Abstract

In recent years, a historically unprecedented number of Mexican migrants to the U.S. returned to Mexico. Compared to previous cohorts, recent return migrants are distinct in their motivations for return, who they return with, and where they settle. Family reunification remains a pull, but more stringent enforcement of immigration law forced return as a result of deportation, and recent recessions eroded economic opportunities in the U.S. labor market, perhaps spurring others to leave. A growing number of U.S.-born migrants, many with limited experiences in Mexico, are also accompanying family members on return. Increasingly this exceptional flow of migrants is settling outside of traditional sites of emigration/return, dispersing throughout Mexico. This paper addresses how the economic incorporation of this diverse group of migrants varies across regions in Mexico over a transformational period. Using the 2000 and 2010 Mexican Censuses and a 2015 Intercensal Survey, we compare the labor market outcomes of migrants across regions of return. We find that relative earnings of recent cohorts of returnees and U.S.-born migrants are lower than those garnered by previous cohorts. The declining fortunes of individuals with U.S.-Mexico migration experience are largest in the non-traditional northern, southern/southeastern, and central regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past two decades a historically unprecedented number of Mexican migrants to the U.S. have reversed course and returned to Mexico. Family reunification remains a critical pull, but more stringent enforcement of immigration law forced return as a result of deportation (González-Barrera 2015; Masferrer et al. 2012; Masferrer and Roberts 2016; Parrado and Flippen 2016; Villarreal 2014). The economic crisis of the Great Recession eroded opportunities in the U.S. labor market, perhaps spurring still others to leave. Partially as a result, between 2005 and 2010 the number of returnees from the U.S. to Mexico tripled (Masferrer et al. 2012).

Recent return is unique for the changing composition of returnees and the motivations for their return (Gutiérrez Vázquez 2019; Parrado and Gutiérrez 2016). Previous waves of return were often dominated by male labor migrants to the U.S. going back home, frequently to reunite with family, after a temporary sojourn abroad (Hagan et al. 2014; Lindstrom 1996; Massey et al. 2002). For some, working in the U.S. provided capital and skills to start small businesses, reflected in higher rates of self-employment compared to Mexicans with no migration history (Hagan et al. 2014; Papail 2002; Parrado and Gutiérrez 2016). While men remain the majority of more recent returnees, they are increasingly “returning” to new destinations, establishing patterns of migration that stand distinct from traditional short-term circular migration to and from home (Masferrer and Roberts 2012; Riosmena and Massey 2012; Quintana Romero and de la Pérez Torre 2014; Terán 2014). The growth of novel but shared sites of relocation for returnees has tended toward locations with relatively attractive economic opportunities: northern border areas, tourist centers, and large metropolitan areas are increasingly important sites of re-incorporation (Riosmena 2004; Rivera Sánchez 2013; Vargas Valle 2015).

The development of new migration patterns may in part reflect changing reasons for return: immigration enforcement may have locked people in the U.S. who would otherwise have engaged in circular migration while increasing forced return through deportationsFootnote 1 (Gutiérrez Vázquez 2019; Massey et al. 2015). Data from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) show that around 1.5 million Mexican nationals were removed during the Bush administration (2000–2008; DHS 2009) and close to 2 million were deported during the Obama administration (2009–2016; DHS 2017). Thus, an important share of these returnees may arrive in Mexico with few resources to start a business, and little hopes of returning to the U.S., instead quickly engaging in the paid labor market upon return (Gutiérrez Vázquez 2019; Parrado and Gutiérrez 2016). The “mark” of deportation, which is often associated with criminality, may create additional challenges for labor market integration (París Pombo 2010; Wheatley 2011). At the same time, economic conditions in the U.S. eroded considerably between 2008 and 2009. It remains unclear whether the recession contributed to increasing return over this period, but limited labor market opportunities in the U.S. may have encouraged those who did return to enter and remain in the Mexican labor market (Massey et al. 2015; Rendall et al. 2011).

Research on recent return suggests that the economic engagement of returnees is indeed distinct from that observed in previous decades. Parrado and Gutiérrez (2016) show that compared to earlier decades, in 2010, Mexican returnees were less likely to be employers and inactive, statuses associated with business formation and re-migration. They further show that both wage earners and self-employed workers had lower earnings in 2010 in comparison with previous decades, which was true in both new and traditional receiving destinations. Taken together, their results suggest that the recent recession and involuntary nature of return associated with the enforcement of immigration law may have interrupted traditional processes of capital accumulation in the U.S. and investment upon return to Mexico, forcing more returnees into the wage labor market. This is consistent with Campos-Vazquez and Lara (2012), who find that return migrants become less positively selected in terms of education and wages over the same time period.

