Abstract

Purpose

To describe quality of life (QoL) outcome measures that are reported in the literature in patients waiting for outpatient orthopaedic/musculoskeletal specialist care and how waiting impacts on QoL in these terms.

Methods

A subset of studies reporting on QoL outcome measures were extracted from literature identified in a recent scoping search of Medline, Embase, Pubmed, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (Prospero registration CRD42016047332). The systematic scoping search examined impacts on patients waiting for orthopaedic specialist care. Two independent reviewers ranked study design using the National Health and Medical Research Council aetiology evidence hierarchy, and appraised study quality using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tools. QoL measures were mapped against waiting period timepoints.

Results

The scoping search yielded 142 articles, of which 18 reported on impact on QoL. These studies reported only on patients waiting for hip and/or knee replacement surgery. The most recent study reported on data collected in 2006/7. The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index and the SF-36 were the most commonly reported QoL measures. QoL was measured at variable timepoints in the waiting period (from a few weeks to greater than 12 months). The impact of waiting on QoL was inconsistent.

Conclusion

The evidence base was over 10 years old, reported only on patients with hip and knee problems, and on limited QoL outcome measures, and with inconsistent findings. A better understanding of the impact on QoL for patients waiting for specialist care could be gained by using standard timepoints in the waiting period, patients with other orthopaedic conditions, comprehensive QoL measures, as well as expectations, choices and perspectives of patients waiting for specialist care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders are those which affect the joints, muscles, bones and soft tissue. They can affect people of any age; however, in many cases they can become recurrent and lifelong conditions that people are required to manage on a daily basis [1, 2]. Musculoskeletal conditions are becoming more prevalent, demanding more of the global health system and resulting in significant pain and suffering for large numbers of the population [1, 3]. Vos et al. estimated that globally musculoskeletal disorders contributed 18.5% of years lived with a disability in 2015, a 68% increase from 1990 [3]. Hip and knee osteoarthritis alone are reported to be the 11th highest contributor to global disability [4]. The health-related quality of life of patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis compared with that of population controls is consistently worse, including ability to move, sexual activity, vitality, discomfort, depression and distress [5]. What is unclear is how this changes over time.

The traditional pathway for many patients with an orthopaedic complaint is a referral by their general practitioner (GP) or by other outpatient departments to an orthopaedic specialist for assessment and management in either the public or the private sector depending on the insured status of the patient [6, 7]. Due to the rising number of people with musculoskeletal disorders there has been an increased demand for such services, resulting in patients in the public sector having to wait for consultation and subsequent treatment [6, 8]. In many cases, patients wait for treatment with little or no input from other health service providers and patients have reported that they feel disconnected from the health service providers, leading to frustration and anxiety [9,10,11,12]. Patients can wait for months for their initial appointment with an orthopaedic specialist and then often are subject to a further wait for any treatment, sometimes waiting for over a year [13, 14] and up to 3 years in some cases [6].

Placement on a waiting list has for many years provided a means of balancing demand for services with capacity to provide care [15]. There is intense interest from policy makers in waiting lists and they are commonly used as markers of success (or not) in the delivery of health services [16]. Patients are often disgruntled by lengthy waiting periods and this can lead to dissatisfaction with healthcare providers, with patients often reporting that waiting impacts on their life [17].

Whilst it is reasonable to imagine that waiting for long periods of time for management and treatment is likely to have a negative impact on a patient’s quality of life, this is poorly understood. There is potential for altered capacity to perform usual activities of daily life, loss of social integration and altered productivity levels, at home and/or in society [18, 19]. The impact of waiting on the success of any subsequent treatment is also poorly understood; however, there is some low-level evidence to suggest that prolonged waiting for care impacts on the outcome and satisfaction with subsequent surgical treatment [19, 20].

This review aimed to systematically investigate what quality of life outcome measures are reported in the literature in patients waiting for orthopaedic/musculoskeletal consultation and/or treatment and how waiting impacts on quality of life.

Methods

Study design

This systematic scoping review builds on our recently published scoping review which reported on the volume, hierarchy and quality of the available peer-reviewed literature on the impact of waiting for an orthopaedic consultation, exploring this issue in broad terms [21].

Framework for literature exploration

The literature was mapped into a ubiquitous journey that described the stages of waiting for orthopaedic consultations. This approach provided a framework for considering when in the waiting journey outcomes were measured, and why. The patient journey is reproduced from the scoping review [21]—see Fig. 1.

