Abstract

The aim of this paper is to explore how the structural changes that have occurred in the labour market, in terms of employment composition by skill levels, affect wage inequality in three developed countries of Western Europe that are in close geographical proximity but have disparities in their labour market characteristics. More precisely, the analysis compares, from an international perspective, France, Germany—whose labour markets have been characterised in recent years by job polarization and the upgrading of occupations, respectively—and Italy, where neither of the two phenomena can be clearly identified. Using EU-SILC (European Union—Survey on Income and Living Conditions) data, in the first step, RIF-regression (Recentered Influence Function) enables an exploration on the primary factors that are likely to explain the differences in generating personal labour earnings and, in the second step, a decomposition of the change in wage inequality between 2005 and 2013 to evaluate how much of the overall gap is accounted for by the endowments in employees’ individual characteristics (composition effect) rather than the capability of labour markets to transform these characteristics into job opportunities and earnings (wage structure). Regarding France and Germany, the main results highlight how the endowment effect plays a key role in decreasing or, at least, not increasing wage inequality, whereas in Italy the rising inequality may be due to the lower efficiency of the country’s labour market in creating job opportunities, better job-related careers, and higher-salaries for employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background and introduction

Changes occurred over time in the structure of the labour market and in the distribution of wages are the focuses of research interests of many economists (Acemoglu 1999; Autor 2003; Goos et al. 2009a), and a rising body of literature (Aghion et al. 1999; Cornia 2004; Milanovic 2005) has been inspecting the evolution of income inequality and how it plays out in alternative institutional contexts (Alesina and Rodrik 1994; Abel and Deitz 2012; Piketty 2006). Since the 1970s and after a lengthy period of stability (Piketty and Saez 2003), inequality in the United States has significantly grown along the entire income distribution (Juhn et al. 1993; DiNardo et al. 1996), giving rise to what Noah (2013) defines as the Great Divergence. Similar trends also appear in Europe as a whole, but it is necessary to make specific evaluations on each individual country since the general growth of inequality has characterised the European States to different extents, timings, and intensities (Acemoglu 2003). Many forces may be contributing to this trend in income inequality, which is particularly affected by the earnings from work (OECD 2015) and reflects the position of individuals in the labour market, their skills and the opportunities and returns that they receive (Nolan et al. 2014). On these grounds, Sweden, among the traditionally more egalitarian countries (Fritzell et al. 2014), and the United Kingdom, among the most unequal advanced nations (McKnight and Tsang 2014), show the greatest increases in earnings inequality (Acemoglu 2002; Atkinson and Brandolini 2010; Toth 2014). More precisely, as for the United States, by the end of the 1980s, the inequality has decreased in the lower part of the wage distribution (the 50–10 gap has decreased, i.e., the difference between the 50th and the 10th quantile) and simultaneously it has grown in the top end of the wage distribution, widening the gap 90–50 (Autor et al. 2006; Kenworthy and Smeeding 2014). Labour market institutions (Atkinson and Piketty 2007; OECD 2012b), social protection and redistributive systems (Nolan et al. 2014; Castellano et al. 2016), the structure of education systems and policies (Braga et al. 2013; Bol and Van de Werfhorst 2013; Hanushek and Wößmann 2006) inevitably affect the distribution of earnings.

Accordingly, the above-mentioned changes in income inequality may be contextualised in some structural changes that have occurred in the labour market in most developed countries, and among which, job polarization deserves a special attention. It consists of a decrease in the demand for middle-skill workers, with a simultaneous growth in the demand for jobs requiring high and low skills (Autor 2003; Goos and Manning 2007). The first pioneering studies on job polarization, which concern the United States (Autor et al. 2003b) and the United Kingdom (Goos and Manning 2007), proposed, through the classification of jobs according to the average or median earnings (which is a proxy for the level of expertise required to perform the occupation itself), the creation of three distinct groups of workers in high-, middle-, and low-skill, followed by the evaluation of changes over time of employment shares in each category. Considering a time span from 1979 to 2007 in the United States, Autor (2010) traces the period during which the phenomenon began to show itself. Effectively, in the decade of 1989–1999, the empirical evidence confirmed that the distribution of occupations followed the typical behaviour of job polarization, where job growth doubled for the high-skill groups and nearly doubled at the lower ends of the skill distribution. Instead, in the previous decade, the US labour market was mainly characterised by the upgrading of occupations, which favours activities with high qualifications, the only ones that increase the share of employment with respect to those low and medium skilled (Autor 2010). However, Abel and Deitz (2012) demonstrated how the composition of the workforce in the United States has strongly changed during the three decades 1980–2010 and how the entire period has been characterised by insignificant growth of the middle-skill jobs that are lost almost exclusively during recessions and never recover once they fell (Jaimovich and Siu 2012).

Among the economists (Autor et al. 1998; Acemoglu 2002) it is generally accepted the postulate according to which the occurrence of one structure rather than another depends on the current relationship between workers’ skills and the technological progress, and the two theories of task-biased technological change (Autor and Katz 1999; Autor et al. 2003a, b; Acemoglu and Autor 2011; Goos and Manning 2014; Adermon and Gustavsson 2015) and skill-biased technological change (Card and DiNardo 2002; Goldin and Katz 2008) may help explain the driving forces behind job polarization and upgrading of occupations, respectively. At the core of the task-biased technological change there are the tasks required to perform a job, divided into the three categories of routine tasks, which require middle skills to be carried out and the impact of technological replacement is high, non-routine manual tasks, which are less influenced by technology and involve limited skills that are not replaceable by machines because they are not repetitive, and non-routine intellectual tasks, where the technological development is complementary to workers’ skills even though automation cannot replace their creativity and experience. According to this theory, the overall impact of technology may cut down the middle-skilled workers and expanding the remaining two sub-categories. In contrast, based on the skill-biased technological change, benefits from the scientific and technological progress are exclusively reserved for workers with high skills. This advantage can be attributed to their ability to quickly master the new instruments available and, consequently, increasing the productivity of their work. However, benefits obtained are temporary since they are related to a higher rate of learning of high-skilled workers with respect to those less qualified.

Regarding the empirical studies on Europe, the structure of the labour market, in terms of job polarization rather than upgrading of occupations, has been investigated for the United Kingdom (Goos and Manning 2007), Germany (Spitz-Oener 2006; Kampelmann and Rycx 2013), Italy (Olivieri 2012), and, in a perspective closely related to the wage polarization, also for some other countries of the Old Continent (Goos et al. 2009b; Acemoglu and Autor 2011; Nellas and Olivieri 2015). More precisely, by grouping workers of 16 European Union countries in three groups of occupations by the average wage levels, Goos et al. (2009b) argued that job polarization appears to be at least as pronounced in Europe as in the United States and the largest decline of middle wage occupations occurs in France and Austria, while the smallest in Portugal. Despite the choice of the median income (rather than the mean) as the parameter used to classify occupations in the United Kingdom, Goos and Manning (2007) obtained results that are substantially in line with what has been shown for the US market. The change in skill requirements was confirmed by Spitz-Oener (2006), who demonstrated how the labour market of the Western Germany has experienced changes similar to those that have occurred in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Therefore, the central aspect of this work is to understand how the structure of the labour market, in terms of employment composition by skill levels, may affect the changes in wage distribution, focusing on the European labour markets for which these issues have not yet been fully explored. The aim is to explore what structural change in the labour market (i.e., job polarization rather than upgrading of occupations) has played out in France, Germany and Italy during the years 2005–2013 in order to understand the likely causes and their potential relationships with wage inequality and, in this respect, the future developments that the labour market can take. With this object in view, the recentered influence function (RIF) regression allows exploring the main determinants of the wage inequality generating-process and decomposing the changes over time in the inequality of income from dependent work (Firpo et al. 2007; Fortin et al. 2011). This two-stage procedure that generalizes the Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition (Blinder 1973; Oaxaca 1973) has the advantage of being applied to different distributional statistics beyond the mean (e.g., quantiles, variance or Gini coefficient). The overall change in the Gini index of wage distributions is thereby split into the effect of change in the endowment of characteristics and the effect of change in the capability of transforming these characteristics into earnings; further, these two components are decomposed to evaluate the contribution of each covariate to the above mentioned changes in the Gini index.

