Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the factor structure of the revised Partners in Health (PIH) scale for measuring chronic condition self-management in a representative sample from the Australian community.

Methods

A series of consultations between clinical groups underpinned the revision of the PIH. The factors in the revised instrument were proposed to be: knowledge of illness and treatment, patient–health professional partnership, recognition and management of symptoms and coping with chronic illness. Participants (N = 904) reporting having a chronic illness completed the revised 12-item scale. Two a priori models, the 4-factor and bi-factor models were then evaluated using Bayesian confirmatory factor analysis (BCFA). Final model selection was established on model complexity, posterior predictive p values and deviance information criterion.

Results

Both 4-factor and bi-factor BCFA models with small informative priors for cross-loadings provided an acceptable fit with the data. The 4-factor model was shown to provide a better and more parsimonious fit with the observed data in terms of substantive theory. McDonald’s omega coefficients indicated that the reliability of subscale raw scores was mostly in the acceptable range.

Conclusion

The findings showed that the PIH scale is a relevant and structurally valid instrument for measuring chronic condition self-management in an Australian community. The PIH scale may help health professionals to introduce the concept of self-management to their patients and provide assessment of areas of self-management. A limitation is the narrow range of validated PIH measurement properties to date. Further research is needed to evaluate other important properties such as test–retest reliability, responsiveness over time and content validity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The burden of chronic conditions (e.g. diabetes, heart disease and depression) is unquestionably a leading challenge to global health. It impacts at personal and community levels and is strongly linked to the high utilisation of health services and medical spending [1, 2]. In Australia, approximately one-third of the population has at least one chronic condition [3, 4]. To help address this, a trial (Council of Australian Governments (COAG) National Co-ordinated Care Trials) was conducted to improve the health outcomes and treatment options for patients with chronic and complex health conditions. A mid-trial review found that health benefits from coordinated care depended more on patients’ self-management behaviour than severity of illness, a factor leading to the development of the Flinders Program of Self- Management Support [5–7]. In general, self-management programmes aim to help individuals better manage their medical treatment and cope with the impact of the condition on their physical and mental well-being [8].

To enable the meaningful measurement of the Flinders Program, the Partners in Health (PIH) scale was developed as a generic instrument for use in conjunction with patient assessment and goal setting processes [9]. The original version of PIH was intended to be a short and precise tool comprising of 11 self-rated items to reflect the definition of chronic condition self-management [9]. This definition incorporated a “holistic” approach to self-management with the aim to empower the individual through proactive strategies in managing the physical and psychosocial components of their condition. The five underpinning principles to the derivation of PIH items endorsed the importance of the partnership between the patient and their carer(s) and health professionals. Pilot findings from the evaluation of PIH measurement properties indicated satisfactory internal consistency, inter-rater reliability and an underlying 3-factor solution from exploratory factor analysis. Both patients with chronic conditions and health professionals rated the scale as acceptable and easy to use (face validity) and health professionals endorsed its clinical utility [9].

Subsequent feedback from the Flinders Program clinicians then resulted in the addition of two new items, and two items relating to arranging and attending appointments were collapsed into one [10]. This led to the expansion of the five principles of chronic condition of self-management to six;

-

1.

Know their condition and various treatment options.

-

2.

Negotiate a plan of care.

-

3.

Engage in activities that protect and promote health.

-

4.

Monitor and manage the symptoms and signs of the condition(s).

-

5.

Manage the impact of the condition on physical functioning, emotions and interpersonal relationships.

-

6.

Adopt lifestyles that promote health.

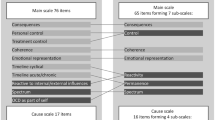

The internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity of the 12-item PIH version were then confirmed in an Australian study by Petkov and colleagues and shown to be comprised of four factors: knowledge of illness, coping with illness, symptom management and adherence to treatment [10].