Review registration

The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016047332).

Reporting standard

This review was reported in line with the PRISMA statement [22].

Review purpose

The purpose of this systematic scoping review was to undertake a focussed analysis of the quality of life outcome measures and their utility and results reported in the peer-reviewed literature when used to assess the impact of waiting for consultation/treatment for patients with an orthopaedic/musculoskeletal complaint.

Search strategy

The search was conducted in March 2016 and updated in Aug 2017.

Search terms

A PO (participants, outcomes) search strategy was applied.

-

Population: Adult patients (18 years and over) with an orthopaedic and/or musculoskeletal complaint for which they had been referred to an outpatient clinic for specialist consultation/treatment. No limitations were applied in terms of diagnostic categories.

-

Outcomes: Impact of waiting was explored in terms of the impact on the patient’s quality of life, function and social integration using a recognised quality of life outcome measure.

MeSH headings or Boolean operators were used with the search terms, relevant to the database being searched. The search terms are outlined in Table 1.

Search engines

Library databases of Medline, Embase, Pubmed and NHS Economic evaluation database (NHS-EED) were searched, from each database inception date. Broad search terms and inclusion criteria were applied in an attempt to identify all relevant papers related to patients with an orthopaedic/musculoskeletal complaint waiting for specialist consultation/treatment.

Additional searching

The reference lists of the papers identified through the database searches were hand searched to identify additional papers which were relevant, but which had not been identified from the literature search.

Study identification

The titles and abstracts of each potentially relevant paper were screened by two researchers (JM, AT) independently using Covidence© for relevance to the study purpose. In the case of dispute, a third author (KG) arbitrated.

Eligibility criteria

To ensure maximum information was obtained, studies of any design were included. Thus all papers that described waiting for an orthopaedic/specialist appointment or treatment for a musculoskeletal condition in an adult population and met the inclusion criteria were considered to be relevant.

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not report on the impact of waiting for management of an orthopaedic/musculoskeletal complaint by a medical specialist, if they described children (younger than 18 years), if they did not report on quality of life impacts using a recognised measure to allow for comparison of findings, were not available in full text or were not in English.

Hierarchy of evidence

Hierarchy of evidence was reported using NHMRC criteria relevant to the study question [23]. Due to the nature of investigations into the impact of waiting it is only possible to determine a causal relationship using observational studies, therefore it is most appropriate to utilise the NHMRC ‘Aetiology’ hierarchy when determining the hierarchy of evidence for the relevant studies.

Critical appraisal

This was undertaken by two independent reviewers (AT, JM) using the relevant appraisal tool. Any level II studies were critically appraised with Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) and Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist [24], and any Level III or IV studies were critically appraised with were compared, and disagreements discussed and resolved using an independent arbiter (KG).

Data extraction

Data were extracted by two reviewers working together (JM, AT). Data were extracted into a custom-built MS Excel sheet to allow for ready comparison between the outcomes from the extracted studies. Extracted data included country of research, patient demographics, health condition, study design, waiting list description, length of wait (where described), where in the patient journey the research was conducted, the measures of quality of life that had been reported and the number of patients in each study.

Results

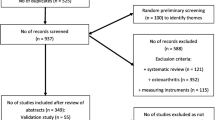

The search identified 2434 potentially eligible studies (see Fig. 2). There were 393 duplicates, and another 792 articles were removed, after considering title and abstract, as not meeting the inclusion criteria. This left 142 articles that were considered for inclusion.

Handsearching

Included in these potentially relevant articles was a systematic review which summarised 15 primary articles [25]. After debate, it was decided that, as aims of our review differed from the review aims, we should consider the 15 individual papers in the Hoogeboom et al. (2009) review, rather than the review itself. A further six references were identified from handsearching the remaining included papers’ reference lists.

Search results

Ten of the 15 papers identified in the review [25] were relevant to this study. The remaining five papers in this review had already been identified during the search, and had been excluded. Eight other papers were identified from our systematic review process, resulting in 18 papers finally included in this review. See Fig. 2 (CONSORT diagram). The total number of patients reported in the papers included in this review was 2486. The results from two studies [26, 27] were excluded from the data analysis as they did not include raw data in their papers, as such no independent assessment and collation of the findings could be undertaken, therefore the patient’s from this study have not been added to the total number.

