Abstract

Aims

The long-term effects of COVID-19 (Long COVID) include 19 symptoms ranging from mild to debilitating. We examined multidimensional correlates of Long COVID symptom burden.

Methods

This study focused on participants who reported having had COVID in Spring 2023 (n = 656; 85% female, mean age = 55, 59% college). Participants were categorized into symptom-burden groups using Latent Profile Analysis of 19 Long-COVID symptoms. Measures included demographics; quality of life and well-being (QOL); and COVID-specific stressors. Bivariate and multivariate associations of symptom burden were examined.

Results

A three-profile solution reflected low, medium, and high symptom burden, aligning with diagnosis confirmation and treatment by a healthcare provider. Higher symptom burden was associated with reporting more comorbidities; being unmarried, difficulty paying bills, being disabled from work, not having a college degree, younger age, higher body mass index, having had COVID multiple times, worse reported QOL, greater reported financial hardship and worry; maladaptive coping, and worse healthcare disruption, health/healthcare stress, racial-inequity stress, family-relationship problems, and social support. Multivariate modeling revealed that financial hardship, worry, risk-taking, comorbidities, health/healthcare stress, and younger age were risk factors for higher symptom burden, whereas social support and reducing substance use were protective factors.

Conclusions

Long-COVID symptom burden is associated with substantial, modifiable social and behavioral factors. Most notably, financial hardship was associated with more than three times the risk of high versus low Long-COVID symptom burden. These findings suggest the need for multi-pronged support in the absence of a cure, such as symptom palliation, telehealth, social services, and psychosocial support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had far-reaching effects on mortality and morbidity among people across the globe. As of April 13, 2024, there have been 1,188,991 COVID deaths in the United States (US) [1]. An estimated 10–15 million individuals in the US are affected by a new chronic condition that occurs within 2 months of the initial COVID illness and can last weeks, months or even years after infection [2, 3]. Referred to as post-acute syndrome of COVID-19 or long COVID (Long COVID) [3,4,5], this condition can impact every organ system [6], with symptom presentation varying across individuals. The Centers for Disease Control notes a list of 20 “commonly reported” symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating, with up to 200 Long COVID symptoms identified [2]. Some of the symptoms are similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome [7]. The duration of Long COVID is currently unknown and there is no treatment for it yet, with current recommendations focusing on symptom management and remaining up-to-date on COVID vaccines [7].

The phenotypes of Long COVID are numerous, highlighting complex presenting and predisposing features [8]. Many studies documented a higher risk of Long COVID among females [9,10,11,12,13,14], as well as a higher risk if the individual had five or more symptoms in the first week of COVID [10, 12, 15], had more severe acute COVID [13], or had been hospitalized for COVID [15]. Higher risk is associated with older age [9, 10, 12], and a higher body mass index [10]. Long COVID is also more likely in the context of pre-existing medical conditions [12, 13, 15, 16], including sleep problems [14, 17], fatigue [14], autoimmune disorders [18], respiratory and gastrointestinal conditions [18], and depression, anxiety [11, 14, 19], or somatoform disorders [19]. Pulmonary fibrosis, normally a rare condition [20], has been documented in 40% of hospitalized COVID survivors [13]. Additional conditions have been established to develop post-COVID, such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome [21].

Long COVID can have detrimental effects on both physical and mental health [22], which can co-occur [23]. Long-term impairments in cognitive functioning have also been documented [14]. Cognitive functioning deficits appear to be more likely in males [24], in those with fewer years of education [14], and with higher post-traumatic stress, anxiety or depression [25].

Given the well-documented disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on marginalized groups [26,27,28,29], it is likely that the experience of Long COVID intersects with social determinants of health [9]. Social determinants of health are defined by the World Health Organization as the environmental factors that influence health outcomes, encompassing economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies and political systems [4, 9]. In addition to non-modifiable characteristics such as age, sex assigned at birth, race, and pre-existing conditions, social determinants of health involve structural and modifiable variables such as employment, income, community characteristics [9], and psychological mechanisms [30]. A recent systematic review of risk factors for Long COVID highlighted a greater risk of adverse events for racial and ethnic minorities, as well as heightened risk from decreased family earnings and increased family-caregiver responsibilities [9]. The pandemic has particularly affected people’s ability to socially connect with others, which may have increased their risk of Long COVID [31]. Indirect measures of social-support-related factors have documented associations with long COVID, such as being previously married, greater loneliness, and less reported social support about a year into the pandemic [31]. Long COVID may further exacerbate this social disconnection by dint of being too sick to engage in activities [32] and also having adopted coping strategies that distance one from others (e.g., disengagement), or that make one less enjoyable to be around (e.g., emotion-focused coping such as venting or blaming) [33]. Such maladaptive coping strategies also lead to worse quality of life (QOL), anxiety, and depression [33]. Individuals with long COVID also often face stigma from those around them in both the community and medical settings [34].

