Abstract

We report on a partnership between the NYS Department of Health and Office of Mental Health that delivered the full integration of depression care into primary medical care. Called the NYS Collaborative Care Initiative (NYS-CCI), nineteen NYS academic medical centers participated. Based on principles of chronic illness care, Collaborative Care detects and manages depression in primary care using a highly prescriptive protocol (University of Washington AIMS Center website: http://uwaims.org/). Fidelity was ensured by measuring screening rates, diagnosis, enrollment, and improvement among those in treatment for 16 weeks. There was significant, progressive performance improvement in sites that served over 1 million patients over the course of the two and a half year grant. Clinics also reported satisfaction with the CC model. Based on the experience gained, we recommend a number of critical actions necessary for the successful implementation and scaling-up of CC throughout any state undertaking this endeavor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Behavioral health disorders, such as depression, are among the most prevalent health conditions in New York State and throughout the country, disabling many and impairing successful control of or recovery from co-existing medical disorders, including diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular and lung diseases, cancer, and neurological illnesses. Although safe and effective treatments for depression exist, the great majority of people in need are not being detected or receiving adequate care due to: how they are managed (not managed, in effect) in primary care; access problems to specialty mental health care: a shortage of mental health specialists; and stigma [1].

As health care systems undergo transformation, care is becoming more consumer-centered and measures are being put in place to drive down overall costs [2]. In this health care environment, there is increasing recognition of the vital role of “integrated care” programs, and commitment to providing them (Appendix 6). Integrated care aims to provide both medical and mental health care in one setting, most often within primary care. Accessibility to depression treatment in primary care is convenient for consumers, can help to reduce the stigma associated with the treatment for mental disorders, builds upon existing doctor–patient relationships, improves care and outcomes for patients who have both depression and co-occurring medical disorders, and over time can reduce costs. Evidence also shows that patient satisfaction with integrated care systems is high [3, 4].

Collaborative Care (CC), as we use the term here, refers to an evidence-based model for delivering quality depression care in a primary care setting. Developed at the University of Washington and based on principles of chronic illness management, CC focuses on detecting depression in primary care using a specific validated screening test, then medical diagnosis of the disorder, followed by tracking those with the illness through a registry, with the use of a measurement-based depression care path that identifies needed changes in treatment if a patient does not improve; in addition, there is training of clinical and administrative staff in the practice, and educating and activating patients.Footnote 1 Collaborative Care has now been tested in more than 70 randomized controlled trials in the USA and in other countries, in a variety of treatment settings, in both urban and rural environments and with diverse patient groups (Appendix 1) [1].

Evidence suggests that collaborative care for depression not only improves consumer outcomes for depression but also for common co-occurring general medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia [5]. It has been shown to lead to better patient and provider satisfaction. In addition, CC has demonstrated cost savings in long-term studies when compared to conventional care [6].

Despite its robust evidence base, large scale implementation of CC has been very limited. This is largely because CC requires practice changes on multiple levels—it is tantamount to a new way of practicing medicine. However, with this amount of evidence of its effectiveness, with improved patient and provider satisfaction, and with the need to reduce unnecessary spending, its adoption has been increasing and needs to scale-up further.

The New York State Collaborative Care Initiative (NYS-CCI)

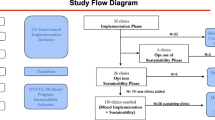

New York State has committed its medical policy and practice goals in integrating behavioral (mental) health care into primary care. In what may be the largest state government behavioral health effort, through the New York State (NYS) Hospital Medical Home Program, the NYS Department of Health (DOH) and Office of Mental Health (OMH) have partnered to implement CC for depression across the state [7]. The NYS Collaborative Care Initiative (CCI) for depression has been part of a 2.5 year, Federal Hospital-Medical Home (HMH), Graduate Medical Education (GME) grant-funded project designed to advance primary care practices, including the integration of mental health, throughout New York State. The NYS-CCI is specifically the integration of depression care into ambulatory, primary care resident training sites, using selected Academic Medical Centers (AMCs). This project began in July of 2012 and ended in December 2014 when the grant terminated.

