Abstract

Using adverse-selection cost as a proxy for information asymmetry, we find evidence that non-GAAP earnings numbers issued by management (pro forma earnings) and analysts (street earnings) improve price discovery. First, information asymmetry before an earnings announcement is positively associated with the probability of a non-GAAP earnings number at the forthcoming earnings announcement. Second, the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry is greater when managers or analysts issue non-GAAP earnings at the earnings announcement and when the magnitude of the non-GAAP earnings adjustment is larger. Our results suggest that earnings adjustments by analysts and managers increase the amount and precision of earnings information and help to narrow information asymmetry between informed and uninformed traders following earnings announcements. Alternatively, the findings may be attributable to characteristics of non-GAAP firms and overall better reporting quality for those firms rather than non-GAAP earnings disclosure per se.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

When announcing earnings, management may choose to disclose supplemental pro forma earnings per share (EPS) numbers that differ from EPS under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). In addition, the Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System (I/B/E/S) frequently issues street EPS numbers that differ from GAAP EPS. These non-GAAP earnings numbers may provide a better representation of sustainable economic performance than GAAP earnings. Alternatively, because non-GAAP earnings are usually larger than GAAP earnings (88 and 77 % for pro forma and street earnings, respectively, in our sample), non-GAAP earnings may represent a bid to boost stock price.

Because scheduled, informative public announcements provide incentives for private information search, informed trading and information asymmetry increase in the days before and decrease in the days after earnings announcements. We exploit this pattern to examine the incremental informativeness of non-GAAP earnings relative to GAAP earnings. Based on an analysis of the level of and change in information asymmetry around earnings announcements, we provide evidence that pro forma and street earnings improve price discovery. These results hold when controlling for the uncertainty in a firm’s information environment, potential endogeneity from self-selection, and other firm-specific factors expected to be associated with information asymmetry, including market value, trade size, and trading volume.

As a proxy for information asymmetry, we use the adverse-selection component of the bid-ask spread for firms traded on the NASDAQ exchange. Market makers on that exchange face an information asymmetry problem when they trade with informed investors. Absent this adverse selection, as in the case of pure liquidity-driven buy and sell orders, all trades would occur at fixed bid and ask prices with no change in the bid-ask midpoint. Informed investors, however, will place an order, buy or sell, only when the order is advantageous in light of their private information. Therefore one would expect an increase in the bid-ask midpoint following an informed buy order and a decrease following an informed sell order. The adverse-selection component of the bid-ask spread is a form of protection for market makers against losses from trades with investors who have superior private information.

Three primary findings hold for pro forma earnings provided by managers and street earnings provided by I/B/E/S. First, information asymmetry in the pre-announcement period is positively associated with the probability of non-GAAP earnings at the quarterly earnings announcement. Second, the reduction in information asymmetry after earnings announcements is significantly more pronounced when analysts or managers issue non-GAAP earnings. Third, restricting the analysis to non-GAAP quarters, we find that the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry is larger when the magnitude of non-GAAP adjustments (i.e., the absolute difference between GAAP earnings and non-GAAP earnings) is larger. Our findings suggest that non-GAAP earnings adjustments improve the precision of earnings information and accelerate price discovery. However, we recognize that our findings may be attributable to characteristics of non-GAAP firms that result in better overall reporting quality for those firms rather than non-GAAP earnings disclosure per se.

Our work contributes directly to the literature assessing how different classes of investors trade on non-GAAP disclosures (Christensen et al. 2014; Elliott 2006; Frederickson and Miller 2004) and especially compliments the work of Allee et al. (2007) and Bhattacharya et al. (2007). Allee et al. (2007) find that abnormal trading by less sophisticated investors in a 3-day earnings-announcement window is higher when managers provide pro forma earnings disclosures at the earnings announcement. Bhattacharya et al. (2007) find that abnormal trading by less informed investors is positively associated with pro forma forecast errors (pro forma EPS minus the I/B/E/S mean forecast). Both studies use intra-day trade-size data to proxy for investor sophistication and conclude that the announcement-window price reaction to pro forma earnings is attributable primarily to trading by less informed investors.

Although not directly comparable to the findings of Allee et al. (2007) and Bhattacharya et al. (2007), our results are consistent with their attribution of announcement-window price reactions to trading by less informed investors in response to pro forma earnings. Unusually high adverse-selection cost in the pre-announcement window, as we find when the probability of non-GAAP reporting is relatively high, is consistent with sophisticated investors trading on private information in the pre-announcement window in anticipation of securing returns in the announcement window. We would expect, then, that trades in the announcement window are initiated, primarily, by less sophisticated traders who lack the resources to engage in private information search in advance of earnings announcements.

In general, we interpret our results in the light of studies relating disclosure quality to information asymmetry. From that perspective, our findings suggest that non-GAAP earnings contribute to, rather than detract from, the quality of a firm’s earnings disclosures. Consistent with the increased trading by informed investors before informative disclosures (McNichols and Trueman 1994; Kim and Verrecchia 1997), we find that information asymmetry is higher in the pre-announcement period when non-GAAP earnings are more probable at the earnings announcements. Likewise, consistent with prior research concluding that better disclosure and better earnings quality result in lower information asymmetry between informed and uniformed investors (Bhattacharya et al. 2012; Healy and Palepu 2001), we find that the reduction in information asymmetry following earnings announcements is more pronounced when non-GAAP earnings supplement GAAP earnings disclosures.

Our findings have important implications for managers. First, prior studies (Doyle et al. 2003; Gu and Chen 2004; Landsman et al. 2007; Chen 2010) show that street earnings adjustments have predictive value for future earnings that differs from the predictive value of other earnings components. In this context, our findings suggest that managers can increase the precision of earnings and reduce information asymmetry through the explicit identification of atypical earnings components. This should, in turn, reduce a firm’s cost of capital (Botosan et al. 2004).

Second, our findings suggest that management’s disclosure of non-GAAP earnings may improve a firm’s reputation for providing credible information, consistent with an association between investors’ expectation of disclosure quality and managers’ threshold level of disclosure (Verrecchia 1983). Thus non-GAAP disclosures may be one way to reduce “information risk,” which managers identify as a primary goal of their voluntary disclosure decisions (Graham et al. 2005).

2 Institutional background and prior research

Managers and major forecast vendors, including I/B/E/S, usually justify non-GAAP earnings as a better representation of sustainable corporate performance than GAAP earnings because non-GAAP earnings omit elements of GAAP earnings that are nonrecurring,Footnote 1 unimportant, or immaterial in predicting a company’s future cash flows. Indeed, pro forma earnings and street earnings often exclude special items found in GAAP earnings (Black and Christensen 2009; Kolev et al. 2008), and earnings response coefficients (ERCs) for forecast errors derived from pro forma and street earnings are significantly larger than ERCs for forecast errors derived from GAAP operating earnings (Bhattacharya et al. 2003). Similarly, Brown and Sivakumar (2003) show that street earnings are more value relevant than GAAP operating earnings.

Another body of literature argues that non-GAAP earnings may support or create unjustifiable stock valuations. Pro forma earnings frequently help firms achieve earnings targets (Black and Christensen 2009; Lougee and Marquardt 2004), and pro forma earnings are more likely after share price declines (Bhattacharya et al. 2004) and when boards of directors are less independent (Frankel and McVay 2011). Strategic timing of earnings announcements is also linked to pro forma disclosures in a way that suggests managerial opportunism (Brown et al. 2012a). Similarly, analysts are more likely to exclude expenses from street earnings for glamour stocks (Baik et al. 2009). Finally, the well-documented finding that ERCs and value relevance are larger for pro forma and street earnings than they are for GAAP earnings (Bhattacharya et al. 2004; Bowen et al. 2005; Bradshaw and Sloan 2002; Brown and Sivakumar 2003; Johnson and Schwartz 2005; Lougee and Marquardt 2004) may reflect investor fixation on non-GAAP earnings rather than their superior informativeness (Abarbanell and Lehavy 2007; Bradshaw and Sloan 2002; Zhang and Zheng 2011).