In more recent work, Gutiérrez Vázquez (2019) and Gutiérrez and Parrado (2016) further show that by 2010 for prime-age men deteriorating economic fortunes are partially attributable to changing educational attainment, heightened likelihood of returnees to live in non-urban areas, increasing engagement in the informal sector, and a shift in occupations of employment. Indeed, male returnees are often not able to translate their migration experiences into upward occupational mobility, and in fact many experience downward occupational mobility (Lindstrom 2013). This previous research is telling, but does not fully capture two important dimensions of heterogeneity that are integral to understanding the new Mexico–U.S. migration: differences in the regional economic contexts of reception and the large shadow migration of the U.S.-born. We will discuss each in turn below.

Regional Economies and Integration

Sites of return present unique opportunities and challenges for return migrants. The Mexican economy is diverse, comprising states with dramatically varying levels of economic development, industrial variety, and poverty rates. For example, while more than 70% of the residents of southern states of Chiapas (77.0%) and Oaxaca (70.4%) were under the federal poverty line in 2016, northern Nuevo Leon had the lowest poverty rate (14.2%) (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social 2017).Footnote 2 In part, these poverty rates reflect the unique types of production across the country, with different regions dominated by agriculture, tourism, manufacturing, or natural resource extraction, that have characterized a long history of unequal regional development in the country (Garza 2000). As a result, locales of settlement offer unique labor markets, in terms of the type of work available, prevailing wages, and the skills/competition of local residents.

Since the mid-1990s, a number of economic shifts have transformed these regional economies. Southern agricultural employment began declining in the latter half of the 1990s following the signing of North American Free Trade Agreement. Manufacturing employment subsequently deteriorated since the mid-2000s in the North, mainly due to a dispersion of manufacturing toward the Bajío (Guanajuato and Querétero, and parts of Aguascalientes and Jalisco) located in the traditional migrant-sending region (Trejo Nieto 2010). These regional sectoral shifts have accompanied labor market changes that spread throughout the entire country. Over the past two decades, informal employment arrangements have become increasingly common, while wage growth has stagnated (Ruiz Nápoles and Ordaz Díaz 2011; Cota Yáñez and Navarro Alvarado 2015). This may be in part attributable to the decline of unionization (Meza González 2005). At the same time, education reform since the late 1990s has increased the average level of education of the Mexican population, although variation across Mexican states is still persistent (Solís 2010). Educational expansion has contributed to the rising importance of educational credentials in securing employment, as well as an increase in employment in the service sector (Hernández Laos 2016; Valenzuela Sánchez and Moreno Treviño 2018). Thus, at the end of a great era of Mexico–U.S. migration, returnees are going back to a vastly transformed Mexican labor market: regional economies have changed, as has the skill composition of the Mexican labor force.

These regions also vary in their histories of migration, with some long accustomed to accepting returnees and others newly struggling to meet their needs. Strategies for integration may vary from place to place: in urban areas, people may downplay their migration experiences, while those in rural areas may rely heavily on networks of family, friends, and community members who are aware of the specifics of the migration experience. At the same time, even migrants who return to communities with long histories of circular migration may find normative patterns disrupted if they are not upwardly mobile upon return. Evidence from Veracruz and Estado de México, for example, shows that returnees had emigrated looking for better labor opportunities, but were not able to translate migration experience into improved jobs or earnings upon returning back to their rural origin communities (Anguiano-Téllez et al. 2013; Mestries 2015; Salas Alfaro 2016). Migrants may also find themselves in new locales to fully capitalize on skills acquired in the migration process. As an example, returnees who emigrated from largely indigenous, rural communities in Oaxaca return back to Oaxaca City after living in urban areas in the U.S. to work in jobs as taxi drivers (men) and housekeepers (women) (Reyes de la Cruz et al. 2017). Similarly, Mayas from rural communities in Yucatán have returned to Mérida or Cancún where job opportunities are more plentiful (Solís Lizama 2018). Even in traditional sending regions like Nayarit, return migrants have settled in Riviera Nayarit, attracted by the booming tourist industry (Becerra Pérez et al. 2015). Similar processes are found in the Northern Highlands of Puebla, where economic integration patterns vary not only by gender and indigeneity, but also by reason for return and by intentions to settle in Mexico or re-emigrate to the United States (D’Aubeterre and Rivermar 2016). Both intentions and economic integration are also influenced by the difficulties reintegrating that other family members are going through. Some returnees, especially those who were not deported, may seek to re-migrate with documentation to the United States, often through the H2 visa program (D’Aubeterre and Rivermar 2016). Considerable ethnographic work has documented the importance of local context of reception on the economic incorporation of returnees. Yet most quantitative studies continue to characterize region of return in terms of traditional versus non-traditional areas.

