Abstract

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 led many American Indian tribes to adopt formal constitutional texts to govern life on reservations. Over the following decade, dozens of tribes ratified their constitutions in hopes that they would start a new age of tribal self-governance. Given the opportunities for constitutional design subject to constrains, we develop a theory of constitutional choice on reservations. Tribal constitutions varied substantially in content and structure. We evaluate the constitutional choices tribes made regarding four areas: membership requirements, direct democracy, restrictions placed on officials, and protection of private property. Our theory yields several hypotheses that we test against data on 117 tribal constitutions, most of which were ratified in the aftermath of the IRA. The results provide evidence for the validity of our hypotheses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Foundational to the entire public choice enterprise is the idea that one must study political phenomena and institutions as an outcome of maximizing behavior. Building on the classic work of Buchanan & Tullock (1965) and its extensions by Sass (1991, 1992), we develop a theory to study the constitutional choice of American Indian tribes following the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. Tribal constitutions varied substantially in content and structure. Some tribes included strict membership requirements while others did not. Some tribes embraced direct democracy; others embraced representative government. Some placed restrictions on elected officials, such as term limits, but others did not feel the need to do so. Some placed laws on the protection of private properties of reservation residents while others did not. Our theory yields several hypotheses for which we find evidence using data on 117 tribal constitutions.

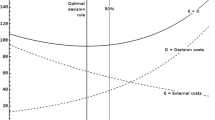

Like Buchanan & Tullock (1965), we treat constitutional rules as the result of a trade-off between decision-making and external costs. Decision-making costs refer to the value of resources sacrificed to achieve consensus over a piece of legislation, public policy, or any other government action. These costs are increasing in the minimum number of people that must agree before passing a motion. External costs, on the other hand, are the value of resources the state employs to either reallocate wealth or prevent the reallocation of wealth between constituents. Unlike decision-making costs, external costs are inversely related to the minimum number of votes needed to approve a motion. Following Sass (1991), we expand the meaning of external costs to include the value of resources employed in mitigating agency problems. Unlike other external costs, agency costs are incurred only in representative democracies and are a decreasing function of the ratio of elected representatives over voters.Footnote 1

We explore this framework’s implications over several characteristics of tribal constitutions: membership requirements, the choice between direct democracy and representative government, the imposition of constraints on elected officials (especially eligibility requirements and term limits), and the emphasis on protecting the property rights of reservation residents.

Of particular interest are our framework’s implications for membership requirements. For many American Indian tribes, membership requirements took the form of blood quantums.Footnote 2 A tribe would restrict the ability to join their ranks to individuals who could prove to have “tribal blood” above some minimum value. However, not all tribes set the same quantum. Some tribes, like the Southern Ute Tribe in Colorado, might require that members “be of 1/2 or more degree of Ute Indian blood.” Others, like the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska, might adopt an implicit blood quantum of zero. Our framework accounts for this variation by characterizing blood quantums as a mechanism to restrict access to commonly owned resources capable of exhaustion. Thus, the constitutions of American Indian groups with a larger value of reservation land owned in common by the tribe should also include more stringent blood quantums.Footnote 3

We test the empirical implications of this framework against data on the constitutions of American Indian tribes.Footnote 4 We analyzed 117 constitutional documents, a majority of which were drafted and ratified in the aftermath of the IRA. We then extracted data on several variables related to constitutional choice. We merged the resulting data set with information on demographic, economic, and social characteristics of the American Indian tribes in our sample.

The results of our empirical tests are largely consistent with our hypotheses. Tribes with a larger share of reservation land owned in common systematically adopted stricter blood quantums to regulate membership. We find that larger tribes and tribes with a greater share of the land under tribal management are significantly less likely to adopt direct democracy. A larger value of tribal land share further predicts higher minimum age requirements for tribal officials and shorter term lengths. Moreover, our results suggest that recall elections and shorter term limits functioned as substitute institutional solutions to agency problems between tribal voters and their representatives. Finally, we find that the per capita value of private land on the reservation is (positively) predictive of the probability that a constitution will include a “takings clause.”

Our analysis and results contribute to the positive constitutional analysis literature.Footnote 5 Our approach is most similar to the one employed by Sass in his study of the constitutions of condominiums (Sass, 1992) and those of municipal governments of small towns in Connecticut (Sass, 1991).Footnote 6 In the spirit of these works, some of our predictions focus on the determinants of voting rules and constraints on elected representatives in tribal constitutions including the choice between direct and representative democracy, the inclusion of restrictions on takings by the tribal governments, and the choice of term length and age requirements of representatives.

We also contribute, although indirectly, to the literature emphasizing the importance of tribal political institutions to understand the poor economic performance of so many reservation residents over the twentieth century. American Indians living on reservations have the lowest per capita income in the United States. According to (Leonard et al., 2020, 1), “[i]n 2015, average household income on reservations was 68% below the U.S. average.”

American Indian tribes have a special legal status recognized by the federal government since the country’s founding and reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in a series of decisions, from Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (30 U.S. [5 Pet.] 1, 17 [1831]) and Worcester v. Georgia (31 U.S. [6 Pet.] 515 [1832]) to, most recently, United States v. Cooley (2021). According to Supreme Court precedent, American Indian tribes exist as “distinct, independent political communities” within the United States and enjoy limited rights to self-determination and self-governance. In the exercise of these rights, American Indians may adopt the system of government of their choosing.

Scholars of American Indian development have looked at these political institutions as a potential cause for such poor economic performance (Cornell & Kalt, 1995, 2000; Anderson & Parker, 2009; Cookson, 2010).Footnote 7 Most notably, Akee et al., (2015) argue that tribes that adopted constitutions outlining a parliamentary system of government have experienced significantly higher growth rates in income per capita and other measures of economic performance relative to tribes that opted for a presidential system. Consistent with this result, Anderson (2016) finds evidence that written constitutions are beneficial to economic performance, with Indian tribes that adopted these documents generally experiencing higher income per capita than the rest.

One problem with attempts to measure the effect of political institutions—and constitutions in particular—on tribal economic performance is that these are not distributed randomly across groups.Footnote 8 To a large extent, tribes drafted their own constitutions freely. If some tribe-specific characteristic affected both its constitutional choice and the ability to generate economic output, studies that treat political institutions as exogenous will tend to produce biased results (Sass, 1991). For this reason, understanding the determinants of American Indian constitutional choice can better allow us to identify the independent effect of constitutional characteristics on tribal economic performance and other outcomes of interest.

To characterize the constitutions of American Indian groups as a choice variable is not to say that these groups knowingly chose a path of social and economic stagnation; in fact, the opposite is the case. Our approach suggests that tribes selected the best political institutions available to them, given their economic circumstances and the broader institutional context at the time. Hence, the results of our investigation should be interpreted as giving further validity to approaches that emphasize factors exogenous to reservation politics (Anderson, 2016; Alston, Crepelle, and Murtazashvili 2021). These include consequential historical episodes, like the forced relocation of many American Indian groups away from their ancestral lands and the disruption of sources of economic well-being (Leonard et al., 2020; Carlos et al., 2022; Becker, 2022), as well as the continued interference with tribal life by federal and state agencies (McChesney, 1990; Anderson & Parker, 2009).