The paper is structured as follows. By an internationally comparative approach based on EU-SILC data, Sect. 2 shows an explanatory analysis in order to discriminate the national labour markets characterised by job polarization from those where the upgrading of occupations is more marked or also from other structures that cannot be clearly attributable to neither of the two. Section 3 deals with methodological issues to estimate the RIF-regression models and to decompose the total changes in the Gini index over time. Section 4 discusses the meaning of the changes in the wage distribution by subgroups of employees in France, Germany and Italy between 2005 and 2013. Sections 5 and 6 argue, respectively, the main evidence from the RIF-regression of Gini on log-wage and the contribution of each determinant to the overall inequality gap. Concluding remarks and a few considerations for policymakers can be found in Sect. 7.

2 Data source and a preliminary analysis

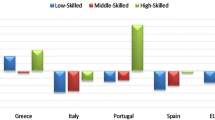

The present Section proposes a comparison between the employment shares for each of the three groups of high-, middle-, and low-skill workers, in 2005 and 2013, in Europe, and explores how these changes have displaced a range of jobs that have traditionally been held by the sphere of middle-skill workers, thereby modifying the structure of employment and income distribution.

Data are from the European Union-Survey on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey, which is currently the largest source for comparable statistics on income, social exclusion and living conditions at the European level. Coordinated by Eurostat, the EU-SILC project assures international comparability by a shared framework of harmonised target variables, common guidelines, classifications, and procedures. The analysis focuses on employees (i.e., anyone who works for a public or private employer and receives compensation in the form of wage, salary, fee, payment by result or in kind), aged 16–64, and irrespective of his/her activity sector, excluding those employed by military occupations. Who is working in a parent’s firm and receives a regular wage is similarly classified as an employee, and in the case of multiple jobs, any worker who allocates the greatest number of hours usually worked in the wage-employment is considered employee. The choice of 2005 and 2013 as the reference years allows one to obtain clues about the social and economic scenarios that were foreshadowed in France, Germany and Italy before and during the global crisis, whose effects continue to be felt, and its role in affecting the structure of labour markets and the patterns of wage inequality as well as their dynamics over time.

The first step is the creation of the three groups of workers according to the skills required to do the specific job and checking how they are distributed across European countries. Unlike to what was seen in some previous works (Autor 2003; Goos and Manning 2007; Goos et al. 2009a), in this paper, following the classification proposed by Eurostat (2010), the average level of education is chosen as a measure of skills required. Although this grouping may be subject to distortion due to the presence of skill mismatched workers (Sicherman 1991; Hartog 2000; Chevalier 2003; OECD 2011), it is of negligible interest with respect to the objectives given the strong correlation between the present average levels of education and skills required to perform the job (Eurostat 2010), and the equally high correlation between the mean education level and the minimum skill requirements (Ashton and Green 1996; OECD 2001). More specifically, jobs are defined according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08), and then rank ordered in line with the mean level of education in the three broad categories of high-, middle-, and low-skill jobs. Eurostat (2010) demonstrated the reliability and accuracy of this grouping by comparing the EU-SILC and US occupational classifications according to which minor differences in rankings exist, which might not be of much importance in the purpose of examining changes in the employment share over time.Footnote 1

Figure 1 shows the percentage changes in employment between 2005 and 2013 for each of the three broad categories of employees by skill levels across 23 European countries. The results allow classifying countries depending on the patterns of the labour market sketched over time in terms of job polarization, upgrading of occupations, or neither of the two. Interestingly, in the group of countries belonging to Central and Northern Europe (i.e., Czech Republic, Hungary, Germany, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) middle-skill occupations has declined as a share of employment, giving breath to jobs for workers at the high end of the skill spectrum and sparing the jobs at the low end. Among these countries, it is worth noting Hungary, whose labour market may be considered as a shining model of employment polarization: low- and high-skill works increased by 23 and 47 %, respectively, whereas the share of middle-skill jobs does not vary significantly. Similarly, the German labour market—which saw a fall of the middle-skill occupations by roughly 40 % between 2005 and 2013, while the low- and high-skill jobs do not show any significant change in the same period (Table 1)—shows a labour market structure ascribable to job polarization.

Austria, France, Portugal, and Sweden are, among all, the countries whose labour markets are mostly characterised by upgrading of occupations. They share the growth of professions demanding high skills and the simultaneous contraction of low- and middle-skill activities. In France, the above-mentioned jobs both decreased by 32 %, and meanwhile the share of high-skill workers increased by 24 %. Finally, as for Cyprus, Estonia, Italy, Poland, and Spain, the percentage changes of the shares of employment between 2005 and 2013 do not enable to say if it prevails a phenomenon rather than the other. In particular, for Italy it does not seem to be possible to define clearly which structure succeeds, because the share of employees has decreased for each of the three groups in contrast to both the job polarization, where the only middle-skill jobs have fallen, and the upgrading of occupations, which comprises a decreasing of the share of employees in low- and middle-skill works with simultaneously growth of the high-skilled.

In order to evaluate how the changes in the labour market are affecting wage inequality, a representative country is selected from each of the three groups described. As shown above, the analysis focuses on France, Germany—whose labour markets are characterised by upgrading of occupations and job polarization, respectively—and Italy, whose structure of the labour market cannot be clearly defined in the time span considered. These empirical dynamics of employment composition in the years 2005–2013 are rigorously in line with what has been argued by Goos et al. (2009b) and Autor (2010), who explored the changes between 1993 and 2006 in the occupations, grouped into the same broad categories of low-, middle-, and high-skills by average wage level, across 16 European countries. Consistently with our results, they show a decrease in both low- and middle-skill jobs in France and Italy, and just in the middle-skill works for Germany.

For each country, the employment shares by skill levels in 2005 and 2013 and their relative changes over time are now discussed. In Germany, the middle-skill activities decreased from 53 % of the total in 2005 to 41 % in 2013. This decline, coupled with the growth in both low-skill (from 13 to 17 %) and high-skill (from 34 to 43 %) activities, drives job polarization in the German labour market.

In France, the proportion of employees in high qualification activities increased from 28 to 42 %, and the simultaneously shrinking shares of employment for low-skill works (from 26 to 21 %) and middle qualifications (from 46 to 37 %) gives evidence of a structure of the labour market characterised by the upgrading of occupations within the designated period of time. By observing the percentage changes in Italy, it is evident a trend similar to France with a proliferation of high-skill jobs (from 23 to 34 %) and a fall of both low-skill (roughly 55 %) and middle-skill activities (by 58 %) that could lead to the same conclusions. However, in order to conclude with the presence of the upgrading of occupations in Italy, the number of employed in high-skill jobs would be significantly increased between 2005 and 2013. In reality, Fig. 1 shows that the share of employees has contracted for each of the three categories of workers, something that does not allow one to reach a clear conclusion about the structure of the Italian labour market.

3 Methodology: recentered influence function (RIF) regression

A cross-country comparison of wage inequality presupposes knowledge of the main determinants of the wage-generating and the wage-inequality-generating processes in each country. In this work, the recentered influence function regression (Firpo et al. 2007, 2009; Fortin et al. 2011) of an inequality measure (Gini index) on log-wages has been tested. The RIF-regression replaces the log-wage as dependent variable with the recentered influence function of Gini coefficient v(F), and estimates directly the impact of explanatory variables on the Gini index, taken on as the distributional statistic of interest, which gives an overall measure of inequality based on the whole wage distribution because it considers the relative position of every employee and not just those at the extremes (i.e., ratio 90/50, or 50/10). Once the RIF function has been estimated for each country, the overall gap in the Gini coefficient between 2005 and 2013 is disentangled into the wage structure and the composition effect, and then these components are computed for each covariate to identify those factors that are quantitatively more significant to make inequality differentials over time.

