Abstract

Introduction

Several studies have shown that emotional competence (EC) impacts cancer adjustment via anxiety and depression symptoms. The objective was to test this model for the quality of life (QoL) of partners: first, the direct effect of partners’ EC on their QoL, anxiety and depression symptoms after cancer diagnosis (T1), after chemotherapy (T2) and after radiotherapy (T3); Second, the indirect effects of partners’ EC at T1 on their QoL at T2 and T3 through anxiety and depression symptoms.

Methods

192 partners of women with breast cancer completed a questionnaire at T1, T2 and T3 to assess their EC (PEC), anxiety and depression symptoms (HADS) and QoL (Partner-YW-BCI). Partial correlations and regression analyses were performed to test direct and indirect effects of EC on issues.

Results

EC at T1 predicted fewer anxiety and depression symptoms at each time and all dimensions of QoL, except for career management and financial difficulties. EC showed different significant indirect effects (i.e. via anxiety or depression symptoms) on all sub-dimensions of QoL, except for financial difficulties, according to the step of care pathway (T2 and T3). Anxiety and depression played a different role in the psychological processes that influence QoL.

Conclusion

Findings confirm the importance of taking emotional processes into account in the adjustment of partners, especially regarding their QoL and the support they may provide to patients. It, thus, seems important to integrate EC in future health models and psychosocial interventions focused on partners or caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer is a critical and stressful life event that can challenge people's views and shatter their core beliefs, which can in turn lead to traumatic psychological consequences for both patients and their caregivers (e.g. mental disorders, emotional distress) [1,2,3,4]. Emotional and cognitive processes are mobilized to assimilate this negative life event, reduce emotional distress, preserve quality of life (QoL), find meaning in such a situation and modify pre-diagnosis cognitive schemes in order to adjust to the disease and even report post-traumatic growth (i.e. overcoming a challenging life crisis and experiencing positive changes such as an increased appreciation for life and sense of personal strength, having more meaningful interpersonal relationships). The personal and social resources of people facing cancer are essential to develop these emotional and cognitive processes necessary to a better adjustment and a less impaired QoL.

Personal resources such as intrapersonal emotional competence (EC) seem to be essential, as they promote better health and well-being or QoL among the general and clinical population [5, 6]. Intrapersonal EC is associated with important variables in cancer adjustment such as fewer anxiety and depression symptoms, worries and intrusive thoughts related to cancer [7,8,9,10,11], better life satisfaction and QoL [9, 11, 12], stronger internal locus of control [13, 14] and resilience or post-traumatic growth [3, 15].

EC is part of the concept of emotional intelligence, which concerns inter-individual differences in the way to experience, attend to, identify, understand, regulate and use emotions. Emotional intelligence refers to a form of intelligence or ability (ability models) as well as a personality trait (trait models) [5, 16, 17]. Based on trait models, EC includes the tendency to identify, understand, express in an adapted manner, regulate and use emotions in daily life to maintain well-being and promote emotional and cognitive growth. Intrapersonal EC designates how individuals perceive their own emotion-related behaviours and abilities in daily life. Thanks to intrapersonal EC, individuals identify, understand and regulate their emotions for better health, adjustment to their environment and better QoL. Psychological interventions can improve EC and its beneficial effect on health, social relationships, resilience, QoL, or life satisfaction [18,19,20,21]. Indeed, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that interventions can improve EC and its associated factors (e.g. related to work, health, social relationships), with an effect that persists over time [19,20,21]. The emphasis should be on personalized training with an active and experiential approach, focused on specific EC with interactive groups [19, 21].

Baudry et al proposed a model revealing the significant effect of EC on anxiety and depression symptoms in cancer adjustment, especially in terms of QoL and supportive care needs [8, 9, 22, 23]. In daily life, EC helps reduce the psychological impact of disease diagnosis and treatments, thus, leading to better adjustment. As it reduces anxiety and depression symptoms, EC may help patients report a better QoL after surgery [9] or chemotherapy [22], as well as fewer unmet supportive care needs [8]. Interestingly, the effects of EC seem to be different according to the care pathway [22, 24]. Results showed that anxiety and depression evolve differently along the cancer care pathway and play a different role in the psychological processes that influence both QoL and supportive care needs [8, 22, 24]. Depression may be more present in the psychological processes influencing everyday life difficulties (i.e. management of children and everyday life), social relationships (e.g. support from close relatives or professionals) and couple relationships (e.g. couple cohesion, sexuality), while anxiety may be more present in the psychological processes influencing information and psychological needs or negative affectivity and apprehension about the future.

