Abstract

Purpose

To assess the procedures of translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and measurement properties of breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaires.

Methods

Searches were conducted in the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and SciELO using the keywords: “Questionnaires,” “Quality of life,” and “Breast cancer.” The studies were analyzed in terms of methodological quality according to the guidelines for the procedure of cross-cultural adaptation and the quality criteria for measurement properties of questionnaires.

Results

We found 24 eligible studies. Most of the articles assessed the translation and measurement properties of the instrument EORTC QLQ-BR23. Description about translation and cross-cultural adaptation was incomplete in 11 studies. Translation and back translation were the most tested phases, and synthesis of the translation was the most omitted phase in the articles. Information on assessing measurement properties was provided incompletely in 23 articles. Internal consistency was the most tested property in all of the eligible articles, but none of them provided information on agreement. Construct validity was adequately tested in only three studies that used the FACT-B and QLQ-BR23. Eight articles provided information on reliability; however, only four found positive classification. Responsiveness was tested in four articles, and ceiling and floor effects were tested in only three articles. None of the instruments showed fully adequate quality.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence on cross-cultural adaptations and measurement properties; therefore, it is recommended that caution be exercised when using breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaires that have been translated, adapted, and tested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization estimates that by the year 2030, there will be 27 million new cases of cancer, 17 million deaths from cancer, and 75 million people living with cancer each year. The greatest effect of this increase will be felt in underdeveloped and developing countries [1]. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women. The global incidence has increased from 641,000 cases in 1980 to 1,643,000 cases in 2010, a yearly growth rate of 3.1 % [2].

A breast cancer diagnosis brings great anxiety and distress, and during surgical or conservative treatment, the patient can suffer physical limitations such as reduced shoulder movement and psychological changes such as depression and low self-esteem [1, 3–5]. Considering the high incidence of breast cancer and the effect that it can have on women’s lives, greater emphasis has been placed on the research on quality of life of women with breast cancer in the last few years [6, 7].

Quality-of-life assessment has become more prominent as a measurement of the results of treatment in medicine. It is basically conducted by administering questionnaires, most of them written in English and geared toward an English-speaking audience. Quality-of-life assessment in cancer has also followed that trend and today a large number of specific questionnaires can be found in the literature, such as the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-BR23) [8], the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B), and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast plus Arm Morbidity (FACT-B+4) [9], among others. However, for these questionnaires to be used in a language other than the source language, they must be translated and cross-culturally adapted into a new equivalent version of the original questionnaire.

The aim of the cross-cultural adaptation process is to produce a new version that is semantically and idiomatically equivalent to the original version [10]. Because of language and cultural difference, a simple translation is not sufficient [10]. To this date, there are several existing guidelines [11–13] describing an adequate procedure of translation and adaptation of measurement instruments. However, after the cross-cultural adaptation, it is crucial to test the psychometric properties of the adapted questionnaire in the target population to ensure that the new version is reproducible, valid and responsive [12, 14–16].

It is clear that there is an increasing number of questionnaires that assess quality of life in breast cancer. However, choosing a questionnaire can be difficult due to the methodological gaps and deficiencies in the processes of translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and assessment of measurement properties. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were: (1) to identify, through a systematic review, the breast cancer-specific questionnaires that have been cross-culturally adapted and (2) to critically analyze the quality of the translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and evaluation of measurement properties of the versions found in the literature.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the analysis, the studies had to assess breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaires translated into a language other than the source language without restriction of year or language of publication and applied exclusively to women with breast cancer. Studies were excluded if they were duplicated in another database, if the title and abstract were not related to the topic, or if the questionnaires were in the source language. We also excluded notes or letters from the editor, systematic reviews, conference papers, books, dissertations and theses, as well as articles not found in libraries or not provided by the authors after email contact.

Search strategy

The search for articles was performed in the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and SciELO. The terms used in the search were based on the MeSH descriptors in English and DeCS in Portuguese. For example, in the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL, some of the terms used were: “Questionnaires,” “Quality of life,” “Breast cancer,” “Translate,” “Validity,” and “Cross-cultural.” In SciELO, the terms were: “Questionários,” “Qualidade de vida,” and “Câncer de mama.” The terms were interconnected by the search operators “OR” and “AND.” The only limit used was “Human.” A detailed description of the search strategy is provided in “Appendix.” First, the resulting studies were analyzed based on the information in the title and abstract, and then, the remaining studies were read in full. The last search date was June 20, 2013.

