Abstract

This study focuses on identifying the specific uses of management control tools in public organizations. This research is based on interviews with managers from 43 organizations in the healthcare sector. Data was analyzed and interpreted through the methodology proposed by Gioia et al. Organizational research methods, 16(1), 15-31, (2013). The different uses specified by managers of these organizations were compared with Henri’s work Accounting, organizations and society, 31(1), 77-103, (2006). Findings show matching elements, as well as differences in public sector specificities. This study ends with a discussion about the non-use of existing tools, the multi-uses of tools and the observable dichotomy between political and management uses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of available management tools available for organizations and the issue of their future lies at the heart of several academic studies and, more widely speaking, of social concerns. In academic work, the question of how well management tools are applied motivates empirical research. As such, over the past thirty years, several typologies concerning the future of management tools in organizations have posed the following questions: “How are management tools used by managers?” or – more broadly speaking – “How are management tools used in organizations?” While classifications have been developed over the past decades in the literature in order to understand the use of tools in organizations and societies, none have sought to either differentiate between their uses according to the type of organization (that is to say public or private organizations) or to specify whether their uses in public organizations and private organizations are equally compatible. As well, a significant number of the classifications were developed before the massive influx of management tools in private organizations (and before the identification of new public management). However, public organizations have their own specificities, as has been emphasized in several works (Guthrie et al. 2017). Further research on this subject is relevant and could provide new insights into the field. This article uses the data gathered from 43 interviews to develop an analysis of the uses of management tools in these kinds of organizations. The insights obtained can be used as a base for a study about the need to adapt management uses classifications, as well as to underlie new aspects: non-use, continuous and multi-uses.

Thus, in this study the following questions were considered: Are the classifications of management tools, elaborated on in previous research, adaptable to the public sector? Can there public sector specificities, not previously identified in frameworks that were built for the private sector, be identified?

The Use of Management Control Tools in the Public Sector

According to Lynn (1996), private management is oriented toward economic performance, whereas public management is oriented toward public interest. In addition to the differences observed, obviously there are also the historically late influxes of management control and performance assessment tools into public sector organizations. The issue of their adaptability to the public sector will be considered after highlighting the specificities of these organizations.

The differences between public and private organizations are the basis of managerial differences. Ouellet (1992), though acknowledging the presence of “outstanding similarities” between both types of management, maintains that they are undoubtedly different. He roots this difference in the respective managerial objectives of the public and private sectors: the nature of the action, the goals of the action, the scope and the operating framework.

It has been noted that public organizations, unlike private organizations, regularly seek legitimacy (Verrier 1989), in particular because of the complexity and ambiguity of their objectives (Rainey and Bozeman 2000). This ambiguity not only has a direct impact on management trends within organizations (decision-making legitimacy), but also on interactions with stakeholders. Moreover, public stakeholders are more numerous than in the private sector (Burlaud and Gibert 1984) and are organized in a specific way, specifically due to the payer not being the consumer. For example, some public organizations are financed by state allocations from taxation and not directly by their “clients.” This situation makes the public organizations’ objectives all the more ambiguous, as they cannot easily define their clients. Furthermore, political forces control public organizations, whereas market forces control private organizations (Boyne 2002). Thus, a significant number of public organizations historically come within the scope of a noncompetitive situation (Demeestère 1989), which still exists today in sectors with a public monopoly or quasi monopoly.

However, the differences go far beyond the mere structural and organizational framework; that is, the strategies and cultures belonging to each sector diverge. The public sector has historically rested on management by objectives rather than on results-based management (Demeestère 1989). Cultural (Gibert 1986) and employee worth (Bozeman and Kingsley 1998) differences can also be observed.

One particular sector is of significant interest when studying the use of management tools in public organizations: the healthcare sector organizations. Public health organizations are facing an almost worldwide financial crisis. They are confronted by challenges as the populations of developed countries age and healthcare becomes more and more expensive. Governments seek solutions through new public management and the use of management tools imported from the private sector to rationalize the management of these organizations. Private sector organizations create and diffuse a significant number of management tools. Therefore, governments or supervisory authorities and financiers that have an interest in management tools for health organizations encourage the use of these tools by some of these organizations and monitor their results and developments (Lux and Petit 2016).

