Abstract

Purpose

Epilepsy is a global public health problem that causes a profound physical, psychological and social consequences. However, as such evidence in our country is limited, this study aimed to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and associated factors among patients with epilepsy.

Methods

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted on 370 patients with epilepsy. The Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-31 (QOLIE-31) was used to measure HRQOL. Multiple linear regression was fitted to assess the association between HRQOL and the independent variables, and a P-value < 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval were used to declare statistical significance.

Results

More than 55% of the participants were male, and the mean age of the participants was 29.64 (11.09) years. The overall HRQOL score was 55.81 (14.00). The scale scores ranged from 46.50 (15.55) to 64.98 (19.43). Out of the seven scales, the energy scale score was the lowest. Frequency of seizure, anxiety, depression, perceived stigma and adverse drug event were negatively associated with HRQOL, whereas social support had a significant positive association.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the HRQOL of patients was low and that its energy and emotional scales were the most affected. The presence of depression, anxiety and stigma adversely affected patient HRQOL. Therefore, healthcare professionals should be aware of the emotional state of the role it plays for HRQOL. Interventions aimed at reducing psychosocial problems and stigmatization are also needed to improve the patient HRQOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Epilepsy is a non-communicable neurological condition characterized by recurrent unpredictable seizures. A seizure happens when abnormal electrical activities occur in the brain and cause involuntary changes in body movement, sensation, awareness or other cognitive functions. More than 50 million people, 80% of whom were from developing countries, were affected globally with an incidence rate of 4 to 10 per 1000 people [1]. Approximately, an estimated 4.4 million people had active epilepsy in Sub-Sharan Africa, and the greatest number of cases was among those aged 20–29 years [2]. In Ethiopia, the prevalence was approximately 5.2 per 1000 people [3].

Epilepsy is a global public health problem that causes major disruptions associated with profound physical, psychological and social consequences. A patient with epilepsy faces many challenges, including emotional changes (depression and anxiety), stigma, low social support, and economic problems which have impacts on patient health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [4]. Previous studies showed the HRQOL of patients with epilepsy was poorer compared to that of healthy individuals [5, 6]. Even though the primary goal of treating patients with anti-epileptic drugs (AED) is to control seizure and further complications, the side effects of the drugs can be significant and may interfere with the patients’ HRQOL [7]. The most frequently used drugs, in Ethiopia, are Phenobarbital, Carbamazepine, Valproic acid and Phenytoin [8, 9].

Quality of life (QOL) is broader than HRQOL because it includes the evaluation of non-health-related features. HRQOL is, however, connected to an individual’s health or disease status and helps us understand the distinction between aspects of life related to health. It is a broad-ranging concept incorporating the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs in a complex way and focuses on the impact health status has on QOL [10, 11].

The burden of epilepsy can overwhelmingly affect patients, their families and the society in general. Many people in Africa including Ethiopia believe that epilepsy is contagious, and patients may need to isolate themselves because people most often stigmatize them. This may lead to loss of their self-confidence and embarrassment and depression [12]. Moreover, physical injuries such as falls, burns, drowning and car accidents can threaten their lives [4].

Predictors of HRQOL of patients with epilepsy can be grouped as psychosocial, neuro-epilepsy and medication related [13]. Literature indicates that depression [14,15,16], anxiety [16,17,18,19], social support [20], stigma [21], number and frequency of medication used [15, 22], adverse drug events (ADE) [16, 23, 24], frequency of seizure [16, 19, 25], education [24, 26], gender [20, 27], age [26] and duration of illness [28] are variables associated with HRQOL.

Although a few studies have been done in Ethiopia, evidence remains limited, suggesting the need for further research. Studies at Amanuel mental specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, and Ambo general hospital used the WHOQOL-Bref questionnaire [16], which is a generic tool. Two other studies used Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-31 (QOLIE-31), a specific tool [29, 30]. However, the association between predictors and HRQOL was investigated only with correlation. In addition, psychosocial variables like, social support and perceived stigma were missing in their studies. There is a socio-cultural difference and no study has been conducted in the current study area.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the HRQOL among patients with epilepsy and associated factors by considering socio-demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables at the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital.