2 A brief american indian constitutional history

The first case of a written Native American constitution was the “Great Law of Peace” of the Iroquois Confederacy, dating to the first half of the sixteenth century. However, unwritten constitutions had existed in North America for much longer. Indeed, the Iroquois’ “Great Law” merely transcribed the oral traditions that had regulated the political life of these people for several centuries (Wilkins, 2009, 14). To the extent that they showed any degree of social complexity, every one of the over 600 tribes that inhabited North America at the arrival of the Europeans had a system of government characterized by specific rules. These pre-Colombian Native American constitutions varied substantially. Some groups were organized in small, independent, and highly democratic units, like the Paiutes in Utah and Nevada. Others formed federations in which constituent groups were largely independent in the administration of internal affairs, such as the Iroquois in the Northeast. A third category of tribes was theocracies ruled by a priestly class, like the Pueblos in the Southwest.Footnote 9

Contact with European colonists started a process of institutional change. Traditional forms of government persisted while incorporating elements of European political thought and practice. This institutional blending was in part a response to the changing economic circumstances of the Indian people and the exposure to the colonists’ culture, but partly also the result of the colonial governments’ explicit efforts to mold the political institutions of the indigenous peoples living within their colonies (Wilkins, 2007, 134).

These hybrid constitutions were still largely informal. The first formal constitutional moment among Native American nations started in the early nineteenth century—just a few years after the ratification of the American constitution—and lasted until the start of the Civil War. During this period, some of the largest and best politically organized Indian groups drafted their first written constitutions, including the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seneca nations (Wilkins, 2009). More tribes adopted written constitutions in the decades following the Civil War. For the first time, this process encompassed tribes from the Southwest and the Plains, whose territories had come under the jurisdiction of the United States following the Mexican American War. By and large, these constitutions were the product of internal deliberation by the members and leadership of each tribe. Like those of Spain, France, England, and Mexico before it, the American government influenced this process both directly and indirectly.Footnote 10 However, the initiative was mainly in the hands of the tribes (Clow, 1987).

While tribal self-governance was seriously curtailed by the Dawes Act of 1887, things changed with the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934.Footnote 11 The purpose of this legislation was to put an end to decades of attempts by the federal government to assimilate the Indians into the American public and restore a significant degree of self-determination and self-governance to the tribes (Haas, 1947, 1). Tribes were now entrusted with electing their own governments and selecting the laws by which they were to live (Kelly, 1975, 293).

Moreover, the IRA established the Indian governments’ right to administer and regulate access to tribal assets, particularly land (Haas, 1947, 2). The IRA constituted a 180-degree turn from four decades of federal Indian policy going back to the Dawes Act of 1887.Footnote 12 According to the Dawes Act, tribal lands were to be divided into 160 acres and then allotted to Indian households. For twenty-five years after gaining possession, allottees could use their land as they pleased, except for selling it without the approval of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Any tribal land that had not been so allocated (known as “surplus land”) was made available to non-Indians for allotment and, in the meantime, fell under BIA control. With the passage of the IRA, the federal government abandoned its allotment policy.

While all Indian land already allotted was to remain in the hands of the allottees, the IRA returned authority over surplus lands to the tribes. Moreover, the BIA promoted efforts by the tribes to gain back control of allotted lands (Crepelle, 2019, 438). For instance, allottees lost the right to sell to anyone but the tribal government, regardless of how long they had occupied their plots. Non-Indian beneficiaries of the Dawes Act were similarly prevented from leaving their lots to their heirs (Kelly, 1975, 297).

To benefit from the IRA, the federal government demanded that tribes ratify written constitutions and bylaws formally outlining, among other items, their membership requirements, a system of government, the legislative process, their electoral procedures, and land policy (Wilkins, 2007, 118–119). Within just a few years after the IRA, 93 tribes voted in favor of the IRA and adopted their new constitutions (Anderson, 2016, 379).Footnote 13 With all its emphasis on tribal self-governance, the IRA gave the BIA significant influence over the drafting of tribal constitutions.Footnote 14

The BIA provided tribes with a model constitution to inspire the drafting process (Akee et al., 2015, 847).Footnote 15 The influence of the BIA is clear from a comparison between the texts of tribal constitutions. Virtually all of them shared the same formal structure (starting with a list of constitutional articles followed by a set of bylaws) and similar in content. Even the order of the articles was often the same, starting with a brief preamble, followed by an article outlining the tribe’s jurisdiction, and then by one specifying the tribe’s membership requirements. Tribal constitutions acknowledged that the federal government (in the person of the Secretary of the Interior) maintained ultimate authority over the approval and future changes to these documents via the amendment process. Moreover, the BIA remained involved in the everyday internal affairs of these groups (Haas, 1947, 9).

The experiment in tribal self-governance inaugurated by the IRA was short-lived. In 1953, 19 years later, Congress approved a resolution outlining the so-called termination policy. According to the termination policy, over the subsequent decades, the federal government was to end all programs that gave special treatment to American Indians and their tribes were to lose their status as federally recognized sovereign entities.Footnote 16 The termination policy went even further by encouraging Indians living on reservations to relocate to the city, often by coercive means. Another element of the termination policy that undermined Indian sovereignty was the passage of Public Law 280, which took partial control of the judiciary away from Indian governments and gave it to state courts.Footnote 17

The end of termination in the 1960s, which coincided with the rise of the Civil Rights movement, brought about a new era of Indian self-governance and a new period of political change on the reservation. Tribes that did not yet have a constitution adopted one, and the rest began amending them to respond to new challenges.Footnote 18 Even as tribes enjoyed a greater degree of self-determination in the post-termination period, there have been instances of federal action that limited the ability of American Indian groups to set their own rules. Most importantly, in 1973, Congress passed the Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA), which extended the protections of the fourteenth amendment to tribal citizens against reservation governments.

Presently, American Indian tribes enjoy levels of self-determination comparable to those of the states, though this status quo is conditional on Congress’ will. The political, social, and economic life on the reservation is, to a significant degree, governed by tribal constitutions.

3 Constitutional choice on the american indian reservation

Constitutions exist to outline the rules governing social interactions that are too costly to be organized via private means (Buchanan & Tullock, 1965). However, there are several constitutional arrangements under which collective action plausibly outperforms its private alternatives. We follow a long tradition of positive economic analysis in assuming that, as tribal members come together to draft their constitution, they will select those arrangements that maximize the net per capita wealth of the group.Footnote 19 Since tribes’ circumstances varied (e.g., in their membership size, the value and characteristics of the assets held in common, and their cultural traits), we expect their choice of constitutional arrangements to vary with them. Our analysis focuses on only a subset of the attributes of tribal constitutions. Specifically, we investigate the choice of membership requirements, degree of direct democratic participation, constraints on elected officials, and protection of private property.

3.1 Membership requirements

Managing common resources is an essential prerogative of governments. When resources are held in common, as in the case of tribal lands in Native American reservations, tribes run the risk of having the rents generated by these resources depleted (Cheung, 1970; Libecap and Johnson, 1980). One solution to this problem is to limit access to the tribal commons through strict membership requirements.Footnote 20 However, strict membership requirements come at a cost. For one, they must be enforced: The tribal government must maintain lists of existing members and check the eligibility of prospective ones. Most importantly, however, strict requirements limit the potential size of the tribe. In so doing, they also increase the per capita cost of providing public goods.

