Abstracts

This study sought to identify profiles associated with substance dependence only, mental disorders only and co-occurring disorder respectively, using a broad range of socio-demographic, socio-economic, health beliefs, clinical and health services utilization variables concurrently. Based on a broad analytic framework, 423 participants diagnosed with substance dependence only, mental disorders only or co-occurring disorders within a 12-months period were studied. The study used comparison analysis, and a multinomial logistic regression model. Participants with dependence only and mental disorders only were in contrast in terms of gender, age, marital status, self-perception of physical health, perception of the physical conditions of their neighbourhood, impulsiveness, psychological distress and visit with a family physician in previous 12-months, while those with co-occurring disorders were in an intermediary position between the other two groups. Public authorities should especially promote strategies that could increase the capacity of family physicians to take care of individuals with substance dependence only.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey– Mental Health (CCHS- MH), 10.1 % of the Canadian population has had a mental or a substance use disorder within a 12-month period [1]. While in the majority of these cases, mental and substance use disorders have occurred separately, epidemiological studies confirm that these types of disorders do often co-occur [2]. According to a recent review of epidemiological studies [3], 7–45 % of individuals with an alcohol dependence, and 17–55 % with a drug dependence have also had a mood or anxiety disorder [4].

A number of studies have shed light on variables associated with substance dependence, mental disorders or co-occurring disorders. The prevalence of substance dependence is higher among males and younger adults [5]. Other variables associated with substance dependence include singlehood, living alone, lack of social support, impulsiveness and psychological distress [6–8]. Main variables associated with mental disorders are female gender, youth, singlehood, poverty and lack of social support [9–12]. Main variables associated with co-occurring disorders are youth, female gender, poor education, psychological distress and homelessness [13–19].

Others studies have investigated patterns of services utilization among individuals with mental disorders, substance dependence or co-occurring disorders [13, 20–29]. Some of those studies looked at patterns of service utilization of individuals with substance dependence, common mental disorders, and co-occurring disorders among a general population [23–25, 28]. Those studies found that individuals with substance dependence use significantly less health services than individuals with co-occurring disorders or mental disorders. To our knowledge, only one study [18] compared profiles of people having only a substance use disorder, only a mental disorder and co-occurring disorders using concurrently variables such as socio-demographics, socio-economics, health beliefs, clinical and health services utilization. However, the study aimed to compare variables associated with perceived unmet needs among individuals with co-occurring disorders with those having only a substance use or a mental disorder.

Based on a broad analytic framework, this study sought to identify profiles associated with substance dependence only, mental disorders only, and co-occurring disorders respectively in a catchment area survey, using comparison analysis and a multinomial logistic regression model.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The study focused on an epidemiological catchment area in Montreal, Canada’s second-largest city. The catchment area includes 269,720 citizens living in four neighbourhoods. The proportion of low-income households is 33 versus 23 % in the province of Quebec. Healthcare services are delivered mainly by three organizations: two health and social service centers offering primary and specialized healthcare and a psychiatric hospital delivering specialized care. Mental healthcare services in the area are also provided by about 40 medical clinics, a similar number of private psychologists, and 16 community-based agencies, all of which deliver primary care. Addiction services are mainly provided outside the catchment area. The Montreal area comprises two public addiction rehabilitation centres offering specialized care (one each for the French and English communities), along with numerous self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, providing first-line services and support. However, there are remarkably few specialized services for co-occurring disorders in the area—as is typically the case everywhere else in the world [30].

Selection Criteria and Study Sampling

To be included in the survey, participants had to be aged between 15 and 65 and reside in the catchment area. For those aged under 18, parental consent was required before the interview. A single participant per household was selected using procedures and criteria from the National Population Health Survey (2003–2005). The sampling was equally distributed among the various neighbourhoods in the study area. Data was collected randomly from June to December 2009 by specially trained interviewers. The research was approved by relevant ethics boards.