The present study built on this growing evidence base by examining correlates of long COVID symptom burden across multiple dimensions. These dimensions included well-studied factors such as sociodemographic, QOL, and psychological well-being. They also included COVID-specific factors evident from the beginning of the pandemic (e.g., risk-taking, financial challenges, healthcare disruption, interpersonal concerns), and those that emerged later in the pandemic (e.g., perceived changes in priorities and social norms). We sought to understand what differentiated those individuals with higher Long-COVID symptom burden with an eye toward identifying modifiable risk factors possibly amenable to intervention.

Methods

Sample and design

This study focused on the fourth, final data collection of a quasi-experimental longitudinal cohort study of the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, while including baseline demographic data on variables only collected once (i.e., unlikely to change). The final data were collected between January 19 and April 12, 2023. Study participants were recruited via Rare Patient Voice and Ipsos Insight. By recruiting from two panel research company sources, we were able to yield a general-population sample of United States adults who were heterogeneous in terms of health (i.e., Rare Patient Voice specializes in rare and chronic disease samples; IPSOS specializes in general population samples with or without more common health conditions) and nationally representative in terms of age distribution, gender, region, and income (i.e., IPSOS specifically stratified sampling to ensure these nationally representative distributions). Participants were not paid monetarily for their participation. Eligible participants were age 18 or older, able to complete an online questionnaire, and able to provide informed consent. Additionally, the present work focused on the subset of individuals who reported having had COVID at least once to support the attribution of symptom burden to Long COVID.

The survey was administered through the secure Alchemer engine (www.alchemer.com), which is compliant with the United States Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the WCG Independent Review Board (#2021164), and all participants provided informed consent prior to beginning the survey.

Measures

Demographic characteristics included year of birth to compute age, gender, with whom they live, cohabitation/marital status, race, ethnicity, education, height and weight (to compute body mass index), reported difficulty paying bills, employment status, smoking status, year of chronic illness/comorbidity diagnosis if applicable, number of comorbidities, and whether they were a patient, caregiver, both, or neither.

COVID-specific clinical characteristics included whether/how many times the individual had COVID, COVID vaccination and booster history, whether they believed they had Long COVID, perceived knowledge about Long COVID, whether they had seen a healthcare provider for a Long COVID evaluation, and whether they had received treatment for Long COVID from a healthcare provider.

Long COVID symptom burden was assessed using a set of 20 questions from the Centers for Disease Control website [2]. One item regarding change in menstrual cycles was only pertinent to individuals who menstruate. Response options ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), with a Neutral option given a score of 3.

COVID-Specific Variables included selected items compiled by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research and the NIH Disaster Research program [35]. Supplemental Text provides full description of the COVID-specific variables, and supplemental Tables 1 and 2 provide a full listing of the items and the alpha reliability coefficients for each COVID-specific index:

QOL was assessed using the Patient-Reported Outcome Information System (PROMIS)-10 with subscales for physical health and mental health [36], and the NeuroQOL Adult Applied Cognition Executive Function and General Concerns short-forms v1.0 [37]. Well-Being was assessed using the NeuroQOL Adult Positive Affect and Well-Being 7-item short-form [37]; the DeltaQuest Wellness Measure [38]; and the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Environmental Mastery subscale 7-item version; [39].

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the demographic, long COVID symptom-burden items, COVID-specific behaviors, and QOL variables. To address selection bias between those included versus excluded from the present study (i.e., those who reported having had COVID (analytic sample) as compared to those who reported never having had COVID), group differences in demographic variables were compared using chi-squared analyses for categorical variables and analysis of variance models for continuous variables. As reported in an earlier paper [40], data reduction (factor analysis with varimax rotation) was used on the closed-ended questions about perceived changes in priorities, social norms, and life stress (see Supplemental Table 2). A cut-point of 0.50 was used for including an item in a factor score, corresponding to medium loadings [41]. For the present work, all COVID-specific variables and QOL variables were scored and/or transformed to be on a T-score metric, with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10, for ease of comparability and interpretability.