As it sets its membership requirements, the tribe must solve the trade-off between larger per capita costs of public good provision and larger per capita commons-generated rents. American Indian tribes’ choice for evaluating the eligibility of prospective members fell on blood quantums.Footnote 21 To obtain the political, legal, and economic rights associated with membership in a specific tribe, one would have had to prove that one’s blood exceeded some minimum quantity of that tribe’s blood. For example, if a tribe set the quantum at one-fourth, eligible prospective members would have had to have at least one grandparent who was a full-blooded member. In drafting its constitution, the tribe could manipulate the blood quantum to restrict the pool of eligible candidates (higher blood quantum) or increase it (a lower blood quantum). According to the reasoning above, tribes with more valuable assets held in common should adopt more stringent membership requirements. Since land was the primary asset held in common by American Indian groups, we expect blood quantums to be increasing in the value of reservation land under tribal control.

3.2 Direct democracy

American Indian tribes are by and large democratic organizations. They can choose between direct democracy, according to which each member is directly involved in the legislative process, and indirect democracy, where members elect representatives to advance their interests in the legislature.Footnote 22 Direct forms of political participation have the advantage of eliminating agency problems, and thus all costs incurred in monitoring representatives. On the other hand, direct democracies suffer from large decision-making costs (Buchanan & Tullock, 1965).Footnote 23 As decision-making costs increase with the size of the polity, the use of traditional institutions by tribes based on members’ direct participation in the legislative process should be inversely related to the size of their population.

Direct democracies suffer from a second problem. Participation of the citizenry in the legislative process would require them to sacrifice other plausibly more productive uses of their time. The alternative would be for the members of the tribe to participate directly, but without investing much in the acquisition of information necessary to produce good tribal policies. As in the case of decision-making costs, this problem becomes only more acute as the size of the population increases, as each voter’s informational investment contributes less to the ultimate policy choice. One way to minimize the cost of collecting information and reduce the voter information problem is to “hire” political middlemen specializing in collecting and processing political information–i.e., professional politicians representing their constituents. Thus, we expect the degree of involvement of the tribal government in the business of the reservation to have an inverse relationship with the prevalence of direct democracy.

3.3 Constraints on elected officials

Indirect democracy might well economize on decision-making costs and mitigate informational free riding; at the same time, it introduces challenges of its own. Representatives might act against the interests of their constituents, due to costly monitoring and the presence of asymmetric information (Barzel & Sass, 1990). In drafting the constitutions, constituents will then want to include provisions to constrain elected officials. One such provision would be to subject the representatives to frequent evaluations of their performance—for example, shorter terms in office (Stigler, 1976).

There are costs to reducing term lengths. A shorter-term length means more frequent elections and thus higher per capita election-related expenses. In addition, voters must now take time to evaluate incumbents and challengers more often and politicians must allocate more of their time to campaigning and fundraising, time that could otherwise be spent legislating. Given the existence of this trade-off, we expect term lengths to be shorter the greater the potential for malfeasance by elected officials. An incumbent’s ability to act against the interest of the public depends in large part on how informed the public is about the incumbent’s voting record. An American Indian voter’s incentive to acquire such information will tend to fall with the size of the tribe’s population. Thus, larger tribes will prefer shorter term lengths.

Limiting terms length is not the only way to mitigate agency problems in representative democracies. Some constitutions might include other checks on politicians, such as the ability of voters to recall their representatives or minimum age requirements for elected offices.

Age requirements on political offices date back to at least 180 BC during the Roman Republic with the introduction of the Lex Villia Annalis which required, among other things, Consuls to be 42 years of age (Evans & Kleijwegt, 1992). The Crow tribe of Indians in Montana requires the executive chief to be at least 30 years old and the legislative branch members to be at least 25 years old. The chief of the executive generally faces greater incentives to act against the interests of voters than members of the legislature. Hence, we should expect the age requirement to be higher for the chief of the executive than for legislators. When the age requirement for the chief of the executive branch (if there is one) is specified in tribal constitutions, this is generally what we observe. For instance, the Muscogee Creek Nation of Oklahoma requires tribal councilmen to be at least 18, while the president must be at least 30.Footnote 24

Minimum age requirements for elected office mitigate agency problems via two channels. First, older individuals are less likely to establish firm ownership of their political offices for long periods, reducing the chance of political entrenchment and indirectly limiting incumbent advantage. In cases where fear of abuses of power is most acute, requiring older citizens to occupy important offices prevents the consolidation of powers in the hands of someone who might be reluctant to give it back.Footnote 25 Second, age requirements will change the pool and eligible members. The older the age requirement to hold an office, the greater the chance is that candidates establish a good and durable reputation.Footnote 26 In other words, age requirements might effectively screen out uncooperative members who are likely to breach their implicit contract with voters.

Lastly, the number of representatives in the legislature will impact the costs and benefits of acting in ways not consistent with voters’ interests. As we explained, representatives are “information specialists” on political markets. A greater number of representatives will reduce the incentive of politicians to act opportunistically as their influence on the final decisions is smaller. On the other hand, a larger legislature will increase the informational problem faced by the representatives, who will be tempted to free ride on their peers.Footnote 27 We should therefore expect the tribal council to be bigger when the benefits from using tribal assets for personal gains increase. The effect, however, is not as straightforward once we consider the existence of multiple branches of government or that increasing the size of the legislature may encourage political opportunism by the executive branch.Footnote 28 American Indian tribes, however, rarely adopted a presidential system before the 1970s.

3.4 Protection of private property

By the introduction of the IRA, a significant share of reservation land had been allotted to private individuals, including some non-Indians. As they drafted their constitutions, Indians living on the reservation might have worried that the newly established tribal governments would take action to regain possession of the allotted lands or otherwise violate their ownership rights.Footnote 29 Landowners have an incentive to insert protections for private property rights in the tribal constitution, including the right to pass one’s land to one’s heirs.Footnote 30 Indeed, the larger the value of the private land, the stronger the incentive to do so. On the other hand, non-owners living on the reservation have the opposite incentive. However, since the benefit to each reservation resident of transferring private land to the tribe is smaller than the loss to the original owner, the logic of concentrated costs and dispersed benefits suggests that landowners would have been more likely to prevail. Thus, we expect that restrictions on the tribal governments’ power to violate private property over land will be more prevalent among tribes with a higher per capita value of private land.

4 Data

For this study, we collected information about 117 constitutions from 1900 to 2013.Footnote 31 Of these, 88 were enacted between 1934 and 1970, 70 of which were ratified between the passing of the IRA and the end of the era of tribal self-governance in federal Indian policy. Figure 1 shows the chronological distribution of the year of ratification of the documents in our sample. Since most of the modern American Indian constitutions were drafted and enacted during this period, we focus our analysis on constitutional texts from the immediate aftermath of the IRA. We do so to mitigate the effect of time-varying factors (including learning) that could have influenced constitutional design.Footnote 32

We gathered this information from publicly available online sources, most notably the Library of Congress’ “Native American Constitutions and Legal Materials” collection.Footnote 33 78 out of the 115 constitutions in our final sample came from this source, as well as 67 out of the 70-constitutions-sub sample that were enacted from 1934 to 1950. We also used a few constitutions made available by “The Memory Hole 2” on archives.orgFootnote 34 as well as a few constitutions transcribed in Fay et al., (1967; 1968). Finally, for a few constitutions, we consulted the official websites of the relevant tribes.

We read and analyzed each document, coded a number of variables based on its content, including but not limited to variables relative to the presence of a blood quantum,Footnote 35 the presence of a takings clause, the size of the tribal council, whether or not the separation of powers was stipulated, the age requirements to be eligible to the tribal council, the ability to recall politicians, and the length of terms on the tribal council.

