Abstract

Gamers represent themselves in online gaming worlds through their avatars. The term “Proteus Effect” (PE) defines the potential influences of the gamers’ avatars on their demeanour, perception and conduct and has been linked with excessive gaming. There is a significant lack of knowledge regarding likely distinct PE profiles and whether these could be differentially implicated with disordered gaming. A normative group of 1022 World of Warcraft (WoW) gamers were assessed in the present study (Mean age = 28.60 years). The Proteus Effect Scale (PES) was used to evaluate the possible avatar effect on gamers’ conduct, and the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short-Form was used to examine gaming disorder behaviors. Latent class profiling resulted in three distinct PE classes, ‘non-influenced-gamers’ (NIGs), ‘perception-cognition-influenced-gamers’ (PCIGs), and ‘emotion-behaviour-influenced-gamers’ (EBIGs). The NIGs reported low rates across all PES items. The PCIGs indicated higher avatar influence in their perception-experience but did not report being affected emotionally. The EBIGs indicated significantly higher avatar influence in their emotion and behaviour than the other two classes but reported stability in their perception of aspects independent of their avatar. Gaming disorder behaviours were reduced for the NIGs and progressively increased for the PCIGs and the EBIGs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The detrimental consequences of excessive gaming across several areas of everyday life (e.g., psychological, inter-personal, and wellbeing; [1]) for a small but significant proportion of gamers has prompted the emergence of formal psychopathological classification [2]. Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) was defined as a tentative disorder needing additional clinical and empirical investigation in Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; [3]). More recently, Gaming Disorder (GD) was formally introduced as a diagnostic category in the latest revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) of the World Health Organisation [4].

Despite these advancements, disagreements and debates considering the diagnostic value of disorder gaming persist [5,6,7]. Furthermore, attention has also focused on the accurate measurement of gaming disorder manifestations, as well as defining and identifying the differences between recreational and addictive gaming [8, 9]. In the light of these definitional and theoretical considerations, it is generally agreed by those in the gaming research field that the diversity of potential adaptive and/or maladaptive gaming effects can be explained by (i) the interaction between individual features and traits of the gamer alongside the effects of the real, (ii) in-game surrounding-environment, and (iii) the structural characteristics of the game ([10,11,12,13]a). Within these broader interactions, the association occurring between players and their in-game representational figures (i.e., their avatars), has been highlighted as a significant (yet under-investigated) factor underlying gamers’ experiences [14]. In particular, the User-Avatar-Bond (UAB) has been theorised as a continuous and counter-influential association and effect (from the player to the game-character, and the other way around; [12]). In addition to its role in disordered gaming, the UAB has been shown to facilitate an important positive potential when utilised in online psychological interventions (e.g., gamified e-health programs) and to play a contributory role to gamers’ real-life conduct [12, 15,16,17].

Avatar and Real-Life Behaviour

The literature in the gaming studies field has suggested that the avatar’s behaviour-conduct in-game may exert an influence in the gamer’s real-life conduct [12]. In particular, it is proposed that unconscious, un-planned, and unintentional manifestations related to the in-game participation, defined as ‘Game Transfer Phenomena’ (GTP) may affect the offline conduct of the gamers [18]. These non-volitional manifestations are supported to entail experiences and cognitions, emotions, and actions [19] starting from physiological sensations experienced in the context of gaming [19] and leading to game-simulated real life conduct, the more gamers invest in their in-game avatar [20].

These experiences appear to inform what is termed in the scientific literature as the ‘Proteus Effect’ (PE; [21]). Ancient Greek myths describe Proteus as the god of transformations, who chose to represent himself with various forms and shapes in order not to be recognised. This enabled him to hide his superficial awareness of the past, present, and future [22]. This similarity across the Proteus’ transformation ability (interestingly when aiming to avoid communicating) prompted Yee and his collaborators (2009) to suggest the term PE to describe the bi-directionally transforming link-attachment between players and their in-game characters. In particular, they highlighted that as players might choose diverse in-game representations (frequently on the basis of their real-life preferred and less preferred characteristics), the avatars may similarly change the gamers’ experience, emotion, and behaviour offline. Previous empirical studies have confirmed these hypotheses suggesting that formative features of avatars, as their height and presentation, influence (to a certain extent) offline reactions [17, 21]. For example, research has demonstrated that gamers with taller avatars experience higher self-esteem, while gamers with more attractive in-game avatars present as more socially confident outside of the game [21].

A Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy Understanding of the Proteus Effect

The effect of PE can be interpreted with the employment of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) principles [23]. CBT suggests that experiences inform perceptions and cognitions that may precipitate and perpetuate emotions, when stimuli and/or conditions related to the past experience are encountered [24]. The quality of the emotions experienced (i.e., negative or positive) informs, in turn, the reactions and the behaviours of the person within the specific context [23]. Consequently, while gaming, experiences related to the self-perception of users may be confounded with those related to their game representation [14]. This may be reinforced by “augmented” real-life dimensions, such as time and social contact, aspects of online games, which (to some extent) may make users neglect the mediating contribution of the online application in their game perception, generating the sense of actually “being there” [13, 25]. This mixture between offline reality and the gaming experience has been conceptualised as the experience of (tele)-presence and (from a CBT perspective) may endorse the game experiences with meaning equally significant to that of real-life experiences (Stavropoulos et al., 2018), and therefore helping define specific emotions and behaviours. Consequently, it could be assumed that the avatar’s identity could effect more the self-perception and behaviour of the gamer, as manifested in the context of PE, the higher the game exposure is. Therefore, excessive gaming patterns, such as those involved in disordered gaming, have been associated with higher PE experiences [12].

Study Aims

To examine the potential association between PE and GD, this research utilised a normative group of World of Warcraft (WoW) players. WoW was primarily chosen because it appeals to a wide and relatively representative gaming audience [26]. Furthermore, it is a rather ‘old’ game (i.e., has been played since its release in 2004) that can accommodate the investigation of the effect of more time-lengthy game participation [27]. It additionally stimulates playing motivations that enhance game-absorption such as online-relationships, progressively higher levels of rewards and challenges, and personalised complex avatar options [26]. Finally, WoW (like many online role-playing games) has been linked to increased inclination for GD behaviours [27, 28].

For the present study, the DSM-5 [3] conceptualization of IGD was preferred over others. IGD has been depicted as the persistent and recurrent gaming engagement, usually along other gamers, leading to clinical impairment and distress over a one-year period. Although disagreements and discussions regarding the definition of IGD persist [29], the DSM-5 IGD description has been the most widely employed in the international academic literature and mental-health procedures [30]. The DSM-5 IGD terminology was particularly preferred in the present study on the basis of: (i) comparability with recent peer-reviewed empirical evidence; and (iii) the provision of well-established psychometric tools, assessed across-cultures and across time [24].

Furthermore, prompted by available evidence suggesting distinct typologies of game participation [31, 32], alongside the therapeutic utility of typologies and profiles of gamers in mental health services [33], the goals of this reserach involved: (i) profiling WoW players based on their PE responses targeting perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and behavioural avatar related influences to the gamer; and (ii) assessing whether different PE typologies are associated with disordered gaming features (APA, 2013).

Finally, an additional goal was to introduce a profile categorisation of gamers’ PE experiences in the context of CBT principles [23]. These involve influences in perceptions, cognitions, emotions, and behaviours in consensus with the cognitive cycle [24]. A PE profiling of gamers could have important diagnostic-value (i.e., capacity to categorise gamers according to their experienced PE aspects), and epidemiological and prevalence value (i.e., proportions of gamers belonging to the suggested profiles), as well as conceptual and theoretical value (i.e., describing the various PE gamer profiles, alongside the clarification of the nature of their differences, both quantitatively and qualitatively).

Methods

Participants

A large sample comprising 1022 WoW gamers was recruited (Mage = 28.60 years, SD = 9.90; average duration of educational attendance = 13.22, SD = 5.28; average duration of internet usage = 16.08, SD = 5.41; average duration of WoW gaming = 8.41, SD = 4.11; average avatar level = 104.99, SD = 22.30, min = 1, max = 129; 19.8% females; 20.6% self-defined as non-heterosexual; 60% were engaged in couples’ relationships; and 26.5% had their significant other also participating in the game). Considering, Z = 1.96, confidence interval 95%, the calculated maximum sampling error was ± 3.07%. Preliminary socio-demographic analyses of the participants is provided in Table 1.

