Abstract

Nonrecurring income taxes are transitory items that exclusively affect earnings through tax expense. We conduct the first in-depth examination of nonrecurring income taxes to determine whether they are primarily attributable to economic events or managerial opportunism. We find that nonrecurring income taxes have little predictive power for future earnings, are not associated with meeting or beating analyst earnings forecasts, and are not associated with future tax expense restatements. We also provide descriptive information about the tax events that frequently result in nonrecurring income taxes and find that the most common events are tax audit resolutions, valuation allowance changes, tax law changes, mergers, and repatriations. Overall, our findings suggest that nonrecurring income taxes are driven by economics rather than opportunism. We recommend that researchers consider whether the inclusion of nonrecurring income taxes (or specific types of nonrecurring taxes) is appropriate when using effective tax rate levels or volatility as measures of tax risk, avoidance, or aggressiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

We conduct the first in-depth examination of nonrecurring income tax items, which we define as one-time events that exclusively affect earnings through tax expense. Identifying nonrecurring items is important for analysts, investors, and academics attempting to forecast earnings. Early research on nonrecurring items focused on special items, which exclude tax-specific items. Over time, the literature expanded to include non-GAAP disclosures. Managers commonly adjust non-GAAP earnings for one-time tax items, and most studies view tax adjustments as opportunistic (e.g., Black et al. 2017). As such, we examine whether nonrecurring income taxes primarily reflect economic events or managerial opportunism.

We first describe the frequency and nature of nonrecurring tax items, using Compustat’s identification of a nonrecurring tax (NRTAX) item. As expected, the frequency increases in firm size, reflecting firm complexity. We use a large subsample of hand-collected data to identify the most common sources of NRTAX: resolutions of tax audits, valuation allowance changes, tax law changes, mergers, and repatriations. These sources appear to reflect economic events but also require some managerial judgment. We thus initially examine the circumstances in which nonrecurring taxes are explainable or predictable.

At the outset, we note that it is difficult to predict nonrecurring tax items, and this difficulty is compounded by the fact that the events triggering these items are often firm-specific. For example, it is difficult for outsiders to predict whether a firm will repatriate earnings, release a valuation allowance, or conclude a tax audit. Thus, it is challenging to identify nonrecurring tax items in a specific period without guidance from management or a country-level event.Footnote 1 However, such events are eventually more likely for firms with substantial permanently reinvested earnings (PRE), deferred tax balances, or ongoing tax audits. We find that several economic and financial variables explain concurrent NRTAX amounts, including changes in deferred tax assets/liabilities, PRE, changes in quarterly ETRs, changes in sales, return on assets and book-to-market ratio. However, these same variables only weakly predict NRTAX amounts in the next quarter, consistent with unpredictable economic events driving NRTAX.

We also examine the correlation between special items and nonrecurring income taxes. Like our definition of nonrecurring income tax items, Compustat’s NRTAX does not include tax effects of special items, so a significant correlation between special items and NRTAX does not suggest a mechanical relationship. Rather, it suggests that similar events lead firms to recognize special items and NRTAX simultaneously. We find a significant, positive correlation between nonrecurring income taxes and special items, but it is economically small (ρ = 0.04), consistent with our hand-collected data showing that the economic events that generate most nonrecurring income taxes are unrelated to the events driving special items. We also find that negative special items and income-decreasing nonrecurring taxes are positively correlated (ρ = 0.40). Although this group represents only 1.5% of the sample, the finding suggests that negative economic events can generate special items and nonrecurring taxes, such as when firms simultaneously impair goodwill and initiate a valuation allowance on deferred tax assets.

Given these descriptive results, we perform a battery of tests to assess the degree of opportunism in disclosing tax events that Compustat identifies as NRTAX. Our results suggest that managers do not generally manage earnings with nonrecurring income taxes. We base this conclusion on the failure to find evidence regarding NRTAX that is consistent with several key findings from the special items literature (Cain et al. 2019), along with additional tests.

We first summarize several findings regarding the relation between nonrecurring taxes, earnings, and tax expense. First, nonrecurring taxes predict future cumulative operating earnings in the next four quarters more weakly than special items, but nonrecurring taxes do not predict future Street earnings or GAAP tax expense. The lack of a link to Street earnings argues against a connection to managerial opportunism. Second, we do not find a significant association between NRTAX and meeting or beating future analyst earnings forecasts. Third, we do not find that nonrecurring income taxes are associated with restatements of tax expense. Fourth, quarterly ETRs adjusted to exclude nonrecurring taxes are relatively stable, suggesting that, unlike special items, managers do not use nonrecurring income taxes to shift expenses between periods.

With respect to market responses, we find little reaction to nonrecurring taxes at the earnings release, but the market does react over the quarter. This finding is consistent with managers voluntarily informing investors about nonrecurring taxes. In annual return tests, we find significant associations between stock returns and NRTAX, even after controlling for the proxies of individual components of NRTAX (e.g., change in deferred tax assets) that explain some of the incidence and amount of NRTAX. In sum, market reactions suggest that managers disclose nonrecurring taxes in a timely manner, consistent with an intent to inform investors. Further, NRTAX provides investors incremental information beyond the proxies of its individual components. Overall, our findings regarding earnings and market reactions are more consistent with nonrecurring taxes being primarily driven by economic events rather than opportunism.

Although predicting the timing and amount of nonrecurring income taxes is generally difficult, major tax law changes can generate nonrecurring income taxes that materially affect the earnings of many firms. We examine nonrecurring income taxes from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) as an example and find that the amount of TCJA’s NRTAX was very predictable in the fourth quarter of 2017 (once the law was passed), based on beginning-of-year indefinitely reinvested foreign earnings and beginning-of-quarter deferred tax assets and liabilities.

Our study contributes to the literature by showing that nonrecurring tax items are both material and complex. The limited knowledge of one-time tax items could contribute to why previous studies of special items ignore them and why studies of non-GAAP earnings classify them as opportunistic. Our findings are more consistent with economic factors driving nonrecurring tax items, although any item can contain traces of managerial opportunism. This is similar to prior research regarding special items (Donelson et al. 2011). Our results also suggest that future research regarding transitory items should expand its focus to include nonrecurring income taxes.

We also contribute to the nascent literature examining tax forecasting (Bratten et al. 2017; Mauler 2019) and managers’ voluntary tax disclosures (Chen et al. 2020; Ehinger et al. 2020; Koutney 2021). We recommend that researchers carefully consider their individual research questions and whether removing nonrecurring taxes is appropriate in their research settings. For example, we show that researchers need to examine the impact of nonrecurring income taxes when they use GAAP ETR forecasts or ETRs as proxies for tax avoidance, due to nonrecurring tax items’ ability to strongly influence these metrics and the fact that nonrecurring taxes are primarily influenced by economic factors.

We thus recommend, as examples, that researchers examine whether removing nonrecurring tax items affects their conclusions when using ETR levels or volatility as measures of tax risk and avoidance or aggressiveness. If a certain type of firm has high ETR volatility when nonrecurring tax items are included but has normal ETR volatility after they are removed, researchers could examine whether the firm’s type is related to generating more nonrecurring income taxes. In addition, we find that 1-year GAAP ETRs are more representative of long-run tax avoidance if they exclude NRTAX. Specifically, we find moderate increases in the correlation coefficient between 1-year GAAP ETRs and 5-year cash ETRs after excluding NRTAX (from 0.23 correlation for unadjusted GAAP ETRs to 0.26 for adjusted GAAP ETRs), with the greatest increase in correlations for the largest firms. Overall, researchers should consider whether their research question relates to firms having substantial changes in UTBs or valuation allowances.

2 Literature review

We intend this study to describe nonrecurring income taxes to guide future research. Given the length of the empirical analysis, we first briefly describe prior work in two areas: 1) special items and non-GAAP adjustments generally, and 2) discrete tax items.

2.1 Special items and non-GAAP adjustments

Research on transitory items often uses special items identified by Compustat (Cready et al. 2010, 2012; Curtis et al. 2014; Jones and Smith 2011). Burgstahler et al. (2002) and Fairfield et al. (2009) provide evidence that special items predict future earnings. That is, the economic conditions that lead to a (typically income-decreasing) special item in one period may persist to another period, and firms may stay in a similar economic condition for some period of time. However, Frankel (2009) argues that special items should be considered transitory because their predictive power is small. In addition, analysts distinguish special items from other earnings components, and investors adjust for them in valuation (e.g., Burgstahler et al. 2002; Curtis et al. 2014), consistent with analysts and investors treating special items as transitory on average.

