Abstract

Purpose

Connections between private religion/spirituality and health have not been assessed among US South Asians. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between private religion/spirituality and self-rated and mental health in a community-based sample of US South Asians.

Methods

Data from the Mediators of atherosclerosis in South Asians living in America (MASALA) study (collected 2010–2013 and 2015–2018) and the attendant study on stress, spirituality, and health (n = 881) were analyzed using OLS regression. Self-rated health measured overall self-assessed health. Emotional functioning was measured using the mental health inventory-3 index (MHI-3) and Spielberger scales assessed trait anxiety and trait anger. Private religion/spirituality variables included prayer, yoga, belief in God, gratitude, theistic and non-theistic spiritual experiences, closeness to God, positive and negative religious coping, divine hope, and religious/spiritual struggles.

Results

Yoga, gratitude, non-theistic spiritual experiences, closeness to God, and positive coping were positively associated with self-rated health. Gratitude, non-theistic and theistic spiritual experiences, closeness to God, and positive coping were associated with better emotional functioning; negative coping was associated with poor emotional functioning. Gratitude and non-theistic spiritual experiences were associated with less anxiety; negative coping and religious/spiritual struggles were associated with greater anxiety. Non-theistic spiritual experiences and gratitude were associated with less anger; negative coping and religious/spiritual struggles were associated with greater anger.

Conclusion

Private religion/spirituality is associated with self-rated and mental health. Opportunities may exist for public health and religious care professionals to leverage existing religion/spirituality for well-being among US South Asians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Religious and spiritual (R/S) beliefs and practices play an important role in the lives of many Americans, with 91% of adults in the United States (US) reporting belief in God or a higher power. While some R/S indicators such as confident belief in God and religious attendance have seen modest declines in recent decades, others, such as belief in an afterlife, have seen modest increases [1].

R/S and health research has frequently focused on communal dimensions of individuals’ spirituality, such as religious service attendance, and to a lesser extent on private dimensions (e.g., individual prayer, meditation, beliefs) [2, 3]. R/S health research in the US has also focused largely on the majority white Christian population. These two limitations—focus on communal practice and lack of religious, racial, and ethnic diversity—comprise an important gap in this area of knowledge. The current study seeks to fill this gap by examining relationships between health and a range of private R/S beliefs and practices in a community-based sample of US South Asians.

In addition to addressing an important gap in extant research, this study is important for three reasons. First, South Asians (those of Asian Indian, Nepali, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or Sri Lankan heritage) have received almost no attention in the religion and health literature [4,5,6], yet South Asians are one of the fastest growing US minority groups [7]. Second, previous non-South Asian research has not only found meaningful associations between private R/S and physical and mental health [2, 3, 8,9,10], but also that race and ethnicity are important contingencies [11, 12]. Third, many faiths in South Asia (e.g., Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism) do not have consistent expectations regarding regular public religious participation [13]; therefore, studying private religion among South Asians is especially salient.

In the US, R/S beliefs and practices are often, though not always, positively associated with health outcomes. The positive health effects of R/S are thought to arise from the provision of a range of resources including sense of meaning, enhanced self-concept, intervals of respite, social support, and perceived divine relations and support [14]. However, the health effects of some aspects of R/S are deleterious and thought to arise due to cognitive dissonance, feelings of shame and guilt, negative interactions with co-religionists, and other spiritual struggles [9]. Some of these positive and negative findings have been observed among majority Christian whites, African Americans, and Latinos in the US [15, 16], but almost nothing is known about Hindus, Muslims, and members of other religious groups in the US South Asian community [17]. The authors are only aware of one community-based study examining private religion and health among US Asian Indians, indicating that religiosity is inversely associated with negative affect, but not related to positive affect [18].

The vast majority of South Asians adhere to Dharmic (e.g., Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, Buddhism) faiths, which engender distinct approaches to R/S, often espousing beliefs regarding inner peace, harmony, connection to nature, and emptying of self. Yoga (meaning “union”) has Dharmic roots and is practiced in various expressions of South Asian R/S. Further, Dharmic R/S frequently centers on individual and family practices performed in the home (e.g., pujah), which differs from more congregation-based religions [19].

Islam is also practiced by South Asians. While Muslim R/S occurs in public settings such as mosques and Islamic centers, about one quarter of US Muslims seldom or never attend a mosque [20], and private R/S is an important component of Muslim spirituality [21]. Prayer punctuates the day for many Muslims, often in private spaces. Other spiritual practices occur in homes and are embedded in the complex beliefs of individuals who interpret Islam in diverse ways [22]. These myriad practices reflect the multidimensional nature of R/S [23, 24].