Current literature on the use of management tools is broad, but rather divergent. Empirical studies dealing with their uses refer to “types of use,” “roles,” “frequencies” or “durations.” However, it is not easy, in these cases, to understand what these concepts mean. In order to clarify the different concepts, the literature review begins with a presentation of the concept of management tools, followed by (1) a definition of their uses, as applied in this study, (2) an explanation of the main theoretical analysis frameworks, (3) and finally an outline of the framework proposed by Henri (2006).

Management Tools Are Formalized Objects

A management control tool (or more generally a management tool) is “a formal set of reasoning and knowledge variables from an organization, be they quantities, prices, quality levels or any other parameter, with the aim to connect them to different classical managerial actions, which can be summed up with the classical trilogy: foresee, decide, control”Footnote 1 (Moisdon 1997). It is also, as Chiapello and Gilbert (2012) explain, an object “which is well located. For example, a scoreboard has – exactly like an assessment table – a structure and headings, that is to say a materiality. This object shows minimum stability and can be used at a “micro” level, being interdependent with field practices without merging with them (indeed the annual appraisal interview document is not the annual interview; the scoreboard is not the performance management).” This way of considering a management tool enables us to exclude any informal “managerial practices” and to limit the design of the tool to a “formal” object. Hence, a budget is a management tool, just like a formalized procedure, a client satisfaction survey and its results or a questionnaire on the quality of life at work addressed to employees. Management tools can be created by managing staff or by employees of an organization, but they can also come from outside the organization, either for precise enquiries about reporting or control, or – and this is one of the specificities in the public sector – as a proposed tool by government agencies. These tools, once included or developed in organizations, are available for use by individuals.

The Concept of Use: Definition and Qualitative Approach

As Chambat (1994) highlighted, the notion of use may have several meanings: “these could range along the continuum stretching from how something is used, to its appropriation, including the demand, handling and practice.” There is abundant literature on this subject and many researchers have their own definitions of the concept of use of management tools (Bachelet 2004; Breton and Proulx 2002; Docq and Daele 2001; Nobre 2001; Lacroix et al. 1992).

Hussenot’s (2006) synthetic analysis of all works concerning the concept of use leads him to argue for a simplified definition: “what individuals do with an item and how they do it at a precise moment.” This definition is particularly relevant in the context of a study dealing with the practice of management tools in organizations.

However, it should be noted that the definition refers to a qualitative aspect of use and that in Management Sciences the concept of use can also refer to a quantitative aspect. It is also worth distinguishing between “what is done with the item,” and the “reason why it is used,” as well as the frequency and intensity of use, that is to say the “way it is used.” Both perspectives enable this study to consider two specificities of use: a quantitative dimension (frequency and/or time period of use) and a qualitative dimension related to effective use, in the sense of role.

This duality is extended by first looking at use in a qualitative way; in other words, before considering how often a tool is used in an organization, why it is used is posited. Indeed, if a certain management control tool can be employed once a week for reporting (legitimation) and, at the same time, is used twice a month to communicate with employees, are conclusions about its appropriateness the same?

Typological Study of Management Tool Use

There are a significant number of classifications of use of management control tools and their roles within an organization (Henri 2006). As early as 1954, Simon and his colleagues proposed classifying different uses of accounting tools into three categories, each setting forth a question: answer (How am I doing?); attention-directing (What problems should I look into?); problem solving (Of the several ways of doing the job, which is the best?).

Following these first works, several classifications were recommended during the early 1980s to the mid-1990s (Burchell et al. 1980; Hofstede 1981; Ansari and Euske 1987; Simons 1990) emphasizing the different roles of management tools. More recent works dating from the 2000s have yet again proposed new classifications of management tool uses (Hansen and Van der Stede 2004; Henri 2006; Franco-Santos et al. 2007; Speklé and Verbeeten 2014). Most of these classifications are rooted in Burchell et al.’s (1980) or in Simons’s studies (1990).