Hierarchy and quality of evidence

The included papers reflected two level II papers [28, 29] and the remaining mostly III-3 cohort studies [13, 14, 19, 26, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] (see Table 2). Table 2 also reports critical appraisal scores; the studies ranged from moderate to good quality, therefore the results from this review represent a relatively trustworthy body of evidence. Interestingly, the area of poorest quality in over half of the papers was in reporting of results and how the information was represented; confidence intervals were not reported in over half of the studies. The nature of the research questions in these studies predominantly pertains to a change in status over time, therefore a cohort study is an appropriate methodology to explore this.

Musculoskeletal presentations and assessments

All included papers explored the impact of waiting for a total hip replacement (THR), total knee replacement (TKR) or both TKR and THR. No identified studies explored the impact of waiting for any other musculoskeletal disorders or treatments. Only two papers [29, 38] described a standardised grading system for severity of joint disease, one using the using the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) atlas and the other Kellgren–Lawrence (K/L) grading system (see Table 3). The remaining papers reported only that the patients had sufficiently severe arthritis to warrant a joint replacement.

Data collection time points

There was variability in the time points in the patient journey, when patients were assessed/re-assessed using the standardised measures, particularly in the pre-operative period. All studies collected data at the time the patient was placed on the surgical waitlist, with only one exception [27], only 1 paper explored the time period prior to being on the surgical waitlist [39]. All papers collected data at admission for surgery (or pre-admission clinic—usually within 2 weeks of admission), whilst only 3 papers collected data between being placed on the waiting list and attending pre-admission clinic or admission to hospital [29, 37, 39]. There was a more standardised approach reported in the post-operative period—see Fig. 3.

AKSS American Knee Society Score, SF-36 Short-Form 36, WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index®, 15D 15-dimensional health-related quality of life measure, Kessler K10 Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, AQoL 12 assessment of quality of life 12, EQ-5D EuroQoL 5-dimensions, NHP Nottingham health profile

The waiting period

In all but one of the studies, the waiting period was defined at the time the patient was placed on the surgical waiting list (see Fig. 1). Only one paper described the waiting period from the time the GP referred the patient to the speciality service [39]. This paper describes a waiting period of 1.8–14.2 months (mean 9.8 months) from point of referral by their GP to attending an orthopaedic specialist appointment for a knee complaint. All patients who were deemed to not require a TKR due to osteoarthritis was removed from the study at the point of their orthopaedic appointment. During the waiting period for Orthopaedic assessment there was a statistical deterioration in function and pain on the American Knee Score (AKS), but not on the Oxford Knee Score (OKS). The waiting time between an orthopaedic appointment and surgery ranged from 9.1 to 22 months (mean 13.3 months), however what the authors do not clearly state is the whole waiting time (from GP appointment to surgery), but the patients in this study had a statistically significant deterioration in function on the AKS, but not pain and a statistically significant deterioration in their OKS scores. The remaining studies vary in the time points in the patient’s journey that they assess. Eight studies [13, 29, 30, 33, 35,36,37, 39] monitored patients from point of being placed on the waiting list to point of surgery. Seven papers [14, 19, 28, 31, 32, 34, 26] monitored patients from point of being placed on the surgical waiting list, to point of surgery and varying periods post-operatively.

Collation of results

The results from all studies have been synthesised (see Table 4), reported in Table 4 is the length of wait reported in each study, the QoL outcome measure used, the number of participants in the study, the length of follow-up and a synthesis of the findings. Further dissection of the study results, by waiting time is outlined in Table 5, reporting results by waiting period for treatment; 0–3 months wait, 3–6 months wait, 6–9 months wait, 9–12 months wait and in excess of 12 months. Overall there are inconsistencies in the study findings, with limited linkage identified between length of wait and whether patients deteriorate, stay the same or improve in their quality of life. However, the bulk of the findings appears to suggest either a deterioration in QoL or a stasis. Only four studies reported an improvement in QoL and/or pain and function at varying stages of waiting, with the exception of a 0–3 month wait where no improvements were reported for this cohort of patients [31, 34, 36, 39]. Due to the heterogeneity of the identified studies, a meta-analysis of the study results was not possible.

