Abstract

Introduction

HRQOL in transplant candidates and recipients who are also infected with HIV and are awaiting a kidney, or have received one from a HIV-positive donor, has not been previously investigated.

Methods

The HRQOL of 47 HIV-positive kidney transplant candidates and 21 recipients from HIV-positive donors was evaluated using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) and face to face interviews at baseline and at 6 months. The correlation between SF-36 scores and sociodemographic, clinical and nutritional factors was determined.

Results

68 patients completed the SF-36 at baseline and 6 months. Transplant candidates: transplant candidates had lower HRQOL than recipients. The main mental stressors were income, employment and waiting for a donor. Physical health complaints were body pain (BP) and fatigue. Pre-albumin and BMI was positively correlated with general health at baseline (r = 0.401, p = 0.031 and r = 0.338, p = 0.025). Besides a positive association with role physical (RP) and BP, albumin was associated with overall physical composite score (PCS) (r = 0.329, p = 0.024) at 6 months. Transplant recipients: Transplant recipients had high HRQOL scores in all domains. PCS was 53.8 ± 10.0 and 56.6 ± 6.5 at baseline and 6 months respectively. MCS was 51.3 ± 11.5 and 54.2 ± 8.5 at baseline and 6 months respectively. Albumin correlated positively with PCS (r = 0.464, p = 0.034) at 6 months and role emotional (RE) (r = 0.492, p = 0.024). Higher pre-albumin was associated with better RE and RP abilities and MCS (r = 0.495, p = 0.034). MAMC was associated with four domains of physical health and strongly correlated with PCS (r = 0.821, p = 0.000).

Conclusion

Strategies to improve HRQOL include ongoing social support, assistance with employment issues and optimising nutritional status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was formerly a contraindication for kidney transplantation until outcomes similar to transplant recipients in the general population were observed [1, 2]. Initially, HIV-negative donors were used [3] for fear of an emergent super-infection, drug resistance and hastened progression to AIDS, should positive donors be used [4].

In 2008, however, South Africa (SA) became the first country to successfully transplant HIV-positive patients with donor kidneys from HIV-positive individuals, improving prognosis in patients, who would have demised within months. By all objective measures, the surgery was successful, and HIV parameters showed no evidence of hastened HIV disease progression post-transplantation [4], paving the way for many more transplants in SA and globally.

The literature that followed focussed primarily on clinical markers and pharmacotherapeutic strategies to extend survival, with little mention about the quality of life these additional years afford. Yet, HRQOL assessments would be an adjunct to clinical practice providing insight into psychosocial factors affecting health, appraise their current health care, and aid decision-making in improving all aspects of a patient’s life [5]. In this way, clinical care and assessments are more patient, rather than disease focussed [6]. This would be especially relevant in this patient group, as the usual impact of chronic disease on their everyday personal and social contexts, would likely be augmented, in the presence of two major conditions [6].

It is well-known that dialysis adversely affects HRQOL with notable improvements observed post-transplantation [7]. However, studies also indicate that post-transplant HRQOL is related to clinical outcomes and that low quality of life (QOL) scores in the physical component of HRQOL is predictive of lower graft and patient survival in transplant recipients [8]. Hence, a need to identify and optimise factors that affect HRQOL.

Within this context, the aim of the current study was to describe the HRQOL of HIV-positive kidney transplant candidates and recipients from HIV-positive donors, and to determine the relationship between clinical, nutritional status and sociodemographic factors associated with HRQOL.

Methods

Participants

The national HIV “positive-to-positive” kidney transplant programme has candidates and recipients residing across SA; however, it is managed from a single centre—Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH) in Cape Town. Potential candidates receiving dialysis in their home province, travel to GSH when a donor becomes available, returning home post-transplantation. Figure 1 illustrates the patient enrolment process from 92 prospective participants listed at GSH (68 transplant candidates, 24 transplant recipients), who were contacted telephonically or during their outpatient visit, with an invitation to participate. More than 80% (= 76) of those who were invited, agreed to participate and were subsequently assigned to two categories namely (i) HIV-positive transplant recipients who received a kidney from a HIV-positive donor; and (ii) HIV-positive transplant candidates on the waiting list to receive a kidney from a HIV-positive donor. Written informed consent was obtained from all 76; however, only 68 completed the HRQOL questionnaire at both time points, constituting this study’s sample. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) (Approval number BE 327/13).

Health-related quality of life

Questionnaire

An interviewer-administered Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2 [9] assessed QOL in the past month. It is the most commonly used generic measurement of QOL in renal replacement therapy [10]. A generic tool was considered most appropriate for this study as using an end stage renal disease (ESRD)-specific measure might exclude questions specifically relevant to HIV, and would limit comparison of this study’s data to renal populations only. A generic measure allowed comparison of this study’s data with HIV and ESRD populations.