A randomly selected sample of 2,434 participants took part in the survey. The response rate (49 %) was superior to the median rates reported in epidemiologic studies of populations since the 2000s, which coincided with a steady decline in participation rates over the past 30 years [31, 32]. There was an overrepresentation of females (62 %) in the final study sample compared to the reference population (52 %); men under the age of 45 were underrepresented. Data for sex and age were weighted so as to achieve the correct prediction of prevalence of mental disorders in the population.

Variables Used for Analyses and Measurement Instruments

Variables used for analyses were displayed in Fig. 1. They were grouped in five categories (socio-demographic, socio-economic, health beliefs, clinical and health service utilization variables) in accordance with a conceptual framework based on previous models and especially on Caron’ Satisfaction with quality of life framework [33], and the Andersen’s behavioral model of health services utilization [34]. Variables were chosen in view to take into consideration all dimensions that could be significantly associated with substance dependence, mental disorders and/or co-occurring disorders according to the literature.

Mental health diagnostics were based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), an instrument created by a Word Health Organization working group [35]. CIDI diagnoses, based on the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), included anxiety disorders (i.e. agoraphobia, social phobia, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder), and mood disorders (major depression, mania). Substance disorders (alcohol and drugs) were based on the CIDI-short form (CIDI-SF) [36]. Socio-demographic and economic data were collected using the CCHS 1.2 [37]. Psychological distress was rated using the ten-question Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [38]. Impulsiveness was evaluated with the Barratt Impulsivity Scale [39]. Social support was measured with the Social Provisions Scale [40]. Quality of life scores were determined with the Satisfaction with Life Domains Scale [41]. Self-reported aggressive behaviour was assessed using the Modified Overt Aggression Scale [82]. The physical state of neighbourhoods was evaluated using the Physical Conditions of the Neighbourhood scale [43]. Measurement instruments are described more in details in Table 1.

Analyses

Analyses encompassed univariate, bivariate and multivariate statistics. Univariate statistics comprised frequency distributions for categorical variables and mean values along with standard deviations for continuous variables. Bivariate analyses encompassed (1) comparative analyses (using Pearson’s Chi square or Fisher’s exact test) between the three groups of participants with substance dependence, mental disorders, and co-occurring disorders; and (2) logistic regression analyses using Chi squared statistics between independent variables and the multi-categorical dependent variable: “having substance dependence exclusively or mental disorders exclusively or both combined in prior 12-months,” with the Alpha value set at P < 0.10. Variables that yielded significant association in bivariate analyses were introduced in the multinomial logistic regression model via the backward deletion technique (Alpha value set at P < 0.05). The proportion of variance explained (Nagelkerke R2) was calculated.

Results

Among the 2,434 participants who took part in the survey, 423 (17.4 %) had experienced mental disorders only (n = 280; or 11.5 % of the total sample), substance dependence only (n = 87; or 3.6 %), or co-occurring disorders (n = 56; 2.3 %) in the 12-months before the interview and were selected for subsequent analyses.

Compared to participants with co-occurring disorders, those with substance dependence only were more likely to be male (socio-demographic variable), and to have a higher quality of life (socio-economic variable) They were also more likely to perceive positively their physical health and their mental health, to be satisfied or very satisfied with life (health beliefs variables) and to have a lower level of psychological distress and impulsiveness (clinical variables). Finally, they were also less likely to seek the services of a family physician, psychiatrist or psychologist (service utilization variables) and, marginally, to consult to family physicians often and to use self-help or support groups (Tables 2, 3). Compared to participants with mental disorders only, those with substance dependence only were more likely to be single, male, younger, (socio-demographic variables), to have a higher quality of life, and to have a bad perception of the physical conditions of their neighbourhood (socio-economic variables). They were also more likely to be satisfied or very satisfied with life, to perceive positively their physical health and their mental health, and to view spirituality as not important (health beliefs variables), and to have a lower level of psychological distress and a higher level of impulsiveness (clinical variables). Moreover, they were significantly less likely to call on a family physician, an addiction counsellor, a psychiatrist or—marginally—other professionals, but were more likely to use self-help or support groups (service utilization variables). They were also less likely to regularly see a family physician and, marginally, to visit with a high number of professionals (service utilization variables). Finally, as compared with participants with mental disorders only, those with co-occurring disorders were more likely to be single, male, younger (socio-economic variables) and to have a lower quality of life, and a negative perception of the physical conditions of their neighbourhood (socio-economic variables). They were also more likely to be dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with life (health beliefs variables), to have a higher level of psychological distress and impulsiveness (clinical variables), and to consult a psychologist or an addiction counselor and to use self-help groups (service utilization variables).