Outcome measures used

In 11 of the 18 included studies, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index® (WOMAC) was used as a means of assessing pain, stiffness and physical function. In 9 of the 18 studies, the SF-36 was used to measure QoL impacts making them the two most commonly used tools in this review (see Table 4). Of the other outcome measures used, the EQ-5D was used in three separate studies, only two others were used more than once, WOMAC of the contralateral knee was used in two separate studies and 15D were also used in two separate studies.

The most common points of assessment of QoL in the patient journey were at the outpatient appointment, where the patient met the surgeon and the decision was made to place them on the surgical waiting list and at point of surgery. The use of the outcome measures reported in the studies and the study results are mapped against the patient journey in Table 5.

Discussion

This is the first systematic scoping review to our knowledge that explores waiting for orthopaedic assessment and/or treatment on quality of life, the measures used to assess this and the outcomes reported. The studies available in this area were limited to those patients waiting for a total hip or knee replacement due to a diagnosis of osteoarthritis predominantly. No other studies were identified that explore the impact of waiting for other musculoskeletal conditions.

Assigning patients to the surgical waiting list

Only two studies [29, 38] identified that a standard measure was used to identify patients (K/L and OASRI), the remaining studies reported patients were identified based on clinical assessment in isolation. This is an area that has attracted recent research; due to the costs associated with arthroplasty surgery, there is significant interest in surgery outcomes and whether the treatment is being offered to appropriate patients [41,42,43]. It is proposed that approximately 25% of patients who have a joint arthroplasty were inappropriately provided that treatment, which has led to interest into the clinical decisions that lead to a patient being offered arthroplasty surgery [42,43,44,45].

The interest in arthroplasty outcomes has led to further research into the validity and reliability of these two grading scales (K/L and OARSI) reported in this systematic review [46]. Significant discrepancies have been noted [46], with radiographic OA being twice as commonly reported using the OARSI atlas compared with the K/L system. However, Kohn et al. 2016 also raised concerns regarding the inter-rater reliability of the K/L system with considerable variability between observers noted [47]. Other issues include the sensitivity to change of these scales and most importantly the link between radiographic findings and function and pain levels, where there is controversy in the literature regarding the link between severity of radiographic changes and symptoms [47,48,49,51]. These factors have important implications when assessing the impact of waiting for orthopaedic surgery/care; the appropriateness of the patients being placed on the list will influence the impact of the waiting period. The appropriateness of referrals to specialists is a longstanding problem in healthcare; many patients are placed on waiting lists for extended periods of time only to establish that they have been incorrectly referred [8, 52], a factor that will influence the impact of waiting. However, it is beyond the scope of this review to explore this concern further.

The waiting period

In all but one of the included studies, the waiting period was deemed to start once the patient had been placed on a surgical waitlist (see Fig. 1—outlining the waiting list journey), with only one paper discussing the period of waiting for a specialist appointment [39]. In this study, it was of note that from orthopaedic assessment to surgery the least changes occurred, a statistically significant change in the total AKS, but not the elements of pain and stiffness individually and not the OKS, this may suggest that once a plan is in place, or they have been provided with a definitive diagnosis, there is a change in the severity and speed of the patient’s deterioration.

Whilst in the context of tertiary hospitals there is significant interest in the surgical waiting lists internationally, a more holistic approach to research in this field should include the whole patient journey as described in Fig. 1. As with the one study that explored that aspect of waiting, there was a slowing in the deterioration once an appointment had been attended at this hospital that perhaps provided additional information, investigations and/or treatment options. Therefore, initiatives that can intervene during this period of the patients waiting journey maybe of significant value to the organisation and more importantly the patient. Such initiatives have been introduced sporadically in countries including the UK, Australia and Sweden, in the form of orthopaedic triage often by professionals other than Doctors. As yet little is known about the merits of these initiatives in quality of life terms and what impact they have on patients waiting for specialist care. Some studies have explored interventions whilst waiting [53, 54], again these are predominantly limited to those patients waiting for joint replacement surgery. Whilst there is a lack of clarity regarding the impact of waiting, it may be difficult to accurately interpret these results as with no intervention it is unclear why some people improve, some stay the same and some deteriorate.

However, perhaps of more urgent need is exploring the journey of patients where surgery is not an option, whether this is due to alternative diagnoses (i.e. non-operable conditions), co-morbidities or patient preference, as this is an unknown entity at this time.

