Abstract

The risk of suicide is significant during the transition of care; the highest in the first few weeks after discharge from a healthcare facility. This systematic review summarizes the evidence for interventions providing care during this high-risk period. In January 2019, PubMed and Scopus were systematically searched using the search terms: Suicide AND (Hospital OR Emergency department) AND Discharge. Articles relevant to interventions targeting suicidal behaviors during the transition of care were selected after the title and abstract screening followed by full-text screening. This review article included 40 articles; with a total patient population of 24,568. The interventions included telephone contacts, letters, green cards, postcards, structured visits, and community outreach programs. An improvement in the engagement of patients in outpatient services was observed but the evidence for suicidal behaviors was conflicting. The reviewed interventions were efficacious in linking patients to outpatient services, reducing feelings of social isolation and helping patients in navigating the available community resources. For patients with repetitive suicidal behaviors, psychosocial interventions such as dialectical behavioral therapy can be helpful. Patients should be followed by targeted interventions based on risk categorization of the patients by using evidence-based tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death and ranked as the second most common among 15-34 years old patients [1]. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 395,000 intentional self-harm injuries in addition to completed suicides in the United States in 2015 [2]. Suicide-related behaviors cost 93.5 billion dollars when accounting for the direct and indirect impact of suicidal behaviors including lost productivity and medical costs [3]. The US National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention aims at preventing suicide by improving the understanding of suicide, identifying its risk factors, enhancing knowledge of interventions, and implementing these interventions [4]. Suicidal behaviors are not linked to a single factor but are associated with a complex interaction of multiple risk factors including but not limited to genetic factors, family history of psychiatric illnesses, social stressors, underlying psychiatric illnesses, history of trauma, personality traits, and cognitive distortions [5].

The risk of suicide is greater during the transition of care to community settings among patients who were admitted for psychiatric reasons [6]. An analysis of 2000 suicides reported that 41% of suicides occurred before the first follow-up appointment in the community after discharge, 25% within 3 months, 1% within the first 12 months, and the remaining 33% occurred thereafter [6]. Numerous other risk factors such as demographic characteristics, social problems, services delivery, and clinical factors have been studied among these patients [6]. The lack of comprehensive outpatient services and discharges against medical advice potentiates the risk of suicide during the transition of care to the community. This becomes critically important in the context of lack of continuing community care, missing their last follow-up appointment, severe symptoms at their final contact, and being out of contact with services at the time of suicide [7].

A comprehensive plan of action can is required to address the needs of these high-risk patients especially after discharge from an inpatient hospital stay to the community [8]. However, it can be challenging to identify the imminent risk of suicide among these patients at discharge, especially in patients with chronic suicidal behaviors [8]. The objective screening instruments like Suicide Stroop Test, Implicit Association Test, and Suicide Trigger Scale can identify high-risk patients and these patients can be linked with outpatient services to cater to their needs [8]. This article reviews the evidence for the interventions implemented in patients after discharge from the hospital or emergency department, and transition to a community setting. The aim is to educate and enhance awareness among clinicians and policymakers about different interventions that can be utilized during the transition of care.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist (Supplementary Table 1).

Eligibility Criteria

Our inclusion criteria:

-

1.

All original studies including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized trials focused on the interventions to target suicidal behaviors after discharge from a medical facility to the community were included.

-

2.

No restriction on race, place, sex, age, ethnicity, or language and publication date were applied.

Our exclusion criteria:

Study designs such as case reports, case series, letter to editors, study protocols, thesis, reviews, commentary, conference papers, abstract-only articles, and book chapters or news articles.

Search Strategy

In January 2019, two electronic databases, PubMed and Scopus, were searched for relevant publications, using the following search terms: Suicide AND (Hospital OR Emergency department) AND (Discharge). The manual search of references and relevant articles for included studies was performed by two independent reviewers.

Study Selection

Search results from the two databases were imported to Endnote ×7 (Thompson Reuter, CA, USA) to remove any duplicates. Two independent reviewers performed title and abstract screening (when available) followed by the full-text screening of the included articles by using the pre-determined eligibility criteria. In the case of disagreement, the consensus was reached by discussion among reviewers or guidance from a senior reviewer (SN).

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted the data for the first author, year of publication, study design, the summary of intervention and the outcomes of interest, results, and limitations. Data were cross-checked for accuracy by the senior author (SN).