In recent years, changing social and demographic structures have led to major shifts in the nature of patient and health professional relationships [11, 12]. The WHO definition of health has been redefined as “the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social, physical and emotional challenges” [13] (cited in [14]). A key element to defining chronic condition self-management education is that the person can apply these skills to three aspects of their health condition: medical, social (interpersonal factors) and emotional (intrapersonal factors) [11]. The patient empowerment philosophy has subsequently become even more fundamental to models of chronic condition self-management where the beliefs and values of the person are recognised and respected [12, 15–20]. The role of empowering patients to care for themselves in the way they prefer is considered to be central to partnerships between providers and patients, for example, in patients living with cancer as a chronic illness [21]. Empowerment shifts the balance in power relations between providers and patients where the patient has more control over their health care [12]. Indicators of patient empowerment include self-efficacy and proactivity in making autonomous and informed decisions about health and health care that fit their cultural and psychosocial needs [20, 22–24]. Furthermore, such indicators are reflective of the levels of collaborative relationships between patient and health care providers [24].

Individuals with chronic illness are also typically required to self-manage accompanying emotions such as anger and frustration in order to uphold a reasonable quality of life [25–28]. Links between coping with chronic illness, emotions and spirituality, where religiosity may or may not be an element [29], have also been established in previous research [30]. Spirituality may be defined as a person’s search for meaning and purpose in life and interconnections with others (personal spirituality) using a variety of approaches to attain goals (functional spirituality) [31, 32]. Rowe and Allen found that individuals with a range of chronic illnesses (e.g. diabetes, cancer, chronic back pain and arthritis) who measured high in spirituality also coped better and had a more positive emotional outlook [30]. Quality of life assessments and spirituality are considered to be “inseparable” in chronic condition management [29].

As a consequence of more extensive research examining the application of the Flinders Program, and an even greater depth of practice implementation efforts across more diverse service types and population contexts, the PIH underwent a further revision from the version used to inform the Petkov et al. study [10]. This included the separation of the assessments of impact of chronic illness on social and emotional aspects rather than asking the person to measure them as the same thing. Also, an indicator of empowerment was added to provide a more contemporary assessment of collaborative care where the person is able to negotiate health services relevant to their needs and the health professional helps the person to make “informed choices” [11].

Collaborative care also involves the patient and health professional “meeting in the middle” and “dancing together” in decision-making processes [33, 34]. Shared decision-making (SDM) is an emergent research area where its measurement is comprised mostly of self-report instruments from the patient’s perspective [35]. SDM is commonly promoted in clinical teaching and needs to be facilitated by health professionals in everyday practice in order to achieve empathic care [33, 36–38]. The patient’s “adherence” to a treatment plan perhaps then manifests from a collaborative partnership in which they feel listened to and their perspective respected. This is in contrast to the more traditional care model where non-compliance is perceived as a “personal deficit” of the patient and therefore requiring more expert knowledge and control by the health practitioner [11, 39]. In the current study, we sought to validate the hypothesised factor structure of the revised PIH instrument in an Australian community-based sample of people with chronic conditions.

Methods

Survey methodology

Data were collected from the 2014 South Australian Health Omnibus Survey (HOS), a representative cross-sectional population survey of metropolitan and country areas throughout the State of South Australia [40]. It is conducted annually by a market research organisation and offered as a service to the State’s health organisations. From the statistical area level 1 (SA1s) used as the smallest area of output for the Census of Population and Housing in Australia, people were selected for interviews. On average, SA1s have a population of approximately 400 people (range 200–800 people). In rural and remote areas, the populations are generally lower than in urban areas. [41]. The total population of South Australia is approximately 1.69 million people where 77 % are accounted for by Greater Adelaide, the State’s capital city. For the HOS metropolitan sample, 390 SA1s were selected with their probability of selection proportional to their size. From a randomly selected starting point within each SA1, a “skip pattern” was then used to choose ten households. For the country sample, a similar procedure was used for 130 SA1s but where towns with populations of 10,000 or more were automatically chosen and the balance selected from towns of 1000 or more with their probability of selection proportional to their size.

