Abstract

Purpose

We examined if child maltreatment (CM) is associated with worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in midlife women and if the association is mediated by psychosocial factors.

Methods

A total of 443 women were enrolled in the Pittsburgh site of the longitudinal Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation-Mental Health Study. The analytic sample included 338 women who completed the SF-36 and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Generalized linear regression was used to assess the association between CM and two HRQoL component scores. Structural nested mean models were used to evaluate the contribution of each psychosocial mediator (lifetime psychiatric history, depressive symptoms, sleep problems, very upsetting life events, low social support) to the association.

Results

Thirty-eight percent of women reported CM. The mean mental (MCS) and physical (PCS) SF-36 component scores were 2.3 points (95% CI − 4.3, − 0.3) and 2.5 points (95% CI − 4.5, − 0.6) lower, respectively, in women with any CM than in those without. When number of CM types increased (0, 1, 2, 3+ types), group mean scores decreased in MCS (52, 51, 48, 47, respectively; p < .01) and PCS (52, 52, 49, 49, respectively; p = .03). In separate mediation analyses, depressive symptoms, very upsetting life events, or low social support, reduced these differences in MCS, but not PCS.

Conclusions

CM is a social determinant of midlife HRQoL in women. The relationship between CM and MCS was partially explained by psychosocial mediators. It is important to increase awareness among health professionals that a woman’s midlife well-being may be influenced by early-life adversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional evaluation of physical, emotional, and social/role functioning [1], and is an important outcome in the evaluation of disability and disease progression. Although HRQoL typically reflects aspects of life most likely to be affected by changes in health status, it is also related to psychosocial status and proximal characteristics of the environment such as stress, financial strain, and social supports, and may be influenced by distal factors like child maltreatment (CM), which includes abuse (acts of commission) and/or neglect (acts of omission) by caregivers before 18 years of age [2]. CM has been viewed as a life-course social determinant of adult health with substantial socioeconomic cost [2]. Importantly, previous studies showed that female adult survivors are more vulnerable to the long-lasting burden of mental health problems from abuse or neglect than males [3, 4].

It is not clear whether CM is associated with midlife HRQoL in general populations. Two studies from the Netherlands [5, 6] and the USA [7] identified negative associations between CM and HRQoL in community or population samples [8]. Most research to date is based on clinical or health-insured samples [8,9,10,11,12,13,14], which may limit generalizability. Furthermore, studies [5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, 16] often used standard regression methods, which do not properly account for mediator–outcome confounders affected by CM exposure [17], to examine possible psychosocial mediators (e.g., psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, depressive symptoms, social support, life events) of the relationship between CM and HRQoL.

We sought to address the limitations in the previous literature using extensive demographic, behavioral, and HRQoL data collected from a community-based cohort of 443 women recruited into the Pittsburgh site of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Our specific aims were to (1) assess if women with CM have worse midlife HRQoL than women without CM and if this is the case for both black and white women and (2) evaluate whether psychosocial factors previously shown to be associated with CM (lifetime psychiatric history, depressive symptoms, sleep problems, very upsetting life events, or low social support) individually explained the relationship between CM and two dimensions of HRQoL: mental component score (MCS) and physical component score (PCS), using state of the art analytic approaches to test for mediation.

Methods

Study population

We used data from SWAN, a multi-site, community-based, cohort study that aimed to investigate middle-aged women’s mental and physical health during and after the menopausal transition. A detailed explanation of the SWAN study design is available in a previous paper [18]. Briefly, eligible women recruited in seven cities in the U.S. between 1996 and 1997 were 42–52 years, with at least one menstrual period in the previous 3 months, not currently using exogenous hormones, no surgical removal of the uterus and/or both ovaries, not pregnant, and not breastfeeding. Each site of SWAN recruited approximately 450 women that included white women and a prespecified minority group of women (African American, Hispanic, Japanese, or Chinese). Random digit dialing and a voter registration list were used as sampling techniques for the recruitment at the Pittsburgh SWAN site. Our investigation is based on 443 women who also participated in the Mental Health ancillary study (MHS) at the Pittsburgh site. Women were followed annually to provide biological specimens and to complete extensive questionnaires about physical, psychosocial, lifestyle, and psychological factors. Women in SWAN-MHS also completed the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnosis (SCID) of DSM-IV Axis I Disorders [19] at baseline and each annual follow-up visit. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. For inclusion in the current analysis, completion of the full Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form 36 (SF-36) [20] at Visit 6 (6 years after the study entry, 2002–2003) or Visit 8 (2004–2005) and completion of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [21] at Visit 8 were required.