Results

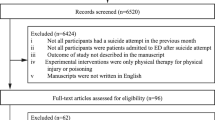

Out of 768 articles after an electronic and manual search, the title and abstract screening were performed resulting in the exclusion of 706 articles. The full-text screening of 62 articles led to the inclusion of 40 articles. PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1), summarizes the screening process for this review article. There were 30 RCTs, eight non-randomized or clinical trials, one cohort study, and one descriptive analysis with a total patient population of 24,568. Tables 1, 2, and 3 provide a summary of these interventions in descending order of year of publication.

Postcards, Green Cards, Letters and Crisis Cards

Morgan et al. (1993) conducted an RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of green cards in the repetition of suicidal behaviors. The green cards provided to patients indicated that a physician was available at all times and encouraged them to seek help during future crises. The suicide repetition rate was 8.56% lower in the experimental group compared to the control group. Fifteen patients in the experimental group used a green card to receive services [9]. An RCT by Cotgrove et al. (1995) studied the efficacy of green cards in preventing suicide in an adolescent population aged ≤16. Out of the 105 patients, 47 received a green card. Of these patients, three (6%) attempted suicide in the year following their discharge, compared to seven patients (12%) who attempted suicide in the control group. Five patients used their green cards to get re-admitted. Although there was a lower rate of suicide attempts observed in the intervention group, the differences between the groups did not reach a statistical significance (p = 0.26) [10].

Evans et al. (1999) investigated the effect of offering emergency telephone support on deliberate self-harm (DSH) repetition. Out of 827 patients, 417 received a green card entailing them to telephone support by a trainee psychiatrist to address any crisis that occurred in the six-month post-discharge. This study reported a comparable benefit for the intervention (16.8%) and control (14.4%) group for DSH (OR 1.20. 95% CI 0.82-1.75) [11]. In another RCT, Evans et al. evaluated the effectiveness of crisis cards in the repetition of DSH. The results were similar to their previous study [11]. In this 12-month follow-up study, there was no overall benefit for DSH (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.85-1.67) [13].

Motto et al. (2001) studied the efficacy of a long-term contact program via letters for suicidal behaviors. These letters were sent monthly for four months, every two months for eight months, and finally every three months for four years (a total of 24 letters for five years). In this study, 843 hospitalized patients with a depressive episode and/or suicidal ideation were randomized into an experimental group (n = 389) and a control group (n = 454). The intervention group had a lower suicide rate at study endpoint, especially in the first two years (p = 0.04) [12].

Carter et al. investigated the efficacy of postcards in reducing repetitions of hospital-treated deliberate self-poisoning (DSP) over a follow-up period of one [14], two [15] and five [20] years. Participants (n = 772) were randomized into an intervention group (n = 378) and a control group (n = 394). The intervention group received a total of eight postcards in a one year span at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 months after discharge. Although the rate of hospital-treated-self-poisoning events was reduced by 50% over a 1-year, 2-years and 5-years period in the intervention group, there was no significant reduction in the proportion of individuals with a history of repetitive DSP [14, 15, 20].

Beautrais et al. examined the effect of postcard intervention in reducing DSH in patients with suicidal behaviors. 174 participants received treatment as usual (TAU), whereas 153 participants received TAU plus postcard intervention. The intervention comprised six mailed postcards in the first year following discharge; at 2 and 6 weeks and later at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. The results showed no significant differences between the groups, in proportion as well as in the total number of participants re-presenting with self-harm to the ED (OR 0.932, p > 0.75) [16].

Hassanian-Moghaddam et al. assessed the efficacy of a postcard intervention to reduce suicidal behaviors such as ideation, attempts and self-cutting/mutilation in a follow up of 12 and 24 months in two separate RCTs [17, 22]. Patients received postcards by mail at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 months after discharge. Although there was a reduction in suicidal ideation and attempts in the intervention arm, there was no observed difference in self-cutting or self-mutilation behaviors [17, 22].

Robinson et al. (2012) also studied the efficacy of postcards among patients aged 15-24.Monthly postcards were sent for 12 months after discharge. The rates of suicide attempts, suicidal ideations and DSH were comparable among the intervention and control group at 12 and 18 months [18]. Kapur et al. compared the intervention comprising of leaflet listing sources of help, two telephone calls soon after the presentation and a series of letters over 12 months to TAU in adults presenting with self-harm. In the intervention group, the 12-month repeat rate was 34.4% compared to 12.5% for the TAU group (p = 0.046). The reasons causing an increased repeat rate in the interventional group versus the control are unclear. There were also a higher number of episodes of repeat self-harm over the 12 months in the intervention group (41 v. 7, incidence rate ratio = 5.86, 95% CI 1.4-24.7, p = 0.0016) [19]. Bennewith et al. conducted a feasibility study for support letters in high-risk patients. Eight letters were mailed at 1, 2 and 4 weeks and later at 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 months following discharge. Most patients felt that they were adequately supported while some preferred fewer letters [21].