Variables used to build the multinomial logistic regression model appear at the bottom of Table 4. The model yielded eight variables significantly associated with “having substance dependence only, mental disorders only or co-occurring disorders.” Compared to participants with substance dependence only, which was the reference group, those with mental disorders only were more likely to be female, older and living in couple, to have higher levels of psychological distress, lower impulsiveness, poor self-perception of physical health, to have good perception of the physical conditions of their neighbourhood, and to have visited a family physician in previous 12-months. Likewise, compared to participants with substance dependence, those with co-occurring disorders were more likely to be female, to have higher levels of psychological distress and poor self-perception of physical health and to have visited a family physician in previous 12 months. In both cases, having visited a family physician in previous 12-months was the most influential association. This model explains 45 % of the total variance.

Discussion

In this study, the twelve-month prevalence of substance dependence and mental health disorders both with co-occurring disorders was respectively 5.9 and 13.8 % versus 3 and 8.4 % in Canada in 2002 according to the CCHS 1.2 [4]. Moreover, the prevalence of co-occurring disorders was 2.3 % in this study versus 1.7 % in Canada according to the CCHS 1.2 [4]. The high proportion of low-income households in the catchment area could explain why the results differed from those presented by Rush et al. [4]. According to the literature, prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders are higher in low-income populations [44]. The presence of a psychiatric hospital in the catchment area may also explain both the higher prevalence of substance dependence, mental disorders and co-occurring disorders in the sample. It is possible that some of the participants were affected by a mental disorder not measured in the study, such as personality disorders or schizophrenia, which could explain why they seek more often professionals for mental-health reasons. Usually, individuals with a severe mental disorder tend to live near their treatment center.

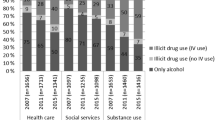

Furthermore, all three groups in this study were more frequent users of services of family physicians, psychiatrists and psychologists, compared to findings of previous studies [19, 23, 25]. In 2002, for example, the proportions of Canadians seeking the advice of a family physician, a psychiatrist and a psychologist within a 12-month period were respectively 6.2, 1.8 and 2.3 % among individuals with substance dependence; 31.6, 14.1 and 10.0 % among those with mental disorders; and 34.6, 16.1 and 11.0 % among those with co-occurring disorders [19]. In this study, the proportions were 9.3, 7.0 and 11.6 % respectively among participants with substance dependence; 35.8, 17.0 %, and 17.0 % among those with mental disorders; and 37.5, 25.0 and 29.2 % among those with co-occurring disorders. A previous paper with the same sample revealed that 52 % of the individual who had a mental disorder in a 12-month period, with or without co-occurring substance dependence, used healthcare services for mental health reasons [45]. Among those formers, the same proportion used both primary care and specialized services [45]. The presence of the psychiatric hospital as well as the important number of professionals and resources offering primary care services in the area could explain this greater health service utilization for mental health reasons. In addition, the over utilization of psychologists could be explained by the high ratio of psychologists in Quebec, which is twice the Canadian average [46]. Psychologists are the top group of professionals consulted for mental-health reasons in Quebec after family physicians while, elsewhere in Canada, they rank only fourth [47].