Measures

Exposure (X). CM from early childhood through age 18 was retrospectively ascertained by the CTQ at Visit 8 [21]. Items were summed to derive scores on five types of CM. The summed scores were classified as scoring positive for each type of CM using previously validated clinical cut-offs as follows: emotional abuse (≥ 10), physical abuse (≥ 8), sexual abuse (≥ 8), physical neglect (≥ 8), and emotional neglect (≥ 15) [14]. Each CM type was categorized as maltreated (moderate to severe) and non-maltreated (none to just below the thresholds). The CTQ has high test–retest reliability and strong convergent validity with therapists’ ratings and clinical interviews [14, 22]. CM types above these clinical cut-offs were counted to indicate the total number of CM types ranging from 1 to 5. Exposure to different types of CM was also combined into five mutually exclusive CM subgroups: (1) emotional abuse and/or physical abuse, (2) emotional neglect and/or physical neglect, (3) sexual abuse only, (4) abuse and neglect, and (5) sexual abuse along with other CM types.

Outcome (Y). Midlife HRQoL was assessed by the SF-36, a generic measure of health profiles in physical health, mental health, and social functioning [20] at Visit 6 (or 8 if not completed at Visit 6). The SF-36 is an established HRQoL questionnaire with high reliability and validity and it has been widely used in epidemiological studies [20]. The SF-36 includes eight subdomains and two component T-scores: MCS and PCS. MCS and PCS were calculated by standardizing each of the eight SF-36 scales and transforming the aggregate score to a norm-based score with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 in the 1998 general U.S. population [23]. Higher scores indicate better mental or physical health status. MCS or PCS below 50 is considered below the average in the general U.S. population.

Mediators (M). Data for all psychosocial mediators were from Visit 6 or 8. Lifetime and current psychiatric history were initially diagnosed at study entry and at each follow-up by trained mental health clinicians using the SCID [19], with very good reliability for lifetime depressive and anxiety disorders (kappa = 0.81–0.82) [24]. Lifetime psychiatric disorders were defined as occurring up to Visit 6 or 8 for any of the following disorders: major depression; minor depression; any anxiety disorder; alcohol use disorder, abuse, or dependence; and non-alcohol use disorder, abuse, or dependence. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [25] at baseline and each follow-up visit. The CES-D is a widely used measure of depressive symptom levels with well-established reliability, and a cut-off score ≥ 16 is used as an indicator of potential clinical depression [25]. Sleep problems were self-reported by women and were defined as having at least three nights of at least one of the three sleep problems (i.e., sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, early morning awakening) in each of the past 2 weeks. Very upsetting life events were assessed by the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview scale [26], modified to include events relevant to midlife women or those living in low socioeconomic environments. “Very upsetting” or “very upsetting and still upsetting” life events since the last study visit were totaled and categorized as 1 or more versus none. Instrumental and emotional social support was assessed by the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey [27]. Participants were asked how often each of four kinds of support (two instrumental and two emotional) is available when they need it. The total score ranged from 0 to 16. A score below the 25th percentile (< 12) was defined as low social support since a standard cut-point is not available and the distribution of scores is highly skewed.