Telephone Contact

Cedereke et al. investigated the effect of repeated telephone contacts on treatment attendance, repetition of suicidal behaviors, and mental health in the year after a suicide attempt. Patients (n = 107) received a telephone call at 4 and 8 months following discharge from a medical emergency inpatient unit while 109 subjects received TAU. Fourteen participants (17%) in the intervention group had repetitive suicidal attempts compared to 15 participants (17%) in the control group [23]. In 2006, Vaiva et al. evaluated the effectiveness of telephone calls for repetitive suicidal attempts. Patients with suicidal ingestions were randomly assigned to three different groups who had telephone contact at one month in the first group, three months in the second group, and no telephone contact in the control group. There were significantly lower numbers of suicide attempts in the group that received a telephone call after one month compared to the control group (12% vs 22%). For the patients contacted at three months, the difference was not significantly lower than the control group (17% vs 22%, p = 0.27) [24].

Fleischmann et al. conducted an RCT on 1867 patients with suicide attempt presenting to the ED in five different countries. The intervention group received standard one hour individual educational closer to discharge as well as nine follow-up contacts (phone calls or visits) during the 18 month period at 1,2,4,7, and 11 weeks and 4,6,12, and 18 months. At the end of the study, significantly fewer deaths from suicide occurred in the BIC than in the TAU group (0.2% versus 2.2%, respectively; P < 0.001) [25]. Bertolote et al. continued the RCT of Fleischmann et al. to for an 18-months follow up study to evaluate rates of repeated suicide attempts in the same patient population. The proportion of subjects with repeated suicide attempts was similar in the BIC and TAU groups (7.6% vs. 7.5%, p = 0.909), but there were differences in rates across the five sites. No significant differences were observed between the intervention and control groups at study endpoint, contrary to the initial encouraging decline of suicide mortality previously reported by Fleischmann et al. [25, 26]

Hassanzadeh et al. compared the effect of brief intervention and contact (BIC) to TAU on the repetition of suicidal attempts. The participants were followed up by phone calls or visits at 1, 2, 4, 7, and 11 weeks, 4 months, and 6 months after discharge. BIC did not significantly reduce the repeated suicide attempts, but the patients’ need to get support increased significantly (alpha value = 63.67, p < 0.001) compared to the TAU. The patients in the BIC group tried to get support from outpatient/inpatient services, relatives, friends or by telephone contact to a significantly larger extent (alpha value = 69.2, p < 0.001) compared to the patients receiving TAU [27].

In a study by Chen et al., 15 participants were contacted by text messages in the first week after discharge followed by once a week during the first month, for a total of four contacts. Twelve patients reported the text message acceptable and helpful way of communication with an interest in continuing to receive them for a longer duration [28]. Vijayakumar et al. conducted an RCT to determine the efficacy of BIC in reducing subsequent suicidal behaviors. In this study, 302 participants were randomized to BIC and 320 to the control group. Eight patients attempted suicide in the BIC group compared to the 17 in the control group (OR = 17.3, CI = 10.8 – 29.7). One patient completed suicide in the intervention group and nine in the control group (OR = 35.4, CI = 18.4 - 78.02). Most importantly, the interventions were liked by the participants [29].

In an RCT, Asarnow et al. evaluated the usefulness of Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention (FISP) for utilizing outpatient mental health resources after discharge. FISP consisted of a brief session with youth and their families in the ED to focus on a safety plan. It was supplemented by follow-up calls made within the first 48 h after discharge and then as needed calls at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after discharge. Intervention patients were significantly more likely to attend outpatient treatment, as compared to usual ED-Care patients (92% vs 76%, p = .004). The intervention group also had a significantly higher rate of psychotherapy (76% vs 49%; p = 0.001); combined psychotherapy and medication (58% vs 37%; p = 0.003); and significantly more psychotherapy visits (mean 5.3 vs 3.1; p = 0.003) [30].