The multinomial logistic regression model showed that participants with mental disorders only and those with substance dependence only differed on all the variables included. As regards socio-demographic variables, differences were found in gender, marital status and age, which is conform with to results of previous studies [12, 18, 48]. Concerning gender, the incidence of anxiety and mood disorders is higher among females than males [49, 50], which could explain the higher proportion of females among participants with mental disorders only. As regards marital status, the literature revealed that participants with mental disorders were more likely to be in a couple than those with substance dependence [13, 15, 48]. Participants with substance dependence may find it more difficult to establish or maintain close relationships. Alcohol abuse plays a role in domestic violence, and is a leading cause of divorce or separation [51]. The association with older age and mental disorders only is more difficult to explain. One hypothesis could be that the frequency of intoxication by alcohol or drugs decreases with age [52–55]. For example, in 2010, the prevalence of drug use in Canada was 25.9 % among individuals between 15 and 24 years old versus 8.1 % for those from 25 and and older [56]. Since alcohol and drug use usually starts at puberty, substance dependence often precedes the appearance of anxiety or mood disorders among young adults [57].

As regards socio-economic variables, the sole difference was the perception of the physical conditions of their neighbourhood, mostly negative among participants with substance dependence only. This could be explained by high expenses for the purchase of drugs or alcohol, which oblige them to find cheap housing. Moreover, living conditions of individuals with substance dependence tend to put them in proximity to drug dealers, thus providing easy access to illicit drugs [58]. Housing problems, criminality and the presence of substance users in the community are significant predictors of substance dependence [8].

As regards health beliefs variable, the sole difference was the poorer perception of physical health among participants with mental disorders only. This could be explained by various diseases (e.g., diabetes, pulmonary diseases) associated with mental disorders [59] or side effects of medication [60]. Another explanation could be that related symptoms associated with anxiety disorders (e.g. hyperventilation, heart palpitation) are general physical.

As regards clinical variables, participants with substance dependence only and those with mental disorders only were different in two variables: psychological distress and impulsiveness. Higher psychological distress was associated with mental disorders as found in a previous study [18]. According to the literature, psychological distress is especially linked to depression and anxiety disorders, especially post-traumatic stress disorder [61]. Conversely, substance dependence was associated with the highest level of impulsiveness, as indicated by the literature [62]. Impulsiveness often results in dropping out of treatment [63] and frequent relapses [64] among individuals with substance dependence.

Finally, as regards service utilization variables, the sole difference was than participants with substance dependence only were less likely to consult a family physician in past 12-months. This was in fact the most significant variable distinguishing the participants with substance dependence only from the two others groups. According to previous studies, individuals with substance dependence only rarely use services until their physical health requires intensive treatment, and even then they are less aware of their physical problems [20, 65]. Furthermore, males are overrepresented among the participants with substance dependence only. Several studies have found that males are less likely to use healthcare services [29, 66–68]. Moreover, like individuals with substance dependence tend to have friends sharing the same behaviour, the latter could be less likely to encourage them to seek help. Individuals with substance dependence could also be victims of stigmatisation from family physicians. A recent study [69] has shown that family physicians tend to dislike this clientele and that they would rather not take on such cases if given a choice. Furthermore, than participants with mental disorders only were more likely to see a family physician could be due to the poorer self-perception they have of their physical health. Somatic symptoms are the main reason why individuals with depression and anxiety disorders would seek primary care [70].

As participants with co-occurring disorders, they shared some particularities with those with substance dependence only and others with those with mental disorders only, and then occupied a middle ground between those two groups. Participants with co-occurring disorders differ from those with mental disorders only in age, marital status, impulsiveness and perception of the physical conditions of their neighbourhood, probably for the same reasons explained earlier for substance dependence only. They were then more likely to be younger, single, to have a higher level of impulsiveness and to perceive negatively the physical conditions of their neighbourhood. Differences were found between participants with co-occurring disorders and those with substance dependence only in gender, level of psychological distress, poor self-perception of physical health and proportion of participants who have visited a family physician. Concerning gender, it is well documented that substance dependence is much more prevalent among males [19, 71–73] and co-occurring disorders among females [4, 24, 74]. The link between psychological distress and co-occurring disorders has also been reported in the literature [75, 76], comorbidity increasing the risk of distress. Moreover, the probability of developing dependence is greater among individuals who consume to reduce their distress [3, 74, 77]. Poorer self-perception of physical health among participants with co-occurring disorders was expected since they tend to be less healthy than those with substance dependence only [16, 78]. As regards service utilization variables, the only difference between substance dependence and co-occurring disorders was the proportion of participants having visited a family physician in previous 12-months. This was unexpected because individuals with co-occurring disorders were usually reported as being heavy service users, mainly for specialised services [16, 20, 79]. The possibility that some participants with substance dependence had also some diagnosis not measured in our study, as personality disorders or schizophrenia, could explain this absence of significant differences.