Henri (2006), in a relevant extension of Burchell et al.’s work, differentiated among four management tool uses (Monitoring, Attention Focusing, Strategic Decision Making and Legitimation). The first kind of use, “Monitoring” (Henri 2006), exists in a simple organizational environment mastered by the manager “where the calculation formulas dominate and are the best way to control the organization” (Berland and Pezet 2009). This practice is part of what Simon (1954) developed under the question “How am I doing?” The aim here is to have feedback on the action, knowing that the latter is characterized by well-known and mastered objectives and easily identifiable and measurable outputs. This use is very similar to what Simons (1995) calls the diagnostic control and what Burchell et al. (1980) call the Answer Machine. Using the example of the budget, Abernethy and Brownell (1999) describe the traditional role of management control tools as assessing performance, making decisions and assigning responsibilities to members of the organization.

The second type of use, “Attention Focusing” (Henri 2006), aims, in particular, to promote a certain position or vision of the organization. This practice occurs when objectives are uncertain and decisions are marked by strong debates and negotiations (Rocher 2008) or more generally when there is a conflict over objectives and means (Burchell et al. 1980). The political dimension is strong. As Berland and Pezet (2009) point out, “Information is used selectively according to the causes that must be defended.” This use is part of the strategies developed by actors in organizations gathering multitudes of stakeholders with different interests (Lux and Petit 2016; Phiri 2017). Use is an “Additional Argument” (Rocher 2008) that can be addressed to certain stakeholders.

The third type of use, “Strategic Decision Making” (Henri 2006), aims to give the manager a better understanding of how the organization works (Berland and Pezet 2009). For Henri (2006) this use refers to the following question posed by Simon (1954): “Of the several alternatives, which is rationally the best?” To answer this question, the management tool is used for ad hoc analysis, for tests of “if-then” models or for sensitivity analyses (Burchell and al. 1980). This use refers to what Burchell et al. (1980) call the Learning Machine.

The fourth and last type of use, “Legitimizing” (Henri 2006), is less developed in the academic literature, is presumably a more political (less rational) role and yet it is very real for organizations. This use refers to the search for legitimacy and justification for the actions undertaken (Burchell et al. 1980). It has an a posteriori use to prove that the decisions taken in uncertain situations are the right ones (Henri 2006; Berland and Pezet 2009). Of course, a legitimation of past actions reinforces the power of the manager in his decision-making of future actions, even in a context of strong uncertainty.

As previously noted, Henri’s work (2006) was inspired by Burchell et al.’s (1980) classification, the last being broadly used in academic literature and, according to Hofstede (1981), adapted for the study of the specificities of management tool practices in public organizations.

Henri’s typology (2006) has been used regarding current management practices within the health sector. This study sought to identify the different uses of management tools in this kind of organization and to discover the typology needed to be adapted according to the specificities just described.

Before introducing the results, the field of study as well as the research methodology is presented.

Research Approach and Field of Study

First, the field of study is presented and particular attention is drawn to the specificities of hospital organizations. Secondly, the methodology used to determine the uses of management tools is examined.

Field of Research

The possible uses of management control tools were determined through survey interviews with 43 operations managers (site managers) in French hospitals (Table 1).

These interviews focused on the managers’ management practices and lasted about two hours. All interviews were recorded and transcribed in full.

French hospitals – which are essentially public or with a public service delegation (in a private and non-profit-making context) – show the same specificities as the public organizations referred to previously. The following is a brief list of common denominators:

-

The complexity and ambiguity of objectives in health organizations – from the patient’s individual care to the collective (social) approach to the health system. In the health field, the issue of whether having a means-based or results-based approach is also essential.

-

The interactions between different stakeholders – indeed health centers are naturally subject to contact with patients (including their families), but also with the state as the supervisory authority, financiers, as well as with regulatory authorities and standardization bodies. All of these stakeholders are also trigger factors for the ambiguity of objectives.

-

A cultural means-based and non-competitive approach. In this case, the issue of performance is problematic (Lux 2016; Lux 2017). Hence, the human aspect of the work is emphasized in order to justify the difficulty of measuring performance on the basis of results.