Overview of measures and models

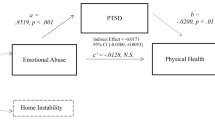

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships among CM (X), potential psychosocial mediators (M), midlife HRQoL outcomes (Y), exposure-outcome confounders (CXY), mediator–outcome confounders (LMY), and other potential unmeasured confounders (U). Age at baseline, race/ethnicity, and childhood socioeconomic circumstances (SES) were considered as a vector of CXY confounders, common correlates of CM exposure and HRQoL outcomes. Race/ethnicity was also considered as a potential effect modifier of a CM and HRQoL relationship. A vector of adulthood confounders (LMY), common correlates of the mediators and HRQoL outcomes, included education, marital status, financial strain, lifestyle behaviors, BMI, the number of lifetime medical conditions, menopausal status, vasomotor symptoms, use of exogenous hormones, trait anger and anxiety, and lifetime treatment for emotional problems. Due to the long-term effect of CM, several factors among the adulthood confounders LMY (i.e., education, financial strain, lifestyle behaviors, BMI, trait anger and anxiety, treatment for emotional problems) are associated with CM and could be considered as exposure-induced mediator–outcome confounders [17]. These confounders are specified and described below.

Analytic diagram of the relationship between CM (X), potential psychosocial mediators (M), and HRQoL outcomes (Y). Mediator–outcome confounders (LMY) are associated with the early-life exposure X. If conditioning on LMY by standard regression method, collider bias will be induced along the path of X → LMY ← U → Y, and association of interest will be blocked through the path of X→ LMY → Y. Research of interest (counterfactual disparity measure) is the extent to which (dashed arrows) CM (X) is associated with HRQoL after the mediator’s effect is removed

Exposure-outcome confounders (CXY). CXY includes age, race/ethnicity, and childhood socioeconomic status (SES). Childhood SES from early childhood through age 18 was self-reported at Visit 7, based on questions about maternal and paternal education, and childhood financial circumstances such as whether the family owned a car, a house, or ever received public assistance. Previous work in SWAN has reported that childhood SES as measured at two separate visits was highly concordant [28].

Mediator–outcome confounders (LMY ). LMY confounders were collected at SWAN baseline or the Visit 6/8. Adulthood sociodemographic factors included educational attainment, marital status, and financial strain. Lifestyle behavioral variables (current smoking, weekly alcohol consumption, physical activity) and body mass index (BMI) were included as LMY confounders. The number of lifetime medical conditions were summed from the questionnaire inquiring about 12 prespecified medical conditions. Menopausal status at the time of the midlife HRQoL assessment was categorized based on menstrual bleeding patterns in the previous 12 months [29]. The presence of vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats) in the past 2 weeks was ascertained as part of a symptom checklist. Ever use of hormone therapy since the SWAN baseline and lifetime treatment for emotional problems were self-reported. Trait anger and anxiety were assessed by the Spielberger Trait Anger and Anxiety Scales [30].

Statistical analysis

Variable values were compared between those with and without any CM exposure using Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. To calculate the effect sizes for group differences, we used the reference norm SD = 9.47 for MCS and SD = 10.82 for PCS from the normative U.S. population of women aged 45–54 years [23]. Effect sizes were calculated as group differences in HRQoL scores divided by SDnorm [31]. We defined group differences in MCS or PCS with effect sizes < 0.2 as small and not clinically meaningful, effect sizes 0.2–0.5 as moderate and potentially meaningful, and effect sizes > 0.5 as large and clinically meaningful [32].

Overall associations between CM and HRQoL. We used generalized linear models to evaluate CM in several different ways in eight separate models: any CM (maltreated versus non-maltreated) as the main predictor, five individual types of CM not mutually exclusive, a total number of CM (0, 1, 2 and more), and mutually exclusive combined CM subgroups adjusting for age, race, and childhood SES. To assess whether the relationship between CM and HRQoL was the same for blacks and whites, the product of any CM and race and the products of each CM type and race were added in separate main effect models. As with most studies, we did not have sufficient power to statistically detect effect modification. We defined effect modification as present if the magnitude of the beta coefficient of CM on HRQoL was changed by more than ± 2 points after adding the interaction product term to the outcome model. A two points difference of HRQoL was determined by the meaningful moderate effect size (ES = 0.2) times the standard deviation (SD = 10) of MCS and PCS (i.e., moderate effect size × SD = 0.2 × 10 = 2).