Methods

Study design and setting

This facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted at the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital (UoGCSH) Chronic Illness Follow-up Outpatient department (OPD) from March to April 2019, to assess HRQOL and associated factors among patients with epilepsy. The hospital is one of the tertiary-level facilities in the Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. It serves about seven million people in and around the North Gondar zone as a referral center for lower-level health facilities in the area. It provides inpatient and outpatient as well as chronic illness follow-up services. At the moment, it was treating patients with epilepsy who visited it for the first time and referred patients. The chronic illness follow-up OPD works five days a week and serves patients with neurologic disorders, including epilepsy, two days per week.

Sample size and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated using the single mean estimation formula from a previous study in Mekele city [29] by considering 26.43 standard deviation, a 95% confidence level, 4% margin of error and 10% non-response rate. This yielded 376 as a sample size.

The population was all adult patients with epilepsy at the chronic illness follow-up OPD during the study. When patients came to the OPD, they were screened for inclusion criteria. Those who fulfilled the criteria and volunteered to participate were included. All patients aged at least 18 years, diagnosed with epilepsy for at least one year and were taking AED at the time qualified for the study. Patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, stroke, head injury, brain tumors and unable to communicate were excluded. Consecutive sampling was used to recruit study participants until the required sample size was reached.

Data collection tools and procedure

Data were collected on socio-demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables and HRQOL. The questionnaire was first prepared in English and translated to the local language, Amharic, and retranslated to the English language for matters of consistency.

Health-related quality of life

The QOLIE-31 questionnaire, a specific tool used in similar studies in Ethiopia [29, 30], was employed to assess HRQOL. It contains 31 items computed into seven scales that assess seizure worry, overall QoL, emotional well-being, energy/fatigue, cognitive functioning, anti-epileptic medication effects and social functioning [31]. The raw precoded numeric values of items were recoded to 0–100 score; then, the subtotal score was calculated for each scale. The overall score was calculated by weighing and summing scale scores. The scores on each scale ranged from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better HRQOL [32].

Social support

Social support was measured by the Oslo-3 items social support scale (Oslo SSS), which has three items with a Likert scale. The questions were “How easily can you get help from neighbors if you should need it?” “How many people are so close to you that you can count on them if you have serious problems?” and “How much concern do people show in what you are doing?” The Likert scales of the first and third items were coded to 1–5 score and the second item was coded to 1–4 score. A sum index was made by summarizing the raw scores; it ranged from 3 to 14. A score of 3–8 was “poor social support”, 9–11 was “moderate social support” and 12–14 was “strong social support” [33].

Perceived stigma

Perceived stigma was measured by the Kilifi Stigma Scale of Epilepsy, developed and validated in Kilifi, Kenya. It is a simple three-point Likert scoring system scored as “not at all” (score of 0), “sometimes” (score of 1) and “always” (score of 2). It has fifteen items and the total score was calculated by the addition of all item scores. The higher the score, the greater the sense of stigma perceived [34, 35].

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression variables were measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [36]. It is a brief and internationally used self-rating scale with 14 items, which seeks to identify anxiety and depression. All items are to be answered on four-point scales between 0 and 3. Two subscale scores were computed by simply adding the raw scores of each scale (range = 0–21). Anxiety and depression were classified as not depressed/ anxious (0–7), borderline (8–10) and depressed/ anxious (11–21).

Adverse drug event

Patients were asked to disclose any suspected adverse drug events, such as sedation, gastrointestinal disturbance, fatigue, dizziness, headache, tiredness, loss of appetite, over the last three months due to their AED.