One interview was conducted per household. The survey was administered face-to-face by trained interviewers with people aged 15 years and over who were selected as the person in the household last to have a birthday. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics committee.

Participant flow

The initial sample drawn for the 2014 HOS was 5200 households. There was a sample loss of 183 households due to vacant houses (including holiday homes), businesses or not permanent tenants. From the sample of 5017 households, 2732 interviews were conducted giving a response rate of 54.5 %. The main reason for non-response was refusal (n = 1323). In addition, 507 initial eligible respondents could not be contacted in spite of up to six visits at different times of day/evening and different days of the week. Thus, the final participation rate was 60.6 %. Of these, 33.1 % (904/2732) responded in the affirmative to the question “Do you have a chronic condition?” and then completed the revised PIH questionnaire. Table 1 shows the demographics of study participants.

Revised Partners in Health scale (PIH)

The original 12-item PIH questionnaire was developed to measure the degree of active involvement of a person to self-manage across a range of chronic conditions. Items in this version are listed in Table 2 based on the previously validated 4-factor structure [10]. The response categories for Items 1–4, 6, 8, 10, 11 and 12 ranged from 0 = Very good to 8 = Very poor; and for Items 5, 7, and 9 from 0 = Always to 8 = Never.

A series of focussed consultations between key clinical groups and Flinders Program team (researchers and education and training providers) during 2009 and 2010 drove the need to revisit the PIH scale. Table 2 presents the revised items in the 12-item PIH scale and proposed factor structure, and the main findings from consultations included the following:

-

1.

A focus group with Flinders-based trainers and research staff and New Zealand Accredited Trainers, held in March 2010, to consider potential changes needed following the release of the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing endorsed expanded national definition of self-management, which flowed from outcomes of an audit of the national primary health care workforce knowledge, skills and confidence to deliver chronic condition self-management support [42]—for “Knowledge” subscale, Item 2 expanded to include medications as part of treatment, Item 3 changed from a focus on taking medications to carrying out treatments including medications; Item 4 expanded to emphasise partnership with health professional(s) and moved to “Partnership in treatment” subscale alongside the new Item 5 in recognition of the need to focus on the person’s ability in collaborating with health professions beyond mere availability of services; items for “Recognition and management of symptoms” subscale were revised to acknowledge that knowing how to keep track of symptoms and signs is different to doing it in practice; Item 11 revised to become Item 10 “emotional impact and spiritual well-being” (well-being derived from intrapersonal processes) and Item 11 “social impact”(well-being derived from interpersonal processes) in recognition that these are different perspectives in relation to coping in practice.

-

2.

A focus group with six Accredited Trainers drawn from services across Australia and New Zealand, held June 2010—advice provided on improving the overall flow in relation to scoring of response categories. These proposed changes were then disseminated electronically to all Flinders Program Accredited Trainers registered on the Flinders database (approximately 80 individuals) on June 2010, seeking their feedback.

-

3.

Further feedback on proposed changes to the PIH scale received at the Flinders Program Accredited Trainers Forum held in Adelaide, November 2010 (n = 40)—final consensus provided on the proposed changes described above and, in particular, the reversal of scoring for response categories (Items 1 and 2, 0 = Very little to 8 = A lot; Items 3–8, 0 = Never to 8 = Always; and Items 9–12, 0 = Not very well to 8 = Very well).

Statistical analysis

The complete sample of 904 survey respondents was used to investigate the a priori PIH 4-factor structure. A bi-factor model was also tested for the potential applicability of a general PIH factor as well as the domain specific factors [43]. Factor models were covariate-adjusted using a person weight variable. For PIH items across 39 interviewers (cluster size = 22.75), 5 of 12 items had design effect values of approximately 2 or greater, indicating that clustering may be substantial enough to bias standard errors [44]. Therefore, a model-based multilevel approach was used to analyse survey data to produce unbiased estimates [45]. A Bayesian confirmatory factor analysis (BCFA) approach was used to test convergent and discriminant validity of the revised PIH [46]. All analyses were conducted using MPlus software (Version 7.3) [47].

