Abstract

A widespread perception exists that tax havens facilitate corporate opacity. This study provides new evidence on the association between tax havens and the transparency of firm financial reporting using a unique group of firms whose parent companies are incorporated in tax havens but whose headquarters or primary operations—that is, their base—are in nonhaven countries. While most research suggests a negative association between tax havens and transparency, I examine whether this association depends on the firm’s corporate governance environment as well as its capital market incentives. I find that the negative association is limited to firms subject to weak governance in the base country. In contrast, I find, among firms in stronger governance environments, a positive association between tax haven incorporation and transparency, which is most concentrated among firms with greater capital market incentives. My findings suggest that future researchers should use caution when assuming an unambiguous negative association between tax havens and corporate transparency. The study also provides unique evidence that tax planning can motivate higher transparency in certain settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A widespread belief exists that firms’ use of tax havens facilitates corporate opacity. Tax havens have unique regulations that can weaken shareholders’ ability to discipline managers and directors and can provide opportunities for reduced reporting quality or disclosure for tax haven–incorporated companies (Kun 2004; Moon 2018), which may motivate their managers to be less transparent. Many observers, including researchers, policymakers, and the media, have expressed concerns that tax havens let managers misbehave and hide information from financial statement users (e.g., Desai 2005; Morgenthau 2012; Black et al. 2013; Durnev et al. 2016, 2017; Atwood and Lewellen 2019). For example, the U.S. Senate has argued that the unique laws of tax havens can be used to circumvent U.S. securities safeguards, including disclosure requirements (U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations 2006). Many sources also suggest that tax haven–incorporated companies provide financial information that is unreliable or insufficient to portray a firm’s economic situation.

This study examines whether tax haven–incorporated firms exhibit higher or lower financial reporting transparency, compared to other multinational corporations. While research widely suggests that tax havens are associated with less transparency, I examine whether this association varies with the firm’s corporate governance environment as well as its capital market incentives. I use a unique sample of decentered “tax haven firms,” where the parent company is incorporated in a tax haven but the corporate group’s headquarters or primary operations remain in a nonhaven country (i.e., a country that is not a tax haven). Desai (2009) defines the “decentering” of the global firm as the strategic unbundling of its geographic “homes.” Tax haven parent incorporation strategically separates the firm’s tax and legal home (i.e., the incorporation country) from the nonhaven country where the firm is based (i.e., the country of headquarters or primary operations), which I label the “base country” (Atwood and Lewellen 2019).Footnote 1 I define financial reporting transparency (hereafter “transparency”) as “the extent to which the financial reports reveal an entity’s underlying economics in a way that is readily understandable by those using the financial report” (Barth and Schipper 2008, p. 174).Footnote 2 Transparency encompasses both earnings and disclosures.

Examining firms with tax haven parents is important for several reasons. First, in these firms, the entire corporation falls under the umbrella of the tax haven from a legal standpoint; thus, they have the most overarching, direct exposure to the tax haven and provide a strong setting to examine how tax havens affect corporate financial reporting. Second, these firms are economically significant and prevalent; many of them are included in major stock indices like the S&P 500 (e.g., Accenture PLC, Michael Kors, Eaton Corporation, Schlumberger, and Signet Jewelers). In addition, the number of tax haven–parented firms has grown over time, as tax havens have become increasingly attractive legal domiciles (Desai 2009; Desai and Dharmapala 2010; Allen and Morse 2013). Finally, despite calls for research on tax haven–parented firms and corporate inversions (e.g., Hanlon and Heitzman 2010), researchers still know little about the effects of this corporate structure. As multinationals from around the world continue to incorporate their parents in tax havens, financial statement users need to understand the potential tax and nontax effects of this corporate form.

I use OLS regression to compare transparency between tax haven multinationals (i.e., decentered firms with a tax haven parent) and nonhaven multinationals (i.e., those without a tax haven parent) among a sample of firms based primarily in nonhaven countries. My primary empirical measure of transparency is the earnings transparency measure developed by Barth et al. (2013), which uses annual returns–earnings associations to capture investors’ perceptions of the extent to which a firm’s earnings reflect changes in the firm’s economic situation during the year. My study uses a large panel dataset of multinationals based in 18 different nonhaven countries, including approximately 1,000 tax haven firms. I include base country, industry, and year fixed effects and control for tax aggressiveness, international factors such as accounting standards and currency fluctuations, and a host of other variables shown to influence transparency. Consistent with prior research, I find an overall negative association between tax haven incorporation and transparency in the full sample. I then examine whether the strength of governance in the firm’s base country moderates this association. I argue that strong governance in the base country substantially reduces managers’ expected private benefits of expropriation and therefore reduces their incentives to use a tax haven to decrease transparency. My first hypothesis predicts that strong governance in the base country mitigates the negative association between tax haven incorporation and transparency. I find evidence consistent with this prediction.

I then propose that, in stronger governance settings where the capital market benefits of transparency outweigh managers’ expected private benefits from misconduct, tax haven firms have incentives to increase transparency. Thus my second hypothesis predicts a positive association between tax haven incorporation and transparency among firms with strong governance. While strong governance in the base country substantially reduces managers’ expected benefits from misconduct, the tax haven parent structure still weakens shareholders’ ability to bring civil suits against managers and directors (Kun 2004; Moon 2018), which can encourage managerial opportunism. Without transparency, stakeholders may have difficulty assessing whether the firm’s tax haven activities increase or destroy value. For example, numerous observers have criticized Etsy for its lack of transparency regarding tax haven operations (e.g., Drucker and Barinka 2015; Kapner 2015; Kuehner-Hebert 2015). A researcher commenting on the company asked: “If companies are not disclosing, you have to ask why not? Is it to hide things that they’d feel embarrassed about?” (Drucker and Barinka 2015). As this anecdote suggests, tax haven operations may spawn uncertainty among financial statement users about the firm’s motives and activities, which can result in capital market–related costs. Capital market incentives therefore may motivate managers of tax haven firms to provide higher transparency to earn market participants’ trust (e.g., Lang et al. 2003; Siegel 2005). Consistent with this prediction, I find a positive association between tax haven incorporation and transparency among firms based in strong governance countries.

I then examine in cross-sectional tests the effect of capital market incentives on the association between tax haven incorporation and transparency. I find, among firms based in strong governance countries, that the positive association between tax haven incorporation and transparency is strongest for firms with greater capital market incentives. I also find, among firms based in weak governance countries with less severe expected internal governance problems (i.e., lower ownership concentration), that capital market incentives also lead tax haven firms to be more transparent. Overall, my results suggest that the opacity associated with tax havens is concentrated in settings where potential governance problems are severe. In contrast, in settings where those problems are less severe, capital market incentives motivate tax haven firms to opt for greater transparency.

My findings are robust to numerous alternate specifications. First, difference-in-differences tests using corporate inversions demonstrate that firms based in strong governance countries moving their legal domicile to a tax haven exhibit higher transparency and provide longer disclosures after tax haven incorporation. Second, the results are robust to controlling for potential self-selection bias using a two-stage Heckman (1979) model and also using entropy balancing, which provides a quasi-matched sample to achieve covariate balance between tax haven firms and other multinationals (Hainmueller 2012). Third, I find evidence consistent with my hypotheses when using accruals quality and analyst forecast accuracy as additional transparency proxies. Fourth, I find that IFRS adoption does not significantly affect the findings.