Mediation analysis. We used structural nested mean models (SNMMs) estimated via doubly robust g-estimation to quantify the extent to which CM would be associated with HRQoL if each mediator were set to a specific value uniformly in the population (See Online Appendix) [33]. Unlike commonly used regression-based approaches, this method properly accounts for confounders of the mediator–outcome relation that are also associated with childhood maltreatment (LMY, as depicted in Fig. 1). If conditioning on LMY by standard regression method, collider bias will be induced along the path of X → LMY ← U → Y, and association of interest will be blocked through the path of X → LMY → Y. The main object we estimated was

which we refer to as the counterfactual disparity measure. This object can be interpreted as the magnitude of the association between any CM and HRQoL that would remain (dashed arrows in Fig. 1) if the mediators in our study were held fixed at some referent value. The proportion explained by these mediators was calculated as

Detailed steps of our mediation analysis are illustrated in the Online Appendix. SAS 9.4 was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Of the 443 participants in SWAN-MHS, 338 women met the two inclusion criteria (See Online Appendix Fig. 1) for the current analysis: completion of first full SF-36 at Visit 6 or Visit 8 and CTQ at visit 8. Mean age was 52 years and 33% of the women in the sample were Black (Table 1). Thirty-eight percent of the participants reported at least one type of CM and 20% reported two or more types of CM before 18 years of age. Based on subgroups of CM experience, 11% of women experienced abuse, 4% neglect, 5% sexual abuse, 8% abuse and neglect, and 10% sexual abuse along with other CM types. A total of 200 (59%) women had a lifetime psychiatric history. High depressive symptoms were observed in 15% of women, sleep problems in 42%, at least one very upsetting life event in 47%, and low social support in 17% (Table 1).

Mean (SD) midlife HRQoL scores were 51.0 (8.8) for MCS and 51.5 (9.1) for PCS. Both mean MCS and PCS were above the average of the U.S. general population (better health) (23). The lowest MCS was reported by women with child sexual abuse [mean (SD) = 47.6(10)], and the lowest PCS by women with emotional neglect [mean (SD) = 44.8(11.8)]. When total number of CM types increased (0, 1, 2, 3 + types), group mean scores decreased in MCS (52, 51, 48, 47, respectively; p = .001) and PCS (52, 52, 49, 49, respectively; p = .025). Mean MCS and PCS were both lower than the norm of 50 among women with child abuse and neglect or child sexual abuse along with other CM types.

The adjusted associations between CM and HRQoL after accounting for age, race, and childhood SES are shown in Table 2. Mean MCS was 2.3 points lower (95% CI − 4.3, − 0.3) and PCS was 2.5 points lower (95% CI − 4.5, − 0.6) in women with any CM compared to those without. MCS was 4.1 points lower (95% CI − 7.3, − 1.0) in women with child sexual abuse compared to women without child sexual abuse. Mean PCS was lower in women with child physical abuse [β (95% CI) − 3.8 (− 6.9, − 0.6)] and child emotional neglect [− 6.8 (− 11.3, − 2.4)] than their counterparts without either. Women with two or more types of CM had lower MCS [− 3.6 (− 6.4, − 0.8)] and PCS [− 3.5 (− 6.1, − 0.8)] than non-maltreated women. Among CM subgroups, MCS was lower in women with a history of child sexual abuse along with other CM types [− 5.5 (− 9.7, − 1.2)] relative to those without any CM. PCS was significantly lower among women with a history of child abuse and neglect [− 3.1 (− 6.2, − 0.1)] than non-maltreated women.

Results for the effect modification of CM by race indicated that the magnitude of physical abuse on PCS differed more than 2 points by racial groups after adding the interaction term. White women with child physical abuse reported 5.7 points significantly lower PCS (95% CI − 9.7, − 1.7) than white women without child physical abuse. PCS was not significantly different in black women with child physical abuse [1.0 (− 3.1, 5.1)] than black women without child physical abuse.