Outcome measures

The WOMAC is disease specific, and is one of the most commonly used outcome measures in arthritis research, particularly for osteoarthritis of the hip and knee [55]. The WOMAC is a self-reported instrument with five items for scoring pain, two for stiffness and 17 for functional limitation. Functional tasks include stair use, standing up from sitting, getting in and out of the car, shopping, putting on and taking off socks, bending and walking, tasks which have relevance to lower limb pathology. WOMAC has been widely translated and validated in other languages. The WOMAC instrument has been shown to be less sensitive to detecting change over time in some intervention-based studies [55,56,57,59]. It is proposed that the rigid nature of the questions may impact on sensitivity to change, particularly when compared with more open-ended measures [56]. When compared with self-reported pain on a nominated activity, the WOMAC index has been shown to be less sensitive to change in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee [56]. This raises questions around the appropriateness of using the WOMAC index to track patients over time, as sensitivity to change is crucial to tracking deterioration in patients waiting for care.

The SF36 is a broad quality of life measure, estimating health status in domains of vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social function and mental health [60], all essential factors for patients with a musculoskeletal complaint. It has been widely used in research internationally, on many different health conditions to evaluate individual patient’s health status and compare this to population norms, research the cost-effectiveness of treatments and monitor and compare disease burdens. A number of studies have explored the sensitivity of the SF-36 to change, Kean et al. observed that it may not be sufficiently sensitive to change when compared with other measures such as PROMIS Pain Interference short forms and the Brief Pain Inventory [61]. Similar findings were reported by McElhone et al. in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) which has similar symptoms to many musculoskeletal disorders [62]. These findings raise questions regarding the appropriateness of the SF-36 for use in research into the impact of waiting.

Limitations/issues

A significant issue in the results was that the most recent data collection period using a recognised quality of life outcome measure was 2006–7, reflecting that this area of research has not been explored for 10 years, despite the continually rising demand for orthopaedic care.

Conclusions

The focus of this review was to establish the impact of waiting for orthopaedic care and what established outcome measures are used to calculate this. The impact of waiting is a complex and multi-dimensional issue that is difficult to quantify. There are a number of qualitative studies that aim to establish the experiences of patients waiting for care [8,9,10,11, 17, 62, 63], as waiting is commonplace in modern day healthcare. These studies suggest increased social isolation, psychological distress and deterioration in self-reported health and mobility. However, this systematic review has established that as yet there is no repeatable validated outcome measure that captures these factors, it allows them to be monitored and inform strategies to address them.

This systematic scoping review also highlights that there is a lack of clarity regarding the impact of waiting for a total hip or knee replacement on patient’s quality of life and what outcome measures can be best used to assess this impact. There is no information available for other musculoskeletal complaints. Some studies note an improvement in quality of life, whilst others report no change or a deterioration. These discrepancies may be due to the choice of outcome measure and their ability to detect change or relate to the choice of patient selected for a joint replacement and therefore placement on an orthopaedic outpatient waiting list.

What is clear is that there is an urgent need for further work to investigate the impact of waiting for orthopaedic care on patient’s quality of life and what measures can be used to assess this, particularly for musculoskeletal conditions other than those awaiting hip or knee joint replacement. Waiting is an accepted part of modern day public health care, yet at this time little is understood about the short- and long-term impact of waiting on patients and the impact it may have on subsequent treatment.

References

Kiadaliri, A. A., Woolf, A. D., & Englund, M. (2017). Musculoskeletal disorders as underlying cause of death in 58 countries, 1986–2011: Trend analysis of WHO mortality database. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1428-1.

Woolf, A. D., Vos, T., & March, L. (2010). How to measure the impact of musculoskeletal conditions. Best Practice & Clinical Rheumatology, 24, 723–732.

Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Naghavi, M., Lozano, R., Michaud, C., Ezzati, M., et al. (2010). Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 380, 2163–2196.

Cross, M., Smith, E., Hoy, D., Nolte, S., Ackerman, I., March, L., et al. (2014). The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 73(7), 1323–1330.

Hirvonen, J., Blom, M., Tuominen, U., Seitsalo, S., Lehto, M., Paavolainen, P., Hietaniemi, K., Rissanen, P., & Sintonen, H. (2006). Health-related quality of life in patients waiting for major joint replacement. A comparison between patients and population controls. Health and Related Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-3.

Walters, J. L., Mackintosh, S., & Sheppard, L. (2012). The journey to total hip or knee replacement. Australian Health Review, 36, 130–135.