3 Development of hypotheses

3.1 Information asymmetry

We adopt a market microstructure perspective of information asymmetry, wherein one subset of market participants (informed traders) has private information that is superior to the information of another subset (uninformed traders). Informed traders are not insiders. Instead, they are individuals or institutions who obtain private information through costly search activities and who expect to benefit when their information becomes public. Information asymmetry between informed and uninformed traders exists even in efficient markets (Lev 1988).

3.2 The informativeness of non-GAAP earnings

We predict that non-GAAP earnings are more informative or precise than GAAP earnings with respect to the value of the firm. We attribute the source of this incremental precision to non-GAAP adjustments that identify components of earnings with unusual implications for future earnings compared to other components of GAAP earnings. For example, assume all firms provide disclosures for the amount of R&D costs but only certain firms (or their analysts) exclude R&D costs from non-GAAP earnings. The incremental informativeness of non-GAAP earnings arises from the explicit indication that R&D costs have different valuation implications than other operating expenses for these non-GAAP firms.

Incremental informativeness for non-GAAP firms assumes that their non-GAAP adjustments reliably indicate differential persistence or predictive value. This assumption is consistent with empirical findings. For example, Doyle et al. (2003) show that one dollar in excluded expense predicts 3.328 dollars of negative cash flow over the next 3 years compared to 7.895 dollars predicted by street earnings. Landsman et al. (2007) find that, while non-GAAP adjustments in street earnings are informative for forecasting future abnormal earnings, the forecasting coefficient for those adjustments is significantly smaller in absolute magnitude than the coefficient for other components of street earnings. Gu and Chen (2004) reach a similar conclusion when comparing core earnings and exclusions by analysts. The common thread in these studies is that non-GAAP exclusions have atypical predictive value compared to other components of net income.

In our example, investors may suspect that R&D costs have differential valuation implications compared to other operating expenses for some subset of GAAP firms. However, investors are likely to be more uncertain about the differential predictive value of R&D costs for GAAP firms than for non-GAAP firms that acknowledge explicitly the atypical nature of R&D costs. Although it is common to argue that non-GAAP exclusions have lower persistence than core earnings, we believe that the only requirement for incremental precision of non-GAAP earnings is that excluded items have persistence or predictive value that differs from other components of net income.

3.3 Pre-announcement period hypothesis

McNichols and Trueman (1994) present a model of private information search by informed traders with finite investment horizons. Informed traders establish equity positions based on their private information before a scheduled public disclosure. Similarly, Kim and Verrecchia (1997) provide a model of informed trading with pre-announcement private information in anticipation of a public disclosure. Earnings announcements create value for informed traders because, in an efficient market, stock prices fully impound all publicly available information, including any previously private information revealed through earnings announcements.

The incentive to acquire private information before a public disclosure increases as the precision of the upcoming public disclosure increases because information with higher precision causes more belief revisions and more opportunities to profit from private information search (Kim and Verrecchia 1991). Information asymmetry (i.e., adverse selection associated with informed trading) should increase as the precision of forthcoming information increases. If non-GAAP earnings disclosures increase the precision of earnings with respect to the value of the firm, informed trading should reflect the likelihood that non-GAAP earnings disclosures will occur at the earnings announcement. Thus our first hypothesis (prediction) is:

H1

In the pre-announcement period, information asymmetry will be positively associated with the probability of non-GAAP earnings disclosures at the forthcoming quarterly earnings announcement.

3.4 Post-announcement period hypotheses

Our post-announcement tests compare the changes in information asymmetry (post-announcement less pre-announcement) for GAAP and non-GAAP earnings quarters. The post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry should be more pronounced as public disclosures become more informative. At the limit, a perfect or noiseless signal about the value of a firm would eliminate the information advantage of previously better informed investors, albeit only temporarily. All other things equal, a larger reduction in information asymmetry should occur when disclosures are more informative.

Earnings announcements have three information components: publicly anticipated, private, and undiscoverable. Publicly anticipated information should not impact information asymmetry in the pre- or post-announcement periods because informed and uninformed traders are similarly aware of it. Announcements that reveal informed traders’ private information should narrow the gap between informed and uninformed (Diamond and Verrecchia 1991; Diamond 1985). At the same time, announcements that reveal previously undiscoverable information may stimulate information processing by, and serve as a source of profits for, traders who can better transform that information into knowledge about a firm’s prospects (Kim and Verrecchia 1994), thereby increasing information asymmetry between informed and uninformed traders. However, the precision of that undiscoverable information limits this increase. Holding constant the amount of undiscoverable information, the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry should be more pronounced when previously undiscoverable information is more precise.

In summary, the post-announcement change in information asymmetry depends on the amount and precision of the pre-disclosure private information and the amount and precision of previously undiscoverable earnings information. If non-GAAP adjustments identify components of GAAP income with atypical persistence and if informed traders have (noisy) estimates of those adjustments in advance of earnings announcements, the disclosure of non-GAAP earnings will transform pre-announcement private information into public knowledge. In addition, if non-GAAP earnings improve the precision or transparency of previously undiscoverable earnings information, the post-announcement information processing advantage of informed traders will be diminished. In both cases, the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry should be more pronounced in non-GAAP than GAAP quarters. Our second hypothesis (prediction) is:

H2

The reduction in information asymmetry in the post-announcement period (post-announcement less pre-announcement asymmetry) will be more pronounced in non-GAAP than GAAP quarters.

For our third hypothesis, we view the magnitude of the non-GAAP adjustments as a proxy for the incremental precision of earnings information and predict that the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry will be increasing with the absolute value of the non-GAAP adjustments. For example, if non-GAAP earnings reliably identify earnings components with atypical persistence, then the disclosure of non-GAAP earnings should increase the precision of earnings for valuation purposes and thereby reduce the information-processing advantage of informed traders. Thus our third hypothesis (prediction) is:

H3

For non-GAAP quarters, the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry will be more pronounced as the absolute value of non-GAAP earnings adjustments increases.

4 Empirical proxies and research design

4.1 Non-GAAP and GAAP firm-quarters

For analysts, we classify a firm-quarter as non-GAAP when EPS, as reported by I/B/E/S in its unadjusted EPS file, differs from Compustat EPS before extraordinary items (Bradshaw and Sloan 2002). When I/B/E/S reports on a diluted (basic) earnings per share basis, we compare I/B/E/S unadjusted EPS to Compustat’s epsfxq (epspxq). For managers, we rely on hand-collected data generously provided to us by Ted Christensen and Erv Black. Following those authors, we classify as non-GAAP any quarter in which management discloses a supplemental EPS number that differs from Compustat’s diluted earnings per share (epsfxq). In supplemental tests, we use GAAP operating EPS (oepsxq) as a benchmark when classifying a quarter as GAAP or non-GAAP (separately for analysts and managers).

4.2 Pre- and post-announcement windows

We expect that informed trading and information asymmetry will increase in advance of a scheduled earnings announcement and that any reduction in information asymmetry will occur soon after earnings are announced. For the pre-announcement window 〈−12, −3〉, we use the 10 days beginning 12 trading days before the quarterly earnings announcement day 〈0〉. For the post-announcement window 〈+3, +12〉, we use the 10 days starting 3 days following the earnings announcement. We avoid the 5-day earnings-announcement window because adverse selection is significantly higher in that period than in others (Brooks 1994; Krinsky and Lee 1996; Lee et al. 1993). By excluding the 2 days before and the 2 days after earnings announcements, we reduce noise that would otherwise affect our pre- and post-announcement tests.

4.3 Adverse-selection cost

We use the adverse-selection component of the bid-ask spread as a proxy for the level of information asymmetry. In a pure dealer market, the bid-ask spread is the difference between the bid price at which the market maker is willing to buy and the higher ask price at which the market maker is willing to sell.Footnote 2 The spread compensates the market maker for three cost elements: order processing, inventory holding, and adverse selection. Adverse selection occurs when a market maker trades with better informed traders.