Wealth index

Wealth index we used an asset-based approach. The collected information was on ownership of a range of durable assets (e.g. car, refrigerator and television) and housing characteristics (e.g. material of dwelling floor and roof and toilet facilities). We asked the patients whether they had the above assets. This approach has been used in the Demographic and Health Survey, and we adapt questions from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey [37]. For the computation of the index, a principal component analysis was used, and patients were divided into three groups according to their level of wealth.

Some clinical characteristics (duration of illness and number of drugs) were collected from the patient’s medical record. A pretest was done on 5% of the total sample size out of the study area. Two days of intensive training was given to the data collectors on the questionnaire and how to collect the data.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, means (SD) and frequencies (percentages) were calculated for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The computation of HRQOL scale scores and other independent variables (anxiety, depression, stigma and social support) were done based on their manuals. A simple linear regression was done to select variables for the final model, and variables with < 0.2 P-value were selected. A multiple linear regression was fitted to assess the associations between HRQOL and the independent variables. The model assumptions for linear regression such as normality, linearity, equality of variance, and multicollinearity were checked. A P-value < 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval were used to declare statistical significance. The internal reliability of the Amharic version of the QOLIE-31 was checked by calculating Cronbach alpha, and all analyses were done by STATA Version 14.

Results

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

A total of 376 participants were interviewed with a 98.40% response rate. Of the respondents, 55.41% were male, and the mean (SD) age of the participants was 29.64 (11.09) years. Approximately 28% of the participants had seizures more than three times a year; 35.13% and 53.24% had anxiety and depression, respectively (Table 1).

Overall HRQOL and scale scores of participants

This study showed that the overall mean score for HRQOL was 55.81 (14.00). Out of the seven scales, the social function scale score was the highest (64.98), whereas the energy/fatigue scale score was the lowest (46.50) (Table 2). The internal reliability coefficient (Cronbach alpha) of the QOLIE-31 was 0.70.

Factors associated with the HRQOL

The model assumptions of the multiple linear regression, such as normality, linearity, equality of variance and multicollinearity were fulfilled. Socio-demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables were independently associated with HRQOL at P-value < 0.05 after adjusting for covariates. The multiple linear regression analysis revealed that the psychosocial variables, like anxiety, depression and stigma were negatively associated with HRQOL. As their score increased by one, the HRQOL score decreased by 0.70 (P < 0.001), 0.94 (P < 0.001) and 0.47 (P < 0.001) points, respectively, while controlling for other variables in the model. As the social support score increased by one, the HRQOL score also increased by 0.59 (P = 0.003) other variables being fixed. Depression and stigma had the greatest impact on HRQOL (as indicated by the standardized regression coefficient). Patients with ADE scored an average of 4.13 (P = 0.002) points lower relative to patients without ADE. Finally, patients who had seizures more than three times a year scored an average of 3.94 (P = 0.004) points lower compared to patients who were seizure-free in a year. However, age, duration of illness, frequency of drug, number of drugs, wealth index, occupation, marital status and education did not have a significant association with HRQOL in the multiple linear regression analysis (Table 3).

Discussion

The current study aimed to assess HRQOL and associated factors among patients with epilepsy at the UoGCSH. In this study, the overall score of HRQOL was 55.81 (14.01) and the scale scores ranged from 64.98 (19.43) to 46.50 (15.55). Frequency of seizure, anxiety, depression, perceived stigma, ADE and social support had a significant association with the overall HRQOL.

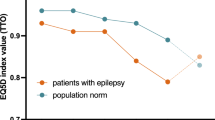

Epilepsy disrupts an individual’s physical, psychological and social dimensions of health. This finding also revealed that epilepsy compromised patient HRQOL. The energy and emotional scale scores were severely affected, and patients often experienced emotional problems. This was supported in that in the current study 83% and 63% of patients had different degrees of depression and anxiety, respectively. A study in Turkey also revealed that the mental component of the HRQOL of patients was lower than that of the normal population [38]. Moreover, epilepsy hinders the process of social information and social interaction due to cognitive and affective problems [39]. According to literature, one of the major consequences of epilepsy is stigma [40, 41]. One study also revealed that among different chronic illnesses, epilepsy was second only to HIV as the cause of stigma [42]. Generally, epilepsy has multi-dimensional impacts of reducing patient HRQOL.