Data extraction and methodological quality assessment of eligible studies

The description of the analyzed studies included language, year of publication, time of application and sample size. Data were extracted to describe all cross-cultural adaptation procedures (i.e., how the translation procedures were performed) and all measurement properties from each included study. Additionally, the translation, cross-cultural adaptation procedures, and the measurement properties were rated by the Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measure [12] and by the Quality Criteria for Psychometric Properties of Health Status Questionnaire [14], respectively. All the data extraction was conducted independently by two assessors, and the assessment of the methodological quality was determined by consensus.

The process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation evaluated in this study included initial translation, synthesis of translation, followed by the back translation, expert committee review, and test of pre-final version. The measurement properties evaluated in this study were data quality (ceiling and floor effects), construct validity, internal consistency, reproducibility (agreement and reliability), and responsiveness. These procedures are described with more detail in Table 1.

Both the Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measure [12] and the Quality Criteria for Psychometric of Health Status Questionnaire [12] not only evaluate the quality of the translation, adaptation, and the evaluation of each measurement properties but also the methodological quality of each included study, such as number of translators required, adequate sample size, test–retest interval, and others (Table 2). This methodological quality has already been used in previous systematic reviews [17, 18].

Results

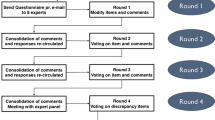

A total of 2,561 studies were found in the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and SciELO. Four [19–22] of those studies would have been eligible because they included the relevant information in their abstracts; however, they were not found in libraries and were not provided by the authors after a request was sent by email. Therefore, only 24 articles assessed quality-of-life questionnaires that specifically evaluated breast cancer (Fig. 1). Most of the articles (13 in all) assessed the translation and measurement properties of the instrument EORTC QLQ-BR23, and eight articles assessed the FACT-B. Of the 24 eligible articles, 11 contained some information on the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation and 23 contained information on the assessment of measurement properties, with 10 containing information on both the translation and adaptation process and the measurement property assessment.

Table 3 summarizes the analyzed studies and characteristics related to the language and year of publication, measurement properties examined in each study, time of application and sample size. Table 4 shows the list of six breast cancer-specific questionnaires assessed according to the guidelines for translation and cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires [12]. Translation and back translation were the most tested stages, with 10 articles [23–32] completing these parts of the translation process. In contrast, synthesis of the translation was the least frequent stage, having been described by only four articles [23, 24, 28, 31]. More than half of the articles, 14 in all [33–46], used translated versions of the instruments, but did not provide information on the stages of translation and cross-cultural adaptation.

Regarding the languages of the new versions of the breast cancer-specific instruments, the most common was Chinese, with five articles [38, 42–45]. However, none of these articles included information on the process of translation. There were also versions in German [24, 25] and in Indian languages [28, 29]. The EORTC QLQ-BR23 was the instrument with the most cross-cultural adaptations and the most tested measurement properties.

Regarding the measurement properties, Table 5 shows a list of the 24 articles (6 questionnaires) analyzed according to the criteria proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires [14]. Internal consistency was the most tested property in all of the eligible articles and showed doubtful classification in 15 articles [25, 26, 28, 32–35, 37–43, 46]. In contrast, no information was found on agreement. Construct validity was adequately tested in three studies [29, 31, 41] that used the FACT-B [31] and the EORTC QLQ-BR23 [29, 41]. Reliability results were obtained from eight articles [33, 35, 38, 39, 42–45], with four showing positive classification [35, 38, 42, 44]. Of these, three articles [39, 43, 45] measured reliability using correlation and, despite the acceptable design, were classified as questionable [39, 43, 45], and only one article [33] showed negative classification, with intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) <0.7. Responsiveness was tested in four articles [23, 27, 30, 36], and ceiling and floor effects were tested in only three articles [33, 35, 41].

Discussion

The present study investigated the process of translation and measurement properties and assessed the translation and adaptation procedures and measurement properties of breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaires. Most of the studies assessed the instrument EORTC QLQ-BR23. Based on the data for methodological quality, it is clear that the breast cancer-specific instruments with the most tested translations and measurement properties were the FACT-B and EORTC QLQ-BR23.