We selected our dependent variables with an eye on their variation across constitutions. Hypotheses about constitutional features, however interesting, cannot be tested adequately in the absence of variation across constitutions. For instance, in our sample, only two documents from the 1934–1950 period explicitly mention the principle of separation of powers. Although the separation of powers is often associated with constraints on the executive, which might mitigate agency problems in tribal politics, there is simply not enough variation to formally identify this effect using our data. We therefore focused on developing explanations and performing tests related to the most salient differences between tribal constitutions.

In addition to our analogic analysis, we used “tesseract” package in R to perform a “text-as-data” style analysis and extract more information from tribal constitutional documents.Footnote 36 After removing the punctuation and capital letters, we “stemmed” keywords of interest (Gentzkow et al., 2019) and measured their frequency. More specifically, we measured (a) mentions of culture or tradition in the constitutions, (b) mentions of inheritance, and (c) mentions of allotment.

We combined the above information with that on an array of control variables, including: Tribal land value share; the per capita value of individual land; ethnic mixing; the share of members living on reservation; tribal population size; share of adult members of the tribe; share of reservation residents who speak English and that of those wear Western-style clothing; the status of the tribe under the IRA; tribal land in 1934 (%); and allotted Land in 1934 (%). We rely on four main sources for these data.

Demographic variables like “Population” and “Living on reservation” (the portion of Indians residing within the jurisdiction of the tribe in which they were enrolled) are taken from Statistical Supplement to the Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year 1940.Footnote 37

We rely on the annual report of the commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1926 (Burke, 1926) for the following variables.Footnote 38 “Mixing” is defined as the proportion of the population which is not “full blood” Indian. “Adults” refers to the portion of a tribe’s population that is of age. “Land value per capita” is the total dollar value of the land under a tribe’s jurisdiction. “Tribal land value share” is the dollar value of the fraction of reservation land managed directly by the tribe.Footnote 39 “Individual land value” is the dollar value of reservation land that was either allotted or held as fee simple. Data from the latter three variables are from a 1935 report by the United States National Resources Committee (1935).

Finally, our cultural variables are from the 1917 Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. These include measures of the “integration” of tribal members in American society, such as the percentage of reservation residents wearing Western-style clothing instead of traditional American Indian clothing and the share of those who could speak English.

We have one final note on our sample of tribal constitutions. We follow Cornell & Kalt (2000), Anderson & Parker (2008), and Akee et al., (2015) in excluding smaller tribes from our analysis and focus instead on tribes with a population greater than 700 inhabitants in 1940, yielding a total of 87 constitutional documents, new or amended constitutions.Footnote 40

5 Empirical tests: the constitutions of american indian tribes

5.1 Blood quantums

Our empirical framework suggests a positive relationship between the value of land held in common by a tribe and the stringency of the membership requirements to the same tribe. Recall that, traditionally, American Indian groups have relied on ethnic and genealogical standards for membership eligibility. This practice is so widespread among American Indian tribes that, since the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968, the federal government recognizes the rights of these groups to discriminate on a racial basis in matters of membership and political participation (Wilkins, 2007, 155).

Such racial considerations were common to tribal constitutions from the immediate aftermath of the IRA. For instance, Article II of the constitution of the Quechan Tribe of the Fort Yuma reservation in California:

Intermarried Indians or descendants of members may be adopted as full members of the Quechan Tribe, but non-Indians who may be adopted shall have no right to hold tribal office or to receive assignments of land, or otherwise to share in the tribal property. [Emphasis added].Footnote 41

Given the practice of employing blood quantums to govern eligibility for tribal membership, and the fact that tribal membership conferred the right to access tribal assets (especially land), we expect American Indian tribes that controlled a larger share of the value of reservation land to have adopted more stringent blood quantums.

Table 1 reports the results of seven OLS specifications on the determinants of blood quantums. Our dependent variable across all specifications is a tribe’s required blood quantum, which takes values between 0 and 1.Footnote 42 Across all specifications, the coefficient on the share of the market value of land which is owned by the tribal government is positive and statistically significant, consistent with the predicted effect of this variable on the stringency of blood quantums. This effect is large.Footnote 43 An increase in tribal land value share from 0 to 100% (which corresponds to a move from the 10th to the 90th percentile) is associated with an increment in blood requirement of more than 1/4. For comparison, in our sample, 51% of the constitutions have no blood quantum, 2% a 1/8 blood quantum as well as 31% a 1/4 and 16% a 1/2 blood quantum.Footnote 44

In columns 2 through 7, we include several controls to account for potential confounding factors. For instance, the degree of ethnic mixing of a reservation’s population might force a tribe to lower the blood quantum to have any members at all. Since ethnic mixing may have affected the patterns of land ownership on the reservation, failure to control for it would bias the coefficient of our variable of interest. The results show that controlling for ethnic mixing leaves our results virtually unaffected.Footnote 45 We find that its effect on blood quantums is negative and statistically significant in all but one specification.

One may also expect that the need to enforce stringent ethnic requirements would decline the smaller the share of tribal members living on the reservation. This may be because of (a) the children of members not living in the reservation are more likely to be mixed-blooded, (b) a greater portion of members living off-reservation signals that the opportunity cost of living on the reservation is relatively high–i. e., that direct access to tribal resources provides only limited benefits. Our results show that the share of tribal members living on the reservation negatively affects the stringency of the blood quantum, this effect being generally significant across specifications. One potential interpretation is that social norms and extra-constitutional enforcement mechanisms may be a cheaper alternative than strict blood quantums as more of those with access rights live in closer proximity and are likely to interact with one another frequently.Footnote 46

5.2 Direct democracy

We now move to testing our framework’s prediction on the relationship between tribal population size and the choice of direct versus representative democracy. Table 2 reports the results of six logit specifications. In each specification, our dependent variable has value one if a tribe’s constitution established a general council consisting of all adult members as the tribe’s legislative body and zero otherwise. Since we want to maximize variation on the independent variable, we do not restrict our sample to tribes with more than 700 members, as we do for our other empirical tests.

There are two main takeaways from the results in Table 2. First, the coefficient on the value of the share of reservation land controlled by the tribe is negative throughout and generally statistically significant at the 10% or 5% levels. Second, the size of the tribe’s population negatively predicts whether the same tribe adopted a direct form of democratic decision making. The coefficients for “Population” are negative across all specifications and statistically significant at the 10% level in all but one case.

Starting with column 2, our specifications include additional controls.Footnote 47 Except for the share of adults out of the tribal population and one proxy for cultural factors (“Citizen Clothing”), our controls have statistically insignificant coefficients. However, including them tends to make the coefficient on “Population” larger.

Graphing the results from Table 2 for General Council

Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the main results from in Table 2, column 6.Footnote 48 The smallest tribes in our sample had a predicted probability of almost 40% of choosing direct democracy. This predicted probability falls to 20% for tribes of 2,000 inhabitants. The same predicted probability is 35% for tribes with no land held in common and falls to just 6% for American Indian reservations where the tribal government controls all the land.