The current study investigated private R/S and health using the Mediators of Atherosclerosis among South Asians living in America (MASALA) study with ancillary measures from the Study on Stress, Spirituality, and Health (SSSH). An array of private R/S measures was examined in relation to four health outcomes: self-rated health, emotional functioning, anxiety, and anger. The R/S measures available in the SSSH enabled the evaluation of eleven theistic and non-theistic variables, capturing a range of private beliefs, practices, and experiences. The investigators expected beneficial associations between health outcomes and individual prayer, yoga practice, gratitude, daily spiritual experiences, belief in God, closeness to God, positive religious coping, and divine hope. Deleterious associations were expected for negative religious coping and R/S struggles.

Methods

Participants

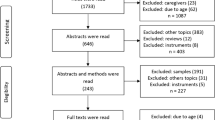

MASALA, a member study of the National Consortium on Stress, Spirituality, and Health, initially recruited participants from 2010 to 2013 (Exam 1, N = 906) in the San Francisco and greater Chicago areas for its clinical study. Participants were 40–84 years old, of South Asian descent, free of cardiovascular disease, and fluent in English, Hindi, or Urdu. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation. Participants reached the study clinic following a 12-hour fast and written informed consent was subsequently obtained by a bilingual staff. Consent forms were provided in English, Hindu, and Urdu. The original cohort (Exam 1) was interviewed a second time between 2015 and 2018 (Exam 2, N = 733) where returning cohort members completed an R/S questionnaire sponsored by the Study on Stress, Spirituality, and Health. In 2017–2018, a new MASALA recruitment effort (Exam 1A) added 258 participants to the cohort, and all individuals filled out the R/S questionnaire. In all, 989 MASALA participants completed an R/S questionnaire at Exam 2 or Exam 1A. Some individuals were excluded from these analyses, including those with missing data on key independent or dependent variables, apart from marital status (3.4% missing), where modal imputation was used. In all, 881 of 989 MASALA participants were retained for analysis. A subsample of respondents indicating belief in God (n = 813) was also analyzed to assess relationships between theist-specific measures and health outcomes. Further information on the MASALA study is available elsewhere [4].

Dependent variables

Self-rated health (SRH), assessed with a scale from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent, is among the strongest correlates of physical health, mental health, functional health, and subjective well-being [25]. Emotional functioning was measured using the three-item Mental Health Inventory index (MHI-3). The summed range was 0–15; higher scores indicate better mental health (α = 0.65) [26]. Anxiety (10 items; range 10–40; α = 0.70) and anger (10 items; range 10–40; α = 0.69) were assessed with the Spielberger scales [27].

Focal independent variables

All R/S survey items were prefaced with the following statement: “These questions are being asked of people from different religious backgrounds, and although we use the term ‘God’ in some of the questions below, please substitute your own word for ‘God’ (for example, Bhagwan, Allah, The Divine, etc.).”

Prior work supports differentiating theistic and non-theistic daily spiritual experiences (DSE) as separate indexes [28]. The non-theistic daily spiritual experience scale (four items, α = 0.78) asked how often participants experienced “a connection to all of life,” “being touched by the beauty of creation,” etc. (1 = never, 2 = once/while, 3 = some days, 4 = every day, 5 = many times/day). The theistic daily spiritual experience scale (two items, α = 0.74) asked respondents whether they “feel God’s love or care for me, through others” or “desire to be closer to God, or in union with God” (1 = definitely not true, 5 = definitely true). Belief in God (“I believe in God”) utilized the same response categories. Closeness to God (“God gives me the strength to do things,” “God loves me unconditionally,” etc.) was a five-item scale (α = 0.93) with the same coding scheme.

Gratitude has a dual meaning, both worldly and transcendent. Yet, as Emmons writes, “gratitude is a…universal religious emotion [with a] fundamental spiritual quality transcending religious traditions” [29]. Gratitude was measured as an index of two items (α = 0.74): “I have so much in life to be thankful for” and “If I had to list everything I felt grateful for, it would be a very long list” (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Frequency of praying alone and practicing yoga were coded 1 = never, 2 = several times/year, 3 = several times/month, 4 = once/week, 5 = more than once/week, 6 = once/day, and 7 = several times/day. Positive and negative religious coping asked about R/S and facing stressful events [30]. Positive coping items (eight items, α = 0.94) included “I saw my situation as part of God’s plan” and “I trusted God would be by my side,” among others. Negative coping items (six items, α = 0.83) included “I wondered what I did for God to punish me” and “I wondered if God allowed this to happen because of my wrongdoings,” among others. Response options were 1 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite a bit, and 4 = a great deal. Divine hope was assessed using two de novo items (α = 0.87) developed through focus groups conducted with ethnically diverse individuals in the Boston area: “I felt hopeful that God would help me get through one day at a time” and “I looked to my faith in God for hope about the future.” R/S struggles used two items (α = .84) to examine doubt in response to stress with prompts “I felt confused about my religious or spiritual beliefs” and “I felt troubled by doubts or questions about my religion or spirituality” [31]. Response categories were identical to religious coping and divine hope.