As the largest state sponsored implementation of integration of behavioral health in primary care to date, questions as to whether CCI implementation is feasible, successful, scalable and sustainable in NYS (and across the country) are critical clinical and policy questions that call for answers. We report on our experience and lessons learned here.

What are the Essential Elements of CC?

CC in a primary care setting has explicit requirements for what constitutes a clinical team and the essential elements of care that must be provided (Appendix 3). CC is delivered by a depression care team. This team approach includes: (1) training primary care providers in screening for and treating common mental health conditions, in this case depression; (2) employing in the primary care setting care managers who engage, educate, and provide basic counseling and medication support for patients diagnosed with depression and entered into the registry and treated; and, (3) psychiatrists who provide caseload consultation as well as consult on those patients who may need changes in treatment or more intensive, specialty services to care managers and primary care physicians, principally by telephone or video.

The CC approach also requires a very particular set of tools: a standardized screen for depression [the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)] [8] (Appendix 7) to detect and track the progress of depressed patients using a registry (similar to diabetes and asthma registries) (see footnote 1). The monitoring and tracking allows primary care doctors and care managers to adjust and/or intensify treatment if clinical improvements are not achieved as expected, much as tracking a person’s hypertension would lead to changes in treatment. Referrals to specialty mental health care are typically also reduced as effective care is delivered in the primary care setting, thereby sparing specialty mental health resources for those with the most significant mental health conditions.

The NYS CCI Project: Implementation

OMH contracted with the AIMS center at the University of Washington to provide the technical assistance needed by participating clinics to implement CC through the HMH project. The AIMS center subcontracted with the Institute for Family Health (IFH) to provide training and technical assistance in NYS. A core team developed the training program specific for the New York state sites. In all, 19 academic hospital centers across NYS chose to implement CC at one or more of their primary care clinics (32 clinics serving 1 million patients).

The technical assistance was designed to be delivered in two tracks: “Innovator” and “PCMH grantee” sites. Six medical centers were chosen as innovator sites and received intensive training and technical assistance, including in-person workshops, webinars, and regular ongoing consultation. The other sites, the PCMH grantees, received webinars and information packages on implementation. This distinction fell away over time as many sites engaged their own technical assistance in addition to what this project provided.

All sites began seeing patients by the requirements of the grant by July 2013. They reported quarterly on the project deliverables (specified in Appendix 2). The project deliverables were established to help ensure fidelity to the core aspects of the CC model and thus its likely success (Appendix 4).

The NYS CCI Project: Results

Nineteen Academic Medical Centers implemented CC in 32 of their primary care clinics. Over time, all clinics worked to improve their implementation of CC based on continuous information feedback and technical assistance; data collected during the project (by DOH) indicate almost all practices succeeded in delivering CC.

In general, with the exception of screening yield among those screened, which was relatively stable around 10–13 %, all other measures, including rates of screening, depression diagnosis given positive screens, enrollment in depression care given positive depression diagnosis, and improvement among those in treatment for 16+ weeks showed improvement over the course of the grant (Fig. 1).

At the beginning of the implementation, many clinics reported they had some form of depression screening protocol in place; however, in fact, on average across clinic less than half (46 %) of patients served were screened for depression at the beginning of the grant. Over the 2 years of the project, participating clinics steadily increased their screening rate, with an end of grant average screening rate across clinics of 85 %, with many clinics near 100 %. Of the 32 clinics, 23 (72 %) met or exceeded the original goal of screening 85 % of all patients screened at least annually. Training and new practice protocols were put into place to ensure that depression screening became standard practice, much like measuring blood pressure or HgA1c (Table 1).

The number of patients with a positive screen who were then diagnosed with depression also increased over the course of the grant, indicating that fewer patients with this illness were falling through the cracks. We saw evidence of better follow-up on positive screens and, with training, PCPs becoming more comfortable making a diagnosis of depression and treating the condition in their practices. The rate of diagnosis of depression among those with a positive screen increased from an initial rate of 44 to 66 % by the end of the grant, on average across clinics.