Emotional processes are essential for patients to cope with cancer-related difficulties. However, to our knowledge, no study has tested this model on caregivers, especially patients’ partners who often are the main caregivers in daily life. Indeed, partners also report a negative impact of cancer on their own health and QoL [25, 26]. Partners of young women with breast cancer report an impaired QoL [26] in terms of specific subjective experience related to their perception of the impact of the disease and treatments on their life context [27]. They report specific difficulties related to the support from or relationships with close relatives, financial strain, the daily management of children or negative affectivity and apprehension about the future [27,28,29]. As anxiety and depression symptoms may exacerbate their difficulties and reduce their QoL [26, 29,30,31], EC may protect partners from emotional distress and reduce these coping difficulties, thus, improving their QoL and the support they provide. It is important to better understand how cognitive-emotional processes can influence the QoL of partners at the various steps of the care pathway in order to promote better adjustment to these different stages.

The main objective of this study was to assess the involvement of emotional processes (i.e. impact of EC via anxiety and depression symptoms) in the QoL of partners of women with breast cancer. To our knowledge, this is the first study to address this specific issue in a longitudinal approach and for partners. The first objective was to assess the direct effect of partners’ EC at T1 on their QoL and on their anxiety and depression symptoms after cancer diagnosis (T1), after chemotherapy (T2) and after radiotherapy (T3). The second objective was to assess the indirect effects of partners’ EC at T1 on their QoL at T2 and T3 through anxiety and depression symptoms.

Methods

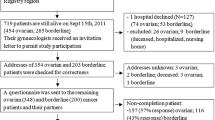

The present study is a first step in the analysis of partners’ data in the KALICOU-3 project and publication of findings. KALICOU-3 is a longitudinal, non-randomized, descriptive study carried out in collaboration with 30 cancer centres in France by the regional cancer centre of Lille. The main objective was to assess the effect of EC of young women with breast cancer and their partners on their QoL through their individual subjective experience of the disease throughout their care pathway, from chemotherapy to follow-up.

Participants and procedure

The sample was composed of 192 partners of women with breast cancer, who completed the self-reported questionnaire after diagnosis and within 3 weeks before chemotherapy (T1), and within 3 weeks after chemotherapy (i.e. after the 6th or 8th cycle of chemotherapy) ± targeted therapies (T2) and/or within 3 weeks after radiotherapy (T3). This phase took place between 2016 and 2020. All participants were male and living as a couple with a woman with breast cancer. Sample description is provided in Table 1.

The study complied with authorizations from the Ethics Committee (N° ID RCB: 2015-A01808-41; CPP: 03/005/2016) and the French regulation on clinical trials, and with the Declaration of Helsinki. Oncologists proposed the study to newly diagnosed women with non-metastatic breast cancer during a medical consultation. All participants (i.e. patients and partners) provided written informed consent.

