Abstract

There is limited data on how community medical providers in India attempt to diagnose and treat depression, as well as on their general knowledge of and attitudes toward depression. A cross-sectional survey was conducted assessing knowledge and views of clinical depression with 80 non-psychiatric physicians and physician trainees recruited from community clinics and hospitals in Gujarat, India. Interviews were also held with 29 of the physicians to assess what they do in their own practices in regards to detection of and treatment of clinical depression. Although subjects showed a generally good basic understanding of the definition of clinical depression and its treatment, their responses reflected the presence of some negative and/or stigmatized attitudes toward clinical depression. Our findings raise the question of possible stigma among physicians themselves and underscore the importance of combatting physicians’ stigma against and increasing awareness of how to detect and treat clinical depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clinical depression is an illness that affects more than 300 million people worldwide [1, 2] and is a leading cause of disability, with depressive disorders ranking as the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) as found in the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study [1]. Depressive disorders also account for worldwide disability and mortality by placing individuals at higher risk for physical illnesses such as ischemic heart disease and can have devastating consequences such as suicide.

India, the second most populous country in the world with a population of over 1.2 billion people [3], suffers from under-recognition and under-treatment of depression, the causes of which appear to be multifactorial. Stigmatizing attitudes towards depression are prevalent among Indians, which may prevent them from presenting to a medical professional and getting help [4]. Furthermore, the primary presenting complaints of depressed patients are most often somatic symptoms [5]. Indians have also been shown to less commonly think of depressive symptoms as being part of a mental disorder and are more likely to label their symptoms as “tension” or “worry” and view them as a product of psychosocial factors [6]. All these factors combine to make the detection of depression a challenge in the clinical setting.

It has been recommended by the World Health Organization that there be more widespread integration of mental health services into primary care as a means of increasing access to mental health care [7]. Given that there exists a shortage of mental health professionals in India [8], and that stigma may prevent patients from seeking help directly from mental health specialists, it is important that efforts be focused on improving recognition and treatment of depression in the primary care setting in India. In general, though most care for depression does take place in community medical settings worldwide, primary care practitioners have been shown to have high rates of missing diagnoses of depression in their patient populations [9, 10]. In Gujarat, India, one study held at a primary care clinic found that primary care physicians missed a diagnosis of clinical depression in over two-thirds of cases [11]. Thus far there has been limited data on how non-psychiatric medical providers in India attempt to detect and treat depression in their communities.

Related to this is the topic of Indian non-psychiatric physicians’ general knowledge of and attitudes toward depression, for which there is also limited research. There appears to historically be less emphasis on exposure to psychiatry during medical education in India. For instance, completion of a clinical rotation in psychiatry was only recently, in 2008, made a requirement for all medical students [12]. Furthermore, misperceptions of and stigma against mental illness are widespread in India, and extend even to a sample of community health workers and non clinically-practicing resident physicians as found in a previous study in Gujarat, India [13].

This study seeks to investigate these aforementioned areas by examining the knowledge about, attitudes toward, and treatment practices for depression in a sample of community physicians and physician trainees in and in the vicinity of Vadodara, a mid-sized city in the Indian state of Gujarat.

Methods

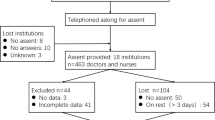

This study was conducted in January 2015 over a 4-week period undertaken as an elective for a global health psychiatry residency track, and was performed in collaboration with the MINDS Foundation, a non-profit organization aimed at expanding and delivering mental health care, support and education to patients with mental illness in rural India. With the aid of the local MINDS Foundation team, based in Vadodara, a sample of physicians was recruited from local roadside clinics in Vadodara and its vicinity, as well as from four hospitals in Vadodara. These four hospitals included Sumandeep Vidyapeeth University (SVU), which the MINDS Foundation carries an affiliation with, and Parul Sevashram Hospital (both privately owned teaching hospitals); and ESIC Hospital and Jamnabai Hospital (both government owned hospitals). Physicians included a mix of general practitioners (oftentimes known as medical officers- i.e. those who have a medical degree, M.B.B.S., but generally do not have a postgraduate degree such as a M.D. or M.S.), specialist physicians (who have pursued additional specialty training beyond basic undergraduate medical training, carrying a M.D. or M.S.) and resident physicians (physicians practicing and pursuing specialty training). Specialty fields represented included internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, cardiology, endocrinology, and chest medicine (pulmonology). In addition, a group of medical school interns, i.e., students in their final year of training, were also recruited from SVU. Interns were the only group of non-practicing physicians who participated in our study.