The 36 items that categorise eight domains of health [11], are briefly described in Table 1 [12, 13].

The SF-36 software uses a scoring algorithm to translate the raw data into scores for each domain. This ranges from zero (worst health) to 100 (best possible health) [14, 15]. Therefore, higher scores reflect better daily functioning and well-being [11]. The eight domains are further merged into two composite scores, namely the physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS).

The average PCS and MCS for the general population are 50 [16]. Therefore, scores above or below 50 suggest better or worse perceived mental or physical health respectively. A decrease in PCS indicates adverse effects in the domains of physical health namely worse body pain (BP), vitality and fatigue, as well as limitations in physical, social and self-care roles and activities. A decreasing MCS shows higher levels of mental stress and greater limitations in social and functional activities due to emotional stress [17].

The validity of the SF-36 has been demonstrated across nationalities and types of renal replacement therapies [15, 18]. In the transplant population specifically, it was found to be reliable, valid, discriminant and responsive [15, 19].

Interviews

Face-to-face semi-structured interviews generated narratives on life experiences. Interviews used a scope of inquiry developed for the purpose of the study, with input from a clinical psychologist. Questions were literature-based issues relevant to renal patients. The interview guide was scripted to enhance reproducibility, but was not an inflexible tool [20], allowing expression of other thoughts and feelings as they arose. Participants were unwilling to be audio-recorded; therefore all narratives were manually recorded.

Nutritional assessment

Anthropometry

Dietitians conducted anthropometric assessments following refresher training and a post-training test to standardise measurement technique. Weight (WT), height (Ht), triceps skinfold thickness (TSF) and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) were obtained using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) protocol [21]. Height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured using equipment at outpatient and dialysis centres. Post-dialysis (dry weights) were recorded, and TSF and MUAC measurements on the non-access arm [22, 23]. MUAC (cm) and TSF in millimetres (mm) were measured using a Slim Guide calliper (USA) and a SECA 201 measuring non-stretch tape (Germany). A mean of three readings were recorded. BMI (kg/m2) was classified according to the World Health Organization BMI categories: underweight (≤ 18.5), normal weight (18.5 to 24.9), overweight (25.0 to 29.9), obese class I (30.0 to 34.9), obese class II (35.0 to 39.9) and obese class III (≥ 40) [24]. Mid arm muscle circumference (MAMC) was used a proxy measure of muscle mass, calculated using the following equation [25]:

Blood biomarkers

Hypoalbuminemia was determined at < 38 g/l for hypoalbuminemia [26]. Pre-albumin was a marker of malnutrition, based on good agreement, sensitivity and specificity when compared to detailed nutritional assessments [27]. A cut-off of < 30 mg/l was set as a criterion for low pre-albumin [26].

Pilot study

To ensure an adequate sample size was available for the main study, HIV-negative patients were used for the pilot. This was deemed suitable for the purpose of the pilot, which was to test the logistics around data collection, as well as understanding and comprehension of the questionnaires. Therefore, the interview schedule, sociodemographic and SF-36 questionnaires were tested for face validity, to eliminate ambiguity and for ease of administration [28, 29] on 12 HIV-negative transplant candidates (8) and recipients (4). These patients were not included in the study sample.

Data analysis

Questionnaire

Quality Metric Health Outcomes™ Scoring Software 4.0 generated the eight domain scores and two component summary scores. The mean SF-36 scores were calculated per domain. Data was analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) version 25.0. Means and standard deviation were calculated for all continuous variables, while frequency distributions and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Differences between group means were compared at baseline and 6 months using the independent samples t test. Paired samples t test was used to calculate the change in HRQOL by calculating the difference in mean scores of each domain from baseline to 6 months. ANOVA (or independent samples t test) was applied to test for significant differences in the measured SF-36 domains across demographic categories. Pearson’s correlation determined the relationship between HRQOL and nutritional status (MAMC values), as well as continuous variables. A p value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The questionnaire items were tested for consistency and validity. Cronbach’s alpha was used to test the scale reliability.

Interview analysis

Interview scripts were manually coded and categorised to extract themes [20] by the primary researcher, followed by an independent experienced coder. Any coding inconsistencies were discussed and reconciled. Categories were merged into themes that most succinctly captured the thoughts, feelings and attitudes of participants [30], and reported within the framework of the SF-36 domains.

Results

Participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

68 participants completed the HRQOL assessments at baseline and 6 months. The outstanding eight showed no differences in the sociodemographic or clinical characteristics with the 68 participants.

Table 2 presents the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample. There were significantly more diabetics 14/68 (20.6%) among transplant candidates compared to the one transplant recipient (p = 0.049).