My study contributes to the accounting literature in several ways. It provides new evidence on the effects of tax havens on corporate reporting. Research suggests that tax havens are associated with lower transparency (e.g., Black et al. 2013; Kim and Li 2014; Durnev et al. 2016, 2017). However, studies focusing on tax havens commonly attribute their findings to the tax haven without controlling for other factors known to affect transparency, such as tax aggressiveness. My sample provides a powerful setting in which to study the effect of tax havens on firm transparency because a tax haven is likely to affect reporting and disclosure decisions more directly when the haven is a corporate group’s primary legal domicile. Moreover, while many studies generalize findings associated with tax havens to all haven–incorporated firms, my study offers unique evidence that tax havens are primarily associated with lower transparency in firms facing more severe potential corporate governance problems. My study suggests that the use of tax havens may instead provide the positive externality of greater transparency in stronger corporate governance settings. Importantly, my tests control for tax aggressiveness and other important factors known to impact transparency, allowing me to isolate the tax haven effect. My findings indicate that future researchers should use caution when assuming an unambiguous negative association between tax havens and transparency.

My paper also answers calls for further empirical research on the effects of decentered global firms (e.g., Desai 2009) as well as the effects of corporate inversions and the nontax costs of tax avoidance (e.g., Hanlon and Heitzman 2010). Understanding how decentering and tax avoidance strategies affect transparency is paramount because of the importance of transparent financial information for efficient resource allocation and monitoring (Bushman and Smith 2003; Francis et al. 2009). The paper furthers researchers’ understanding of the association between tax avoidance and firm transparency (e.g., Balakrishnan et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2018) in an international setting. It complements prior studies by showing that tax planning can, at times, result in higher corporate transparency.

Finally, the paper contributes to the literature examining the determinants of corporate transparency in an international setting (e.g., Ball et al. 2000; Bushman et al. 2004). A greater understanding of the association between tax havens and corporate transparency should help all financial statement users, including regulatory and tax authorities, better interpret financial statements and disclosures for tax haven firms.

2 Background, related research, and hypotheses

2.1 Background and related research

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Tax Justice Network, and regulators generally identify tax havens as countries with extremely low tax rates, ineffective informational exchange with other countries, and a lack of transparency (OECD 1998; Tax Justice Network 2007; Gravelle 2015). Common tax havens, such as the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Ireland, and Switzerland, are infamous for their zero-percent or extremely low tax rates and unique laws thought to inhibit transparency. Related research suggests that corporate tax avoidance is a primary motive for multinationals to locate the parent corporation in a tax haven (e.g., Seida and Wempe 2004; Markle and Shackelford 2012; Atwood and Lewellen 2019). The corporate tax savings resulting from tax haven incorporation can enhance growth and cash flows, which can benefit investors. In addition, tax haven incorporation can create important individual tax benefits for foreign investors, which can help tax haven–incorporated firms attract foreign capital.Footnote 3

In addition to tax planning opportunities, research suggests other appealing attributes of tax havens. These jurisdictions primarily use the English language and have British legal origins, low levels of corruption, and sophisticated communications infrastructures (Dharmapala and Hines 2009), all of which are conducive to commerce. Moreover, these countries are commonly labeled “offshore financial centers,” due to their abundance of legal, audit, and other financial service firms that are strictly regulated (Worrell and Lowe 2011). Relatedly, Dharmapala and Hines (2009) suggest that tax havens generally score well on measures of governance, although it is not clear whether these governance attributes apply to “offshore” companies due to the ring-fencing regimes (Leikvang 2012).

Yet research also suggests that investors perceive nontrivial risks associated with having a tax haven parent, as evidenced by higher costs of equity capital (Lewellen et al. 2021), lower firm value (Durnev et al. 2016), and negative market reactions to the announcement of inversions to tax havens (Seida and Wempe 2004). Research suggests that tax haven operations are associated with manager malfeasance and lower corporate transparency (e.g., Desai 2005; Black et al. 2013; Durnev et al. 2017; Atwood and Lewellen 2019). It also points to tax havens as a way for managers to circumvent disclosure requirements or withhold or misreport information to investors (e.g., Kim and Li 2014; Durnev et al. 2016; Durnev et al. 2017, Bennedsen and Zeume 2018). In sum, research suggests that tax havens may be associated with a disconnect between a firm’s financial reports and its underlying economics.

Tax havens are infamous for secrecy laws, which provide opportunities for individuals to hide assets and evade taxes (Hanlon et al. 2015; Leikvang 2012). However, the laws of tax havens most relevant for corporations are those that limit shareholders’ ability to bring civil suits against managers and directors and prevent information gathering in tax haven–incorporated firms. Specifically, tax havens commonly have unique regulations that limit minority shareholders’ ability to bring derivative suits (Kun 2004; Moon 2018) or that limit access to corporate records (e.g., Town and Betts 2015). For firms with a tax haven parent, the corporate group’s primary legal domicile is the haven (Desai 2009), and the laws of the haven governing internal affairs of the corporation and civil cases apply to the entire corporate group.Footnote 4 Consequently, shareholders of tax haven–parented firms may find it more difficult to bring civil suits against officers for negligence or breach of fiduciary care or loyalty duties.

While investors and regulators can prosecute tax haven firm managers in the firm’s base country for criminal misconduct, many types of opportunism involve breaches of the officer’s fiduciary duties of care and loyalty, which instead fall under civil liabilities that tax haven incorporation would severely reduce.Footnote 5 Research suggests many self-interested managerial motives that may encourage lower transparency, such as earnings management (e.g., Cassell et al. 2015), boosting compensation (Balsam 1998), hiding poor performance or bad news (Kothari et al. 2009), and investing inefficiently or in pet projects (e.g., Harford et al. 2008; Biddle et al. 2009). Managers may reduce disclosure, use discretion in accounting, or reduce reporting quality to conceal their value-decreasing activities. Thus the unique laws of the tax haven may enable managers of tax haven firms to breach their fiduciary duties without discipline from investors, which may motivate managers to muddy the firm’s financial reports or disclosures to obfuscate opportunism.

Anecdotal evidence also supports increased legal risk and reduced access to corporate records for shareholders of tax haven firms. For example, Robert Morgenthau (a former Manhattan district attorney) proposes that “when companies use secrecy jurisdictions to commit fraud or to evade sanctions, legal remedies may come as cold comfort” (Morgenthau 2012). Similarly, Connecticut State Treasurer Denise Nappier says, “Shareholders’ rights are clearly diminished in significant ways when companies incorporate offshore” (Plitch 2003). In addition, tax haven firms’ disclosures highlight important legal risks associated with their incorporations. For example, Herbalife’s 10-K states, “Holders of our common shares may face difficulties in protecting their interests because we are incorporated under Cayman Islands law.” The company also points out that “shareholders of Cayman Islands exempted companies such as Herbalife have no general rights under Cayman Islands law to inspect corporate records and accounts or to obtain copies of lists of our shareholders.” Other tax haven firms have similar disclosures. Appendix 1 contains excerpts from tax haven firms’ disclosures.

While it may seem obvious that managers should generally be subject to disclosure regulations and securities laws in the listing country, there are reasons why having a tax haven parent may motivate less transparency, despite listing in a country with a strong regulatory environment. Most importantly, having the firm’s parent entity incorporated in a tax haven will reduce shareholders’ ability to bring civil suits against managers or directors as discussed above, regardless of the listing location. Furthermore, special reporting exceptions for foreign issuers (such as in the United States for foreign private issuers and in the United Kingdom for overseas issuers) may reduce disclosure requirements for tax haven–incorporated firms. For example, in the United States, foreign firms face less stringent disclosure requirements, and the SEC permits foreign private issuers to follow “home country” practice in disclosure requirements (Bell 2019). These firms are not required to file current reports of major events (i.e., 8-K) and are exempt from Regulation FD (Nemeth 2017). They are instead subject to the regulations of the tax haven, which are generally minimal for offshore firms. Therefore, managers of tax haven–incorporated firms may be able to engage in important transactions without prompt disclosure or may be able to delay the release of bad news.Footnote 6

Consistent with the theory described above, a plethora of research suggests that tax haven use is associated with lower transparency (e.g., Desai 2005; Desai and Dharmapala 2006; Desai et al. 2007; Dyreng et al. 2012; Black et al. 2013; Durnev et al. 2016; Durnev et al. 2017; Bennedsen and Zeume 2018, among many others). Studies find that tax haven parents are associated with lower firm value (Durnev et al. 2016), higher stock price synchronicity (Kim and Li 2014), and lower financial reporting quality (Durnev et al. 2017). Similarly, a number of studies suggest that tax haven subsidiaries are associated with greater opacity (e.g., Bennedsen and Zeume 2018).