The overall HRQOL score of this study is lower than those of studies in Jimma (58.8 ± 10.6) and Mekele city (77.9 ± 20.7), Ethiopia [29, 30]. A possible explanation might be that percentage of patients with depression, in Jimma’s study, is lower than this study, and a higher number of patients, in Mekele’s study, were taking only one drug a day. In our study, 29.46% of patients were seizure-free for a year, which seems they had controlled epilepsy status. However, even if seizure status is one important clinical parameter for the severity of the disease, patient’s perception and well-being might not be directly proportional to physiological and clinical abnormalities, and the effects flowing from clinical abnormalities to HRQOL are mediated and modified by psychological, social and cultural factors [43]. Therefore, the socio-cultural difference might explain the variance. Moreover, the time frame for the inclusion of study population, duration of patients on anti-epileptic drugs, was different: at least three months for Jimma; six months for Mekele; one year for ours. Other studies from Amanuel Mental specialized hospital (Addis Abeba), Ambo, Ethiopia, [16], Tunisia [6] and Kenya [5] showed the domains’ scores were above the average, signifying higher HRQOL. The studies seem comparable to the current one although a direct comparison might be difficult because the other studies used a different tool (WHOQOL-BREF and SF-36).

The findings in Uganda (58.1), India (64.61), Taiwan (63.96), Japan (62.7) Germany (69.32) and Greece (68.5) [15, 20, 24, 25, 44,45,46] are higher than ours. Perhaps because the emotional well-being scale of this study is lower than those of studies. The emotional change may lead to anxiety and depression, which affects the psychological aspect of life as well as physical and social functioning. Furthermore, there might be a difference in socio-cultural and healthcare delivery.

The second objective of the study was to identify factors associated with HRQOL. In this study, psychosocial variables (depression, anxiety, poor social support and stigma) and medication-related factors, such as ADE were the most important because they had associations with lower HRQOL. In addition, the frequency of seizure had an association with HRQOL. All of the psychosocial variables had a significant association with the overall score of HRQOL. For example, depression and stigma showed the strongest impact on HRQOL, even more so than anxiety, social support, ADE and seizures. The strength of association of anxiety, ADE and frequency of seizure were comparable. This signifies apart from socio-demographic and clinical variables, psychosocial and medication-related variables were vital in determining patient HRQOL.

Depression, anxiety and stigma had an association with lower HRQOL. That is, patients with one or more of the above conditions had a lower HRQOL. Although all of the psychosocial variables were statistically significant, depression and stigma had the greatest impact on HRQOL. Different studies are also in line with the current finding [14,15,16,17,18,19]. For example, stigma is common among patients with epilepsy in both developed and developing countries [13]. It hinders an active seeking of treatment or reduces adherence and the day to day activities of patients. Furthermore, it causes depression, social withdrawal and poor social interaction [47]. The other common psychosocial factors are depression and anxiety; research has documented that people with epilepsy are more likely to experience anxiety and depression, which have an impact on the patient's life [4]. Finally, as patients get more social support, their HRQOL becomes good. Social capital, such as social networks, has an impact on the production of health and well-being. People who have good social support are less likely to experience negative feelings, like sadness, loneliness and low self-esteem (28). Accordingly, social support is a means, especially of patients with chronic diseases, like epilepsy, of getting support relating to medication, eating and self-confidence that can improve well-being.

Among the second group of variables, ADE had association with HRQOL. Patients with ADE had a lower HRQOL than their counterparts. Evidence indicated that ADE (side effect) had the potential to negatively affect the lives of individuals with epilepsy and impact their HRQOL [7, 46, 48].

Patients who experienced seizures more than three times a year had a lower HRQOL than those with seizure-free years. The finding is comparable to those of other studies [19, 25]. As it results in injuries, hospitalization, depression and anxiety, epilepsy has physical and psychological impacts on patients and limits their day to day activities [4]. It limits the day to day activities of the patients. Moreover, worries patients have about the seizure and what may happen to them in the future also affect patient wellbeing [49].

