Abstract

Objective

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) integrates evidence-based interventions to reduce surgical stress and accelerate rehabilitation. Our study was to compare the short-term quality of life (QOL) in patients undergoing open colonic surgery using ERAS program or conventional management.

Methods

A prospective study of 57 patients using ERAS program and 60 patients using conventional management was conducted. The clinical characteristics of all patients were recorded. QOL was evaluated longitudinally using the questionnaires (EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CR29) pre- and postoperatively. Generalized estimating equation was used to do the analysis in order to determine the effective impact of correlative factors on the postoperative QOL, including age, sex, BMI, ASA grade, tumor location, tumor size, pTNM stage, recovery program and length of time after surgery.

Results

The morbidity in ERAS and control group was 17.5 versus 26.7 % (p = 0.235). The patients in ERAS group had much faster rehabilitation and less hospital stay. In the primary statistical analysis, the scores of global QOL (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), physical functioning (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), role functioning (on POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), emotional functioning (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), cognitive functioning (on POD3, POD6) and social functioning (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21, POD28) were higher in ERAS group than in control group, which suggested that the patients in ERAS group had a better life status. However, the scores of pain (on POD10, POD14, POD21), appetite loss (on POD3, POD6), constipation (on POD3, POD6, POD10), diarrhea (on POD3, POD10), financial difficulties (on POD10, POD14, POD21), perspective of future health (on POD6, POD10, POD14), gastrointestinal tract problems (on POD3, POD6, POD10) and defecation problems (on POD6, POD10, POD14) were lower in ERAS group than in control group, which revealed that the patients in ERAS group suffered less symptoms. In the further generalized estimating equation analysis, the result showed that recovery program and length of time after surgery had independently positive impact on the patient’s postoperative QOL.

Conclusion

Short-term QOL in patients undergoing colonic cancer using ERAS program was better than that using conventional management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) or fast track surgery, which combines a series of perioperative interventions, such as no mechanical bowel preparation, no preoperative fasting, and early postoperative feeding, to facilitate early recovery after major surgery by reducing surgical stress and preserving physiological functions, has been popularized in the fields of colorectal surgery [1–4]. Accumulating evidence has validated the safety and effectiveness of the ERAS program in colorectal surgery, compared with the conventional management [5–8]. However, the majority of the available literatures presented the advantage of ERAS only by short-term clinical outcomes, such as morbidity, gastrointestinal recovery, stress responses and hospital stay, and long-term survival [9]. In addition, quality of life (QOL) has been advocated to assess cancer therapy [10]. Currently, the most widely used tool for the assessment of QOL in colonic cancer is established by European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. It consists of QLQ-C30 (core module) and QLQ-CR29 (colonic cancer-specific module). Several clinical trials accomplished have proved the feasibility, reliability and validity to assess QOL of patients with colonic cancer pre- or postoperation [11–13]. However, there are few literatures on the influence of ERAS protocols and QOL, and no evidence that ERAS adversely affect QOL or patient satisfaction [14].

The aim of our prospective non-randomized controlled trial was to discover the difference between the short-term QOL of patients undergoing colonic surgery using ERAS program or conventional perioperative management, together with perioperative clinical outcomes.

Patients and methods

Study design

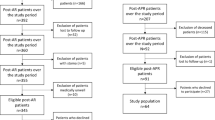

ERAS program has been introduced in our hospital from 2007. From 2012, we prospectively enrolled patients who underwent colonic surgery by the same surgical group and asked them to complete the QOL questionnaire. This prospective trial was approved by the Ethical Committee of Medicine, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University. All patients provided written informed consent. At last, a total of 117 patients were enrolled in this prospective study from July 2012 to October 2013.