Measures

Quality of life related to subjective experience of partners of young women with breast cancer: The French version of the Partners of Young Women Breast Cancer Inventory (Partner-YW-BCI) assesses the subjective experience of partners, i.e. their perception of the impact of cancer on their QoL in terms of daily difficulties and perceived repercussions of the disease and its treatments on different areas of life [27]. This scale is composed of 36 items on a five-point scale (1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”) and assesses eight sub-dimensions of the partners’ QoL (“at this moment, currently”) related to: (1) negative affectivity and apprehension about the future (α = 0.79 at T1 for the present study, six items, e.g. “I’m concerned about the future”, “I think about the disease every day”), (2) support from close relatives (α = 0.80, four items, e.g. “I talk about the disease with those around me”, “I can confide in some people”), (3) deterioration of relationships with close relatives (α = 0.74, five items, e.g. “I feel neglected by some of my close relatives”, “I can count on those around me”), (4) feeling of couple cohesion (α = 0.70, five items, e.g. “I feel that I support my partner”, “My couple is strong”), (5) body image and sexuality (α = 0.72, four items, e.g. “I no longer dare touch my partner physically”, “I feel less sexual desire”), (6) management of child(ren) and everyday life (α = 0.84, five items, e.g. “I have problems doing some domestic tasks”, “I have problems managing daily life with my child(ren)”), (7) career management (α = 0.73, three items, e.g. “I feel that I’m effective at work”, “I have problems doing my job”), and (8) financial difficulties (α = 0.71, four items, e.g. “I have problems dealing with the costs incurred by the disease”, “I have to reduce my lifestyle”). This scale helps identify daily problems coping with the partner’s disease (e.g. couple cohesion, social support). The scores were calculated from the mean of responses to the corresponding items. Higher scores indicate a poorer QoL or subjective experience (i.e. greater difficulties and repercussions of the disease and its treatments on life).

Emotional competence: The French version of the Profile of Emotional Competence (PEC) assesses the participants’ perception of their intrapersonal EC (i.e. about ones’ own emotions) used in daily life [16]. This scale provides a score of intrapersonal EC with 25 items (α = 0.73, e.g. “I find it difficult to handle my emotions”, “When I am touched by something, I immediately know what I feel”) and a five-point scale (1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”). The score was calculated from the mean of responses to the corresponding items. A higher score indicates a higher use of EC in daily life.

Anxiety and depression: The French version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) assesses anxiety and depression symptoms [32], based on 14 items on a four-point scale. This scale provides a score of anxiety symptoms (α = 0.74, seven items) and one of depression symptoms (α = 0.76, seven items). The scores were calculated from the sum of responses to the corresponding items. Higher scores indicate stronger anxiety or depression symptoms.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0. Partial correlations were used to test the first objective of the study: the direct effect of intrapersonal EC at T1 (i.e. after diagnosis and before chemotherapy) on the sub-dimensions of QoL, anxiety and depression symptoms of partners at T1, T2 (i.e. after chemotherapy ± targeted therapies), and T3 (i.e. after radiotherapy).

Regressions were used to test the second objective of the study: to test the indirect effect of EC at T1 on sub-dimensions of QoL at T2 and T3 through anxiety and depression symptoms, using the Macro PROCESS [33]. It assesses whether a variable X (i.e. EC at T1) influences variables M (i.e. anxiety and depression at T2 and T3) that, in turn, influence a variable Y (i.e. QoL at T2 and T3), without necessarily having a direct effect of X on Y [34, 35]. PROCESS serves to quantify indirect effects using a bootstrapping procedure with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Eight models (i.e. for the eight sub-dimensions of QoL) at T2 and eight models at T3 were, thus, tested (see, Fig. 1).

Model used to test indirect effect of intrapersonal EC at T1 (after diagnosis) on quality of life related to subjective experience of partners at T2 (after chemotherapy) and T3 (after radiotherapy) via anxiety and depression symptoms at T2 or T3. Note. c’ = total indirect effect of intrapersonal EC on subjective experience through anxiety and depression symptoms; c1’ = specific indirect effect of intrapersonal EC on subjective experience through anxiety; c2’ = specific indirect effect of intrapersonal EC on subjective experience through depression

All models at T1 were adjusted for age, education level, and the delay between diagnosis and T1. All models at T2 were adjusted for age, education level, and the delay between diagnosis and T2. Finally, all models at T3 were adjusted for age, education level, and the delay between diagnosis and T3.

Results

Sample description

Analyses were based on 192 male partners of women with non-metastatic breast cancer without antecedents. They were 25 to 60 years old and most of them were active at inclusion (Table 1). The scores for sub-dimensions of QoL, EC and anxiety and depression symptoms are described and presented in the supplemental material (Table S1).