All of these specificities – compared with private organizations – can be used to explain the different ways to use management tools.

The survey interviews dealing with the use of tools are part of a broader study on management control practices in the health sector. These interviews – lasting from an hour and a half to three hours – focused on the practices of managers in organizations concerning management control. Thus, particular attention was paid to such tools as cost assessment (what a patient, a service or logistics costs), budget tool and control. All data collected was qualitative in nature.

The goal of these survey interviews was to identify what tools could be found in organizations. However, in identifying the uses from a qualitative perspective (“What is concretely done with the tools?”), as well as from a quantitative perspective (“How often and how long?”), the uses were emphasized thanks to examples or overviews given by the people interviewed. This means that whenever an operations manager disclosed the use of a management control tool, one or more concrete illustrations of the context were required, which enabled identifying the context of use and the stakeholders who might be concerned with the latter. Here, the statistics on the use of tools are not highlighted.

Methodology Used for the Analysis of the Collected Data

The method used to analyze the qualitative data is the one chosen by Gioia et al. (2013). This was to ensure that the data under study was meaningful and to give the data a framework with which to confirm the analysis carried out by the researcher.

The first step of analysis took into account the possible types of use of management tools according to the different situations mentioned. Moreover, the second-order themes were built into categories of use. The second step was then dedicated to assessing the appropriateness of Henri’s typology (2006) by considering the possibility of gathering these second-order themes into dimensions matching his categories of use.

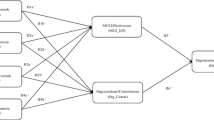

These steps were developed according to the principles of grounded theory referred to by Gioia et al. (2013). The analysis of the data began at the same time as their collection in order to create an enriching iterative process between the newly collected data and emerging theoretical conceptualizations stemming from the previously collected data (Strauss and Corbin 1998; Suddaby 2006). The explanatory factors and their interweavings were thus refined. The analysis was based on three main steps identified by previous research (Pratt et al. 2006): (1) the categorization of verbatims into empirical themes; (2) the conceptualization of these themes into categories, which is relevant when considering our research questions; (3), the connection of these categories into a theoretical model in order to explain the use of management tools.

-

Step 1: Identification of the empirical concepts; first-order analysis. First, first-level codes (Strauss and Corbin 1998) with the aim of describing the thoughts and meanings of the participants’ verbatims were developed. These codes were the first emerging uses of the study. With a view to stabilizing and identifying the importance of these uses, all of the interviews were read over in order to look for verbatims which would come within the scope of these uses. Whenever the latter could not be completed by relevant verbatims, they were rephrased or a parallel was drawn between them and other uses. Examples of verbatims being related to each item of this step are available in Appendix Table 2.

-

Step 2: Construction of conceptual themes; second-order analysis. In this second step, according to Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) recommendations, axial coding was realized with the aim of turning empirical concepts into conceptual categories using an abstraction process. This construction was achieved by “going there and back” among the empirical concepts, the conceptual categories under construction in this study and previous academic works. Whenever a conceptual category seemed to stand out, it was defined within dimensions which were confirmed with the first-level codes (Miles and Huberman 2003).

-

Step 3: Development of an explanatory and predictive model of management tools uses; conception of the aggregate dimensions. The last step of the analysis consisted of finding a way to gather – and draw parallels between – conceptual categories within an inductive, empirical model (Fig. 1). The latter represents the use of management tools emphasized by what the individuals said and the situations that were described. Through an abstraction process of the different themes of use, a parallel between these and the types of uses identified by Henri (2006) was drawn in order to analyze the degree of appropriateness of the study’s findings with this theoretical framework.

Fig. 1 Data structure. (This figure is the application of Gioia’s methodology. The first order concepts are conceived from the interviews (examples of verbatims in Appendix Table 2). These concepts are gathered in second order themes. Then, the themes were compared with the typology from Henri (2006). This comparison gave results relative to the specificities of the uses of management control tools in the public sector)

Results and Analysis

Through an analysis of what managers said about their use of management tools, seven sub-uses and an additional “non-use” category were identified. The gathering and extrapolation of these seven uses were compared to Henri’s (2006) typology. These dimensions mostly confirmed its relevance. However, they also highlighted specific elements, in particular because of the very rationalistic view of the use of tools coming from works on diffusion (Rogers 2003). These elements observed were not specifically mentioned in the various typologies of uses available in the literature. The results are introduced in the following section.