Perioperative treatment of the ERAS and control groups

All the patients underwent radical resection of colonic cancer via laparotomy by the same surgical group. The details of perioperative elements of ERAS program or conventional perioperative management have been published elsewhere [15]. The ERAS program consists of no mechanical bowel preparation, no preoperative fasting, early postoperative feeding, restrictive intravenous fluids, early mobilization and other regimens. And the discharge criteria include good pain control with oral analgesia, ability to take solid food, no intravenous fluids, independently mobilization and be suitable for going home.

The questionnaires and QOL assessment

QOL was the primary outcome of the planned study. The assessment of QOL was based on a previously validated cancer-specific core questionnaire, QLQ-C30 (version 3.0, in Chinese) and the colonic cancer-specific module QLQ-CR29 (in Chinese, translated from English version) both developed by EORTC. The QLQ-C30 module is composed of one global QOL scale, five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social), nine symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties). Each scale contains one or several questions. And each question has four response alternatives: “not at all” (scored as 1), “a little” (scored as 2), “quite a bit” (scored as 3) and “very much” (scored as 4), except for the global QOL scale which ranges from “very poor” (scored as 1) to “excellent” (scored as 7) [16]. The QLQ-CR29 module includes two functional scales (body image and future health perspective) and five symptoms scales (micturition problem, gastrointestinal problem, defecation problems, sexual problems and chemotherapeutic-related problem). This module has the same four response alternatives as QLQ-C30 [17].

All patients filled out the questionnaires before operation and at the follow-up (postoperation day 3 (POD3), POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21 and POD28) by letter visit or outpatient consultant. Due to the observing time, the investigation of scales about chemotherapy or sexual problem in the CR-29 was not carried out.

Statistic analysis

Demographic data were compared using t test, Mann–Whitney U test or Chi-square test as appropriate. Scores, derived from the questionnaires, were linearly transformed into a 0–100 scale according to the EORTC Scoring Manual [16, 17]. A higher score in the functional or global QOL scales represented a higher level of function and better global QOL, whereas a higher score in symptom scales or items indicated more severe symptoms. Then, the changed scores of QOL on POD3/6/10/14/21/28 (in comparison with pre-operation) were calculated, respectively. According to the EORTC guidelines document [18], a change of 5–10 points (on the 0–100 scale) for the score of QOL denotes a clinically significant change of “little better (or worse),” a change of 10–20 points as “moderate better (or worse)” and a change greater than 20 as “very much better (or worse).” All data analyses were performed by using SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Mean scores and standard deviations were calculated. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine statistical significance at the 5 % level for the difference of QOL scores between the two groups. p value of <0.05 was regarded as significance and <0.01 as prominent significance. Furthermore, we used generalized estimating equation to do the longitudinal data analysis in order to determine the effective impact of correlative factors on the postoperative QOL, including age, sex, BMI, ASA grade, tumor location, tumor size, pTNM stage, recovery program and length of time after surgery. The analysis was done using R 3.0.1.

Results

Demography of the patients

The two groups were comparable with respect to clinical characteristics. There was no significant difference between the two groups in age, gender, body mass index, ASA grade, tumor location, tumor size or TNM stage (Table 1).

Perioperative outcomes

There was no mortality in the two groups. The morbidity was 17.5 % in ERAS group and 26.7 % in conventional group, with no significant difference (Table 2). However, the patients in ERAS groups had faster rehabilitation: first time out of bed (15.3 ± 3.64 vs. 42.5 ± 14.7 h, p < 0.001), first time of flatus (60.9 ± 11.1 vs. 74.2 ± 16.3 h, p < 0.001) and first time of bowel movement (75.1 ± 14.9 vs. 85.5 ± 19.4 h, p = 0.002). In addition, the postoperative hospital stay was much shorter in ERAS group (6.1 ± 1.7 vs. 8.7 ± 2.8 day, p < 0.001).