Mandzuk, L. L., McMillan, D. E., & Bohm, E. R. (2010). The bone and joint decade in Canada: A look back and a look forward. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 14, 12–17.

Morris, J., Grimmer-Somers, K., Kumar, S., Murphy, K., Gilmore, L., Ashman, B., Perera, P., Vine, K., & Coulter, C. (2011). Effectiveness of a physiotherapy-initiated telephone triage of orthopedic waitlist patients. Patient Related Outcome Measures, 2, 151–159.

Jacobson, A. F., Myerscough, R. P., Delambo, K., Fleming, E., Huddleston, A. M., Bright, N., & Varley, J. D. (2008). Patient’s perspectives on total knee replacement. American Journal of Nursing, 108(5), 54–63.

Hall, M., Migay, A. M., Persad, T., Smith, J., Yoshida, K., Kennedy, D., & Pagura, S. (2008). Individuals’ experience of living with osteoarthritis of the knee and perceptions of total knee arthroplasty. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 24(3), 167–181.

Parsons, G. E., Godfrey, H., & Jester, R. F. (2009). Living with severe osteoarthritis while awaiting hip and knee joint replacement surgery. Musculoskeletal Care, 7(2), 121–135.

Mats-Sjöling, R. N., Ågren, Y., Olofsson, N., Hellzén, O., & Asplund, K. (2005). Waiting for surgery; living a life on hold—A continuous struggle against a faceless system. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42(5), 539–547.

Desmeules, F., Dionne, C. E., Belzile, E., Bourbonnais, R., & Frémont, P. (2010). The burden of wait for knee replacement surgery: Effects on pain, function and health-related quality of life at the time of surgery. Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep469.

Fielden, J. M., Cumming, J. M., Fracs Horne, J. G., Fracs Devane, P. A., Slack, A., & Gallagher, L. M. (2005). Waiting for hip arthroplasty economic costs and health outcomes. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 20(8), 990–997.

Curtis, A. J., Russel, C. O. H., Stoelwinder, J. U., & McNeil, J. J. (2010). Waiting lists and elective surgery: Ordering the queue. Medical Journal of Australia, 192(4), 217–220.

Dixon, H., & Siciliani, L. (2009). Waiting-time targets in the healthcare sector: How long are we waiting. Journal of Health Economics, 28, 1081–1098.

Sanmartin, C., Berthelot, J.-M., & McIntosh, C. N. (2007). Determinants of unacceptable waiting time for specialized services in Canada. Healthcare Policy, 2(3), 141–154.

Robling, M. R., Pill, R. M., Hood, K., & Butler, C. C. (2009). Time to talk? Patient experiences of waiting for clinical management of knee injuries. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 18(2), 141–146.

Desmeules, F., Dionne, C. E., Belzile, E., Bourbonnais, R., & Frémont, P. (2010). The impacts of pre-surgery wait for total knee replacement on pain, function and health-related quality of life six months after surgery. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 1–10.

Lizaur-Utrilla, A., Martinez-Mendez, D., Mirallles-Muñoz, F. A., Mareo-Gomez, L., & Lopez-Prats, F. A. (2016). Negative impact of waiting time for primary total knee arthroplasty on satisfaction and patient-reported outcome. International Orthopaedics, 40, 2303–2307.

Morris, J., Twizeyemariya, A., & Grimmer, K. (2017). The cost of waiting on an orthopaedic waiting list: A scoping review. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 12(2), 42–54.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Merlin, T., Weston, A., & Tooher, R. (2009). Extending an evidence hierarchy to include topics other than treatment: Revising the Australian ‘levels of evidence’. BMC Medical Research Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-34.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2014). CASP checklists http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_40b9ff0bf53840478331915a8ed8b2fb.pdf. Oxford: CASP.

Hoogeboom, T. J., van den Ende, C. H. M., van der Slius, G., Elings, J., Dronkers, J. J., Aiken, A. B., & van Meeteren, N. L. U. (2009). The impact of waiting for total joint replacement on pain and functional status: A systematic review. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 17, 1420–1427.

Bachrach-Lindstöm, M., Karlsson, S., Pettersson, L., & Johansson, T. (2008). Patients on the waiting list for total hip replacement: A 1-year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22, 536–542.

Brownlow, H. C., Benjamin, S., Andrew, J. G., & Kay, P. (2001). Disability and mental health of patients waiting for total hip replacement. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 83, 128–133.