Informed traders execute trades after they acquire firm-specific private information that makes the quoted bid or quoted ask price favorable to them. In such cases, the market maker is at an information disadvantage and is likely to incur a loss from the trade. For example, an informed trader’s buy order might result in a narrowing of the market maker’s realized spread (and profit) if the midpoint between the bid price and the ask price increases after the trade. By observing order flow and order source, a market maker can adjust her quotes to discourage informed trades or to recover potential losses from informed trading. Larger ex ante quoted spreads protect against adverse selection, and quoted spreads increase as the probability of informed trading increases.

We estimate adverse-selection cost for each firm in our sample on a daily basis using the Lin et al. (1995) model. The model provides an estimate (ADV) of adverse-selection cost as a proportion of the effective spread. (See Appendix 1.) Because effective (and quoted) spreads have a negative relationship with trading volume (Demestz 1968; Tinic 1972; Stoll 1978; Lin et al. 1995; Van Ness et al. 2001), dollar adverse-selection cost will vary across firms with differential trading volume even when ADV is constant across firms. Given the differences in effective spreads across firms and time, we define the daily adverse-selection cost (cents per share) as ASC ij = ADV ij × ESPREAD ij × 100, where ESPREAD ij is the average effective spread over all N trades for firm i in day j. Specifically, \( ESPREAD_{ij} = \mathop \sum \limits_{n = 1}^{N} \left( {|PRICE_{nij} - \, MIDPOINT_{nij} | \times 2} \right)/N_{ij} \). For each earnings announcement, the pre- and post-announcement estimates of adverse-selection cost, ASCpre it and ASCpost it, are the average daily adverse-selection costs over their respective 10-day pre- and post-announcement windows for quarter t.

4.4 Pre-announcement cross-sectional OLS model

Our first test of H1 uses the following cross-sectional OLS regression model:

ASCpre it is the pre-announcement adverse-selection cost for firm i in quarter t. ProbNonGAAP it is one of two proxies for the likelihood of non-GAAP earnings (ProbSTREET it and ProbPROFORMA it ). (See Appendix 3 for detailed descriptions of all variables.) Under H1, we expect adverse-selection cost in the pre-announcement period to be positively associated with the likelihood of non-GAAP earnings (β1 > 0). The model used to estimate ProbSTREET it and ProbPROFORMA it is discussed in Sect. 4.5.1. In this section, we discuss our control variables.

The regression model includes the previous quarter’s pre-announcement adverse-selection cost (ASCpre it−1) to control for any systematic differences between GAAP and non-GAAP firms. If systematic differences between the composition of firms in GAAP and non-GAAP quarters influence ASC in quarter t, those differences should similarly affect quarter t − 1. Thus the lagged value of the dependent variable should (partially) control for any differences in firm composition.

Our model controls for the uncertainty in firms’ information environments because the quality and precision of a firm’s information can affect its adverse-selection cost (Bhattacharya et al. 2012), its cost of capital (Botosan et al. 2004), and its trading costs (Sadka and Scherbina 2007). Relying on the Barron et al. (1998) model, we identify two components of the uncertainty in analyst k’s earnings forecast for firm i in quarter t, namely, idiosyncratic uncertainty (D it ) unique to analyst k’s private information set and common uncertainty (C it ) inherent to shared public information about firm i. (See Appendix 2.) The uncertainty in analysts’ forecasts is distinct from, although clearly related to, the uncertainty about the intrinsic value of firm i conditional on investors’ information set. Consistent with Barron et al. (2002) and Botosan et al. (2004), we scale D it and C it by the absolute value of the actual I/B/E/S earnings per share. In our regression models, we use the percentile ranks of scaled absolute values of D and C as control variables. Equation (1) uses the lagged value C it−1 because C it is derived, in part, from actual EPS for quarter t, which is unknown to investors in the pre-announcement window for quarter t. The coefficients for C it−1 and D it are expected to be positive.

To control for the nonlinear increase in adverse-selection cost as prices increases (Mayhew 2002), the model includes lnMIDPOINT it (the log of the average daily bid-ask midpoint over the 10-day pre-announcement window). Because larger firms generally have better information availability, fewer opportunities for private information search, and less information asymmetry (Brown et al. 2009), our model includes the log of market value of equity (lnMV it ). The model includes trading frequency to control for liquidity effects and consequently lower adverse-selection cost for more frequently traded stocks (Lin et al. 1995). The relation between adverse selection and trade size, by contrast, is ambiguous. Although institutional investors are more likely to negotiate large trades inside the spread (Huang and Stoll 1996), larger trades also may indicate an increased likelihood of informed trading. Trade size (lnTradeSize) is the natural log of the average daily volume per trade over the pre-announcement window, and trading frequency (lnTradeFreq) is the natural log of the average daily buy and sell transactions over the same window.

The model controls for the number of analysts following a stock (ANALYSTS it ), because the greater the number of analysts following a firm, the fewer the incentives for other forms of private information search. Our model includes the book-to-market ratio (BTM it ) because firms with higher growth opportunities are more difficult to value, suggesting that low book-to-market firms provide more incentives for private information search by informed traders (Van Ness et al. 2001). We expect adverse-selection cost to be negatively associated with the number of analysts and the book-to-market ratio.

The variable MBECQ it−1 (the number of consecutive quarters that firm i met or exceeded analysts’ median forecasts) provides an ex ante measure of the likelihood thatn firm i will at least meet its earnings forecast for quarter t. Brown et al. (2009) show that the probability of informed trading is negatively associated with MBECQ, suggesting a negative relation between pre-announcement adverse-selection cost and MBECQ it−1. Ng et al. (2009) present evidence that adverse selection is larger for firms reporting a loss. Thus our model controls for expected performance through the indicator variable LOSS it , which equals 1 if analysts’ median EPS forecast is negative and 0 otherwise.

We also include indicator variables for three important regulatory changes occurring during our sample period: decimalization of bid-ask quotes in 2001 (Bacidore 2001), Regulation FD in 2000, and Regulation G in 2003. We expect adverse-selection cost to decrease after decimalization, given that the effective spread is positively associated with changes in tick size (Bacidore 1997; Bessembinder 1997). Regulation FD forbids publicly traded firms from the selective disclosure of material nonpublic information and is intended to eliminate an information advantage previously enjoyed by favored investors. The regulation should reduce information asymmetry (Eleswarapu et al. 2004). Regulation G, requiring management to reconcile pro forma and GAAP earnings, resulted in a reduction in the frequency and magnitude of the non-GAAP adjustments by I/B/E/S (Entwistle et al. 2006; Heflin and Hsu 2008; Marques 2006) and may have reduced opportunities for private information search. Additionally, we control for year fixed-effects. Any regression model using adverse-selection cost or change in adverse–selection cost as a dependent variable includes our three regulatory indicators and year fixed-effect indicators as controls. We use clustered regression to correct standard errors for within-firm correlation of the error terms (Petersen 2009).

4.5 Treatment effect model

As an alternative to the OLS regression model in Eq. (1), we employ treatment effect models with separate selection and outcome equations. Treatment effect models control for nonrandom treatment assignment and potential coefficient bias in the outcome equation.

4.5.1 Treatment effect model: selection

The selection equation is a probit model, estimated separately for the disclosure choices by analysts and managers. The model relies primarily on a subset of the covariates employed by Lougee and Marquardt (2004) and Brown et al. (2012b). The covariates are intended to capture GAAP earnings informativeness, investor-perception management, regulatory changes, and unspecified factors as reflected in industry membership and prior disclosure choices by I/B/E/S. We recognize that analysts’ and managers’ incentives to report non-GAAP earnings are unlikely to be identical. For example, it is not clear why analysts would have an interest in misleading investors about firm performance in the same way as managers (Barth et al. 2012). In addition, analysts are less likely than managers to possess information that would allow them to adjust earnings to improve informativeness in the absence of nonrecurring items. On the other hand, managers may exert a strong influence on analysts’ exclusion decisions, or analysts’ forecasts (GAAP or non-GAAP) may influence managers’ disclosure choices. Based on these considerations and for ease of comparability, we use the same selection model for analysts and managers.Footnote 3

Earnings informativeness. Managers or analysts may disclose non-GAAP earnings if GAAP earnings are relatively uninformative about the value of the firm. Lougee and Marquardt (2004) show that pro forma earnings are more likely when a firm has more intangible assets (INTANGIBLES), more growth options (SALESGROWTH and market-to-book or MTB), more leverage (LEVERAGE), and higher earnings variability (STDDEVROA). Additionally, because special items are mostly nonrecurring, non-GAAP earnings are more likely for firms with special items (SPECITEMS = 1) than for firms without them (SPECITEMS = 0). We also include total assets (lnTA) in our selection model because larger firms are more likely to experience nonrecurring events (Brown et al. 2012b).