Direct effects of EC (Objective 1)

Overall, partners who use their EC after diagnosis more showed fewer anxiety and depression symptoms and better QoL (i.e. significant effect for all sub-dimensions of QoL, except for career management at T1 and T2, body image and sexuality at T2, and financial difficulties) at all stages of the care pathway (Table 2).

Indirect effects of EC (Objective 2)

After controlling for age, education level and the delay between diagnosis and questionnaire completion, EC showed a significant indirect effect via anxiety and/or depression symptoms on all sub-dimensions of QoL at T2 and T3, except for support from close relatives and financial difficulties only at T3 (Table 3).

Results revealed that the mediational role of anxiety and depression varied according to the dimensions and times. Anxiety was a better mediational variable for psychological and individual dimensions (i.e. negative affectivity and apprehension about the future) at T2 and T3, while depression was a better mediational variable for personal difficulties involving relatives (e.g. deterioration of relationships, couple cohesion, body image and sexuality) and financial/professional domain (i.e. career management, finances at T2). Anxiety and depression were together significant mediators for practical tasks related to the adaptation of family roles at home (i.e. management of children and everyday life) at T2 and T3. Results revealed a particular result for support from close relatives at T2: the indirect effect of EC was positive via anxiety but negative via depression. Thus, the less partners reported using EC in everyday life after diagnosis, the more they reported anxiety at T2 and, in consequence, the less they reported difficulties related to support from close relatives.

The significant indirect effects varied according to the stage of the care pathway. For instance, the effect of EC on the deterioration of relationships showed mainly via depression at T2 and via anxiety and depression at T3, and inversely for body image and sexuality. Significant indirect effects were found for support from close relatives and finances only at T2.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to assess the indirect effects of EC of partners of women with breast cancer after diagnosis (T1) on their QoL after chemotherapy (T2) and radiotherapy (T3) through anxiety and depression symptoms. Overall, EC predicted better QoL (i.e. fewer difficulties in daily life) and fewer anxiety and depression symptoms at T1, T2 and T3. However, no significant effect was found for difficulties related to finances at all times and for career management at T1 and T2. The present study, thus, highlights the involvement of emotional processes in the QoL of partners and various significant indirect effects (i.e. via anxiety or depression symptoms) of EC according to the different stages of the care pathway (T2 and T3).

Overall, results showed a significant direct impact of EC on all dimensions of QoL of partners, except for career management and financial difficulties. These results are in line with those observed on women with breast cancer [22]: EC appears as a more significant resource for partners’ than for women’s QoL, except for the career and financial domains that were little or not influenced by EC for both patients and partners. Career management and financial difficulties may be more related to variables other than emotional and psychological resources such as EC. More material variables require other adjustments on which emotional variables seem to have little influence. Caregivers experience impacts on their work (e.g. withdrawal from the labour market, work modifications, absenteeism, loss of productivity at work) due to the difficulty of balancing work and caregiving responsibilities [36]. This difficulty can be exacerbated by partner status (e.g. primary caregiver, level of burden) and employment-related factors (e.g. flexibility in work hours, workplace accommodations, employment sector, communication with employer).

Regardless of the stage of the care pathway, the more partners reported using EC in everyday life after diagnosis, the less they reported anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as everyday difficulties (i.e. related to negative affectivity and apprehension about the future, support from close relatives, deterioration of relationships with close relatives, feeling of couple cohesion, body image and sexuality, management of children and everyday life). These results show the importance of identifying partners who may have limited use of their EC in daily life, from the very beginning of the cancer care pathway. A consultation with a psychologist could be offered to reinforce these EC in order to limit the development of emotional, social and practical difficulties during treatment.

EC did not predict difficulties related to body image and sexuality after chemotherapy phase (T2). This suggests that variables other than personal resources, such as treatments and their negative repercussions as well as associated patient experience, may further influence this variable. Women's physical appearance, self-esteem and communication within the couple may have a significant influence regarding the impact of cancer on relationships [37]. Caregiving burden, marital satisfaction and lower threat appraisals may be also crucial in the sexual QoL of partners [38]. A systematic review of the literature shows the importance of focusing on relationship dynamics, dyadic coping and supporting couple cohesion [37]. Including the couple as a unit in clinical consultations may help preserve its functioning and facilitate both patients’ and partners’ adjustment. Finally, dyadic analyses should, thus, be helpful to better understand the determinants of partners’ QoL and couples’ well-being. In fact, the experience of patients and that of partners seem to be interdependent [30, 31, 39].