Importantly, some studies attribute the lower transparency associated with tax havens to tax avoidance specifically, while others attribute this association to the opacity of the tax haven. For example, both Balakrishnan et al. (2019) and Chen et al. (2018) find that aggressive tax planning is associated with higher information asymmetry, and they use the presence of a tax haven subsidiary as one of their proxies for tax aggressiveness. Tax haven operations could be associated with lower transparency not because of the tax haven specifically but due to aggressive income shifting. Studies of tax havens often attribute their findings to features of the tax haven without controlling for tax aggressiveness (e.g., Durnev et al. 2017; Kim and Li 2014; Bennedsen and Zeume 2018). Many studies also generalize the findings to all firms with tax haven involvement. However, recent research suggests that the effects of tax havens may vary widely with important country governance characteristics (e.g., Atwood and Lewellen 2019; Lewellen et al. 2021). Therefore the empirical questions remain whether the negative association between tax havens and firm transparency persists after controlling for tax aggressiveness and whether the association varies with the firm’s governance environment.

2.2 Hypotheses

Most research and theory suggests that tax haven firms are less transparent than other multinationals. This assumes an overall negative association between tax havens and transparency. However, anecdotes and recent literature suggest that this negative association may not be ubiquitous. The exposure of illicit activities in the data leaks of the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers have not found evidence of misdeeds in large publicly traded companies (e.g., Francis 2016; Blouin et al. 2017). O’Donovan et al. (2019) examine the valuation effects of leaked documents related to the Panama papers and find that, on average, the associated tax haven activities were value increasing and that the value-decreasing activities were concentrated among firms from weak governance countries.

Moreover, while many cross-country studies generalize the harms of tax haven involvement (e.g., Durnev et al. 2016; Kim and Li 2014; Durnev et al. 2017; Bennedsen and Zeume 2018), recent research suggests that these harms may vary based on the governance environment of the nonhaven base country. Atwood and Lewellen (2019) show that having a tax haven parent facilitates a complementary association between tax avoidance and manager diversion only among firms based in weak governance countries. Similarly, Lewellen et al. (2021) find that the cost of equity capital premium associated with having a tax haven parent is stronger for firms with a weak legal environment in the base country. Collectively, related research suggests that the association between tax haven incorporation and transparency may also depend on the strength of a firm’s corporate governance environment.

Although tax haven firms are legally domiciled in tax havens, these firms continue to have significant exposure to the governance environment of the base country through management and operations. Atwood and Lewellen (2019) propose that strong governance in the base country increases shareholders’ and regulators’ abilities to prosecute managers for misconduct, thereby reducing managers’ expected benefits of using the haven for expropriation.Footnote 7 Opacity often obscures managerial misconduct from financial statement users (e.g., Desai and Dharmapala 2006), and strong governance in the base country may reduce managers’ incentives for opacity. Nonetheless, the reduced civil liabilities afforded by the tax haven parent may motivate managers to behave opportunistically even for firms that are based in strong governance countries. Thus the unique laws of tax havens could motivate managers to withhold information or report earnings that do not convey the firm’s economic situation.

However, managers should weigh the costs and benefits when making decisions regarding misconduct and corporate reporting (e.g., Desai and Dharmapala 2006). When the costs of misreporting and misconduct are high, the capital market consequences of opacity likely outweigh the private benefits of misconduct. Moreover, many tax haven firms also list primarily in their base country; therefore, the audit and reporting requirements they face may help deter managers from misreporting and withholding information.Footnote 8 Given the high costs of misconduct for managers of firms based in strong governance countries, I propose that strong governance in the base country reduces managers’ incentives to obfuscate information. This leads to my first hypothesis, as follows.

-

H1: Strong governance in the base country mitigates the negative association between tax haven incorporation and financial reporting transparency.

Although the vast majority of studies suggest that tax havens are associated with lower transparency, I propose that in some settings tax havens may be associated with higher transparency. Firm transparency is most important when investors demand greater information due to uncertainty (Lang et al. 2012). Balakrishnan et al. (2019) find that tax-aggressive firms provide greater disclosure, presumably to offset some of the information asymmetry that innately accompanies tax avoidance. However, they find little evidence that greater disclosure reduces the transparency problems associated with tax aggressiveness. This may be because, in a U.S. setting, the nontax risks associated with avoidance are not great enough to encourage managers to go to great lengths to increase transparency.

Avoiding taxes through a tax haven parent may present significant nontax risks and uncertainty. Haven–parented firms face scrutiny from the media, activist groups, tax authorities, and politicians (e.g., Plitch 2003; Gelles 2014). For example, Walgreens abandoned its plans to redomicile to Switzerland due to political and reputational risks (Rankin 2014). Additionally, haven parent incorporation may create agency concerns due to reduced civil liabilities for managers and directors, even for firms based in strong governance countries. Without adequate transparency, financial statement users may face difficulty in discerning value-increasing tax avoidance activities from value-decreasing managerial opportunism. For example, Etsy faced questions and criticism regarding the lack of transparency associated with operations in Ireland (Drucker and Barinka 2015).

The nontax risks associated with tax haven incorporation can lead to significant undesirable capital market–related costs (e.g., Lewellen et al. 2021) and could deter potential investors. A secondary motive for incorporating the parent entity in a tax haven (beyond corporate tax incentives) may be to attract greater foreign capital, due to the potential for significant investor-level tax benefits (Desai 2009). Thus managers of tax haven firms may have incentives to increase transparency to mitigate adverse capital market costs and attract and retain investors.

Research suggests that managers increase transparency in settings where uncertainty or agency concerns are high. Jensen and Meckling (1976) propose that, in some situations, a manager will engage in bonding activities to signal that the manager will not take actions that harm the principals. Consistent with this theory, research finds that managers engage in reputational bonding by increasing disclosure and accounting quality when agency concerns are high (e.g., Lang et al. 2003; Siegel 2005). Likewise, Balakrishnan et al. (2019) suggest that firms may increase disclosure in an attempt to mitigate information asymmetry resulting from tax avoidance. These studies suggest that capital market incentives motivate higher transparency in settings where uncertainty and agency concerns are high. Thus the uncertainty and nontax risks of tax haven incorporation may motivate managers of tax haven firms to provide higher transparency to bond with capital market participants.

In sum, theory and related research suggest that, in stronger governance settings where the capital market benefits of transparency outweigh managers’ expected private benefits from expropriation, managers of tax haven firms have bonding incentives to increase transparency. This leads to my second hypothesis, as follows.

-

H2: In stronger governance settings, tax haven firms exhibit higher financial reporting transparency relative to other multinationals.