Ghost Machine

In addition to the usual category inherited from Burchell et al.’s typology (1980) and used in Henri’s (2006) work, a new category specific to the observation of the public sector is proposed: the Ghost Machine. Indeed, during the interviews, managers often mentioned the fact that they had many tools that were not particularly useful to them. They were then asked to present these tools and, in particular, their origins. The term Ghost Machine is used in reference to, for instance, answering machines and ammunition machines. The tool is defined as a Ghost Machine when, even though it can be found in the organization, it is not used at all. This implies that no purpose has been assigned to the tool. Thus, the Ghost Machine refers to the concept of non-use, a concept that is missing in the Management Sciences literature. Yet this concept is based on real facts: some management tools do exist (they have been formalized and data have even been added to them), but they are not used. In this case, the concept of the sociology of tools (Jauréguiberry 2010, 2012) and of information systems (Wyatt 2003) was adopted. The non-use refers to a voluntary choice by the individual. This meaning comes very close to what Wyatt (2003) call rejecters (a voluntary relinquishment occurring after a bad experience), evaders or dropouts, the latter being identified by Lenhart and Horrigan (2003) as those who dodge or relinquish. This precision is important as non-use can also refer to very scarce use, which, even though it may happen, is not the focus of this study. Thus, the Ghost Machine is not included in the use and mainly refers to tools that are produced and even processed outside the company, but which can be found in the latter because of an institutional or political diffusion. For example, in a significant number of public organizations, the institutional sector (in particular, regulatory or supervisory authorities) circulates management indicators addressing organizations (in the health sector, this includes activity, staff to patient and cost per patient ratios, which give the companies the opportunity to compare or follow the evolution). This study found that the tool remains in the organization because supervisory authorities provided it, but the authorities do not ask for any feedback. Also, the organization has no need for the tool and will not use it for any purpose but has to keep it because of supervisory authorities’ instructions.

Porosity and Continuity

Of course, frameworks simplify the reality of observed phenomenon. The present study does not criticize this simplification, but instead insists on the continuity and complementarity between the different categories of use. In this study, situations of porosity between categories were observed leading to a few reflections.

“Porosity” characterizes situations where the managerial practice of the tool can only take place by bringing together two forms of use. The porosity of uses thus becomes the means to solve the problem, because a single type of use will not meet the managerial need. The porosity of the uses can also allow the manager to act simultaneously on several needs. Thus, porosity is a situation of cumulation of uses, not necessarily simultaneous (it can be successive), although most of the time it is.

The first line in the study of this porosity can be drawn between monitoring and strategic decision making. What differentiates these two uses is the knowledge of the cause and effect relationships in the organization. In other words, if the relationships are mastered, a decision can be made immediately without a learning process (in other words, the outcome of the decision-making process is already known). Should the opposite occur, decision-making first rests on a learning process. This is precisely where the porosity between both these uses can be observed. The knowledge of the process can be real, without requiring any certainty about the relationship.

In this case, it is likely that the use of the tool will have two facets, namely decision-making together with transformation backing.

Using a rather similar logic, there seems to be porosity between attention focusing and legitimizing. The impact of the level of knowledge on cause and effect relationships depends on the need to legitimize or not the decisions that may be made. When the relationships are mastered, a mere supporting dialogue (beforehand) is sufficient. However, when the relationships are badly mastered, the decision is submitted to concomitant or subsequent legitimation.

Another observation made in this study is that a unique tool can be used in several ways, which thus switches it from one category to another. This multi-use can be simultaneous – there can also be a modification of the type of use of the tool over time within a “life cycle,” which makes it evolve. To try and explain this phenomenon, Essid and Berland’s (2011) analysis of the cognitive overload of the manager as an explanatory element seems particularly relevant in the context of the health sector. This overload can trigger a reduction in the number of tools used, as well as the multiplication of the tools and information being harmful to their follow-up and to their use, which can sometimes lead to non-use, as mentioned above. A tool is thus used by a manager in multiple ways in order to solve the issue of multi-faceted control under the responsibility of one – often isolated – manager in this type of structure.