Covariates

Binary control variables included sex, full-time employment, home ownership, marital status, and anti-depressant medication use. Additional controls included age, education, percent life in the US, alcohol consumption, and language spoken at home (1 = only South Asian language, 2 = South Asian language more than English, 3 = both equally, 4 = English more than South Asian language, 5 = only English). R/S controls included religious service attendance (1 = never to 6 = several times/week) and South Asian religious traditions categorized as Hindu, Muslim, Jain, Sikh, other (Buddhist, Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, etc.), multiple religions, and none. The “none” category included atheists, agnostics, and non-affiliated individuals.

Analytic strategy

Descriptive statistics were examined for all study variables. Since outcomes were continuous and normally distributed, general linear models with robust standard errors were fitted using PROC GENMOD in SAS 9.4.Footnote 1 Five R/S items asked of the full sample were modeled with all respondents. Six theistic R/S items were modeled only with those respondents reporting belief in God. While it would have been possible to model all 11 R/S items in the theistic sample, this presented collinearity concerns and increased the chance of committing a type I error. After making this choice, the selected R/S items were examined independently and collectively in each sample, controlling for religious tradition and religious attendance. Collective models were reported to facilitate comparison among R/S variables. Significant independent associations were also indicated, with coefficients and p values reported in the results section. Supplemental analyses using COLLIN and VIF commands did not indicate a disrupting presence of multicollinearity after division of R/S variables across the full and theistic samples.Footnote 2

Results

Descriptive data are reported in Table 1 for the full sample, as well as the subset of participants who endorsed belief in God (i.e., theistic sample). Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 report linear regression results for SRH, emotional functioning, anxiety, and anger, respectively.Footnote 3

Self-rated health (SRH)

Frequency of yoga practice (b = .052, p < .001), feelings of gratitude (b = .118, p = .018), and non-theistic DSE (b = .168, p < .001) were associated with higher levels of SRH in the full sample. Closeness to God (b = .154, p = .025) and positive religious coping (b = .091, p = .011) (single variable model) were associated with greater SRH in the theistic sample.

Emotional functioning (MHI-3)

Gratitude (b = .394, p = .012) and non-theistic DSE (b = .924, p < .001) were associated with better emotional functioning in the full sample. Closeness to God (b = .387, p = .041), positive religious coping (b = .280, p = .008) (single variable), and theistic DSE (b = .272, p = .006) (single variable) were associated with improved emotional functioning in the theistic sample. Negative religious coping (b = − .332, p = .027) (single variable) was related to lower emotional functioning in the theistic sample.

Trait anxiety

In the full sample, gratitude (b = − .778, p = .013) and non-theistic DSE (b = − 1.338, p < .001) were associated with lower levels of anxiety. In the theistic sample, negative religious coping (b = .797, p = .006) and R/S struggles (b = .672, p = .018) were associated with higher levels of anxiety.

Trait anger

Non-theistic DSE (b = − .611, p < .001) and gratitude (b = − .631, p = .008) (single variable) were associated with lower levels of anger in the full sample. R/S struggles (b = .527, p = .044) and negative religious coping (b = .797, p = .003) (single variable) were associated with higher levels in the theistic sample.

Discussion

The current study examined the relationships between an array of private religious/spiritual measures and self-rated and mental health among US South Asians. Private R/S practices and beliefs are associated with health outcomes through a variety of psychosocial resources and mechanisms [14]. R/S is thought to be a multidimensional phenomenon and the current study’s findings confirmed the multidimensionality of private R/S in relation to the health outcomes studied [23]. Non-theistic daily spiritual experiences (DSE) conferred health benefits across all outcomes. While no other R/S predictor had this level of consistency in associations with all study outcomes, several other associations were observed. Gratitude had favorable relationships with self-rated health, emotional functioning, and anxiety, and yoga was beneficially related to self-rated health. In a subsample of theistic believers, closeness to God was positively associated with self-rated health and emotional functioning. Negative patterns were also observed in relation to negative religious coping and R/S struggles, as anticipated. Specifically, negative religious coping was associated with increased anxiety and R/S struggles were linked to both trait anxiety and trait anger. To our knowledge, no previous community-based study has examined relationships between private R/S and health among US South Asians, a gap which the current article has made substantial progress in addressing.