3 Sample selection and research design

3.1 Sample selection

Table 1 presents details on the sample selection procedure. I obtain data for my study from Atwood and Lewellen (2019), who hand collect data on decentered firms with tax haven parents for firms in the Compustat North America and Compustat Global databases from 1990 through 2013.Footnote 9 Following Atwood and Lewellen (2019), I designate a firm as a “tax haven firm” (HAVEN = 1) if (1) its parent is incorporated in a tax haven in year t, and (2) it is primarily based in a nonhaven country. Atwood and Lewellen (2019) hand collect data for tax haven firms to determine the “base” country, which is the nonhaven country of the firm’s headquarters or primary operations.Footnote 10 I drop tax haven firms where the base country cannot be determined. Since I focus on decentered tax haven firms, I also drop firms primarily based in a tax haven. I limit the control sample (i.e., firms without tax haven parents) to multinational corporations, because the operations and tax avoidance strategies of domestic-only firms likely are not comparable to those of tax haven firms, which are multinational by construction.Footnote 11 This research design allows me to examine the differential effects of having a tax haven–incorporated parent company among a sample of multinationals based in nonhaven countries. Since my focus is on the incorporation location of the top-level parent, I retain only the consolidated parent observation and drop observations that are subsidiaries of other corporations (not the top-level parent).Footnote 12

I also drop firm-years without exchange rates available for the country-year, very small firms (firm-years with total assets or total sales less than $1 million), and firms that are not publicly traded. Because base countries without any tax haven firms or with only tax haven firms could differ fundamentally from other countries, I drop countries without both types of firms. After these data cuts, the preliminary sample includes 12,367 tax haven firm-years from 33 base countries. Finally, I drop firm-years without all the variables needed to estimate the primary regression model and countries within this sample without both tax haven and nonhaven firm-years, resulting in a final sample 62,833 firm-years from 18 base countries, including 4,513 tax haven firm-years. This sample includes 999 unique tax haven firms. Of these firms, 25 are “inversion” firms, defined as having at least two years of data both pre and post tax haven incorporation, and the remaining 974 firms appear to have begun as publicly traded firms after incorporating the parent in a tax haven.Footnote 13

Table 2, Panel A, presents the concentration of observations by base country and tax haven country. The average percentage of tax haven–incorporated firms in a base country is 7.2%. In several base countries (e.g., Argentina, China, and Greece), more than 20% of the firms that are based in the country are incorporated in a tax haven.Footnote 14 Ninety-one percent of tax haven firms are incorporated in “dot” havens (Desai et al. 2006). Table 2, Panel B, presents a matrix of observations by tax haven and base country. The “dot” havens are much more prevalent than the “big” havens in most base countries. Consistent with this overall trend, Chinese firms, which comprise a substantial portion of the tax haven sample, are concentrated in Bermuda and the Cayman Islands. However, Malaysian and Indonesian firms seem to prefer Singapore, and Switzerland appears to be the tax haven of choice for Israeli firms. Table 2, Panel C, presents tax haven firm-years by industry and year. The number of tax haven observations has increased over time and is spread fairly evenly across industries.

3.2 Research design

Corporate transparency can be measured in many ways, including corporate reporting quality, the extent of private information acquisition, and information dissemination (Bushman and Smith 2003). Politicians, regulators, researchers, and other interested parties propose that tax havens enable corporations to misreport or obfuscate financial information, suggesting that the association between havens and transparency relates most closely to the corporate reporting facet of transparency. Attacks against tax havens that relate to corporate transparency point to these jurisdictions as vehicles for managers to misreport or hide information from financial statement users, which would result in financial statements that are unreliable or that contain insufficient information to explain the firm’s economic situation. For these reasons, I am interested in the extent to which a firm’s financial statements convey its economic situation, the reliability of its earnings, and whether the firm is withholding or forthcoming with important information. Variation in these transparency attributes can be due to purposeful misstatements or lack of adequate disclosure, or greater earnings quality and disclosure.

I implicitly assume a baseline negative association between tax haven incorporation and transparency in the overall sample based on inferences from prior research. I begin by estimating the following equation using a pooled sample of all firm-years.

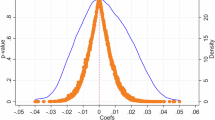

HAVEN is the variable of interest (as previously defined). A negative coefficient on HAVEN (γ1) indicates that, on average, tax haven firms exhibit lower transparency, compared to other multinationals. My primary transparency proxy (TRANS) is the contemporaneous association between earnings and annual returns based on the earnings transparency measure developed by Barth et al. (2013).Footnote 15 I use the returns–earnings association as my primary transparency proxy for several reasons. First, this measure specifically relates to corporate reporting, which is the transparency facet I focus on in this study. Second, it assumes that stock returns reflect changes in the firm’s underlying economics, and measures investors’ perceptions of the extent to which the financial reports represent the company’s underlying economics, which relates closely to my transparency definition. The measure also provides evidence on the reliability of earnings and managers’ forthcomingness with information. A lower covariance between returns and earnings captures investors’ uncertainty about whether earnings convey a firm’s underlying economics, which can be caused by earnings that are unreliable (due to earnings management, misstatements, etc.) or financial reports that do not contain enough information to be readily understandable (due to opacity or lack of disclosure). In addition, by using annual return windows, this measure encompasses all information provided throughout the year that helps investors understand how the firm’s earnings convey the firm’s economic situation, including earnings and other disclosures. Finally, this measure is computable for a wide range of firms.Footnote 16

Because returns–earnings associations can vary considerably in an international setting, I take several steps to provide assurance that variation in financial reporting across countries does not drive the results. Barth et al. (2013) develop industry-year portfolios to estimate the firm’s differential returns–earnings association. I modify the Barth et al. (2013) measure for use in an international sample and estimate the returns–earnings association by accounting standard-industry-year portfolio.Footnote 17 Thus, the coefficient on TRANS reflects the firm’s differential returns–earnings association, compared to firms in the same year and industry using the same accounting standard. I also include fixed effects for the firm’s base country to control for other unobservable factors that may vary by country. Finally, I include several control variables, including an indicator variable for dual listings on more than one stock exchange (DUAL) and exchange rate volatility (EXRATEVOL). I also include an indicator variable equal to 1 for firms using U.S. GAAP (USGAAP), since research shows that value relevance is higher for firms using U.S. GAAP, compared to those using IFRS (Barth et al. 2012).Footnote 18

I include control variables in Eq. (1) from literature examining determinants of long-run returns–earnings associations (e.g., Collins and Kothari 1989; Hayn 1995; Warfield et al. 1995; Billings 1999) and earnings quality (e.g., Francis et al. 2005a; Doyle et al. 2007). I include firm size (SIZE), growth (GROWTH), earnings volatility (EARNVOL), leverage (DEBT), negative earnings (LOSS), operating cycle (OPCYCLE), and firm age (AGE). I expect a positive (negative) association between TRANS and SIZE and AGE (GROWTH, EARNVOL, DEBT, OPCYCLE, and LOSS). Since the literature documents an association between tax aggressiveness and information asymmetry (e.g., Balakrishnan et al. 2019), I include a control for tax aggressiveness (TAXAGG) to ensure that the effect of the tax haven is distinct from that of tax aggressiveness. I expect a negative coefficient on TAXAGG.

I also include other variables to control for tax planning and complexity, including an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm has tax haven subsidiaries (HAVENSUB), the number of countries in which the firm operates (NCO), and the number of subsidiaries (NSUB).Footnote 19 The literature suggests a negative association between tax haven subsidiaries and transparency; however, tax aggressiveness and complexity may drive this association. Thus I expect a negative or insignificant coefficient on HAVENSUB. Although I generally expect complexity to be associated with lower transparency, NCO and NSUB may also reflect firm size, so I have no specific prediction on the signs of the coefficients on these variables. In all models, I include fixed effects for the base country, industry, and year, and I cluster standard errors by firm (Petersen 2009).

My first hypothesis proposes that strong governance in the base country mitigates the overall negative association between the tax haven incorporation and transparency. To test this hypothesis, I expand Eq. (1) as follows.