Political Uses and Managerial Uses

A last observable element is the dichotomous separation between managerial and political uses. The first is dedicated to solving operational and functional issues, whereas the other seeks to influence the different stakeholders related to the organization and to strengthen the position of the tool user. Both these purposes seem to be very different, yet are complementary. Indeed, the dimension of workplace politics is of great importance within public organizations, as mentioned in the introduction. This study found that 20 % of tools have an exclusive political use, linked to legitimization of the decision to external stakeholders (Fig. 2).

Proposition of a Framework

Considering these developments, an integrative framework with reference to Henri’s work (2006) is proposed. The purpose here is to propose a typology of uses (as well as non-uses) of management tools. Any possibility of use – or non-use – originates from the presence of a tool in an organization. The tool, when it is in the organization, may not be used or may be used at a minimal level as a database, which allows a plain follow-up. Above this “basic” use, according to the purposes set up, level of uncertainty and level of knowledge of cause and effect relationships, four types of uses can be identified (Fig. 3).

Use Quantification with the Proposed Framework

The empirical study makes it possible to identify the importance of these uses in public health organizations.

Thus, for the hundred tools observed in the studied public organizations, over 13 tools (13,4) are not used (have no use). Of the remaining 86 (86.6) tools, 38 tools (38.1) have at least one political use and 68 (68.4) have at least one managerial use. Of the 38 tools for political use, 18 are used exclusively for this purpose. In the same way, of the 68 tools for managerial use, 48 (48.5) are exclusively used. Moreover, among these 68 tools, it is possible to distinguish the uses by category or, more precisely, by aggregate, because the managerial uses are cumulative. The set of tools used for managerial purposes is of the monitoring type of use, i.e., 68 tools. However, only 46% of the tools used are based on the Strategic Decision Making type (31 tools) and only 23% on an Attention Focusing type of use (16 tools). It should be read here that of the 68 tools used for monitoring, 31 are also for Strategic Decision Making. Similarly, of the 68 tools used for monitoring, 16 are for Focusing Attention. No tools are used exclusively for the last two mentioned uses, which implies that about a third of the management tools present in public health organizations are only used for monitoring purposes. It can be seen that out of 10 tools available in a public health organization, just under 9 are used, 7 are used for good internal management and fewer than 2 are used with and towards employees (Figs. 4, 5, and 6). These results quantitatively illustrate a number of case studies concerning the appropriation of management tools and the mention of partial uses (Lux and Petit 2016).

Discussion: Contribution to Knowledge of Public Organizations and Management Control Tool Theories

Henri’s work (2006) comes within the scope of a view based on technicality when considering the future of management tools, which is a type of technical determinism stating that, whatever occurs, the tool will somehow be used. However, studies on information systems (Wyatt 2003) and in sociology (Jauréguiberry 2010, 2012) prove that even though there is a tool, it will not necessarily be used – or increasingly used. Thus, including “non-use” to the analysis of management tool uses is proposed. This situation implies two minimal specificities about the management tool – it exists, but is not used. These two elements imply underlying explanations that should be analyzed more comprehensively in future works. They should focus, in particular, on the reasons and workplace politics that are the basis of this type of “non-use.”

Secondly, in previous typologies, a very strict division of uses without, beforehand, considering the possibility of porosity or simultaneous uses is observed. Once more, this seems to be a simplistic view, in particular due to the difficulty of clearly identifying cause and effect relationships in an organization. New works concerning knowledge of cause and effect relationships could improve the analysis of uses (the conception of a measuring tool would be worth considering). The proposal of a spectrum based on the knowledge of relationships, leading to a gray and porous area between the uses, seems more appropriate than a binary system. This study identified the importance of the political dimension of the use of tools in public organizations. Further studies could better enlighten this specificity in the public sector.