Many methods, such as Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition (Blinder 1973; Oaxaca 1973), can explore the role of each covariate on the changes in wage inequality. Indeed, as widely known, the Oaxaca–Blinder procedure allows decomposing changes in mean wages into the wage structure and the composition effects, and once obtained these two components, it would be possible to analyse the contribution each covariate provides. However, the Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition has two main limitations because the estimation of the wage structure and composition effects can be misleading if the linear model is unspecified (Barsky et al. 2002), and the contribution of each covariate to the wage structure is highly sensitive to the choice of the base group (Oaxaca and Ransom 1999; Gardeazabal and Ugidos 2004). Another aspect to consider is that the Oaxaca–Blinder method enables to apply the decomposition only to the mean (Firpo et al. 2007).

The RIF methodology is well suited to the objective of the paper that is to analyse the changes over time of wage inequality because it allows one to obtain the decomposition of the Gini index (or also other distributional statistics, such as median and variance). Other procedures overcome these disadvantages—e.g., the Juhn et al. (1991, 1993) method and the quantile based decomposition by Machado and Mata (2005)—but their main shortcoming is the inability to trace the contribution provided by each covariate to the composition effect, whenever they are used to compute the decomposition to various distributional statistics (Firpo et al. 2007). To overcome this further specific limitation, the RIF-regression has been chosen.

Suppose that a sample of individuals divided into two groups is observed, 0 and 1. N1 and N0 are the number of units in each group and the individuals are by the index i = 1,…, N. Y 1i is the wage of worker i of the group 1, instead, Y 0i represents the wage that would be paid in group 0. An important aspect is that one can observe Y 1i or Y 01 , but not both, because individual i is only observed in one of two groups. Consequently, the observed wage Y i is defined as:

where \(T_{i} = 1\) when worker i is observed in group 1. \(T_{i} = 0\), instead, if is observed in group 0.

In general, \(Y_{i}\) can be written without imposing specific functional form considering the wage determination function of observed components \(X_{i}\) and some unobserved components εi:

Let v be the generic distributional statistic to study and IF the influence function, introduced as a measure of robustness of v to the presence of outlier (Hampel 1974). The RIF-regression is:

The above expression can be written as:

where \(\beta^{v}\) represents the marginal effect of X on v. The v-overall wage gap between the period 0 and 1 can be measured as follows:

that can be decomposed into:

In this way, the overall wage gap over time is decomposed into two components: wage structure (\(\Delta_{s}^{v} )\) and composition effect \((\Delta_{x}^{v} )\). The first term corresponds to the effect on v of a change from \(g_{1} ( \cdot , \cdot )\) to \(g_{0} ( \cdot , \cdot )\) keeping the distribution of \(\left. {({\text{X}},{{\varepsilon }})} \right|T = 1\) constant. Conversely, the composition effect keeps the wage structure \(g_{0} ( \cdot , \cdot )\) constant and measures the effect of changes from \(\left. {({\text{X}},{{\varepsilon }})} \right|T = 1\) to \(\left. {({\text{X}},{{\varepsilon }})} \right|T = 0\). However, the key term for decomposing the total wage gap is the counterfactual distributional statistics \(v_{c}\) (Firpo et al. 2007)Footnote 2 that represents the distributional statistic that would have prevailed if workers observed in the group 1 have the wage structure of period 0.

To identify the parameters of counterfactual distributions it is important to define three weighing functions (DiNardo et al. 1996; Firpo et al. 2007):

\(\omega_{1} \left( T \right)\) and \(\omega_{0} \left( T \right)\) transform features of the marginal distribution of Y into features of the conditional distribution of Y 1 given T = 1, and of Y 0 given T = 0. The last function, \(\omega_{c} \left( {T,X} \right)\), is the function that allows one to estimate the counterfactual distribution of Y 0 given T = 1.

4 Changes in wage inequality by subgroups of employees

Changes occurred in wage inequality, expressed by the Gini index, over the period 2005–2013, are evaluated through the RIF-regression that includes a preliminary step where the Gini on log-wage is regressed on a set of individual characteristics, human capital and job background variables that potentially drive the observed inequality. The employees’ income, which is composed of cash, near cash and non-cash wages or salaries, is specified in the gross form, e.g., the total earnings from work received during the reference period, before any deductions for tax or social insurance contribution.Footnote 3 Specifying wage in the gross form enables one to compare more countries regardless of the complexity of their alternative tax rules. Under a different approach (e.g., using the net income), the comparison between France, Germany and Italy would not be suitable because of their different fiscal regimes (e.g., the French fiscal system is typically household-based, whereas in Italy, it is more individual-based).

As regards personal characteristics, gender is a dummy variable with value 1 if the employee is male and 0 otherwise. Couple is a derived variable based on the marital status, which is the conjugal status of each worker in relation to the marriage laws of the country, and consensual union to consider if they live in the same household. In such a way, couple has three modalities, e.g., never married, currently married sharing or not the same house (also legal spouse or registered partner or “de facto” partner), and others who also experienced marriage in the past (e.g., separated, divorced, and widowed). General health is 1 for employees who do not suffer from any chronic illness or condition (long-standing, that is permanent and requiring a long period of supervision, observation or care, while temporary problems are not of interest) and 0 otherwise. Then, formal education at different levels and non-formal enterprise-based training and experience acquired through work are certainly the most relevant and measurable settings for human capital development. In this light, education attainment refers to the highest level of formal education (ISCED-97)Footnote 4 a person has successfully completed, using three categories of low (ISCED-97: 0;1;2), medium (3;4), and high (5) education. Experience refers to the number of years since starting the first regular job that a person has spent at work.Footnote 5 As regards job characteristics, the variables economic status and type of contract are dummies with value 1 if the employee is full-time (0 if part-time) and with a permanent contract (0 if temporary), respectively. Finally, the occupation type is composed of ten dummies each of them captures specific professional status (ISCO classification) scaled according to skill levels. The following tables (Tables 2, 3, 4) show descriptive statistics separately for France, Germany, and Italy by year and any of the aforementioned factors. The Gini indexes and their percentage variations over time (2005–2013) are proposed by each subgroup of population.

A first important aspect to consider is the way in which the shares of employees are changed by type of occupation between 2005 and 2013 as well as the evolution of wage inequality within each sub-category of workers. In the context of the progressive weakening of the middle-skill employees in Germany (Table 1), it is worth underlining that it is largely due to the shrinkage of clerks, whose share has decreased from 43 percent in 2005–24 percent in 2013. Regardless of their substantial narrowing over time, clerks have not affected by any significant change in wage inequality, mainly in Germany where the decrease in Gini index, in percentage terms, was a little more than 3 (Table 3). A similar sharp decreasing trend in the share of clerks has also been experienced in France (from 34 to 20 %) and Italy (from 40 to 30 %) as well, thus contributing greatly to the dropping of middle-skill employees in both countries (Tables 2 and 4), albeit with an opposite tendency of wage inequality (−7.86 % of Gini index in France and +10.70 in Italy). Machine operators stand for the category of low-skill employees that fell more drastically in France (from 12 in 2005 to 7 % in 2013) and running much the same way as what has occurred in Italy (from 14 to 9 %). Moreover, wage inequality within the subgroup of senior officials has widened in each of the three countries, especially for Germany (by roughly 27 %). The largest decrease in wage inequality has taken place within the German agricultural skilled (−23.23 %) employees and French managers of small enterprises (−35.17 %), whereas the opposite occurred in Italy. In fact, in Italy, Gini indexes have increased significantly for both occupations (+26.95 and +35.04 % for agricultural skilled employees and managers, respectively) as well as for nearly all kinds of job positions, except for professionals (−12.93 %), while teaching professionals are the high-skill employees whose inequality has increased the most (+31.38 %). Among the middle-skill jobs, the Italian managers of small enterprises with an increase of 35 % of Gini index are those with the largest growth in wage inequality. Finally, within low-skill wage-earners, the highest inequality strengthening involved the skilled agricultural for whom the Gini index has risen from 0.2705 in 2005 to 0.3434 in 2013 and elementary occupations of roughly 25 %.