Using a 50-item questionnaire, we surveyed 80 participants about their knowledge and views on clinical depression. Physicians and interns were approached at their place of work and upon consent to the study, were given a copy of the survey to complete which was collected back either on the same day or at a later time. The survey used was the Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Depression (KATD) Survey which was used in the aforementioned study of community health workers and community medicine residents in Gujarat [13]. In addition to demographic questions (which were expanded from previous versions of KATD), there were 33 statements to which respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with 1 of 5 choices: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree. These items can be classified as each belonging to one of three categories: Knowledge of etiology of depression, perceptions of depression, and knowledge of treatment. In addition, a single open-ended question asked the following: What do you understand by the term “depression”? (Survey available upon request).

If the participant was a practicing physician, he or she was also asked to participate in an interview. This procedure was repeated until 26 interviews were performed with 29 practitioners, at which point it was felt that responses had reached sufficient saturation and no further new information was being elicited. Interviews were done predominantly as individual interviews, though in two instances they were done within a small group of two or three individuals due to convenience and/or time constraints.

For the interview, subjects were first asked to read a case vignette describing a woman experiencing symptoms of depression that met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Edition) [14] diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, a modified version of the one that was used to conduct focus groups from the same 2014 study of community health workers and community medicine residents by our lead investigator [13]. The vignette is included in Table 1. Physicians were then asked a series of questions that assessed their knowledge and understanding of what was occurring in the vignette, including questions on how they might approach such a patient if she presented to their practice. This provided a segue into a final few questions in which they were asked about what they do in their own practices to detect and treat clinical depression.

Both the surveys and interviews with the doctors were conducted in English, though a Gujarati-speaking social worker from the local MINDS Foundation team was present and available for occasional clarification or translation of questions.

Quantitative analysis was performed on the survey data. The mean and standard deviation were obtained for responses to each of the 33 KATD survey statements, where scores of 1 through 5 were given corresponding with 1 = “Strongly agree” through 5 = “Strongly disagree”. For each item, there existed a most “ideal” response, ideal meaning more indicative of increased knowledge of (from a Western perspective of clinical depression) and positive, non-stigmatized attitude towards clinical depression, which would be coded either as 1 or 5. “Ideal” scores for questions were reversed as needed for purposes of calculation of this score so that a higher score (i.e., 5) always reflects a more ideal score.

For each of these question items, the difference between the mean score and the “ideal” score was calculated. For purposes of this study, we defined a cutoff of a difference equal to or greater than 2 points as indicating a “less than ideal” response for that item. In addition, total KATD scores for each of the participants were calculated by taking the sum of their responses.

Qualitative analysis was performed on the single open-ended question in the survey (“What do you understand by the term depression?”), as well as on transcripts of the interviews, and performed according to the procedure previously used by our group [13]. Three investigators (D.L., N.M., and C.L.K.) separately coded the transcripts for salient themes. The three coding sets were then reviewed together to reach consensus themes.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of both Sumandeep Vidyapeeth University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Results

Survey

Demographics

Table 2 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the 80 participants for the survey portion of the study. Total KATD scores ranged from 97 to 141 points (the minimum possible number of points being 33 to the maximum possible number being 165) with a mean of 117.32 and standard deviation of 11.22. There were no gender differences found in total KATD scores. Age positively correlated with total KATD scores (r = .37, p < .01), and physicians’ scores are significantly higher than interns’ scores across (see Table 3), suggesting that increased years of clinical experience correlate with higher overall scores.

Comparison between Actual and “Ideal” Item Scores

Items in the survey for which there existed a mean difference of 2 points or more between the actual and “ideal” scores are listed in Table 4.

Knowledge of Etiology of Depression

Subjects’ responses to seven out of eight items assessing knowledge of the etiology of depression were consistent with the ideal answers. The one item for which responses were less than ideal was, “Do you think that depression is caused solely by unfavorable social circumstances?” The majority of respondents responded that they agreed with this statement, with only 2.5% of respondents to this question responding with “Strongly disagree.”

Perceptions of Depression

There were a total of five items (out of fifteen) where responses were less than ideal. For example, 41.2% of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement “Depression is a sign of weakness and sensibility” and 40% strongly agreed or agreed that “People who attempt suicide are weak”. Responses also indicated perceptions that depressed individuals were unpredictable or hard to talk to (i.e., increased affirmative responses to the statements “People with depression are hard to talk with” (41.3% strongly agreeing or agreeing) and “People with depression are unpredictable” (45% strongly agreeing or agreeing).)

Knowledge of Treatment

Subjects generally responded knowledgably about the ten items assessing awareness of the treatment of depression. The one item with less than ideal responses was, “Antidepressants will cause addiction” for which only 4 people strongly disagreed with this item and 30% strongly agreed or agreed with this item.