5.3 Constraining elected officials

According to our framework, tribes will institute stricter constraints on their elected officials the more valuable the assets these officials are entrusted with. To test this hypothesis, we focused on two features of tribal constitutions: Minimum age requirements for the election to the tribal council and term length.Footnote 49

The majority of American Indian constitutions drafted in the aftermath of the IRA stipulated specific age requirements to be eligible to the tribal council.Footnote 50 In some tribes, like the Zuni, a commonly held view was that “[y]oung men are no good leaders. They don’t understand the Zuni way of doing things. One has to be old enough to handle the problems we have.” (Pandey, 1968, 76). Yet the requirements diverge substantially across tribal constitutions. Most of them were either 18, 21, or 25 years old, but some constitutions required tribal councilmen to turn 28 or 30 years old before holding office.Footnote 51 The Chippewa Cree Indians of the Rocky Boy’s reservation in Montana went as far as to require district representatives to be at least 25 years but to require a “Representative at Large” to be “a member at least 65 years of age.”Footnote 52

Table 3, columns 1–4 show the results of OLS specifications with the minimum age to be elected to the tribal council as the dependent variable. Consistent with our framework, tribal land value is positively and statistically significantly associated with a higher minimum age for office eligibility. Columns 2–4 include a set of control variables, none of which appears to have a statistically significant effect on our dependent variable. The one exception is the share of adults out of the reservation’s population. Including these controls leaves the coefficient on “Tribal land value share” virtually unaffected.

There is considerable variation over tribal constitutions’ choice of term lengths for tribal councilmen. From 1934 to 1950, 58% of tribes of more than 700 inhabitants set terms in office for two years. This is unsurprising since the US constitution does the same for members of the House of Representatives. What is surprising, given the circumstances, is that a substantial number of tribes deviated from the example set by the American constitutions, setting terms of one, three, and even four years.

The results in Table 3, columns 5–8, show that the choice of term length by a tribe was negatively affected by the value of the share of reservation land under tribal ownership. As predicted, the more valuable the share of land held by tribal government, the shorter the mandates. While of the right sign, the coefficient for “Tribal land value share” is not significant in column 5. However, including a set of controls increases the coefficient’s magnitude and makes it significant. One control is of particular interest. We examine whether a constitutional text allows for the recall of elected officials. If so, the control variable “Recall” takes a value of 1 and zero otherwise. The coefficient on this variable is positive and statistically significant, suggesting that shorter term lengths and recalls may have worked as substitute institutional solutions to the problem of constraining elected officials.Footnote 53

5.4 Protection of private property

The drafting of a constitution is like any other political process in the ability of interest groups to influence it. Our framework identifies two interest groups: The owners of private or allotted land on the reservation and the other tribal members. Owners gain the most from having their rights recognized and protected by the constitution. On the other hand, tribal leadership and the rest of its members may gain most from seeing the land held in common.

Two reasons suggest that constitutional protections of private property will be stronger the greater the value of land in private hands. First, if the value of resources is greater under private control than under governmental control, private property owners have, everything else being equal, a greater incentive to secure their rights through successful lobbying (Becker, 1983). Second, owners of private assets, and especially land, have a fairly precise idea of what they would lose if they were expropriated. Voters pushing for expropriation, on the other hand, will have to engage in relatively costly collective action as they need to measure the value of the stolen assets as well as to organize how to “share the spoils”–something those lobbying for greater protection of their ownership do not have to do.

Table 4 provides the results of an empirical test of our prediction. Our dependent variable here takes a value of one if a tribal constitution contains a “takings” clause constraining the tribal government’s ability to appropriate privately owned assets without compensation.Footnote 54

Our results support the hypothesis that stronger constitutional guarantees for property rights accompany larger values of privately owned land.Footnote 55 The relationship between the value of privately owned land and the presence of a takings clause is reinforced when we control for whether a constitution was enacted in the aftermath of the IRA or the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act. This is most likely because one common fear on reservations, as they voted on whether to reject the IRA, was that the act would lead to the tribalization of private lands. Footnote 56 Fig. 3 graphical represents the main result from Table 4.

Graphing the results from Table 4 for Takings

The validity of our prediction is further strengthened by looking at the number of times each constitution refers to the right to inheritance and to land allotment.Footnote 57 We should expect inheritance to be relatively more important in tribal constitutions if the value of assets is higher. Given that allotted land is held in trust by the BIA and cannot be alienated, we should also expect greater concerns about inheritance for allotted lands than for those held in fee simple or under tribal control.Footnote 58 Similarly, we should expect more mentions of allotment in the constitutions of tribes where allotted land is more widespread. The results in Table 5 broadly confirm those hypotheses. The coefficients for “Land value per capita,” for instance, indicate a statistically significant effect on the number of mentions of inheritance in a constitutional text. Also, higher land value per capita predicts more mentions of allotment. This is likely because more valuable land was more likely to be allotted in the first place, as Leonard et al., (2020) have shown.

5.5 Validity concerns: unanimity and De Jure vs. De Facto

Our results conform to the predictions of our framework. However, one may question the validity of our exercise on two grounds: (a) that the tribal constitutions in our sample were not consented to unanimously, and (b) that their letter may not have corresponded to tribal practice.

Consider the problem of unanimity first. In their framework, Buchanan & Tullock (1965) assume that decisions over constitutional provisions must be made unanimously. Our application of the framework to tribal constitutions should not be understood to imply that these texts were approved by every member of the respective tribes or that they were in any way legitimate. Indeed, there is evidence to believe that, in a significant portion of cases, IRA constitutions were endorsed by only a minority of those eligible to vote (Crepelle, 2019, 439). Unfortunately, few (if any) real-world constitutions could meet the bar of unanimous approval, which would rule out any application of the framework by Buchanan & Tullock (1965) to the study of real-world constitutions. Fortunately, a sizeable empirical literature finds empirical support for this approach (Crain & Tollison, 1977; Barzel & Sass, 1990; Sass, 1991, 1992; Fahy, 1998; Voigt, 2011). Moreover, the problems associated with the lack of an explicit unanimous endorsement of a constitution are mitigated when those opposed to it face relatively low exit costs, as tends to be the case in small jurisdictions like reservations.

Our predictions focus on the marginal effects of changes in tribal characteristics. These effects are not dependent on the formal decision-making system (i.e., unanimity, majority, oligarchy, dictatorship) that resulted in the constitution. All we assume is that different tribal circumstances affect the relative marginal benefits of the alternative constitutional provisions in systematically different ways. See Sass (1991) and Sass (1992) for applications of a similar approach.

To mitigate this concern, in Appendix G, we replicate all our specifications restricting the sample to only those tribes whose voters adopted their constitutions by a majority of 66% of the vote or more. Our results are robust to using tribes in which a super-majority voted to ratify their IRA constitution.

The second concern with our exercise is that written tribal constitutions may have been the political rules of the game in theory but not in practice. If the gap between nominal and real institutions is large enough, focusing on written tribal constitutional documents will not reveal much about the actual variation in de facto political institutions across reservations. The history of federal interference with internal tribal affairs makes this concern especially pressing. Considering this history, one may suspect that tribal constitutions were imposed onto tribes by the BIA. Since external impositions of institutional change are seldom successful (Boettke et al., 2008), it would be reasonable to question the impact of IRA constitutions.

We find these concerns less troublesome on the following grounds. First, there is evidence that de jure political institutions on the reservation (including constitutions) have long-term effects on a tribe’s economic performance (Cornell & Kalt, 1995; Akee et al., 2015). If the texts of tribal constitutions were not reflective of the actual rules of the game on reservations, they should not systematically affect real variables.

Second, there is reason to believe that, in drafting their constitutions, tribal representatives would have wanted to minimize the “distance” between de jure provisions and de facto practices. Too large a discrepancy between the two would have introduced room for litigation and appeals to the BIA to intervene in internal tribal affairs.