As for the formal education attainment, in both Germany and France, wage inequality has declined for the better educated wage-earners, whereas has mostly increased for employees who have just attained the primary education in all three countries (+35.90, +20.55, +14.60 % for Italy, Germany and France, respectively). However, in Germany, the very low educated employees are just 2 % of the total and this incidence is consistently lower than what has been observed for Italy and France. Unlike to what happens in Germany and France, the Gini index has increased for all Italian employees, regardless of their education attainment (even for the high-educated), except for the residual subgroup of illiterates (−33.11 %). An additional feature that is common to the three countries is the increasing wage inequality irrespective of the economic status (full time vs. part time) and type of contract (permanent vs. temporary), with the only exception of German and French fixed-term employees for whom the Gini index has respectively decreased (−4.83 %) and remained fairly stable.

5 Determinants of wage inequality: main empirical evidence

As illustrated above, in the first step, RIF-regressions of Gini on (log of) gross individual wage are estimated for France, Germany, and Italy, separately for the years 2005 and 2013, through the maximum likelihood method, which enables a consideration of the personal analytic weights (Table 5). The choice to measure inequality of personal labour earnings is motivated by the interest in explaining the determinants of inequality in the individual capacity to earn income, regardless of how resources are pooled, how individuals share them within their household (Castellano et al. 2016) and how individuals participate in the decision processes (Beninger and Laisney 2002). The adoption of a similar approach of labour supply behaviour—an approach that is consistently supported by many authors (Samuelson 1956; Becker 1991)—results from this paper’s general aim to investigate earnings inequalities in light of individuals’ capacity to succeed in the labour market and enables one to overcome the potential problems that result from an exaggerated emphasis on the household as the basic unit of decision rather than on individual wellbeing. Additionally, labour-market earnings are the main income source for most individuals and, therefore, are crucial drivers of household income inequality (Frémeaux and Picketty 2014). Excluding the self-employed can be misleading because it may hide the duality of the labour market and the differences in the inequality levels according to whether they are considered or not (Parker 2004). Nevertheless, the adverse effects of income under-reporting (say, the practice of declaring lower earnings than were actually received, usually for income tax purposes), that concerns more self-employed than employees for institutional reasons (Rees and Shah 1986; Bettio and Verashchagina 2009; Hurst et al. 2014), and the great diversity between employees and self-employed in personal characteristics and labour market settings, and, not least, the high heterogeneity of self-employment (Parker 2004; Castellano and Punzo 2013), lead us to the choice of restricting the analysis to the employees. Those issues are beyond the scope of this paper, which clearly implies that the results are only directly valid in the restricted context of employees. However, this contribution may form the basis for future works in the attempt to extend the analysis to a more complex context where the main differences between employees and the self-employed could be accounted for.

The results show the crucial role of gender, education and work experience in determining wage inequality and draw attention to the economic status, type of contracts and type of job held as driving forces of inequalities. Reading the regression coefficients for gender, both German (just for 2005) and Italian women contribute (on average) more than their male colleagues to wage inequality. However, it seems that, on average, in Italy the influence of females on widening earnings inequality (compared to males) is higher than in Germany, even after controlling for part-time (vs. full-time), temporary (vs. permanent) and occupation type. Indeed, the gender coefficient becomes insignificant for Germany in 2013 despite of the rising tendency of female participation in the labour market and their growing wage inequality (+4.76, Table 3). As the women’s entry in the labour market has differently increased over the period 2005–2013 in the three States (roughly three percent points for Germany and Italy, and less than two percent points for France; Tables 2, 3, 4), and the Gini index, which is generally higher for females, has also followed various trends (e.g., it has decreased in France and strongly risen in Italy), the wage gap with males could affect the overall income distribution in different ways. In brief, the gender dimension remains one of the driving forces of wage inequality (Brandolini et al. 2010) in Germany and Italy, but not in France. In particular, for German and Italian females, wage inequality has increased of 4.76 and 20.86 % of Gini points, respectively, whereas for French women it has even declined (−3.53 %) and this partly justifies the insignificance of gender coefficient for France in the RIF-regression models (Table 5). In France, the higher benefits for maternity leave and child allowances (even for unmarried mothers) should be more effective and should encourage the quality and productivity of work of the larger share of female employees (above all when compared to Italy), improving their income-generating opportunities (Castellano et al. 2016). Indeed, in France, family-oriented policies, which are designed to prevent dismissals (e.g., chômage partiel), provide generous allowance systems, especially for large and/or low-income households and working mothers. Conversely, although Italy has an official policy of equal treatment and opportunities, the policy is not very actively enforced. The shortage of services for children and the elderly would make it difficult for women to reconcile work and family life and to pursue career advancement. This reality conforms to the “Mediterranean model of the welfare state”, which relies extensively on women’s unpaid work as providers of care services (European Commission 2010). Similarly, attempts to introduce a universal income support programme modelled on the French Revenu Minim d’Insertion have never succeeded (Ballerino et al. 2014). Then, it is worth noting that to be married increases earnings inequality in both Germany and France, but not in Italy, where the contribution to wage inequality seems to be practically the same for all employees despite of their conjugal status, except for 2013 when it results that to have been married in the past (now separated, divorced or widowed) has risen inequality. In France, no significant differences exists between workers who are in a legal separation or divorce (or even those who are widowed) and those who are married, whereas in Germany being never married has given breath to wage inequality just for 2005 (Table 5). Indeed, German unmarried employees are more unequal even though their wage inequality has dropped by 15.72 % between 2005 and 2013 (Table 3), an element that can help explain the reverse of the sign of beta coefficient in the RIF-regression (Table 5).

Broadly, the evidence shows how better education and more experience in the labour market can serve as tools to reduce wage inequality. Differences in the levels of formal education surely affect personal earnings (Castellano et al. 2016), and a large support to earnings inequality seems to come from the lowest educated employees (Table 5). In Germany, the positive beta coefficients for low and middle-educated people would imply an increasing contribution to wage inequality compared to the high-educated, whereas in Italy the middle-educated employees run in the reverse direction. Probably, in Italy, the low share of employees with tertiary education (less than one-fifth of the total), who also suffer from largest within-groups inequality (Gini index is higher than 30 % on both the years), involves increasing earnings disparities. Although high-educated employees—whose share has slightly been increasing over the last decades, but it is still quite low to the EU averages (Ballarino et al. 2014)—who are more skilled, would be more oriented towards building better job-related careers, and thus better average salaries, their relative little incidence inevitably strengthens the gap with their low-educated counterpart. Conversely, in Germany, the high share of post-secondary educated employees, who enjoy a lower within-group inequality than their worse educated colleagues (Table 3), plays a crucial role in the process of decreasing wage inequality. In fact, Germany has currently a leading position in Europe with one of the best rates of post-secondary education (Corneo et al. 2014), which in great measure is first- or second-stage tertiary education, while another strength lies precisely in the structure of its education system. The highly stratified and more vocational oriented system, where occupational status and earnings may be more closely related to individual education attainment, may provide more specific skills required by the labour market (Allmendinger 1989; Kerckhoff 2001; Shavit and Muller 2000), and this appears to act in reducing wage inequality. In this regard, Scherer (2005) found a stronger effect of vocation-specific education on the school-to-work transition in Germany compared to Italy, suggesting that vocational oriented systems may smooth the transition to work for everyone, principally for those who are better educated and thus with more specific qualifications (Andersen and van de Werfhorst 2010). In particular, it is worth noting that the German “dual system” of apprenticeship, which pools together theoretical education with the practical learning on the workplace, may target workers towards more specific skills that can directly be exploited in working activities with unavoidable effects on their earnings (Castellano and Punzo 2015). These results partly agree with those of other studies investigating how education is related to income distribution and inequality. On these grounds, De Gregorio and Lee (2002) empirically proved that a higher and more equally distributed education plays a significant role in making income distribution equal. Countries with higher educational attainment would show more equal income distribution, and countries with greater inequality in education would experience lower investment rates, slower economic growth, and more persistent income inequalities (Castellano and Punzo 2015). Frémeaux and Piketty (2014) argued how in France the growing education attainment over time has improved income inequality across cohorts as a direct effect—also confirmed by results from RIF-regressions that give evidence of the pejorative contribution of less educated employees to wage inequality—of the greater chances of high-educated people to get a better paid job. Moreover, just as for formal education, the results demonstrate how the experience in the labour market, which increases human capital accumulation throughout the life cycle, also act in lowering wage inequality. The positive sign of experience-squared confirms the concavity of earnings-experience relationship according to which earnings tend to advance rapidly for the early years in the labour market, flatten in later years, and decline slightly thereafter, with their related effects on inequality.