This review was based on current, internationally recognized guidelines [12, 14]. However, it is worth noting that there are other methods of assessing translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and measurement properties that do not include all of the stages tested in the present study, such as in the recommendations of the EORTC (European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer) followed by some of the articles. Indeed, Hui and Triandis proposed a dimension for cross-cultural validation [47, 48]. They postulated four dimensions of equivalence when attempting to internationally measure a construct such as quality of life. These dimensions are functional equivalence (adequacy of translation), scale equivalence (comparability of response scales), operational equivalence (standardization of psychometric testing procedures), and metric equivalence (transferability of scoring results from one culture to another) [47, 48]. Cross-cultural validation and measurement properties of a quality-of-life questionnaire are very difficult to be handled even at present. The current, internationally recognized guidelines [12, 14] are critical and useful to estimate functional equivalence and operational equivalence, but not perfect ones, because it is difficult to investigate scale equivalence and metric equivalence. Namely, there is still no perfect method (gold standard) for cross-cultural validation, and researches around these issues are still going on.

Considering translation and cross-cultural adaptation, only 11 articles [23–32, 40] described this methodological process, and none of the questionnaires showed a complete description of the quality. The FACT-B was incompletely assessed in four of the articles included in this study. Deficiencies in the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation were observed on all the stages [24, 28, 31, 40]. The EORTC QLQ-BR23 was described by seven articles included in this study [23, 25–27, 29, 30, 32]. The cross-cultural adaptations of this instrument followed the recommendations of the EORTC [15–17, 19, 20, 22]; however, only five articles [23, 26, 29, 30, 32] included some description of these adaptations. Despite this description, the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the EORTC QLQ-BR23 was incomplete in all the studies. The eligible studies that evaluated the other questionnaires included in this systematic review (FACT-B+4, IBCSG, LSQ-32 and QLICP-BR) did not provide any information about the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation.

Regarding year of publication, 20 studies [23–26, 28, 29, 31–36, 38, 40–46] were published after the year 2000, when the guidelines for translation and cross-cultural adaptation were published [12]; however, none of the studies followed precisely the recommendations already available in the literature. Additionally, 14 studies [33–46] did not provide any information related to the translation. As none of the studies followed the guidelines, it is difficult to apply the translated questionnaire in a breast cancer population, because there is no guarantee that this questionnaire is semantically and idiomatically equivalent to the original version [10].

In the assessment of measurement properties, 23 articles included some information on breast cancer questionnaires, but none of them tested all of the measurement properties. The criteria for measurement properties were published in 2007 [14]; however, 13 of the articles [24, 27–32, 36–39, 43, 45] included in this systematic review were published in 2007 or previous years. This explains the large number of inadequate or incomplete analyses in these studies. Still, 11 articles [23, 25, 26, 33–35, 40–42, 44, 46] were published after the criteria were published, and none of them followed the steps adequately and thoroughly, suggesting a lack of interest by the researchers in conducting high methodological quality studies.

The internal consistency of the questionnaire EORTC QLQ-BR23 received a doubtful or negative classification in all the eligible studies [23, 25–27, 29, 30, 32–34, 38, 41, 43, 46] because this property has not been adequately assessed in accordance with the guidelines. This classification is usually due to the absence of factor analysis or an insufficient sample size. The evaluation of factor analysis is important to determine the dimensionality of a questionnaire and consequently affects the internal consistency of an instrument [14]. Construct validity was classified as positive in two studies [29, 41]. In these two studies, the authors formulated hypotheses, described them in their methods, and at least 75 % of the results were within the expected values [14]. These hypotheses are essential and must be specified, since it would be easier to explain the low correlations than to conclude that the questionnaire is not valid [14].

The aim of this review is to fully analyze reproducibility through reliability and agreement, but although agreement is easy to interpret because it is expressed in the instruments’ measurement units, the eligible studies only tested reliability. Reliability of the EORTC QLQ-BR23 was classified as positive in only one study [38]. Responsiveness and floor and ceiling effects received a doubtful or negative classification. For the questionnaire FACT-B, the same scenario is observed. Only one translated version received a positive classification for reliability [42]. In the same way, a translated version of FACT-B+4 and of QLICP-BR received a positive classification for reliability [35, 44], and a translated version of the questionnaire IBCSG received a positive classification for responsiveness [36].

After analyzing all of the articles and the quality classification of the translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and measurement properties, we can conclude that there is a deficiency in the methodological quality of the breast cancer instruments used around the world as a result of inadequate testing and assessment of translation, adaptation, and measurement properties. The choice of the best breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire depends on attending explicit quality criteria that was evaluated in this systematic review [14]. In some cases, the translated version can show different measurement properties than that observed in the original version, because of the existence of cultural differences between distinct populations. Therefore, new studies are needed to fully assess these measurements in a clear and adequate fashion so that the best instrument can be used in this population. Other systematic reviews assess the same criteria as the present study in other instruments and confirm the presence of methodological deficiencies [17, 18, 49–51].