Investor-perception management. Managers may report pro forma earnings to influence the investors’ perception (Schrand and Walther 2000; Barth et al. 2012), particularly when GAAP earnings miss one or more important benchmarks. Thus we include an indicator for negative forecast error (negOPFE) (Lougee and Marquardt 2004) and an indicator for GAAP operating loss (OPLOSS) (Brown et al. 2012b) in our selection model.

Regulatory changes. Our selection model also includes an indicator variable to denote quarters ending before or after the effective date of Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) in 2002. Prior studies document a downward shift in the frequency of street and pro forma earnings (Marques 2006; Heflin and Hsu 2008) and a change in investor perception toward pro forma earnings (Black et al. 2012) after SOX.Footnote 4

Other unspecified factors. Our models include covariates that capture the history of analysts’ disclosure selection. We use two separate variables, one that captures the previous consecutive quarters that I/B/E/S reported GAAP EPS (GQ it−1) and another that captures the previous consecutive quarters that I/B/E/S reported street EPS (NQ it−1). We also control for industry membership because the likelihood of pro forma earnings varies across industries (Brown et al. 2012b). Industry membership and the historical sequence of I/B/E/S actual earnings (GAAP or street) are strong indicators of disclosure selection for analysts and managers in our sample, as we show later.

4.5.2 Treatment effect model: outcome

The pre-announcement treatment-effect outcome model is:

For analysts (managers), NonGAAP it equals 1 if I/B/E/S (managers) issued a street (pro forma) EPS number for firm i in quarter t and 0 otherwise. Except for the treatment variable (NonGAAP), the outcome model is identical for analysts and managers. The pre-announcement outcome model uses the same control variables as the OLS Eq. (1), with the addition of the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). IMR reflects unobserved factors that affect the selection and the outcome as inferred from the correlation between the error terms from the selection and outcome equations. The treatment effect model aims to eliminate (or reduce) bias in the estimation of the coefficient on the indicator treatment variable in the outcome equation. Under H1, the coefficient on NonGAAP is expected to be positive, consistent with a positive treatment effect, that is, higher pre-announcement adverse-selection cost for non-GAAP quarters than for GAAP quarters. We use two-step estimation for all treatment effect models. Results are qualitatively the same with maximum likelihood estimation.

4.6 Post-announcement models

We use treatment effect models exclusively to test H2. Our post-announcement and pre-announcement selection models are identical. However, our post-announcement outcome model differs from our pre-announcement outcome model because our second hypothesis predicts differences in post-announcement changes in adverse selection for GAAP and non-GAAP quarters rather than differences in pre-announcement levels of adverse selection. The post-announcement outcome model is:

In Eq. (3), chgASC is the change in the adverse-selection cost; NonGAAP is the previously defined indicator variable; absFEs is the absolute value of the forecast error scaled by end-of-quarter stock price; chglnMIDPOINT is the change in the log of the midpoint; chglnTradeSize is the change in the log of trade size; and chglnTradeFreq is the change in the log of the number of trades. We calculate changes in ASC, midpoint, trade size, and trade frequency as the post-announcement-window level minus the pre-announcement-window level. Thus a positive (negative) value for those change variables indicates an increase (decrease) in the level of the variable in the post-announcement period relative to the pre-announcement period.Footnote 5 H2 predicts that non-GAAP earnings (and the associated non-GAAP earnings adjustments) reduce information asymmetry more than GAAP earnings alone and that, as a result, the reduction in adverse-selection cost will be more pronounced when a manager reports pro forma earnings or I/B/E/S reports street earnings. Thus, under H2, we expect β1 to be less than zero.

The variable chgC it (=C it − C it−1) is the change in the uncertainty of public earnings information as revealed at the earnings announcement for quarter t compared to quarter t − 1. The variable chgD it+1 (=D it+1 − D it ) captures the change in the uncertainty in analysts’ private information following the quarter t earnings announcement, under the assumption that the pre-announcement forecast dispersion for quarter t + 1 best reflects the level of uncertainty in analysts’ private information following the announcement of earnings for quarter t. As chgC it and chgD t+1 increase, we expect the level of and change in post-announcement adverse selection to be larger (i.e., δ2 > 0 and δ3 > 0). LOSS2 is an indicator variable equal to 1 if actual earnings (as reported by analysts or managers, as appropriate) is negative and 0 otherwise. The sign for the loss variable is difficult to predict because of the high correlation between forecasted and actual losses and because ASCpre reflects the forecasted sign of earnings.

Our post-announcement model for H3 is restricted to non-GAAP (street and pro forma) firm-quarters and examines the association between the change in adverse-selection cost and the magnitude of the non-GAAP earnings adjustments made by analysts and managers. Separately for analysts and managers, we estimate the following OLS model:

In Eq. (4), RANKabsEXs is the rank of absEXs, where absEXs is the absolute value of the difference between street (pro forma) EPS and GAAP EPS, scaled by share price, for analysts (managers). Other variables are defined previously. H3 predicts that the reduction in information asymmetry will be increasingly pronounced as the non-GAAP earnings adjustment increases. If H3 is correct, the change in adverse-selection cost should be negatively associated with RANKabsEXs. H3 predicts that β1 < 0.

5 Sample and descriptive statistics

We obtain data for adverse-selection cost from NASTRAQ intra-day trade and quote data. We adopt the procedures used in several studies (Barclay and Hendershott 2004; Chung et al. 2006; Huang and Stoll 1996) when cleaning the data and matching trades and quotes. (Details are available upon request.) Forecasted EPS, street EPS, and the number of analysts making forecasts are obtained from the unadjusted I/B/E/S database. We obtain earnings announcement dates, basic and diluted quarterly earnings per share before extraordinary items, and other accounting data from Compustat. Stock return data are from CRSP. Ted Christensen and Erv Black shared their hand-collected manager pro forma data for this study.

Our analysis centers on quarterly earnings announcements from Compustat with available NASTRAQ dataFootnote 6 (from 1999 to 2006 in the WRDS database). We first calculate adverse-selection cost on a daily basis, dropping any day with fewer than 30 trades for a stock (Lin et al. 1995). Then, for each quarterly earnings announcement, we find the mean daily adverse-selection cost over the pre- and post-announcement windows, separately.

The NASTRAQ database comprises 10,843 different firms represented at least once. Of those, 4878 firms appear at least once in Compustat and I/B/E/S. We restrict the study to firm-quarters with all data necessary to test our three hypotheses, including adverse-selection data, I/B/E/S forecasts and actual earnings data, CRSP return data, and Compustat data. We further require that all firm-quarters in the sample have at least three analyst forecasts in the pre- and post-announcement periods, at least five daily returns on CRSP in the pre- and post-announcement periods, and at least five valid observations on daily adverse-selection cost in each estimation window. We merge manager pro forma data to our dataset using Compustat GVKEY and CRSP PERMNO. The final sample is 21,327 firm-quarters and 2279 unique firms. Of those firms, 809 report pro forma earnings for at least one quarter, and 1702 have an I/B/E/S street earnings for at least one quarter.

Table 1 Panel A reports the number of observations (firm-quarters) by fiscal year. Over the entire sample period, analysts (managers) issue non-GAAP earnings in 45.57 (14.83) % of all firm-quarters. From 1999 to 2001, street and pro forma earnings increase as a percentage of the total earnings disclosures in a given year. Beginning in 2002, pro forma and street earnings become less popular until 2006. Panel B reports the number of firm-quarters by industry using an industry classification scheme similar to the classification in Barth et al. (1998). Street and pro forma earnings, as a proportion of the industry total, varies considerably across industries. For analysts and managers, the proportion of non-GAAP earnings is above the sample average for three industry groups (food; manufacturing: electrical equipment; and computers). The variability of non-GAAP earnings across industries justifies industry membership as a covariate in our selection model.