Comparison of QOL

The response of the QOL measure was about 96 % in total during the entire follow-up period (96.2 % [384/399] of questionnaires were fed back in the ERAS group and 95.2 % [400/420] in the control group). The missing data were two on POD3, two on POD6, three on POD10, one on POD14, two on POD21, five on POD28 in ERAS group, while three on POD3, four on POD6, two on POD10, five on POD14, two on POD21, four on POD28 in control group.

In the primary statistical analysis, the scores of global QOL (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), physical functioning (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), role functioning (on POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), emotional functioning (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21), cognitive functioning (on POD3, POD6) and social functioning (on POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21, POD28) were higher in ERAS group than in control group, which suggested that the patients in ERAS group had a better life status (Table 3). However, the scores of pain (on POD10, POD14, POD21), appetite loss (on POD3, POD6), constipation (on POD3, POD6, POD10), diarrhea (on POD3, POD10), financial difficulties (on POD10, POD14, POD21), perspective of future health (on POD6, POD10, POD14), gastrointestinal tract problems (on POD3, POD6, POD10) and defecation problems (on POD6, POD10, POD14) were lower in ERAS group than in control group, which revealed that the patients in ERAS group suffered less symptoms (Table 3).

In the further generalized estimating equation analysis, the result showed that recovery program and length of time after surgery had independently positive impact on the patients’ postoperative QOL (in the items of global QOL, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, gastrointestinal tract problems and defecation problems; Table 4).

Discussion

The research focusing on QOL of ERAS program, especially in the early postoperative period, is required. This study shows that the ERAS group has faster rehabilitation, fewer hospital stay and no increased morbidity, which is in accordance with previous reports, and ERAS could improve the short-term QOL in patients undergoing colonic resection.

ERAS program could hasten recovery of the physical and mental function in the postoperative period compared with conventional management. Gatt et al. [19] measured the hand-grip strength preoperatively and postoperatively to assess the recovery of physical function in patients undergoing major colonic resection and found that the hand-grip strength was maintained throughout the observation period in the ERAS group, but was significantly reduced in conventional group. Besides, the mental function of patients is seldom used to evaluate the clinical outcome because it is determined subjectively and usually difficult to reflect. However, it is actually important for patients, especially during the period of enduring a major surgery.

A few studies have examined the influence of ERAS protocols and QOL. Anderson et al. [20] observed that ERAS was associated with significantly lower pain scores at rest, on movement and on coughing, on POD1, and lower fatigue scores on POD7. Basse et al. [21] also demonstrated that patients with ERAS program were with less pain at rest on POD1 and POD2. Raue et al. [22] evaluated that visual analog scale scores for pain were similar for the two groups, but fatigue was increased in the standard-care group on POD1 and POD2. Jakobsen et al. [23] found that patients with ERAS program regained functional capabilities earlier with less fatigue and need for sleep compared with those having conventional care. Zargar-Shoshtari et al. [24] demonstrated that postoperative fatigue significantly increased in both groups, and peak fatigue score, the total fatigue experience and the total fatigue impact were significantly lower in the ERAS group. However, Delaney et al. [25] observed that the pain scores at the time of discharge were higher in ERAS patients, and the role emotional and mental health scores were significantly reduced in ERAS patients at discharge. In contrast, Gatt et al. [19] and Henriksen et al. [26] documented that there were no differences in pain or fatigue scores postoperatively between the groups, and King et al. [27] and Khan et al. [28] proved that there were no significant differences in QOL or health economic outcomes between the two groups. Our result showed that the patients in ERAS group had better status on role, emotional and social function in the early postoperative period than those in the control group. As patients generally have severe psychological burden of surgery, faster recovery to daily life is crucial to overcome the depression and return to a promising mental status.

In addition, this result showed that gastrointestinal tract problem and defecation problem meliorated to normal level much faster in the ERAS group than that in the conventional group. It can probably be attributed to perioperative nutrition support and early mobilization, which could reduce gastrointestinal stress response and accelerate the recovery of bowl movement.