Finally, it is unclear how or why de jure and de facto would differ in relation to the constitutional features we focus on. For instance, such a discrepancy would imply that term lengths are longer in practice than in law or that those below the minimum voting age are allowed to vote anyway. Ultimately, the best test for the hypothesis that written constitutions and tribal practice differ is whether the predictions derived from our framework find support in the data or not. If de jure institutions were but dead letter and this is known to the members of the tribe, they would not have cared one way or the other which provisions they contained. Hence, it would be unlikely for us to find that a tribe’s characteristics predict the content and structure of its constitution.

5.6 Alternative hypotheses

This section discusses some alternative hypotheses that could potentially account for the observed variation in the content and structure of tribal constitutions.

Blood quantums

Rather than a mechanism to avoid a tragedy of the commons, blood quantums may reflect differences in cultural traits between tribes. For instance, different reservations may have different preferences over the homogeneity of their population. More generally, cultural characteristics may also affect a tribe’s willingness to held land and other assets in common, and thus we must try to identify their independent effect. To do so, in Table 1, we alternatively include one of three distinct control variables to account for a tribe’s cultural traits. First, we measure the frequency of references to “culture,” “custom” or “tradition” in each constitutional document.Footnote 59 Our second and third variables measure the portion of tribesmen who spoke English and the portion of tribal members who wore Western-style clothing rather than traditional Indian clothes in 1934.

While none of our measures of a tribe’s cultural characteristics are perfect, they proxy for such things as cultural assimilation and attachment to traditional values, which one expects would correlate with preferences for homogeneity. The coefficients on these controls are never statistically significant from zero, and their inclusion does not affect our overall results.

Direct democracy

Tradition and cultural traits may also be responsible for the choice between direct and indirect democracy. For instance, some tribes had practiced direct forms of democratic participation long before the IRA (Johansen, 1982; Wilkins, 2007,2009). Table 2 shows some evidence for the influence of cultural characteristics on this choice. The share of reservation residents wearing Western-style clothing is negatively related to the odds of direct democracy, suggesting that more traditional tribes were also more likely to adopt it. Nevertheless, the inclusion of cultural controls does not undermine the validity of our hypotheses, and indeed it makes the values of the coefficients on population size larger (in absolute value) and more significant.

Age requirements

When it comes to minimum age requirements, one hypothesis is that they may have resulted from the desire of entrenched tribal interests or the BIA to a subset of the reservation’s population from office, at least in the short run. Unfortunately, our data does not allow us to distinguish this mechanism from the effect of agency costs. One should consider this limitation when assessing our interpretation of the coefficients for tribal land value in Table 3. However, the fact that we find strong evidence that term length for elected officials is negatively correlated with tribal land value further supports the importance of agency costs for constraints on public officials.

Protection of property rights

A concern with our findings on property rights protection is that both the per capita value of privately held land and the adoption of a takings’ clause reflect a third, omitted variable. For example, the two may be caused by a strong traditional norm favoring private property on the reservation. Since stronger property rights tend to increase the value of privately held assets and the adoption of the takings’ close may reflect the same sensibility, the large, positive, and statistically significant coefficient in Table 4 would be suffering from omitted variable bias.

The history of federal policy pertaining to reservation land offers little support for this thesis. First, in most instances, by 1934, American Indian tribes did not live on their ancestral land but on reservations that were often hundreds of miles removed. On these reservations, land had been privatized in the decades that preceded the IRA and only as a result of federal allotment policy aimed at turning Indians into American citizens by way of land ownership and farming. The experience with the allotment system was not a happy one. If anything, this botched attempt at land privatization appears to have had a negative effect on productivity and land values (McChesney, 1990; Dippel et al., 2020).

6 Conclusion

It is something of a cliché in the social sciences that institutions, among which are political institutions, matter. This statement is uncontroversial. If institutional choices were orthogonal to economic performance, then groups would not care much about which “rules of the game” to adopt: One system of government would work just as well, or just as poorly, as any other. Exactly because groups select their political institutions with an eye for their properties, we cannot treat political institutions as exogenous. To understand their direct and independent consequences, we must first understand what caused a group to choose them over plausible alternatives in the first place.

There are significant practical problems with this enterprise (Sass, 1991, 1992). For instance, countries outline their political systems in their constitutions, but these are often the result of the choice of a minuscule share of the country’s overall population, and the outcome may not reflect the interests and characteristics of the public at large. Moreover, for countries lacking separation of powers and checks on the executive, constitutions are little more than cheap talk. This has led some scholars in the past to test theories of constitutional choice on private organizations (Barzel & Sass, 1990; Sass, 1991) or very small jurisdictions like small towns and municipalities (Sass, 1992; Fahy, 1998). In our paper, we look at the choice of political institutions by American Indian tribes, emphasizing the constitutional documents produced in the aftermath of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. American Indians living on reservations were then, and remain today, among the poorest people living in the United States. Under the leadership of John Collier, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) broke with the many-decade-long objective of undermining tribal authority in favor of Indian assimilation in American society and its economy. Instead, the IRA returned tribes at least some authority to govern themselves. There was one condition: Tribes needed to draft and ratify a constitution, which was then voted on by their members and approved by the BIA.

In the years following the IRA, dozens of tribes complied, producing many constitutions. Even as the BIA and the federal government aided in the drafting process, the resulting documents show significant variation–in the “blood” requirements to qualify for membership, the degree of direct democratic participation by members, constraints on elected officials, and protections of individual property. We first provide a theoretical account for such variation and then test our hypotheses against data from American Indian tribal constitutions. We find strong evidence that tribes systematically crafted their political systems in the ways predicted by our framework.

Notes

Blood quantums have a peculiar status in American law. The Supreme Court has generally recognized their legality by framing them as legitimate political, rather than racial, instruments to advance the interests of tribal members. See for instance Morton v. Mancari, 417 S. Ct. 535 (U.S. 1974). However, more recently federal courts have questioned the ability of American Indian polities to use blood quantums to exclude individuals with historical links to a tribe from political participation. In particular, the courts struck down a provision of the Cherokee 2007 constitution denying the Cherokee Freedmen, the descendants of slaves owned by the tribe, the right to vote in tribal elections. See Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash et al., 267 F. Supp. 3d 86 (D.C. 2017). The issue of the relationship between blood quantums, tribal membership, and American Indian sovereignty was also discussed during oral arguments leading up to the recent Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 42 S. Ct. 1612 (U.S. 2022).

In his work on tribal constitutions, Anderson (2016) treats blood quantums as independent variables, finding that they predict the presence of a casino on the reservation. While he does not offer an explanation for this result, our framework suggests that blood quantums prevent the dissipation of rents generated by operating an Indian casino, thus increasing the profitability of this enterprise.

We are not the first to systematically study American Indian constitutions. Using a similar approach, Anderson (2016) looked at the historical determinants of constitutional choice, especially the role of the historical centralization of tribal political organization and the decision of the federal government to force separate bands to merge into one political unit during the removal and reservation period, for which he finds mixed evidence.

Others have pointed out the detrimental role of federal policies such as removal and the allotment system and the IRA (McChesney, 1990; Anderson & Parker, 2008, 2009; Dippel, 2014; Feir et al., 2019; Leonard et al., 2020; Frye & Parker, 2021) argue that legal institutions and whether a tribe has to independent courts are partially responsible for the variation in economic performance between tribes.

