ongoing query is whether or not the use of Pinyin caption can promote Chinese word reading, which is also an experimental question that cannot be answered by the present study.

The deep orthography of Chinese provides an opportunity to examine the pathways between phonology, orthography, and semantics in the reading model proposed by Seidenberg and McClelland (1989). Ricketts et al. (2007) evidenced that English-speaking children relied on a semantic pathway (i.e., oral vocabulary) in reading irregular English words, compared to the reliance on a phonological pathway for consistent mappings between orthography and phonology. Chinese characters do not have phonemic or tone representations in the orthography, and the majority of phonetic components are not reliable cues for the pronunciation of characters (Shu et al., 2003). The importance of morphological awareness, oral vocabulary, and tone sensitivity, broadly defined as meaning-related skills, has shown significant influence on the learning of the deep orthography of Chinese in comparison to code-related skills. The present study makes a special contribution in examining the hypothesis of a semantic pathway in English-speaking children who learn Chinese as a L2. However, the present study only recruited students at one academic grade in an early total MI program in the U.S. Future longitudinal research is needed to examine the developmental patterns of meaning- and code-related skills across early and later literacy development in Chinese L1 learners who are introduced to Pinyin in Grade 1 from Chinese-speaking societies and Chinese L2 learners who are introduced to Pinyin at various academic grades in a variety of foreign language and bilingual educational contexts.

Conclusion

Based on the results from 70 third graders who were introduced to Pinyin system at Grade 3 in a U.S. MI program, the present study found that both oral vocabulary and Pinyin initial-final spelling explained a unique amount of variance in Chinese word reading above and beyond that explained by phonological awareness and tone identification. Additionally, oral vocabulary made the largest unique and shared contribution to explaining variance in Chinese word reading. The ability to identify tones required in Chinese word reading was fully accounted for by oral vocabulary and the code-related measures of phonological awareness and Pinyin initial-final spelling. Although tone identification did not make a unique contribution to Chinese word reading in the final model, it may make a contribution to Chinese word reading through shared variance with oral vocabulary, Pinyin initial-final spelling, and phonological awareness. The tasks of Pinyin initial-final spelling and tone identification represent meaningful ways to measure Chinese phonological awareness at segmental and supersegmental levels. The study underscores the importance of meaning-related skills in learning to read the opaque orthography of Chinese for MI young learners who learn Chinese as a L2.

Code availability

The custom code in R language that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Data availability

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Anderson, R. C., Ku, Y., Li, W., Chen, X., Wu, X., & Shu, H. (2013). Learning to see the patterns in Chinese characters. Scientific Studies of Reading, 17(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2012.689789

Anderson, R. C., & Li, W. (2006). A cross-language perspective on learning to read. In A. McKeough, L. Phillips, V. Timmons, & J. L. Lupart (Eds.), Understanding literacy development: A global view (pp. 65–91). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

August, D. E., & Shanahan, T. E. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the national literacy panel on language-minority children and youth. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Beck, I., McKeown, M., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. The Guilford Press.

Bialystok, E., McBride-Chang, C., & Luk, G. (2005). Bilingualism, language proficiency, and learning to read in two writing systems. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 580–590. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.4.580

Box, G. E. P. (1976). Science and statistics. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 71, 791–799. https://doi.org/10.2307/2286841

Budescu, D. V. (1993). Dominance analysis: A new approach to the problem of relative importance of predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 542–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.542

Burkhauser, S., Steele, J. L., Li, J., Slater, R. O., Bacon, M., & Miller, T. (2016). Partner-language learning trajectories in dual-language immersion: Evidence from an urban district. Foreign Language Annals, 49, 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12218

Campbell, R. (1985). When children write nonwords to dictation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 40, 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0965(85)90069-4

Chow, B. W.-Y., McBride-Chang, C., Cheung, H., & Chow, C. S.-L. (2008). Dialogic reading and morphology training in Chinese children: Effects on language and literacy. Developmental Psychology, 44, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.233

Committee of Chinese Writing System Reform. (1958). Scheme of the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.cn/ewebeditor/uploadfile/2015/03/02/20150302165814246.pdf

Ding, Y., Liu, R.-D., McBride, C., & Zhang, D. (2015). Pinyin invented spelling in Mandarin Chinese-speaking children with and without reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48, 635–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219414522704

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). PPVT-4: Peabody picture vocabulary test. Pearson Assessments.

Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T. (2001). Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the national reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Reading research quarterly, 36(3), 250–287. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.36.3.2

Everson, M. E. (1998). Word recognition among learners of Chinese as a foreign language: Investigating the relationship between naming and knowing. The Modern Language Journal, 82, 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01192.x

Fortune, T. W., & Song, W. (2016). Academic achievement and language proficiency in early total Mandarin immersion education. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 4, 168–197. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.4.2.02for

Fortune, T. W., & Tedick, D. J. (2003). What parents want to know about foreign language immersion programs. Retreived from https://carla.umn.edu/immersion/FAQs.html

Frost, R., Katz, L., & Bentin, S. (1987). Strategies for visual word recognition and orthographical depth: A multilingual comparison. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 13(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.13.1.104

Genesee, F. (2004). What do we know about bilingual education for majority language students? In T. K. Bhatia & W. Ritchie (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism and multiculturalism (pp. 547–576). Blackwell.

Hamayan, E., Genesee, F., & Cloud, N. (2013). Dual language instruction from a-z: Practical guidance for teachers and administrators. Heinemann.

Ho, C. S.-H., & Bryant, P. (1997). Development of phonological awareness of Chinese children in Hong Kong. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 26, 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025016322316

Hua, Z., & Dodd, B. (2000). The phonological acquisition of Putonghua (Modern Standard Chinese). Journal of Child Language, 27(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/s030500099900402x

Huang, H. S., & Hanley, J. R. (1995). Phonological awareness and visual skills in learning to read Chinese and English. Cognition, 54(1), 73–98.

Hulme, C., Zhou, L., Tong, X., Lervåg, A., & Burgoyne, K. (2019). Learning to read in Chinese: Evidence for reciprocal relationships between word reading and oral language skills. Developmental science, 22(1), e12745. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12745

Katz, L., & Frost, R. (1992). The reading process is different for different orthographies: The orthographic depth hypothesis. In R. Frost & L. Katz (Eds.), Orthography, phonology, morphology, and meaning (pp. 67–84). North Holland.

Keung, Y. C., & Ho, C. S.-H. (2009). Transfer of reading-related cognitive skills in learning to read Chinese (L1) and English (L2) among Chinese elementary school children. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.11.001

Koda, K., & Zehler, A. M. (Eds.). (2008). Learning to read across languages: Cross-linguistic relationships in first-and second-language literacy development. Routledge.

Kuo, L. J., & Anderson, R. C. (2006). Morphological awareness and learning to read: A cross-language perspective. Educational Psychologist, 41, 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4103_3

Levine, T. R., & Hullett, C. R. (2002). Eta squared, partial eta squared, and misreporting of effect size in communication research. Human Communication Research, 28, 612–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00828.x

Li, C., & Thompson, S. A. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. University of California Press.

Li, W.-S., & Ho, C. S.-H. (2011). Lexical tone awareness among Chinese children with developmental dyslexia. Journal of Child Language, 38, 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000910000346

Lin, D., McBride-Chang, C., Shu, H., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Zhang, J., Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2010). Small wins big: Analytic Pinyin skills promote Chinese word reading. Psychological Science, 21, 1117–1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610375447

Lin, Y.-W. (2007). The sounds of Chinese. Cambridge University Press.

Lindholm-Leary, K. J. (2001). Dual language education. Multilingual Matters.

Lü, C. (2017). The roles of Pinyin skill in English-Chinese biliteracy learning: Evidence from Chinese immersion learners. Foreign Language Annals, 50, 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12269

Mandarin Immersion Parents Council. (2020). Full Mandarin immersion school list [Data file]. Retrieved from https://miparentscouncil.org/full-mandarin-immersion-school-list/

McBride, C. (2016). Children’s literacy development: A cross-cultural perspective on learning to read and write. Routledge.