A case-control study by Cebria et al. evaluated the usefulness of a telephone contact program in patients discharged from the ED following a suicide attempt. Intervention group (n = 296 received a telephone call after 1 week followed by contacts at 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12-month intervals. The patients in the control group (n = 218) received TAU during the 1-year follow-up. There was a delay in suicide reattempts in the intervention group compared to the baseline year (mean time in days to first reattempt, year 2008 = 346.47, SD = 4.65; mean time in days to first reattempt, year 2007 = 316.46, SD = 7.18, p < 0.0005) and compared to the control population during the same period (mean time in days to first reattempt, treatment period = 346.47, SD = 4.65; mean time in days to first reattempt, pre-treatment period = 300.36, SD = 10.67; p < 0.0005). The intervention reduced the rate of patients who reattempted suicide in the experimental population compared to the previous year (intervention 6% (16/296) v baseline 14% (39/285), difference = 8%, (95% CI =2% to 12%) and to the control population (intervention 6% (16/296) v control 14% (31/218) difference = 8%, (95%CI = 13% to 2%) [49].

Cebria et al. contacted the participants again after five years in order to evaluate the benefit of telephone contacts on suicidal behaviors in a long-term study. No statistically significant difference was observed in the number of people who reattempted suicide after 5 years (intervention group: 31.4% vs control group: 34.4%). The results, thereby indicating that the beneficial effects of telephone contact at one year were not maintained after 5 years [34]. Hughes et al. conducted an RCT investigating the feasibility of FISP in improving the probability of follow-up treatment for suicidal youths. This intervention was effectively delivered in the emergency department for 80.9% of patients [32].

Stéphane Amadéo, et al. conducted an RCT intervention for non-fatal suicidal behaviors in TAU or TAU plus BIC groups. The results showed no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the number of presentations to the hospital for repeated suicidal behaviors [33]. Mouaffak, et al. tested the effectiveness of a follow-up plan OSTA (organization of suitable monitoring for suicide attempters) over a period of one year. On an intention to treat basis, the proportion of patients who reattempted suicide did not differ significantly between the interventional group 14.5% (22/152) and the control group 14% (21/150) [35]. In a controlled study, Exbrayat et al. evaluated the efficacy of a protocol of telephone follow-up of 436 patients at 8, 30, and 60 days after they were treated for an attempted suicide. In the intervention group, repeated suicide attempts were significantly fewer (55/436) compared to the control (69/387) group after the initial index episode (P = 0.037). The interval between the index episode and the first repeated suicide attempt was 143.9 days (± 105.3) in the intervention group and 107.0 days (± 105.2) in the control group (P = 0.05) [36].

Normand et al. conducted a study on a cohort of 173 adolescents and young adults admitted for a suicide attempt. The cohort was re-contacted using phone calls at one week, one month, six months and twelve months after discharge. At one year follow-up, 23 participants (13.3%) had re-attempted suicide. However, only 93 participants were available for contact for follow-up phone calls. Feedback showed that the intervention was considered supportive of the patients and their families [50]. A descriptive study by Berrouiguet et al. reported three selected patients (out of the 244 recruited patients) who received text messages at 48 h after discharge, then at day 8 and 15, and then at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 months. One patient contacted the emergency crisis support service immediately after receiving text messages, while the other two participants contacted up to six days following the text message [38].

Structured Outpatient Service

Donaldson et al. conducted a non-randomized trial in an adolescent population of 23 patients with suicidal behaviors. The participants and their families verbally agreed to participate in at least four psychotherapy sessions and three phone interviews over an eight-week period. The results were compared to the 78 patients in the control group at the study endpoint. The experimental intervention resulted in fewer outpatient psychotherapy ‘no shows’ (9% vs. 18%) and a trend toward a greater number of sessions attended (5.5 vs. 3.9). There were no re-attempts in the experimental group as compared to 9% in the comparison group [39]. A cluster RCT study by Bennewith et al. examined the effect of sending letters from the general practitioners (GPs) to patients who were admitted after an episode of self-harm. At one year follow-up after the index episode of self-harm, no significant difference in the incidence of DSH episodes was observed in the intervention and control groups (odds ratio = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.9 to 1.5) [40].

Currier et al. conducted an RCT investigating the efficacy of the Mobile Crisis Team (MCT) or an Outpatient Mental Health Clinic (OPC) as a follow-up for patients discharged from the ED after an attempted suicide. Successful first clinical contact after ED discharge occurred in 39 of 56 (69.6%) participants randomized to the MCT versus 19 of 64 (29.6%) to the OPC (relative risk 1/4 2.35, 95% CI 1/4 1.55–3.56, p < 0.001). There was some early improvement after discharge in both groups but this efficacy was not observed for symptomatic improvement or repeated ED admissions [41].