Participant nutritional characteristics

Table 3 indicates that at baseline, a significant number of the transplant recipients had low pre-albumin (< 30 mg/l), χ2 (1) = 6.850, p = 0.009. At baseline, significantly more transplant recipients than candidates than had normal serum albumin, χ2 (1) = 14.592, p < 0.0005. There were no other significant differences between the two groups.

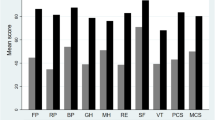

HRQOL—SF-36

SF-36 demonstrated suitability as a measure of HRQOL in reliability and validity tests prior to analysis (not included). SF-36 scores were separated by treatment modality at both baseline and 6 months (Figs. 2, 3). Table 4 indicates these domain scores with significant differences and the two composite scores (PCS and MCS). At 6 months, the GH domain had the largest significant difference in domain scores between candidates and recipients (d = 4.352, p = 0.000). For the physical and mental composite scores, differences between the two groups were significant for PCS only at baseline and 6 months (df = 2.708, p = 0.009 and df = 4.464, p = 0.000).

Correlations of HRQOL with sociodemographic, nutritional status and clinical variables

The association between HRQOL and albumin (Table 5) was demonstrated in both candidates and recipients in the overall PCS at the 6-month assessment, but not the MCS. For the candidates, there was a significant association with low albumin levels and low HRQOL scores in the physical domains of RP (r = 0.304, p = 0.038) and BP (r = 0.358, p = 0.014). This finding illustrated that candidates with lower albumin levels experienced more limitations in daily activities and were in more pain. In recipients, lower scores in the physical domains of PF (r = 0.514, p = 0.017) and RP (r = 0.543, p = 0.011), as well as emotions (RE) were associated with lower levels of albumin (r = 0.492, p = 0.024). In transplant recipients only, MCS (r = − 0.451, p = 0.040) was negatively associated with treatment duration, with the implication being that mental health deteriorated in accordance with a greater time lapse since transplantation. In transplant candidates, indicators of nutritional status such as pre-albumin and BMI, correlated with GH at baseline (pre-albumin: r = 0.401, p = 0.031 and BMI: r = 0.338, p = 0.025). However, among transplant recipients, indicators of nutritional status had significant associations with more HRQOL domains at 6 months, i.e. RP (r = 0.493, p = 0.038), RE (r = 0.493, p 0.038) and the MCS (r = 0.495, p = 0.037). The correlations of muscle (MAMC) with HRQOL scores were only evident among transplant recipients. There was a strong positive relationship between MAMC and the PCS (r = 0.821, p = 0.000) at baseline. MAMC also correlated with individual domains of physical, PF, RP, BP, and GH There was a weak negative association with MAMC and MCS (r = − 0.484, p = 0.042) (Table 5).

HRQOL—qualitative

Thirty-three males and 23 females (n = 56) provided narratives during the interviews. Of the total, 38 were on dialysis, while 18 were transplant recipients. The narratives were broadly aggregated into themes similar to those evaluated in the SF-36 (Table 6).

Discussion

This study reports the HRQOL in HIV-positive kidney transplant candidates and recipients from an HIV-positive donor. The SF-36 demonstrated reliability and validity, generating findings comparable to that of other studies but in a unique population [14, 31,32,33]. Given the complexity of HRQOL, no single method can fully evaluate this concept [34]. Hence the inclusion of interviews, for triangulation to corroborate either methods’ findings [35].

Transplant recipients

The present study’s recipients had high SF-36 scores indicating a good HRQOL. This concurs with previous study samples comparing candidates and recipients that were HIV-negative [36], as well as prospective studies of transplant recipients only, before and after their transplant [7].

Kovacs et al. also reported enhanced HRQOL in recipients, but added that this was not a finding consistent across all QOL domains [37], as unresolved issues potentially overshadow expected gains from the transplant [37]. These include treatment-related side effects and difficulties in resuming employment [37]. The present study saw high SF-36 scores across all domains, although worries about unemployment and financial constraints were mentioned in the interview, as were anxieties about graft rejection. These concerns, however, were outweighed by the positive changes following transplantation. Patients’ narratives, describing feelings of freedom, opportunities, and a second chance at a normal life, was in stark contrast to their recollections of life while on dialysis, and this was clearly evident in the high MH scores, which improved further after 6 months. Likewise, De Pascuale et al. observed that the mental freedom attained once dialysis ceased, resulted in feelings of psychological well-being which remained undiminished by other problems recipients may have experienced [38].

Still, mental health is an important area of investigation, as studies indicate that the prevalence of post-transplant depression ranges from 11.8 to 75% [39,40,41]. Depressive symptomatology were shown to be associated with negative outcomes such as sleep problems [42], poor adherence to treatment [43], and a 65% greater risk of mortality among transplant recipients [7].