Other studies that assessed the measurement properties and cross-cultural adaptations of breast cancer quality-of-life questionnaires [50, 52] used different forms of assessment and some methodological aspects that need improvement that was also in the present study. For example, the assessment of internal consistency must be improved, the assessment of construct validity must be related to pre-defined hypotheses, reliability must be calculated using acceptable measurements such as ICC and Kappa, and the process of translation must be reviewed to avoid low methodological quality that could affect the validity of the questionnaire. The main limitation of our study was the loss of some articles that might have contained important information, but that were excluded because they were not found in libraries and were not provided by the authors, despite request via email.

This systematic review aimed to follow the internationally recommended guidelines for translation and cross-cultural adaptation and for measurement property testing, as well as show the importance of conducting tests adequately to determine the best instrument to be used in clinical practice or scientific research. In conclusion, the available evidence on measurement properties and cross-cultural adaptations is very limited; therefore, it is recommended that caution be exercised when using breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaires that have been translated, adapted, and tested. Finally, studies with high methodological quality are necessary to compensate for the insufficient and inadequate assessment of cross-cultural adaptations and measurement properties.

References

Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional do Câncer. (2011). Estimativas/2012 incidência de câncer no Brasil. Retrieved February 01, 2013, from http://www.inca.gov.br/estimativa/2012/estimativa20122111.pdf.

Forouzanfar, M. H., Foreman, K. J., Delossantos, A. M., Lozano, R., Lopez, A. D., Murray, C. J. L., et al. (2011). Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1461–1484.

Hwang, J. H., Chang, H. J., Shim, Y. H., Park, W. H., Park, H., Huh, S. J., et al. (2008). Effects of supervised exercise therapy in patients receiving radiotherapy for breast cancer. Yonsei Medical Journal, 49(3), 443–450.

Springer, B. A., Levy, E., McGarvey, C., Pfalzer, L. A., Stout, N. L., Gerber, L. H., et al. (2010). Pre-operative assessment enables early diagnosis and recovery of shoulder function in patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 120(1), 135–147.

Petito, E. L., & Gutiérrez, M. G. R. (2008). Elaboração e validação de um programa de exercício para mulheres submetidas a cirurgia oncológica de mama. Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia, 54(3), 275–287.

Lotti, R. C. B., Barra, A. A., Dias, R. C., & Maklufz, A. S. D. (2008). Impacto do Tratamento de Câncer de Mama na Qualidade de Vida. Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia, 54(4), 337–367.

Sandgren, A. K., Mullens, A. B., Erickson, S. C., Romanek, K. M., & McCaul, K. D. (2004). Confidant and breast cancer patient reports of quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 13(1), 155–160.

Pais-Ribeiro, J., Pinto, C., & Santos, C. (2008). Validation study of the portuguese version of the QLC-C30-V.3. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 9(1), 89–102.

Brady, M. J., Cella, D. F., Mo, F., Bonomi, A. E., Tulsky, D. S., Lloyd, S. R., et al. (1997). Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 15(3), 974–986.

Terwee, C. B., D.V.H., Bouter, L. M., Stratford, P. W., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., et al. (2014). Consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments—COSMIN 2013. Retrieved June 01, 2014, from http://www.cosmin.nl/.

Koller, M., Aaronson, N. K., Blazeby, J., Bottomley, A., Dewolf, L., Fayers, P., et al. (2007). Translation procedures for standardised quality of life questionnaires: The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) approach. European Journal of Cancer, 43(12), 1810–1820.

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 25(24), 3186–3191.

Bullinger, M., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Leplege, A., Sullivan, M., Wood-Dauphinee, S., et al. (1998). Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA Project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 913–923.

Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A. W. M., Knola, D. L., Dekkera, J., et al. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42.

De Vet, H. C., Terwee, C. B., Mokkink, L. B., & Knol, D. L. (2011). Measurement in medicine: A practical guide. New York: Cambrigde University Press.

Streiner, D. L., & Norman, G. R. (2008). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

da Menezes Costa, L. C., Maher, C. G., McAuley, J. H., & Costa, L. O. (2009). Systematic review of cross-cultural adaptations of McGill Pain Questionnaire reveals a paucity of clinimetric testing. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(9), 934–943.