Limitation of the study

As a cross-sectional attempt, this work detected only associations, not causalities. The findings might not be representative of patients in other settings: the study was conducted at a single institution and a significant number of patients seemed to have well-controlled epilepsy, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the HRQOL of patients was relatively low in all scales and the overall HRQOL scores compared to those of other studies. It also showed that the energy and emotional well-being scale scores were the most affected. Therefore, healthcare professionals should be aware of the significance of patients’ emotional states and the role it plays in their HRQOL. Moreover, our findings suggested that HRQOL in patients with epilepsy might be adversely affected to a substantial degree by the presence of depression, anxiety and stigma. Interventions aimed at reducing psychosocial problems, changing community attitudes and behaviors and decreasing stigmatization are also needed to improve patient HRQOL. Finally, follow-up studies at more health facilities are suggested to examine the impact of epilepsy and contributing factors.

Data Availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available upon request to the corresponding author. Due to data protection restrictions and participant confidentiality, we do not make participants' data publicly available.

References

World Health Organization (2018). Epilepsy. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy.

Paul, A., Adeloye, D., George-Carey, R., Kolčić, I., Grant, L., & Chan, K. Y. (2012). An estimate of the prevalence of epilepsy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic analysis. Journal of Global Health, 2(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.02.020405.

Worku, D. (2013). Review article: Epilepsy in Ethiopia (Vol. 333).

Kerr, M. P. (2012). The impact of epilepsy on patients' lives. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 126(S194), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12014.

Kinyanjui, D. W. C., Kathuku, D. M., & Mburu, J. M. (2013). Quality of life among patients living with epilepsy attending the neurology clinic at kenyatta national hospital, Nairobi, Kenya: a comparative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 11(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-98.

Mrabet, H., Mrabet, A., Zouari, B., & Ghachem, R. (2004). Health-related quality of life of people with epilepsy compared with a general reference population: a Tunisian study. Epilepsia, 45(7), 838–843.

Perucca, P., Gilliam, F. G., & Schmitz, B. (2009). Epilepsy treatment as a predeterminant of psychosocial ill health. Epilepsy & Behavior, 15(2), S46–S50.

Gurshaw, M., Agalu, A., & Chanie, T. (2014). Anti-epileptic drug utilization and treatment outcome among epileptic patients on follow-up in a resource poor setting. Journal of Young Pharmacists, 6(3), 47.

Ayalew, M. B., & Muche, E. A. (2018). Patient reported adverse events among epileptic patients taking antiepileptic drugs. SAGE Open Med, 6, 2050312118772471.

Calman Kc, E. (2019). Quality of life and health related quality of life – is there a difference?. Evidence Based Nursing 2014–2014.

Karimi, M., & Brazier, J. (2016). Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics, 34(7), 645–649.

Baskind, R., & Birbeck, G. L. (2005). Epilepsy-associated stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: the social landscape of a disease. Epilepsy & Behavior, 7(1), 68–73.

Baker, G. A. (2002). The psychosocial burden of epilepsy. Epilepsia, 43(6), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.6.12.x.

Choi-Kwon, S., Chung, C., Kim, H., Lee, S., Yoon, S., Kho, H., et al. (2003). Factors affecting the quality of life in patients with epilepsy in Seoul South Korea. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 108(6), 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00151.x.

Endermann, M., & Zimmermann, F. (2009). Factors associated with health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among young adults with epilepsy and mild cognitive impairments in short-term residential care. Seizure, 18(3), 167–175.

Tegegne, M. T., et al. (2014). Assessment of quality of life and associated factors among people with epilepsy attending at Amanuel Mental. Science Journal of Public Health, 2(5), 378–383.