Not generally at least. For an exception, see the discussion of the rise of democracy in Ancient Greece in Fleck & Hanssen (2018).

See Driver (2011) for an overview of the political organization of American Indian peoples in the pre-Columbian period.

For instance, by way of cultural influence but also as an unintended outcome of the process of Indian removal.

The IRA was part of a broader change in the federal government’s agenda towards tribal groups known as the “Indian New Deal.“ Due to their peculiar status, Alaskan, Hawaiian, and Oklahoman native groups were excluded from the IRA. However, Congress promptly passed follow-up legislation to address each of these cases. In the case of Oklahoman Indians, the content of this legislation (the Oklahoman Indian Welfare Act of 1936) was largely analogous to the IRA.

The turn was steeper in rhetoric than in practice. For those tribes that opted into the IRA, the BIA maintained significant oversight over the internal affairs of reservations, ultimately to the detriment of tribes’ long-term economic performance (Frye & Parker, 2021).

Of the 258 tribes that voted on the provisions of IRA, over two-thirds did so in the affirmative; in 77 tribes, a majority rejected the initiative (Haas, 1947, 3). Notably, (Crepelle, 2019, 439) has suggested that the BIA’s administration of the votes on the approval of the IRA and the ratification of the new constitutions was in some respects “illegitimate”.

As Kelly (1975, 299) notes, however, federal interference with tribal political and social life was reined in following the IRA: “Between 1933 and 1945 the excessively authoritarian powers of the Indian Bureau and its employees in the field were curbed substantially.

A draft of this model constitution can be found in Cohen (2006).

One hundred and nine tribes were terminated by the federal government during this period (Wilkins, 2007, 120).

See Anderson & Parker (2008) for an evaluation of the consequences of Public Law 280 to American Indian welfare.

For instance, Wilkins (2007, 147-8) discusses the amendment of the Navajo constitution in 1989 to limit the powers of the executive branch.

If a production process is characterized by U-shaped average costs, as is the case for grazing, Johnson & Libecap (1980) argue for an alternative solution: Larger-than-optimal individual herds. The latter functioned effectively as entry-deterring excess capacity, discouraging entry and thus limiting rent-dissipation. However, the resulting rents are smaller than if entry could be otherwise restricted.

Blood quantums were commonplace in colonial America and throughout the first two centuries of United States history, particularly concerning the legal status of African Americans (Spruhan, 2006; Bodenhorn & Ruebeck, 2003) provide an economic explanation for the centrality of blood quantums in early American history.

On this issue, see the discussion by Mueller et al., (2003).

This effect has been found in a wide array of circumstances. For instance, Sass (1991, 75) finds that “[l]arge cities don’t hold town meetings simply because it would be too expensive.”

Notice that with respect to the US Federal government, one needs to be at least 35 years old to be eligible to the presidency but only 30 to become a Senator and 25 for becoming a Representative. This is exactly what our theory predicts. Senators, serving in a chamber with fewer members, have greater political power and more room to act opportunistically.

For instance, Venetians, being extremely fearful of tyranny, developed the habit of nominating elderly Doges during the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Smith et al., 2021).

Hayek (2011) proposed establishing a legislature with a 45 year old minimum age requirement to make sure representatives have a good reputation.

In Federalist 10, Madison argues that “however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that, however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude.”

For instance, socialist countries typically have massive legislatures with more than 1,000 members.

Such expectations were eminently reasonable. John Collier, the head of the BIA between 1933 and 1945, was explicit in his desire to see the effects of the allotment process fully reversed, including the return of allotted land to tribal common ownership (Kelly, 1975).

Many Indian beneficiaries never gained full (“fee simple”) ownership of their land. While they could use the latter as they pleased, they could not sell it without the approval of the BIA. For a discussion of the allotment system and its consequences, see McChesney (1990) and Leonard et al., (2020).

In collecting this information, we treated amended constitutions as separate observations from the original document.

Indeed, reading tribal constitutions, one quickly realizes that the constitutions enacted in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s are substantially different from those drafted from the 1970s onward. Although the evolution of constitutions through time is itself a question worth investigating, we here restrict our attention to a specific period going from 1934 to 1950.

Available online at: https://www.loc.gov/collections/native-american-constitutions -and-legal-materials/ (last accessed on 2/19/2022).

All of the links are available on http://thememoryhole2.org/blog/tribal-constitutions (Last accessed on 2/19/2022).

It is not clear how widespread blood quantums had been among American Indian tribes before the Indian Reorganization Act, in part due to the fact that most of their constitutions had not been written down. One potential cause behind the popularity of blood quantums in the IRA constitutions is that the BIA encouraged tribes to adopt one (Frye et al., 2020). However, formulation from the “model constitution” made available to American Indian tribes by the BIA reads as follows: “The membership of the [blank] Tribe of Indians shall consist of … All persons of Indian blood whose names appear on the official census rolls of the tribe as of April 1, 1935.“ While there is a reference to “persons of Indian blood,“ there is not one to minimum blood quantums. Moreover, there is some evidence that the idea of restricting membership on the basis of blood was not alien to American Indian polities. Cohen (2006) discusses several instances of tribal constitutions from the early decades of the twentieth century that already contain blood quantums. Moreover, the oldest written American Indian constitution, the Great Law of Peace of the Iroquois Nations, already stipulated membership restrictions on the basis of blood: non-Iroquois were excluded from democratic deliberation on the basis that “[aliens] have nothing by blood to make claim to a vote” (Wilkins, 2009, p. 30).

We also used the “hunspell” package in R to check spelling mistakes and correct them.

We used the population figure from that document because it could easily be cross-referenced with the population figures given in Haas (1947).

We use data from 1926 because it enables us to control for tribal characteristics before the IRA.

Inequality in landholding might also have influenced tribes’ constitutional choice. For instance, wealthier residents might have a greater interest in adopting representative over direct democracy or lobby for stronger protections for the rights of allottees. Unfortunately. we do not have the data to control for these potential effects. Thankfully, the allotment system was meant to allocate land equally across Indian residents and restricted sales to third parties, which would have limited the ability to accumulate large holdings, making inequality of this sort less of a concern.

In appendix E, we show that our results are robust to changing our population threshold by including 28 constitutions from smaller tribes.

This constitution, enacted in 1936, is available at: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llscd/37026341/37026341.pdf (Last accessed on 2/20/2022).

Throughout the rest of the paper, we report our results with standard errors doubly clustered at the BIA region and year levels (in parenthesis).

One anonymous reviewer suggested the possibility that more cooperative tribes might be both more productive (which could increase the share of the value of the land held in common) and less likely to adopt strict quantums. In that case, our inability to control for this variable would negatively bias our coefficient on Tribal Land Value Share. If so, our estimates could be considered conservative.

Related to this result, Frye et al., (2020) find economic growth (in some instances generated by the opening of casinos on reservations) led to higher levels of conflict about blood quantum-based membership requirements when tribes are more ethnically diverse.

Our “Mixing,” “Speaks English,” and “Citizen Clothing” variables are also proxies for a tribe’s length of exposure to Europeans. Notice that the effect of the length of exposure to Europeans on blood quantum is unclear as it likely impacts human capital, how embedded a tribe is in the broader society, as well as many other variables. The type of exposure to Europeans–violent or peaceful–may also matter. Here too our cultural variables are useful proxies as tribes facing violent interactions with Europeans are probably more likely to maintain sharply separate cultural traits. For some examples of conflict or relatively peaceful behavior between Indians and settlers, see Candela & Geloso (2021) and Geloso & Rouanet (2020).