McBride, C., & Wang, Y. (2015). Learning to read Chinese: Universal and unique cognitive cores. Child Development Perspectives, 9, 196–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12132

McBride-Chang, C. (1995). What is phonological awareness? Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2017.11.001

McBride-Chang, C. (1998). The development of invented spelling. Early Education & Development, 9, 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed0902

McBride-Chang, C., Cho, J. R., Liu, H., Wagner, R. K., Shu, H., Zhou, A., Cheuk, C. S.-M., & Muse, A. (2005). Changing models across cultures: Associations of phonological awareness and morphological structure awareness with vocabulary and word recognition in second graders from Beijing, Hong Kong, Korea, and the United States. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 92, 140–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2005.03.009

McBride-Chang, C., & Ho, C. S.-H. (2005). Predictors of beginning reading in Chinese and English: A 2-year longitudinal study of Chinese kindergartners. Scientific studies of Reading, 9(2), 117–144. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_2

McBride-Chang, C., Tong, X., Shu, H., Wong, A. M. Y., Leung, K. W., & Tardif, T. (2008). Syllable, phoneme, and tone: Psycholinguistic units in early Chinese and english word recognition. Scientific Studies of Reading, 12, 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430801917290

Pan, J., McBride-Chang, C., Shu, H., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., & Li, H. (2011). What is in the naming? A 5-year longitudinal study of early rapid naming and phonological sensitivity in relation to subsequent reading skills in both native Chinese and English as a second language. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 897–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024344

Perfetti, C. A. (2003). The universal grammar of reading. Scientific studies of reading, 7(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532799XSSR0701_02

Rayner, K., Foorman, B. R., Perfetti, C. A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2001). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2(2), 31–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.00004

Read, C., Zhang, Y., Nie, H., & Ding, B. (1986). The ability to manipulate speech sounds depends on knowing alphabetic spelling. Cognition, 24(1–2), 31–44.

Ricketts, J., Nation, K., & Bishop, D. V. M. (2007). Vocabulary is important for some, but not all reading skills. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11, 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430701344306

Seidenberg, M. S., & McClelland, J. L. (1989). A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychological Review, 96, 523–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.523

Selkirk, E. (1982). The syllable. In H. V. D. Hulst & N. Smith (Eds.), The structure of phonological representations: Part 2 (pp. 337–384). Foris.

Seymour, P. H. K., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94(2), 143–174. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712603321661859

Shu, H., & Anderson, C. (1997). Role of radical awareness in the character and word acqusition of Chinese chilren. Reading Research Quarterly, 32(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.32.1.5

Shu, H., Chen, X., Anderson, R. C., Wu, N., & Xuan, Y. (2003). Properties of school Chinese: Implications for learning to read. Child Development, 74(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00519

Shu, H., McBride-Chang, C., Wu, S., & Liu, H. (2006). Understanding Chinese developmental dyslexia: Morphological awareness as a core cognitive construct. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.122

Shu, H., Peng, H., & McBride-Chang, C. (2008). Phonological awareness in young Chinese children. Developmental Science, 11, 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00654.x

Swender, E., Conrad, D. J., & Vicars, R. (2012). ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines 2012. Retrieved from https://www.actfl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/public/ACTFLProficiencyGuidelines2012_FINAL.pdf

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

Tong, X., Tong, X., & McBride, C. (2017). Unpacking the relation between morphological awareness and Chinese word reading: Levels of morphological awareness and vocabulary. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.07.003

Tong, X., Tong, X., & McBride-Chang, C. (2015). Tune in to the tone: Lexical tone identification is associated with vocabulary and word recognition abilities in young Chinese children. Language and Speech, 58, 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830914562988

Wang, Y., & McBride, C. (2016). Character reading and word reading in Chinese: Unique correlates for Chinese kindergarteners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 37, 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1017/S014271641500003X

Watzinger-Tharp, J., Rubio, F., & Tharp, D. S. (2018). Linguistic performance of dual language immersion students. Foreign Language Annals, 51, 575–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12354

Williams, K. T. (2007). EVT-2: Expressive vocabulary test, form A (2nd ed.). Pearson Assessments.