I use the investor protection score (Investor Protection) from Atwood and Lewellen (2019) to measure the strength of governance in the base country. Investor Protection is the average of four World Bank indices (Extent of Director Liability, Ease of Shareholder Suits, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption), which are scaled to range between 1 and 10 for comparability. Because the indices are not available for every year and are very stable within countries, Atwood and Lewellen (2019) average them by country using the years in their sample for which data are available (1996–2013 for Rule of Law and Control of Corruption and 2004–2013 for Director Liability and Ease of Shareholder Suits). Thus Investor Protection is a time-invariant measure of the average level of investor protections in each country during the sample period. Strong is an indicator variable equal to 1 if Investor Protection in the firm’s base country is greater than the mean of the sample countries of 6.45 and 0 otherwise. The base country fixed effects capture the main effect of Strong. A positive coefficient on HAVEN*Strong in Eq. (2) indicates that strong governance in the base country mitigates the negative association between tax haven incorporation and earnings transparency.Footnote 20,Footnote 21

To test H2, which proposes that, in stronger governance settings, tax haven firms are more transparent than other firms, I estimate Eq. (1) using only the subsample of firms based in strong governance countries (Strong = 1). A positive coefficient on HAVEN indicates that tax haven firms are more transparent, compared to other firms facing similar strength of governance in the base country. For comparison, I also estimate Eq. (1) using only the sample of firms with weak governance in the base country (Strong = 0).

4 Primary empirical results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 2, Panel A, presents Investor Protection by base country. Canada and the United States (China and Indonesia) exhibit the strongest (weakest) Investor Protection. Table 3 presents descriptive statistics and univariate comparisons between tax haven firms and other multinationals for the regression variables. In univariate tests, consistent with the predominant perception, tax haven firms exhibit lower earnings transparency (TRANS), compared to other multinationals (p < 0.01). I also find that tax haven firms have lower tax burdens, compared to peers (higher TAXAGG).

4.2 Multivariate results

Table 4, column 1, presents the baseline association between tax haven incorporation and transparency in the full sample using Eq. (1). Consistent with most research and the predominant perception of tax havens, the results in column 1 indicate that tax haven firms exhibit lower earnings transparency, compared to other multinationals (γ1 = −0.016, p < 0.01). Column 2 of Table 4 presents multivariate tests of H1 using Eq. (2). I find a negative coefficient on HAVEN (β1 = −0.029, p < 0.01) and a positive coefficient on HAVEN*Strong (β2 = 0.053, p < 0.01), suggesting that strong governance mitigates the negative association between tax haven incorporation and transparency, which is consistent with H1.

Column 3 presents the results of H2 using Eq. (1) among the subsample of firms based in strong governance countries. In sharp contrast to column 1, I find a significantly positive coefficient on HAVEN in column 3 (γ1 = 0.024, p < 0.01), indicating that tax haven firms exhibit higher earnings transparency, compared to other multinationals based in strong governance countries, which is consistent with H2.Footnote 22 In terms of economic significance, results in column 3 suggest that tax haven firms exhibit 5.29% higher transparency, compared to other multinationals based in strong governance countries.Footnote 23 For comparison, column 4 presents results from Eq. (1) among firms based in weak governance countries. As expected, I find a significantly negative coefficient on HAVEN in column 4 (γ1 = −0.022, p < 0.01).

Control variables in Table 4 are consistent with expectations. I find that the coefficient on TAXAGG is negative and significant across all columns, consistent with the results of Balakrishnan et al. (2019). I also find a negative coefficient on HAVENSUB, although the coefficient is only significant in the weak base country subsample. This finding suggests that tax haven subsidiaries might not be significantly associated with lower transparency in strong governance environments after controlling for tax aggressiveness.

In sum, the results in Table 4 indicate that the overall negative association between tax havens and transparency suggested by the literature is limited to settings where managers have greater opportunities for misconduct (e.g., firms based in weak governance countries). In contrast, among firms where the capital market benefits of transparency likely outweigh the more limited expected private benefits of expropriation (e.g., firms based in strong governance countries), managers of tax haven firms provide significantly higher earnings transparency, compared to other multinationals.Footnote 24

5 Additional analyses

5.1 Cross-sectional tests with greater capital market incentives

In H2, I propose that in stronger governance settings, managers of tax haven firms have stronger capital market–related incentives for higher transparency to attract and retain investors. The potential risks associated with tax havens may deter investors and can make raising capital more expensive (e.g., Lewellen et al. 2021). Firms with greater capital market incentives, such as those with greater demands for external capital and greater capital market visibility, may be the most harmed by any capital market–related costs resulting from their tax haven involvement. Thus, managers of tax haven firms with greater capital market incentives have the strongest bonding incentives for higher transparency to mitigate uncertainties related to their tax haven use.

To provide further evidence on this prediction, I examine whether capital market incentives affect the association between tax havens and transparency in Table 5. I measure capital market demands using an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm’s market capitalization translated into U.S. dollars is in the top quintile by year (High Market Cap). I also use two variables to measure capital market visibility. The first proxy is high analyst following (High Afol), because research suggests that analysts play an especially important information-processing role in international settings (Lang et al. 2012). The second proxy is an indicator variable equal to 1 for firms primarily listed on one of the top stock exchanges of the world that are in strong governance countries (Top Exchg).Footnote 25 I modify Eq. (1) by adding each of these variables individually along with its interaction with HAVEN.

Table 5, Panel A, presents results among firms based in strong governance countries. Consistent with my prediction, in all three columns I find that the positive association between tax haven incorporation and transparency is strongest for firms with higher capital market incentives. This analysis provides evidence that in strong governance settings, managers of tax haven firms with greater capital market incentives have the greatest bonding incentives for higher transparency.

While I find an on-average negative association between tax havens and transparency among firms based in weak governance countries, this association may vary based on managers’ expected benefits of expropriation versus the capital market benefits of higher transparency. Internal governance problems may increase the difficulty of disciplining managers and can therefore increase the expected benefits of expropriation. When potential internal governance problems are less severe and capital market incentives are higher, the capital market benefits of higher transparency may outweigh managers’ expected private benefits from expropriation, motivating managers to bond with investors through higher transparency. Therefore, I also examine cross-sectional variation in the tax haven–transparency association among firms based in weak governance countries, dependent upon both expected internal governance problems and capital market incentives.

Following research that finds a positive association between ownership concentration and expected internal governance problems (e.g., Lang et al. 2012), I split the sample of firms based in weak governance countries into those with higher and lower ownership concentration using the independence score from Bureau Van Dijk.Footnote 26 I predict that capital market incentives motivate higher transparency in tax haven firms with less severe expected internal governance problems (i.e., lower ownership concentration). Panel B of Table 5 presents these results among firms based in weak governance countries. As expected, in the lower ownership concentration subsample in columns 1 through 3, I find that the interaction of HAVEN and each capital market incentive proxy is positive and significant, suggesting that capital market incentives motivate managers of tax haven firms with lower expected internal governance problems to exhibit higher transparency. In contrast, in the high ownership concentration sample in columns 3 through 6, I find that the main effect of HAVEN is negative and significant, and I do not find that higher capital market incentives significantly moderate this effect. In sum, this analysis suggests that, among firms based in weak governance countries, capital market incentives motivate tax haven firm managers to exhibit higher transparency when expected internal governance problems are less severe.

5.2 Difference-in-differences analysis using corporate inversions

My sample includes a few firms that undergo a corporate “inversion” that moves their parent country of incorporation to a tax haven during the sample period. In an effort to provide causal evidence on the association between transparency and tax havens, I examine whether these firms experience a change in transparency after incorporating in the tax haven. I modify Eq. (1) by splitting HAVEN into HAVEN inversion, which includes tax haven firms with at least two years before and after the inversion, and HAVEN noninversion (all other tax haven observations). I add the interaction of HAVEN inversion and Post, which is an indicator variable equal to 1 for all years after the inversion (the year fixed effects absorb the main effect of Post). I limit this sample to firms based in strong governance countries. This sample of corporate inversions includes 23 firms and 327 firm-years (130 firm-years post tax haven incorporation).