Hvid et al. conducted an RCT to investigate the efficacy of the OPAC program (outreach, problem-solving, adherence, continuity) in patients with attempted suicide over a period of six months. The intervention included active outreach with nurse home visits as well as other forms of contact, such as telephone and text messaging. There was a significant lower repetition rate in the intervention group, where the proportion of repetitive patients fell from 34% to 14% (p = 0.005). There were also fewer suicidal acts, in total 37 acts in 58 patients in the control group and 22 acts in 93 patients for the intervention group. The rate ratio for intervention was 0.3185 (95% CI 0.2078-0.4881) [51]. Another RCT by Chen et al. evaluated the benefit of crisis postcards with case management (CM) in the prevention of further suicide attempts. Patients were contacted via phone and at least six CM services were provided over the next three months. Thereafter, crisis postcards were provided with strategies to cope and provide psychological support in times of crisis. The intention-to-treat analysis indicated that the crisis postcard had no effect (hazard ratio = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.56 – 1.29), whereas the per-protocol analysis showed a strong benefit for the crisis postcard (hazard ratio = 0.39; 95% CI = 0.21 – 0.72). Although this study could not provide a significant advantage of adding crisis postcards to case management in the prevention of suicide attempts, further studies are needed to clarify [43].

Simpson et al. conducted an RCT to investigate the role of a peer support group in suicide prevention. In this four-week-long trial, 23 patients received a peer support group compared to the 23 participants in the TAU group. No significant difference was seen between the intervention and control group on the Beck Hopelessness Scale (U = 177, P = 0.083), Quality of Life Scale (U = 238.00, P = 0.732) and UCLA Loneliness scale (U = 236.5, P = 0.724) [44]. A study by Currier et al. tested the effectiveness of combining a Safety Planning Intervention with structured follow-up among Veterans at risk for suicide, seeking treatment at Veteran Affairs Medical Center ED. In safety planning, participants were given a list of coping skills and support systems in the time of crisis in a 20-40 min session. Follow-up contact was made at 72 h and thereafter. The participants in the intervention group were more likely to adhere to outpatient treatment and had 45% fewer suicidal behaviors [45].

Grimholt et al. conducted an RCT to assess the effect of systematic follow-up by GPs to decrease suicidal behaviors and psychiatric symptoms. The intervention group received a follow-up within a week after discharge, once a month for 3 months and 2 consultations in the next 3 months. There were no significant differences between the groups in SSI, BDI or BHS mean scores or change from baseline to three or six months. During follow-up, self-reported DSP was 39.5% in the intervention group vs. 15.8% in controls (p = 0.009). Readmissions to general hospitals were similar (13% in both groups, P = 0.963), while DSP episodes treated at EMAs were 17% in the intervention group and 7% in the control group (p = 0.103) [46]. Another study by Grimholt et al. investigated the effect of follow-up by GPs on adherence to and satisfaction with treatment after discharge from the ED. This study showed a positive response with a higher level of satisfaction observed among patients in the intervention group. Patients in the intervention group received significantly more consultations than the control group (mean 6.7 vs. 4.5 (p = 0.004)). The intervention group was significantly more satisfied with the time their GP took to listen to their personal problems (93.1% vs. 59.4% (p = 0.002)) and with the fact that the GP included them in medical decisions (87.5% vs. 54. 8% (p = 0.009)). The intervention group was significantly more satisfied with the treatment in general than the control group (79% vs. 51% (p = 0.026)) [47] Scanlan et al. evaluated the efficacy of a six to eight-week peer-delivered support program following discharge from an inpatient psychiatric unit. The participants experienced improvement in clinical and functional recovery as well as self-reported decreased readmission days [48].

Discussion

This review article summarizes the evidence for interventions to address suicidal behaviors during the transition of care after discharge from the medical facilities. These interventions included green cards, letters, crisis cards, postcards, telephone-based interventions, BIC, FISP, MCT, OPAC, support through peer support workers, and engagement with outpatient providers. The outcomes of interest were suicidal ideations and attempts, DSH, DSP, and utilization of outpatient services. Despite the higher engagement of participants in outpatient services, the evidence for suicidal behaviors is mixed in these studies.

In this article, 12 studies assessed for engagement in outpatient services and subjective feedback for these interventions. Of these, nine studies reported favorable evidence for engagement in outpatient services with one study reporting no benefits. All studies received positive feedback from the participants. The utilization of outpatient services is critical since participants are at a higher risk during the transition of care, especially during the first three months [6]. This risk is potentiated in patients who leave the care facility against medical advice due to the prevalent stigma towards mental health issues. About 75% of individuals do not engage in outpatient services during the transition of care [25].