Wong, Y. K. (2017). The role of radical awareness in Chinese-as-a-second-language learners’ Chinese character reading development. Language Awareness, 26(3), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2017.1400039

Wu, X., Anderson, R. C., Li, W., Wu, X., Li, H., Zhang, J., Zheng, Q., Zhu, J., Shu, H., Jiang, W., Chen, X., Wang, Q., Yin, L., He, Y., Packard, J., & Gaffney, J. S. (2009). Morphological awareness and Chinese children’s literacy development: An intervention study. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(1), 26–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430802631734

Yeung, P.-S., Ho, C. S.-H., Wong, Y.-K., Chan, D. W.-O., Chung, K. K.-H., & Lo, L.-Y. (2013). Longitudinal predictors of Chinese word reading and spelling among elementary grade students. Applied Psycholinguistics, 34, 1245–1277. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716412000239

Zhang, H. (2016). Morphological awareness in literacy acquisition of Chinese second graders: A path analysis. Journal of psycholinguistic research, 45(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-014-9327-1

Zhang, H., & Koda, K. (2018). Vocabulary knowledge and morphological awareness in Chinese as a heritage language (CHL) reading comprehension ability. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 31, 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9773-x

Zhang, H., & Roberts, L. (2020). A comparison of Pinyin invented spelling and oddity test in measuring phonological awareness in L2 learners of Chinese. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 3, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09700-z

Zhang, Y., Tardif, T., Shu, H., Li, H., Liu, H., McBride-Chang, C., Liang, W., & Zhang, Z. (2013). Phonological skills and vocabulary knowledge mediate socioeconomic status effects in predicting reading outcomes for Chinese children. Developmental Psychology, 49, 665–671. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028612

Zhou, L., Duff, F. J., & Hulme, C. (2015). Phonological and semantic knowledge are causal influences on learning to read words in Chinese. Scientific Studies of Reading, 19, 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2015.1068317

Zhou, Y. (2012). An investigation of cognitive, linguistic and reading correlates in children learning Chinese and English as a first and second language. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Zhou, Y., & McBride, C. (2015). The same or different: An investigation of cognitive and metalinguistic correlates of Chinese word reading for native and non-native Chinese speaking children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21(4), 765–781.

Zhou, Y., McBride, C., Leung, J. S. M., Wang, Y., Joshi, M., & Farver, J. (2017). Chinese and english reading-related skills in L1 and L2 Chinese-speaking children in Hong Kong. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 33, 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2017.1342848

Zhou, Y., McBride-Chang, C., Fong, C. Y.-C., Wong, T. T.-Y., & Cheung, S. K. (2012). A comparison of phonological awareness, lexical compounding, and homophone training for Chinese word reading in Hong Kong kindergartners. Early Education & Development, 23, 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2010.530478

Ziegler, J. C., Bertrand, D., Tóth, D., Csépe, V., Reis, A., Faísca, L., & Saine, N., Lyytinen, H., Vaessen, A., Blomert, L. (2010). Orthographic depth and its impact on universal predictors of reading: A cross-language investigation. Psychological science, 21, 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610363406

Ziegler, J. C., & Goswami, U. (2005). Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages: A psycholinguistic grain size theory. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.3

Ziegler, J. C., & Goswami, U. (2006). Becoming literate in different languages: similar problems, different solutions. Developmental science, 9, 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00509.x

Funding

The study reported in this article received financial support from Language Learning and the National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations/National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author or corresponding author is the major contributor of the study. The second and third authors have been deeply involved in all aspects of the study, including study design, material preparation, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ju, Z., Zhou, Y. & delMas, R. The contributions of separate pinyin skills and oral vocabulary to Chinese word reading of U.S. Mandarin immersion third graders. Read Writ 34, 2439–2459 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10150-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10150-9