BCFA was first used to estimate an “exact” PIH factor model using non-informative prior parameters for the hypothesised major loadings, and non-target parameters were constrained to zero at within- and between-levels. We then repeated the BCFA analysis with the addition of strongly informative priors for cross-loadings at the within-level to “approximate” an exact model. A study sample of Mplus code for an approximate model is provided in Appendix A of ESM. To assess for any further possible improvement in results, cross-loadings found to have 95 % credible intervals not covering zero were freely estimated with non-informative priors in an approximate model and compared to an exact model with the same freely estimated cross-loadings. Model fit was evaluated using posterior predictive p value (PP p) [46]. Final model selection was based on PP p > 0.05 and at the same time being close to an exact BCFA model to better reflect substantive theory. To determine a better-fitting model between an exact BCFA model and approximate BCFA models with varying informative values, deviance information criterion (DIC) was used [48]. A more detailed description of modelling steps is provided in Appendix B of ESM.

To assess the reliability of PIH raw scores at the within-level, McDonald’s omega coefficients and 95 % Bayesian credible intervals were calculated using estimates from the final model [49]. For health status questionnaires, coefficient values between 0.70 and 0.95 are indicative of good internal consistency [50].

Results

Two-level Bayesian confirmatory factor analysis was performed on the PIH 12 items using all available data. Complete PIH records were available for 84.3 % (762/904) of participants. There were 45 missing data patterns across 15.7 % (142/904) of participants where the most common had two or less missing item responses. One case had missing data on all observed variables. Therefore, the final data set for BCFA analysis was comprised of 903 out of 904 cases.

Table 3 presents results from an exact BCFA 4-factor model comprised of non-informative priors for hypothesised major loadings and zero cross-loadings. The posterior predictive p value of almost zero and a positive lower limit of the 95 % confidence interval indicated poor model fit. To evaluate the difference between the exact BCFA model and the data, increasing values of small informative standard deviations for cross-loadings were specified. The approximate model with prior N(0, 0.03) provided an acceptable fit of the data relative to an exact BCFA on the basis of PP p value being close to the postulated threshold of 0.05 and the discrepancy between the observed and replicated chi-square values covered zero. The smaller DIC value inferred higher predictive accuracy for this model compared to the exact model. Potential scale reduction (PSR) values were less than 1.1 and indicated that model convergence had been achieved. The trace plots for each posterior model parameter showed that the chains had converged to their stationary distributions and good mixing had occurred. Histograms of Bayesian posterior parameter distributions were approximately normal. The models with increasing prior values appeared to stabilise at N(0, 0.10) in terms of model fit.

For the BCFA model at N(0, 0.03), two cross-loadings were statistically significant with 95 % Bayesian credibility intervals not covering zero (Item 6: 0.02–0.12; Item 13: 0.01–0.11). To test for a simpler model, the two significant cross-loadings were freely estimated in a model with all other cross-loadings at N(0, 0.03) and then compared to an exact model with the two cross-loadings freely estimated. The exact model showed poorer fit based on PP p < 0.05 and a higher DIC value.

The exact BCFA bi-factor model consisting of a general factor and orthogonal group factors was an unsatisfactory model based on a PP p value close to zero and a positive lower limit for the 95 % confidence interval (Table 3). The addition of small-SD priors for cross-loadings produced satisfactory model fit for values N(0, 0.10). The primary aim of this current study was to identify the best-fitting model for the observed data. The 4-factor model provided a more parsimonious fit of the data with informative prior variances being closer to zero alongside an acceptable PP p value. Clearly, the bi-factor model with prior N(0, 0.10) for cross-loadings could also be used with confidence.