One of the major results is the significant effect of EC on anxiety and depression symptoms at all three stages of the care pathway. This supports previous findings showing a significant effect of EC on emotional distress in both general and clinical populations [5, 6] and in cancer patients [7,8,9, 22, 40,41,42]. As patients and partners tend to better identify, understand and regulate their emotions, they are able to better manage the emotional impact of diagnosis and treatments, thus, protecting them from anxiety and depressive symptoms throughout the care pathway. These findings also support previous research showing a central/indirect effect of EC on emotional distress in cancer adjustment and QoL [8, 9, 22, 23] at various stages of the care pathway. It is, therefore, crucial to understand how psychological processes can impact difficulties related to the disease in everyday life. These results support the predictive role of emotional distress in partners' QoL [26, 29,30,31], with the idea that EC could be a resource reducing anxiety and depression symptoms at various stages of the care pathway to ultimately promote a less impaired QoL. This appears to be particularly important in light of the increased difficulties and deterioration of the QoL of partners over time (see supplemental material).

The psychological processes involved in the dimensions of QoL related to the specific subjective experience of partners seem different according to the stage of the care pathway and the anxiety or depression symptoms, as previously highlighted in cancer patients [8, 9, 22, 24]. It appears that anxiety plays a more important mediational role than depression in psychological and individual dimensions (i.e. negative affectivity and apprehension about the future) as well as a significant involvement in practical tasks related to the adaptation of family roles at home (i.e. management of children and everyday life). The overall anxiety of partners may, thus, be partly responsible for the burden they feel when managing their new roles in daily life. When using their EC, they report fewer anxiety symptoms and feel more confident managing their personal life and future. Surprisingly, the indirect effect of EC via anxiety on support from close relatives was positive at T2. Thus, the more partners reported using EC in everyday life after diagnosis, the less they reported anxiety at T2 and, in consequence, the more they reported difficulties related to support from close relatives. Partners’ anxiety may draw attention to themselves and help them get more support from relatives, unlike depression. More anxious partners may report different expectations and support needs than more depressed partners. In contrast, depression plays a more important role in dimensions involving interpersonal relationships (i.e. support from close relatives, couple cohesion, body image and sexuality) and career/financial management. Depressive symptoms can generate more difficulties in seeking the help of others and opening up to others, with self-withdrawal and a loss of vital energy. These processes have also been identified in women with breast cancer (regarding negative affectivity and apprehension about the future, support from close relatives and couple cohesion) [22], showing that they may be common to both patients and partners. Exploring emotional processes (involving EC, anxious and depressive symptoms) may, therefore, provide insight into the emotional, social and practical difficulties reported by patients and partners.

These results show the importance of distinguishing between anxious and depressive symptoms, which could be involved in different processes and, therefore, have a different impact on both partners' and patients’ experience. This should be considered in the psychological management and assessment of emotional distress in clinical routines. Future studies should expand on these findings using more precise tools to evaluate anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as potential mediators or moderators (e.g. ruminations, caregiver burden, hope, couple satisfaction) to better understand the processes involved. A qualitative study could help assess how EC is used in daily life at each step of the care pathway and how it may impact the lives of partners and patients and their dyadic coping. Further analysis on the deterioration of partners’ QoL at various steps of the care pathway could provide an important insight into the present findings.