Latent profile analysis (LPA) [42] was used on 19 of the 20 the Long COVID symptom-burden items. Because the item regarding change in menstrual cycles would only have been pertinent to individuals who currently menstruate, it was not included in the LPA analysis. LPA is a person-centered method, in contrast to a variable-centered method such as factor analysis. It was used to identify subsets of persons with shared characteristics (i.e., severity of Long COVID symptoms) using all but the menstrual-change item from the original CDC listing so that all items were relevant regardless of sex. We tested models of one through eight profiles and selected the best fitting model based on a combination of criteria including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) statistics, with lower values being better; the Lo Mendell Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) results which evaluates whether a model with k + 1 classes offers an improved fit over a model with k classes; the entropy statistic, with higher values being better; the expected proportion of individuals in each class; and the face validity of the profiles [43]. Mplus was used to estimate the most likely profile for each person.

Bivariate analyses

We used the profiles resulting from the final LPA model to examine bivariate relationships between the profiles and the set of demographic, COVID-specific, and QOL variables described above, using chi-squared analyses for categorical variables and analysis of variance models for continuous variables. Effect sizes (ES) were used to facilitate interpretation, using Cohen’s cut-offs for explained variance (eta2) [44].

Multivariate analyses

We implemented a series of multinomial logistic regression models to examine the unique contribution of the demographic variables and COVID-specific factors to Long COVID symptom burden. The dependent variable was symptom-burden profile group (created using LPA as described above), with Low Symptom Burden as the referent. First, all demographic variables were tested simultaneously and only the significant variables were retained. Second, the COVID-specific factors were tested separately by domains corresponding to Challenges; Interpersonal; Perceived Changes in Priorities and Norms; and Stress. Third, the significant variables from each domain were tested simultaneously (penultimate model) and then only statistically significant variables across all domains were retained in the final model. This modeling approach for winnowing down the number of variables retained across multiple domains is similar to one recommended by Hosmer and Lemeshow [45]. In contrast to the bivariate analyses which were done with a primarily descriptive goal, the multivariate models were done with the goal of identifying unique contributions of the variables that assessed distinct constructs from the symptom-burden profiles. Accordingly, QOL and well-being outcomes were not considered in this multivariate model because they assessed constructs too similar to the symptoms underlying the symptom-burden profiles. (For further clarification, see Wilson and Cleary’s 1995 conceptual model [46] to clarify how symptoms, functional status, general health perceptions, and overall quality of life are proximal concepts.) Results will be presented in descending order of the magnitude of the odds ratio (OR) for retained predictors. Even though this is a cross-sectional study, we will use the terms “risk” and “protective” factors to highlight circumstances and experiences associated with vulnerability within groups most affected by Long COVID. Further, it should be noted that while COVID-specific variables were all standardized and thus on the same T-score metric, age and comorbidities were not, so the ORs for the latter two would not be directly comparable to those from the COVID-specific variables.

Statistical analyses were implemented using IBM SPSS version 29 [47], Mplus version 8.8 [48], and Microsoft Excel.

Results

Sample

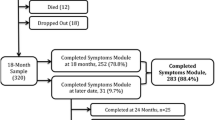

The final follow-up study sample included 1197 individuals. As reported in our earlier paper [40], this sample reflects 25.3% of the baseline sample (n = 4757), 69.1% of the follow-up 1 sample (n = 1734), and 95.5% of the follow-up 2 sample (n = 1255). A comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the overall (baseline) study sample and the participants of this final follow-up data collection revealed that the 1197 retained study participants were less likely to report difficulty paying bills, were more likely to report having a college or postgraduate degree, and were older [40]. Compared to those who had never had COVID, and were thus excluded from the present study, the sample was younger, more likely to be a caregiver, less likely to be living alone, endorsed more difficulty paying bills, were more likely to be employed, and less likely to have completed college or more education (see Supplemental Table 3). In terms of reported comorbidities, the study sample compared to those who never had COVID were less likely to report comorbidities of back pain, high blood pressure, cancer, or kidney disease, and more likely to report comorbidities of depression and/or asthma (see Supplemental Table 3). As noted above, analysis for the present work focused on male or female identifying participants who reported having had COVID at least once (n = 656, 54.8% of the final follow-up sample). The alpha reliability of the COVID-specific indices was generally acceptable, but low for the indices with only two items—Maladaptive Coping and Substance Use Increase – which is not uncommon (Supplemental Table 1). The descriptive statistics on the demographic, COVID-specific characteristics, and symptom-burden items for the study subsample are provided in Supplementary Tables 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

Latent profiles

The three-profile model had the best model fit statistics and made conceptual sense, reflecting low, medium, and high symptom burden, with the low symptom burden group likely not having Long COVID. Figure 1 shows the mean symptom endorsement across the 19 listed symptoms by symptom-burden profile. Notably, the high symptom-burden profile had peaks for fatigue, joint or muscle pain, and a new health problem, whereas the medium symptom-burden profile peaks comprised these symptoms, albeit at lower levels of endorsement, as well as brain fog, sleep problems, and depression/anxiety (Fig. 1).