Instruments

Socio-demographic, internet and game use information was collected alongside the main measurement scales listed below.

Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short-Form (IGDS9-SF; [34]). The IGDS9-SF was utilised to examine disordered gaming. The nine scale questions, reflecting the relevant DSM-5 described behaviours with reference to the past calendar year (“Have you jeopardised or lost an important relationship, job or an educational or career opportunity because of your gaming activity?”) are addressed across five-points (1 = never to 5 = very often). Responses are accumulated formulating an IGD rate ranging from 9 (minimum behaviours) to 45 (maximum behaviours). The internal reliability of the scale here was sufficient (Cronbach α = .85).

Proteus Effect Scale (PES; [35]). The PES was employed to measure behavioural effects in reality. The PES involves six items which inform a single dimension that reflects the influence games pose on the user offline (e.g., “I see things differently when I play with another character”). The original measure assessed the extent a gamer identified with his/her in-game character and the effect this posed on him/her whilst gaming. However, amendments were introduced to adapt the measure to the present study. These involved assessing the influence a gamer’s avatar posed on the gamer in reality by addressing the same six questions two times; first, with reference to the game (e.g., “Please respond to the answer that best represents your behaviours and feelings in the game”) and second with reference to real life (e.g., “Please respond to the answer that best represents your behaviours and feelings in your real life”). Items were addressed across five-points (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Points were accumulated twice, first with reference to the game context and second with reference to real life, resulting to scores ranging between 6 and 30 and increased rates reflecting increased PE experiences. The internal consistency rate here resulted to a Cronbach’s α of .89 for real life behaviors (which was employed in the present analyses) and .88 for online behaviours.

Procedure

The ethics committee license from the researchers’ institution was provided before progressing to the online collection. Online data collection was chosen as it is proposed for online gamers, it enables participation of hard to access populations differently and is supported not to vary in quality from paper-and-pencil data collection [36, 37]. The survey was promoted via social media platforms and gaming forums from August 2017 to April 2019. After activating the survey-link, eligible gamers accessed the plain language information statement. Following this, they had to digitally provide informed consent to continue to the online survey assessment (via an on-screen ‘tick box’). No cost or limitations were employed for discontinuing and responses were anonymous and confidential.

Statistical Analyses

Latent Class Profiling-Analysis (LCA) with numeric indicators and automatic random starts (to prevent local maxima) utilizing Mplus 7 [38] was used aligning with available research [39]. The means and variances of the indicators and the profiles’ averages were calculated with the Maximum Likelihood with Robust Standard Errors estimatorFootnote 1 (MLR; [40]). The numeric classes’ indicators’ averages, and variances were free whilst the classes’ variances were restricted to be equal, while the covariances between different profiles were set to 0. The profiles of the structure with the best fit were later regressed to the IGD9-SF score, as well as the different IGD items separately [3].

Results

Number of Classes

The testing of a three-class structure corresponded to a Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin testFootnote 2 (VLMR-LRT; H0 Loglikelihood Value) equal to −11,871.409, with a 2-Time value of 765.98 and a p value of .049 proposing that two profiles were insufficient and that three profiles were required. The bootstrapped parametric likelihood ratio VLMR-LRT, which advances the findings’ robustness [38], informed similar findings. The final structure fit corresponded to an Akaike Information CriterionFootnote 3 (AIC) of 23,028.840, a Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)Footnote 4 of 23,144.013 and a sample-size adjusted BIC of 23,061.467, which were improved to both the one-class and the two-class structures respectively, thus suggesting higher applicability. The four-class model was rejected (although it presented with lower AIC and BIC; see Table 2) because the related VLMR-LRT value was insignificant indicating that three classes were sufficient.

Size of Classes

Regarding the proportions of the three profiles suggested, the final class counts and proportions and the estimated posterior probabilities revealed that approximately 70% were classified as Class 1, 26% were classified as Class 2, and 4% were classified as Class 3.

Classification Quality

The entropyFootnote 5 score for the three classes structure was .974, reaching 1 and being over the cut-off of .76, that corresponds to over 90% accurate classification for structures involving three profiles (and significantly higher .64, lower of which there is a minimum 20% likelihood of inaccurate classification; [44]).