In the present study, a faster recuperation after colonic surgery may bring the patients a better subjective feelings and satisfaction. Therefore, the score of global QOL scale in ERAS group was higher than control group (POD3, POD6, POD10, POD14, POD21). However, the scores of the two groups tended to closer in the follow-up (POD28), which might indicate that the difference between two perioperative management only manifest during a short term after surgery. And a recent systematic review often publications also concluded beyond 30 days after surgery; none of the QOL measures showed any differences [14]. Moreover, some patients in this study would receive adjunctive chemotherapy which would add much more influence on the QOL. Therefore, the observation endpoint time of this study was set on just 1 month after surgery.

However, the differences of QOL scores usually lack a clinical interpretation until the advent of some evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores [29, 30]. With the help of those guidelines, we more accurately interpret QOL differences. In our study, the significant differences of physical functioning and social functioning are likely to be median improvements, the differences of global QOL in POD21 and POD28 are trivial improvements, and other differences are small improvements.

Whether the ERAS could be universally applied is an important issue. As it is advocated and popularize mainly in Europe and North America, some researchers may doubt whether ERAS could be feasible in eastern countries. Our previous study has proved its feasibility [15]. In addition, in this series, 95 % of the patients fulfilled the entire ERAS program and presented a better perioperative outcome and QOL. Therefore, as to our experience, ERAS could also be suitable for Chinese patients, in despite of the diversity of race and custom.

In summary, this study showed that the short-term QOL in patients undergoing colonic resection using ERAS program was better than that using conventional management. These results may provide another descriptive dimension for the recommendation of ERAS in the surgery of colonic cancer. However, the main limitation of this study was the single institution participated and non-randomized. Besides, the patient’s self-reported components were subjective data, which may be inhomogeneous. And all these would lead to bias. Therefore, further randomized controlled studies from multiple centers are necessary to confirm these findings.

References

Basse, L., Hjort Jakobsen, D., Billesbølle, P., et al. (2000). A clinical pathway to accelerate recovery after colonic resection. Annals of Surgery, 232, 51–57.

Kehlet, H., & Wilmore, D. W. (2002). Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. American Journal of Surgery, 183, 630–641.

Fearon, K. C., Ljungqvist, O., Von Meyenfeldt, M., et al. (2005). Enhanced recovery after surgery: A consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clinical Nutrition, 24, 466–477.

Lassen, K., Soop, M., Nygren, J., et al. (2009). Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) GROUP recommendations. Archives of Surgery, 144, 961–969.

Wind, J., Polle, S. W., Fung Kon Jin, P. H., et al. (2006). Systematic review of enhanced recovery programmes in colonic surgery. British Journal of Surgery, 93, 800–809.

Spanjersberg, W. R., Reurings, J., Keus, F., et al. (2011). Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2, CD007635.

Vlug, M. S., Wind, J., Hollmann, M. W., et al. (2011). Laparoscopy in combination with fast track multimodal management is the best perioperative strategy in patients undergoing colonic surgery: A randomized clinical trial (LAFA-study). Annals of Surgery, 254, 868–875.

Zhuang, C. L., Ye, X. Z., Zhang, X. D., et al. (2013). Enhanced recovery after surgery programs versus traditional care for colorectal surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 56, 667–678.

Koller, M., & Lorenz, W. (2003). Survival of the quality of life concept. British Journal of Surgery, 90, 1175–1177.

Langenhoff, B. S., Krabbe, P. F., Wobbes, T., et al. (2001). Quality of life as an outcome measure in surgical oncology. British Journal of Surgery, 88, 643–652.

Otto, S., Kroesen, A. J., Hotz, H. G., et al. (2008). Effect of anastomosis level on continence performance and quality of life after colonic J-pouch reconstruction. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 53, 14–20.

Sailer, M., Fuchs, K. H., Fein, M., & Thiede, A. (2002). Randomized clinical trial comparing quality of life after straight and pouch coloanal reconstruction. British Journal of Surgery, 89, 1108–1117.