Symptom-burden profiles derived from latent profile analysis. The item response options are shown on the y-axis, with a solid black line at “3” reflecting “Neutral” endorsement. Item means above the “Neutral” endorsement would thus reflect people in this group reporting having the symptom, whereas means below the line would reflect not having the symptom

Bivariate analyses

Results of bivariate analyses comparing the three symptom-burden profile groups revealed many differences. Table values were conditionally formatted to highlight the small, medium, and large ES of the magnitude of eta2 estimates. More color saturation reflects larger ES. To facilitate the reader’s task, results will be presented in order of ES, from large, to medium, to small.

In terms of demographic differences (Table 1), people in the high symptom-burden group were more likely to report more comorbidities (medium ES); being of younger age, higher body mass index, being both patient and caregiver, never being married, having greater difficulty paying bills, being disabled from work, and not having a college degree (all small ES). Males were more likely to be in the low symptom-burden group (small ES). There were no symptom-burden group differences on time since diagnosis, race, Hispanic ethnicity, whether one lived alone, or smoking/vaping status.

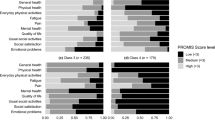

Bivariate analyses comparing COVID-specific clinical characteristics (Table 2; Fig. 2) revealed that symptom-burden profile membership aligned with the participant’s belief that they have Long COVID (large ES) and with Long-COVID diagnosis confirmation and treatment by a healthcare provider (both small ES). People in the high symptom-burden group reported having had COVID multiple times (small ES). In terms of perceived knowledge about Long COVID, people in the low symptom-burden group were more likely to report being moderately knowledgeable whereas those in the medium symptom-burden group were more likely to report being slightly knowledgeable (small ES). There were no symptom-burden group differences on COVID vaccination and booster history.

Regarding COVID-specific variables, bivariate analyses revealed that people in the higher symptom-burden group were more likely to report greater Financial Hardship, Worry, Financial-Hardship Stress, and Health/Healthcare Stress (all large ES; Table 3; Fig. 2), and they were more likely to report greater Healthcare Disruption, Maladaptive Coping, Family Relationship Stress, and Racism/Inequity Stress, and Less Social Support (all medium ES). Additionally, they were more likely to report engaging in more Risk-Taking Behavior, such as going out socially, but also more Protection, such as wearing masks in public (both small ES). They also reported more Interpersonal Conflict and less Salutogenic Coping (both small ES). They reported a similar Substance Use Increase score as the low symptom-burden group, but greater than the medium symptom-burden group (small ES).

In terms of perceived social changes, the high symptom-burden group reported greater endorsement of the importance of Inner Life and Relationships, lower Confidence in Public Health Strategies for Preventing COVID, and Higher Perceived Public Incivility Due to COVID (all small ES). With regard to QOL and well-being outcomes, the high symptom-burden group reported substantially worse physical health, mental health, cognitive functioning, positive affect/well-being, wellness, and environmental mastery (all large ES; Table 3; Fig. 2).

Multivariate analyses

The full output of the series of multivariate modeling is provided in Supplemental Tables 7 and 8, and the final model is shown in Table 4. Risk factors for being in the high symptom-burden group included Financial Hardship, Worry, Risk-Taking, Comorbidities, Health/Healthcare Stress, and younger age (ORs 3.44, 1.72, 1.67, 1.34, 1.10, and 0.97, respectively). In contrast, Social Support was protective against being in the high symptom-burden group (OR 0.67). As a person’s age increases by one year, the probability of being in the medium symptom-burden group relative to the low symptom-burden group decreases by 3%. Further for each additional comorbidity, a person is 34% more likely to be in the medium symptom-burden group relative to the low symptom-burden group. Figure 3 illustrates these findings with a line graph such that ORs above the dotted line reflect risk factors and those below reflect protective factors.

Risk factors for being in the medium symptom-burden group were similar in order but smaller in magnitude, with the exceptions that Risk-Taking and Social Support were not statistically significant, whereas lower Substance Use Increase was a protective factor (OR 0.72). As a person’s age increases by one year, the probability of being in the medium symptom-burden group relative to the low symptom-burden group decreases by 2%. Further for each additional comorbidity, a person is 15% more likely to be in the medium symptom-burden group relative to the low symptom-burden group.