Typical symptoms of depression [44], however, were not apparent among the present study’s recipients. Indeed, the MCS encompassing emotional (RE), mental (MH) and social (SF) well-being. (encompassing multiple aspects of psychological well-being), was higher than the average observed in the general population [45]. A possible contributor to their enhanced MH could be attributed to an adaptive response, given the presence of two chronic illnesses. Another could be recipients’ recollection of how terminally ill they were, as well as the impact that the diagnosis of ESRD had on their lives. Hence their current health status and related experiences were hardly comparable to their experience of dialysis. Another contributor to the MCS score were the high SF scores, and during the interviews, various social support networks at church, work or family and friends were mentioned. Indeed, research has shown that a lack of social support, apart from financial and employment stressors, was a key contributor to depressive symptoms in 59.2% of Chinese kidney transplant recipients [41]. The SF score improved further after 6 months, which Espisito and colleagues speculate is due to numerous hospital protocols in the immediate post-transplant period which limit social and emotional interactions [46]. Thereafter following the transition period, SF as well as other domains are likely to improve.

Transplant candidates

In the current study, no distinction was made between HD and PD candidates awaiting a transplant, as previous studies showed no significant differences in overall QOL between HD and PD patients [47,48,49]. All candidates predictably, had poorer HRQOL because ESRD and dialysis are known to adversely impact both physical and mental well-being [50].

PCS representing physical aspects of health, typically decreases relative to a deteriorating kidney function in CKD patients [51, 52]. Compromised physical health was apparent in the interviews, when candidates described considerable limitations in their activities of daily living due to feelings of fatigue, lack of energy and BP. Indeed, vitality (VT) scores, were the lowest of all domain scores and PCS was 47, falling at the lower end of the normal range of 47–53 [53].

Regarding psychological health, other researchers observed higher rates of depression among candidates versus recipients [54]. Although the MCS was lower among the current study’s candidates, it did not differ significantly from recipients. It is likely that they also benefitted from some ongoing social interactions. Frustration that dialysis and post-dialysis recovery restricts time available for engaging in social and leisure activities was expressed; however, without exception every candidate mentioned the presence of a support system such as a partner, family or church and work communities. Socialising offers known benefits such as mood enhancement, lowered depression and anxiety symptoms, and improved treatment compliance [55]. Furthermore, the support from the renal unit, (staff and patients on dialysis), appeared to be highly valued.

By the second assessment, MCS improved further, but candidates expressed certain anxieties and concerns underlying varying degrees of mental stress. Foremost among these, and similar to transplant recipients, were financial burdens related to a reduced income or unemployment.

Factors associated with HRQOL in both transplant candidates and recipients

Sociodemographic factors

Income appears to significantly impact QOL. In the general population, lower income corresponds to a lower QOL [56]. Among HIV-negative HD and PD patients, finances and unemployment are big concerns [47], while among transplant recipients, occupational status and financial burdens are associated with symptoms of depression [41].

In the present study, 20/47 (42.6%) of candidates were unemployed, higher than the 38.5% reported for Iranian HD and PD patients [57]. Although unemployment was higher among transplant recipients than candidates (52.4% versus 42.6%), candidates felt considerably greater stress, as travel expenses to the dialysis unit, incurred for HD, limited the availability of money that would normally be spent on food, education and leisure activities. The participants in this sample were either private patients with medical aid (insurance), or were public healthcare patients. Although most medical expenses, including medication were largely covered for both, private patients occasionally found that their benefits ‘ran out’ before year did, resulting in additional personal expenses. Doctors assisted by corresponding with employers, enabling some patients on dialysis to continue working, albeit part-time. However, they also expressed their frustration that the time required for dialysis and their lack of energy, made it challenging to retain employment. Although transplantation removed these limitations, seeking employment was then met with challenges facing the general population. In SA, unemployment has increased to 27.7% over the last decade [58], making it more difficult for South Africans in general to secure employment.

Employment is an important consideration in QOL, in view of its benefits. Being employed reduces stress through feelings of security, and enhances self-esteem, as one functions as a contributing member of society [59]. Furthermore it reduces feelings of guilt regarding family responsibility, especially where individuals were the main provider [41, 59]. Such feelings were indeed voiced by some candidates. Other studies concur. For example, in a Polish study of dialysed patients, QOL was most adversely affected by an inability to seek employment or study options [60]. In a Dutch sample of 34 transplant recipients, unemployed participants had significantly lower PF, RP, SF GH and poorer graft function than those who were employed [61]. Apart from employment, other notable sociodemographic factors in the present study were gender and age and level of education.

A reduction in physical function (PF) was observed with increasing participant age. A Malaysian study of transplant recipients also reported a negative correlation between age and the physical component score (PCS) [15]. However, the correlation in the present study was weak (r = 0.277, p = 0.022) probably because the study sample was still young (mean age 43.5 ± 8.1 years).

Male participants had significantly better HRQOL across all domains either at baseline, 6 months or both. These results are not unique to the transplant population, as similar results were documented among non-renal patients in South African and elsewhere [14, 36, 53, 62].