We found that non-theistic DSE had a salutary association with all outcomes examined in this analysis: self-rated health, emotional functioning, anxiety, and anger. These results aligned with prior research that found non-theistic DSE to be associated with positive psychological outcomes. Using the 1998 and 2004 rounds of the General Social Survey, Ellison and Fan [32] found that both non-theistic and theistic DSE predicted psychological well-being but that non-theistic DSE outperformed theistic DSE. The consistent salutary role of non-theistic DSE in our results and lack of significant associations for theistic DSE pointed to the importance of measuring R/S in ways that accord with Dharmic faiths (Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, and Buddhism). Dharmic faiths express spirituality in ways that frequently transcend theistic conceptions, and measurement centered on Western or Judeo-Christian divine imagery is inadequate in studying R/S among those outside mono-theistic faiths [33]. Our results also confirmed Underwood’s assertion that researchers should consider distinguishing between non-theistic and theistic DSE in specific populations [28].

Gratitude, a “life orientation towards noticing and appreciating the positive in the world,” [34], had salutary associations in these data with self-rated health, emotional functioning, and anxiety, but not anger. Gratitude has been linked to a variety of constructs in prior research, including anger and emotional functioning in US student populations [35] and to reduced risk for internalizing and externalizing disorders in the US population [36]. While MASALA’s measure of gratitude is not specifically theistic, one study found that being grateful to God enhanced the psychological benefits of non-religious gratitude, and increasingly so as religious commitment rose [37]. Community-based studies of gratitude are rare in the literature, and the South Asian population has not been considered until now.

We found that yoga was positively associated with self-rated health. This finding differed from prior research on older adults in the National Health Interview survey which did not find statistically significant effects of mind-body therapies such as yoga on functional status or physical health-related quality of life [38]. Divergent results may be due to measurement dissimilarities and differences between yoga practiced in the general US population and yoga among South Asians. The favorable association between yoga and self-rated health in our results—but not mental health—may be due to the broad-ranging physical dimensions of health included in self-rated health and the possibility that frequent yoga practice reflected aspects of good physical health status. Whether yoga promotes physical health or physical health enables yoga practice is an important puzzle for future longitudinal research among South Asians.

Results showed that closeness to God associated with self-rated health and emotional functioning. Scholars have argued that positive associations between perceived closeness to God and health may exist because symbolic attachments to the divine provide a “safe haven” or “secure base” from which to live life with a sense of safety and security [39]. Prior research found that a secure attachment to God was inversely associated with four anxiety-related disorders in a national US sample and positively associated over time with psychological well-being in a sample of older US Blacks and whites [40, 41]. Though our results are consistent with other community-based studies, the current analysis was the first to assess closeness/attachment to God and health associations in the US South Asian population.

While various aspects of private R/S may serve as important psychosocial resources that confer health benefits, some manifestations of private R/S may also have an adverse relationship with health. Our results indicated that negative religious coping (e.g., feeling punished or abandoned by God) was associated with higher levels of anxiety. These results align with prior research that found negative religious coping associated with psychological distress in a national US sample [42]. We also found that R/S struggles (e.g., doubts and confusion about religious beliefs) were associated with higher levels of anxiety and anger. In previous research, R/S struggles were related to psychological distress in a national US sample and to depressive symptoms in a national sample of religious congregants [42, 43]. Our results were consistent with this prior research, extending it to US South Asians. Our finding that R/S struggles were associated with higher levels of trait anger is, to our knowledge, a novel contribution to extant community-based research within any US racial/ethnic group [9].