In terms of enrollment, the number of those diagnosed with depression who were subsequently enrolled in CC has increased from a low of 32 to 43 %. This has in part been due to increased staffing (especially of care managers), the use of Electronic Health Record fields or spreadsheets to enroll patients in CC, and the enthusiasm that comes from experiencing success in implementing an effective treatment that patients like. During the final quarter of the project, nearly 6000 patients were enrolled in CC, a threefold increase from the previous year, suggesting that as clinics become familiar with the model they can improve their patient engagement and retention in care.

Finally, CC was effective in reducing the burden of depression among a large proportion of those retained in treatment. At the end of the grant (Q7–Q8), 45–46 % of patients in treatment for at least 16 weeks showed improvement of their PHQ-9 scores to less than 10 up from only 17 % at the end of the first year (Q4); this is indicative of significant clinical improvement as scores <10 are generally not consistent with a diagnosis of clinical depression.

Provider and Consumer Experience

The participating clinics reported increased satisfaction with their implementation and the use of this model. Primary Care providers (PCPs) remarked that it is a pragmatic approach, appreciate the psychosocial support for their patients, and wish to see it sustained in their clinics. Anecdotal feedback from consumers was also very positive (Appendix 5).

One patient, who had a PHQ-9 that went from 16 (moderate depression) to 6 over the course of 5 weeks, was a 55 year old man with many chronic medical conditions who had recently moved to NYC and had little support. His treatment included sessions of problem solving therapy, which helped him organize his scheduling and time. His attention to his medical illnesses also improved as he became an active participant in his own self-care.

Another success story is that of a 58 year old patient who originally had a PHQ-9 score of 19 (moderate to severe). She had a history of recurrent major depressive disorder. Through her participation in a program of self-care as well as receiving better medication dosing and care manager support she was able to reduce her PHQ-9 score to 9, as well as cut her smoking down to half within a few weeks. She reported new found optimism for her future.

Across the sites, both clinicians and patients commonly reported enthusiasm about delivering CC.

Because the fully realized adoption of CC was at most 1½ years, less in most sites, we did not attempt to determine if medical costs were reduced in the population receiving CC. Ongoing work, supported by a Medicaid supplemental payment, will attempt to do so.

Lessons Learned and Barriers to Sustainability

Overall, there was considerable performance improvement by primary care practices, over 2 years, in the implementation of CC. With the right training and support, CC is both feasible and effective. In fact, we anticipate the results to date to increase over time, as long term studies of the CC model show that gains accrue—especially in years 3 and 4, both in terms of cost effectiveness and reduced medical morbidity among patients with co-existing depression.

However, there have been challenges to the large sale implementation of CC in NYS. Trying to change the attitudes of physicians and creating a radical shift in the way medicine is practiced often initially prompts many clinicians (and administrators) to resist. Primary care physicians have traditionally been reluctant to treat depression in primary care, and psychiatrists have been reluctant to manage care through a caseload model of consultation (without face to face evaluation). Integration, thus to date, has not been a standard of primary care practice. Because Collaborative Care is a fundamental departure from usual care, it requires practitioners to orient to the model and learn new roles—an often underappreciated aspect of implementing Collaborative Care.

Another challenge was that there have been other demands on practices related to other aspects of health care transformation, leaving many providers overwhelmed by new practice demands, the introduction of additional regulatory and payment requirements, and almost constant change. However, as clinics adapted to the model (with ongoing technical assistance) we received positive feedback that as primary care physicians and practices felt supported they became able to detect and treat depression in patients whom they had known to be ill for years but had never screened or diagnosed.