What Do You Understand by the Term “Depression”?

Narrative responses to this one open-ended question revealed a generally good awareness of depressive symptomatology (as per DSM-5 defined symptoms of depression) among respondents.

Interviews

Five broad themes emerged from the interview data:

-

1)

Depression as a result of social circumstances: There was an emphasis on the depressive presentation of the woman in the vignette being directly tied to her lack of support and resources. It was pointed out by some that women often faced unique stressors that could make them more vulnerable to depression- for example, difficult relationships with her in-laws or bearing a female child as opposed to a male one (the latter favored in traditional Indian culture).

-

2)

Predominance of physical complaints over emotional complaints: Interviewees almost universally agreed that physical complaints were the more common way by which patients present with clinical depression. Many stated that in the medical setting, diagnosis of psychiatric illness was often made by seeing multiple physical complaints without any physical findings. Furthermore, there appeared to be a common perception among interviewees that higher educated people were more likely to present directly to psychiatrist or be aware of psychological illness and poorer individuals and individuals from more rural areas were likelier to present somatically.

-

3)

Treating the patient through counseling first: Many physicians stated that counseling would be the first approach one would try in managing such a patient in the vignette, with some citing counseling as being more important than medication. There was widespread agreement that there is a lack of availability of professionals who specialize in counseling or psychotherapy, such as clinical psychologists or social workers. Many did not seem to have any familiarity with such referrals for psychotherapy. As a result, “counseling” would fall to either primary care doctors or psychiatrists. However, a large number cited time constraints of their day as being an obstacle to being able to provide counseling. At least three physicians mentioned that they would realistically be able to spare two or three minutes per visit to counsel the patient at most. Physicians also varied in their descriptions of the counseling they would provide for the patient in the vignette-- some suggested “reassuring words” and others stated they would give direct advice to the patient, such as instructing the patient to accept their adverse circumstances and to move forward with the daily tasks they need to accomplish.

-

4)

Varying levels of familiarity with and comfort with diagnosis and treatment of depression: Physicians were consistently able to identify the vignette as a case of clinical depression and agreed that organic causes would need to be ruled out before finalizing that diagnosis. However, there appeared to be very divergent comfort levels with diagnosing and treating, with some very confident and others just the opposite. There appeared to be a wide range of estimated cases of clinical depression encountered in the physicians’ practices, ranging from rare (2 cases in five years) to daily (1–2 cases a day). Finally, there appeared to be varying levels of comfort with prescribing psychiatric medications. Many stated that they do prescribe benzodiazepines and somewhat less frequently, an antidepressant, in their practices.

-

5)

Stigma as a barrier against psychiatric referral: While respondents almost universally agreed that referring such a clinically depressed patient in the vignette to a psychiatrist was an appropriate next step if they were not able to manage this patient’s depression on their own, many felt that patients would not be likely to go to the psychiatrist if referred. As one respondent stated, “If a man goes to a psychiatrist, he is a mad person.” Physicians stated they would likely encounter resistance from the patient and that the referral might even ruin the relationship between the patient and the physician- “It's very hard getting patients to see a psychiatrist. If you tell them to see a psychiatrist, they will stop coming and tell others not to see this doctor.”

Discussion

Overall, physicians and physician trainees, despite their generally limited exposure to psychiatry during medical training and real-world constraints in their practices (such as time) that might prevent them from more fully immersing into a role that allows them to become very familiar with psychiatric illness, appeared to demonstrate a good understanding of clinical depression and the basics of its treatment. Older, presumably more experienced and trained physicians appeared to have a better understanding compared to younger and presumably less experienced physicians as well as physicians still in their training. There were several survey items to which respondents tended to answer in a less “ideal” direction, the majority of which were pertaining to attitudes toward depression.

In both the quantitative and qualitative portions of our study, it was notable that physicians and physician trainees exhibited a tendency to perceive clinical depression as being a product of psychosocial circumstances, such as living in poverty or having difficulties with one’s family. This view of clinical depression is consistent with one that has been described to be common among Indians in general as opposed to Westerners-- that is, a decreased attribution of depression to a biomedical model and increased perceived role of psychosocial factors [6].