In addition to existing stigma, patients with mental illnesses lack sufficient social support and communication skills predisposing them to suicidal behaviors [21, 52]. Well-planned interventions provide a multitude of benefits ranging from psychosocial counseling to CM and monitoring of suicidal behaviors. These interventions create a feeling of connectedness, reduce social isolation, and provide an opportunity to connect with an active listener [21, 52]. A study estimated that approximately 6.3 adolescents would need to engage in FISP to prevent one adolescent from failing to receive outpatient services [30]. This clinically meaningful advantage reinforces the need to engage in outpatient services to prevent the worsening of mental health illnesses, reduce suicidal behaviors and lower rates of recidivism.

The reviewed interventions have conflicting evidence for outcomes related to suicidal behaviors including suicidal ideations and suicidal attempts, DSH, and DSP. Out of 17 studies assessing suicidal attempts and DSP, nine studies had an improvement in suicidal attempts and DSP. Only four studies out of nine suggested an improvement in suicidal ideations. However, the evidence was minimal for DSH with only three studies suggesting a favorable response. The methodological issues such as missing data, differences in baseline severity among study groups, and lack of reliable definition of DSH are potential issues. There was also a differential response to these interventions in patients with first-episode of suicidal behaviors compared to patients with a history of repetitive suicidal behaviors [12]. This necessitates the need for subgroup analyses of the participants due to the differences in baseline severity of psychiatric symptoms and heterogeneity of the patient population. Patients with chronic suicidal ideations and behaviors are more likely to benefit from specialized psychotherapeutic treatment such as dialectal behavioral therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy [12].

A low cost and effective targeted intervention improves suicide-related outcomes and has considerable public health benefits. In a study, the costs of the postcards, telephone outreach, and CBT-based intervention was compared to TAU [53]. The treatment costs and mortality benefits were favorable for postcard interventions compared to TAU [53]. The population impact of these interventions was limited due to the low sensitivity of detecting suicide risk of each patient and the limitations of the healthcare system [53]. This highlights the importance of targeted screening tools followed by evidence-based intervention for high-risk patients during the transition of care.

This review article has several limitations. First, this is a narrative review lacking quantitative analysis of the interventions. Second, as this article included both randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, it was challenging to use a uniform quality assessment tool for all studies. However, the authors have attempted to summarize the limitations of all studies in their relevant tables. Third, a robust search strategy was employed to screen articles relevant to our topic of interest, it is likely that we missed a few evidence-based interventions due to the narrative nature of this review article.

To conclude, patients are at a high suicide risk during the transition of care from medical care facilities to the community setting, especially during the first three months. Several interventions address this challenging public health issue. The reviewed interventions were efficacious in linking patients to outpatient services, reduce feelings of social isolation, and help patients better navigate the available community resources. There was conflicting evidence for outcomes related to suicidal behaviors with lesser evidence for patients with repetitive suicidal behaviors. This highlights the importance of psychosocial interventions such as dialectical behavioral therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy but not limited to these two only. Hospitalization should be followed by targeted interventions based on risk categorization of the patients by using evidence-based tools.

Conclusion

Patients are at a higher risk during the transition of care from medical care facilities to the community setting, especially during the first three months. Several interventions have been designed to address this challenging public health issue. The interventions reviewed in this article were found to be efficacious for linking patients to outpatient services as they reduce feelings of social isolation, and help patients navigate the community resources available to them. There was conflicting evidence for outcomes related to suicidal behaviors with lesser evidence for patients with repetitive suicidal behaviors. This highlights the importance of targeted psychosocial interventions such as dialectical behavioral therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy but not limited to these two only. Hospitalization should be followed by targeted interventions based on risk categorization of the patients by using evidence-based tools.

References

Organization WH. Suicide. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide. Published 2018. Accessed.

CDC. National center for injury prevention and control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). CDC. www.cdc.gov/ injury/wisqars/index.html. Published 2015. Accessed.

Shepard DS, Gurewich D, Lwin AK, et al. Suicide and suicidal attempts in the United States: costs and policy implications. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(3):352–62.

Office of the Surgeon G, National Action Alliance for Suicide P. Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. In: 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action: A Report of the U.S. Surgeon General and of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. Washington (DC): US Department of Health & Human Services (US); 2012.