Despite decades of research on transitory items, the literature does not provide direct evidence on one-time tax items. Compustat defines special items (SPI) as unusual or nonrecurring items presented before taxes, so SPI excludes one-time tax items by definition. In addition, our conversations with S&P Client Relations confirm that SPI excludes our measure of one-time tax items (NRTAX). Thus, based on the special item literature, we do not have evidence that findings about special items apply (or do not apply) to one-time tax items. However, some research in the non-GAAP earnings literature suggests that one-time tax items are substantially different from special items, as we discuss next.

Most managers now issue non-GAAP earnings (Audit Analytics 2018), which are GAAP earnings adjusted for certain earnings items that managers deem less informative for investors, such as transitory items or non-cash expenses. The non-GAAP earnings literature examines one-time tax items somewhat indirectly, by examining the difference between non-GAAP and GAAP earnings. These studies often examine whether non-GAAP earnings adjustments reflect managerial opportunism and the extent to which analysts and investors understand adjustments.

Doyle et al. (2003) find that exclusions of other types of income-decreasing items that are not special items (“other exclusions”) predict future cash flows. Further, Doyle et al. (2013) find that managers opportunistically use other exclusions in non-GAAP earnings to beat analyst expectations. As one-time tax items are not special items, they fit in the Doyle et al. (2003, 2013) classification of other exclusions, implying that managers use them opportunistically.

Other studies conclude that managers opportunistically report one-time tax items and are inconsistent about whether such items are transitory. Black and Christensen (2009, 316) find that managers use “opportunistic adjustments” through tax items “to convert a GAAP operating loss to a pro forma profit.” Similarly, Black et al. (2017, 231) state that “managers … are more likely to utilize certain recurring exclusions such as … tax … to meet their opportunistic motivations.” In addition, Christensen et al. (2014) find that tax items represent 21.6% of managers’ recurring items adjustments (358 out of 1,661 total items) between 1998 and 2003, but Black et al. (2018, 2021) classify tax adjustments as nonrecurring. Thus, there is some controversy regarding whether non-GAAP tax items are transitory. Our tests provide evidence about the extent to which nonrecurring income tax items are transitory, and about whether they appear opportunistic.

2.2 Nonrecurring versus discrete tax items

Nonrecurring income taxes have some overlap with ASC 740’s discrete items. ASC 740-270 codifies Accounting Principles Board Opinion No. 28 to guide interim reporting of income tax. Section 30-1 instructs firms to estimate an annual ETR and apply it to ordinary income or loss to determine interim period income tax expense or benefit. This accounting follows the theory that the quarter is integral to the year, and is thus called the “integral method.” Practitioners refer to items not accounted for under the integral method as “discrete items.”Footnote 2

Section 30-7 states that the estimated annual ETR should include the tax effect of any valuation allowance (VA) that is expected to be needed at year-end, expected foreign tax rates, credits, and other tax planning.Footnote 3 However, the estimated annual ETR excludes “the effects of changes in judgment about beginning-of-year valuation allowances” (Section 30-11). Thus, the creation of a VA is part of the estimated annual ETR, but changing the VA is a discrete item. Similarly, 740-10-25-15 requires that any change in judgment that changes the measurement of a UTB from a prior year “be recognized as a discrete item in the period in which the change occurs.” Finally, Section 30-11 lists changes in tax laws or rates as excluded from the estimated annual ETR.

To sum up, changes in VA, effects of changes in tax laws, and changes in tax reserves (either through judgment or settlements) would be reported as discrete items. Nowhere does it suggest that unusual amounts of tax from operating decisions such as repatriations should be reported as a discrete item under ASC 740. This incomplete overlap between nonrecurring income taxes and discrete tax items is similar to that between Compustat’s SPI and the GAAP definition of significant unusual or infrequently occurring items (Riedl and Srinivasan 2010).

Academic research that focuses specifically on discrete tax items is limited. Bratten et al. (2017) interpret their result that analysts’ forecasts of Street earnings are superior when they deviate from GAAP interim ETRs as consistent with the nonrecurring nature of discrete items. Koutney (2021) investigates determinants of management ETR forecasts and finds that the presence of NRTAX is associated with management issuing an ETR forecast. Mauler (2019) finds that analysts’ tax forecasts are value-relevant to investors, which shows that investors want information about recurring tax expense. However, prior studies show that analysts struggle to incorporate complex tax information into their forecasts (Chen and Schoderbek 2000; Hoopes 2018; Plumlee 2003; Weber 2009). In addition, earnings management increases the complexity of tax information (Comprix et al. 2012; Dhaliwal et al. 2004) through valuation allowance estimates (Bauman et al. 2001; Frank and Rego 2006; Schrand and Wong 2003), permanently reinvested earnings (Krull 2004), and tax contingency reserves (Cazier et al. 2015; Gupta et al. 2016). Our study adds an examination of the specific events that generate differences between Street and GAAP tax expense and of the extent of opportunistic behavior versus disclosure of economic events for tax items.

3 Sample nonrecurring tax (NRTAX) description and disclosure

3.1 Definition of NRTAX

Compustat defines NRTAX as “the amount of income taxes that are reported as nonrecurring by the company or appear to be nonrecurring from the description.” Compustat notes that its definition includes write-offs of deferred tax assets and eliminations of valuation allowances. In discussions with S&P Client Relations, we learned that the amount is gathered by reading “financial statements/notes and the management discussions” and confirmed several other factors that affect the coding of NRTAX. Most importantly, NRTAX is not the tax effect of pre-tax special items (SPIs), and it depends on both materiality and managerial disclosure. Further, any item that appears in three consecutive years will not be considered nonrecurring due to this repetition, and UTB changes are not classified as nonrecurring unless they are identified as so by management. Finally, the disclosure and collection of NRTAX relies on the judgment of both management (disclosure) and Compustat (coding) to ensure that the variable includes amounts that are one-time in nature.

For example, when examining the events that give rise to NRTAX, we found that some firms explicitly describe tax expense items as nonrecurring or discrete tax items or exclude them from their non-GAAP earnings. Other firms disclose the tax item amount with a descriptive reason for the item (e.g., a valuation allowance release) without labelling the item as nonrecurring or discrete. In addition, Compustat’s definition of NRTAX excludes tax benefits from the retroactive extensions of R&D tax credits, which are material to earnings and which some firms describe as unusual or nonrecurring (Kravet et al. 2019). Thus, Compustat does not appear to solely follow firm descriptions to determine NRTAX but rather uses its expertise to identify amounts that are nonrecurring.

3.2 Sample composition

Table 1, Panel A shows the sample selection for the 68,139 observations from 2007 to 2017 Q3 that meet our data requirements. We begin in 2007 so that we can obtain FIN 48 rollforward data; we end in the third quarter of 2017 because TCJA generated substantial nonrecurring income taxes in the fourth quarter of 2017, and nonrecurring income taxes in periods without major tax reform are unlike nonrecurring taxes from TCJA. Panel B shows the number of firm-quarters with non-missing and nonzero NRTAX values. The percentage of firm-quarters with non-missing NRTAX ranges between 8 and 14% for complete fiscal years in column 3, and the percentage of firm-quarters with nonzero NRTAX ranges between 5 and 8% for complete fiscal years in column 5.Footnote 4

Panel C shows the sample industry composition. NRTAX occurs in all industries, with the lowest frequency in healthcare (4.1%) and the highest frequency in chemicals (12.9%). Table 1, Panel D provides the frequency of NRTAX by firm size. Firms in the largest (smallest) size decile have NRTAX in 10.7% (2.8%) of firm-quarters. Thus, the largest firms are four times as likely to have NRTAX as the smallest firms. Larger firms likely have more NRTAX due to their having 1) more tax audit resolutions based on more frequent audits (Mills 1998; Hoopes et al. 2012), 2) repatriations of foreign earnings or tax law changes in various jurisdictions because they are more likely to be multinationals (Krull 2004), 3) valuation allowance releases because they acquire more loss entities through mergers and acquisitions (Mills et al. 2003), 4) more M&A activity (Harford 1999), and 5) more changes in unrecognized tax benefits because they operate in more jurisdictions (Dyreng and Lindsey 2009; Dyreng et al. 2013). Larger firms also generally have better disclosure, are more likely to be able to use acquired NOLs due to the relation between size and profitability, and may receive more careful coding by Compustat.