Large wage differentials are also associated with the status in employment and, above all, with the different typologies of occupation. More specifically, since part-time workers receive, on average, lower salaries with earnings trajectories usually less steep than their full-time counterparts, wage inequality becomes more relevant as soon as the incidence of part-timers increases. Indeed, a high share of part-timers affects the overall income distribution by increasing the weight of lower wages on the left side of the same distribution. This effect is particularly large in Germany where the incidence of part-time employees, which is also increasing over time (from 23.98 to 27.67 % in 2005 and 2013, respectively) as well as their levels of inequality (+19.68 %), is around twice that of Italy (from 10.30 to 15.41 % with an increase of wage inequality by 9.36 %). Really, in Germany, the rise of more precarious jobs became significant from 2003 onwards (Corneo et al. 2014) with the renovations of active labour market policy carried out through the Hartz-reforms, which foresees, among other things, the deregulation of temporary employment and the creation of agencies to place people in works even if they differ from own profession, and thus the broadening of minor occupations by means of social security exemption (Eichhorst and Marx 2011; Dlugosz et al. 2014). Indeed, German temporary workers, with a Gini index close to one-half, are largely more unequal than their French (and Italian) colleagues, even though a slight decrease in wage inequality has occurred between 2005 and 2013 (−4.83 %). However, in Italy, the share of temporary employees is more or less the same in both years, but their levels of inequality have dramatically increased (+29.14 %), also as a potential result of deregulation undertaken since 1997 (e.g., Treu Package, Biagi Reform) that have sought to increase flexibility to new entries in the labour market with the effect of increasing the amount of fixed-term workers, primarily young people and women, with worse salaries and a volatile employment attachment. In France, the high minimum wage, which has continued to increase from 1980 to 2010, has helped decrease income inequality, while the deregulation has led to the creation of a dual market with an increasing of part-time works and short-term contracts. In brief, although small numbers of working hours and fixed-terms contracts worsen wage inequality, differences in the levels of earnings inequality between employment contracts must be necessarily explained in light of the different institutional landscapes and labour market trends, in terms of flexibility and insecurity of employment conditions, across countries (McCall 2000).

Moving on the occupation types scaled according to skill levels, one of the most striking findings is that all professions contribute to improve earnings inequality compared to the more elementary jobs (Table 5). Reading the regression coefficients for occupation, it is worth noting that, in general, the contribution of the different type of job in lowering wage inequality appears to be stronger (on average) in Germany. Just for France, some categories of the higher rungs of social ladder (e.g., in 2013, senior officials, managers, and professionals) becomes insignificant in the process of earnings inequality decreasing. Broadly, in Germany, a great deal of wage inequality concerns elementary occupations, service workers, and some other categories of the lower rungs, likely due to the effect of Hartz reforms that contribute to increasing the labour demand of low-skilled workers (Corneo et al. 2014), whereas in Italy the opposite happens: high-skilled workers—e.g., senior officials, professionals, and managers—are characterised by more severe inequalities. These results are substantially in line with Wolff and Zacharias (2013), who demonstrated that the growth of income inequality between 1989 and 2000 was mostly due to the intensification of inequality among occupations. This large amount of wage inequality suggests that the huge income gap between some occupational groups (e.g., the capitalist class and everyone else) is one of the main forces behind increasing inequality because of the stronger instability of unskilled workers and clerks compared to individuals in intermediate or managerial positions (Frémeaux and Piketty 2014; Castellano et al. 2016).

6 Decomposing wage inequality over time

In the second step, the RIF-regression allows us to apply the breakdown of the overall difference of Gini coefficients over time. Once the RIF-regressions of Gini on log-wage have been estimated for each country, differentials in Gini coefficients between 2005 and 2013 have been decomposed into the composition effect, wage structure, and interaction effect. The latter is a residual part of the decomposition that captures the leverage produced by both effects happening simultaneously. Standard errors of components are computed according to the method detailed in Jann (2008) (see also Firpo et al. 2007, 2009, 2011).

As illustrated, France, Germany, and Italy have been characterised by different patterns in the change of employment composition over time that may affect the dynamics of wage inequality to a different extent. Based on this analysis on EU-SILC data, the overall Gini index has slightly declined for Germany between 2005 and 2013, whereas the magnitude of the fall has been more pronounced for France, sufficiently in line with the current literature (Corneo et al. 2014; Frémeaux and Piketty 2014). In addition, Dustmann et al. (2009) and Fuchs-Schundeln et al. (2010) argued that, in Germany, inequality, which was rather stable during the 1980s, increased after reunification for the entire wage distribution, accelerating in the years 2000–2005, and becoming roughly constant thereafter. Similarly, Becker (2006) found that German employees without a full-time job suffered from wage stagnation and that the overall inequality increased, although the “within group” wage inequality did not change significantly between 1998 and 2003. In France, the level of inequality among full-time wage-earners has decreased during the 1980s and 1990s and has been stable ever since, albeit with important differences along the entire wage distribution (Piketty 2003; Landais 2009; Godechot 2012). Conversely, for Italy, the analysis shows a substantial rise in the overall Gini coefficient of the wage distribution over the time span of interest, consistently with the literature that classifies Italy as an unequal country (Ballarino et al. 2014).

At this point, it could be interesting to analyse how each component (composition effect vs. wage structure) contributes to the overall gap in Gini index over time (Table 6).

First, for all three countries, RIF-regression decomposition highlights a significant contribution of both composition (endowment) and wage structure (return) effects. For Germany and France, a great deal of the total gap is attributable to the composition effect (94.38 and 76.32 %, respectively) and thus most of the total inequality differential depends on the changes on employees’ individual characteristics happened over time. Instead, in Italy, the wage structure, which represents structural changes that have occurred in the country’s labour market and in its capacity of transforming inputs into job opportunities and earnings, plays a leading role in the increase of wage inequality over time (93.08 %). In other words, the amount of changes between 2005 and 2013 in the structure of the Italian labour market has a larger incidence than that due to employees’ individual characteristics.

The greater importance of endowments or characteristics effects concerns those countries, as France and Germany, where the evolution of the structure of the labour market (upgrading of occupations and job polarization, respectively) appears to be more explicit and clearly defined. In fact, in these two countries, the endowments in workers’ characteristics and potentialities have contributed more effectively to decrease or, at least, not to increase wage inequality over time. By contrary, in Italy, where the configuration of employment by skill levels appears more ambiguous, the increasing differential in wage inequality is more attributable to the possibilities that the labour market offers at any given time as well as to its changes during the eight years of interest. As they say, in Italy, the disadvantage in terms of endowments (28.94 %) is partly rewarded for the return effect (93.08 % for Italy vs. 32.35 and 46.17 for Germany and France, respectively), confirming how the lack of a well-defined structure of the labour market may have significant consequences on the inequality within the country. However, the large contribution of the wage structure component in increasing wage inequality over time may be partly explained by the lower efficiency of the Italian labour market to create better job opportunities and careers, and thus better salaries for employees.