Limitations

This study presents some limitations. First, it did not include the full spectrum of mental disorders. According to the literature, schizophrenia and personality disorders (not measured in this study) are clearly linked to substance dependence [80–82]. Secondly, as all mental disorders were combined, our results may not be applicable to a sample constituted exclusively of participant having a specific diagnosis. Third, due to the low number of participants with substance dependence only in our sample, alcohol and drug dependence were combined. As for each mental health disorder, it is probable than people with alcohol dependence and drug dependence, with or without mental disorders, have distinct profiles. Finally, the results could reflect the characteristics of the population of the catchment area and may not be generally applicable to other areas or populations.

Conclusion

The study was one of the first in comparing variables associated respectively with substance dependence only, mental disorders only and co-occurring disorders among a general population. The results show complete opposition between substance dependence only and mental disorders only in all the variables included in the regression model, while co-occurring disorders shared variables with each of those two profiles. Moreover, this study was of interest in that it found the importance of a variable usually not considered, the perception of the physical conditions of the neighbourhood as associated with substance dependence only and co-occurring disorders profiles. Health services need to target disadvantaged neighborhoods and promote substance abuse prevention, mainly among young single males, and improve early screening for mental illness and substance dependence to detect individuals with a high risk. Finally, the study shows that while the percentage of participants with substance dependence who used the services of various professionals was higher to that shown in previous epidemiologic studies, a vast majority of that clientele did not visit a family physician. This is in fact the most significant variable that distinguished the individuals with substance dependence only from the other ones. Priority could be given to various strategies (e.g. continuous training programs and shared care involving close coordination between family physicians, psychiatrists, and psycho-social professionals) to increase the capacity of family physicians to take care of individuals especially with substance dependence.

References

Pearson C, Janz T, Ali J: Mental and substancer use disorders in Canada. Health at a Glance. Statistics Canada Catalogue September 82: 264, 2013.

Kessler RC: The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry 56: 730–737, 2004.

Jané-Llopis E, Matytsina I: Mental health and alcohol, drugs and tobacco: A review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and the use opf alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Drug and Alcohol Review 25: 515–536, 2006.

Rush BR, Urbanoski K, Bassani DG, Castel S, Wild TC, Strike C, Kimberley D, Somers J: Prevalence of co-occurring substance use and other mental disorders in the Canadian population. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 53: 800–809, 2008.

De Wit ML, Embree BG, De Wit DJ: Determinants of the risk and timing of alcohol and illicit drug uise onset among natives and non-natives: Similarities and differences. PSC Discussion Papers Series 11: Article 1, 1997.

Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA: The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 28: S51–S62, 2005.

Müller SE, Weijers HG, Böning J, Wiesbeck GA: Personality traits predict treatment outcome in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychobiology 57: 159–164, 2008.

Mckay JR: Continuing care research: What we have learned and where we are going. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 36: 131–145, 2009.

Latkin CA, Curry AD: Stressful neighborhoods and depression: A prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44: 34–44, 2003.

Suvisaari J, Aalto-Setälä T, Tuulio-Henricksson A, Härakänen T, Saarni SI, Perälä J, Schreck M, Castaneda A, Hintikka J, Kestilä L, Lähteenmäki S, Latvala A, Koskinen S, Marttunen M, Aro H, Lönnquvist J: Mental disorders in young adulthood. Psychological Medicine 39: 287–299, 2009.