3.3 Description of nonrecurring income tax and other variables

Table 2, Panel A describes our variables. NRTAX occurs in 6.6% of firm-quarters. On average, NRTAX increases earnings by 3.29% of absolute pretax earnings (the ETR effect) or 0.02% of beginning market value of equity. In contrast, the mean special item is negative and reduces earnings by 31.4% of absolute pretax earnings or 0.41% of beginning market value of equity. In addition, the median nonzero NRTAX is 0.08% of market value of equity, which shows that when NRTAX is present, it usually increases earnings.

Appendix Table 12 defines all variables. Where available, we use quarterly data. However, firms disclose some tax items such as UTB rollforward or PRE amounts only annually. Unless noted, we scale balance sheet and earnings variables by beginning of quarter market value of equity and winsorize variables at the top and bottom one percentile to mitigate the influence of outliers.

Panel B shows univariate correlations as an initial test of whether current quarter tax attributes explain the amount of disclosed current-quarter NRTAX. NRTAX is positively, significantly (ρ = 13.6%) associated with quarterly DTA changes. NRTAX is significantly, negatively associated with DTL changes, but not as substantively (ρ = −1.73%). PRE has a small, negative correlation with NRTAX (ρ = −1.22%). The quarterly difference in the year-to-date ETR (ΔETRq-1,q) is highly, negatively correlated with NRTAX (ρ = −30.0%), which reflects discrete items under ASC 740-270 fully affecting tax expense in the quarter.

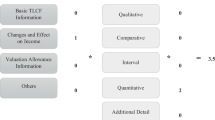

To better understand events generating one-time taxes, we investigate a large subsample of NRTAX. We randomly sample 400 firms with nonzero NRTAX from 2005 to 2012. We identify all quarters in which these firms have NRTAX between 2005 and 2017 Q3, and read the quarterly earnings announcements (8-Ks), interim financial statements (10-Qs), and annual financial statements (10-Ks) from the SEC’s EDGAR database.Footnote 5 Table 3 shows the most common events that generate NRTAX. The two most common are tax audit resolutions (25% of NRTAX) and valuation allowance changes (22%), with most valuation allowance changes due to releases (14%) rather than increases (8%).Footnote 6 Tax law changes account for 8% of NRTAX prior to TCJA. Most of the “other” category mentions multiple events without details about the magnitude of each.Footnote 7

We also show the materiality of the events relative to ETR and firm value. Valuation allowance releases increase earnings by 3.6% of absolute pretax earnings (ETR effect) and are 0.05% of market value. Valuation allowances reduce earnings by 1.3% of absolute pretax earnings and are 0.09% of market value. Although tax audit resolutions are common, their average ETR effect is only 0.3%, while “other” items are only 0.4% of ETR.

3.4 Explaining concurrent disclosure of NRTAX

We estimate a linear probability model of the relation between current quarterly NRTAX and the most recently available financial statement information. Thus, we study whether financial statement tax information provides adequate information about one-time tax items such that users could assess whether managers should have disclosed one-time tax items.Footnote 8

The dependent variable Ind(NRTAXq) equals 1 if NRTAX is nonzero and 0 if NRTAX is zero or missing. NRTAX/Beg MVEq equals the signed amount of nonrecurring income taxes divided by beginning-of-quarter market value of equity. We first discuss tax-related variables that could be associated with the firm having nonrecurring taxes.

For write-offs of deferred tax assets, changes in estimates of deferred tax liabilities, and large valuation allowance changes, we include quarterly changes in deferred tax balances. ΔDTAq-1,q equals the change in the sum of long-term deferred tax assets (TXDBAQ) and current deferred tax assets (TXDBCAQ) from quarter q-1 to quarter q. ΔDTLq-1,q equals the change in the sum of long-term deferred tax liabilities (TXDBQ) and current deferred tax liabilities (TXDBCLQ). We include three indicator variables for the recognition of valuation allowances on deferred tax assets for loss firms (Dhaliwal et al. 2013). BN_VAy-1 equals 1 for loss firm-years with federal deferred taxes (TXDFED) greater than or equal to zero and 0 otherwise in year y-1, and represents loss firms with material increases in valuation allowances. GN_VAy-1 equals 1 for loss firms with negative federal deferred taxes and current federal tax expense (TXFED) less than or equal to zero and 0 otherwise, and represents loss firms without material increases in valuation allowance. GN_TIy-1 equals 1 for loss firms with negative federal deferred taxes and positive current federal tax expense, and represents loss firms that are without material increases in valuation allowance and that pay taxes. We include tax loss carryforwards (TLCFy-1), as firms with carryforwards could have material changes in their estimates of their realizability.

To identify foreign earnings repatriations, we include PREy-1, which equals permanently reinvested earnings (Foreign Earnings from Audit Analytics). To examine changes in estimates in uncertainty about tax positions and resolutions with tax authorities, we include UTB rollforward variables. UTB Increasey-1 equals the increase in UTB from prior period tax positions (TXTUBPOSPINC). UTB Decreasey-1 equals the decrease in UTB from prior period tax positions (TXTUBPOSPDEC). Settlementy-1 is the decrease in UTB due to settlements with tax authorities (TXTUBSETTLE), and Stat of Limity-1 is the decrease in UTB due to a lapse in the statute of limitations (TXTUBSOFLIMIT). We include cash holdings (Cashq) equal to total cash (CHEQ), as firms hold more cash when facing tax uncertainty (Hanlon et al. 2017). We also include R&D expense (RDy-1) equal to research and development expense (XRD), as the research and experimentation credit is a major reason for uncertain tax positions (Towery 2017). Finally, we include the year-to-date change in ETR and annual change in cash ETR. ΔETRq-1,q is the change in the year-to-date GAAP effective tax rate from quarter q-1 to quarter q, where the year-to-date GAAP ETR equals sum of year-to-date GAAP tax expense (TXTQ) divided by the sum of year-to-date pretax earnings (PIQ). ΔCash ETRy-2,y-1 is the annual change in cash effective tax rate from year y-2 to y-1, where cash effective tax rate equals the ratio of cash taxes paid (TXPD) divided by pretax earnings (PI) minus special items (SPI).

Missing values for deferred tax balances, PRE, and UTB rollforward variables are set to zero. We include six indicator variables equal to 1 if we have missing data for PREy-1, UTB Increasey-1, UTB Decreasey-1, Settlementy-1, Stat of Limity-1, and RDy-1 and equal to 0 if we have data. The missing data indicators mitigate concerns that coefficients on the main variables are biased if firms with certain characteristics are more likely to have data. For variables measured annually, we use the most recent available data (the prior fiscal year for fiscal quarters 1, 2, and 3, but the current year for fiscal quarter 4). We also examine the economically driven components of nonrecurring income taxes by including variables that predict the economic component of special items.Footnote 9 We cluster standard errors by firm and scale balance sheet, and earnings-related variables by market value of equity, and include industry, year, and fiscal quarter fixed effects.

Table 4, Panel A shows that current financial statement variables have some explanatory power for concurrent NRTAX. In column 1, changes in deferred tax assets, the bad news for valuation allowances indicator, the level of PRE, and all UTB rollforward variables are significantly, positively associated with Ind(NRTAXq), and R&D expense is negatively associated with Ind(NRTAXq). Some economic variables explain NRTAX incidence, including stock returns over the three quarters prior, return on assets, mergers, decreases in employees, discontinued operations, quarterly pretax losses, longer operating cycles, capital intensity, and firm size.

In column 2, we add the changes in year-to-date ETR and annual cash ETR. To calculate a meaningful ETR, we require positive year-to-date pretax earnings for ETR and positive annual pretax earnings for cash ETR, which reduces the sample size by 40%. Changes in ETR are significantly, negatively associated with the incidence of NRTAX, consistent with more frequent NRTAX items when firms report larger decreases in their ETRs. Annual cash ETR changes are not associated with NRTAX, suggesting that annual changes in cash ETR do not explain quarterly NRTAX. The explanatory power for these models is modest (adjusted R2 of 4.7% and 5.4%).

Columns 3 and 4 show that tax and economic variables provide explanatory power for the contemporaneous amount of NRTAX. Column 3 shows that increases in DTAs are positively associated with NRTAX. This evidence is consistent with, for example, firms recording NRTAX when re-assessing the realizability of DTAs. Reductions in DTLs are negatively associated with NRTAX, but with a smaller magnitude. This suggests that increases in future tax payments reduce current net earnings. We find significant negative coefficients on BN_VA, GN_VA, and GN_TI, suggesting that some loss firms record valuation allowances against deferred tax assets. Higher tax loss carryforwards are positively associated with the amount of nonrecurring taxes, reflecting that some firms release valuation allowances on the carryforwards. We do not find that variables from the UTB rollforward are significantly associated with the amount of NRTAX.