Table 4 shows the within-level factor loadings and factor correlation estimates for the 4-factor exact model and approximate BCFA model at N(0, 0.03). For the approximate BCFA model, 95 % of cross-loading values were specified to lie between −0.06 and +0.06 and actual values ranged from −0.043 to 0.07. In terms of practical measurement application, the differences between an exact BCFA model and approximate BCFA model were mostly due to many unimportant cross-loadings. Therefore, the theorised simple structure in the BCFA model with zero cross-loadings is justified because it shows a realistically close fit, despite its lack of strict fit. All hypothesised factor loadings were substantial and significant at p < 0.001, and factor correlation estimates were in the moderate to large range based on conventional standards [51]. For between (interviewer)-level hypothesised factor loadings, 8 out of 12 were statistically significant and substantial for exact BCFA model (range 0.705–0.971) and approximate BCFA model (range 0.702–0.968). All factor correlations were statistically insignificant at the between-level.

To assess the reliability of subscale scores for the BCFA 4-factor model with small variance priors, McDonald’s omega coefficients were calculated using unstandardised factor loadings and item residual variances. Coefficients (95 % Bayesian credible intervals) for the PIH subscales knowledge, partnership, management and coping were 0.81 (0.78–0.84), 0.68 (0.64–0.71), 0.77 (0.74–0.81) and 0.83 (0.81–0.85), respectively. These values indicated that the subscales reliability in producing raw scores was in the acceptable range for knowledge, management and coping. The coefficient for partnership was just under the cut-off for satisfactory reliability based on recommended values [50].

Discussion

Using PIH data from a representative Australian community survey, Bayesian analyses revealed four related constructs of chronic condition self-management that hold conceptual appeal in line with the practice of chronic condition self-management [5, 6, 52–55]. The difference between the poorly fitting BCFA model with zero cross-loadings and the well-fitting BCFA model with informative priors for cross-loadings was small in an applied context. The substantial degree of correlation between the PIH factors was expected given that self-management is comprised of distinct processes as well as a substantial degree of conceptual unity [11]. These findings provided evidence for PIH convergent and discriminant validity. The four factors were knowledge, partnership, management and coping. The first factor conceptualised the individual’s knowledge of their health condition and treatment. An informed patient is fundamental to achieving optimal chronic care [11]. The second factor was connected to the health practitioner–patient partnership. This construct builds on the previous PIH factor relating to adherence to treatment, for example, “taking medication as prescribed” [10]. The third factor was related to managing and monitoring of symptoms and signs of illness. The primary goal in revising indicators of this factor was to capture the “doing it in practice” aspects of symptom tracking [10]. The fourth factor signified a person’s ability to cope with the physical and mental impact of a chronic condition. The revision of this factor involved the expansion of Item 11 from the original PIH [10] into two separate items (Items 10 and 11) to recognise that a persons’ social (external world) and emotional (internal world) experiences involve different perspectives on coping.

Numerous valuable insights about the role of chronic condition self-management programmes have resulted from research using previous versions of PIH. For example, responses to PIH have shown to be correlated with constructs related to chronic conditions such as mental well-being, general self-efficacy, energy levels, health distress, sense of coherence, hospitalisation rates and perceived efficacy in patient–doctor interactions [6, 52, 56]. It has also been suggested that changes in self-management, as reflected by changes in PIH scores, are the mechanism by which changes in alcohol dependence and co-occurring psychological symptoms occurred in Vietnam veterans who received the Flinders Program of Self-Management Support [5]. The potential of the revised PIH for tapping into similar change processes will require further testing of measurement properties such as criterion-related validity. This would help establish the instruments accuracy in predicting criteria or indicators of self-management constructs relative to its measurement properties found in this study.

While factor analyses of the revised PIH revealed a clear and interpretable structure, two factors consisted of two items. Although from a heuristic perspective our models were identified in accordance with the “two-indicator rule”, three or more indicators per factor have been recommended in order to avoid problems such as under identification and propagation of error to factor loadings [57]. On the other hand, valid instruments with two indicators per factor have been widely published and used in practice [58, 59]. The items were behaviourally anchored and less abstract than cognitively or affectively anchored items, thus lending to the scale’s brevity and clarity in covering the scope of self-management from a generic perspective.