Study limitations include the following. First, because the ancillary SSSH was collected as part of MASALA’s second wave of data collection, it is not currently possible to perform prospective analyses of these R/S dynamics in relation to health outcomes within the South Asian community.Footnote 4 MASALA is currently in the process of collecting a third wave of data, which will make possible future prospective assessments of R/S and health. Second, the study’s external validity was limited by MASALA’s sampling frame, which included South Asians from the San Francisco and Chicago areas 40 years of age and older, with a disproportionate participation of high-SES Asian Indians. Study results may therefore not reflect all South Asians in the US. Third, for a portion of the sample, R/S was measured 4–5 years after anxiety and anger, potentially increasing the likelihood of a type II error. Fourth, though analyses controlled for language use at home, there remains the possibility that limited fluency in the interview languages for some participants affected responses.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first community-based study of associations between various aspects of private R/S and self-rated health and mental health in a sample of US South Asians. Our findings point to the importance of private religion and spirituality for the mental and overall health of US South Asians and suggest clinicians, public health providers, and religious care professionals may wish to consider how this population’s existing R/S beliefs and practices might inform illness prevention and treatment strategies.

Notes

Self-rated health was ordinal, but results were consistent whether ordered logit or OLS regression was used. Monte Carlo simulation suggests that ordered logit and OLS are nearly identical when the dependent variable has five to seven response categories. OLS was used here since it is more easily interpretable and because it is consistent with modeling strategies for other outcomes.

In pairwise correlations between independent variables, there were two instances in the congregation sample that reached a potentially problematic level of correlation (theistic DSE by closeness to God and positive coping by hope). We compared results in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 with ancillary models excluding the aforementioned correlated variables one by one. When excluding theistic DSE, closeness to God became nonsignificant predicting SRH (p = .11). For anxiety, when excluding closeness to God, theistic DSE became significant and when excluding theistic DSE, closeness to God became significant. Other than these exceptions, results were consistent with Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Several ordinal independent variables were assessed both categorically and linearly. Here we note differences when comparing main results with ancillary models that assessed prayer, yoga, belief in God, religious attendance, and language at home as categorical variables and education and alcohol as linear trends. Attendance is significant in Table 4 and the ancillary model finds no significant category contrasts for attendance. Whereas education contrast categories were significant in Table 4, the linear trend was marginally significant in the ancillary model predicting anxiety. One significant alcohol category contrast is seen predicting anger in Table 5, however, the linear trend was marginally significant when predicting anger. These exceptions notwithstanding, results in the ancillary analyses were in keeping those seen in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

One example of why this is important, suggested by a reviewer, is because Muslims/Hindus/Sikhs who initiate alcohol consumption may subsequently reduce private religiosity, perhaps in order to reconcile these potentially contradictory elements of their lives. Future research following individuals’ alcohol use, affiliation, and private religiosity over time can shed light on these likely reciprocal processes.

Abbreviations

- R/S:

-

Religiosity/spirituality

- US:

-

United States

- SRH:

-

Self-rated health

- DSE:

-

Daily spiritual experiences

- MASALA:

-

Mediators of Atherosclerosis among South Asians living in America

- SSSH:

-

Study on Stress, Spirituality, and Health

References

Chaves, M. A. (2017). American religion: Contemporary trends (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Zimmer, Z., Jagger, C., Chiu, C.-T., et al. (2016). Spirituality, religiosity, aging and health in global perspective: A review. SSM-Population Health,2, 373–381.

Schieman, S., Bierman, A., & Ellison, C. G. (2013). Religion and mental health. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 457–478). New York: Springer.

Kanaya, A. M., Kandula, N., Herrington, D., et al. (2013). Mediators of atherosclerosis in South Asians living in America (MASALA) study: Objectives, methods, and cohort description. Clinical Cardiology,36, 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22219.

Diwan, S., Jonnalagadda, S. S., & Balaswamy, S. (2004). Resources predicting positive and negative affect during the experience of stress: A study of older Asian Indian immigrants in the United States. The Gerontologist,44, 605–614.

Stroope, S., Kent, B. V., Zhang, Y., et al. (2019). Mental health and self-rated health among US South Asians: The role of religious group involvement. Ethnicity Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2019.1661358.

United States Census Bureau. Population groups summary file 1. 2010. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/press-kits/summary-file-1.html

Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hill, T. D., & Mannheimer, A. H. (2014). Mental health and religion. In W. C. Cockerham, R. Dingwall, & S. R. Quah (Eds.), The wiley blackwell encyclopedia of health, illness, behavior, and society (pp. 1522–1525). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Stroope, S., Draper, S., & Whitehead, A. L. (2013). Images of a loving god and sense of meaning in life. Social Indicators Research,111, 25–44.

Schieman, S., Pudrovska, T., Pearlin, L. I., et al. (2006). The sense of divine control and psychological distress: Variations across race and socioeconomic status. Journal of Scientific Study of Religion,45, 529–549.

Krause, N. (2005). God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging,27, 136–164.