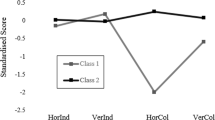

Classes across the Indicators

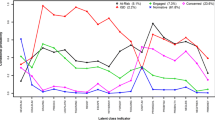

Class 1 means varied in the area of one standard deviation lower of the sample’s means considering all PES items. Therefore, those in Class 1 were defined as ‘non-influenced gamers’ (NIGs) from the avatar class. Class 2 was lower than half standard deviation below the mean on PE Item 1 (“When I play with a different character, I feel different”), and higher than one standard deviation above the mean on Item 3 (“When I play with another character, I feel involved in a different way”) and Item 4 (“The choice of game character determines how I experience things”). Subsequently, those in Class 2 were named as ‘perception-cognition influenced gamers’ (PCIGs) because in relation to their perception and experience they reported influence but in relation to their emotion they did not. Finally, Class 3 was higher than three standard deviations above the mean for Item 1 (‘When I play with a different character, I feel different’) and more than one standard deviation above the mean for Item 2 (‘I behave differently when I play with another character’). Consequently, those in Class 3 were named as ‘emotion and behaviour influenced gamers’ (EBIGs; see Table 3 and Fig. 1).

Classes and Disordered Gaming

To examine the possible links of the three PE classes proposed with GD behaviours, multinomial logistic regression of the three profiles on the disordered gaming score was also conducted. This increased the model fit. The AIC was 22,816.574, the BIC was 22,940.606 and the sample-size adjusted BIC of 22,851.711, which were better than those of the structure including the three classes only. This revealed that adding GD scores increased the model fit. The parameterisation with reference to Class 3 resulted to an odds ratio (OR) of .65 for Class 1 (Standard-Error = .24, p = .006) and of .51 for Class 2 (Standard-Error = .24, p = .030). Accordingly, for every point of increase in GD behaviours, the likelihood of a player being classified as Class 3 instead of Class 1 elevated by .65, while for Class 2 it was .51.

To detect the exact variations between the three classes with reference to the DSM-5 IGD criteria, the profiles were additionally regressed on every single item separately utilizing several multinomial regressions. Membership of Class 3 instead of Class 1 and 2 was associated with DMS-5 ‘tolerance’ criterion 3 “Do you feel the need to spend an increasing amount of time engaged in gaming in order to achieve satisfaction or pleasure?” (Class 3 vs. 2b = .56, p < .001; Class 3 vs. 1b = .91, p < .001), DSM-5 ‘loss of control’ criterion 4 “Do you systematically fail when trying to control or cease your gaming activity?” (Class 3 vs. 2b = .58, p < .001; Class 3 vs. 1b = .68, p < .001), and DSM-5 ‘mood modification’ criterion 8 “Do you play in order to temporarily escape or relieve a negative mood (e.g., helplessness, guilt, anxiety)?” (Class 3 vs. 2b = .23, p = .007; Class 3 vs. 1b = .31, p < .001).

Discussion

The current research assessed a large normative sample of WoW gamers to identify possible PE profiles and their links with GD behaviours. The LCA approach employed in this study illustrated three unique PE classes that (based on their PE characteristics) were described as ‘non-influenced gamers’ (NIGs), ‘perception-cognition influenced gamers’ (PCIGs), and ‘emotion and behaviour influenced gamers’ (EBIGs). The NIGs demonstrated consistently low scores across all PE items assessed referring to the avatar influence in their real life. The PCIGs did not indicate significant emotional and behavioural avatar-related effects, although they reported relatively higher influence in the way they experienced and were involved with real life stimuli. Finally, the EBIGs reported significantly higher emotional and behavioural effects of their in-game characters in reality. The overall number of reported disordered gaming symptoms (as described in DSM-5; [3]) were lower for the NIGs and progressively higher for the PCIGs and the EBIGs. The three IGD criteria of tolerance, loss of control, and mood modification were specifically related to the EBIGs’ PE class.

The Non-influenced Gamer PE Class

The NIG class comprised approximately 70% of the whole sample. NIGs were inclined to report lower perception-cognition, as well as lower emotional and behavioural influences from their in-game characters. Unsurprisingly, these gamers were less likely to present with higher disordered gaming symptoms, as reflected by the nine DSM-5 IGD criteria [3]. The proportion of this profile is important provided the relatively increased average game participation and achievement of the current participants (i.e., over eight years gaming WoW, with a mean avatar level of over 100 that suggests highly engaged players). Subsequently, this supports the contention that higher game engagement and accomplishment may not necessarily make the user behave like their avatar in real life (i.e., higher PE) or disordered gaming as has been indicated elsewhere in the available evidence [27, 45].