Puga, V. O. O., Lopes, A. D., & Costa, L. O. P. (2012). Assessment of cross-cultural adaptations and measurement properties of self-report outcome measures relevant to shoulder disability in Portuguese: A systematic review. Revista Brasileira de Fisioterapia, 16(2), 85–93.

Yang, Z., Tang, X. L., Wan, C. H., Zou, T. N., Chen, D. D., Zhang, D. M., et al. (2007). Development of the system of quality of life instruments for patients with breast cancer (QLICP-BR). Ai Zheng, 26(10), 1122–1126.

Condón Huerta, M. J., González Viejo, M. A., Tamayo Izquierdo, R., & Martínez Zubiri, A. (2000). Calidad de vida en pacientes con y sin linfedema despúes del tratamiento del cáncer de mama: Implicaciones en la rehabilitación. Rehabilitación, 34(3), 248–253.

Mihailova, Z., Antonov, R., Toporov, N., & Popova, V. (2001). Evaluation of the Bulgarian version of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30 (version 2) and breast cancer module (BR23) on the psychometric properties of breast cancer patients under adjuvant chemotherapy. Prognostic value of estrogen and progesterone receptors to quality of life. Journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology, 6(4), 415–424.

Yang, P., & Lu, Q. (2009). Investigation on quality of life status of breast cancer patients after operation in follow-up period. Chinese Nursing Research, 23(5A), 1150–1153. (Chinese).

Cerezo, O., Onate-Ocana, L. F., Arrieta-Joffe, P., Gonzalez-Lara, F., Garcia-Pasquel, M. J., Bargallo-Rocha, E., et al. (2012). Validation of the Mexican-Spanish version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR23 questionnaires to assess health-related quality of life in Mexican women with breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care (Engl), 21(5), 684–691.

Hahn, E. A., Holzner, B., Kemmler, G., Sperner-Unterweger, B., Hudgens, S. A., & Cella, D. (2005). Cross-cultural evaluation of health status using item response theory: FACT-B comparisons between Austrian and U.S. patients with breast cancer. Evaluations & The Health Professions, 28(2), 233–259.

Heil, J., Holl, S., Golatta, M., Rauch, G., Rom, J., Marme, F., et al. (2010). Aesthetic and functional results after breast conserving surgery as correlates of quality of life measured by a German version of the Breast Cancer Treatment Outcome Scale (BCTOS). Breast, 19(6), 470–474.

Jayasekara, H., Rajapaksa, L. C., & Brandberg, Y. (2008). Measuring breast cancer-specific health-related quality of life in South Asia: Psychometric properties of the Sinhala version of the EORTC QLQ-BR23. Quality of Life Research, 17(6), 927–932.

Montazeri, A., Harirchi, I., Vahdani, M., Khaleghi, F., Jarvandi, S., Ebrahimi, M., et al. (2000). The EORTC breast cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-BR23): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Quality of Life Research, 9(2), 177–184.

Pandey, M., Thomas, B. C., Ramdas, K., Eremenco, S., & Nair, M. K. (2002). Quality of life in breast cancer patients: Validation of a FACT-B Malayalam version. Quality of Life Research, 11(2), 87–90.

Parmar, V., Badwe, R. A., Hawaldar, R., Rayabhattanavar, S., Varghese, A., Sharma, R., et al. (2005). Validation of EORTC quality-of-life questionnaire in Indian women with operable breast cancer. National Medical Journal of India, 18(4), 172–177.

Sprangers, M. A., Groenvold, M., Arraras, J. I., Franklin, J., te Velde, A., Muller, M., et al. (1996). The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: First results from a three-country field study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 14(10), 2756–2768.

Yoo, H. J., Ahn, S. H., Eremenco, S., Kim, H., Kim, W. K., Kim, S. B., et al. (2005). Korean translation and validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast (FACT-B) scale version 4. Quality of Life Research, 14(6), 1627–1632.

Yun, Y. H., Bae, S. H., Kang, I. O., Shin, K. H., Lee, R., Kwon, S. I., et al. (2004). Cross-cultural application of the Korean version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Breast-Cancer-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-BR23). Supportive Care in Cancer, 12(6), 441–445.

Alawadhi, S. A., & Ohaeri, J. U. (2010). Validity and reliability of the European Organization for Research and Treatment in Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ): Experience from Kuwait using a sample of women with breast cancer. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 30(5), 390–396.