Second, in order to identify those factors that are quantitatively more significant to make differential over time, the components by RIF-regression decomposition have been computed by each explanatory variable (Tables 7, 8, and 9). In general, job background variables (e.g., type of contract, economic status, and occupation) have a greater weight on the composition effect for Germany and France compared to what happens in Italy where the same variables have a larger effect on the wage structure. In short, being unmarried and working full-time with a permanent contract contribute to decreasing the Gini coefficient in the composition effect for both France and Germany. Then, it is worth noting the significant role in lowering wage inequality of high-skill jobs (compared to the low- and middle-skill) in the wage structure, whereas the low-skill in Germany and the middle-skill jobs in France increasing wage inequality in the composition effect. As discussed in Sect. 5, these results have to be necessarily read in light of country’s deregulation measures. For example, there is a consensus that in Germany, although the effects of the Hartz legislation are not completely clear, they have substantially increased the so-called atypical employment, such as marginal part-time and temporary jobs, which have risen from 10 to 15 % in the last 15 years (Corneo et al. 2014), and have contributed to widen gaps in the wage distribution because they receive lower salaries and are more affected by unemployment risk. Just for Germany, similar thoughts can be traced as regards the educational attainment: low-educated employees contribute in increasing wage inequality in the composition effect, emphasising the importance of the highly stratified system in creating education attainment more closely related to skills required by the labour market. In this regard, Kreidl et al. (2014) underline that industrialisation and advanced processes of technological change require that stratification place individuals into positions in the social structure based on skills.

As regards Italy, for both composition and wage structure effects, high-skilled wage-earners with a permanent contract have a much smaller effect in the increasing wage inequality, as well as the high-educated employees in the wage structure (Table 8). Instead, in the composition effect, medium educated employees contribute less than the high-educated in increasing inequality, whereas this role is more incisive for the low-educated.

Finally, the RIF-regression decomposition confirms the insignificance of gender in changing wage inequality in France for both components; conversely, to be female increases wage inequality differently in Germany and Italy, reinforcing, respectively, the wage structure and the composition effect. As they say, the generally more effective family-oriented policies in France and the different division of roles within couples may facilitate women to reconcile work and family life, providing them higher opportunities to reach leadership position and better average salaries (Jenson and Sineau 2001; Lanquetin et al. 2000).

7 Concluding remarks

This paper has been designed to investigate the changes in wage inequality occurred between 2005 and 2013 in France, Germany, and Italy in light of some structural changes that have involved their labour markets. One of the main elements of this work’s novelty is its linking the research of primary forces of wage inequality, in a comparative perspective, to the decomposition of its overall change over time by any factor that drives it, taking into account how the changes in employment composition have modified the structure of labour markets in terms of job polarization (Germany) rather than upgrading of occupations (France) or neither of the two (Italy).

In general, our results confirm the existence of significant differences in the extent to which each sub-category of employees affects the overall wage inequality across countries and draw a clear contraposition between France and Germany, on the one side, and Italy, on the other one. More specifically, wage inequality decreased between 2005 and 2013 in both Germany (slight decreasing) and France—where well-defined structures of polarization into low- and high-skill jobs and upgrading into high-skill employment are, respectively, sketched—and increased substantially in Italy, which is proving to be one of the most unequal countries in the OECD area (Ballarino et al. 2014). These results are quite consistent with Goos et al. (2009a), who showed that even a potential relationship between wage inequality and the structure of employment would not necessarily prove causality, while are partly consistent with those obtained by Goos and Manning (2007) for the United Kingdom in the years 1976–1995, who argued that a fraction of wage inequality can be explained by job polarization, mainly at the top of the wage distribution. Therefore, changes in wage inequality over time and across countries could be thought of as coming from the other varying institutional, socio-economic, and political arrangements in different States. For example, historically Italy has spent very little on active labour-market policies (0.5 % of GDP), and its spending is approximately half that of France (Ballarino et al. 2014), which is not lacking in challenges in improving legal frameworks that provide equal employment opportunities by gender and the better alignment between lifelong learning opportunities and the labour market’s needs. The lack of a legal minimum wage and the low level of contract decentralisation undoubtedly affect Italy’s ability to prevent increases in income inequality, while decreased trust in politics and the state’s weakness do not facilitate the implementation of redistributive policies that would effectively reduce all types of inequality and social distances (Ballarino et al. 2014; Castellano et al. 2016).

Also based on the differences in the extent to which the primary common factors (i.e., gender, education, and job background characteristics) affect wage inequality in the three countries allow us to separate France and Germany—where more cutting-edge employment and social policies are drawn (Frémeaux and Piketty 2014; Corneo et al. 2014)—from Italy, where the weaker redistributive strategies in the context of a greater political instability make the situation worse (Ballarino et al. 2014; Castellano et al. 2016). For example, while in Italy the gender dimension remains one of the driving forces of inequality because policies of equal treatment are not much actively enforced, French women benefit of reconciliation measures that encourage their participation in the labour market and their opportunity to build better job-related careers and salaries. Similarly, in Germany, the high share of better educated employees, consistently above the EU averages, and the stratified and vocational oriented education system, which is more able to provide workers with specific skills required by the labour market, play a crucial role in lowering wage inequality. However, the association between wage differentials and the status in employment (e.g., wage inequality seems to increase as part-timers or temporary jobs increases) rather than the type of occupation (e.g., all professions improve the total wage inequality compared to the elementary and unskilled jobs) stresses how the national employment protections, which aim to decrease the rigidities of the labour market (e.g., the Hartz reforms in Germany, or the Treu Package and Biagi Reform in Italy), continue to have strong and controversial effects on the overall wage inequality.

The contraposition between France and Germany with Italy becomes even clearer at the end of the paper where it is argued how the changes on employees’ individual characteristics have greater role in lowering (or, at least, not increasing) wage inequality in France and Germany; instead, in Italy, where the configuration of employment by skill levels is still ambiguous, inequality rising is potentially due to the structural changes happened in the country’s labour market and to its lower ability in creating better job opportunities and higher earnings for employees. The more differentiated picture by each significant factor of wage inequality confirms how job-related characteristics have a greater weight on the composition effect for Germany and France compared to what happens in Italy for which they have a larger effect on the wage structure.

In brief, the overall wage inequality is largely explained by the differences in characteristics among the most vulnerable groups of employees and by the existence of high levels of within-group heterogeneity and thus within-job pay dispersion. From a policy perspective, knowing the different degree of wage inequality among employees will help identify the weaknesses of each category of workers and understand whether and in which side implement any adjustment or how reorganise investments and readdress the available resources, bearing in mind that the social profitability of redistributive policies is highly sensitive to countries’ labour market structures. In particular, policies lowering wage inequality would be focused, on the one side, on ensuring all individuals, mainly young and women, are able to enter the labour market and provide more job opportunities for those with low-skill levels; on the other side, policies would be addressed in boosting wage progressions and upgrading skills for low-paid employees that can increase their potential earnings and facilitate their social mobility.

Our results are sensitive to the period during which the wage inequality and the occupational structures are measured (2005–2013), beyond the inequality measure used (Gini coefficient), and are directly valid in the context of employees; thus, they cannot be extended to a general perspective of income inequality. However, they form the basis to extend the analysis to a wider-ranging comparison across European countries in which differences between employees and the self-employed could be explored and the impact of each dimension on individuals’ labour income and income inequality could be investigated along the entire conditional earnings distribution to determine workers’ heterogeneity depending on their relative position across the same distribution.