Discussion

The present study findings highlight the importance of social determinants of health and social capital in the Long COVID symptom experience. While bivariate analyses pointed to similar demographic risk factors for higher Long COVID symptom burden as found in numerous other studies, many of these demographic characteristics were dropped from the multivariate model because they shared variance with other variables. For example, the only demographic variable retained in the final model was age (Table 4), whereas role, body mass index, gender, education, smoking status, marital status, financial difficulty, and employment status were not retained (Supplemental Table 4). Of these, COVID-related Financial Hardship would have shared variance with (generic) financial difficulty. What remained in the model predicting higher symptom burden pointed particularly to the damaging effects of Financial Hardship. Indeed, Financial Hardship was associated with more than three times the risk of high versus low Long-COVID symptom burden.

Similarly, many COVID-specific stress factors that were bivariate predictors of Long COVID symptom burden in bivariate analyses were dropped from the multivariate model. One of the remaining factors, Risk-Taking, was associated with 1.72 times the risk of being in the high symptom-burden as compared to low, but it had no predictive impact for being in the middle symptom-burden group. This finding may reflect a more political aspect of social determinants of health, in that U.S. political party has been found to be predictive of whether or not one disregarded social-distancing recommendations of public health officials early in the pandemic and was also associated with higher mortality rate during COVID [49].

Social capital was also implicated in our analysis. This concept reflects how much potential an individual has for change in their “socio-location” at a given point in time [50]. It is pertinent to the impact of Long COVID because low social capital means the impact of Long COVID may be magnified [9]. In our multivariate model, COVID-related Worry was associated with 1.59 and 1.72 times the risk of middle and high symptom burden, respectively, as compared to low. This scale reflects the individual’s reported feelings of isolation, grumpiness, concern about further COVID infection, and being distracted by such concerns. Independent of Worry, having a strong social-support network had a protective effect against being in the high symptom-burden group, as compared to low, reducing this risk by about one third. However, there is also the possibility that those with higher Long COVID symptom burdens are feeling more worried and have less social support due to their illness, in part possibly due to stigma regarding Long COVID [34]. These individuals have more acutely experienced the negative impact of COVID directly and are justifiably concerned about further infection. In prior studies, Long COVID patients have expressed concerns about new limits on their social life as their health has changed and having their illness misunderstood or even dismissed by friends and family [32]. These experiences could understandably have adverse psychological impacts.

In contrast to other research, our study found that younger age, rather than older age, was associated with worse symptom burden. In our sample, the average age of the high symptom-burden group was about 52 whereas the low symptom-burden group had an average age of about 57. Thus, this contrast with past research may reflect a drilling down of age-related risk profiles in a relatively older sample. Alternatively, this finding may reflect the fact that younger people have different standards of comparison for what symptoms are “normal.” For example, unlike older individuals who might expect or habituate to feeling tired, the younger individuals might experience the same level of symptoms as more disruptive or unanticipated. This idea is similar to Rose et al.’s argument for why classifying individuals as having impaired health must account for age and gender norms [51].

Our multivariate findings echoed earlier studies that documented the heightened risk of having more comorbidities [12] as well as health/healthcare stress [52]. Of note, our entire sample reported large numbers of comorbidities (sample mean = 4.6, SD = 2.7), so that there was a restriction of range. Nevertheless, even in this narrow range, additional comorbidities were associated with higher Long COVID symptom burden. Further, several of the more prevalent comorbidities (e.g., arthritis, depression, insomnia) are also symptoms consistent with and perhaps exacerbated by Long COVID (see Supplemental Tables 3, 5).

Given the patterns noted in contrasting the bivariate and multivariate results, our findings suggest that many social determinants of health overlap considerably with Financial Hardship, Risk-Taking Behavior, Worry, and Social Support. We believe that these findings underscore the substantial role in symptom experience played by modifiable social and behavioral factors. Based on findings from earlier work on this same study sample [40], individuals reported notable changes in priorities and social norms over the course of the pandemic, all of which may have lasting effects on social support, and trust in public-health and political leadership.

These findings may also point to the importance of psychological mechanisms in Long COVID because psychological distress is a documented risk factor of Long COVID [53], and because intolerance of the current state of uncertainty regarding Long COVID may constitute a shared vulnerability factor for both psychological distress and persistent symptoms [30]. Further, psychological features may be critical in subtyping patients and symptoms and thus in identifying relevant biomarkers of Long COVID [30]. Finally, a better understanding of these underlying psychological mechanisms may help relieve patients [30].