Awad, M. A., Denic, S., & El Taji, H. (2008). Validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaires for Arabic-speaking populations. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1138, 146–154.

Belmonte Martinez, R., Garin Boronat, O., Segura Badia, M., Sanz Latiesas, J., Marco Navarro, E., & Ferrer Fores, M. (2011). Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Questionnaire for Breast Cancer (FACT-B+4). Spanish version validation. Medicina Clínica (Barc), 137(15), 685–688.

Bernhard, J., Sullivan, M., Hurny, C., Coates, A. S., & Rudenstam, C. M. (2001). Clinical relevance of single item quality of life indicators in cancer clinical trials. British Journal of Cancer, 84(9), 1156–1165.

Carlsson, M., Hamrin, E., & Lindqvist, R. (1999). Psychometric assessment of the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire (LSQ) and a comparison of a randomised sample of Swedish women and those suffering from breast cancer. Quality of Life Research, 8(3), 245–253.

Chie, W. C., Chang, K. J., Huang, C. S., & Kuo, W. H. (2003). Quality of life of breast cancer patients in Taiwan: Validation of the Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23. Psycho-Oncology, 12(7), 729–735.

Coster, S., Poole, K., & Fallowfield, L. J. (2001). The validation of a quality of life scale to assess the impact of arm morbidity in breast cancer patients post-operatively. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 68(3), 273–282.

Fernández-Suárez, H. G., Blum-Grynberg, B., Aguilar-Villalobos, E. J., & Bautista-Rodríguez, H. (2010). Validación de un instrumento para medir calidad de vida en pacientes con cáncer de mama. Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 48(2), 133–138.

Kontodimopoulos, N., Ntinoulis, K., & Niakas, D. (2011). Validity of the Greek EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 for measuring health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer Care (England), 20(3), 354–361.

Ng, R., Lee, C. F., Wong, N. S., Luo, N., Yap, Y. S., Lo, S. K., et al. (2012). Measurement properties of the English and Chinese versions of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) in Asian breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 131(2), 619–625.

Wan, C., Tang, X., Tu, X. M., Feng, C., Messing, S., Meng, Q., et al. (2007). Psychometric properties of the simplified Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-BR53 for measuring quality of life for breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 105(2), 187–193.

Wan, C., Yang, Z., Tang, X., Zou, T., Chen, D., Zhang, D., et al. (2009). Development and validation of the system of quality of life instruments for cancer patients: breast cancer (QLICP-BR). Supportive Care in Cancer, 17(4), 359–366.

Wan, C., Zhang, D., Yang, Z., Tu, X., Tang, W., Feng, C., et al. (2007). Validation of the simplified Chinese version of the FACT-B for measuring quality of life for patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 106(3), 413–418.

Zawisza, K., Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B., Nowak, W., Kulig, J., & Jedrys, J. (2010). Validity and reliability of the quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ C30) and its breast cancer module (EORTC QLQ BR23). Ginekologia Polska, 81(4), 262–267.

Bullinger, M., Power, M. J., Aaronson, N. K., Cella, D. F., & Anderson, R. T. (1996). Creating and evaluating cross-cultural instruments. In B. Spilker (Ed.), Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials (pp. 659–668). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers.

Hui, C., & Triandis, H. C. (1985). Measurement in cross-cultural psychology: A review and comparison of strategies. Cross Cultural Psycology, 16, 131–152.

Costa, L. O., Maher, C. G., & Latimer, J. (2007). Self-report outcome measures for low back pain: Searching for international cross-cultural adaptations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 32(9), 1028–1037.

Chopra, I., & Kamal, K. M. (2012). A systematic review of quality of life instruments in long-term breast cancer survivors. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 14.

Schellingerhout, J. M., Heymans, M. W., Verhagen, A. P., de Vet, H. C., Koes, B. W., & Terwee, C. B. (2011). Measurement properties of translated versions of neck-specific questionnaires: A systematic review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 87.

Okamoto, T., Shimozuma, K., Katsumata, N., Koike, M., Hisashige, A., Tanaka, K., et al. (2003). Measuring quality of life in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review of reliable and valid instruments available in Japan. Breast Cancer, 10(3), 204–213.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira, I.S., da Cunha Menezes Costa, L., Fagundes, F.R.C. et al. Evaluation of cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaires: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 24, 1179–1195 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0840-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0840-3