The use of BCFA in this study enabled a flexible approach to exploring the revised PIH factor structure. Nonetheless, a number of areas of this approach require further research, for example, it is not clear how much the posterior predictive p value is influenced by the quantity of variables or observations [46]. Also, whilst early studies have suggested that departures from the multivariate normal assumption do not appear to have a major effect on the p value, further research is still required [46].

A principal strength of this study was the use of a population representative survey methodology to assess structural validity of the revised PIH. Otherwise, the partial breadth of research into PIH measurement properties needs to be addressed. Future research should evaluate other key areas of validity (i.e. hypotheses-testing, content validity and criterion validity), reliability, responsiveness and interpretability [60]. In terms of content validity, the changes made to the revised PIH in this study were conducted with clear measurement aims in the target population and supported by substantive theory. However, a potential limitation was that item selection and rewording was mostly directed through the Flinders clinicians’ experiences with patients. Further developments in PIH need to evaluate the degree to which the items are relevant to and representative of targeted chronic condition self-management concepts using population and expert sampling [50, 61]. Both quantitative and qualitative methods can provide important data for content validation. For example, expert judgements may be quantitatively appraised through formal rating scales and then using a content validity ratio (CVR) statistic to compare with critical values [62, 63]. Also, qualitative interviews or focus groups with patients and experts would further ensure that items are representative of and relevant to self-management constructs [61]. The investigation of the stability of PIH psychometric properties across different types of chronic conditions and risk factors is also needed. This is a necessary pre-condition for any form of group-based comparisons [64, 65]. Such systematic testing of PIH will contribute significantly to much needed quality measures of self-management of behavioural and physical chronic conditions especially for health care organisations focused on “high-cost/high-need patient populations” [1].

In conclusion, the updated Partners in Health scale is a structurally valid instrument for measuring constructs related to self-management of chronic conditions in the Australian general community. This scale may help health professionals to introduce the concept of self-management to their patients and provides a parsimonious assessment of areas of self-management that may lead to interventions targeted to the individual.

References

Goldman, M. L., Spaeth-Rublee, B., & Pincus, H. (2015). Quality indicators for physical and behavioral health care integration. JAMA, 314(8), 769–770. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6447.

Bauer, U. E., Briss, P. A., Goodman, R. A., & Bowman, B. A. (2014). Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: Elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. The Lancet, 384(9937), 45–52.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (2012). Australia’s health 2012. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW. (2011). Key indicators of progress for chronic disease and associated determinants: Data report. Canberra: AIHW.

Battersby, M. W., Beattie, J., Pols, R. G., Smith, D. P., Condon, J., & Blunden, S. (2013). A randomised controlled trial of the Flinders Program™ of chronic condition management in Vietnam veterans with co-morbid alcohol misuse, and psychiatric and medical conditions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(5), 451–462. doi:10.1177/0004867412471977.

Battersby, M., Harris, M., Smith, D., Reed, R., & Woodman, R. (2015). A pragmatic randomized controlled trial of the Flinders Program of chronic condition management in community health care services. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(11), 1367–1375.

Battersby, M. W., Kit, J. A., Prideaux, C., Harvey, P. W., Collins, J. P., & Mills, P. D. (2008). Research implementing the Flinders Model of Self-management Support with Aboriginal people who have diabetes: Findings from a pilot study. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 14(1), 66–74.

Lorig, K. R., Sobel, D. S., Ritter, P. L., Laurent, D., & Hobbs, M. (2000). Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effective Clinical Practice: ECP, 4(6), 256–262.

Battersby, M. W., Ask, A., Reece, M. M., Markwick, M. J., & Collins, J. P. (2003). The Partners in Health scale: The development and psychometric properties of a generic assessment scale for chronic condition self-management. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 9(3), 41–52.

Petkov, J., Harvey, P., & Battersby, M. (2010). The internal consistency and construct validity of the partners in health scale: Validation of a patient rated chronic condition self-management measure. Quality of Life Research, 19, 1079–1085.

Bodenheimer, T., Lorig, K., Holman, H., & Grumbach, K. (2002). Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA, 288(19), 2469–2475.