Kasparek, M. S., Hassan, I., Cima, R. R., et al. (2011). Quality of life after coloanal anastomosis and abdominoperineal resection for distal rectal cancers: Sphincter preservation vs quality of life. Colorectal Disease, 13, 872–877.

Khan, S., Wilson, T., Ahmed, J., et al. (2010). Quality of life and patient satisfaction with enhanced recovery protocols. Colorectal Disease, 12, 1175–1182.

Ren, L., Zhu, D., Wei, Y., et al. (2012). Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program attenuates stress and accelerates recovery in patients after radical resection for colorectal cancer: A prospective randomized controlled trial. World Journal of Surgery, 36, 407–414.

Fayers, P. M., Aaronson, N. K., Bjordal, K., et al. (2001). The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual (3rd edition). Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Whistance, R. N., Conroy, T., Chie, W., et al. (2009). Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to Assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 45, 3017–3026.

Osoba, D., Rodrigues, G., Myles, J., et al. (1998). Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16, 139–144.

Gatt, M., Anderson, A. D., Reddy, B. S., et al. (2005). Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization of surgical care in patients undergoing major colonic resection. British Journal of Surgery, 92, 1354–1362.

Anderson, A. D. G., McNaught, C. E., MacFie, J., et al. (2003). Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization and standard perioperative surgical care. British Journal of Surgery, 90, 1497–1504.

Basse, L., Raskov, H. H., Hjort Jakobsen, D., et al. (2002). Accelerated postoperative recovery programme after colonic resection improves physical performance, pulmonary function and body composition. British Journal of Surgery, 89, 446–453.

Raue, W., Haase, O., Junghans, T., et al. (2004). ‘Fast-track’ multimodal rehabilitation program improves outcome after laparoscopic sigmoidectomy: A controlled prospective evaluation. Surgical Endoscopy, 18, 1463–1468.

Jakobsen, D. H., Sonne, E., Andreasen, J., et al. (2006). Convalescence after colonic surgery with fast-track vs conventional care. Colorectal Disease, 8, 683–687.

Zargar-Shoshtari, K., Paddison, J. S., Booth, R. J., et al. (2009). A prospective study on the influence of a fast-track program on postoperative fatigue and functional recovery after major colonic surgery. Journal of Surgical Research, 154, 330–335.

Delaney, C. P., Zutshi, M., Senagore, A. J., et al. (2003). Prospective, randomized, controlled trial between a pathway of controlled rehabilitation with early ambulation and diet and traditional postoperative care after laparotomy and intestinal resection. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 46, 851–859.

Henriksen, M. G., Jensen, M. B., Hansen, H. V., et al. (2002). Enforced mobilization, early oral feeding, and balanced analgesia improve convalescence after colorectal surgery. Nutrition, 18, 147–152.

King, P. M., Blazeby, J. M., Ewings, P., et al. (2006). The influence of an enhanced recovery programme on clinical outcomes, costs and quality of life after surgery for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Disease, 8, 506–513.

Khan, S. A., Ullah, S., Ahmed, J., et al. (2013). Influence of enhanced recovery after surgery pathways and laparoscopic surgery on health-related quality of life. Colorectal Disease, 15, 900–907.

Osoba, D., Hsu, M. A., Copley-Merriman, C., et al. (2006). Stated preferences of patients with cancer for health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) domains during treatment. Quality of Life Research, 15, 273–283.

Cocks, K., King, M. T., Velikova, G., et al. (2012). Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European organisation for the research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30. European Journal of Cancer, 48, 1713–1721.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Hao Wang, Dexiang Zhu and Li Liang have contributed equally to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Zhu, D., Liang, L. et al. Short-term quality of life in patients undergoing colonic surgery using enhanced recovery after surgery program versus conventional perioperative management. Qual Life Res 24, 2663–2670 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0996-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0996-5