I present the results in Table 6. I find an insignificant coefficient on HAVEN inversion, suggesting that tax haven firms did not differ from other firms in transparency before the inversion. I find that the coefficient on HAVEN inversion*Post is significantly positive (Coef. = 0.029, p < 0.05), providing evidence that these firms are more transparent after the inversion. I also find that the coefficient on HAVEN noninversion continues to be significantly positive (Coef. = 0.021, p < 0.01), suggesting that the effect is not isolated to firms undergoing an inversion. I evaluate the parallel trends assumption in column 2 by presenting the coefficient on HAVEN inversion separately for the inversion year (year t) and years surrounding the inversion. I do not find significant coefficients on any years before the inversion, providing further evidence that confounding factors do not drive the results.

5.3 Additional transparency proxies

Since transparency is “a multifaceted characteristic which is not directly observable” (Lang and Maffett 2010, p. 17), to triangulate my results, I tabulate three additional proxies for transparency. The first two focus on accruals quality, which most directly measures the reliability of a firm’s earnings. I use the model from Dechow and Dichev (2002), modified by McNichols (2002), to estimate the extent to which accruals map into past, current, and future cash flows, and I expect a stronger mapping for more transparent firms. ABNACC is the absolute value of the residuals from the accruals mapping equation, which the literature uses as a measure of earnings management (e.g., Prawitt et al. 2009). AQ focuses on variation in the mapping of accruals into cash flows (Dechow and Dichev 2002) and is calculated as the firm-specific three-year standard deviation of residuals from the accruals estimation regression, multiplied by −1 so that accruals quality is increasing in the measure.

My third additional transparency proxy is analyst forecast accuracy. Professional analysts are among the most important financial statement users; thus, understanding how they use accounting information is important (Hope 2003). Their forecasting ability increases with the reliability of earnings and with the quality and quantity of firm disclosure (Hope 2003; Behn et al. 2008). I calculate analyst forecast accuracy (ACCURACY) as the absolute value of the difference between the median consensus EPS forecast and actual EPS for year t scaled by the latest available stock price in year t-1 (all from I/B/E/S summary file) multiplied by −1. In addition to the control variables used in the earnings transparency regressions, I add several additional variables common to analyst forecast accuracy regressions (e.g., Behn et al. 2008), including analyst following (AFOL), earnings levels (EARNLEVEL), earnings surprise (SURPRISE), and forecast horizon (HORIZON).

I estimate Eq. (2), replacing TRANS with each of these variables. Since the data requirements to estimate these models are onerous (accruals quality estimation requires several years of data, and analyst data from I/B/E/S are more sparse), for these tests, I use a sample of firm-years from the 18 base countries in the primary sample with data to estimate all control variables and each additional transparency proxy. In other words, I do not require data to estimate TRANS. The accruals quality (analyst forecast accuracy) results are presented in Panel A (Panel B) of Table 7. Similar to my primary findings, the results in Table 7 suggest that tax haven firms based in strong governance countries exhibit higher transparency as evidenced by higher AQ and ACCURACY and lower ABNACC.

5.4 Changes in disclosure

A limitation of the TRANS measure is that it does not provide direct evidence on whether managers are forthcoming with information or the extent to which the financial reports are readily understandable. The quantity of information disclosed is one factor that may help ensure that financial statement users have enough information to understand the firm’s economic situation. Research suggests that firms striving to be more transparent may provide lengthier disclosures, such as tax footnotes and MD&A (e.g., Bozanic et al. 2017; Balakrishnan et al. 2019). I use the sample of inversion firm-years with 10-K filings from SEC EDGAR and examine whether these firms experience a change in disclosure length after incorporating in the tax haven. I drop the inversion year to avoid a mechanical relation between tax haven incorporation and the quantity of disclosure. I can retrieve 10-K filings for 150 firm-years comprising 12 firms (62 firm-years post inversion). I hand collect the tax footnotes and the MD&A from these filings. I replace TRANS in Eq. (1) with the log of the number of words in the tax footnote, the log of the number of words in the MD&A, or the log of the file size of the 10-K.Footnote 27 I tabulate these results in Table 8. I find that the coefficient on HAVEN is positive and significant (p < 0.01) in all three columns, suggesting that following the inversion these firms provide longer disclosure regarding their tax strategies and presumably regarding the corporate strategy in the MD&A.

5.5 Other untabulated tests and sensitivity analyses

A potential concern with empirical research is that some other unmeasured firm factor, such as strong firm governance, drives the results. To address this concern, I re-estimate Eq. (1) adding an additional control variable for firm-level governance (the E-index from Bebchuk et al. 2009). I use a sample of 11,805 U.S.-based firm-years, including 57 tax haven firm-years, with data for the E-index. Despite the small sample, I continue to find a significantly positive coefficient on HAVEN (γ1 = 0.13, p < 0.01, results untabulated), suggesting that strong firm governance is not driving the primary findings. I also estimate Eq. (1) using the sample of firms based in strong governance countries including firm fixed effects and obtain similar results (γ1 = 0.026, p < 0.10, results untabulated). This finding provides further evidence that some unmeasured firm-specific factor is not driving the results.

Relatedly, I perform two additional analyses to address endogeneity. My results may suffer from selection bias, since the choice to incorporate the parent in a tax haven is not random. To address this potential bias, I use a two-step estimation approach (Heckman 1979; Badertscher et al. 2009; McGuire et al. 2014). I first estimate a probit model regressing HAVEN on the control variables from Eq. (2) with base country fixed effects plus an additional exogenous variable, which measures tax incentive to incorporate the parent entity in a tax haven.Footnote 28 I use the coefficient estimates from the probit model to construct an Inverse Mills Ratio, which I include in the second-stage model (Eq. (2)). Using this specification, I continue to find a significantly negative coefficient on HAVEN (β1 = −0.029, p < 0.01) and a significantly positive coefficient on the interaction of HAVEN*Strong (β2 = 0.053, p < 0.01). The coefficient on the Inverse Mills Ratio is not significant. Alternatively, I use entropy balancing (Hainmueller 2012) to achieve covariate balance across the first, second, and third moments of the variable distribution between tax haven and nonhaven observations. The results from Eq. (2) are unchanged using entropy-balanced covariates.

A second potential concern with the interpretation of my results is that they are attributable to the decentering of the firm more generally rather than tax haven incorporation. To address this concern, I re-estimate Eq. (2) adding a dummy variable that equals 1 for nonhaven firm-years where the base country differs from the incorporation or primary listing country (Desai 2009), including 2,157 decentered nonhaven firm-years. I find that the sign of the coefficient on the decentered nonhaven variable is not significant (Coef. = −0.003; p = 0.54), while the sign and significance of the coefficients on HAVEN and HAVEN*Strong are similar to the primary tests, suggesting that tax haven parent incorporation differs from other types of decentering.

Third, I examine the sensitivity of the results to dropping individual countries. A large proportion of tax haven firms based in weak governance countries are concentrated in China; therefore, I estimate Eq. (1) using only non-Chinese firms based in weak governance countries and find that the coefficient on HAVEN is not significant. However, when estimating the additional transparency models from Table 7 on this subsample, the coefficient on HAVEN remains significantly positive (negative) in the ABNACC (AQ) model and is significantly positive in the ACCURACY model. Thus the analyses offer mixed results on whether a negative association between tax havens and transparency persists outside of China. China has the weakest governance of any sample country, and the number of observations from other weak governance countries is small. Importantly, the primary focus of the paper is on settings where the presupposed negative association between tax haven incorporation and transparency may not hold. Thus, results excluding China suggest that lower transparency associated with tax haven incorporation may be limited to firms facing extremely weak governance, which is consistent with the primary inferences from the paper. I also estimate Eq. (2) dropping all other sample countries individually, and the inferences from the primary tests are unchanged.