Health professionals should pay more attention to psychological temporality and involve psychologists into the care pathway. Assessing EC, anxiety and depression symptoms in women with breast cancer and their partners after diagnosis should help identify those who are most at risk of difficulties and may, therefore, require particular psychological support. These findings provide guidance to psychologists on the value of targeting EC and anxiety/depression in psychosocial interventions for patients, caregivers and couples. Supporting patients and partners elaboration of their emotional experience and improving their EC (e.g. identification, understanding, expression and regulation) should help reduce their anxious and depressive symptoms and improve their QoL. This study confirms the importance of developing and offering specific supportive care to partners and all natural caregivers. Interventions based on interpersonal counselling (e.g. focused on mood and affect management, emotional expression, interpersonal communication and relationships, psycho-education) and supportive health education (e.g. to improve the active role of partners in cancer adjustment) have shown beneficial effects on anxiety, depression and QoL of patient–caregiver dyads [43].

Limitations

The present study has limitations such as a limited generalization to all caregivers of cancer patients, as this sample was composed exclusively of partners of young women with non-metastatic breast cancer. These results will need to be supported by further studies and other types of analysis (mixed models). Sociodemographic and psychological variables (e.g. financial status, caregiver tasks, perceived burden, psychiatric history) could have improved the understanding of the results. Future research could take these variables into account in order to evaluate the impact of social, territorial or psychological inequalities among these couples.

Conclusion

Findings support the major impact of EC on emotional distress at different steps of the care pathway (e.g. diagnosis, chemotherapy, radiotherapy) for partners of women with breast cancer. It seems essential to consider emotional processes (i.e. impact of EC via emotional distress) in the experience of partners and patients to offer them optimal psychological support based on emotional elaboration and the reinforcement of EC for better management of their anxiety and depression symptoms. This should help partners to improve their perception of daily life, limit the impact on their QoL and probably improve the support they provide to patients. Health care policies should develop further means to provide specific supportive care to caregivers (e.g. dedicated consultations and professionals, supportive care day hospital, specific interventions). Finally, it seems important to better integrate EC and emotional distress in future QoL and health models, and in psychosocial interventions.

References

Harvey, J., & Berndt, M. (2020). Cancer caregiver reports of post-traumatic growth following spousal hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Anxiety Stress & Coping. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1845432

Park, C. L. (2013). The meaning making model: A framework for understanding meaning, spirituality, and stress-related growth in health psychology. The European Health Psychologist, 15(2), 40–47.

Rider Mundey, K., Nicholas, D., Kruczek, T., Tschopp, M., & Bolin, J. (2019). Posttraumatic growth following cancer: The influence of emotional intelligence, management of intrusive rumination, and goal disengagement as mediated by deliberate rumination. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 37(4), 456–477.

Tedeschi, R., & Calhoun, L. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 1–18.

Baudry, A.-S., Grynberg, D., Dassonneville, C., Lelorain, S., & Christophe, V. (2018). Sub-dimensions of trait emotional intelligence and health: A critical and systematic review of the literature. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59(2), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12424

Sánchez-Álvarez, N., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2016). The relation between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic investigation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1058968

Amirifard, N., Payandeh, M., Aeinfar, M., Sadeghi, M., Sadeghi, E., & Ghafarpo, S. (2017). A survey on the relationship between emotional intelligence and level of depression and anxiety among women with breast cancer. International Journal of Hematology-Oncology & Stem Cell Research, 11(1), 54–57.

Baudry, A.-S., Lelorain, S., Mahieuxe, M., & Christophe, V. (2018). Impact of emotional competence on supportive care needs, anxiety and depression symptoms of cancer patients: A multiple mediation model. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(1), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3838-x

Baudry, A. S., Anota, A., Mariette, C., Bonnetain, F., Renaud, F., Piessen, G., et al. (2019). The role of trait emotional intelligence in quality of life, anxiety and depression symptoms after surgery for esophageal or gastric cancer: A French national database FREGAT. Psycho Oncology, 28(4), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5023

Guil, R., Morales-Sánchez, L., Ruiz-González, P., Gomez-Molinero, R., & Gil-Olarte Márquez, P. (2022). The key role of emotional repair and emotional clarity on depression among breast cancer survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 4652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084652

Megías, J., Romero, Y., Ojeda, B., Peña-Jurado, I., & Gutierrez-Pastor, P. (2019). Belief in a just world and emotional intelligence in subjective well-being of cancer patients. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2019.28

Teques, A. P., Carrera, G. B., Ribeiro, J. P., Teques, P., & Ramón, G. L. (2016). The importance of emotional intelligence and meaning in life in psycho-oncology. Psycho-Oncology, 25(3), 324–331.