To verify the validity of our econometric results, we operate a number of robustness checks in the appendix. First, we use data from Wilson (1935) which measures the portion of reservations covered by tribal land in 1934 (as opposed to its $ value in 1926). The results are included in Appendix B. Second, a few constitutions in our sample, despite being very similar to the other constitutions in style, did not have an Indian Reorganization Act or Oklahoma Welfare Act status. We control for this in Appendix C. Third, we check if our results are robust to changes in our chosen population threshold (Appendix E). Finally, because of the small size of our sample, we check if our results are robust to the exclusion of potential outliers as well as to changes in our chosen date for the end of the sample (1951). For each selected sample with an end date ranging from 1941 to 1951, we follow a “leave one observation out” process by rerunning our main regressions. The results of all these regressions are reported in Appendix F.

We do not add decade or year fixed as it would drop a substantial number of observations.

The predicted probabilities in Fig. 2 have been calculated by assuming that all other independent variables are at their average level.

In a separate set of regressions, we also investigated the determinants of the size of the tribal council, but our results are not statistically significant. This is consistent with Stigler’s (1976, 19) observation that “legislatures […] are remarkably similar and stable in size.” In other words, there may too little variation in the optimal size of legislatures, and our sample may be too small, to identify the effect of the value of tribal assets on the size of tribal councils. To economize on space, we do not report our regressions with the size of the tribal council in the body of the paper. We report those results in Appendix D.

Some tribes also included unique restrictions on voting such as living requirements, perhaps to prevent members living off reservation from taking advantage of the resources held in common. Other considerations, such as avoiding political polarization based on familial allegiances, may have played a role as well. For instance, the 1947 Constitution of the Isleta Pueblo tribe (New Mexico) sets voting age at 21 years old and requires that the individual live independently of his or her parents.

These age requirements may seem fairly low, yet we should keep in mind that American Indian tribes’ demographics was very young in the 1930s. 77% of tribes from our sample enacting a constitution from 1934 to 1950 had minors composing more than 50% of their population in 1926 and 23% more than 60%. Still in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson mentioned in his Special Message to the Congress on the Problems of the American Indian that “‘The average age of death of an American Indian today is 44 years; for all other Americans, it is 65.”

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llscd/36026087/36026087.pdf (Last accessed on 21/2/2022).

Regressions in Table 3, columns 7 and 8 remain statistically significant at the 5% level when removing “Recall” for the “Tribal land value share” variable. The p-value for that variable in column 6 increases to 0.106.

For instance, the 1935 constitution of the Blackfeet tribe in Montana stipulates that “It is recognized that under existing law [allotted] lands may be condemned for public purposes, such as roads, public buildings, or other public improvements, upon payment of adequate compensation.” (Art.VII, Sect. 1). In some rare occasions, tribes went further by inscribing the right to private property into the constitution. In the 1960s the Yankton Sioux in South Dakota went so far as to include that “all operation under this Constitution shall be free from any system of collectivism/socialism under any and all circumstances” (Art.IX, Sect. 1) and recognized “the private enterprise system.” (Art. IX, Sect. 2).

Table 4 does not include controls for cultural characteristics since doing so does not affect the overall results.

Haas (1947, 7) notes that at the time the IRA was passed, “Fantastic rumors were spread, such as: the bill was designed to deprive the Indians of the interests in their lands, to take away their allotments and communize them […].”

References to inheritance include the following words: heir, heirs, inherit, inheritance, inheritances, inherited, inheriting, inherits. References to allotment include the following words: allotment, allotments, allotted, allotting.

See Leonard et al., (2020) for a study about the negative effects of the high fractionalization of land due to the allotment system.

We used the following roots: “cultur–,”tradition–” and “custom–.”

References

Akee, R., Jorgensen, M., & Sunde, U. (2015). Critical junctures and economic development–evidence from the adoption of constitutions among American Indian nations. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(4), 844–861

Alston, E., Crepelle, A., Law, W., & Murtazashvili, I. (2021). The chronic uncertainty of American Indian property rights. Journal of Institutional Economics, 17(3), 473–488

Anderson, R. W. (2016). Native American reservation constitutions. Constitutional Political Economy, 27(4), 377–398

Anderson, T. L. (Ed.). (2008). Unlocking the Wealth of Indian Nations. New York: Lexington Books

Anderson, T. L., & Parker, D. P. (2008). Sovereignty, credible commitments, and economic prosperity on American Indian reservations. The Journal of Law and Economics, 51(4), 641–666

Anderson, T. L., & Parker, D. P. (2009). Economic development lessons from and for North American Indian economies. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 53(1), 105–127

Barzel, Y., & Sass, T. R. (1990). The allocation of resources by voting. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105(3), 745–771

Becker, G. S. (1983). A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(3), 371–400

Becker, S. O. (2022). Forced displacement in history: Some recent research. Australian Economic History Review, 62(1), 2–25

Bodenhorn, H., & Ruebeck, C. (2003). The economics of identity and the endogeneity of race

Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2008). Institutional stickiness and the new development economics.American Journal of Economics and Sociology, pages331–358

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1965). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy (100 vol.). University of Michigan Press

Burke, Chase, H. (1926). Annual report of the commissioner of Indian affairs to the secretary of the interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1926. US Government Printing Office

Candela, R. A., & Geloso, V. J. (2021). Trade or raid: Acadian settlers and native Americans before 1755. Public Choice, 188(3), 549–575

Carlos, A. M., Feir, D. L., & Redish, A. (2022). Indigenous nations and the development of the US economy: Land, resources, and dispossession. The Journal of Economic History, 82(2), 516–555

Cheung, S. N. (1970). The structure of a contract and the theory of a non-exclusive resource. The Journal of Law and Economics, 13(1), 49–70

Clow, R. L. (1987). The Indian reorganization act and the loss of tribal sovereignty: Constitutions on the rosebud and pine ridge reservations.Great Plains Quarterly, pages125–134

Cohen, F. S. (2006). On the drafting of tribal constitutions (1 vol.). University of Oklahoma Press

Committee., U. S. N. R. (1935). Indian Land Tenure, Economic Status, and Population Trends, Part X of the Report on Land Planning. US Government Printing Office

Cookson, J. A. (2010). Institutions and casinos on American Indian reservations: An empirical analysis of the location of Indian casinos. The Journal of Law and Economics, 53(4), 651–687

Cornell, S., & Kalt, J. P. (1995). Where does economic development really come from? constitutional rule among the contemporary Sioux and Apache. Economic Inquiry, 33(3), 402–426

Cornell, S., & Kalt, J. P. (2000). Where’s the glue? institutional and cultural foundations of American Indian economic development. The Journal of SocioEconomics, 29(5), 443–470

Crain, W. M., & Tollison, R. D. (1977). Legislative size and voting rules. The Journal of Legal Studies, 6(1), 235–240

Crepelle, A. (2019). Decolonizing reservation economies: Returning to private enterprise and trade. J Bus Entrepreneurship & L, 12, 413

Dippel, C. (2014). Forced coexistence and economic development: evidence from native American reservations. Econometrica, 82(6), 2131–2165

Dippel, C., Frye, D., & Leonard, B. (2020). Property rights without transfer rights:. A study of Indian land allotment

Driver, H. E. (2011). Indians of North America. Second Edition. University of Chicago Press