Using SNMMs, we evaluated the extent to which each psychosocial mediator explained the relation between CM and HRQoL, after adjusting for two sets of confounders CXY and LMY (Table 3b). After accounting for the contribution of psychosocial factors, the difference in MCS scores between maltreated and non-maltreated women decreased from − 2.4 (95% CI − 4.5, − 0.4) to − 1.6, (95% CI − 3.4, 0.2), − 1.9 (95% CI − 3.9, 0.1), or − 1.7 (95% CI − 3.7, 0.3) in separate mediation models with high depressive symptoms, very upsetting life events, or low social support, respectively. In contrast, the association between any CM and lower MCS was not greatly affected by lifetime psychiatric history or sleep problems. Psychosocial mediators did not influence the association between CM and PCS.

Discussion

In this community-based cohort, CM was a robust risk factor for lower midlife mental and physical HRQoL in women, after adjusting for childhood SES variables, race, and age. The association between CM and mental HRQoL was partially explained by the proximal adulthood psychosocial mediators: depressive symptoms, very upsetting life events, or low social support.

The overall prevalence of CM in our study was similar or slightly lower than the rates found in previously published studies of females and males which ranged from 34 to 48% [10, 14, 34, 35]. The prevalence rates of CM subtypes in this study (see Table 1) were comparable to research studies in the U.S. using the CTQ. The rate of emotional neglect in the present study (8%) was lower than the rates found in U.S. studies by Walker et al. (21%) and Fagundes et al. (12%) [14, 34], while the rates of physical neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, or sexual abuse were similar to the rates observed in these studies [14, 34]. In addition, a meta-analysis with 59,500 individuals from multiple countries reported that the average combined prevalence of emotional neglect was 18% and that for physical neglect was 16% [36]. The prevalence of any psychiatric disorders in our study (59%) was slightly higher compared to the prevalence in women (50%) in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [37].

Examination of each type of CM showed child sexual abuse had a moderate relationship with lower MCS, child physical abuse had a moderate association with lower PCS, and child emotional neglect had a strong and clinically meaningful relationship with lower PCS. Afifi et al. found that each type of CM was significantly associated with lower scores in MCS and PCS in a large Dutch population sample of 7076 males and females [5]. However, a large U.S. insurance-based study with men and women found that child emotional neglect had the strongest influence on reduced well-being, followed by child sexual abuse and child physical abuse [10]. Although these studies did not report results separately for men and women, our results are similar to the previous U.S. findings overall.

Our study confirmed that effect sizes increased as the total number of CM types increased, as reported previously [5, 9, 14, 15]. We found abuse and neglect had a moderate association with lower PCS, and sexual abuse along with other CM types had a strong association with lower MCS. Studies investigating associations between child sexual abuse and HRQoL in women have reported small to moderate effect sizes ranging from − 0.20 to − 0.36 [5, 8, 9, 12, 14]. We further distinguished the child sexual abuse only burden on mental HRQoL (effect size = − 0.25) and sexual abuse along with other CM types (effect size = − 0.58). Women with the latter exposures experienced a greater clinical burden on their mental HRQoL.

Plausible mechanisms underlying the relationship between any CM and HRQoL were also investigated in the current study. When accounting for each mediator in separate models, the greatest proportion of the relation between CM and MCS was explained by depressive symptoms (35%), followed by low social support (28%), and very upsetting life events (21%). In contrast, the association between any CM and physical HRQoL was not explained by adult psychosocial factors, but a notable proportion was explained by sleep problems (11%). Interventions targeting these modifiable factors may prevent or alleviate the impairment of midlife HRQoL. However, adult psychosocial factors only partially explained the relationship between CM and HRQoL. These findings suggest that CM has a robust and direct association with lower midlife HRQoL even after adjusting for childhood SES, education, marital status, adult financial strain, and other physical and mental health confounders, emphasizing the importance of interventions earlier in life. There has been a surge of scientific evidence providing both psychosocial and biological explanations for the relationship of child abuse and neglect to reduced quality of interpersonal relationships and self-esteem, increased risk of exposure to life stressors, and altered brain structure, activity, and functioning [38, 39]. The neurobiological alterations associated with CM may affect stress responses and result in difficulties with emotional regulation of arousing situations, behavioral development, executive functions, and delay of learning [40].