In column 4, we add the change in year-to-date ETR and find that the decline in ETR explains the amount of NRTAX, which makes intuitive sense because discrete tax items are fully recorded in current period tax expense. In column 4’s fully specified model, the explanatory power (adjusted R2) reaches 18.4%. Overall, changes in deferred tax balances, signals about valuation allowances from tax expense, permanently reinvested earnings, and quarterly ETRs are useful in explaining the incidence and amount of NRTAX in the current quarter. Economic variables also have explanatory power, in addition to the tax variables, to explain NRTAX, suggesting that some nonrecurring tax events are economically related.Footnote 10

We examine the performance of the NRTAX incidence model (from column 2 of Panel A) using k-fold cross-validation and comparing the model’s identification of quarterly nonrecurring income taxes to Compustat’s NRTAX coding. We implement a tenfold cross-validation ten times while maintaining the original sample’s proportion of NRTAX in each randomly selected subsample (Larcker and Zakolyukina 2012).Footnote 11 We measure the model’s performance using AUC (area under ROC),Footnote 12 TPR (true positive rate equals the percentage of correctly classified firm-quarters with NRTAX), FPR (false positive rate equals the percentage of incorrectly classified firm-quarters with NRTAX), precision (the percentage of actual firm-quarters with NRTAX among the firm-quarters classified by the model as having NRTAX), and accuracy (the percentage of correctly classified NRTAX firm-quarters). Based on the quarterly prediction NRTAX model, we estimate a score for whether a firm has NRTAX in the firm-quarter, and we classify firm-quarters as having NRTAX if the score is above a given cutoff percentile for the sample, and as not having NRTAX if the score is below that cutoff. We compare Compustat’s NRTAX coding to the model’s predictions on the holdout sample.

Table 4, Panel B shows the model’s performance statistics. The average AUC of the 100 cross-validation runs is 69.0%, which is significantly better than randomness (i.e., the AUC is greater than 50% with p-value < 0.01).Footnote 13 We report the average TPR, FPR, precision, and accuracy at the 85th, 90th, and 95th cutoff percentiles.Footnote 14 At the 95th percentile cutoff, the model has 15.8% TPR, 4.15% FPR, 23.1% precision, and 90.0% accuracy. With lower cutoff values, the classification accuracy declines, but the true positive rate increases. As the true positive rate ranges between 15 and 35%, these results show that although the model has explanatory power for NRTAX (with AUC significantly greater than randomness), NRTAX items are firm-specific and difficult to predict.

To benchmark the explanatory power of the models of current NRTAX, we also model the incidence of current quarterly SPI in Panel C with economic variables. Column 1 shows that the SPI incidence model explains 15.9% of the variation versus the NRTAX incidence model’s adjusted R2 of 5.4%. Column 2 shows the SPI amount model explains 21.4% of the variation versus the NRTAX amount model’s 18.4%.Footnote 15 Thus, economic variables explain more variation for SPI than tax and economic variables explain for NRTAX.

We also investigate Compustat’s NRTAX identification by examining firm-quarters where Compustat and the model disagree about whether the firm-quarter has an NRTAX. First, we examine 50 firm-quarters with the model’s highest prediction values (i.e., the model predicts that the firm-quarter has an NRTAX) but in which Compustat did not record an NRTAX. We identify NRTAX items in 24 of these 50 firm-quarters.Footnote 16 Sixteen of the 24 firms disclose the items in their 10-Q/K rather than in an earnings release, which likely increased Compustat analysts’ difficulty in identifying the items.

We also examine how firms disclose nonrecurring tax items. For example, firms 1) describe tax items with nonrecurring terminology such as “nonrecurring,” “non-cash,” “one-time,” or “discrete,” 2) exclude the tax item from non-GAAP earnings or ETR, or 3) prominently discuss the tax item at the beginning of the earnings announcement. Of the 24 firm-quarters in which Compustat fails to classify a tax item as nonrecurring, we find that six describe the tax items with nonrecurring terminology or discuss them at the beginning of the earnings announcement, but none exclude the item from non-GAAP earnings or ETR. In the remaining 18 firm-quarters, the disclosures only describe the cause for the tax item (leading to potential ambiguity). Thus, Compustat’s coding of NRTAX appears to be most accurate when firms explicitly exclude nonrecurring tax items from their non-GAAP earnings.

Second, we examine 50 firm-quarters with the lowest prediction values (i.e., the model predicts that the firm-quarter does not have an NRTAX) but in which Compustat recorded an NRTAX. The model primarily misses tax audit resolutions (12 firm-quarters), valuation allowances changes (eight firm-quarters), foreign earnings repatriations (seven firm-quarters), and deferred tax asset write-offs (five firm-quarters).Footnote 17 Most firms disclose the NRTAX in their earnings release (41 of the 43 firm-quarters in which we could identify the reason for the NRTAX). We find that 28 firm-quarters exclude the item from non-GAAP earnings, seven label the tax item with nonrecurring terminology, and eight describe the cause for the tax item without highlighting the tax item. Thus, although Compustat uses earnings announcements to identify NRTAX, it also appears to examine 10-Q/Ks and can identify NRTAX regardless of whether the firm describes the item as nonrecurring or excludes the item from non-GAAP earnings.Footnote 18

In Panel D, we adjust the model to explain current incidence and amount of annual NRTAX. We similarly measure all independent variables annually. For brevity, we focus on tax-related variables. In columns 1 and 2, we find that annual changes in deferred tax balances, PRE, and all UTB rollforward variables explain the incidence of the annual NRTAX. R&D expense is negatively associated with the annual NRTAX in column 1. Signals about the valuation allowance (BN_VA and GN_VA) in loss firms are positively associated with annual NRTAX in column 2. We do not find evidence that tax loss carryforwards or cash holdings are associated with NRTAX. Annual changes in the GAAP and cash ETR are not predictive of the incidence of NRTAX.Footnote 19 When explaining the annual amount of NRTAX in columns 3 and 4, some UTB rollforward variables do not provide significant explanatory power, but annual changes in GAAP ETR adds significant explanatory power.

The annual models have explanatory power of 24% and 36% (columns 2 and 4), which is greater than the explanatory power of the quarterly models. However, the tax variables that provide statistically significant explanatory power for NRTAX are similar in both the quarterly and annual models. As such, the higher explanatory power in the annual models can be attributed to the longer period of measurement between the explanatory variables and NRTAX.

3.5 Correlation between NRTAX and SPI

As some economic variables add explanatory power for the incidence and amount of NRTAX, we next examine the correlation between NRTAX and special items. A significant correlation between NRTAX and SPI suggests that economic events can lead firms to record both in the same period. For example, a firm with an unprofitable foreign subsidiary might simultaneously impair goodwill for the subsidiary and initiate a valuation allowance on net operating losses in the foreign country. As NRTAX is not the tax effect of SPI, a significant correlation does not represent a mechanical relationship between SPI and NRTAX.

Table 5 reports the correlations. In the full sample (N = 68,139), we find a statistically significant but economically small correlation between NRTAX and SPI (ρ = 0.04). We examine whether the correlation increases based on whether the special item is income-increasing (i.e., positive) or income-decreasing (i.e., negative). The correlation slightly increases between NRTAX and negative SPI (N = 31,280; ρ = 0.05), and there is not a significant correlation between NRTAX and positive SPI (N = 6,308; ρ = 0.002). The overall significantly positive correlation between NRTAX and SPI appears to be driven by firm-quarters with income-decreasing NRTAX and negative SPI (N = 1,094), where the correlation reaches 0.40. In summary, negative economic events appear to lead firms to jointly record income-decreasing NRTAX and SPI in the same quarter, although it is uncommon (only 1.6% of firm-quarters).

4 Economics or opportunism

We next analyze whether nonrecurring income taxes represent economic events or opportunistic managerial behavior. We test 1) whether NRTAX predicts future earnings, 2) whether NRTAX explains meeting or beating future analyst earnings targets, 3) the relation between NRTAX and restatements, 4) the trend in GAAP quarterly ETRs when the firm has NRTAX, 5) the relation between special items and NRTAX, and 6) market reactions to NRTAX.