Lee, S. J., Kim, J. E., Seo, J. G., Won, Y., Lee, J. J., Moon, H. J., et al. (2014). Predictors of quality of life and their interrelations in Korean people with epilepsy A MEPSY study. Seizure European Journal of Epilepsy, 23(9), 762–768.

Meldolesi, G. N., Picardi, A., Quarato, P. P., Grammaldo, L. G., Esposito, V., Mascia, A., et al. (2006). Factors associated with generic and disease-specific quality of life in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy research, 69(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.01.010.

Melikyan, E., & Guekht, A. (2012). Health-related quality of life in Russian adults with epilepsy: The effect of socio-demographic and clinical factors. Epilepsy and Behavior, 25(4), 670–625.

Chen, H.-F., Tsai, Y.-F., Hsi, M.-S., & Chen, J.-C. (2016). Factors affecting quality of life in adults with epilepsy in Taiwan: a cross-sectional, correlational study. Epilepsy & Behavior, 58, 26–32.

Ayenalem, A. E., Tiruye, T. Y., & Muhammed, M. S. (2017). Impact of Self Stigma on Quality of Life of People with Mental Illness at Dilla University Referral Hospital, South Ethiopia. American Journal of Health Research, 5(5), 125–130.

Yue, L., Yu, P., et al. (2011). Determinants of quality of life in people with epilepsy and their gender differences. Epilepsy and Behavior, 22(4), 692–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.08.022.

George, J., Kulkarni, C., Epilepsy, C. C., & Sarma, G. R. K. (2015). Antiepileptic drugs and quality of life in patients with epilepsy : a tertiary care hospital-based study. Value in Health Regional Issues, 6, 1–6.

Nabukenya, A. M., Matovu, J. K. B., Wabwire-Mangen, F., Wanyenze, R. K., & Makumbi, F. (2014). Health-related quality of life in epilepsy patients receiving anti-epileptic drugs at National Referral Hospitals in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-49.

Canuet, L., Ishii, R., Iwase, M., Ikezawa, K., Kurimoto, R., Azechi, M., et al. (2009). Factors associated with impaired quality of life in younger and older adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy research, 83(1), 58–65.

Djibuti, M., & Shakarishvili, R. (2003). Influence of clinical, demographic, and socioeconomic variables on quality of life in patients with epilepsy: findings from Georgian study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 74(5), 570–573.

Alanis-Guevara, I., Peña, E., Corona, T., López-Ayala, T., López-Meza, E., & López-Gómez, M. (2005). Sleep disturbances, socioeconomic status, and seizure control as main predictors of quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsy and Behavior, 7(3), 481–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.06.010.

Shetty, P. H., Naik, R. K., Saroja, A., & Punith, K. (2011). Quality of life in patients with epilepsy in India. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 2(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-3147.80092.

Gebre, A. K. (2018). Sociodemographic, clinical variables, and quality of life in patients with epilepsy in Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia. Behavioral Neurology, 2018, 1–6.

Shiferaw, D., & Hailu, E. (2015). Quality of Life Assessment among Adult Epileptic Patients Taking Follow Up Care at Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma, South West Ethiopia: Using Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-31instrument. Global Jourenal of Medical Research, 18(3).

RAND HEALTH CARE Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-31 (QOLIE-31) https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/health/surveys_tools/qolie/qolie31_survey.pdf

RAND HEALTH CARE Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-31 (QOLIE-31) Scoring Instructions. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/health/surveys_tools/qolie/qolie31_scoring.pdf

Dalgard, O. S., Dowrick, C., Lehtinen, V., Vazquez-Barquero, J. L., Casey, P., Wilkinson, G., et al. (2006). Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(6), 444–451.

Mbuba, C. K., Abubakar, A., Odermatt, P., Newton, C. R., & Carter, J. A. (2012). Development and validation of the Kilifi Stigma Scale for Epilepsy in Kenya. Epilepsy and Behavior : E&B, 24(1), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.02.019.

Fanta, T., Azale, T., Assefa, D., & Getachew, M. (2015). Prevalence and factors associated with perceived stigma among patients with epilepsy in Ethiopia. Psychiatry Journal, 2015, 1–7.