In addition, the quantification of uses proposed offers a first reading of management practices in public health organizations. The reading grid derived from Henri’s typology must be able to be used to confirm these practices in other institutions.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to identify whether there are specificities about the uses of tools in the public sector. To that end, using the work of Henri (2006), how tools are used in the healthcare sector was studied. The qualitative data obtained from the interviews, analyzed through Gioia’s methodology, gave insight that his typology obviously provides a sound basis, but also that it has some limitations. Even though validation or generalization of the typology in this study was not sought, elements that give complementary knowledge and enrich the literature have been identified. Interviewed managers testified about the existence of frequent non-used tools identified in this study as “Ghost machines.” Situations of porosity between categories of uses were also observed, with simultaneous, continuous or multi-use situations. Thus, this work gives new insight on the specificities of uses of management tools in the public sector and also provides useful information for public sector tool-designers so that the issues at stake when adapting private sector tools or creating new tools can be understood.

Notes

In this study, all the French quotations were translated into English by a translator.

References

Abernethy, M. A., & Brownell, P. (1999). The role of budgets in organizations facing strategic change: An exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(3), 189–204.

Ansari, S., & Euske, K. J. (1987). Rational, rationalizing, and reifying uses of accounting data in organizations. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(6), 549–570.

Bachelet, C. (2004). Usages des TIC dans les organisations, Une notion à revisiter? Paper presented at the annual meeting of AIM. Actes du 9e colloque AIM INT d’Evry.

Berland, N., & Pezet, A. (2009). Quand La Comptabilité Colonise L'économie et La Société. Perspectives Critiques Dans Les Recherches en Comptabilité, Contrôle, Audit. In D. Golsorkhi, I. Huault, & B. Leca (Eds.), Les Études Critiques En Management, Une Perspective Française (pp. 133–162). Québec: Presses de l’université de Laval.

Boyne, G. A. (2002). Public and private management: What’s the difference? Journal of Management Studies, 39(1), 97–122.

Bozeman, B., & Kingsley, G. (1998). Risk culture in public and private organizations. Public Administration Review, 58(2), 109–118.

Breton, P., & Proulx, S. (2002). L’explosion de la communication. In Sciences et Société, broché/étude. Édition La Découverte: Paris/Montréal.

Burchell, S., Clubb, C., Hopwood, A., Hughes, J., & Nahapiet, J. (1980). The roles of accounting in organizations and society. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 5(1), 5–27.

Burlaud, A., & Gibert, P. (1984). L'analyse des coûts dans les organisations publiques: Le jeu et l'enjeu. Politiques et management public, 2(1), 93–117.

Chambat, P. (1994). Usages des technologies de l’information et de la communication (TIC): Évolution des problématiques. Technologies de l’information et société, 6(3), 249–270.

Chiapello, È., & Gilbert, P. (2012). Les outils de gestion: Producteurs ou régulateurs de la violence psychique au travail? Le travail humain, 75(1), 1–18.

Demeestère, R. (1989). Y-a-t-il une spécificité du contrôle de gestion dans le secteur public? Politiques et management public, 7(4), 33–45.

Docq, F., & Daele, A. (2001). Uses of ICT tools for CSCL: How do students make as their own the designed environment. In Proceedings Euro CSCL 2001, Maastricht, 197-204.

Essid, M., & Berland, N. (2011). Les impacts de la RSE sur les systèmes de contrôle. Comptabilité-contrôle-audit, 17(2), 59–88.

Franco-Santos, M., Kennerley, M., Micheli, P., Martinez, V., Mason, S., Marr, B., & Neely, A. (2007). Towards a definition of a business performance measurement system. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 27(8), 784–801.

Gibert, P. (1986). Management public, management de la puissance publique. Politiques et management public, 4(2), 89–123.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31.

Guthrie, J., Manes-Rossi, F., & Levy, O. R. (2017). Integrated reporting and integrated thinking in Italian public sector organisations. Meditari accountancy research, 25(4), 553–573.

Hansen, S. C., & Van der Stede, W. A. (2004). Multiple facets of budgeting: An exploratory analysis. Management Accounting Research, 15(4), 415–439.