Table 2 Panel A reports descriptive statistics for variables related (primarily) to forecasted and actual quarterly earnings, classified by street vs. GAAP quarters for analysts and by pro forma vs. GAAP quarters for managers. On average, the market value of common equity and the number of analysts following a firm are larger for non-GAAP than GAAP quarters. Also, the average book-to-market ratio is higher for non-GAAP than GAAP quarters. We control for these three variables in the regression models that explain adverse-selection cost.

As expected, analysts’ street EPS ($0.140 median) is higher than the median EPS reported by Compustat ($0.070 primary and diluted). Similarly, managers’ median pro forma EPS ($0.130) is higher than the median EPS reported by Compustat ($0.060 primary and diluted). The mean absolute earnings adjustment, as a percentage of stock price, is 1.675 % for street earnings and 1.096 % for pro forma earnings. Forecast errors, based on earnings numbers reported by analysts and managers, are generally more favorable when non-GAAP earnings are reported. For example, when managers issue pro forma (GAAP) earnings, approximately 67.9 (58.1) % of firms beat the I/B/E/S forecast and 22.3 (25.5) % miss the forecast.

Table 2 Panel B reports mean and median statistics for information uncertainty, intra-day trading measures, and adverse-selection cost. Based on mean values, the Barron et al. (1998) measures of information uncertainty are higher in non-GAAP than GAAP quarters for analysts; however, the opposite is true for managers. For analysts and managers, median trade sizes and median trading frequencies are larger in non-GAAP than in GAAP quarters. The substantially greater market liquidity for non-GAAP quarters is a primary reason why, on average, effective spread and adverse-selection cost are lower in non-GAAP than GAAP quarters. These liquidity differences illustrate the importance of controlling for trading frequency. As expected, the mean and median effective spreads (cents per share) and adverse-selection cost (cents per share) decline in the post-announcement period relative to the pre-announcement period, consistent with a decrease in information asymmetry following earnings announcements.

Table 2 Panel C reports means and medians for variables in our selection model. As expected, the volatility of return on assets (STDDEVROA) and the frequency of special items (SPECITEMS) are larger, on average, in non-GAAP than in GAAP quarters for analysts and managers. Also as expected, non-GAAP quarters have more intangible assets (INTANGIBLES), a higher frequency of negative forecast errors for operating earnings (negOPFE), and a higher frequency of negative operating earnings (OPLOSS) than GAAP quarters. And non-GAAP quarters exhibit larger firm size (lnTA) and are less likely after SOX. However, contrary to expectations, market-to-book (MTB), and leverage (LEVERAGE) are higher in GAAP than in non-GAAP quarters.

Table 3 classifies the sample by the number of consecutive quarters that I/B/E/S issued GAAP or street earnings as of quarter t − 1. For each classification, Table 3 reports the mean probability of street and pro forma earnings for quarter t from our selection model and the actual frequency of GAAP and non-GAAP earnings reported in quarter t by analysts and managers. For example, in 849 cases, I/B/E/S issued a GAAP earnings number for exactly five consecutive quarters as of t − 1. For those 849 cases, the actual frequency of street (pro forma) earnings in quarter t is 139 (45), and the relative frequency of street (pro forma) earnings is 16.37 (5.30) %. By contrast, for the 602 cases where I/B/E/S reported street earnings for exactly five consecutive quarters at t − 1, the actual frequency of street (pro forma) earnings in quarter t is 487 (177), and the relative frequency is 80.90 (29.40) %. On average, the estimated probabilities of street and pro forma earnings in quarter t from our selection models increase monotonically as the consecutive quarters of I/B/E/S-issued GAAP (street) earnings as of quarter t − 1 decreases (increases). The results in Table 3 illustrate that the reporting choices by analysts and managers are not statistically independent, an issue we return to below.

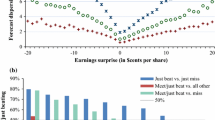

Figure 1 plots median daily adverse-selection measures from 20 days prior through 20 days after earnings announcements for street and GAAP quarters. (The plots for pro forma versus GAAP quarters resemble those in Fig. 1.) In Panel A, the median effective spread (ES) spikes upward just before and on the day of the earnings announcements and plummets immediately thereafter. Panel B reports a similar pattern for adverse-selection cost per share (ASC). At each point in event time, effective spread in Panel A and ASC in Panel B are lower for the street portfolio than the GAAP portfolio. The lower adverse-selection cost for the street portfolio reflects the generally larger size and greater liquidity of firms in the street portfolio compared to the GAAP portfolio. Panels A and B illustrate the importance of controlling for size and other factors that affect the levels of and the changes in adverse-selection cost.

Figure 1 Panel C plots the deviation of the daily median ASC from each portfolio’s 41-day median. Street quarters have a smaller spike than GAAP quarters on the day of the earnings announcements, consistent with earlier price discovery for street than GAAP quarters. Post-announcement period ASC is noticeably lower for both portfolios than their respective pre-announcement period ASC, consistent with earnings disclosures that reveal informed traders’ pre-announcement private information. Panel D plots the difference between the daily median ASC for the two groups (street minus GAAP). The dip in the plot series on the earnings announcement day is due to the larger increase in ASC for the GAAP portfolio compared to the street portfolio. Panel D does not clearly show whether the post-announcement decline in ASC differs between the street and GAAP portfolios.

6 Regression results

6.1 Results for H1 using OLS models

Our first set of tests, using the OLS model described in Sect. 4.4, examines whether adverse-selection cost in the pre-announcement period is positively associated with the probability of street and pro forma earnings as predicted by H1. In Table 4 Panel A, columns (a) and (b) report results for the full sample, separately for analysts and managers; columns (c) and (d) report the results for quarters when the disclosure choice changed from GAAP to non-GAAP or vice versa. We first discuss the full sample results in Table 4 Panel A and then turn to the restricted sample findings.

For analysts (managers), ProbNonGAAP it is the probability that I/B/E/S (managers) will issue street (pro forma) earnings for firm i at the quarter t earnings release. For analysts in column (a) and managers in column (b), the coefficient on ProbNonGAAP is positive and significant (p < 0.001), indicating that adverse-selection cost in the pre-announcement period is increasing as the probability of non-GAAP earnings (street or pro forma) increases. As expected, pre-announcement adverse-selection cost, ASCpre t , is positively associated with ASCpre t−1. This is consistent with firm-level effects that evolve slowly. Pre-announcement adverse-selection cost is also positively associated (p < 0.001) with the uncertainty of a firm’s public information (RankC), suggesting that information asymmetry is increasing with the underlying uncertainty intrinsic to a firm’s information environment.

For the full sample, adverse-selection cost is positively associated with stock price (lnMIDPOINT), as expected, and negatively associated with trading frequency (lnTradeFreq) and trade size (lnTradeSize). The negative coefficient for trading frequency (p < 0.001) is consistent with lower information asymmetry as market liquidity increases. However, the negative coefficient for trade size (p < 0.01) is inconsistent with larger trades as an indicator of a higher likelihood of informed trades. This outcome may not be entirely surprising because trade size may be a poor indicator for trades by sophisticated investors (Cready et al. 2014). We do find, as expected, that adverse-selection cost is negatively associated with market value of equity (lnMV) and book-to-market ratio (BTM), consistent with better information availability and less information asymmetry for larger firms and lower growth firms. The coefficients for ANALYSTS in columns (a) and (b) are, unexpectedly, positive (p ≤ 0.02)Footnote 7 and MBECQ t−1 is insignificant. Finally, firms with a forecasted loss (LOSS) have higher pre-announcement adverse-selection cost, as expected.