Modifiable mechanisms could thus be the target of already validated therapeutic interventions [30]. Indeed, we believe that our findings suggest the need for multi-pronged support in the absence of a cure, such as symptom palliation, telehealth, social services, and psychosocial support. Is it possible, for example, that such multi-pronged support could both attenuate prominent symptoms such as fatigue and brain fog, while helping to rebuild the tenuous social fabric of communities that suffered so significantly due to COVID-related isolation. Regardless of the proposed therapeutic method, however, patients suffering from Long COVID should be included in rehabilitation programs to identify treatable physical, emotional, cognitive, and social traits [54]. Future research might focus on developing and testing such interventions using methods that build the intervention in collaboration with stakeholders, such as using a comprehensive dynamic trial model [55].

Limitations

The present study limitations should be noted. First, the attrition from baseline is notable and the causes for this attrition remain unknown. While it could be due to the usual reasons hindering survey research (e.g., lack of interest or time), it is also possible that it is due in part to COVID-related mortality because of the substantial numbers of such in the United States [56, 57], and because the study sample had a large number of chronic comorbidities, and people with chronic illness were particularly at risk of severe COVID and of COVID-related death [58, 59]. The selection bias analyses implicated only three characteristics in the attrition out of 16 considered, and two of these may reflect social determinants of health (more financial difficulties and lower education). The study sample is also less representative of non-white and/or Hispanic individuals, so the generalizability of study findings to these race/ethnicity groups is limited. Compared to those in the final follow-up sample who never reported having had COVID and thus were excluded from the present study, the analytic sample differed in 5 of 13 characteristics considered, the same two of which may reflect social determinants of health. They were also more likely to report two comorbidities that can be exacerbated by COVID (depression, asthma). A further limitation is that the alpha reliability of two of the COVID-specific factors was quite low (i.e., 0.29 and 0.15), which may have attenuated relationships with the dependent variable in the multivariate analyses [60]. Finally, the causal direction of the detected correlates of worse Long COVID symptom burden is unknown. For example, as noted above, social support had an OR consistent with a “protective effect,” but this same OR could be interpreted as simply reflecting that those with higher Long COVID symptom burdens feel less social support due to their illness. These relationships may also be bidirectional. The present findings might thus be considered hypothesis-generating to be tested in longitudinal data that tracks the emergence of Long COVID symptoms over time and what baseline and later factors lead to worse Long COVID symptom burden over time. Nonetheless, our findings demonstrate the co-occurrence of physical, psychological, and social challenges in the Long COVID experience.

Conclusions

Long-COVID symptom burden is associated with substantial, modifiable social and behavioral factors. Most notably, Financial Hardship was associated with more than three times the risk of high versus low Long-COVID symptom burden. These findings suggest the need for multi-pronged support in the absence of a cure, such as symptom palliation, telehealth, social services, and psychosocial support. Even if effective treatments for Long COVID symptoms are identified, socioeconomic and psychological sequelae of the pandemic would also need to be addressed.

Data availability

The study data are confidential and thus not able to be shared.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ES:

-

Effect size

- Long COVID:

-

Long-term post-acute effects of COVID-19

- LPA:

-

Latent profile analysis

- LRT:

-

Likelihood ratio test

- PROMIS:

-

Patient-Reported Outcome Information System

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved April 22, 2024, from https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 23, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

Soriano, J. B., Murthy, S., Marshall, J. C., Relan, P., & Diaz, J. V. (2022). A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. The Lancet Infectious Diseases., 22(4), e102–e107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030. Retrieved 22 April, 2024, from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). NCHHSTP Social Determinants of Health. Atlanta, GA. Retrieved 23 April, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/socialdeterminants/index.html#:w:text5Social%20determinants%20of%20health%20(SDOH,the%20conditions%20of%20daily%20life

Nalbandian, A., Desai, A. D., & Wan, E. Y. (2023). Post-COVID-19 condition. Annual Review of Medicine, 74, 55–64.

National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Research. (2024). Long COVID. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 22 April, 2024, from https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/long-covid

Fritsche, L. G., Jin, W., Admon, A. J., & Mukherjee, B. (2023). Characterizing and predicting post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection (PASC) in a large academic medical center in the US. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1328.

Voss, J. G., Pinto, M. D., & Burton, C. W. (2023). How do the social determinants of health impact the post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: A critical review. Nursing Clinics, 58(4), 541–568.

Sudre, C. H., Murray, B., Varsavsky, T., et al. (2021). Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nature Medicine., 27(4), 626–631.

Knight, D. R., Munipalli, B., Logvinov, I. I., Halkar, M. G., Mitri, G., & Hines, S. L. (2022). Perception, prevalence, and prediction of severe infection and post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 363(4), 295–304.