A second and substantial challenge involved the way the project was funded. Funding was provided centrally to the AMCs, not to the actual primary care practices; some, as a result, encountered barriers to receiving the money they needed from their central offices to implement the model properly. Many AMCs were initially reluctant to hire the additional staff required for such a model, concerned about the end of the funding period and how they would pay for such staff or bill for the new care methods required whose expenditures had been covered by the grant. Many sites reported hiring freezes or significant delays in obtaining approval to hire additional staff with no clear, future funding stream to support staff time.

A third challenge was that practices seemed reluctant to fully invest in the training and quality improvement of a model that itself came with a variety of regulatory and licensing burdens. Along with insecure funding, regulatory barriers added to the reluctance of practices to fully commit to implementation of a model whose sustainability remained uncertain.

Another challenge worth noting is the difficulty in obtaining standardized performance reporting. Even well operationalized metrics may not be reported in the same fashion across providers without built in quality checks. Given the large number of practice transformation projects typically underway in primary care practices today, provider capacity to respond to multiple third party quality improvement data requests is limited.

Recommendations

The following are recommendations to sustain CC based on the experience of the CCI in NYS.

-

1.

There must be a clear and credible path to state level payment mechanism(s) beyond grant funding.

-

2.

Clinics must be able to implement CC without undue regulatory and licensing burdens; for example, meeting both the requirements of the departments of health and mental health.

-

3.

There needs to be continued support for training and supervision in integrated care and attention to recruiting and retaining the staff needed to deliver CC, including the hiring and supervision of care managers and the presence of psychiatrists needed for consultation in collaborative care.

This is a remarkable time in health and mental health transformation—perhaps the greatest changes we have seen in the country since the 1960s. We are seeing an historic push toward truly integrated care. We believe the NYS-CCI project offers experience, knowledge, and hope to propel health care systems forward in delivering integrated mental health care. What we have achieved can be scaled-up further in NYS, and throughout this country.

Notes

University of Washington AIMS Center website: http://uwaims.org/.

A Psychiatric Consultant supports the PCP and Care Manager in treating patients with behavioral health problems. He/she typically meets with the Care Manager weekly to review the treatment plan for patients who are new or who are not improving as expected. Between 75 and 90 % of patients are typically reviewed in this way. This kind of case review counts as a psychiatric consultation for this metric. The Psychiatric Consultant may also suggest treatment modification for the PCP to consider. This counts as a psychiatric consultation for this metric. In addition, the Psychiatric Consultant can see the patient directly. This counts as a psychiatric consultation for this metric. The numerator in this metric is meant to encompass the number of patients for which any of these 3 types of psychiatric consultation occurred.

References

Unutzer J, Harbin H, Schoenbaum M, Druss B: Canter for Health Care Strategies and Mathematical Policy research for Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Collaborative care model: an approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. http://www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf.

Sederer LI: What does it take for primary care practices to truly deliver behavioral health care? JAMA Psychiatry 71(5):485–486, 2014.

Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al.: Community Preventive Services Task Force: Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 42(5): 525–538, 2012.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J et al. Collaborative care for depression: A cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine 166:2314–2321, 2006.

Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M et al.: Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. New England Journal of Medicine 363:2611–2620, 2010.

Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY et al. Long term cost effects of collaborative care for late life depression. American Journal of Managed Care 14(2):95–100, 2008.

Hospital-Medical Home (H-MH) Demonstration. New York State Department of Health website. https://hospitalmedicalhome.ipro.org/.

Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Annals of Family Medicine 8(4):348–353, 2010.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Research Bibliography

Appendix 2: DOH-HMH Quarterly Reporting Metrics

See the following link for full metrics description and FAQ, http://uwaims.org/nyscci/files/MetricsSummary_FAQ.pdf.

Depression Screening: DOH-HMH

Numerator definition: Number of unique adult patients per calendar year from the outpatient site who received a PHQ-2 or a PHQ-9. This should be the number of patients with at least one screening. Patients should not be counted twice for this metric, even if they come in more than once in the year or are screened more than once in the year.

Denominator definition: All patients from the outpatient site. This should be the number of unique adult patients from the outpatient site who have had a visit within the calendar year. Patients should not be counted twice, even if they come in more than once in the year.