Pirkola SP, Isometsä E, Suvisaari J, Aro H, Joukamaa M, Poikolianen K, Koskinen S, Aromaa A, Lönnquvist JK: DSM-IV mood-, anxiety- and alcohol use disorders and their comorbidity in the Finnish general population. Result from the Health 2000 Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40: 1–10, 2005.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62: 617–627, 2005.

Compton MT, Weiss PS, West JC, Kaslow NJ: The association between substance use disorders, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and Axis IV psychosocial problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40: 939–946, 2005.

Meade CS, Mcdonald LJ, Graf FS, Fitzmaurice GM, Griffin ML, Weiss RD: A prospective study examining the effects of gender and sexual/physical abuse on mood outcomes in patient with co-occurring bipolar I and substance use disorders. Bipolar Disorders 11: 425–433, 2009.

Wüsthoff LE, Waal H, Ruud T, Grâwe RW: A cross-sectional study of patients with and without substance use disorders in Community Mental Health Centres. BMC Psychiatry 11: 93, 2011.

Donald M, Dower J, Kavanagh D: Integrated versus non-integrated management and care for clients with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: A qualitative systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine 60: 1371–1783, 2004.

Edlund MJ, Harris KM: Perceived effectiveness of medications among mental health service users with and without alcohol dependence. Psychatric Services 57: 692–699, 2006.

Urbanoski K, Cairney J, Bassani DG, Rush BR: Perceived unmet need for mental health care for Canadians with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 59: 283–289, 2008.

Urbanoski K, Rush BR, Wild TC, Bassani DG, Castel S: Use of mental health care services by Canadians with co-occurring substance dependence and mental disorders. Psychiatric Services 58: 962–969, 2007.

Verduin ML, Carter RE, Brady KT, Myrick H, Timmerman MA: Health service use among persons with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 56: 475–480, 2005.

Dickey B, Azeni H: Persons with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and major mental illness; their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 86: 973–977, 1996.

Blanchard JJ, Brown SA, Horan WP, Sherwood AR: Substance use disorders in schizophrenia: Review, integration, and a proposed model. Clinical Psychology Review 20: 207–234, 2000.

Andrews G, Issakidis C, Carter G: Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. British Journal of Psychiatry 179: 417–425, 2001.

Rush BR, Urbanoski KA, Bassani DG, Castel S, Wild TC: The epidemiology of co-occurring substance use and other mental disorders in Canada: Prevalence, service use, and unmet needs. In: Cairney J, Streiner DL (Eds.), Mental disorder in Canada. An epidemiological perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 170–204, 2010.

Tempier R, Meadows GN, Vasiliadis HM, Mosier KE, Lesage A, Stiller A, Graham A, Lepnurm M: Mental disorders and mental health care in Canada and Australia: Comparative epidemiological findings. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 44: 63–72, 2009.

Hasin DS, Grant BF: AA and other helpseeking for alcohol problems: Former drinkers in the US general population. Journal of Substance Abuse 7: 281–292, 1995.

Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, Mandercheid RW, Locke BZ: Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders. Findings from the National Insitute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Archives of General Psychiatry 50: 95–107, 1993.

Cunningham JA, Breslin FC: Only one in three people with alcohol abuse or dependence ever seek treatment. Addictive Behaviors 29: 221–223, 2004.

Narrow WE, Regier DA, Norquist G, Rae DS, Kennedy C, Arons B: Mental health service use by Americans with severe mental illnesses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35: 147–155, 2000.

Torrey WC, Drake RE, Cohen M, Fox LB, Lynde D, Gorman P, Wyzik P: The challenge of implementing and sustaining integrated dual disorder treatment programs. Community Mental Health Journal 38: 507–521, 2002.

Singer E: Nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 70: 637–645, 2006.

Morton LM, Cahill J, Hartge P: Reporting participation in epidemiologic studies: A survey of practice. American Journal of Epidemiology 163: 197, 2006.

Caron J: Predictors of quality of life in economically disadvantaged populations in Montreal. Social Indicator Research 107: 411–427, 2012.

Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36: 1–10, 1995.

Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga J, Berglund P, Arbor A, Bijl RV, Kessler RC, Demler O, Walters EE, Kyliç C, Offord D, Üstün TB, Wittchen HU: Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78: 413–426, 2000.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen HU: The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7: 171–185, 1998.

Statistics Canada: Canadian community health survey- mental health and well-being- cycle 1.2, 2002.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand S-L, Mandercheid RW, Walters EE, Zalasky AM: Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60: 184–189, 2003.

Barratt ES: Impulsiveness subtraits: Arousal and information processing. In: Spence JT, Izards CE (Eds.), Motivation, emotion and personality. North Holland: Elsevier Science Publishers, pp. 137-146, 1985.

Cutrona CE: Ratings of social support by adolescents and adult informants: Degree of correspondence and prediction of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 723–730, 1989.

Baker F, Intaglia J: Quality of life in the evaluation of Community support systems. Evaluation and Program Planning 5: 69–79, 1982.

Kay SR, Wolkenfied F, Murrill LM: Profiles of aggression among psychiatrist patients. I. Nature and prevalence. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 176: 539–546, 1988.

Perkins DD, Long DA: Neighborhoud sense of community and social capital: A multi-level analysis. In: Fisher AT, Sonn CC, Bishop BJ (Eds.), Psychological sense of community: Research, applications and implications. New York, NY: Kluwer, pp. 291–318, 2002.

Caron J, Liu A: A descriptive study of the prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders in the Canadian population: Comparison between low-income and non-low income populations. Chronic Diseases in Canada 30: 84–94, 2010.

Fleury MJ, Grenier G, Bamvita JM, Perreault M, Caron J: Determinants associated with the utilization of primary and specialized mental health services. Psychiatric Quarterly 83: 41–51, 2012.

CIHI: Health care in Canada. Ottawa ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2008.

Lesage A, Vasiliadis HM, Gagné MA, Dudgeon S, Kasman N, Hay C: Prevalence of mental illnesses and related service utilization in Canada: An analysis of the Canadian Community Health Survey. A report for the Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative. Mississauga, ON: Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative, 2006.

Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF: Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 64: 830–842, 2007.

Tuchman E: Woman and addiction: The importance of gender issues in substance abuse research. Journal of Addictive Diseases 29: 127–138, 2010.

Kay A, Taylor TE, Barthwell AG, Wichelecki J, Leopold V: Substance use and women’s health. Journal of Addictive Diseases 29: 139–1633, 2010.

Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R: Alcohol use and intimate partner violence as predictors of separation among U.S. couples: A longitudinal model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 66: 205–212, 2005.

Demers A, Quesnel Vallée A: L’intoxication à l’alcool: Conséquences et déterminants. Montreal, QC: Comité Permanent de lutte à la toxicomanie, 1998.

Adlaf E, Blackburn J, Demers A, Kellner F, Single E, Webster I: Social determinants, alcohol consumption and health: A secondary analysis of Canada’s Alcohol and other drugs Survey (1994) Ottawa: CCSA, 1997.

Midanik LT, Clark WB: The demographic distribution of US drinking patterns in 1990: Description and trends from 1984. American Journal of Public Health 84: 1218–1222, 1994.

Midanik LT, Room R: Epidemiology of alcohol consumption. Alcohol Health and Research World 16: 183–190, 1992.

Canada S (2011) Enquête de surveillance canadienne de la consommation d’alcool et de drogues. Sommaire des résultats http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/drugs-drogues/stat/_2010/summary-sommaire-fra.php#ref, 2011.

Karray Khemiri A, Derivois D: L’addiction à l’adolescence: Entre affect et cognition. Symbolisation, inhibition cognitive et alexithymie. Drogues, santé et société 10: 15–50, 2011.

Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS: Neighborhood disadvantage, stress and drug use among adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42: 151–165, 2001.

Schmitz N, Wang J, Malla A, Lesage A: Joint effect of depression and chronic conditions on disability: Results from a population-based study. Psychosomatic Medicine 69: 332–338, 2007.