Level of education was positively correlated with the mental health component score (MCS) in Chinese HD and PD patients [63]. It is thought that more educated patients have a better QOL, as they possess a better understanding of their disease and management. This emphasises the importance of patient education on all aspects of their disease and management as an important tool to improve QOL. Indeed, participants in the current study consistently reported how their initial anxieties subsided after being educated by nursing staff about their treatment, especially dialysis.

Comorbidity

Transplant recipients with comorbidities have a lower HRQOL, evidenced in a study by Bohlke and colleagues, where participants with hypertension and diabetes demonstrated overall lower PCS scores [59]. Similar HRQOL effects would then be expected, in a recipient with comorbid HIV as HIV independently affects multiple dimensions of health and well-being [64]. Yet, this was not apparent in the present study.

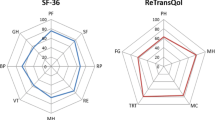

Despite a positive HIV status, the SF-36 scores and interviews of all participants in the current study, did not reflect the burden of two diseases. On the contrary, participants had better HRQOL when compared to patient groups elsewhere. Candidates on dialysis had higher HRQOL scores than HIV-negative dialysis patients in another South African study [47]. Secondly, this study’s transplant recipients also had higher HRQOL when compared to HIV-negative kidney transplant recipients elsewhere. Figure 4 compares, SF-36 domain scores with recipients from this study with recipients in Italy [46], Brazil [59], Norway [65] and Portugal [66]. Moreover, the PCS and MCS for this study’s recipients were above the average of the general population [16]. A possible explanation taken from Burholt et al. is that ratings may vary depending on how the questionnaire is administered. Interviewer administered questionnaires, as was the case in the current study, yield higher scores than self-administered ones [14]. However, based on the semi-structured interviews conducted in the current study, it would seem that the high scores documented, depicted the magnitude of change recipients perceived the transplant to have made to their lives. It could be assumed that recipients were most likely aware of the bleak outcome they would have faced without the option of a transplant.

Clinical and nutritional factors

In the current study, BMI, MAMC and pre-albumin were indicators of nutritional status. Albumin was considered an indicator of illness and inflammation [26], based on poor correlations with other nutritional markers in dialysed patients [67, 68]. Hypoalbuminemia was present in more candidates than recipients, and showed significant association with PCS and individual physical health domains. As an indicator of disease activity or illness, understandably, those with a higher level of illness would have a lower QOL.

As an indicator of protein stores and nutritional status, The National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) recommends the use of pre-albumin [26]. In the current study, the majority of candidates had pre-albumin levels that were within the normal range. GH, a subjective perception of one’s health status and a domain of physical health, was better at higher pre-albumin and BMI values. Other studies have also shown associations with several domains of physical aspects of health [69, 70]. However, in transplant recipients, pre-albumin correlated with more dimensions of health, i.e. not only with physical (RP), but also emotional (RE) and psychological (MCS) health.

In the present study, among recipients only, greater muscle mass (MAMC) was associated with better overall physical HRQOL (PCS) and its individual domains of PF, RP, BP and GH. Avoiding muscle attrition is therefore an important avenue for improving HRQOL, as evidence from studies of the elderly show that low muscle mass affects strength and impairs physical functional status and daily life [71]. In turn, physical functional ability is also related to psychological distress and well-being and has bearing on subjective views of health [72]. The finding that MAMC had a negative correlation with MCS in transplant recipients was unexpected. It is possible that MAMC increased over the 6-month follow-up period in relation to greater ambulation.

A strength of the current study is the use of a mixed methodology, with assessments done at two time points. The SF-36 had good psychometric properties and as the most widely used generic HRQOL tool, allowed comparisons with other populations. Furthermore, despite the small sample size, the findings were still generalizable as the majority of the patients on the transplant lists were included, thus being fairly representative of the group. Moreover, sample characteristics which are typically subject to regional variability [14], were offset by the fact that this was a multicentre study. Finally, participants varied in access to resources, educational attainment and occupational background, contributing to a heterogenous sample providing insight into the experiences of participants from varied backgrounds.

Conclusion

The current study findings concur with others, in that transplantation offers a superior HRQOL to dialysis. Furthermore, participants had better HRQOL scores compared to HIV-negative transplant recipients elsewhere. Going forward, interview narratives highlighted current positive healthcare practices and opportunities for optimising patient management. In particular, education from renal staff, which helped patients adjust to their disease and treatment protocol should be an ongoing HRQOL strategy for improving compliance and clinical health. Findings also suggest that clinicians should be aware of the significant impact of financial stress and unemployment on mental well-being. The provision of patient support to facilitate continued employment is of importance and should form part of routine enquiry when assessing patient mental health. Referral to a social worker or psychologist may also be beneficial. Finally, pre-albumin and MAMC were associated with SE, MCS and PCS, and as such, nutritional status impacts on physical, mental and emotional health. Therefore, regular assessment of these indicators and intervention through diet and physical activity may be effective behavioural approaches to improving HRQOL.