Our results also showed physicians finding an overwhelming predominance of somatic complaints, often in the form of vague or unexplained pains and aches over psychological complaints in the clinically depressed patient, which was unsurprising. Given how widespread this phenomenon is in India, it has been suggested that somatic idioms not only be considered in the diagnosis of depression among Indians, but even be used as the defining clinical features of the illness [5]. In fact, the presence of unexplained somatic complaints was effectively how physicians seemed to conclude likely diagnoses of clinical depression in their practices, though there was no indication of any standardized or systemic approach to doing this. Somatic presentations represent a diagnostic challenge as they have been linked to low recognition rates among primary care physicians [15]. Screening questionnaires can be a helpful addition to primary care practices, and while at least one mental health screening questionnaire that incorporates somatic symptoms has been developed for the Indian primary care setting, the Primary Care Psychiatry Questionnaire (PPQ) [16]), it may not be superior to more universally used screens that focus on psychological symptoms only [17]. This is an area that would benefit from further study.

It was notable that on the survey, a fairly large number of respondents agreed that antidepressants could cause addiction, which suggests a potential deficit in the understanding of psychiatric medications and their uses in clinical depression. It was unclear, however, whether this was the result of misunderstanding antidepressant medications themselves, or understanding of the term “antidepressant” to also include benzodiazepines, which are used adjunctively in the treatment of clinical depression and may lead to tolerance and other symptoms of addiction. Regardless, this finding suggests that non-psychiatric physicians may benefit from further education or training in this area, either at the undergraduate or continuing medical education level.

It is well known that there is a dearth of mental health professionals specializing in psychosocial interventions in India (WHO, 2005). Physicians in our study often suggested that they take on the role of counseling the patient in an effort to address their depression, though it is important to note that a rather simplistic understanding of the term “counseling” was common, with physicians’ responses suggesting that a patient’s depressed condition may improve after being given some reassuring words. At the same time, this small amount of “counseling” may also be understood as physicians trying to make some sort of intervention through talking or advice-giving, in the very limited amount of time that they can spend with patients. More research would be necessary to gain a better understanding of what, if any, basic psychosocial interventions naturalistically occur in Indian primary care and which could be most helpful in the primary care setting.

A major theme found in our results was the problem of stigma. In our interviews, physicians cited stigma experienced by patients as an obstacle in getting patients to acknowledge their depression and to accept appropriate treatment for it, the latter both in accepting pharmacological treatments for clinical depression and in getting referred to a mental health specialist. This is consistent with previous descriptions of frequent discontinuation of treatment and lack of adherence with medication [18], as well as prevalent stigma against being referred out to psychiatrists [19, 20] in India.

Given the obstacle that stigma presents in preventing Indians from gaining access to mental health care, it is concerning that negative perceptions of depression were found to not be uncommon among physicians and physician trainees themselves, as reflected by the large number of less than ideal responses on “Perceptions of Depression” on the survey. Similar results were also found in a recent study done of physician perceptions of mental illness in Hyderabad, India, in which 36.8% of a sample of physicians responded on a survey with negative attitudes towards clinical depression, with a large number of respondents perceiving depressed patients to be different and unpredictable, that they have themselves to blame, and must pull themselves together [21]. Interestingly, this observation is not limited to India; studies conducted across other countries have demonstrated similar patterns of health professionals displaying adequate knowledge about mental illness yet still having negative attitudes towards it, despite being trained in internationally accepted biopsychosocial approaches [22, 23].

Stigmatized attitudes, even if subtle, are problematic as they can adversely influence physicians’ own receptiveness towards diagnosing and treating depression in their patients. We observed that there did appear to be considerable variability among physicians’ comfort and real-world experience level with depressed patients, both via self-report and as was also suggested by a very wide range of estimates of numbers of depressed patients seen in their practices, with some physicians rarely detecting any depression at all in their practices. We may at least conjecture that it is easy to err on the side of ignoring or not putting large amounts of effort into detecting and treating depression in the medical setting, especially given patients’ inherent resistances towards the topic and also real world constraints, such as time. If true, this may perpetuate Indian patients’ resistance to receiving proper treatment for their mental health condition.

There were a number of limitations to our study. First, our reliance on a convenience sample potentially limits the generalizability of our results. Future research on a more representative sample is required to validate our findings’ applicability to medical practice in Gujarat and India.

Additionally, there is the possibility of language having been a potential barrier, given that surveys and interviews for this study were conducted in English and not the native language of these doctors, which is Gujarati. While subjects were generally all fluent in English (and it is the primary language used in medical education in India), it is possible that varying levels of comfort with English may have affected their comprehension of questions and terminology.

As this study was framed as one that assesses knowledge and attitudes on a topic that physicians may be expected to have some level of expertise or authority on, the subjects in this study may have responded to questions in a way that portrays themselves in a more favorable light, as possibly more knowledgeable and positive in attitude towards depression than how they might genuinely feel, especially in the interviews. However, if this indeed were the case, then our study would only have underestimated the extent of negative and/or stigmatized attitudes towards depression among Indian physicians.