Henri, J. F. (2006). Organizational culture and performance measurement systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(1), 77–103.

Hofstede, G. (1981). Management control of public and not-for-profit activities. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6(3), 193–211.

Hussenot, A. (2006). Vers une reconsidération de la notion d’usage des outils TIC dans les organisations: une approche en termes d’enaction. Colloque international de Rennes: Pratiques et usages organisationnels des sciences et technologies de l’information et de la communication, 158-160.

Jauréguiberry, F. (2010). Pratiques soutenables des technologies de communication. Projectics, 6(3), 107–120.

Jauréguiberry, F. (2012). Retour Sur Les Théories du Non-Usage Des Technologies de Communication. In S. Proulx & A. Klein (Eds.), Connexions: Communication Numérique et Lieu Social (pp. 335–350). Presses Universitaires de Namur: Namur.

Lacroix, J. G., Møeglin, P., & Tremblay, G. (1992). Usages de la notion d’usage: NTIC et discours promotionnels au Québec et en France. Les nouveaux espaces de l’information et de la communication.

Lenhart, A., & Horrigan, J. B. (2003). Re-visualizing the digital divide as a digital spectrum. IT & society, 1(5), 23–39.

Lux, G. (2016). Les représentations de la performance des directeurs d’Etablissements et Services Médico-Sociaux. Revue interdisciplinaire management, homme et entreprise, 21(2), 46–68.

Lux, G. (2017). The Medico-Social Institutes Directors’ perception of performance. Revue Interdisciplinaire Management, Homme & Entreprise 29(5):3

Lux, G., & Petit, N. (2016). Coalitions of actors and managerial innovations in the healthcare and social healthcare sector. Public organization review, 16(2), 251–268.

Lynn, L. E. (1996). Public management as art, science, and profession. Chatham: Chatham House Publishers.

Miles, M., & Huberman, A. M. (2003). Analyse Des Données Qualitatives. Bruxelles: De Boeck Université.

Moisdon, J.-C. (1997). Du Mode D’Existence Des Outils De Gestion. Paris: Ed. Seli Arslan.

Nobre, T. (2001). Management hospitalier: Du contrôle externe au pilotage, apport et adaptabilité du tableau de bord prospectif. Comptabilité-contrôle-audit, 7(2), 125–146.

Ouellet, L. (1992). Le Secteur Public et Sa Gestion. In R. Parenteau (Ed.), Management Public– Comprendre et Gérer Les Institutions De l’État. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Phiri, J. (2017). Stakeholder expectations of performance in public healthcare services: Evidence from a less developed country. Meditari accountancy research, 25(1), 136–157.

Pratt, M. G., Rockmann, K. W., & Kaufmann, J. B. (2006). Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 235–262.

Rainey, H. G., & Bozeman, B. (2000). Comparing public and private organizations: Empirical research and the power of the a priori. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10(2), 447–470.

Rocher, S. (2008). Implantation et rôle d’un outil de gestion comptable. Revue Française de Gestion, 190(10), 77–89.

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press.

Simon, H. A. (1954). Centralization vs. decentralization in organizing the controller's department: A research study and report (no. 4). Controllership foundation.

Simons, R. (1990). The role of management control systems in creating competitive advantage: New perspectives. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15(1–2), 127–143.

Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control: How managers use innovative control systems to drive strategic renewal. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Speklé, R. F., & Verbeeten, F. H. (2014). The use of performance measurement systems in the public sector: Effects on performance. Management Accounting Research, 25(2), 131–146.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Suddaby, R. (2006). From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 633–642.

Verrier, P. E. (1989). Les spécificités du management public: Le cas de la gestion des ressources humaines. Politiques et Management Public, 7(4), 47–61.

Wyatt, S. (2003). Non-users also matter: The construction of users and non-users of the internet. In N. Oudshoorn & T. Pinch (Eds.), How users matter: The co-construction of users and technology. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Both authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Human and Animal Studies

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petit, N., Lux, G. Uses of Management Control Tools in the Public Healthcare Sector. Public Organiz Rev 20, 459–475 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-019-00456-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-019-00456-2