The Perception-Cognition Influenced Gamer PE Class

The PCIG class accounted for approximately 26% of all gamers recruited in the present study. PCIGs were inclined to perceive, experience, and involve with real-life stimuli in a way that was somewhat influenced by their in-game characters, but without reporting significant emotional and behaviour-related influences (compared to the other two classes). This supports a perceptive-experiential effect, as described in the initial stage of the CBT sequence (i.e., experience-informing cognitions, which inform feelings eventuating in behaviours; [23]) which is not accompanied by any significant emotional and behavioural reactions. Therefore, although their perception and experience might sometimes converge with their in-game character, their offline-life emotional and behavioural conduct is not particularly influenced by their avatars. Consequently, their indicated GD manifestations, although increased compared to the NIGs, were reduced compared to the EBIGs. Nevertheless, more research is required to confirm these interpretations, likely through qualitative methodologies targeting players of a particular profile.

The Emotion and Behaviour Influenced Gamer PE Class

The EBIG class comprised approximately 4% of all gamers. EBIGs were inclined to report that their real-life feelings and (to a lesser extent) behaviours were influenced by their in-game avatars. This was despite reporting lower perception and experience influences by their in-game character compared to PCIGs. From a CBT cycle perspective, this could indicate that EBIGs experience a higher avatar influence in later stages of the CBT sequence (perceptions and experiences influencing feelings that in turn influence behaviours), and in that context they might be consumed and dominated by these aspects compared to perception-related influences. Consequently, it could be assumed that gamers with this profile might be more be more likely to blur the boundaries between their real life and in-game representation. Unsurprisingly, the EBIGs exhibited with higher levels of GD symptoms, with tolerance, loss of control, and mood modification symptoms being distinctively predictive of this class.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Further Research

The present study has found evidence supporting an important link between PE and GD behaviors. Nevertheless, this finding should be additionally examined in the light of the three separate PE classes (i.e., the NIGs, the PCIGs and the EBIGs). Furthermore, the present results expand and advocate (through quantitative empirical evidence) non-evidence based psychological therapy protocols for GD employing the avatar (i.e., recommended inquiries and reflections about the online identity of gamers and how this compare with their real one; [46]). Therefore, it is recommended that PE manifestations should be taken into consideration in the case formulation of GD behaviours, as well as in their prevention and intervention planning. However, these ideas should be approached in the light of the restrictions of the current research, which employed a community-sourced sample, a cross-sectional design, and self-reporting data collection approach, that might invite potential biases and caveats that undermine the examination of the direction of causality between PE and GD behaviours. Therefore, over-time and mixed methodological designs (involving biological indicators) are necessary to expand the present findings, as well as studies utilising clinical samples, to clearer define and test the profiles supported in the present study and to further elucidate their associations with disordered gaming behaviours.

Notes

Cluster analysis was not preferred as despite providing information about different clusters of gamers, it does not provide information about the overall fit/applicability of the model and the exact chances of a specific gamer being classified into a certain category. Factor analysis was also not utilised as it refers to the extraction of dimensional-continuous latent factors and not categories-profiles, which was the aim here.

This test assesses the model with the number of typologies proposed against a model with one less typology (class). An insignificant Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin test indicates that the assumed number of classes/typologies/profiles is necessary [41].

The AIC is regarded as an information theory goodness of fit measure—applicable when maximum likelihood estimation is used [42]. This index is used to compare different models. Like the chi square index, the AIC also reflects the extent to which the observed and predicted covariance matrices differ from each other. Models that generate the lowest values are optimal.

The BIC is similar to the AIC expressing the log of a Bayes factor of the target model compared to the saturated model and penalises against complex models. Furthermore, a penalty against small samples is included in BIC calculation [42].

Entropy with values approaching 1 indicate clear delineation of classes [43].

References

Anderson EL, Steen E, Stavropoulos V. Internet use and problematic internet use: a systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2017;22(4):430–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2016.1227716.