Staring AB, Mulder CL, Duivenvoorden HJ, De Haan L, Van Der Gaag M: Fewer symptoms versus more side-effects in schizophrenia? Opposing pathways between antipsychotic medication compliance and quality of life. Schizophrenia Research 113: 27–33, 2009.

Norman SB, Tate SR, Wilkins KC, Cummins K, Brown SA: Posttraumatic stress disorder’s role in integrated substance dependence and depression treatment outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 38: 346–355, 2010.

Wilson NJ, Cadet JL: Comorbid mood, psychosis, and marijuana abuse disorders: A theoretical review. Journal of Addictive Diseases 28: 309–319, 2009.

Zikos E, Gill KJ, Charney DA: Personality disorders among alcoholic outpatients: Prevalence and course in treatment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 55: 65–73, 2010.

White WL: Recovery/remission form substance use disorders: An analysis of reported outcomes in 415 scientific reports, 1868–2011. Philadelphie: Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual DisAbility Services, Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center, 2012.

Spandorfer JM, Israel Y, Turner BJ: Primary care physicians’ views on screening and management of alcohol abuse: Inconsistencies with national guidelines. Journal of Family Practice 48: 899–902, 1999.

Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62: 629–640, 2005.

Carr V, Johnston P, Lewin T, Rajkumar S, Carter G, Issakidis C: Patterns of service use among persons with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Psychiatric Services 54: 226–235, 2003.

Lefebvre J, Lesage A, Cyr M, Toupin J, Fournier L: Factors related to utilization of services for mental health reasons in Montreal, Canada. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33: 291–298, 1998.

Fleury MJ, Imboua A, Aubé D, Farand L, Lambert Y: General practitioners’ management of mental disorder: A rewarding practice with considerable obstacles. BMC Family Practice 13: 19, 2012.

Uzun S, Kozumplik O, Topic R, Jakovljevic M: Depressive disorders and comorbidity: Somatic illness versus side effect. Psychiatria Danubina 21: 391–398, 2009.

Amaro H, Hardy-Fanta C: Gender relations in addiction and recovery. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 27: 325–337, 1995.

Haseltine FP: Gender differences in addiction and recovery. Journal of women’s health & gender-based medicine 9: 579–583, 2000.

Hatgis C, Friedman PD, Wiener M: Attributions of responsibility for addiction: The effects of gender and type of substance. Substance Use & Misuse 43: 700–708, 2008.

Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 54: 313–321, 1997.

Ritsher JB, Mckellar JD, Finney JW, Otilingam PG, Moos RH: Psychiatric comorbidity, continuing care and mutual help as predictors of five-year remission for substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alchohol and Drugs 63: 709–715, 2002.

Schmitz JM, Stotts AL, Averill PM, Rothfleisch JM, Bailey SE, Sayre SL, Grabowski J: Cocaine dependence with and without comorbid depression: A comparison of patient characteristics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 60: 189–198, 2000.

Kessler RC, Nelson CB, Mcgonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66: 17–31, 1996.

Erfan S, Hashim AJ, Shaheen M, Sabry N: Effect of comorbid depression on substance use disorders. Substance Abuse 31: 162–169, 2010

Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE, Walter G: Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): A review of empirical evidence. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 17: 24–34, 2009.

Bradizza CM, Stasiewicz PR, Paas ND: Relapse to alcohol and drug use among individuals diagnosed with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: A review. Clinical Psychology Review 26: 162–178, 2006.

Encrenaz G, Messiah A: Lifetime psychiatric comorbidity with substance use disorders: Does healthcare use modify the strength of associations? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41: 378–385, 2006.

Kelly TM, Daley DC, Douaihy AB: Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addictive Behaviors 37: 11–24, 2012.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CTP-79839). Our sincere appreciation goes to this granting agency as well as to all participants in the research. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest that could bias the present study.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest that could bias the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fleury, MJ., Grenier, G., Bamvita, JM. et al. Profiles Associated Respectively with Substance Dependence Only, Mental Disorders Only and Co-occurring Disorders. Psychiatr Q 86, 355–371 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-014-9335-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-014-9335-1