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3.

Agency, C. S. (2016). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville (p. 2016). Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF.

Mutluay, F. K., Gunduz, A., Tekeoglu, A., Oguz, S., & Yeni, S. N. (2016). Health related quality of life in patients with epilepsy in Turkey. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 28(1), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.28.240.

Steiger, B. K., & Jokeit, H. (2017). Why epilepsy challenges social life. Seizure, 44, 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2016.09.008.

Bifftu, B. B., Dachew, B. A., & Tiruneh, B. T. (2015). Perceived stigma and associated factors among people with epilepsy at Gondar University Hospital , Northwest Ethiopia : a cross-sectional institution based study. African health science, 15(4).

Shibre Teshome, A. A., Redda, T.-H., Girmay, M., & Lars, J. (2006). Perception of stigma among family members of patients epilepsy and their relatives in Butajira. Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev., 20(3), 170–176.

Fernandes, P. T., Salgado, P. C. B., Noronha, A. L. A., Barbosa, F. D., Souza, E. A. P., Sander, J. W., et al. (2007). Prejudice towards chronic diseases: Comparison among epilepsy AIDS and diabetes. Seizure, 16(4), 320–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2007.01.008.

Ormel, J., Lindenberg, S., Steverink, N., & Vonkorff, M. (1997). Quality of life and social production functions: A framework for understanding health effects. Social Science and Medicine, 45(7), 1051–1063.

Haritomeni, P., Aikaterini, T., Theofanis, V., Elizabeth, D., Ioannis, H., Konstantinos, V., et al. (2006). The Greek version of the quality of life in epilepsy inventory (QOLIE-31). Quality of life research, 15(5), 833–839.

Kubota, H., & Awaya, Y. (2010). Assessment of health-related quality of life and influencing factors using QOLIE-31 in Japanese patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy and Behavior, 18(4), 381–387.

Pimpalkhute, S. A., Bajait, C. S., Dakhale, G. N., Sontakke, S. D., Jaiswal, K. M., & Kinge, P. (2015). Assessment of quality of life in epilepsy patients receiving anti-epileptic drugs in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Indian Journal of Pharmacology, 47(5), 551–554. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7613.165198.

Salih, M. H., & Landers, T. (2019). The concept analysis of stigma towards chronic illness patient. Hospice and Palliative Medicine International Journal, 3(4), 132–136. https://doi.org/10.15406/hpmij.2019.03.00166.

Baker, G. A., Jacoby, A., Buck, D., Stalgis, C., & Monnet, D. (1997). Quality of life of people with epilepsy: A European study. Epilepsia, 38(3), 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01128.x.

Loring, D. W., Meador, K. J., & Lee, G. P. (2004). Determinants of quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsy and Behavior, 5(6), 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.08.019.

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to the University of Gondar for the approval of the ethical issue and its technical and financial support. We forward our appreciation to the hospital managers for allowing us to conduct this research and their cooperation. Finally, we would like to thank study participants for their volunteer participation and also data collectors and supervisors for their genuineness and quality of work during data collection.

Funding

This is part of a master thesis funded by the University of Gondar. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Science, University of Gondar (Ref. No.: IPH/180/2019). Permission letters were obtained from the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital. All study participants were oriented on the objectives and purpose of the study before study participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were explained. Patients at health facilities and sick individuals were informed that participation had no impact on the provision of their health care. Written informed consent was obtained, and study team members safeguarded the confidentiality and anonymity of study participants throughout the entire study. Interviews were conducted in quiet areas, enclosed whenever possible, to ensure participant privacy. In order to protect the identities of the study participants, each participant was given a unique identification number (ID). Participation in the study was voluntary and individuals were free to withdraw or stop the interview at any time.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Addis, B., Minyihun, A. & Aschalew, A.Y. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among patients with epilepsy at the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital, northwest Ethiopia. Qual Life Res 30, 729–736 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02666-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02666-4