Brown, R. F., & Schutte, N. S. (2006). Direct and indirect relationships between emotional intelligence and subjective fatigue in university students. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(6), 585–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.05.001

Naz, R., Kamal, A., & Mahmood, A. (2016). Relationship of emotional intelligence and health locus of control among female breast cancer patients in pakistan. Pakistan Armed Forces Medical Journal, 66(6), 903–908.

Guil, R., Ruiz-González, P., Morales-Sánchez, L., Gómez-Molinero, R., & Gil-Olarte, P. (2022). Idiosyncratic profile of perceived emotional intelligence and post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: findings of a multiple mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148592

Brasseur, S., Grégoire, J., Bourdu, R., & Mikolajczak, M. (2013). The Profile of Emotional Competence (PEC): Development and validation of a self-reported measure that fits dimensions of emotional competence theory. PLoS ONE, 8(5), e62635–e62635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062635

Mikolajczak, M. (2009). Going beyond the ability-trait debate: The three-level model of emotional intelligence. E-Journal of Applied Psychology, 5(2), 25–31.

Delhom, I., Satorres, E., & Melendez, J. (2020). Can we improve emotional skills in older adults? Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction, and resilience. Psychosocial Intervention. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a8

Hodzic, S., Scharfen, J., Ripoll, P., Holling, H., & Zenasni, F. (2017). How efficient are emotional intelligence trainings: A meta-analysis. Emotion Review, 10(2), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073917708613

Kotsou, I., Mikolajczak, M., Heeren, A., Grégoire, J., & Leys, C. (2018). Improving emotional intelligence: A systematic review of existing work and future challenges. Emotion Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073917735902

Mattingly, V., & Kraiger, K. (2019). Can emotional intelligence be trained? A meta-analytical investigation. Advancing Training for the 21st century, 29(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.03.002

Baudry, A.-S., Yakimova, S., Congard, A., Untas, A., Guiu, S., Lefeuvre-Plesse, C., et al. (2022). Adjustment of young women with breast cancer after chemotherapy: A mediation model of emotional competence via emotional distress. Psycho-Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5876

Zysberg, L. (2018). Emotional intelligence and health outcomes. Psychology, 9(11), 2471–2481.

Baudry, A.-S., Gehenne, L., Grynberg, D., Lelorain, S., Piessen, G., & Christophe, V. (2021). Is the Postsurgical Quality of Life of Patients With Esophageal or Gastric Cancer Influenced by Emotional Competence and Neoadjuvant Treatments? Cancer Nursing, Publish. Consulté à l’adresse https://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/Fulltext/9000/Is_the_Postsurgical_Quality_of_Life_of_Patients.98850.aspx

Yıldız, G., & Hiçdurmaz, D. (2019). An overlooked group in the psychosocial care in breast cancer: Spouses. Meme Kanserinin Psikososyal Bakımında Gözden Kaçırılan Kısım: Eşler., 11(2), 239–247.

Cohee, A. A., Bigatti, S. M., Shields, C. G., Johns, S. A., Stump, T., Monahan, P. O., & Champion, V. L. (2018). Quality of life in partners of young and old breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 41(6), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000556

Christophe, V., Duprez, C., Congard, A., Fournier, E., Lesur, A., Antoine, P., & Vanlemmens, L. (2015). Evaluate the subjective experience of the disease and its treatment in the partners of young women with non-metastatic breast cancer. European Journal Of Cancer Care, 37(1), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12327

Congard, A., Christophe, V., Duprez, C., Baudry, A.-S., Antoine, P., Lesur, A., et al. (2019). The self-reported perceptions of the repercussions of the disease and its treatments on daily life for young women with breast cancer and their partners. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 37(1), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1479326

Borstelmann, N. A., Gray, T. F., Gelber, S., Rosenberg, S., Zheng, Y., Meyer, M., et al. (2022). Psychosocial issues and quality of life of parenting partners of young women with breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 30(5), 4265–4274.