4.1 Predictive power of nonrecurring income taxes for future earnings

In Table 6, we examine the predictive power of nonrecurring income taxes for future earnings. Following Doyle et al. (2003) and Curtis et al. (2014), we regress the cumulative four future quarters of operating earnings on current period quarterly earnings, special items, and one-time tax items. The model is as follows:

∑Op. Earningsq+1,q+4 is the sum of future earnings per share from operations (OPEPSQ) from quarter q + 1 to quarter q + 4 scaled by the stock price (Compustat’s OPEPSQ excludes NRTAX and SPI). Op. Earningsq equals the earnings per share from operations in quarter q scaled by price. If operating earnings were perfectly persistent, we would expect the coefficient on Op. Earningsq to equal four. We scale SPI and NRTAX by market value of equity. Following Kolev et al. (2008), we control for firm sales growth, firm size, earnings volatility, reporting negative pretax earnings, and book-to-market ratio. We include industry, year, and fiscal quarter fixed effects and cluster standard errors by firm.

Table 6, Column 1 shows that quarterly NRTAX significantly predicts future earnings, but the economic magnitude (coeff = 0.256) is small. Consistent with prior studies, special items also significantly predict future earnings—and with a larger absolute coefficient (coeff = -0.409) than NRTAX (p-value = 0.05).Footnote 20 Given that researchers generally consider special items to be largely transitory in nature, we conclude that NRTAX is also transitory on average.Footnote 21

In Column 2, we find that only income-decreasing NRTAX predicts future earnings. For managers to opportunistically use income-decreasing NRTAX, managers potentially inflate the NRTAX amount while excluding income-decreasing NRTAX from Street earnings (similar to the treatment of negative special items in McVay (2006)). Managers can also potentially benefit from lower tax expense in future quarters. However, we find that neither past nor future ETRs show abnormal changes downward based on current NRTAX (see also Section 4.4), which is inconsistent with such an argument. Further, note that the NRTAX amount is signed so the positive coefficient on income-decreasing NRTAX predicts decreases in future earnings. Managerial opportunism could also occur if managers issue opaque disclosures about transitory gains (Curtis et al. 2014). However, income-increasing NRTAX does not significantly predict future earnings.

We also examine whether NRTAX predicts Street earnings (columns 3 and 4) and future GAAP tax expense (columns 5 and 6). We find no such evidence. Thus, nonrecurring income taxes appear transitory, similar to special items. The limited predictive power of nonrecurring income taxes for future earnings suggests that managers disclose them to inform analysts and investors about the low persistence of these items, rather than being motivated by opportunism.

In untabulated tests, we investigate the persistence of NRTAX from the specific events that generate them, using data from our hand-collected sample in Table 3.Footnote 22 Repatriations, VA releases and increases, and audit settlements could recur for firms with material stockpiles of unrepatriated foreign earnings (Blouin and Krull 2009), DTAs that are due to jurisdiction-specific tax attributes like NOLs (Graham and Mills 2008; Mills et al. 2003), or ongoing tax authority examinations (Hanlon et al. 2007). Transition effects from tax law changes would also generate nonrecurring income taxes but seem less likely to recur. Nonrecurring income taxes from restructurings or mergers with predictive power for future earnings could indicate managerial opportunism (Bens and Johnston 2010). We expect that the type of nonrecurring income tax with the greatest implications for future earnings would be increases or decreases in VAs, consistent with evidence, in Dhaliwal et al. (2013), that VA increases and decreases signal managers’ private information about future earnings.

We find that VA increases (income-decreasing NRTAX due to lower realizability estimates of DTAs) are associated with lower earnings in the next four quarters (p-value < 0.01). In contrast, we do not find that VA releases are associated with future earnings. Repatriations of foreign earnings, tax law changes, and tax audit settlements do not have significant predictive power for future earnings. Finally, NRTAX from restructurings or mergers or the “other” category is not associated with future earnings, although managers potentially have more discretion over the amount or timing of these categories.

4.2 Meet or beat forecasts

We examine whether firms with nonrecurring income taxes are more likely to beat future analyst earnings targets in the same period and over the next four quarters. This tests whether managers have incentives to opportunistically manage earnings using nonrecurring income taxes. Similarly, managers have incentives to opportunistically disclose special items because special items are positively associated with meeting or beating analyst forecasts (Doyle et al. 2013; Cain et al. 2019). We estimate the following linear regression equation:

MBEq equals 1 if the firm meets or beats the analyst consensus forecast by 0 to 3 cents per share (Cain et al. 2019) and 0 otherwise, and %MBEq+1,q+4 equals the percentage of quarters from quarter q + 1 to q + 4 the firm meets or beats the forecast by 0 to 3 cents per share. We examine small analyst forecasts beats because managers have a strong incentive to manage earnings in these cases. We also examine the next four fiscal quarters because opportunistic use of nonrecurring taxes may increase the firm’s ability to meet forecasts in an undetermined future quarter, similar to special items (Cain et al. 2019). We control for firm size, book-to-market ratio, and quarterly stock returns (Cain et al. 2019) and include industry, year, and fiscal quarter fixed effects and cluster standard errors by firm.

Table 7 shows little evidence of opportunism based on meeting or beating analysts’ forecasts. Columns 1, 2, and 3 examine meet or beat in the same quarter of the NRTAX. In columns 1 and 2, we do not find an association with NRTAX; column 3, however, shows a negative association of MBE with income-increasing NRTAX, which runs counter to the conjecture that firms would try to obscure an income-increasing tax item that would otherwise help the firm beat the forecast. In columns 4–6, we find no association between NRTAX and future %MBE.

4.3 Restatements

If managers opportunistically misclassify or inaccurately estimate nonrecurring income taxes, we expect that they will need to restate GAAP tax expense. We estimate the association between NRTAX and future financial restatements using the following linear probability model:

Restatey+1 is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm files an accounting restatement (Audit Analytics RES_ACCOUNTING = 1) in year y + 1 and 0 otherwise. Tax Restatey+1 is an indicator variable equal to 1 if tax expense is restated (RES_ACC_RES_FKEY_LIST = 18) in year y + 1 and 0 otherwise. We control for firm size, volatility in sales and cash flows, operating cycle length, sales growth, and annual stock returns (Cain et al. 2019). We include industry, year, and fiscal quarter fixed effects and cluster standard errors by firm.

Panel A of Table 8 shows results. Column 1 shows no significant association between financial restatements and NRTAX. However, Column 2 shows that the absolute value of NRTAX is significantly associated with future restatements, which suggests that large, absolute NRTAX amounts lead to future restatements because they are material and difficult to estimate. In column 3, we also find a positive association between the incidence of NRTAX and future financial restatements. In columns 4–6, we do not find evidence that NRTAX is associated with future restatements of GAAP tax expense.

To better understand the results in columns 2 and 3, we separately examine income-increasing and income-decreasing NRTAX in Panels B and C. In Panel B, we find that income-increasing NRTAX is positively associated with future financial restatements. The amount of NRTAX (column 1) explains financial restatements, but the incidence of NRTAX (column 2) does not. Neither the amount nor incidence of NRTAX explains tax-specific restatements in columns 3 or 4. In Panel C, only the incidence of an income-decreasing NRTAX is positively associated with a future restatement (column 2), but the other specifications show no association for income-decreasing NRTAX and restatements.

Overall, the evidence does not support a relation between NRTAX and opportunism. Although NRTAX is related to future restatements in certain specifications, these restatements are unrelated to tax expense. Thus, the findings are consistent with a coincidental relation between NRTAX and non-tax restatements occurring when firm complexity is high, which likely leads to errors in other accounts that result in restatements. However, the underlying issue that results in the presence of NRTAX and the presence of future restatements is not inherently based on the NRTAX issue itself because the restatement does not manifest through a tax account.

4.4 ETR patterns

Next, we examine whether ETR patterns display evidence of tax expense shifting by considering quarterly ETRs from quarter q-2 to q + 2 when an NRTAX occurs in quarter q. If managers opportunistically overestimate their income-decreasing nonrecurring income tax to report lower future tax expense (and thereby boost future earnings), we expect quarterly ETRs to decline after the NRTAX. As a baseline, Fig. 1 shows the impact of NRTAX on quarterly GAAP ETRs that are not adjusted for NRTAX. As expected, ETRs increase (decrease) in the presence of an income-decreasing (income-increasing) NRTAX in quarter q. Similarly, Fig. 2 shows a similar impact on ETR when NRTAX occurs in quarter q and potentially other quarters. These ETR changes show that NRTAX materially impacts firm tax expense and earnings.