Naveed S, Qadir T, Afzaal T, et al. Suicide and its legal implications in Pakistan: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9(9):e1665.

Crawford MJ. Suicide following discharge from in-patient psychiatric care. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10(6):434–8.

Dar K, Bhullar D, Dar S, et al. Suicide during transition of care: a narrative review of the literature. Psychiatr Ann. 2019;49:409–141.

Galynker I, Zimri Y, Jessica B. Assessing risk for imminent suicide. Psychiatr Ann. 2014;44(9):431–6.

Morgan HG, Jones EM, Owen JH. Secondary prevention of non-fatal deliberate self-harm. The green card study. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:111–2.

Cotgrove A, Zirinsky L, Black D, et al. Secondary prevention of attempted suicide in adolescence. J Adolesc. 1995;18(5):569–77.

Evans MO, Morgan HG, Hayward A, et al. Crisis telephone consultation for deliberate self-harm patients: effects on repetition. B J Psychiatry. 1999;175:23–7.

Motto JA, Bostrom AG. A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(6):828–33.

Evans J, Evans M, Morgan HG, et al. Crisis card following self-harm: 12-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. B J Psychiatry. 2005;187:186–7.

Carter GL, Clover K, Whyte IM, et al. Postcards from the EDge project: randomised controlled trial of an intervention using postcards to reduce repetition of hospital treated deliberate self poisoning. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2005;331(7520):805.

Carter GL, Clover K, Whyte IM, et al. Postcards from the EDge: 24-month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for hospital-treated self-poisoning. B J Psychiatry. 2007;191:548–53.

Beautrais AL, Gibb SJ, Faulkner A, et al. Postcard intervention for repeat self-harm: randomised controlled trial. B J Psychiatry. 2010;197(1):55–60.

Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Sarjami S, Kolahi AA, et al. Postcards in Persia: randomised controlled trial to reduce suicidal behaviours 12 months after hospital-treated self-poisoning. B J Psychiatry. 2011;198(4):309–16.

Robinson J, Yuen HP, Gook S, et al. Can receipt of a regular postcard reduce suicide-related behaviour in young help seekers? A randomized controlled trial. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6(2):145–52.

Kapur N, Gunnell D, Hawton K, et al. Messages from Manchester: pilot randomised controlled trial following self-harm. The British Journal of Psychiatry: the Journal of Mental Science. 2013;203(1):73–4.

Carter GL, Clover K, Whyte IM, et al. Postcards from the EDge: 5-year outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for hospital-treated self-poisoning. BJ Psychiatry. 2013;202(5):372–80.

Bennewith O, Evans J, Donovan J, et al. A contact-based intervention for people recently discharged from inpatient psychiatric care: a pilot study. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(2):131–43.

Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Sarjami S, Kolahi AA, et al. Postcards in Persia: a twelve to twenty-four month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial for hospital-treated deliberate self-poisoning. Arch Suicide Res. 2017;21(1):138–54.

Cedereke M, Monti K, Ojehagen A. Telephone contact with patients in the year after a suicide attempt: does it affect treatment attendance and outcome? A randomised controlled study. European Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):82–91.

Vaiva G, Vaiva G, Ducrocq F, et al. Effect of telephone contact on further suicide attempts in patients discharged from an emergency department: randomised controlled study. BMJ. 2006;332(7552):1241–5.

Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, Wasserman D, et al. Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: a randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(9):703–9.

Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, et al. Repetition of suicide attempts: data from emergency care settings in five culturally different low- and middle-income countries participating in the WHO SUPRE-MISS study. Crisis. 2010;31(4):194–201.

Hassanzadeh M. Khajeddin N, Nojomi M, et al. brief intervention and contact after deliberate self-harm: an Iranian randomized controlled trial. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2010;4(2):5–12.

Chen H, Mishara BL, Liu XX. A pilot study of mobile telephone message interventions with suicide attempters in China. Crisis. 2010;31(2):109–12.

Vijayakumar L, Umamaheswari C, Shujaath Ali ZS, et al. Intervention for suicide attempters: a randomized controlled study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53(3):244–8.

Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, et al. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1303–9.

Cebria AI, Parra I, Pamias M, et al. Effectiveness of a telephone management programme for patients discharged from an emergency department after a suicide attempt: controlled study in a Spanish population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;147(1–3):269–276.

Hughes JL, Asarnow JR. Enhanced mental health interventions in the emergency department: suicide and suicide attempt prevention in the ED. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2013;14(1):28–34.