Scerri M, Anderson A, Stavropoulos V, Hu E. Need fulfilment and internet gaming disorder: a preliminary integrative model. Addict Behav Rep. 2019;9:100144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100144.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth edition). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053.

World Health Organization (2019). International Classification of Diseases 11thEdition: Retrieved on the July 10, 2019, from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en.

Griffiths MD, Van Rooij AJ, Kardefelt-Winther D, Starcevic V, Király O, Pallesen S, et al. Working towards an international consensus on criteria for assessing Internet gaming disorder: A critical commentary on Petry et al. (2014). Addiction. 2016a;111(1):167–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13057.

Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Lopez-Fernandez O, Pontes HM. Problematic gaming exists and is an example of disordered gaming: commentary on: scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 gaming disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). J Behav Addict. 2017;6(3):296–301. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.037.

Jeong H, Yim HW, Lee SY, Lee HK, Potenza MN, Kwon JH, et al. Discordance between self-report and clinical diagnosis of internet gaming disorder in adolescents. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10084. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28478-8.

Jo YS, Bhang SY, Choi JS, Lee HK, Lee SY, Kweon YS. Clinical characteristics of diagnosis for internet gaming disorder: comparison of DSM-5 IGD and ICD-11 GD diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):945. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8070945.

Van Rooij AJ, Ferguson CJ, Colder Carras M, Kardefelt-Winther D, Shi J, Aarseth E, et al. A weak scientific basis for gaming disorder: let us err on the side of caution. J Behav Addict. 2018;7(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.19.

Brand M, Wegmann E, Stark R, Müller A, Wölfling K, Robbins TW, et al. The interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;104:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032.

Griffiths MD, Nuyens F. An overview of structural characteristics in problematic videogame playing. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4:272–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0162-y.

Liew LWL, Stavropoulos V, Adams BLM, Burleigh TL, Griffiths MD. Internet gaming disorder: the interplay between physical activity and user–avatar relationship. Behaviour and Information Technology. 2018;37:558–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1464599.

Stavropoulos, V., Burleigh, T. L., Beard, C. L., Gomez, R., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Being there: a preliminary study examining the role of presence in internet gaming disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-11. Epub ahead of print. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9891-y.

Burleigh TL, Stavropoulos V, Liew LWL, Adams BLM, Griffiths MD. Depression, internet gaming disorder, and the moderating effect of the gamer-avatar relationship: an exploratory longitudinal study. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2018;16:102–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9806-3.

Blinka, L. (2008). The relationship of players to their avatars in MMORPGs: differences between adolescents, emerging adults and adults. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 2(1), 5. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4211/3252

Jones C, Scholes L, Johnson D, Katsikitis M, Carras MC. Gaming well: links between videogames and flourishing mental health. Front Psychol. 2014;5:260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00260.

Ratan RA, Dawson M. When Mii Is Me. Commun Res. 2015;43(8):1065–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215570652.

Dindar M, Ortiz de Gortari AB. Turkish validation of the game transfer phenomena scale (GTPS): measuring altered perceptions, automatic mental processes and actions and behaviours associated with playing video games. Telematics Inform. 2017;34:1802–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.09.003.

Ortiz de Gortari AB, Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. The game transfer phenomena scale: an instrument for investigating the nonvolitional effects of video game playing. Cyberpsychology, Behavior & Social Networking. 2015;18(10):588–94. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0221.

Ortiz de Gortari AB, Oldfield B, Griffiths MD. An empirical examination of factors associated with game transfer phenomena severity. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;64:274–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.060.

Yee N, Bailenson JN, Ducheneaut N. The Proteus effect. Commun Res. 2009;36(2):285–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208330254.

Encyclopaedia Britannica (2019). Proteus, Greek mythology. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Proteus-Greek-mythology

Stavropoulos, V., Cokorilo, S., Kambouropoulos, A., Collard, J. & Gomez, R. (2019a). Cognitive behavioural therapy online for adult depression: a 10 year systematic literature review. Curr Psychiatr Rev,in press.

Stavropoulos, V., Bamford, L., Beard, C., Gomez, R., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019b). Test-retest measurement invariance of the nine-item internet gaming disorder scale in two countries: a preliminary longitudinal study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-18. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00099-w.