Quarterly GAAP ETRs from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with NRTAX only in quarter q. Figure 1 shows the impact of income-decreasing and income-increasing nonrecurring income taxes on the trend of quarterly effective tax rates from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with a nonrecurring income tax occurring only in quarter q. Quarterly effective tax rates equal quarterly GAAP tax expense divided by GAAP pretax earnings minus special items

Quarterly GAAP ETRs from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with NRTAX at quarter q and potentially other quarters. Figure 2 shows the impact of income-decreasing and income-increasing nonrecurring income taxes on the trend of quarterly effective tax rates from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with a nonrecurring income tax occurring in quarter q and potentially in other quarters. Quarterly effective tax rates equal quarterly GAAP tax expense divided by GAAP pretax earnings minus special items

To examine whether ETR patterns display evidence of tax expense shifting, we adjust the ETR in quarter q to exclude NRTAX. Figure 3 shows the impact of both income-decreasing and income-increasing NRTAX on quarterly ETRs if the firm only has an NRTAX in quarter q. We find that after adjusting the ETR for NRTAX in quarter q, the ETR is stable for quarters q-2 to q + 2. This result suggests that managers do not overestimate the amount of income-decreasing nonrecurring income tax to reduce future tax expense. We find a similar stable ETR pattern for income-increasing NRTAX. Overall, the adjusted quarterly ETR data in Fig. 3 displays a relatively stable pattern.

Quarterly GAAP ETRs excluding NRTAX from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with NRTAX only in quarter q. Figure 3 shows the impact of nonrecurring income taxes on the trend of quarterly effective tax rates excluding nonrecurring income taxes from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with a nonrecurring income tax occurring only in quarter q. Quarterly effective tax rates excluding nonrecurring income taxes equal quarterly GAAP tax expense plus nonrecurring income taxes divided by GAAP pretax earnings minus special items

In Fig. 4, we also include observations where NRTAX occurs in quarters other than quarter q (and remove NRTAX from all quarters in which it appears). Again, we see no evidence that managers use NRTAX to boost future earnings as ETRs are similar in the future.

Quarterly GAAP ETRs excluding NRTAX from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with NRTAX at quarter q and potentially other quarters. Figure 4 shows the impact of nonrecurring income taxes on the trend of quarterly effective tax rates excluding nonrecurring income taxes from quarter q-2 to q + 2 with a nonrecurring income tax occurring in quarter q and potentially other quarters. Quarterly effective tax rates excluding nonrecurring income taxes equal quarterly GAAP tax expense plus nonrecurring income taxes divided by GAAP pretax earnings minus special items

4.5 Market reaction

We next examine whether investors react to nonrecurring income taxes. We estimate the following earnings response coefficient (ERC) regression:

CARq equals the cumulative three-day abnormal stock return measured as the stock return around the quarterly earnings release (day −1 to day + 1) minus the cumulative return of a value-weighted portfolio of firms in the same size decile. Earnings Surpriseq equals Street earnings (I/B/E/S actual earnings) minus consensus analyst earnings forecast (I/B/E/S median analyst forecast) scaled by beginning-of-quarter market value of equity. We control for firm size, book-to-market ratio, revenue growth, lagged annual profitability, stock momentum measured as stock returns over the prior six months, and industry fixed effects (Wagner et al. 2018a, 2018b). We estimate heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors. We also analyze the first three quarters separately from the fourth quarter. Managers have greater discretion over nonrecurring income taxes occurring in quarters 1, 2, and 3 because of greater auditor oversight in the fourth quarter (Brown and Pinello 2007), which could impact how investors react.

In Table 9, we find no evidence that investors react to nonrecurring income taxes at the earnings announcement.Footnote 23 We conjecture that this is because they react earlier, as some managers issue guidance for nonrecurring income taxes. In Appendix 3, we present examples of firm pre-announcements for nonrecurring income taxes from tax audit settlements, restructurings, and foreign earnings repatriations. For example, Harris Corporation updated its earnings guidance during its first quarter to reflect a favorable tax audit settlement that increased earnings.

We examine whether investors react during the quarter by replacing the dependent variable (CARq) in Eq. 5 with the quarterly return (Quarter Returnq), which equals the buy-and-hold abnormal stock return measured as the stock return from two days after the earnings release for quarter q-1 to one day before the earnings release for quarter q, minus the buy-and-hold return of a value-weighted portfolio of firms in the same size decile.

In Column 1 of Table 10, we find a significant positive coefficient on NRTAX, suggesting that investors react to NRTAX during the quarter. The results in column 2 suggest that investors only react significantly to income-increasing NRTAX. Columns 3 and 4 show that investors do not generally react to NRTAX during the quarters 1, 2, and 3, but do react to income-increasing NRTAX. Columns 5 and 6 show that investors generally react to NRTAX in the fourth quarter, driven by income-increasing NRTAX.Footnote 24 In one-tailed tests, income-decreasing NRTAX (p = 0.06) is significantly associated with quarterly stock returns in columns 2 and 6. Similarly, in annual return tests (untabulated), we find that stock returns are significantly associated with the NRTAX amount, even when controlling for its individual components (e.g., changes in deferred tax assets), which suggests NRTAX offers information about nonrecurring amounts in earnings incremental to the proxies of its individual components.Footnote 25 Finally, as investors react over the return period rather than at the earnings release, the evidence appears inconsistent with NRTAX reflecting managerial opportunism.

5 Application of NRTAX to research setting – ETR volatility

In this section, we consider a scenario in which researchers may wish to adjust for NRTAX, depending on their research question. Specifically, researchers using measures related to the volatility of ETR measures may or may not want one-time items to be included in such measures, depending on what they are interested in examining. For example, researchers interested in an inclusive measure that includes all events that affect ETRs would want to include NRTAX. However, some researchers may not want to include the essentially random timing of tax settlements in such a measure and should be aware that their inclusion distorts the measure.

Table 11, Panel A shows the frequency of annual NRTAX by the decile of ETR volatility. ETR volatility equals the standard deviation of the annual ETR in the past five years (Guenther et al. 2017).Footnote 26 In the first row, we find that NRTAX occurs in 20% of firm-years in the lowest decile and 17% of firm-years in the highest decile of cash ETR volatility. The frequency of NRTAX does not appear to have a strong relationship with the volatility of cash ETR, because not all NRTAX items have cash effects. Specifically, favorable releases of reserves for audit resolutions, valuation allowance changes, tax law change remeasurements of DTAs and DTLs, and merger remeasurements of tax balances need not have cash effects. However, earnings repatriations and the payment of claims due in audit resolutions, or refunds related to DTAs, could have cash effects in the current period.Footnote 27 After adjusting the cash ETR for NRTAX, NRTAX frequency declines to 17% in the lowest decile of cash ETR volatility and increases to 20% in the highest decile of cash ETR volatility, and the deciles in between the lowest and highest all have NRTAX frequency between 19 and 21%.

In contrast to the cash ETR, the frequency of NRTAX generally increases as the volatility of GAAP ETR increases, consistent with the NRTAX having an ETR effect even when it does not affect cash flows. Although not a monotonic increase, the frequency of firms reporting NRTAX is markedly different based on GAAP ETR volatility decile, increasing from 6.9% in the first decile to 23% in the last decile. Adjusting GAAP ETR for NRTAX shows 11% NRTAX in the first decile and 17% NRTAX in the last decile of GAAP ETR volatility. Thus, adjusting GAAP ETRs for NRTAX appears to distribute the NRTAX more evenly and mitigate the impact of NRTAX on GAAP ETR volatility. However, it is likely that firms with more volatile ETR are also more likely to report NRTAX events, so controlling for such events does not completely eliminate the GAAP ETR volatility differences.

We also examine whether adjusting 1-year GAAP ETRs to exclude NRTAX improves their representativeness of long-run tax avoidance. Specifically, we examine whether excluding NRTAX from 1-year GAAP ETRs increases the correlation coefficient with 5-year cash ETRs (Dyreng et al. 2008). In Panel B, we find that the correlation between 5-year cash ETRs and 1-year GAAP ETRs significantly increases from 0.23 to 0.26 after adjusting GAAP ETRs for NRTAX. In addition, the increase in correlation is concentrated in larger firms where NRTAX is most common (see Table 1, Panel D). In the 9th size decile, we find that the correlation coefficient increases from 0.35 to 0.42, and in the 10th size decile we find an increase from 0.39 to 0.47. Overall, these results suggest that NRTAX adds noise to using 1-year GAAP ETRs as a measure for tax avoidance and that adjusting for NRTAX improves the representativeness of GAAP ETRs for tax avoidance.