Hirvonen, J., Tuominen, U., Seitsalo, S., Lehto, M., Paavolainen, P., Hietaniemi, K., Rissanen, P., Sintonen, H., & Blom, M. (2009). The effect of waiting time on Health-related quality of life, pain and physical function in patients awaiting primary total hip replacement: A randomized controlled trial. Value in Health, 12(6), 942–947.

Nunez, M., Nunez, E., Segur, J. M., Macule, F., Quinto, L., Hernandez, M. V., & Vilalta, C. (2006). The effect of an educational program to improve health-related quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis on waiting list for total knee replacement: A randomized study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 14, 279–285.

Ackerman, I. N., Bennell, K. L., & Osborne, R. H. (2011). Decline in health-related quality of life reported by more than half of those waiting for joint replacement surgery: A prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 108(12), 1–9.

Ostendorf, M., Buskens, E., van Stel, H., Schrijvers, A., Marting, L., Dhert, W., & Verbout, A. (2004). Waiting for total hip arthroplasty: Avoidable loss in quality time and preventable deterioration. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 19(3), 302–309.

March, L., Cross, M., Tribe, K., Lapsley, H., Courtenay, B., & Brooks, P. (2002). Cost of joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis: The patients’ perspective. The Journal of Rheumatology, 29(5), 1006–1014.

Ahmad, I., & Konduru, S. (2007). Change in functional status of patient whilst awaiting primary total knee arthroplasty. Surgeon, 5(5), 266–267.

Chakravarty, D., Tang, T., Vowler, S. L., & Villar, R. (2005). Waiting for primary hip replacement—A matter of priority. Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 87, 269–273.

Kapstad, H., Rustøen, T., Hanestad, B. R., Moum, T., Langeland, N., & Stavem, K. (2007). Changes in pain, stiffness and physical function in patients with osteoarthritis waiting for hip or knee joint replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 15, 837–843.

Kelly, K. D., Voaklander, D. C., Johnston, D. W. C., Newman, S. C., & Suarez-Almazor, M. E. (2001). Change in pain and function while waiting for major joint arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 16(3), 351–359.

McHugh, G. A., Luker, K. A., Campbell, M., Kay, P. R., & Silman, A. J. (2006). Pain, physical functioning and quality of life of individuals awaiting total joint replacement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14, 19–26.

Nilsdotter, A. K., & Lohmander, L. S. (2002). Age and waiting time as predictors of outcome after total hip replacement for osteoarthritis. Rheumatology, 41, 1261–1267.

Pace, A., Orpen, N., Doll, H., & Crawford, E. J. (2005). The natural history of severe osteoarthritis of the knee in patients awaiting total knee arthroplasty. The European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology, 15, 309–312.

Tuominen, U., Sintonen, H., Hirvonen, J., Seitsalo, S., Paavolainen, P., Lehto, M., Hietaniemi, K., & Blom, M. (2010). Is longer waiting time for total knee replacement associated with health outcomes and medication costs? Randomized clinical trial. Value in Health, 13(8), 998–1004.

Cobos, R., Latorre, A., Aizpuru, F., Guenaga, J. I., Sarasqueta, C., Escobar, A., Garcia, L., & Herrera-Espiñeira, C. (2010). Variability of indication criteria in knee and hip replacement: An observational study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 11, 249.

Dowsey, M. M., Gunn, J., & Choong, P. F. M. (2014). Selecting those t refer for joint replacement: Who will likely benefit and who will not? Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 28, 157–171.

Quintana, J. M., Bilbao, A., Escobar, A., Azkarate, J., & Goenaga, J. I. (2009). Decision trees for indication of total hip replacement on patients with osteoarthritis. Rheumatology, 48, 1402–1409.

Dieppe, P., Lim, K., & Lohmander, S. (2011). Who should have knee joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis? International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 14, 175–180.

Judge, A., Cooper, C., Williams, S., Dreinhoefer, K., & Dieppe, P. (2010). Patient-reported outcomes one year after primary hip replacement in a European collaborative cohort. Arthritis Care & Research, 62(4), 480–488.

Culvenor, A. G., Engen, C. N., Øiestad, B. E., Engebretsen, L., & Risberg, M. A. (2015). Defining the presence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: A comparison between the Kellgren and Lawrence system and OARSI atlas criteria. Knee Surgery, Arthroscopy and Sports Traumatology, 23, 3532–3539.