Kurien, P. A. (2007). A place at the multicultural table: The development of an American Hinduism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). Religion and health: A synthesis. In M. Balboni & J. Peteet (Eds.), Spirituality and religion within the culture of medicine: From evidence to practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Levin, J. (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Krause, N., & Bastida, E. (2011). Religion, suffering, and self-rated health among older Mexican Americans. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,66B, 207–216.

Sternthal, M. J., Williams, D. R., Musick, M. A., et al. (2012). Religious practices, beliefs, and mental health: Variations across ethnicity. Ethnicity & Health,17, 171–185.

Diwan, S., & Jonnalagadda, S. S. (2002). Social integration and health among Asian Indian immigrants in the United States. Journal of Gerontological Social Work,36, 45–62.

Min, P. G. (2010). Preserving ethnicity through religion in America: Korean protestants and Indian Hindus across generations. New York: NYU Press.

Sciupac EP. U.S. Muslims are religiously observant, but open to multiple interpretations os Islam. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center 2017. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/28/u-s-muslims-are-religiously-observant-but-open-to-multiple-interpretations-of-islam/

Winchester, D. (2008). Embodying the faith: Religious practice and the making of a Muslim moral habitus. Social Forces,86, 1753–1780.

Afzal, A. (2014). Lone star muslims: Transnational lives and the South Asian experience in Texas. New York: NYU Press.

Idler, E. L., Musick, M. A., Ellison, C. G., et al. (2003). Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research conceptual background and findings from the 1998 general social survey. Research on Aging,25, 327–365.

Zinnbauer, B. J., Pargament, K. I., Cole, B., et al. (1997). Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal of Scientific Study of Religion,36, 549–564.

Schnittker, J., & Bacak, V. (2014). The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLoS ONE,9, e84933.

Veit, C. T., & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,51, 730.

Spielberger, C. D. (1980). Preliminary manual for the state-trait anger scale (STAS). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press Inc.

Underwood, L. (2006). Ordinary spiritual experience: Qualitative research, interpretive guidelines, and population distribution for the daily spiritual experience scale. Archive for the Psychology of Religion,28, 181–218.

Emmons, R. A. (2012). Queen of the virtues? Gratitude as human strength. Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry,32, 49–62.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology,56, 519–543.

Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Grubbs, J. B., et al. (2014). The religious and spiritual struggles scale: development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality,6, 208.

Ellison, C. G., & Fan, D. (2008). Daily spiritual experiences and psychological well-being among US adults. Social Indicators Research,88, 247–271.

Traphagan, J. W. (2005). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research in cross-cultural perspective. Research on Aging,27, 387–419.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Reveiw,30, 890–905.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2009). Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the Big Five facets. Personality and Individual Differences,46, 443–447.

Kendler, K. S., Liu, X.-Q., Gardner, C. O., et al. (2003). Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry,160, 496–503.

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Cohen, A. B., et al. (2011). Grateful to God or just plain grateful? A comparison of religious and general gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology,6, 389–396.

Nguyen, H. T., Grzywacz, J. G., Lang, W., et al. (2010). Effects of complementary therapy on health in a National U.S. sample of older adults. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine,16, 701–706.

Granqvist, P., & Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2013). Religion, spirituality, and attachment. In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality: Context, theory, and research (pp. 129–155). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Ellison, C. G., Bradshaw, M., Flannelly, K. J., et al. (2014). Prayer, attachment to god, and symptoms of anxiety-related disorders among U.S Adults. Sociology of Religion,75, 208–233.

Kent, B. V., Bradshaw, M., & Uecker, J. E. (2018). Forgiveness, attachment to God, and mental health outcomes in older US adults: A longitudinal study. Research on Aging,40, 456–479.

Ellison, C. G., & Lee, J. (2010). Spiritual struggles and psychological distress: is there a dark side of religion? Social Indicators Research,98, 501–517.

Krause, N., & Wulff, K. M. (2004). Religious doubt and health: Exploring the potential dark side of religion. Sociology of Religion,65, 35–56.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editors and reviewers for their service and Meghan Podolsky for research assistance.

Funding

This analysis was supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation (Grant #59607) and the Study on Stress, Spirituality, and Health. The MASALA Study was supported by NIH Grants 1R01HL093009, 2R01HL093009, R01HL120725, UL1RR024131, UL1TR001872, and P30DK098722.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kent, B.V., Stroope, S., Kanaya, A.M. et al. Private religion/spirituality, self-rated health, and mental health among US South Asians. Qual Life Res 29, 495–504 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02321-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02321-7