6 Supplemental tests of tax disruption: the case of TCJA 2017

In Appendix 4, we examine whether financial statement tax information predicts the amount of nonrecurring income taxes from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA). This question is interesting because TCJA is the largest tax reform in 30 years, and its short legislative process prevented most managers from issuing nonrecurring income tax estimates. The legislative process lasted a mere 50 days, starting with its introduction in the House of Representatives on November 2, 2017, and ending with the President’s signature on December 22, 2017. In our main tests, we found that although financial statement tax information provides some explanatory power, nonrecurring income tax items are generally difficult to predict. In contrast, most firms will record nonrecurring income taxes for a major tax law change like TCJA. However, for large multinational U.S. corporations, it might be difficult to estimate TCJA’s nonrecurring income tax amount from financial statement tax information.

We examine two of TCJA’s changes that generate nonrecurring income tax items in the fourth quarter of 2017. First, TCJA reduced the U.S. corporate tax rate from a top rate of 35% to 21%. Firms recorded nonrecurring income taxes for the re-measurement of deferred tax assets and liabilities at the lower rate. Second, TCJA changes taxation of foreign income earned by U.S. corporations from a worldwide to a territorial system, where the U.S. only taxes earnings sourced in the U.S. As part of the transition, TCJA imposes a one-time mandatory deemed repatriation tax on previously untaxed foreign earnings. Before considering offsetting foreign tax credits, TCJA taxes foreign earnings at 8% if they are invested in non-cash assets and at 15.5% if they are held in cash. Calculating the exact amount of nonrecurring income tax from these two changes could be difficult. Deferred tax assets and liabilities aggregate tax positions from the U.S., states, and foreign countries. Also, some firms’ disclosures for permanently reinvested earnings do not appear to comply with U.S. GAAP (Ayers et al. 2015).

We use a sample of 2,635 U.S. corporations in the fourth quarter of 2017. As expected, most firms report a nonrecurring income tax, and the amounts substantially impacted earnings. Table 13 shows that 77% of U.S. corporations have an NRTAX, and the average benefit is 10 cents per share.Footnote 28 In Table 14, we find that deferred tax assets, deferred tax liabilities, and permanently reinvested earnings significantly explain TCJA’s NRTAX amount. In column 1, we examine all U.S. corporations and find statistically significant coefficients on all variables. The model explains 44% of the variation in NRTAX. In column 2, we restrict the sample to only S&P 500 U.S. corporations, and the model’s explanatory power increases to 54%. Overall, financial statement tax information is more useful in explaining the amount of nonrecurring taxes from TCJA, which contrasts with our main findings that financial statement tax information provides limited explanatory power for nonrecurring income taxes not from major tax reform.

7 Conclusion

While prior studies suggest that nonrecurring income taxes are associated with opportunistic managerial behavior, no study focuses on nonrecurring income taxes, and many studies examining transitory items disregard nonrecurring income taxes. We fill this void by providing the first comprehensive analysis of nonrecurring income taxes. Using Compustat’s NRTAX to proxy for nonrecurring income taxes, we show the relevance of nonrecurring income taxes to financial reporting. NRTAX occurs in about 6% of firm-quarters, with the frequency rising to over 10% for the largest firms. Firms in all industries record NRTAX, and the amounts can materially affect earnings. We find that NRTAX is most commonly recorded for tax audit resolutions, valuation allowance adjustments, tax law changes, and restructurings.

Our tests suggest that nonrecurring taxes are primarily related to economic events. We do not find evidence that nonrecurring income taxes are used to manage current or future quarterly earnings. We also do not find that nonrecurring taxes are associated with future restatements of GAAP tax expense. In addition, after excluding nonrecurring taxes, we find quarterly ETRs are relatively stable. Nonrecurring income taxes have little predictive power for future earnings, and we do not find that they predict future tax expense. Although we find that changes in deferred tax assets and liabilities and the level of permanently reinvested earnings help explain some nonrecurring income taxes, we conclude that it is generally difficult to explain or predict the incidence and amount of nonrecurring income taxes. When we examine stock returns to nonrecurring income taxes, we find that investor reactions to nonrecurring income taxes occur over the quarter they are recorded rather than at the earnings announcement, suggesting that managers generally pre-announce the nonrecurring income tax. Thus, while all earnings items likely contain some managerial opportunism, our findings suggest that nonrecurring income taxes primarily reflect economic events.

Notes

Even for country-level events such as tax law changes, outsiders frequently need guidance from management to understand firm-level effects (Plumlee 2003).

APB 28 itself does not mention discrete items. Rather, the qualifications and dissenting opinions recommend accounting for each interim period as a discrete period. See comments by Messrs Norr, Halvorson, Hayes, and Watt.

Section 30-7 specifies that the estimated annual ETR applied to ordinary income or loss shall exclude “tax related to significant unusual or infrequently occurring items that will be separately reported.” Thus, firms often separately disclose the tax effect of special items because the tax effect on unusual or infrequently occurring items is not part of the estimated annual ETR. However, the tax effect of special items is not included in nonrecurring income taxes.

Compustat began collecting NRTAX in 2001, but the variable is not well-populated until 2005, when many firms disclosed repatriation taxes due to the American Jobs Creation Act of 2005.

In an early version of this study, we randomly selected 400 firms with nonzero NRTAX between 2005 and 2012 and hand-collected the reasons these firms had NRTAX for all firm-quarters between 2005 and 2012. In this version, we expanded our hand-collection of NRTAX reasons to 2005–2017 Q3 for the original 400 firms.

Appendix 2 provides examples of firm disclosures of valuation allowance releases.

For about 30% of quarterly observations, we cannot determine the dollar amounts related to specific issues. Special items are similarly difficult to classify. Johnson et al. (2011) find that 25% of special items from 2001 to 2009 are classified in Compustat’s “other” subcategory.

We follow Cain et al. (2019) and adjust annual variables to quarterly when data are available. Returnsq-1,q equals the stock returns from the end of quarter q-1 to quarter q, and Returnsq-4,q-1 equals the stock returns from the end of quarter q-4 to quarter q-1. ΔBTMq-4,q equals the change in book-to-market ratio. ΔROAq-4,q equals the change in return on assets. Mergery-1 equals 1 if the firm has M&A activity (positive AQS) in year y-1 or y-2, and 0 otherwise. EmployeeDecy-1 equals 1 if the number of employees (EMP) declines from year y-2 to y-1, and 0 otherwise. DiscOpy-1 equals 1 if the firm has discontinued operations (DO), and 0 otherwise. LargeSalesDecq-4,q equals 1 if the firm is in the bottom quintile of sales growth from quarter q-4 to quarter q of its industry-year, and 0 otherwise. ΔSaleq-4,q equals the percent change in sales from quarter q-4 to quarter q. Lossq equals 1 if pretax earnings are less than zero, and 0 otherwise. PctLossq-8,q-1 equals the number of quarters with negative pretax earnings from quarter q-8 to quarter q-1 divided by eight. ΔCFOy-2,y-1 equals the change in cash flows from operations (OANCF minus XIDOC, scaled by net sales). OpCycley-1 equals the operating cycle in year y-1 calculated as the log-transformed sum of days inventory outstanding and receivables outstanding. CapitalIntensityy-1 equals property, plant, and equipment (PPENT). IntangibleIntensityy-1 equals intangible assets (INTAN). Ln(Assetsq) equals the log of total assets at the end of the quarter.

In untabulated analysis, we test whether current financial statement data predicts the next quarter’s NRTAX. We find explanatory power from deferred tax assets, PRE, tax loss carryforwards, pretax losses, employee declines, capital intensity, and intangible intensity for future NRTAX. We no longer find an association between quarterly ETR changes and future NRTAX, so ETR changes do not appear useful in predicting future NRTAX. The explanatory power for the future NRTAX amount is poor relative to its power for the contemporaneous NRTAX amount, although many variables remain significant. Historical financial information weakly predicts the amount of future nonrecurring income taxes. In contrast to the explanatory power that reached 18% for explaining the current quarterly amount of NRTAX, the explanatory power is only 1.1% for explaining the next quarter’s NRTAX amount.

For each cross-validation fold, the sample is randomly split into ten equal-sized subsamples with nine subsamples pooled to train the model and one subsample used as a holdout sample to evaluate the model’s performance. Thus, the model’s performance is evaluated ten times for each fold, as each of the ten subsamples serves as a holdout subsample. Sampling the fold ten times gives 100 cross-validation runs.

We calculate each cross-validation run’s AUC by computing the area under the ROC curve with the TPR and FPR for each cutoff percentile from 50 to 100% incremented by 1%.