Kaushalya, L., Bowatte, G., Welikannage, K., & Yasaratne, D. (2022). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and predicting factors: A narrative review. Sri Lankan Journal of Health Sciences, 1(2), 36–47.

Azzam, A., & Khaled, H. (2023). Exploring the prevalence and factors associated with post-acute COVID syndrome in Egypt: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Egyptian Journal of Internal Medicine, 35(1), 67.

Cavaco, S., Sousa, G., Gonçalves, A., et al. (2023). Predictors of cognitive dysfunction one-year post COVID-19. Neuropsychology, 37(5), 557–567.

Arjun, M., Singh, A. K., Pal, D., et al. (2022). Characteristics and predictors of long COVID among diagnosed cases of COVID-19. PLoS ONE, 17(12), e0278825.

Munipalli, B., Ma, Y., Li, Z., et al. (2023). Risk factors for post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: Survey results from a tertiary care hospital. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 71(8), 896–906.

Schilling, C., Nieters, A., Schredl, M., et al. (2024). Pre-existing sleep problems as a predictor of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Journal of Sleep Research, 33(2), e13949.

Jacobs, E. T., Catalfamo, C. J., Colombo, P. M., et al. (2023). Pre-existing conditions associated with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Journal of Autoimmunity, 135, 102991.

Greißel, A., Schneider, A., Donnachie, E., Gerlach, R., Tauscher, M., & Hapfelmeier, A. (2024). Impact of pre-existing mental health diagnoses on development of post-COVID and related symptoms: A claims data-based cohort study. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 2408.

Yokoyama, T., & Gochuico, B. R. (2021). Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome pulmonary fibrosis: a rare inherited interstitial lung disease. European Respiratory Review, 30(159), 200193.

Poenaru, S., Abdallah, S. J., Corrales-Medina, V., & Cowan, J. (2021). COVID-19 and post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A narrative review. Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease, 8, 20499361211009384.

Kirchberger, I., Meisinger, C., Warm, T. D., Hyhlik-Dürr, A., Linseisen, J., & Goßlau, Y. (2024). Longitudinal course and predictors of health-related quality of life, mental health, and fatigue, in non-hospitalized individuals with or without post COVID-19 syndrome. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 22(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-024-02245-y

Lapin, B., Li, Y., Englund, K., & Katzan, I. L. (2024). Health-related quality of life for patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: Identification of symptom clusters and predictors of long-term outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 39, 1–9.

Hartung, T. J., Bahmer, T., Chaplinskaya-Sobol, I., et al. (2024). Predictors of non-recovery from fatigue and cognitive deficits after COVID-19: a prospective, longitudinal, population-based study. eClinical Medicine, 69, 102456.

Picascia, M., Cerami, C., Panzavolta, A., et al. (2023). Risk factors for post-COVID cognitive dysfunctions: The impact of psychosocial vulnerability. Neurological Sciences, 44(8), 2635–2642.

Gezici, A., & Ozay, O. (2020). How race and gender shape COVID-19 unemployment probability. University of Masssachusetts.

Moen, P., Pedtke, J. H., & Flood, S. (2020). Disparate disruptions: Intersectional COVID-19 employment effects by age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity. Work, Aging and Retirement, 6(4), 207–228.

Navar, A. M., Purinton, S. N., Hou, Q., Taylor, R. J., & Peterson, E. D. (2021). The impact of race and ethnicity on outcomes in 19,584 adults hospitalized with COVID-19. PLoS ONE, 16(7), e0254809.

Polyakova, M., Udalova, V., Kocks, G., Genadek, K., Finlay, K., & Finkelstein, A. N. (2021). Racial disparities in excess all-cause mortality during the early COVID-19 pandemic varied substantially across states: Study examines the geographic variation in excess all-cause mortality by race to better understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Affairs, 40(2), 307–316.

Lemogne, C., Gouraud, C., Pitron, V., & Ranque, B. (2023). Why the hypothesis of psychological mechanisms in long COVID is worth considering. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 165, 111135.

Tsai, J., Grace, A., Espinoza, R., & Kurian, A. (2023). Incidence of long COVID and associated psychosocial characteristics in a large US city. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37(5), 557–567.

Hossain, M. M., Das, J., Rahman, F., et al. (2023). Living with “long COVID”: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. PLoS ONE, 18(2), e0281884.

Bota, A. V., Bratosin, F., Bogdan, I., et al. (2024). Assessing the quality of life, coping strategies, anxiety and depression levels in patients with long-COVID-19 syndrome: A six-month follow-up study. Diseases, 12(1), 21.