References

Frassetto, L. A., Tan-Tam, C., & Stock, P. G. (2009). Renal transpantation in patients with HIV. Nature Reviews. Nephrology, 5(10), 582–589.

Roland, M. E., Barin, B., Carlson, L., et al. (2008). HIV-Infected liver and kidney transplant recipients: 1- and 3- year outcomes. American Journal of Transplantation, 8(2), 355–365.

Trullas, J. C., Cofan, F., Tuset, M., et al. (2011). Renal transplantation in HIV-infected patients. Kidney International, 79(8), 825–842.

Muller, E., Kahn, D., & Mendelson, M. (2010). Renal transplantation between HIV-positive donors and recipients. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(24), 2336–2337.

Ortega, F., Valdés, C., & Ortega, T. (2007). Quality of life after solid organ transplanation. Transplantation Reviews, 21, 155–170.

Higginson, I. J., & Carr, A. J. (2001). Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ, 322(7297), 1297–1300.

Dew, M. A., Rosenberger, E. M., Myaskovsky, L., et al. (2015). Depression and anxiety as risk factors for morbidity and mortality after organ transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation, 100(5), 988–1003.

Griva, K., Davenport, A., & Newman, S. P. (2013). Health-related quality of life and long-term survival and graft failure in kidney transplantation: A 12-year follow-up study. Transplantation, 95(5), 740–749.

Laucis, N. C., Hays, R. D., & Bhattacharyya, T. (2015). Scoring the SF-36 in orthopaedics: A brief guide. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 97(19), 1628–1634.

Liem, Y. S., Bosch, J. L., Arends, L. R., Heijenbrok-Kal, M. H., & Hunink, M. G. (2007). Quality of life assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-Item health survey of patients on renal replacement therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health., 10(5), 390–397.

Ekberg, H., Kyllönen, L., Madsen, S., Grave, G., Solbu, D., & Holdaas, H. (2007). Increased prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with impaired quality of life in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation, 83(3), 282–289.

Posthouwer, D., Plug, I., van der Bom, J. G., Fischer, K., Rosendaal, F. R., & Mauser-Bunschoten, E. P. (2005). Hepatitis C and health-related quality of life among patients with hemophilia. Haematologica, 90(6), 846–850.

Home, P. D., Meneghini, L., Wendisch, U., et al. (2012). Improved health status with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 29(6), 716–720.

Burholt, V., & Nash, P. (2011). Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire: Normative data for Wales. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 33(4), 587–603.

Chiu, S. F., Wong, H. S., Morad, Z., & Loo, L. H. (2004). Quality of life in cadaver and living-related renal transplant recipients in Kuala Lumpur hospital. Transplantation Proceedings, 36(7), 2030–2031.

Stewart, M. (2007). The Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). The Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 53(3), 208.

Piotrowicz, K., Noyes, K., Lyness, J. M., et al. (2007). Physical functioning and mental well-being in association with health outcome in patients enrolled in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II. European Heart Journal, 28(5), 601–607.

Maglakelidze, N., Pantsulaia, T., Tchokhonelidze, I., Managadze, L., & Chkotua, A. (2011). Assessment of health-related quality of life in renal transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Transplantation Proceedings, 43(1), 376–379.

Cleemput, I., Kesteloot, K., Moons, P., et al. (2004). The construct and concurrent validity of the EQ-5D in a renal transplant population. Value Health., 7(4), 499–509.

Rodkjaer, L., Sodemann, M., Ostergaard, L., & Lomborg, K. (2011). Disclosure decisions: HIV-positive persons coping with disease-related stressors. Qualitative Health Research, 21(9), 1249–1259.

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Anthropometry Procedures Manual. [Online]; [cited 22/02/2014]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_an.pdf.

Afshar, M., Rebollo-Mesa, I., Murphy, E., Murtagh, F. E. M., & Mamode, N. (2012). Symptom burden and associated factors in renal transplant patients in the UK. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 44(2), 229–238.

Noori, N., Kopple, J. D., Kovesdy, C. P., et al. (2010). Mid-Arm muscle circumference and quality of life and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 5(12), 2258–2268.

World Health Organization. (2006). Global database on body mass index. [Online]; [cited 19/03/2019]. http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

Frisancho, A. R. (1974). Triceps skin fold and upper arm muscle size norms for assessment of nutritional status. The Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 27(10), 1052–1058.

Fouque, D., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kopple, J., et al. (2008). A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney. Kidney International, 73(4), 391–398.