Pulvirenti, M., McMillan, J., & Lawn, S. (2014). Empowerment, patient centred care and self-management. Health Expectations, 17(3), 303–310. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00757.x.

Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., et al. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ (Clinical Research Edition),. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4163.

Sattoe, J. N., Bal, M. I., Roelofs, P. D., Bal, R., Miedema, H. S., & van Staa, A. (2015). Self-management interventions for young people with chronic conditions: A systematic overview. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(6), 704–715.

Laverack, G. (2009). Public health: Power, empowerment and professional practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Baum, F. (2003). The new public health (Vol. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Camerini, L., Schulz, P. J., & Nakamoto, K. (2012). Differential effects of health knowledge and health empowerment over patients’ self-management and health outcomes: A cross-sectional evaluation. Patient Education and Counseling, 89(2), 337–344.

Lawn, S., Battersby, M., & Pols, R. (2005). National chronic disease strategy—Self-management. Report to the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Adelaide: Flinders Human Behaviour & Health Research Unit, Flinders University.

Barr, P. J., Scholl, I., Bravo, P., Faber, M. J., Elwyn, G., & McAllister, M. (2015). Assessment of patient empowerment—A systematic review of measures. PLoS One, 10(5), e0126553.

Bravo, P., Edwards, A., Barr, P. J., Scholl, I., Elwyn, G., & McAllister, M. (2015). Conceptualising patient empowerment: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 1.

McCorkle, R., Ercolano, E., Lazenby, M., Schulman-Green, D., Schilling, L. S., Lorig, K., et al. (2011). Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 61(1), 50–62. doi:10.3322/caac.20093.

Funnell, M. M., & Anderson, R. M. (2004). Empowerment and self-management of diabetes. Clinical Diabetes, 22(3), 123.

Funnell, M. M., Anderson, R. M., Arnold, M. S., Barr, P. A., Donnelly, M., Johnson, P. D., et al. (1991). Empowerment: An idea whose time has come in diabetes education. The Diabetes Educator, 17(1), 37–41.

Anderson, R. M., & Funnell, M. M. (2010). Patient empowerment: Myths and misconceptions. Patient Education and Counseling, 79(3), 277–282.

Barlow, J., Wright, C., Sheasby, J., Turner, A., & Hainsworth, J. (2002). Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Education and Counseling, 48(2), 177–187.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1988). Unending work and care: Managing chronic illness at home. Los Angeles: Jossey-Bass.

Lorig, K. R., & Holman, H. R. (2003). Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26(1), 1–7.

Schulman-Green, D., Jaser, S., Martin, F., Alonzo, A., Grey, M., McCorkle, R., et al. (2012). Processes of self-management in chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 44(2), 136–144.

Maxine, A. (2006). Spirituality and quality of life in chronic illness. Journal of Theory Construction & Testing, 10(2), 42.

Rowe, M. M., & Allen, R. G. (2003). Spirituality as a means of coping with chronic illness. American Journal of Health Studies, 19(1), 62–66.

Zinnbauer, B. J., Pargament, K. I., & Scott, A. B. (1999). The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality, 67(6), 889–919.

Peterman, A. H., Fitchett, G., Brady, M. J., Hernandez, L., & Cella, D. (2002). Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(1), 49–58.

Elwyn, G., Lloyd, A., May, C., van der Weijden, T., Stiggelbout, A., Edwards, A., et al. (2014). Collaborative deliberation: A model for patient care. Patient Education and Counseling, 97(2), 158–164.

Kon, A. A. (2010). The shared decision-making continuum. JAMA, 304(8), 903–904.

Scholl, I., Koelewijn-van Loon, M., Sepucha, K., Elwyn, G., Légaré, F., Härter, M., et al. (2011). Measurement of shared decision making—A review of instruments. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, 105(4), 313–324.

Barry, M. J., & Edgman-Levitan, S. (2012). Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 780–781.

Makoul, G., & Clayman, M. L. (2006). An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Education and Counseling, 60(3), 301–312.