One concern with the full sample results is that the differences in the composition of firms in GAAP and non-GAAP quarters may influence the observed difference in adverse-selection cost (ASC). We partially address this issue by including lagged ASC as an independent variable. As an additional remedy, we restrict the analysis to firm-quarters where the disclosure choice for firm i in quarter t differs from the choice in quarter t − 1. These samples, identified separately for analysts (n = 4931) and managers (n = 2564), allow us to capture within-firm variation of ASC related to disclosure choice, per se, and reduce the concern that cross-sectional differences in ASC are driven by firm characteristics that lead some firms (or, their analysts) to typically report non-GAAP and other firms to typically report GAAP earnings. As reported in Table 4 Panel A, results for the restricted samples (columns (c) and (d)), show that the coefficient on the probability of non-GAAP earnings is not significant for analysts (p = 0.120) but is significant for managers (p = 0.002). The findings for managers are robust to our subsample test.

6.2 Results for H1 using treatment effect models

As an additional test of H1, we employ Heckman-type treatment effect models. The treatment effect models control for selection bias and capture the difference in pre-announcement adverse-selection cost between GAAP and non-GAAP quarters through the indicator variable NonGAAP it in the outcome equation. Because the actual disclosure choice (NonGAAP it ) is included in the outcome equation in Table 4 Panel B, our pre-announcement treatment effect models embody a perfect foresight assumption with respect to selection. All treatment effect models, including models in Table 5, exhibit a significant correlation between the error terms from the selection and outcome equations (Wald Chi square p values <0.001, untabulated), which suggests the potential for coefficient bias without control for self-selection.

We first discuss our selection model results. We find that the likelihood of non-GAAP earnings is positively and highly significantly associated with special items (SPECITEMS, p ≤ 0.001), with the log of total assets (lnTA, p ≤ 0.001) for analysts, and with sales growth (SALESGROWTH, p ≤ 0.001) for managers. These results, broadly speaking, are consistent with a greater likelihood of non-GAAP earnings when nonrecurring items are more likely. Earnings volatility (STDEVROA) is not significant. There is a highly significant decrease in the likelihood of non-GAAP disclosures following Sarbanes–Oxley (SOX, p ≤ 0.001) for analysts but not managers. Consistent with Table 3, the likelihood of street and pro forma earnings at quarter t increases with the consecutive quarters of I/B/E/S street earnings at t − 1 (NQ t−1, p ≤ 0.001) and decreases with the consecutive quarters of I/B/E/S GAAP earnings at t − 1 (GQ t−1, p ≤ 0.001) for all samples.

We find mixed evidence for the use of non-GAAP earnings to influence investor perception of firm performance. The likelihood of non-GAAP earnings is significantly higher for firms with negative forecast errors (negOPFE, p ≤ 0.001). At the same time, non-GAAP earnings is negatively associated with GAAP operating losses (OPLOSS, p < 0.004) for managers and insignificantly associated with GAAP operating losses for analysts. The evidence is also mixed with respect to whether non-GAAP disclosures are more likely when earnings have low informativeness. Intangible intensity (INTANGIBLES) is highly significant (p ≤ 0.001) for managers but not analysts, and market-to-book (MTB) and leverage (LEVERAGE) are significant (p ≤ 0.001) for analysts but not managers. The findings suggest that the selection decisions by managers and analysts differ.

We turn next to the results for our outcome models. The results for the control variables resemble those in our OLS models. The new and important results relate to the treatment effect variable, NonGAAP, and the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). In column (a), after controlling for selection bias, we observe higher adverse-selection cost in the pre-announcement period when I/B/E/S subsequently issues street EPS rather than unadjusted GAAP EPS (p ≤ 0.001). Similarly, in column (b), we observe higher adverse-selection cost when managers issue pro forma earnings rather than GAAP-only earnings (p ≤ 0.001). These findings are consistent with H1.

The coefficient on IMR is negative and significant (p < 0.001). Our interpretation of this finding relies on Li and Prabhala (2007), who argue that managers’ unobservable inside information influences their selection decisions and the related outcomes. In our case, this means that managers’ inside information affects their decision to provide non-GAAP earnings and also affects the pre-announcement adverse-selection cost. Under this interpretation, the negative coefficient on the inverse Mills ratio reflects the association between management’s inside information and pre-announcement adverse-selection cost, suggesting that higher levels of inside information are associated with lower levels of information acquisition by informed traders in the pre-announcement period. This result is reasonable if the precision of public information is diminishing as the amount of inside information increases. To clarify, let the total quantity of information (i.e., the sum of inside information and public information about a firm) be the best indicator of firm value. As the amount or precision of inside information increases, the relative precision of forthcoming public information with respect to firm value decreases. Because informed traders can profit most from public disclosures that most precisely reveal firm value, we would expect the existence of inside information to lower the incentive for informed traders to acquire private information in the pre-announcement period. A similar interpretation for IMR applies to street earnings, provided that analysts also hold “inside” information. We do not speculate on whether analysts’ private information resembles or differs from that held by management.Footnote 8

A limitation of the full sample results in columns (a) and (b) is that street and pro forma disclosure choices are positively correlated, which confounds the attribution of the differences in adverse selection between GAAP and non-GAAP quarters uniquely to street or pro forma earnings. This issue was raised earlier in Table 3. To further illustrate the problem, consider the two-way classification of manager and analyst disclosure selections in Table 4 Panel C. The two-way classification reports the number of observations and, in parentheses, the Pearson correlation between ProbSTREET t and ProbPROFORMA t (for each cell) from our selection models for analysts and managers, respectively. The two-way classification clearly shows that the selection of GAAP or street earnings by analysts is not (statistically) independent of the selection of GAAP or pro forma earnings by managers. The high Pearson correlations between the probability of street earnings and the probability of pro forma earnings for all cells in the two-way classification reflect this dependence.

Table 4 Panel B addresses the issue of statistical dependence through two restricted samples. In column (c), we restrict the analyst regression to the 18,164 firm-quarters when management did not report pro forma earnings. In those quarters, I/B/E/S issued GAAP (street) earnings 11,261 (6903) times. In column (d), we restrict the manager regression to the 9718 firm-quarters when I/B/E/S did issue street earnings. In those quarters, managers issued GAAP (pro forma) earnings 6903 (2815) times.

In Table 4 Panel B column (c), we again find that adverse selection in the pre-announcement period is higher when I/B/E/S issues street earnings rather than GAAP earnings (p ≤ 0.001). These findings isolate the incremental adverse-selection cost attributable to the (anticipated) disclosure by analysts of street earnings instead of GAAP earnings for a sample of firm-quarters where management reports GAAP earnings only. Similarly, in column (d), we find that adverse selection is higher in the pre-announcement period when management issues pro forma earnings rather than GAAP earnings only (p ≤ 0.001) for a sample of firm-quarters where analysts report street earnings. Thus, even in cases where analysts report street earnings, we can attribute significantly higher adverse-selection cost to the (anticipated) supplemental disclosure of pro forma earnings by managers.

6.3 Post-announcement period

Despite our efforts, the differences in information asymmetry between GAAP and non-GAAP quarters in Table 4 may result from a failure to control adequately for important systematic differences between the typical GAAP and non-GAAP firm. Under that view, empirical support for the first hypothesis may not reflect the market’s perception of the informativeness of non-GAAP earnings but rather other fundamental differences between the typical GAAP and non-GAAP firm. Our second set of tests largely avoids this criticism by using changes in adverse selection as the dependent variable, in effect making a firm its own control through a difference-in-differences approach. Additionally, we continue to employ treatment effect models to control for selection bias.

6.3.1 Results for H2

Table 5 examines whether the post-announcement change in information asymmetry (ASCpost less ASCpre) differs between GAAP and non-GAAP quarters. As discussed earlier, if non-GAAP earnings numbers reveal more pre-announcement private information and facilitate a faster resolution of undiscoverable information than GAAP earnings alone, we would expect a larger post-announcement reduction in adverse-selection cost in non-GAAP than GAAP earnings quarters. H2 predicts that the post-announcement reduction in adverse-selection cost will be more pronounced for non-GAAP than GAAP quarters.