Amadeo S, Rereao M, Malogne A, et al. Testing brief intervention and phone contact among subjects with suicidal behavior: a randomized controlled trial in French Polynesia in the frames of the World Health Organization/suicide trends in at-risk territories study. Ment Illn. 2015;7(2):5818.

Cebria AI, Perez-Bonaventura I, Cuijpers P, et al. Telephone management program for patients discharged from an emergency department after a suicide attempt: a 5-year follow-up study in a Spanish population. Crisis. 2015;36(5):345–52.

Mouaffak F, Marchand A, Castaigne E, et al. OSTA program: a French follow up intervention program for suicide prevention. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(3):913–8.

Exbrayat S, Coudrot C, Gourdon X, et al. Effect of telephone follow-up on repeated suicide attempt in patients discharged from an emergency psychiatry department: a controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):96.

Normand D, Colin S, Gaboulaud V, et al. How to stay in touch with adolescents and young adults after a suicide attempt? Implementation of a 4-phones-calls procedure over 1 year after discharge from hospital, in a Parisian suburb. L'Encephale. 2018;44(4):301–307.

Berrouiguet S, Larsen ME, Mesmeur C, et al. Toward mHealth brief contact interventions in suicide prevention: case series from the suicide intervention assisted by messages (SIAM) randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(1):e8.

Donaldson D, Spirito A, Arrigan M, et al. Structured disposition planning for adolescent suicide attempters in a general hospital: preliminary findings on short-term outcome. Arch Suicide Res. 1997;3(4):271–82.

Bennewith O, Stocks N, Gunnell D, et al. General practice based intervention to prevent repeat episodes of deliberate self harm: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2002;324(7348):1254–7.

Currier GW, Fisher SG, Caine ED. Mobile crisis team intervention to enhance linkage of discharged suicidal emergency department patients to outpatient psychiatric services: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(1):36–43.

Hvid M, Vangborg K, Sorensen HJ, et al. Preventing repetition of attempted suicide--II. The Amager project, a randomized controlled trial. Nordic journal of psychiatry. 2011;65(5):292–298.

Chen W-J, Ho C-K, Shyu S-S, et al. Employing crisis postcards with case management in Kaohsiung, Taiwan: 6-month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for suicide attempters. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):191.

Simpson A, Flood C, Rowe J, et al. Results of a pilot randomised controlled trial to measure the clinical and cost effectiveness of peer support in increasing hope and quality of life in mental health patients discharged from hospital in the UK. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:30.

Currier GW, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Rationale and study protocol for a two-part intervention: safety planning and structured follow-up among veterans at risk for suicide and discharged from the emergency department. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:179–84.

Grimholt TK, Jacobsen D, Haavet OR, et al. Effect of systematic follow-up by general practitioners after deliberate self-poisoning: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143934.

Grimholt T, Jacobsen D, Haavet O, et al. Structured follow-up by general practitioners after deliberate self-poisoning: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):245.

Scanlan JN, Hancock N, Honey A. Evaluation of a peer-delivered, transitional and post-discharge support program following psychiatric hospitalisation. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):307.

Cebria AI, Parra I, Pamias M, et al. Effectiveness of a telephone management programme for patients discharged from an emergency department after a suicide attempt: controlled study in a Spanish population. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1-3):269–76.

Normand D, Colin S, Gaboulaud V, et al. How to stay in touch with adolescents and young adults after a suicide attempt? Implementation of a 4-phones-calls procedure over 1 year after discharge from hospital, in a Parisian suburb. L'Encephale. 2018;44(4):301–7.

Hvid M, Vangborg K, Sorensen HJ, et al. Preventing repetition of attempted suicide--II. The Amager project, a randomized controlled trial. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(5):292–8.

Luxton DD, Thomas EK, Chipps J, et al. Caring letters for suicide prevention: implementation of a multi-site randomized clinical trial in the U.S. military and veteran affairs healthcare systems. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37(2):252–60.

Denchev P, Pearson JL, Allen MH, et al. Modeling the cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce suicide risk among hospital emergency department patients. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC). 2018;69(1):23–31.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This is a review article, so it did not require IRB approval or other requirements for human or animal studies. No consent was needed.

Conflict of Interest

There were no conflicts of interest.

Any Applicable Disclaimer Statements

No disclosures to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chaudhary, A.M.D., Memon, R.I., Dar, S.K. et al. Suicide during Transition of Care: a Review of Targeted Interventions. Psychiatr Q 91, 417–450 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09712-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09712-x