Conclusions

Our study focused on assessing community medical providers’ knowledge of and attitudes toward clinical depression, as well as on understanding more about what occurs in the medical setting in India regarding evaluating or treating patients who present with symptoms of depression. In regards to their approach to diagnosing depression in the medical setting, physicians usually did not elicit psychological complaints but more commonly would encounter vague, unexplained somatic symptoms leading them to this possible diagnosis. Overall, while providers performed fairly knowledgably on the survey, responses indicated that stigma may be a large barrier that may hinder both patients and providers from obtaining and providing proper treatment. Lack of resources in the outpatient medical setting, including large workloads and limited time to spend with patients, also contribute to less-than-optimal care for depression in such settings. Given the importance of primary care providers and other non-psychiatric medical providers in serving as a conduit for depressed patients to get care, it is important that emphasis be placed not simply on the education of Indian physicians’ knowledge of detection and treatment of depression, but also on combatting stigma. This should ideally occur both at the level of undergraduate training and at the continuing medical education level.

References

Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJ, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547.

World Health Organization. Depression Fact sheet N°369. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Accessed 30 June2017.

CIA, The World Factbook- India. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/in.html Accessed 30 June 2017.

Nieuwsma JA, Pepper CM, Maack DJ, Birgenheir DG. Indigenous perspectives on depression in rural regions of India and the United States. Transcult Psychiatry. 2011;48(5):539–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461511419274.

Pereira B, Andrew G, Pednekar S, Pai R, Pelto P, Patel V. The explanatory models of depression in low income countries: listening to women in India. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1–3):209–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.025.

Andrew G, Cohen A, Salgaonkar S, Patel V. The explanatory models of depression and anxiety in primary care: a qualitative study from India. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:499. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-499.

World Heath Organization and World Organization of Family Doctors (Wonca). Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. 2008. http://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/mentalhealth_PHC_2008.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2016.

World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas. Geneva. 2005. http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles_countries_e_i.pdf?ua=1. Accessed March 8, 2016.

Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):609–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60879-5.

Wittchen HU, Hofler M, Meister W. Prevalence and recognition of depressive syndromes in German primary care settings: poorly recognized and treated? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(3):121–35.

Amin G, Shah S, Vankar GK. The prevelance and recognition of depression in primary care. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40(4):364–9.

Thirunavukarasu M, Thirunavukarasu P. Training and national deficit of psychiatrists in India - a critical analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S83–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.69218.

Almanzar S, Shah N, Vithalani S, Shah S, Squires J, Appasani R, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes toward clinical depression among health providers in Gujarat. India Ann Glob Health. 2014;80(2):89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.001.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Assocation; 2013.

Paykel ES, Priest RG. Recognition and management of depression in general practice: consensus statement. BMJ. 1992;305(6863):1198–202.

Srinivasan TN, Suresh TR. Non-specific symptoms and screening of non-psychotic morbidity in primary care. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32(1):77–82.

Patel V, Pereira J, Mann AH. Somatic and psychological models of common mental disorder in primary care in India. Psychol Med. 1998;28(1):135–43.

Pradeep J, Isaacs A, Shanbag D, Selvan S, Srinivasan K. Enhanced care by community health workers in improving treatment adherence to antidepressant medication in rural women with major depression. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139(2):236–45.

Chadda RK, Shome S. Psychiatric aspects of clinical practice in general hospitals: a survey of non-psychiatric clinicians. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:86–91.

Chaudhary RK, Mishra BP. Knowledge and practices of general practitioners regarding psychiatric problems. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18(1):22–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.57853.

Challapallisri V, Dempster LV. Attitude of doctors towards mentally ill in Hyderabad, India: results of a prospective survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57(2):190–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.158190.

Aydin N, Yigit A, Inandi T, Kirpinar I. Attitudes of hospital staff toward mentally ill patients in a teaching hospital. Turkey Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2003;49(1):17–26.

Stefanovics E, He H, Ofori-Atta A, Cavalcanti MT, Neto HR, Makanjuola V, et al. Cross-National Analysis of beliefs and attitude toward mental illness among medical professionals from five countries. Psychiatry Q. 2016;87(1):63–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9363-5.

Funding

This study was funded by The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Daniella A. Loh declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Amul Joshi declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Kanako Taku declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Nathaniel Mendelsohn declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Craig L. Katz declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Loh, D.A., Joshi, A., Taku, K. et al. Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Clinical Depression among Community Medical Providers in Gujarat, India. Psychiatr Q 89, 249–259 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9530-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9530-y