Duprez, C., Vanlemmens, L., Untas, A., Antoine, P., Lesur, A., Loustalot, C., et al. (2017). Emotional distress and subjective impact of the disease in young women with breast cancer and their spouses. Future Oncology. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2017-0264

Li, Q., Lin, Y., Xu, Y., & Zhou, H. (2018). The impact of depression and anxiety on quality of life in Chinese cancer patient-family caregiver dyads, a cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1051-3

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

Memon, M., Hwa, C., Ramayah, T., Ting, H., & Chuah, F. (2018). Mediation analysis: Issues and recommendations. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 2(1), i–ix.

Xiang, E., Guzman, P., Mims, M., & Badr, H. (2022). Balancing work and cancer care: Challenges faced by employed informal caregivers. Cancers. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14174146

Valente, M., Chirico, I., Ottoboni, G., & Chattat, R. (2021). Relationship dynamics among couples dealing with breast cancer: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 7288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147288

Yeung, N. C. Y., Zhang, Y., Ji, L., Lu, G., & Lu, Q. (2019). Correlates of sexual quality of life among husbands of Chinese breast cancer survivors. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 40, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.03.007

Parmelee Streck, B., & LoBiondo-Wood, G. (2020). A systematic review of dyadic studies examining depression in couples facing breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2020.1734894

Schmidt, J. E., & Andrykowski, M. A. (2004). The role of social and dispositional variables associated with emotional processing in adjustment to breast cancer: An internet-based study (English). Health Psychology (Hillsdale, N.J.), 23(3), 259–266.

Smith, S., Petrides, K. V., Green, J., & Sevdalis, N. (2012). The role of trait emotional intelligence in the diagnostic cancer pathway. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(11), 2933–2939.

Smith, S., Turner, B., Pati, J., Petrides, K., Sevdalis, N., & Green, J. (2012). Psychological impairment in patients urgently referred for prostate and bladder cancer investigations: The role of trait emotional intelligence and perceived social support. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(4), 699–704.

Badger, T. A., Segrin, C., Sikorskii, A., Pasvogel, A., Weihs, K., Lopez, A. M., & Chalasani, P. (2020). Randomized controlled trial of supportive care interventions to manage psychological distress and symptoms in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. Psychology & Health, 35(1), 87–106.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French National Cancer Institute (INCa) and received a grant from a Contrat de Plan Etat-Région CPER Cancer 2015-2020. We thank all participants of the KALICOU-3 study, all the investigators (especially the main investigators: Dr Christine Abraham, Patrick Bouchaert, Nadine Dohollou, Aurélie Fadin, Isabelle Gabelle-Flandrin, Laurent Gilbeau, Claire Giraud, Cécile Guillemet, Anne-Claire Hardy-Bessard, Catherine Loustalot, Roxana Pristavu, Karine Prulhiere, Gaetan de Rauglaudre, Hassan Rhliouch, Olivier Romano, Aude-Marie Savoye, Sophie Vautier-Rit, Hélène Vegas), Clinical Research Associates, Emilie Decoupigny, Sara Diomande, Marie Vanseymortier, Caroline Decamps, Fanny Ben Oune, and Emilie Cooke-Martageix for English proofreading. The Northwest Data Center (CTD-CNO) are acknowledged for managing the data. It is supported by grants from the French National League Against Cancer (LNC) and the French National Cancer Institute (INCa).

Funding

This work was supported by the French National Cancer Institute (INCa).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ASB, LV, AC, AU, and VC contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by LV, CSD, CLP, FC, SG, JSF, and BS. Material preparation and analysis of data were performed by ASB and SY. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ASB and VC, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with authorizations from the Ethics Committee (N° ID RCB: 2015-A01808-41; CPP: 03/005/2016).

Consent to participation

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publication

The manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form (including any individual details, images or videos).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Baudry, AS., Vanlemmens, L., Congard, A. et al. Emotional processes in partners’ quality of life at various stages of breast cancer pathway: a longitudinal study. Qual Life Res 32, 1085–1094 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03298-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03298-6