Kohn, M. D., Sassoon, A. A., & Fernando, N. D. (2016). Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 474, 1886–1893.

Cubukcu, D., Sarsan, A., & Alkan, H. (2012). Clinical study relationships between pain, function and radiographic findings in osteoarthritis of the knee: A cross-sectional study. Arthritis. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/984060.

Creamer, P., Lethbridge-Cejku, M., & Hochberg, M. C. (2000). Factors associated with functional impairment in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology, 39(5), 490–496.

Herman, A., Chechik, O., Segal, G., Kosashvili, Y., Lador, R., Salai, M., Mor, A., Elbaz, A., & Haim, A. (2015). The correlation between radiographic knee OA and clinical symptoms—Do we know everything? Clinical Rheumatology, 34, 1955–1960.

Komatsu, D., Hasegawa, Y., Kojima, T., Seki, T., Higuchi, Y., & Ishiguro, N. (2016). Absence of a relationship between joint space narrowing and osteophyte formation in early knee osteoarthritis among Japanese community dwelling elderly individuals: A cross-sectional study. Modern Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2016.1232775.

Burn, D., & Beeson, E. (2014). Orthopaedic triage: Cost effectiveness, diagnostic/surgical and management rates. Clinical Governance: An International Journal, 19(2), 126–136.

Parson, G., Jester, R., & Godfrey, H. (2013). A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a health maintenance clinic intervention for patients undergoing elective primary total hip and knee replacement surgery. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 17, 171–179.

Wallis, J. A., & Taylor, N. F. (2011). Pre-operative interventions (non-surgical and non-pharmacological) for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis awaiting joint replacement surgery—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 19, 1381–1395.

Roos, E. M., Klassbo, M., & Lohmander, L. S. (1999). WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, 28(4), 210–215.

Parkes, M. J., Callaghan, M. J., O’Neill, T. W., Forsythe, L. M., Lunt, M., & Felson, D. T. (2016). Sensitivity to change of patient-preference measures for pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Data from two trials. Arthritis Care & Research, 68(9), 1224–1231.

Zampelis, V., Ornstein, E., Franzen, H., & Atroshi, I. (2014). A simple visual analog scale for pain is as responsive as the WOMAC, the SF-36, and the EQ-5D in measuring outcomes of revision hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica, 85, 128–132.

Lineker, S. C., Badley, E. M., Hawker, G., & Wilkins, A. (2000). Determining sensitivity to change in outcome measures used to evaluate hydrotherapy exercise programs for people with rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care & Research, 13, 62–65.

Bellamy, N., Campbell, J., & Syrotuik, J. (1999). Comparative study of self-rating pain scales in osteoarthritis patients. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 15, 113–119.

Ware, J. E. Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36 item short form health survey (SF 36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30, 473–483.

Kean, J., Monahan, P. O., Kroenke, K., Wu, J., Yu, Z., Stump, T. E., & Krebs, E. E. (2016). Comparative responsiveness of the PROMIS pain interference short forms, brief pain inventory, PEG, and SF-36 bodily pain subscale. Medical Care, 54(4), 414–421.

McElhone, K., Abbott, J., Sutton, C., Mullen, M., Lanyon, P., Rahman, A., Yee, C., Akil, M., Bruce, I. N., Ahmad, Y., & Gordon, C. (2016). The L. sensitivity to change and minimal important differences of the LupusQoL in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care & Research, 68(10), 1505–1513.

Conner-Spady, B. L., Marshall, D. A., Hawker, G. A., Bohm, E., Dunbar, M. J., Frank, C., & Noseworthy, T. W. (2015). You’ll know when you’re ready: A qualitative study exploring how patients decide when the time is right for joint replacement surgery. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), pp. 1–10.

Acknowledgements

Data management and formatting support was available from Ashley Fulton, Heath Pillen and Holly Bowen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT and JM for literature searching, critical appraisal; AT, JM, KG for debating and organising the findings; drafting and reading subsequent drafts and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morris, J., Twizeyemariya, A. & Grimmer, K. What is the current evidence of the impact on quality of life whilst waiting for management/treatment of orthopaedic/musculoskeletal complaints? A systematic scoping review. Qual Life Res 27, 2227–2242 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1846-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1846-z