Riva, G., Davide, F., & IJsselsteijn, W. A. (Eds.). (2003). Studies in new technologies and practices in communication. Being there: concepts, effects and measurements of user presence in synthetic environments. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press.

Morcos, M., Stavropoulos, V., Rennie, J. J., Clark, M., & Pontes, H. M. (2019). Internet gaming disorder: compensating as a Draenei in world of Warcraft. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-17. Epub ahead of print. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00098-x.

Billieux J, Van der Linden M, Achab S, Khazaal Y, Paraskevopoulos L, Zullino D, et al. Why do you play world of Warcraft? An in-depth exploration of self-reported motivations to play online and in-game behaviours in the virtual world of Azeroth. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(1):103–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.021.

Ghuman D, Griffiths MD. A cross-genre study of online gaming: player demographics, motivation for play, and social interactions among players. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning. 2012;2(1):13–29. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcbpl.2012010102.

Griffiths MD, & Pontes HM. The future of gaming disorder research and player protection: what role should the video gaming industry and researchers play?. Int J Ment Health Ad. 2019;1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00110-4.

Griffiths M, King D, Demetrovics Z. DSM-5 internet gaming disorder needs a unified approach to assessment. Neuropsychiatry. 2014;4(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.2217/NPY.13.82.

Hamari, J., & Tuunanen, J. (2014). Player types: A meta-synthesis. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from: https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/99064/player_types_a_meta_synthesis.pdf?sequence=1

Nagygyörgy K, Urbán R, Farkas J, Griffiths MD, Zilahy, ...Demetrovics, Z. Typology and socio-demographic characteristics of massively multiplayer online game players. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. 2013;29:192–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2012.702636.

Torres-Rodríguez A, Griffiths MD, Carbonell X, Farriols-Hernando N, Torres-Jimenez E. Internet gaming disorder treatment: a case study evaluation of four different types of adolescent problematic gamers. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2019;17(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9845-9.

Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;45:137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006.

Van Looy J, Courtois C, De Vocht M, De Marez L. Player identification in online games: validation of a scale for measuring identification in MMOGs. Media Psychol. 2012;15(2):197–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2012.674917.

Griffiths MD. The use of online methodologies in data collection for gambling and gaming addictions. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2010a;8(1):8–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9209-1.

Weigold A, Weigold IK, Russell EJ. Examination of the equivalence of self-report survey-based paper-and-pencil and internet data collection methods. Psychol Methods. 2013;18(1):53–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031607.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2019). Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: User’s guide, 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Carras MC, Kardefelt-Winther D. When addiction symptoms and life problems diverge: a latent class analysis of problematic gaming in a representative multinational sample of European adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(4):513–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1108-1.

Li CH. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods. 2016;48(3):936–49. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7.

Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008;2(1):302–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x.

Vrieze SI. Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychol Methods. 2012;17(2):228–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027127.

Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif. 1996;13(2):195–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01246098.

Larose C, Harel O, Kordas K, Dey DK. Latent class analysis of incomplete data via an entropy-based criterion. Statistical Methodology. 2016;32:107–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stamet.2016.04.004.

Griffiths MD. The role of context in online gaming excess and addiction: some case study evidence. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2010b;8:119–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9229-x.

Tisseron S. L'ado et ses avatars. Adolescence. 2009;3:591–600.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS: contributed to the literature review, hypotheses formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

Contact: vasilisstavropoylos80@gmail.com

HP: contributed to the theoretical consolidation of the current work and revised and edited the final manuscript.

Contact: contactme@halleypontes.com

RG contributed to the literature review, hypotheses formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

Contact: rapson.gomez@federation.edu.au

BS contributed to the theoretical consolidation of the current work and revised and edited the final manuscript.

Contact: bruno.schivinski@gmail.com

MG contributed to the theoretical consolidation of the current work and revised and edited the final manuscript.

Contact: mark.griffiths@ntu.ac.uk

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors of the present study do not report any conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards – Animal Rights

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Confirmation Statement

Authors confirm that this paper has not been either previously published or submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Copyright

Authors assign copyright or license the publication rights in the present article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stavropoulos, V., Pontes, H.M., Gomez, R. et al. Proteus Effect Profiles: how Do they Relate with Disordered Gaming Behaviours?. Psychiatr Q 91, 615–628 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09727-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09727-4