Enrolled Patients with Psychiatric Consult: DOH-HMH

Numerator definition: Number of unique adult patients enrolled in the Collaborative Care Initiative for which a psychiatric consultationFootnote 2 occurred this reporting period.

Denominator definition: All patients enrolled in the Collaborative Care Initiative this reporting period. This means any patient who is currently enrolled at the time of reporting.

Patients Diagnosed with Depression: DOH-HMH

Numerator definition: Number of unique adult patients screened positive from the outpatient site who were then diagnosed with depression (eliminates false positives on screen). The numerator should be the number of unique patients screened positive for depression who were also clinically diagnosed with depression during the reporting period.

Denominator definition: All patients from the outpatient site screened positive for depression. The denominator should be the number of unique patients screened positive for depression during the reporting period.

Patients Enrolled in a Physical-Behavioral Health Program: DOH-HMH

Numerator definition: Number of unique adult patients per year from the outpatient site screening positive for depression who enrolled in physical-behavioral health care coordination program (Collaborative Care Initiative). The numerator should be the cumulative number of unique patients enrolled in the program for the year.

Denominator definition: All patients from the outpatient site screened positive for depression per year. The denominator should be the cumulative number of unique patients who screened positive for depression during the year.

Patients should not be counted twice for this metric, even if they come in more than once during the year or are screened more than once during the year.

PHQ-9 Decreases Below 10 in 16 Weeks or Greater: DOH-HMH

Numerator definition: Number of unique adult patients enrolled in the Collaborative Care Initiative whose PHQ-9 went from at >10 to <10 in 16 weeks or greater.

Denominator definition: All patients enrolled in the Collaborative Care Initiative who have been in the program over 16 weeks.

Receiving Meds/Therapy after Six Months: DOH-HMH

Numerator definition: Number of unique adult patients enrolled in the Collaborative Care Initiative still receiving medication and/or psychotherapy six (6) months after enrollment. This is the number of patients still receiving depression treatment 6 months after enrollment.

Denominator definition: All patients currently enrolled in the Collaborative Care Initiative.

Monthly Progress Report Metrics

Depression Screening: Monthly Progress Report

Numerator definition: Number of unique patients seen over the reporting month who have been screened over the last year.

Denominator definition: Number of unique patients seen over the reporting month.

Patients Enrolled in a Physical-Behavioral Health Program: Monthly Progress Report

Numerator definition: Number of unique adult patients from the outpatient site screening positive for and diagnosed with depression that enrolled in the physical-behavioral health care coordination program (Collaborative Care Initiative) this reporting month. For example, for the reporting period of April 2014, in the numerator include only the number of unique patients who screened positive for and were enrolled in the care program.

Denominator definition: All unique patients from the outpatient site screened positive for and diagnosed with depression this reporting month. For example, for the reporting period of April 2014, in the denominator include only the number of unique patients who screened positive for and were diagnosed with depression in April 2014.

Retention: Monthly Progress Report

Numerator definition: Current number of unique adult patients from the outpatient site who have been enrolled in the physical-behavioral health care coordination program (Collaborative Care Initiative) for at least 12 weeks, with administrative evidence of at least three clinical contacts during the 12 weeks, at least 1 of which was in person. This means sites will need to make sure they start tracking number and type of contacts in April to be able to report on this metric accurately.

Denominator definition: Current number of unique adult patients from the outpatient site: enrolled in the physical-behavioral health care coordination program (Collaborative Care Initiative) regardless of how long they have been enrolled or the number of clinical contacts they have had.

Appendix 3: CC Essential Elements

Appendix 4: Principles of Effective Integrated Care

Appendix 5: PCPs and Collaborative Care

Appendix 6: Usual Care Versus Collaborative Care

Appendix 7: Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): 9 and Scoring

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sederer, L.I., Derman, M., Carruthers, J. et al. The New York State Collaborative Care Initiative: 2012–2014. Psychiatr Q 87, 1–23 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9375-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9375-1