Pantelic, M., Ziauddeen, N., Boyes, M., O’Hara, M. E., Hastie, C., & Alwan, N. A. (2022). The prevalence of stigma in a UK community survey of people with lived experience of long COVID. The Lancet, 400, S84.

COVID-19 BSSR Research Tools (NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR)). (2020).

Hays, R. D., Bjorner, J. B., Revicki, D. A., Spritzer, K. L., & Cella, D. (2009). Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of Life Research, 18, 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9

NeuroQOL. (2021). Quality of life in neurological disorders scoring manual, version 3.0.

Schwartz, C. E., Stucky, B. D., & Stark, R. B. (2021). Operationalizing the attitudes, behaviors, and perspectives of wellness: Development of a brief measure for use in resilience research. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 9(1), 1031–1052. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2021.2008940

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Schwartz, C. E., Borowiec, K., Waldman, A. H., et al. (2024). Emerging priorities and concerns in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: Qualitative and quantitative findings from a United States national survey. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1365657.

Shevlin, M., & Miles, J. N. (1998). Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(1), 85–90.

Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2009). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Vol. 718). Wiley.

Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (1989). Model-building strategies and methods for logistic regression. In D. W. Hosmer, S. Lemeshow, & R. X. Sturdivant (Eds.), Applied logistic regression (pp. 82–134). Wiley.

Wilson, I. B., & Cleary, P. D. (1995). Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA, 273(1), 59–65.

IBM. (2021). SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 28. IBM Corp.

Muthén, L.K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user's guide. Eighth ed. Cham: Muthén & Muthén.

Krieger, N., Testa, C., Chen, J. T., Hanage, W. P., & McGregor, A. J. (2022). Relationship of political ideology of US federal and state elected officials and key COVID pandemic outcomes following vaccine rollout to adults: April 2021–March 2022. The Lancet Regional Health-Americas, 16, 100384.

Moore, S., & Kawachi, I. (2017). Twenty years of social capital and health research: A glossary. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(5), 513–517.

Rose, M. S., Koshman, M. L., Spreng, S., & Sheldon, R. (1999). Statistical issues encountered in the comparison of health-related quality of life in diseased patients to published general population norms: Problems and solutions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology., 52(5), 405–412.

Ladds, E., Rushforth, A., Wieringa, S., et al. (2020). Persistent symptoms after Covid-19: Qualitative study of 114 “long Covid” patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 1–13.

Hirschtick, J. L., Titus, A. R., Slocum, E., et al. (2021). Population-based estimates of post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (PASC) prevalence and characteristics. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 73(11), 2055–2064. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab408

Gheorghita, R., Soldanescu, I., Lobiuc, A., et al. (2024). The knowns and unknowns of long COVID-19: From mechanisms to therapeutical approaches. Frontiers in Immunology, 15, 1344086.

Rapkin, B. D., & Trickett, E. J. (2005). Comprehensive dynamic trial designs for behavioral prevention research with communities: Overcoming inadequacies of the randomized controlled trial paradigm. In E. J. Trickett & W. Pequegnat (Eds.), Community interventions and AIDS (pp. 249–277). Oxford University Press.

Karmakar, M., Lantz, P. M., & Tipirneni, R. (2021). Association of social and demographic factors with COVID-19 incidence and death rates in the US. JAMA Network Open, 4(1), e2036462–e2036462.

Rossen, L. M., Nørgaard, S. K., Sutton, P. D., et al. (2022). Excess all-cause mortality in the USA and Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 and 2021. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 18559.

Hacker, K. A., Briss, P. A., Richardson, L., Wright, J., & Petersen, R. (2021). COVID-19 and chronic disease: The impact now and in the future. Preventing Chronic Disease, 18, 1–6.

Islam, N., Lacey, B., Shabnam, S., et al. (2021). Social inequality and the syndemic of chronic disease and COVID-19: County-level analysis in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 75(6), 496–500.

Nunnally, J. C. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill Education.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Wesley Michael, M.B.A., of Rare Patient Voice, LLC, and IPSOS-Insight, LLC, for facilitating access to participants; and to the participants themselves who provided data for this project.

Funding

C.E. Schwartz and K. Borowiec received research support from DeltaQuest Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CES and BDR designed the research study. CES and KB implemented data analysis. CES wrote the paper, and all authors edited the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest and report no disclosures.

Ethical approval

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the WCG Independent Review Board (#2021164).

Consent to participate

All participants provided informed consent prior to beginning the survey.

Consent for publication

All participants agreed to their data being published in a journal article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, C.E., Borowiec, K. & Rapkin, B.D. The faces of Long-COVID: interplay of symptom burden with socioeconomic, behavioral and healthcare factors. Qual Life Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03739-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03739-4