Notes

In brief, following Eurostat (2010), high-skill jobs include: (1) Legislators, senior officials, and managers; (2) Corporate managers; (3) Physical, mathematical and engineering science professionals; (4) Life science and health professionals; (5) Teaching professionals; (6) Other professionals (including business, legal, social science); (7) Physical and engineering science associate professionals; (8) Life science and health associate professionals; (9) Teaching associate professionals. Middle-skill jobs comprise: (1) Managers of small enterprises; (2) Other associate professionals; (3) Office clerks; (4) Customer service clerks; (5) Personal and protective service workers; (6) Models, salespersons, and demonstrators; (7) Building and extraction trades workers; (8) Metal, machinery and related trades workers; (9) Precision, handicraft and printing workers. Finally, low-skill jobs embrace: (1) Skilled agricultural and fishery workers; (2) Other craft and related trades workers (including food processing, textile); 3) Stationary plant and machine operators; (4) Machine operators and assemblers; (5) Drivers and mobile plant operators; 6) Sales and services elementary occupations; (7) Agricultural, fishery and related labourers; (8) Labourers in mining, construction, manufacturing and transport.

The conditions that allow one to identify the parameters of the counterfactual distribution are ignorability, which states that the distribution of the unobserved explanatory variables in the wage determination is the same across groups 1 and 0, and overlapping support, which requires that there be an overlap in observable characteristics across groups in the sense that there is no covariate such that it is only observed among individuals in group 1.

For Italy and exclusively for the year 2005, the gross wage was approximated by using the gross monthly income, considering the months during which the employee has experienced a paid employment.

In the EU-SILC framework, formal education is measured along a simplified version of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97), which has six main categories of education attainment: pre-primary (0) and primary (1) education, lower (2) and upper (3) secondary education, post-secondary non-tertiary (4) education, and first- and second-stage (5) tertiary education.

For the year 2013 the variable experience was not available, and only in that case, it was approximated as the difference between the current age and the school-leaving age.

References

Abel, J.R., Deitz, R.: Job polarization and rising inequality in the nation and the New York-northern New Jersey region. Curr. Issues Econ. Financ., Federal Reserve Bank of New York 18 (2012)

Acemoglu, D.: Changes in unemployment and wage inequality: an alternative theory and some evidence. Am. Econ. Rev. 89, 1259–1278 (1999)

Acemoglu, D.: Technical change, inequality, and the labor market. J. Econ. Lit. 40, 7–72 (2002)

Acemoglu, D.: Cross-country inequality trends. Econ. J. 113, 121–149 (2003)

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D.: Skills, tasks and technologies: implications for employment and earnings. In: Ashenfelter, O., Card, D. (eds.) Handbook of Labor Economics 4B, pp. 1043–1171 (2011)

Adermon, A., Gustavsson, M.: Job polarization and task-biased technological change: evidence from Sweden, 1975–2005. Scand. J. Econ. 117(3), 878–917 (2015)

Aghion, P., Caroli, E., García-Peñalosa, C.: Inequality and economic growth: the perspective of the new growth theories. J. Econ. Lit. 37, 1615–1660 (1999)

Alesina, A., Rodrik, D.: Distributive politics and economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 109, 465–490 (1994)

Allmendinger, J.: Educational systems and labour market outcomes. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 5, 231–250 (1989)

Andersen, R., van de Werfhorst, H.G.: Education and occupational status in 14 countries: the role of educational institutions and labour market coordination. Br. J. Sociol. 61(2), 336–355 (2010)

Ashton, D.N., Green, F.: Education, Training and the Global Economy. Edward Elgar, London (1996)

Atkinson, A.B., Brandolini, A.: On analyzing the world distribution of income. World Bank Econ. Rev. World Bank Group 24(1), 1–37 (2010)

Atkinson, A.B., Piketty, T.: Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century: A Contrast Between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2007)

Autor, D.: Outsourcing at will: the contribution of unjust dismissal doctrine to the growth of employment outsourcing. J. Labor Econ. 21(1), 1–42 (2003)

Autor, D.: The Polarization of Job Market Opportunities in the US. Center for American Progress, Washington (2010)

Autor, D., Katz, L.: Changes in the wage structure and earnings inequality. In: Handbook of Labor Economics, 3A (1999)

Autor, D., Katz, L., Krueger, A.B.: Computing inequality: have computers changed the labor market? Q. J. Econ. 113, 1169–1213 (1998)

Autor, D., Lawrence, H., Katz, F., Kearney, M.S.: The polarization of the U.S. labor market. Am. Econ. Rev. 96, 189–194 (2006)

Autor, D.H., Levy, F., Murnane, R.: Computer-Based Technological Change and Skill. Low-Wage America. Russell Sage Foundation, New York (2003a)

Autor, D., Levy, F., Murnane, R.: The skill content of recent technological change: an empirical exploration. Q. J. Econ. 118, 1279–1333 (2003b)

Ballarino, G., Braga, M., Bratti, M., Checchi, D., Filippin, A., Fiorio, C., Leonardi, M., Meschi, E., Scervini, F.: Italy: how labour market policies can foster earnings inequality. In: Nolan, S., Checchi, M., McKnight, T., van de Werfhorst, G. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Barsky, R., Bound, J., Charles, K., Lupton, J.: Accounting for the Black-White Wealth Gap: a nonparametric approach. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 97(459), 663–673 (2002)

Becker, G.S.: A Treatise on the Family. University Press, Harvard (1991)

Becker, I.: Effektive Bruttostundenlohne in Deutschland. Eine Verteilungsanalyse unter Aspekten der Leistungsgerechtigkeit und besonderer Berucksichtigung des Niedriglohnsegments, Arbeitspapier n. 2 des Projekts, Soziale Gerechtigkeit, J.W. Goethe Universitat Frankfurt a Main (2006)

Beninger, D., Laisney, F.: Comparison between unitary and collective models of household labor supply with taxation. ZEW Discussion Paper no: 02-65 (2002)

Bettio, F., Verashchagina, A.: Fiscal System and Female Employment in Europe. Fondazione G. Brodolini, Italia (2009)

Blinder, A.: Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J. Hum. Resour. 8, 436–455 (1973)

Bol, T., Van de Werfhorst, H.G.: Educational systems and the trade-off between labor market allocation and equality of educational opportunity. Comp. Educ. Rev. 57, 285–308 (2013)

Braga, M., Checchi, D., Meschi, E.: Educational policies in a long-run perspective. In: Beck, T., Fuchs-Schündeln, N., Gürkaynak, R., Ichino, A., Lane, P. (eds.) Economic Policy. Center for Economic Studies of the University of Munich, Oxford (2013)

Brandolini, A., Rosolia, A., Torrini, R.: The distribution of employees’ labour earnings in the EU: data, concepts and first results. Eurostat Working Paper, European Union (2010)

Card, D., DiNardo, J.E.: Skill-biased technological change and rising wage inequality: some problems and puzzles. J. Labor Econ. 20(4), 733–783 (2002)

Castellano, R., Punzo, G.: Patterns of earnings differentials across three conservative European welfare regimes with alternative education systems. J. Appl. Stat. 43, 140–168 (2015)

Castellano, R., Manna, R., Punzo, G.: Income inequality between overlapping and stratification: a longitudinal analysis of personal earnings in France and Italy. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 30(5), 567–590 (2016)

Castellano, R., Punzo, G.: The role of family background in the heterogeneity of self-employment in some transition countries. Trans. Stud. Rev. 20(1), 79–88 (2013)

Chevalier, A.: Measuring overeducation. Economica 70, 509–531 (2003)

Corneo, G., Zmerli, S., Pollak, R.: Germany: rising inequality and the transformation of rhine capitalism. In: Nolan, B., Salverda, W., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, I.G., van de Werfhorst, H.G. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries, pp. 271–298. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Cornia, G.A.: Inequality, Growth and Poverty in an Era of Liberalisation and Globalisation. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2004)

De Gregorio, J., Lee, J.W.: Education and income inequality: new evidence from cross-country data. Rev. Income Wealth 48(3), 395–416 (2002)

DiNardo, J., Fortin, N., Lemieux, T.: Labor Market Institutions and the Distribution of Wages, 1973-1993: a semi-parametric approach. Econometrica 64, 1001–1045 (1996)