Several limitations should be noted. One, CM was assessed retrospectively by the self-report CTQ and the duration or age of CM onset was not assessed. Self-report assessment may potentially result in recall bias and misclassification of the exposure. However, previous evidence showed that the CTQ has high test–retest reliability and strong convergent validity with therapists’ ratings and clinical interviews [14, 22]. Two, potential unmeasured confounders (e.g., parental CM experiences, parental psychiatric history, adulthood experiences of abuse) were not assessed and therefore were not accounted for in our analyses. However, we were able to adjust for many variables (i.e., childhood SES, medical conditions, lifetime medical treatment for emotional problems) that have not yet been considered in prior work. Three, there could be bias due to left truncation in our study. Left truncation occurs when women who meet eligibility criteria at the time of study recruitment do not contribute observable data. This could potentially lead to bias if, for example, women with the most severe CM were not eligible for enrollment in the study because they had higher death or drop-out rates prior to study start. Our analysis required that women attend SWAN Visit 6 or Visit 8. Although women participating in the current study did not differ substantially from the original SWAN sample on age and race/ethnicity, they were more likely to have a college education or higher, and were more likely to be married or living with someone as if married. Four, we did not have sufficient statistical power to examine multiple mediators in one model due to the relatively small sample size. However, the counterfactual disparity measure of CM on HRQoL accounting for each psychosocial mediator may provide some guidance for targets of future intervention studies to enhance HRQoL in middle-aged women with a CM history.

Our study has many strengths. First, SWAN-MHS is a community-based cohort sample with better generalizability of results compared with clinical samples. Second, the measurements of CM exposure and HRQoL were obtained by standardized instruments. Third, lifetime psychiatric disorders were ascertained by the SCID, a semi-structured psychiatric interview, which has substantial reliability for lifetime depressive and anxiety disorders [24]. Fourth, since many adulthood factors were affected by CM exposures, standard regression methods were not valid because of the complex feedback relations between CM, mediator–outcome confounders, and the mediators under study. SNMMs are an appropriate modeling strategy that can account for such complex across the life-course [33].

In conclusion, CM is a robust social determinant of midlife mental and physical HRQoL in women. Adulthood psychosocial factors (depressive symptoms, very upsetting life events, low social support) partially mediate the association between CM and mental HRQoL, but not physical HRQoL in this study. These modifiable factors may be targeted for future intervention studies to improve well-being in midlife victims of CM by promoting a broad spectrum of protective factors such as strengthening the social support network, reducing depressive symptoms, or alleviating sleep problems. Findings from our study provide knowledge to advance research and increase our ability to mitigate the negative impact of early adverse exposures on later HRQoL. It is important to increase the awareness among health professionals that an individual’s midlife well-being may be influenced by early-life adversity.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale

- CTQ:

-

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

- CM:

-

Child maltreatment

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- MCS:

-

Mental component score

- PCS:

-

Physical component score

- SCID:

-

Structured clinical interview for the diagnosis of DSM-IV axis 1 disorders

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SF-36:

-

Medical outcomes survey short form 36

- SNMM:

-

Structural nested mean model

- SWAN-MHS:

-

Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation-Mental Health Study

References

Fayers, P. M., & Machin, D. (2016). Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes (3rd ed.). Chichester: Wiley.

Greenfield, E. A. (2010). Child abuse as a life-course social determinant of adult health. Maturitas, 66(1), 51–55.

Cutler, S. E., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Accounting for sex differences in depression through female victimization: Childhood sexual abuse. Sex Roles, 24(7), 425–438.

Weiss, E. L., Longhurst, J. G., & Mazure, C. M. (1999). Childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for depression in women: Psychosocial and neurobiological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(6), 816–828.