Singh, S., Butow, P., Charles, M., & Tattersall, M. H. (2010). Shared decision making in oncology: Assessing oncologist behaviour in consultations in which adjuvant therapy is considered after primary surgical treatment. Health Expectations, 13(3), 244–257.

Lawn, S., Delany, T., Sweet, L., Battersby, M., & C Skinner, T. (2014). Control in chronic condition self-care management: How it occurs in the health worker–client relationship and implications for client empowerment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(2), 383–394.

Wilson, D., Wakefield, M., & Taylor, A. (1992). The South Australian health omnibus survey. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 2(3), 47–49.

Australian Bureau of Statisitcs (2015). ASGS fact sheets: Statistical area level 1—Fact sheet. http://www.abs.gov.au/geography. Accessed 26 July 2015.

Lawn, S., & Battersby, M. (2009). Skills for person-centered care—health professionals supporting chronic condition prevention and self-management. In H. M. D’Cruz, S. W. Jacobs, & A. Schoo (Eds.), Knowledge-in-practice in the caring professions: Multi-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 161–192). Surrey: Ashgate.

Chen, F. F., West, S. G., & Sousa, K. H. (2006). A comparison of bifactor and second-order models of quality of life. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 41(2), 189–225.

Muthen, B., & Satorra, A. (1995). Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology, 25, 267–316.

Wu, J.-Y., & Kwok, O.-M. (2012). Using SEM to analyze complex survey data: A comparison between design-based single-level and model-based multilevel approaches. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 19(1), 16–35.

Muthén, B., & Asparouhov, T. (2012). Bayesian structural equation modeling: A more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 313.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus User’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Asparouhov, T., Muthén, B., & Morin, A. J. (2015). Bayesian structural equation modeling with cross-loadings and residual covariances: Comments on Stromeyer et al. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1561–1577.

Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J., & Zyphur, M. J. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 72.

Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., et al. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155.

Warwick, M., Gallagher, R., Chenoweth, L., & Stein-Parbury, J. (2010). Self-management and symptom monitoring among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(4), 784–793.

Kit, J. A. (2003). Chronic disease self-management in Aboriginal communities: Towards a sustainable program of care in rural communities. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 9(3), 168–176.

Gallagher, R., Donoghue, J., Chenoweth, L., & Stein-Parbury, J. (2008). Self-management in older patients with chronic illness. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 14(5), 373–382.

Walters, J., Cameron-Tucker, H., Wills, K., Schüz, N., Scott, J., Robinson, A., et al. (2013). Effects of telephone health mentoring in community-recruited chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on self-management capacity, quality of life and psychological morbidity: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 3(9), e003097.

Heijmans, M., Waverijn, G., Rademakers, J., van der Vaart, R., & Rijken, M. (2015). Functional, communicative and critical health literacy of chronic disease patients and their importance for self-management. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(1), 41–48.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(3), 333–351.

Bruyneel, L., Li, B., Squires, A., Spotbeen, S., Meuleman, B., Lesaffre, E., et al. (2014). Bayesian multilevel MIMIC Modeling for studying measurement invariance in cross-group comparisons. Medical Care. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000164.

Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Stratford, P. W., Knol, D. L., et al. (2010). The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 539–549.

Haynes, S. N., Richard, D., & Kubany, E. S. (1995). Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 238.

Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28(4), 563–575.

Wilson, F. R., Pan, W., & Schumsky, D. A. (2012). Recalculation of the critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 45(3), 197–210.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70.

Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J., Parker, P. D., & Kaur, G. (2014). Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 85–110.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their detailed and helpful comments to the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

As the developer of the Partners in Health (PIH) scale, Author MB has a potential conflict of interest. He has no commercial interests in the PIH.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The study used a cross-sectional population-based survey methodology and did not require formal written consent. All data were de-identified.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, D., Harvey, P., Lawn, S. et al. Measuring chronic condition self-management in an Australian community: factor structure of the revised Partners in Health (PIH) scale. Qual Life Res 26, 149–159 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1368-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1368-5