Devoto, G., Gallo, F., Marchello, C., et al. (2006). Prealbumin serum concentrations as a useful tool in the assessment of malnutrition in hospitalized patients. Clinical Chemistry, 52(12), 2281–2285.

Venter, E., Gericke, G. J., & Bekker, P. J. (2009). Nutritional status, quality of life and CD4 cell count of adults living with HIV/AIDS in the Ga-Rankuwa re (South Africa). South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 22(3), 124–129.

Bertram, C., & Christiansen, I. (2014). Understanding research (p. 77). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

Turner, D. W., III. (2010). Qualitative interview design: A practical guide for novice investigators. TQR., 15(3), 754–760.

Brazier, J. E., Harper, R., Jones, N. M., et al. (1992). Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: New outcome measure for primary care. BMJ, 305(6846), 160–164.

Ruta, D. A., Abdalla, M. I., Garratt, A. M., Coutts, A., & Russell, I. T. (1994). SF 36 health survey questionnaire: I. Reliability in two patient based studies. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 3(4), 180–185.

Garratt, A. M., Ruta, D. A., Abdalla, M. I., & Russell, I. T. (1994). SF 36 health survey questionnaire: II.Responsiveness to changes in health status in four common clinical conditions. Qual Health Care., 3(4), 186–192.

Tariq, S., & Woodman, J. (2013). Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM Short Reports, 4(6), 2042533313479197. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042533313479197

Hussein, A. (2009). The use of Triangulation in Social Sciences Research: Can qualitative and quantitative methods be combined? JCSW. [Online]; [cited 19/03/2019]. http://www.bnemid.byethost14.com/NURSING%20RESEARCH%20METHODOLOGY%205.pdf?i=1

Rebollo, P., Ortega, F., Baltar, J. M., et al. (2000). Health related quality of life (HRQOL) of kidney transplanted patients: Variables that influence it. Clinical Transplantation, 14(3), 199–207.

Kovacs, A. Z., Molnar, M. Z., Szeifert, L., et al. (2011). Sleep disorders, depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional comparison between kidney transplant recipients and waitlisted patients on maintenance dialysis. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation, 26(3), 1058–1065.

De Pasquale, C., Veroux, M., Indelicato, L., et al. (2014). Psychopathological aspects of kidney transplantation: Efficacy of a multidisciplinary team. World Journal of Transplantation, 4(4), 267–275.

Anvar-Abnavi, M., & Bazargani, Z. (2010). Prevalence of anxiety and depression in Iranian kidney transplant recipients. Neurosciences (Riyadh), 15(4), 254–257.

Vásquez, V., Novarro, N., Valdés, R. A., & Britton, G. B. (2013). Factors associated to depression in renal transplant recipients in Panama. Indian J Psychiatry., 55(3), 273–278.

Lin, X., Lin, J., Liu, H., Teng, S., & Zhang, W. (2016). Depressive symptoms and associated factors among renal-transplant recipients in China. IJNSS., 3(4), 347–353.

Ronai, K. Z., Szentkiralyi, A., Lazar, A. S., et al. (2017). Depressive symptoms are associated with objectively measured sleep parameters in kidney transplant recipients. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(4), 557–564.

Jindal, R. M., Neff, R. T., Abbott, K. C., et al. (2009). Association between depression and nonadherence in recipients of kidney transplants: Analysis of the United States renal data system. Transplantation Proceedings, 41(9), 3662–3666.

World Health Organization. Depression. [Online]; 2018 [cited 07/03/2019]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

Ware, J. E., Jr., & Gandek, B. (1998). Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 903–912.

Esposito, P., Furini, F., Rampino, T., et al. (2017). Assessment of physical performance and quality of life in kidney-transplanted patients: A cross-sectional study. Clinical Kidney Journal, 10(1), 124–130.

Okpechi, I. G., Nthite, T., & Swanepoel, C. R. (2013). Health-related quality of life in patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation., 24(3), 519–526.

Tannor, E. K., Archer, E., Kapembwa, K., van Schalkwyk, S. C., & Davids, M. R. (2017). Quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis in South Africa: A comparative mixed methods study. BMC Nephrology, 18(4), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-016-0425-1

Homaie Rad, E., Mostafavi, H., Delavari, S., & Mostafavi, S. (2015). Health-related quality of life in patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: A meta-analysis of Iranian studies. Iranian Journal of Kidney Diseases, 9(5), 386–393.

Fukuhara, S., Lopes, A. A., Bragg-Gresham, J. L., et al. (2003). Worldwide Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Health-related quality of life among dialysis patients on three continents: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney International, 64(5), 1903–1910.

Gorodetskaya, I., Zenios, S., McCulloch, C. E., et al. (2005). Health-related quality of life and estimates of utility in chronic kidney disease. Kidney International, 68(6), 2801–2808.