Afifi, T. O., Enns, M. W., Cox, B. J., de Graaf, R., ten Have, M., & Sareen, J. (2007). Child abuse and health-related quality of life in adulthood. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(10), 797–804.

Cuijpers, P., Smit, F., Unger, F., Stikkelbroek, Y., ten Have, M., & de Graaf, R. (2011). The disease burden of childhood adversities in adults: A population-based study. Child Abuse Neglect, 35(11), 937–945.

Rikhye, K., Tyrka, A. R., Kelly, M. M., Gagne, G. G. Jr., Mello, A. F., Mello, M. F., et al. (2008). Interplay between childhood maltreatment, parental bonding, and gender effects: Impact on quality of life. Child Abuse Neglect, 32(1), 19–34.

Weber, S., Jud, A., & Landolt, M. A. (2016). Quality of life in maltreated children and adult survivors of child maltreatment: A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 25(2), 237–255.

Bonomi, A. E., Cannon, E. A., Anderson, M. L., Rivara, F. P., & Thompson, R. S. (2008). Association between self-reported health and physical and/or sexual abuse experienced before age 18. Child Abuse Neglect, 32(7), 693–701.

Corso, P. S., Edwards, V. J., Fang, X., & Mercy, J. A. (2008). Health-related quality of life among adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 1094–1100.

Dickinson, L. M., deGruy, F. V., Dickinson, W. P., & Candib, L. M. (1999). Health-related quality of life and symptom profiles of female survivors of sexual abuse. Archives of Family Medicine, 8(1), 35–43.

Draper, B., Pfaff, J. J., Pirkis, J., Snowdon, J., Lautenschlager, N. T., Wilson, I., et al. (2008). Long-term effects of childhood abuse on the quality of life and health of older people: Results from the Depression and Early Prevention of Suicide in General Practice Project. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 56(2), 262–271.

Evren, C., Sar, V., Dalbudak, E., Cetin, R., Durkaya, M., Evren, B., et al. (2011). Lifetime PTSD and quality of life among alcohol-dependent men: Impact of childhood emotional abuse and dissociation. Psychiatry Research, 186(1), 85–90.

Walker, E. A., Gelfand, A., Katon, W. J., Koss, M. P., Von Korff, M., Bernstein, D., et al. (1999). Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. American Journal of Medicine, 107(4), 332–339.

Agorastos, A., Pittman, J. O., Angkaw, A. C., Nievergelt, C. M., Hansen, C. J., Aversa, L. H., et al. (2014). The cumulative effect of different childhood trauma types on self-reported symptoms of adult male depression and PTSD, substance abuse and health-related quality of life in a large active-duty military cohort. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 58, 46–54.

Aversa, L. H., Lemmer, J., Nunnink, S., McLay, R. N., & Baker, D. G. (2014). Impact of childhood maltreatment on physical health-related quality of life in U.S. active duty military personnel and combat veterans. Child Abuse Neglect, 38(8), 1382–1388.

Vanderweele, T. J., Vansteelandt, S., & Robins, J. M. (2014). Effect decomposition in the presence of an exposure-induced mediator-outcome confounder. Epidemiology, 25(2), 300–306.

Sowers, M., Crawford, S., Sternfeld, B., Morganstein, D., Gold, E., Greendale, G., et al. (2000) SWAN: A multicenter, multiethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: R. A. Lobo, J. Kelsey, & R. Marcus, Menopause: Biology and pathobiology (pp. 175–188). New York: Academic Press.

Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Gibbon, M., & First, M. B. (1992). The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49(8), 624–629.

Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M. A., & Gandek, B. G. (1993). SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: Health Institute, Boston New England Medical Centre.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Neglect, 27(2), 169–190.

Bernstein, D. P., Fink, L., Handelsman, L., Foote, J., Lovejoy, M., Wenzel, K., et al. (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(8), 1132–1136.

Ware, J. E. (1994). SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. Boston: Health Institute, New England Medical Center.