We test the null hypothesis that the average AUC equals 0.50, which is the AUC of a random classification scheme with corrected resampled t-statistics following Larcker and Zakolyukina (2012).

We present performance at these cutoffs because the annual NRTAX frequency ranges between 4 and 8% (Panel B, Table 1) and quarterly NRTAX frequency ranges between 3 and 13% (untabulated).

For comparison, we examine the validity of the SPI incidence model. As special items are more frequent (55% of firm-quarters have SPI), we randomly select half of the sample to train the SPI incidence model, and examine model performance on the holdout sample. Using a logistic regression, we classify firm-quarters with a likelihood value greater than 0.5 as having SPI. The AUC is 0.73, the TPR is 74%, the FPR is 40%, precision is 69%, and accuracy is 67%. At cutoff likelihood value 0.7, the TPR is 38%, the FPR is 12%, precision is 79%, and accuracy is 60%. These values reflect that the SPI model also has difficulty identifying special items.

In the 24 firm-quarters we found to have NRTAX items, we found seven valuation allowance changes, six tax audit resolutions, two foreign earning repatriations, three restructuring-related tax items, two accounting-related tax items, three unspecified discrete items, and one firm-quarter with a tax audit resolution and valuation allowance change.

Of the 43 firm-quarters for which we could identify why Compustat recorded NRTAX items, we found 12 tax audit resolutions, eight valuation allowance changes, seven repatriations, five deferred tax audit write-offs, four unspecified discrete items, three tax law changes, two tax authority rulings, one restructuring, and one firm with a tax audit resolution and valuation allowance change.

For SPI, we also examine 25 firm-quarters from both situations when the model and Compustat disagree on the existence of quarterly SPI (for comparison). We cannot identify an event or reason why Compustat records an SPI for five of the 25 firm-quarters when our model does not identify an SPI. When Compustat does not record an SPI but the model identifies one, we find that 12 of the 25 firm-quarters have what appear to be special items (e.g., settlements or restructuring charges). Overall, Compustat’s SPI collection is very similar to Compustat’s NRTAX collection.

In the annual NRTAX model, columns 2 and 4 exclude the annual loss indicator because changes in annual ETRs and cash ETRs are set to missing for annual loss firm-years. The quarterly NRTAX model in Panel A includes the quarterly pretax loss indicator, as the ETR denominator is the year-to-date pretax earnings.

We test the magnitude of coefficients on SPI and NRTAX by creating a negative NRTAX variable equal to NRTAX times negative one. Using this variable instead of NRTAX in Eq. 2, we test the equality of coefficients for SPI and NRTAX.

Consistent with Kolev et al. (2008), Curtis et al. (2014), Doyle et al. (2003), and Hsu and Kross (2011), we find a negative association between special items and future earnings. However, other studies document a positive association between special items and future earnings (Chen 2010; Gu and Chen 2004; Jones and Smith 2011).

We combine NRTAX from error/method changes, court rulings, and tax refunds with the “other” category because these types have less than 20 observations.

We examine whether the association between stock returns and NRTAX depends on firm information environments as proxied by average quarterly bid-ask spread and residual analyst coverage (Hong, Lim, and Stein 2007), where firms with below (above) median values of bid-ask spread (coverage) are strong information environments. We do not find significant differences in the association between NRTAX and three-day stock returns around the earnings announcement based on the quality of the information environment (untabulated).

We also do not find significant differences in the association between NRTAX and quarterly stock returns based on the information environment quality, except for in quarters 1–3, where firms with above median residual analyst following have a significantly greater association between NRTAX and quarterly stock returns than firms with below median residual analyst following (untabulated).

After adding annual changes in GAAP and cash ETRs as explanatory variables, NRTAX is not significantly associated with annual stock returns. However, these variables reduce the sample size by 30%, as ETRs require positive pretax earnings and, in this reduced sample, NRTAX is not significantly associated with returns even when excluding the ETRs. We conclude that NRTAX adds information for firms with negative pretax earnings.

Cash ETR equals taxes paid divided by pretax income minus special items. Cash ETR adjusted for NRTAX equals taxes paid plus nonrecurring income taxes divided by pretax income minus special items. Although some NRTAX events will not have an immediate impact on cash flows, other NRTAX events potentially do (e.g., tax audit resolutions and earnings repatriations). GAAP ETR equals tax expense divided by pretax income minus special items. GAAP ETR adjusted for NRTAX equals tax expense plus nonrecurring income taxes divided by pretax income minus special items. To calculate a meaningful ETR, we require the numerator and denominator for the ETR to be positive. For comparison, we keep the sample consistent by excluding observations missing data for any ETR calculation.

Repatriations often generate income-decreasing NRTAX and cash outflows. Other identified NRTAX items typically generate income increases and may or may not have cash effects. In untabulated analyses, we adjust cash ETR only for the income-decreasing NRTAX and consider the volatility of cash ETR. Similar to row 2, we observe the lowest frequency of NRTAX in the lowest decile of cash ETR volatility, and the middle deciles have 19–20% frequency. Thus, we conclude that adjusting cash ETR for NRTAX lowers volatility.

We assume NRTAX reported in the TCJA enactment quarter are attributable to TCJA. To validate this, we randomly select 20 U.S. corporations and match NRTAX to the earnings release disclosures about TCJA effects. We obtain 19 out of 20 matches between firm disclosures of TCJA impact on tax expense and Compustat’s NRTAX. For the firm that did not match, Compustat aggregated other nonrecurring income taxes with the effect of TCJA.

References

Audit Analytics. 2018. Long-term trends in non-GAAP disclosures. https://www.auditanalytics.com/blog/long-term-trends-in-non-gaap-disclosures-a-three-year-overview/. Accessed 5 Feb 2019.

Ayers, Benjamin C., Casey M. Schwab, and Steven Utke. 2015. Noncompliance with mandatory disclosure requirements: The magnitude and determinants of undisclosed permanently reinvested earnings. The Accounting Review 90 (1): 59–93.

Bauman, Christine C., Mark P. Bauman, and Robert F. Halsey. 2001. Do firms use the deferred tax asset valuation allowance to manage earnings? Journal of American Taxation Association 23: 27–48.

Bens, Daniel A., and Rick Johnston. 2010. Accounting discretion: Use or abuse? An analysis of restructuring charges surrounding regulator action. Contemporary Accounting Research 26 (3): 673–699.

Black, Dirk E., and Theodore E. Christensen. 2009. U.S. Managers’ use of ‘pro forma’ adjustments to meet strategic earnings targets. Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting 36: 297–326.

Black, Ervin L., Theodore E. Christensen, Paraskevi V. Kiosse, and Thomas D. Steffen. 2017. Has the regulation of non-GAAP disclosures influenced managers’ use of aggressive earnings exclusions? Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting 32: 209–240.

Black, Dirk E., Theodore E. Christensen, Jack T. Ciesielski, and Benjamin C. Whipple. 2018. Non-GAAP reporting: Evidence from academia and current practice. Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting 45: 259–294.

Black, Dirk E., Thoedore E. Christensen, Jack T. Ciesielski, and Benjamin C. Whipple. 2021. Non-GAAP earnings: A consistency and comparability crisis? Contemporary Accounting Research 38 (3): 1712–1747.

Blouin, Jennifer, and Linda Krull. 2009. Bringing it home: A study of the incentives surrounding the repatriation of foreign earnings under the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004. Journal of Accounting Research 47: 1027–1059.

Bratten, Brian, Cristi Gleason, Stephannie A. Larocque, and Lillian F. Mills. 2017. Forecasting taxes: New evidence from analysts. The Accounting Review 92: 1–19.

Brown, Lawrence D., and Arianna S. Pinello. 2007. To what extent does the financial reporting process curb earnings surprise games? Journal of Accounting Research 45 (5): 947–981.

Burgstahler, David, James Jiambalvo, and Terry Shevlin. 2002. Do stock prices fully reflect the implications of special items for future earnings? Journal of Accounting Research 40: 585–612.

Cain, Carol A., Kalin S. Kolev, and Sarah McVay. 2019. Detecting opportunistic special items. Management Science 66 (5): 1783–2290.

Cazier, Richard, Sonja Rego, Xiaoli Tian, and Ryan Wilson. 2015. The impact of increased disclosure requirements and the standardization of accounting practices on earnings management through the reserve for income taxes. Review of Accounting Studies 20: 436–469.

Chen, Chi-Ying. 2010. Do analysts and investors fully understand the persistence of the items excluded from Street earnings? Review of Accounting Studies 15: 32–69.