Tables 4 and 5 use the same selection model and the selection model results are similar for the two tables. Consequently, we do not revisit the selection model results. In Table 5, as in Table 4, the inverse Mills ratio from each selection model is a covariate in its respective outcome equation. Thus, in Table 5, the outcome equations control for changes in adverse-selection cost associated with unobserved factors that affect both the decision to issue non-GAAP earnings and changes in adverse-selection cost, allowing a better identification of the extent to which post-announcement changes in information asymmetry depend on analyst and manager disclosure choices per se.

In our outcome models, the coefficient on ASCpre is −0.251 (p ≤ 0.001) in columns (a) and (b). This finding indicates that, after controlling for other factors affecting the change in adverse-selection cost, there is a 25 % reduction in adverse-selection cost on average from the pre- to the post-announcement period. This outcome is expected if scheduled disclosures through financial statements stimulate private information search in advance of those disclosures and if information asymmetry is resolved following the public dissemination of financial statements.

In Table 5, the difference between the change in adverse-selection cost for GAAP and non-GAAP quarters is modeled as a fixed constant as measured by the coefficient on the variable, NonGAAP t . For analysts and managers, the coefficient on NonGAAP t is negative and significant (p < 0.001) indicating that, on average, the post-announcement reduction in adverse-selection cost is significantly more pronounced when analysts (managers) issue street (pro forma) earnings at the earnings announcement than when they do not. We interpret non-GAAP disclosures as a mechanism for disclosing price-relevant private information, consistent with a significantly greater reduction in information asymmetry in non-GAAP than GAAP quarters.

We find a positive and significant (p < 0.001) coefficient on IMR. Again, we interpret the coefficient on the inverse Mills ratio as the effect of undisclosed inside management information on the post-announcement change in adverse selection. Higher levels of inside information would be expected to reduce the precision of accounting information with respect to the value of the firm and thus temper the overall reduction in post-announcement information asymmetry. The positive coefficient on IMR is consistent with this inside information interpretation.Footnote 9

We also report restricted sample tests in Table 5, where the restrictions are the same as those in Table 4 Panel B. Consistent with the full sample results in Table 5, the coefficient on the treatment variable, NonGAAP, is negative and significant (p < 0.001). The result for the manager sample, which is restricted to firm-quarters where analysts reported street earnings, is particularly interesting. The negative coefficient for NonGAAP for that sample suggests that, when managers disclose pro forma earnings rather than GAAP earnings, there is a reduction in information asymmetry that is incremental to the reduction in information asymmetry that occurs when analysts report street earnings. Additionally, in an untabulated analysis for the full sample, we find that the reduction in adverse-selection cost is larger for pro forma disclosures than street earnings disclosures. Specifically, the 95 % confidence interval for the coefficient on NonGAAP t for pro forma earnings (−0.305 to −0.181) is smaller than the same confidence interval for street earnings (−0.148 to −0.083). Collectively, our results suggest that pro forma earnings are incrementally informative to I/B/E/S street earnings. Under the view that pro forma disclosures communicate a subset of managers’ previously private information and that street earnings similarly communicate a subset of analysts’ previously private information, our results suggest that, with respect to firm valuation, managers’ private information is more informative than analysts’.

Next, we consider our control variables in our outcome models in Table 5. Results are similar across models and samples. As expected, the reduction in adverse-selection cost is more pronounced (p ≤ 0.001) as the absolute forecast error (absFEs) increases. This finding is reasonable because forecast errors represent earnings information not in analysts’ forecasts. As the absolute forecast error increases, the earnings announcement communicates increasing levels of previously nonpublic information and reduces information asymmetry.

The change in adverse-selection cost is negatively associated with the changes in trade frequency and positively associated with the change in price (chglnMIDPOINT). These results are consistent with expectations because post-announcement increases in trade frequency and decreases in price suggest more liquidity and lower adverse-selection cost. However, the negative association between change in adverse-selection and trade size is unexpected because the result suggests that adverse selection cost decreases as trade size increases. This anomalous finding for trade size resembles the anomalous finding for trade size in Table 4, indicating that trade size is a poor proxy for informed trading. We find that loss firms show a steeper decline in adverse selection than profit firms (p ≤ 0.011), consistent with the strong correlation between predicted and actual losses and the relatively high pre-announcement adverse selection for firms with forecasted losses. Finally, there is an insignificant association between the change in adverse-selection cost and the change in information uncertainty (chgRankC t and chgRankD t+1).

6.3.2 Results for H3

H3 predicts that the post-announcement reduction in adverse-selection cost will be larger when the absolute value of non-GAAP earnings exclusions is larger. Table 6 is restricted to street quarters for analysts and pro forma quarters for managers. The table reports findings for non-GAAP earnings exclusions (EX or EX′) based on two different benchmarks for non-GAAP earnings. In panel A, exclusions (EX) are found as non-GAAP EPS minus GAAP EPS before extraordinary items. EX may be comprised of special items or line items included in operating income. In Panel B, exclusions (EX′) are found as non-GAAP EPS minus GAAP operating EPS (oepsxq) (Black and Christensen 2009). Under the assumption that special items are always excluded from street and pro forma earnings, EX′ is limited to revenues and expenses that are part of GAAP operating income. For street and pro forma earnings, separately, we substitute integer ranks (0–99) for the absolute-value of price-scaled nonzero earnings adjustments, such that a one-point increase in the ranking variable, RANKabsEXs, represents a one-percentile increase in the magnitude of the per-share non-GAAP earnings adjustments (EX or EX′) scaled by stock price. We use ranked values to allow simpler interpretation of the economic significance of non-GAAP exclusions and to avoid the influence that outliers might otherwise have on the results.

In Table 6, Panel A, columns (a) and (b), the coefficients on ASCpre indicate that adverse-selection cost decreases, on average, by approximately 26 % from the pre-announcement level for analysts and managers, after controlling for other factors. This finding is comparable to the 25 % reduction reported in Table 5 for the full sample. The coefficient on RANKabsEXs for street (pro forma) earnings indicates that post-announcement adverse-selection cost per share decreases, on average, by about 3.4 (3.2) % when the non-GAAP earnings adjustment (EX) as a proportion of market value increases from the 25th to the 75th percentile.Footnote 10 As a sense of the size of the non-GAAP adjustments in economic terms, the 25th percentile for the absolute value of the street EPS adjustment as percentage of share price is 0.13 %, and the 75th percentile is 1.17 %. Thus, for the street earnings, when the absolute value of the pro forma adjustment increases by 1.04 percentage points of share price, adverse-selection cost decreases by 3.4 %.Footnote 11

The informativeness of non-GAAP earnings may be sensitive to whether earnings adjustments increase or decrease earnings (Abarbanell and Lehavy 2007). Thus we conduct another test that separately analyses income-decreasing adjustments (where EX = non-GAAP EPS − GAAP EPS < 0) and income-increasing adjustments (where EX = non-GAAP EPS − GAAP EPS > 0). For street earnings in column (c), the coefficient for RANKabsEXs is negative for income-decreasing (coefficient = −0.058, p = 0.087) and income-increasing earnings adjustments (coefficient = −0.107, p ≤ 0.001). The coefficient for positive (income-increasing) adjustments is smaller than the coefficient for negative (income-decreasing) adjustments (p = 0.053, not tabulated). In other words, the reduction in post-announcement adverse-selection cost for street earnings is significantly more pronounced for income-increasing than for comparable income-decreasing adjustments.

For pro forma earnings in column (d), the coefficient for RANKabsEXs is again negative for income-decreasing adjustments (coefficient = −0.090, p = 0.089) and income-increasing earnings adjustments (coefficient = −0.087, p = 0.019). The reduction in post-announcement adverse-selection cost is statistically indistinguishable (p = 0.986, not tabulated) for comparable income-increasing and income-decreasing pro forma adjustments. Overall, the results in Table 6 Panel A suggest that realistically observable cross-sectional differences in the dollar amount of non-GAAP adjustments are associated with economically significant and statistically distinguishable effects on the extent of the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry.