Fourth, since the focus of this paper is financial reporting transparency, all my transparency proxies are specific to corporate reporting. However, accounting researchers also measure transparency and information asymmetry in ways not specific to financial reporting. I estimate Eq. (2) replacing TRANS with the estimated bid-ask spread calculated following Abdi and Ranaldo (2017). I find that the main effect of HAVEN is positive and significant, and the interaction of HAVEN*Strong is negative and significant, which is consistent with H1. I find that the sum of these two coefficients is statistically positive and significant but economically close to zero, which is inconsistent with H2. This may be because the raw bid-ask spread is a less precise measure of financial reporting transparency.

Fifth, since many studies find improvements in accounting quality and positive capital market effects related to IFRS adoption (e.g., Barth et al. 2008; Barth et al. 2012; Daske et al. 2008) the tax haven effect may be more pronounced in firms adopting IFRS. However, if firms were using accounting standards that are comparable to U.S. GAAP or IFRS or were committed to transparency before switching to IFRS, the change may have no effect. I examine, in an untabulated test, whether IFRS adoption influences the primary results using a sample of firms based and primarily listed in strong governance countries mandatorily adopting IFRS during the sample period.Footnote 29 I estimate Eq. (1) adding an indicator variable equal to 1 for firm-years using IFRS, and I interact this variable with HAVEN. As expected, I find that the coefficients on the IFRS indicator variable and HAVEN are significantly positive. While the sign is negative, I do not find that the coefficient on HAVEN*IFRS is statistically significant, suggesting that the tax haven effect is not more pronounced in firms adopting IFRS.

Finally, in the primary tests, I exclude firms where the nonhaven base country cannot be determined (e.g., a firm both headquartered and incorporated in Bermuda), which allows me to control for the unobservable factors associated with the nonhaven base country. However, firms that are incorporated in small island “dot” havens (Desai et al. 2006) and those whose base country cannot be determined are interesting because they could be the most egregious tax haven firms. In an untabulated analysis, I estimate Eq. (2), adding firms incorporated and headquartered in dot havens with the data to calculate all regression variables and an indicator variable for these dot haven firms (175 firm-years). I remove the base country fixed effects from this model, since they cannot be determined for these firms. I find that the coefficient on the “dot haven firm” variable is positive and is approaching significance (Coef. = 0.018, p = 0.11), suggesting that these dot tax haven firms are no less transparent than other multinationals, which is consistent with the inferences from the primary results.

6 Conclusion

I provide new evidence on the association between tax haven use and financial reporting transparency using a unique sample of “tax haven firms” with tax haven–incorporated parents that are based primarily in a nonhaven country. I examine whether the association between tax haven incorporation and transparency is conditional on the firm’s corporate governance environment and capital market incentives. My results indicate that the association between tax haven incorporation and transparency depends on the strength of governance in the base country (i.e., the nonhaven country of headquarters or primary operations), in conjunction with capital market incentives. While I find an overall negative association between tax haven incorporation and transparency in the full sample, I find that firms facing weak country-level governance in the base country drive the baseline negative association. In contrast, I find that capital market incentives motivate tax haven firms to provide higher transparency, compared to other multinationals, among firms based in strong governance countries and firms based in weak governance countries with less severe potential internal governance problems. My study provides evidence that low transparency associated with tax havens is not ubiquitous, and the findings suggest that future researchers should use caution when assuming an unambiguous negative association between tax havens and transparency.

My study is subject to limitations, and it points to areas for future research. First, although my study suggests that tax haven incorporation benefits financial statement users in some settings in terms of financial reporting transparency, I do not address the overall benefit to firms of having a tax haven parent. Future research can examine other nontax effects of this corporate strategy. Second, I use within-firm tests and self-selection corrections to mitigate concerns that self-selection biases my analyses; however, I cannot rule out the possibility that management’s preferences regarding transparency influence the decision to incorporate in a tax haven. Third, my findings suggest that tax haven firms based in weak governance countries exhibit lower transparency in their financial reports. Future research could examine whether these firms make more restatements and commit more accounting fraud. Fourth, the inferences from my study are limited to the corporate reporting aspect of transparency. Future research could examine the association between tax havens and other facets of transparency, such as information acquisition and dissemination. Finally, my study does not attempt to draw inferences on factors that contribute to or deter firms’ choices to incorporate the parent entity in a tax haven. Future research could examine the determinants of this corporate strategy as well as why firms choose specific tax havens.

Notes

I assume that the base country is exogenous, following prior research (e.g., El Ghoul et al. 2013).

Financial information is “readily understandable” if it conveys enough information to help users in making economic decisions but not so much detail as to cloud the underlying economics (Barth and Schipper 2008).

The direct benefit to shareholders of investing in a tax haven firm is the low or 0 % withholding tax rates, in contrast to withholding tax rates of other countries, which can range to up to 40% for nonresident investors (Dharmapala 2008). Anecdotal evidence also suggests that attracting foreign capital is an additional motivation for tax haven parent incorporation. Both Ingersoll-Rand and Cooper Industries indicated in their registration statements that reincorporating in a tax haven would help them to attract a wider range of investors. See Appendix 1 for excerpts from these firms’ disclosures.

Although criminal cases against corporate officers are often tried at the federal level (i.e., Securities and Exchange Commission vs. Company X), the laws governing internal affairs of the corporation and civil cases against officers are generally determined by the firm’s legal domicile, which is the tax haven country in the case of tax haven firms. For firms incorporated outside the United States, shareholder suits that are brought in the U.S. district court will still apply the governing rules of the foreign jurisdiction of incorporation (Kun 2004; Moon 2018).

While the weaker shareholder protections resulting from incorporating in a tax haven could provide opportunities for misconduct and low transparency for any firm with a presence in a tax haven, this effect should be most salient for firms with parents incorporated in tax havens, because the corporate law applies to the entire multinational corporation rather than only to the activities of one subsidiary.

Tax haven incorporation could result in lower transparency, and the firm could still receive a clean audit as long as managers do not materially misstate earnings. The auditor’s purpose is to provide reasonable assurance that the financial statements are prepared in accordance with GAAP and are not materially misstated. An auditor does not opine on whether managers are investing prudently, advancing the interests of shareholders, or making vague disclosures, especially if disclosures are voluntary.

Atwood and Lewellen (2019) examine the complementarity between tax avoidance and manager diversion in weak governance settings, using tax haven parents as a unique setting that has the opacity necessary to observe this complementarity. They do not examine whether firms with tax haven parents are more or less transparent than other firms, or whether the association between tax haven parents and transparency varies with the strength of governance.

Sixty-eight percent of firms with tax haven parents in my sample have their primary listing in their base country. When the firm is both based and listed in a strong governance country, shareholders and regulators can bring legal actions against managers in that country in cases of criminal misconduct. For foreign issuers based in weak governance countries, a strong reporting environment in the listing country may not deter manager misconduct (e.g., Chen et al. 2016).

The sample period ends in 2013 because the data from Atwood and Lewellen (2019) used for this study is hand-collected through the year 2013. In an untabulated test, I obtain data through 2016 (prior to the vast changes of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017) for my sample and find that inferences from the hypothesis tests are unchanged in the period of 2014–2016.

A tax haven firm’s base country is the nonhaven country first identified using this algorithm: (1) the country where the firm was incorporated prior to incorporating in the tax haven country, (2) the country where the firm is headquartered, (3) the country where the firm generates more than 50% of its revenue or has more than 50% of its assets, or (4) the country of the firm’s primary operating subsidiary (Allen and Morse 2013). Atwood and Lewellen (2019) determine this information by examining reports from Mergent Online, Mergent Webreports Worldscope, and SEC EDGAR.

For the nonhaven firms from Compustat North America, I classify firm-years with nonmissing nonzero foreign tax (TXFO) or foreign pre-tax income (PIFO) as multinational. For nonhaven firms from Compustat Global, I retrieved geographic segment information from Thomson Eikon, and I classify firm-years reporting more than one geographic segment or reporting revenue outside of the base country as multinational.