McClellan, W. M., Abramson, J., Newsome, B., et al. (2010). Physical and psychological burden of chronic kidney disease among older adults. American Journal of Nephrology, 31(4), 309–317.

Kastien-Hilka, T., Rosenkranz, B., Sinanovic, E., Bennett, B., & Schwenkglenks, M. (2017). Health-related quality of life in South African patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174605

Szeifert, L., Molnar, M. Z., Ambrus, C., et al. (2010). Symptoms of depression in kidney transplant recipients: A cross-sectional study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 55(1), 132–140.

Gerogianni, S. K., & Babatsikou, F. P. (2014). Social aspects of chronic renal failure in patients undergoing haemodialysis. IJCS., 7(3), 740–745.

Lubetkin, E. I., Jia, H., Franks, P., & Gold, M. R. (2005). Relationship among sociodemographic factors, clinical conditions, and health-related quality of life: Examining the EQ-5D in the U.S. general population. Quality Life Research, 14(10), 2187–2196.

Parvan, K., Ahangar, R., Hosseini, F. A., Abdollahzadeh, F., Ghojazadeh, M., & Jasemi, M. (2015). Coping methods to stress among patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 26(2), 255–262.

Sulla, V., & Zikhali, P. (2018) Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa: an assessment of drivers, constraints and opportunities (English). Washington: World Bank Group. [Online]; [cited 24/01/2019]. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/Overcoming-Poverty-and-Inequality-in-South-Africa-An-Assessment-of-Drivers-Constraints-and-Opportunities

Bohlke, M., Marini, S. S., Rocha, M., et al. (2009). Factors associated with health-related quality of life after successful kidney transplantation: A population-based study. Quality of Life Research, 18(9), 1185–1193.

Dąbrowska-Bender, M., Dykowska, G., Żuk, W., Milewska, M., & Staniszewska, A. (2018). The impact on quality of life of dialysis patients with renal insufficiency. Patient Preference and Adherence, 12, 577–583.

van der Mei, S. F., Kuiper, D., Groothoff, J. W., van den Heuvel, W. J., van Son, W. J., & Brouwer, S. (2011). Long-term health and work outcomes of renal transplantation and patterns of work status during the end-stage renal disease trajectory. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 21(3), 325–334.

Uchmanowicz, B., Panaszek, B., Uchmanowicz, I., & Rosińczuk, J. (2016). Sociodemographic factors affecting the quality of life of patients with asthma. Patient Preference and Adherence, 10, 345–354.

Wu, F., Cui, L., Gao, X., et al. (2013). Quality of life in peritoneal and hemodialysis patients in China. Renal Failure, 35(4), 456–459.

Basavaraj, K. H., Navya, M. A., & Rashmi, R. (2010). Quality of life in HIV/AIDS. Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS, 31(2), 75–80.

Aasebø, W., Homb-Vesteraas, N. A., Hartmann, A., & Stavem, K. (2009). Life situation and quality of life in young adult kidney transplant recipients. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation, 24(1), 304–308.

Fructuoso, M., Castro, R., Oliveira, L., Prata, C., & Morgado, T. (2011). Quality of life in chronic kidney disease. Nefrología, 31(1), 91–96.

Friedman, A. N., & Fadem, S. Z. (2010). Reassessment of albumin as a nutritional marker in kidney disease. JASN., 21(2), 223–230.

Gama-Axelsson, T., Heimbürger, O., Stenvinkel, P., Bárány, P., Lindholm, B., & Qureshi, A. R. (2012). Serum albumin as predictor of nutritional status in patients with ESRD. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 7(9), 1446–1453.

Wu, L. W., Lin, Y. Y., Kao, T. W., et al. (2017). Mid-arm muscle circumference as a significant predictor of all-cause mortality in male individuals. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171707

Rambod, M., Kovesdy, C. P., Bross, R., Kopple, J. D., & Kalantar-Zadeh, K. (2008). Association of serum prealbumin and its changes over time with clinical outcomes and survival in patients receiving hemodialysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 88(6), 1485–1494.

Amarantos, E., Martinez, A., & Dwyer, J. (2001). Nutrition and quality of life in older adults. Journal of Gerontology, 56A, 54–64.

Schulz, T., Niesing, J., Stewart, R. E., et al. (2012). The role of personal characteristics in the relationship between health and psychological distress among kidney transplant recipients. Social Science and Medicine, 75(8), 1547–1554.

Funding

This study was made possible through financial support from the 1. National Research Foundation (NRF) Grant ID: 94193, 104599. 2. The South African Sugar Association (SASA): Project 246. 3. Haley Stott Grant. The funders did not contribute to the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data and writing of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, C.J., Muller, E., Labadarios, D. et al. Health-related quality of life and associated factors in HIV-positive transplant candidates and recipients from a HIV-positive donor. Qual Life Res 31, 171–184 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02898-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02898-y