Results in Panel B for operating income exclusions (EX′) resemble those in Panel A for total exclusions (EX). In Panel B columns (a) and (b), there is a negative association between the change in post-announcement adverse-selection cost and the rank of the absolute operating income exclusion for analysts (p < 0.001) and managers (p = 0.099). These results indicate that, for analysts, the reduction in information asymmetry is increasingly pronounced as the absolute value of the exclusion increases when exclusions are restricted to revenues and expenses classified as part of operating income. When we further split operating income exclusions into income-decreasing and income-increasing for analysts, the coefficient for RANKabsEXs is negative for both (income-decreasing: p = 0.097; income-increasing: p ≤ 0.001), and the coefficient for income-increasing or positive adjustments is smaller than the coefficient for income-decreasing or negative adjustments (p = 0.041, not tabulated). In short, for analysts, the results restricted to operating income exclusions in Panel B resemble those for total income exclusions in Panel A.

In Panel B for managers, we find negative coefficients for income-decreasing (p = 0.429) and income-increasing exclusions (p = 0.093). Considering the insignificant coefficient for income-decreasing operating-income exclusions in Panel B and the (marginally) significant coefficient for the corresponding analysis in Panel A, we conclude that special items may be responsible for Panel A’s findings for income-decreasing total exclusions for managers.

In Table 6, Panel C, we examine whether the post-announcement reduction in adverse selection is sensitive to the effect that income-increasing exclusions have on the sign of the forecast error. Specifically, we examine whether the association between the change in adverse selection and the magnitude of income-increasing exclusions differs when the total exclusion flips the sign of the forecast error, from “miss” to “meet-or-beat,” compared to total exclusions that leave the sign of the forecast error unchanged. The rationale behind this additional test is that income-increasing exclusions that flip the sign of the forecast error may be driven primarily by incentives or pressures to meet or beat earnings forecasts rather than incentives to improve the informativeness of earnings disclosures.

To examine whether an opportunism effect is present, we restrict the analysis to non-GAAP (street and pro forma) quarters with income-increasing total exclusions (EX > 0). We then form an indicator variable, FE_FLIPS, equal to 1 if the exclusion flips the forecast error from miss to meet or beat. Specifically, when GAAP earnings are less than forecasted earnings (miss) and non-GAAP earnings are greater than or equal to forecasted earnings (meet or beat), then FE_FLIPS is equal to 1.Footnote 12 Of the 9718 street quarters, 7558 firm-quarters have income-increasing total exclusions (EX > 0). Of those, 3124 do not flip the forecast error (FE_FLIP = 0), and 4434 do flip the forecast error (FE_FLIP = 1). Of the 3163 pro forma quarters, 2777 have income-increasing total exclusions. Of those, 1139 flip and 1638 do not flip the forecast error.

In Panel C, the coefficient on the interaction term, FE_FLIPS × RANKabsEXs captures whether the association between post-announcement changes in adverse-selection cost and the magnitude of the non-GAAP exclusions differs when income-increasing exclusions flip the forecast error (from miss to meet or beat) compared to cases when exclusions do not change the sign of the forecast error. In Model 1, RANKabsEXs is the rank of total exclusions (i.e., ranks of EX where EX > 0). For Model 2, RANKabsEXs is the rank of operating exclusions (EX′) for the subset of non-GAAP quarters where EX > 0 and EX′ > 0. Model 2 examines whether the association between changes in adverse selection and the magnitude of GAAP operating expense exclusions differs when operating expense exclusions contribute to flipping the forecast error. In all four columns, the coefficient on the interaction term is insignificant (p ≥ 0.553), showing no evidence of opportunism effects for total exclusions or for operating expense exclusions.

7 Conclusion

We examine whether the level of information asymmetry before earnings announcements and the change in information asymmetry after earnings announcements differ in quarters where analysts and managers issue street earnings or pro forma earnings, respectively, compared to quarters when they refrain from reporting a non-GAAP EPS number. In the pre-announcement period, we find that the adverse-selection component of the bid-ask spread is significantly and positively associated with the probability that I/B/E/S will issue a street earnings number or that managers will issue a pro forma earnings number. These findings are consistent with an increase in private information searching and heightened trading on private information when sophisticated investors (informed traders) expect non-GAAP earnings at the earnings announcement. The findings are consistent with the prospect of higher earnings precision at the earnings announcement when street or pro forma earnings are more likely.

Additionally, we find that the post-announcement reduction in adverse-selection cost is more pronounced in street and pro forma quarters than in GAAP-only quarters. We also find that the post-announcement reduction in adverse-selection cost is larger when the magnitude of the non-GAAP earnings adjustment (the absolute difference between GAAP and non-GAAP earnings) is larger. The latter result holds for street and pro forma earnings and for income-increasing and income-decreasing earnings adjustments. The findings suggest that street and pro forma earnings adjustments help to narrow the information gap between informed and uninformed traders. One avenue for additional research is whether non-GAAP disclosures are associated with capital market effects such as the cost of capital or post earnings-announcement drift.

Our study is subject to certain limitations. While we find evidence that the reduction in information asymmetry is more pronounced when managers or analysts choose to report non-GAAP earnings and that the reduction in information asymmetry is increasing with the magnitude of non-GAAP earnings adjustments, we do not identify why those associations occur. It may be that non-GAAP earnings adjustments identify elements of earnings that have different relevance or persistence with respect to firm value, as we propose. However, it may also be that overall reporting quality is better when analysts or managers disclose non-GAAP earnings and that our findings reflect a difference in the overall quality of disclosures rather than a difference specifically related to non-GAAP disclosures. Also, we have not considered whether non-GAAP adjustments are identified in the footnotes to the financial statements. Adjustments that are typically disclosed in the footnotes may be less informative than adjustments that are less commonly disclosed.

Our interpretation of our results assumes that markets are (reasonably) efficient. In an efficient market, information with higher precision with respect to firm value commands a higher price. Thus, under the assumption of an efficient market, our results suggest that the expectation of street or pro forma earnings increases private information search because non-GAAP earnings more precisely reflect a firm’s underlying value. However, markets may be consistently inefficient. In that case, private information search might focus on non-GAAP earnings simply because naïve investors may view non-GAAP earnings as more value relevant than GAAP earnings. Thus sophisticated investors might earn positive returns to private information search, independent of the relevance of non-GAAP earnings to a firm’s intrinsic value.

Notes

I/B/E/S (2001, p. 7) states: “There is no ‘right’ answer as to when a non-extraordinary charge is nonrecurring or non-operating and deserves to be excluded from the earnings basis used to value the company’s stock. We believe the ‘best’ answer is what the majority wants to use, in that the majority basis is likely what is reflected in the stock price.” Lambert (2004), however, points out the difficulty surrounding the classification of an item as “nonrecurring.”

The NASDAQ saw dramatic changes in the early 2000s because of the growth of electronic communication networks, which enable investors to submit anonymous limit orders and trade directly with each other (Barclay et al. 2003).

In robustness checks using a street selection model excluding five variables related solely to earnings informativeness and missed earnings targets (i.e., INTANGIBLES, MTB, LEVERAGE, negOPFE, and OPLOSS), we find results for analysts (untabulated) very nearly identical to our reported findings.

In robustness tests, we also included an indicator variable for Regulation G in the selection model. That variable is not significant in any case.

Equation (3) does not include changes in lnMV, ANALYSTS, and BTM because size, number of analysts, and book-to-market for any firm-quarter are essentially fixed. Additionally, ASCpre in Eq. (3) already reflects size, number of analysts, and book to market. Omitting size, however, may be a special concern because small firms typically have more informative earnings announcements than large firms. We reran the model including size (lnMV). Size is not significant, and its inclusion does not affect any inferences.

We choose NASTRAQ intra-day data over TAQ data for three reasons. First, NASTRAQ permits accurate matching of trade and quote data because actual trade execution times are known; TAQ stamps a trade based on when it is reported rather than when it is executed. Second, unlike TAQ, NASTRAQ does not round transaction sizes and prices.

When we drop firm size (lnMV) from the regression model, we find a negative coefficient on ANALYSTS (p ≤ 0.001) in all regressions (not tabulated), consistent with lower adverse-selection cost as analyst coverage increases.