Dlugosz, S., Stephan, G., Wilke, R.: Fixing the leak: unemployment Incidence before and after a major reform of unemployment benefits in Germany. German Econ. Rev. 15(3), 329–352 (2014)

Dustmann, C., Ludsteck, J., Schonberg, U.: Revisiting the German wage structure. Q. J. Econ. 142(2), 843–881 (2009)

Eichhorst, W., Marx, P.: Reforming German Labour Market Institutions: a dual path to flexibility. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 21(1), 73–87 (2011)

European Commission: Tackling the Gender Pay Gap in the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg (2010)

Eurostat: Educational Intensity of Employment and Polarization in Europe and the US. Eurostat Methodologies and Working Paper (2010)

Firpo, S., Fortin, N., Lemieux, T.: Decomposing wage distributions using recentered influence function regressions. University of British Columbia (2007)

Firpo, S., Fortin, N., Lemieux, T.: Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica 77(3), 953–973 (2009)

Fortin, N., Lemieux, T., Firpo, S.: Decomposition methods in economics. In: Handbook of Labor Economics (2011)

Fremeaux, N., Piketty, T.: France: how taxation how increase inequality. In: Nolan, S., Checchi, M., McKnight, T., van de Werfhorst, G. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Fritzell, J., Hertzman, JB., Bäckman, O., Borg, I., Ferrarini, T., Nelson, K.: Sweden: increasing income inequalities and changing social relations, Changing inequalities and societal impacts in rich countries: thirty countries’ experiences. Oxford University Press: Oxford (2014)

Fuchs-Schundeln, N., Krueger, D., Sommer, M.: Inequality trends for Germany in the last two decades: a Tale of two countries. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 13(1), 103–132 (2010)

Gardeazabal, J., Ugidos, A.: More on identification in detailed wage decompositions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 86(4), 1034–1036 (2004)

Godechot, O.: Is finance responsible for the rise in wage inequality in France? Socio-econ. Rev. 10(2), 1–24 (2012)

Goldin, C., Katz, L.F.: The race between education and technology: the evolution of U.S. educational wage differentials, 1890 to 2005. National Bureau of Economic Research (2008)

Goos, M., Manning, A.: Lousy and lovely jobs: the rising polarization of work in Britain. Rev. Econ. Stat. 89, 118–133 (2007)

Goos, M., Manning, A., Salomons, A.: Job polarization in Europe. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 58–63 (2009a)

Goos, M., Manning, A., Salomons, A.: The polarization of the European labor market. Am. Econ. Rev. Papers Proc. 99(2), 118–133 (2009b)

Goos, M., Manning, A., Salomons, A.: Explaining job polarization: routine-biased technological change and offshoring. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 2509–2526 (2014)

Hampel, F.R.: The influence curve and its role in robust estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 69, 383–393 (1974)

Hanushek, E.A., Wössmann, L.: Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries. Econ. J. 11, 63–76 (2006)

Hartog, J.: Over-education and earnings: where are we, where should we go? Econ. Educ. Rev. 19, 131–147 (2000)

Hurst, E., Li, G., Pugsley, B.: Are household surveys like tax forms? Evidence from income underreporting of the self-employed. Rev. Econ. Stat. 96, 19–33 (2014)

Jaimovich, N., Siu, H.E.: The trend is the cycle: job polarization and jobless recoveries. National Bureau of Economic Research 18334 (2012)

Jann, B.: Oaxaca: Stata module to compute the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Statistical Software Components, Boston College Department of Economics (2008)

Jenson, J., Sineau, M.: France: reconciling republican equality with “Freedom of Choice”. In: Jenson, J., Sineau M. (eds.), Who Cares? Women’s Work Childcare, and Welfare Redesign, pp. 88–117 (2001)

Juhn, C., Murphy, K., Pierce, B.: Wage inequality and the rise in returns to skill. J. Polit. Econ. 101, 410–442 (1993)

Juhn, C., Murphy, K.M., Pierce, B.: Accounting for the slowdown in black-white wage convergence. In: Kosters, M.H. (ed.) Workers and Their Wages: Changing Patterns in the United States, pp. 107–143. AEI Press, Washington (1991)

Kampelmann, S., Rycx, F.: The dynamics of task-biased technological change: the case of occupations. Brussels Econ. Rev. 56(2), 113–142 (2013)

Kenworthy, L., Smeeding, T.: The United States: high and rapidly-rising inequality. In: Nolan, S., Checchi, M., McKnight, T., van de Werfhorst, G. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Kerckhoff, C.A.: Education and social stratification processes in comparative perspective. Sociol. Educ. (Extra Issue), 3–18 (2001)

Kreidl, M., Ganzeboom, H.B.G., Treiman, D.J.: How did occupational returns to education change over time? California Center for Population Research on-line Working Paper Series (2014)

Landais, C.: Top incomes in France (1998-2006): booming inequalities? PSE working paper (2009)

Lanquetin, M.T., Laufer, J., LeTablier, M.T.: From equality to reconciliation in France. In: Hantrais, I. (ed.) Gendered Policies in Europe: Reconciling Employment and Family Life, pp. 68–88. MacMillan, London (2000)

Machado, J.A.F., Mata, J.: Counterfactual decomposition of changes in wage distributions using quantile regression. J. Appl. Econ. 20, 445–465 (2005)

McCall, L.: Explaining levels of within-group wage inequality in U.S. Labor market. Demography 37(4), 415–430 (2000)

McKnight, A., Tsang, T.: Divided we fall? The wider consequences of high and unrelenting inequality in the UK. In: Nolan, S., Checchi, M., McKnight, T., van de Werfhorst, G. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Milanovic, B.: Worlds Apart: Measuring International and Global Inequality. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2005)

Nellas, V., Olivieri, E.: Polarization trends and labour market institutions. Working Papers (2015)

Noah, T.: The Great Divergence: America’s Growing Inequality Crisis and what We Can Do About It. Bloomsbury, New York (2013)

Nolan, B., Salverda, W., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, I.G., van de Werfhorst, G.: Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Oaxaca, R.: Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int. Econ. Rev. 14(3), 693–709 (1973)

Oaxaca, R., Ransom, M.R.: Identification in detailed wage decompositions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 81(1), 154–157 (1999)

OECD: Competencies for the Knowledge Economy. OECD, Paris (2001)

OECD: Building Knowledge, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard. OECD: Paris (2011)

OECD: Inequality in labour income—what are its drivers and how can it be reduced? OECD Economics Department Policy Notes 8, Paris (2012a)

OECD: OECD Employment Outlook. Paris (2012b)

OECD: In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. OECD: Paris (2015)

Olivieri, E.: Il Cambiamento delle Opportunità Lavorative. Questioni di Economia e Finanza, Banca D’Italia (2012)

Parker, S.C.: The Economics of Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2004)

Piketty, T.: Income inequality in France, 1901–1998. J. Polit. Econ. 111(5), 1004–1042 (2003)

Piketty, T.: The evolution of top incomes: a historical and international perspective. Am. Econ. Rev. 96(2), 200–205 (2006)

Piketty, T., Saez, E.: Income inequality in the United States 1913–1998. Q. J. Econ. 118, 1–39 (2003)

Rees, H., Shah, A.: An empirical analysis of self-employment in the U.K. J. Appl. Econ. 1, 95–108 (1986)

Samuelson, P.A.: Social indifference curves. Q. J. Econ. 70, 1–22 (1956)

Scherer, S.: Patterns of labour market entry—long wait or career instability? An empirical comparison of Italy, Great Britain and West Germany. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 21, 427–440 (2005)

Shavit, Y., Müller, W.: Vocational secondary education, Where diversion and where safety net? Eur. Soc. 2(1), 29–50 (2000)

Sicherman, N.: Overeducation in the labor market. J. Labor Econ. 9, 101–122 (1991)

Spitz-Oener, A.: Technical change, job tasks and rising educational demands: looking outside the Wage structure. J. Labor Econ. 24, 235–270 (2006)