Bromberger, J. T., Kravitz, H. M., Chang, Y. F., Cyranowski, J. M., Brown, C., & Matthews, K. A. (2011). Major depression during and after the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychological Medicine, 41(9), 1879–1888.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Dohrenwend, B. S., Askenasy, A. R., Krasnoff, L., & Bruce, P. (1978). Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: The PERI Life Events Scale. Journal of Health Social Behaviour, 19(2), 205–229.

Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science Medicine, 32(6), 705–714.

Montez, J. K., Bromberger, J. T., Harlow, S. D., Kravitz, H. M., & Matthews, K. A. (2016). Life-course Socioeconomic Status and Metabolic Syndrome Among Midlife Women. Journal of Gerontology B Psychological Science Social Science, 71(6), 1097–1107.

World Health Organization. (1996). Research on the menopause in the 1990s: Report of a WHO scientific group. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO).

Spielberger, C. D., & Reheiser, E. C. (2009). Assessment of emotions: Anxiety, anger, depression, and curiosity. Applied Psychology Health Well Being, 1(3), 271–302.

Yost, K. J., Haan, M. N., Levine, R. A., & Gold, E. B. (2005). Comparing SF-36 scores across three groups of women with different health profiles. Quality Life Research, 14(5), 1251–1261.

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A., & Wyrwich, K. W. (2003). Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care, 41(5), 582–592.

Naimi, A. I., Schnitzer, M. E., Moodie, E. E., & Bodnar, L. M. (2016). Mediation analysis for health disparities research. American Journal of Epidemiology, 184(4), 315–324.

Fagundes, C. P., Lindgren, M. E., Shapiro, C. L., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2012). Child maltreatment and breast cancer survivors: Social support makes a difference for quality of life, fatigue, and cancer stress. European Journal of Cancer, 48(5), 728–736.

Witt, A., Brown, R. C., Plener, P. L., Brähler, E., & Fegert, J. M. (2017). Child maltreatment in Germany: Prevalence rates in the general population. Child Adolescent Psychiatry Mental Health, 11, 47.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2013). The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 345–355.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627.

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” System: How early experiences shape the development of executive function: Working paper no. 11. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Published February 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/How-Early-Experiences-Shape-the-Development-of-Executive-Function.pdf

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2015). Understanding the effects of maltreatment on brain development. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Published April 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2016. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/brain_development.pdf.

Glaser, D. (2000). Child abuse and neglect and the brain-a review. Journal of Child Psychology Psychiatry, 41(1), 97–116.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the authors, the SWAN would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following: Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor—Siobán Harlow, PI 2011–present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA—Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999–present; Robert Neer, PI 1994–1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL—Howard Kravitz, PI 2009–present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994–2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser—Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles—Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY—Carol Derby, PI 2011–present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010–2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004–2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry—New Jersey Medical School, Newark—Gerson Weiss, PI 1994–2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA—Karen Matthews, PI. NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD—Chhanda Dutta 2016–present; Winifred Rossi 2012–2016; Sherry Sherman 1994–2012; Marcia Ory 1994–2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD—Program Officers. Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor—Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services). Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA—Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012–present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001–2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA—Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995–2001. Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair and Chris Gallagher, Former Chair. We also thank the study staff and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Funding

This research was part of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), which has grant support from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, through the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Nursing Research, and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (Grants Nos: U01NR004061, U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). Supplemental funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH59689) is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors participated in the design, execution, and analysis of the paper, and they have approved the final version. HHSL developed research hypotheses, performed statistical analyses, and wrote the entire manuscript. JTB reviewed and edited the entire manuscript to improve the focus and clarity. AIN provided knowledge and guidance for statistical analyses, particularly mediation analyses, and programming support. MMB provided input on statistical analyses and interpretation of findings. GAR reviewed and made suggestions for the entire manuscript and provided psychiatric expertise. JGB reviewed and helped in addressing the implications of study findings in community settings.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclaimer

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, Office of Research on Women’s Health, or National Institutes of Health.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, HH.S., Naimi, A.I., Brooks, M.M. et al. Child maltreatment as a social determinant of midlife health-related quality of life in women: do psychosocial factors explain this association?. Qual Life Res 27, 3243–3254 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1937-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1937-x