In addition to the consolidated parent firm (e.g., Microsoft Corporation), Compustat sometimes also includes significant subsidiaries as a separate observation, even if they are consolidated into the operations of the parent firm. See Table 1 for more details on the process for identifying subsidiaries.

I include financial firms (SIC 6,000–6,999) in my sample; however, many accounting studies drop these firms. My sample includes only 73 tax haven firm-years in this SIC group. All results are robust to their exclusion.

The largest number of firms originate from China. A primary reason that a large number of Chinese firms have top entities incorporated in tax havens is that Chinese firms have had especially strong tax incentives to incorporate their parent entity in a tax haven. Prior to 2008, China had preferential tax rules, including tax holidays and preferential tax rates, for companies incorporated outside of China (Li 2006). Moreover, recent research has found that Chinese-based foreign firms have continued to benefit from tax haven incorporation even after a 2008 tax law change ended the preferential tax rules for foreign entities because they responded to this tax change by shifting more income out of China (An and Tan 2014).

Barth and Schipper (2008) describe three types of empirical proxies to measure transparency, including market-, analyst-, and accounting-based measures. The earnings–return relation is a market-based measure. I tabulate results using analyst and accounting-based measures in additional analyses.

Potential measures of information asymmetry more generally, such as liquidity (e.g., bid-ask spread or the number of zero return days) also reflect other factors, such as the number of shares, demand for the firm’s stock, and transaction costs, and do not directly measure transparency related to financial reporting, which is my construct of interest. I tabulate additional financial reporting transparency measures in additional analyses.

I estimate the model by accounting standard, industry (Fama French 17 classification), and year and require at least 10 observations per estimation. I provide the calculation details for TRANS in Appendix 3. Following research using valuation data in international settings (e.g., Francis et al. 2005b; Doidge et al. 2004), I use returns for the primary listing to estimate TRANS.

I use data from Bureau Van Dijk, which are not historical, to calculate HAVENSUB, NCO, and NSUB. I retrieved these data in January 2018, and these variables are constant throughout the sample for each firm.

I focus on governance as the country-level variable of interest (rather than financial reporting rules or information dissemination) because this factor determines whether, on average, investors can discipline managers. Even if financial reporting requirements should lead to higher transparency, managers of firms based in weak governance countries may be able to avoid following these requirements, due to the lack of potential discipline (e.g., Chen et al. 2016).

The Investor Protection score from Atwood and Lewellen (2019) is preferred to other potential measures of country-level governance (e.g., the Anti-Director Index from La Porta et al. 1998, common law indicator variable), because it captures four underlying facets of governance and therefore more comprehensively measures governance. In addition, Investor Protection can be measured for all countries in my sample, and the period of measurement overlaps well with the sample period, in contrast to the La Porta et al. (1998) data, which ends in 1995. Following Atwood and Lewellen (2019), I use the average of the four components rather than a factor score, because the raw values (ranging from 0 to 10) and the mean split of the simple average are more readily interpretable, compared to a factor score. All inferences regarding the hypotheses are robust to designating Strong based on a common law indicator variable or the mean of the factor score of these four components.

To provide additional evidence that cross-country differences do not drive my results, I also estimate Eq. (1) for a sample of firms based and primarily listed in the United States using U.S. GAAP. I find a positive and significant coefficient on TRANS in this subsample (p < 0.01), which is consistent with the primary results.

Mean TRANS in strong governance countries is 0.454 (untabulated).

To provide evidence on whether tax haven firms engage in more accounting fraud, I retrieve data from Audit Analytics, which is available from 1995 for SEC registrants. I find only two tax haven firms in my sample with evidence of accounting fraud (Tyco International Ltd. and Marvel Technology Group Ltd.). The scarcity of fraud cases suggests that they are isolated incidences rather than being indicative of greater fraud on average in tax haven firms, at least among firms based in strong governance countries such as the United States.

Sixty-two (29) percent of all (tax haven) firm-years are classified as Top Exchg equal to 1.

See Table 5 for details on ownership concentration calculation. Forty-three percent of firms based in weak governance countries have high ownership concentration.

I add a variable for time trend (Timetrend), since disclosures may increase over time. I exclude the fixed effects due to the small sample size.

The exogenous tax incentive variable is calculated as the statutory corporate tax rate in the base country less the mean statutory tax rate of the sample countries in year t. I follow the guidance from Lennox et al. (2012) in implementing the Heckman (1979) procedure. I exclude the exogenous variable from the second-stage model. To qualify as an exclusionary variable, the researcher must assume that this variable should have no direct association with the Y variable (i.e., TRANS). An untabulated regression of TRANS on the exclusionary variable and industry, year, and base country fixed effects confirms no significant association between this variable and TRANS.

I require that firms are both based and listed in IFRS-adopting countries to provide assurance that the firm will be subject to these reporting requirements. I limit the sample to countries with strong governance to hold the country-level governance environment constant, since Daske et al. (2008) find capital market benefits of IFRS adoption only in countries with institutional environments that are conducive to transparency.

References

Abdi, F., and A. Ranaldo. (2017). A simple estimation of bid-ask spreads from daily close, high, and low prices. The Review of Financial Studies 30 (12): 4,437–4,480.

Allen, E.J., and S.C. Morse. (2013). Tax-haven incorporation for U.S.-headquartered firms: No exodus yet. National Tax Journal 66 (2): 395–420,279.

An, Z., and C. Tan. 2014. Taxation and income shifting: Empirical evidence from a quasi-experiment in China. Economic Systems 38 (4): 588–596.

Atwood, T.J., and C. Lewellen. (2019). The complementarity between tax avoidance and manager diversion: Evidence from tax haven firms. Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (1): 259–294.

Badertscher, B.A., J.D. Phillips, M. Pincus, and S.O. Rego. (2009). Earnings management strategies and the trade-off between tax benefits and detection risk: To conform or not to conform? The Accounting Review 84 (1): 63–97.

Balakrishnan, K., J.L. Blouin, and W.R. Guay. (2019). Tax aggressiveness and corporate transparency. The Accounting Review 94 (1): 45–69.

Ball, R., S.P. Kothari, and A. Robin. (2000). The effect of international institutional factors on properties of accounting earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29 (1): 1–51.

Balsam, S. (1998). Discretionary accounting choices and CEO compensation. Contemporary Accounting Research 15 (3): 229–252.

Barth, M.E., and K. Schipper. (2008). Financial reporting transparency. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 23 (2): 173–190.

Barth, M.E., W.R. Landsman, and M.H. Lang. (2008). International accounting standards and accounting quality. Journal of Accounting Research 46 (3): 467–498.

Barth, M.E., W.R. Landsman, M. Lang, and C. Williams. (2012). Are IFRS-based and US GAAP-based accounting amounts comparable? Journal of Accounting and Economics 54 (1): 68–93.

Barth, M.E., Y. Konchitchki, and W.R. Landsman. (2013). Cost of capital and earnings transparency. Journal of Accounting and Economics 55 (2–3): 206–224.

Bebchuk, L., A. Cohen, and A. Ferrell. (2009). What matters in corporate governance? The Review of Financial Studies 22 (2): 783–827.

Behn, B.K., J.-H. Choi, and T. Kang. (2008). Audit quality and properties of analyst earnings forecasts. The Accounting Review 83 (2): 327–349.

Bell, J., Esq. (2019). U.S. securities offerings and exchange listing by foreign private issuers. Morrison Foerster. https://media2.mofo.com/documents/fpi-memo.pdf.

Bennedsen, M., and S. Zeume. (2018). Corporate tax havens and transparency. The Review of Financial Studies 31 (4): 1,221–1,264.