Shadow Migration

Previous research also fails to consider an important consequence of this return: the growing presence of U.S.-born family members, with limited, if any, previous experience in Mexico. U.S.-born minors, in particular, are increasingly accompanying parents and siblings back to Mexico (Masferrer et al. 2012). Indeed, the flow of recent U.S.-born migrants from the United States to Mexico has increased in absolute numbers from around 80,000 in 1990 to 217,000 in 2015, with the vast majority (three out of four) of the U.S.-born population living in Mexico since 2000 (i.e., the stock) aged 17 or younger (Giorguli-Saucedo et al. 2016). In 2015, almost half a million U.S.-born minors resided in Mexico, and the majority lived with at least one Mexican parent (Masferrer et al. 2019). Going back to a home one has never been to presents unique challenges for integration, especially in the educational system, due to limited Spanish proficiency and problems with foreign credential recognition (van Hook and Zhang 2011; Medina and Menjívar 2015; Zúñiga and Hamann 2015). Indeed, Rendall and Torr (2008) show that in 2000, by age 15 over a quarter of 2nd generation Mexican American children living in Mexico were not enrolled in school, a pattern that persisted in 2010 (Glick and Yabiku 2016). It is thus crucial to consider the activities of U.S.-born minors outside of the education system, and examine how they, too, are integrated into the Mexican labor market. Similarly, many returnees came back with U.S.-born spouses, who enter the labor market at older ages and with limited work experience in Mexico. How these diverse groups of migrants are incorporated remains unclear.

Questions

Given the shift in nature of return and the evolution of the Mexican labor market, how did migrants fare upon return across regions of Mexico? In this paper, we compare the labor market outcomes of Mexican internal migrants, U.S. returnees, and recent U.S.-born migrants to Mexico to those of Mexican non-movers. We document how the relative position of each group in the Mexican labor market changed across regions spanning 2000 to 2015, a period of foundational change in the Mexico–U.S. migration stream. Comparing the experiences of these different groups aids in understanding the social and economic processes that facilitate or prohibit successful integration and sheds light on how migration experience is valued.

Our analysis addresses the following specific questions:

-

1.

How does the economic incorporation of those who returned from the U.S. between 1995 and 2015 vary across regions in Mexico?

-

2.

Do returnees and U.S.-born migrants fare similarly in the Mexican labor market?

-

3.

How do these processes vary for men and women?

The final question is motivated by both quantitative and qualitative evidence that shows that skill transfer on return varies considerably by gender, with women more likely to bring language and interpersonal skills back, facilitating their upward occupational mobility (Hagan et al. 2015). Women are also less likely to migrate back home than men are (Quintana Romero and de la Pérez Torre 2014). At the same time, the Mexican labor market is highly gender segregated, with important regional variations within Mexico (Pacheco 2014; El Colegio de México 2018). Women have low labor force participation rates and work in distinct occupations; in 2015, for example, while 80% of men aged 15 and older were economically active, only 43% of women were (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía 2018).

Data

We pool data from the 10% samples of the 2000 and 2010 Mexican censuses as well as the 2015 Mexico Intercensal Survey gathered by Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) and obtained from IPUMS-International (Minnesota Population Center 2018). We restrict our analytic sample to individuals aged 15 to 59 to focus our analysis on working-age individuals with positive earnings in the year.Footnote 3 We did not include the population 60–64 to reduce biases associated with selective retirement patterns among migrant groups.

Measures

We examine how labor market integration differs for migrant groups that had different foreign education and work experiences, and also varied in the conditions that selected them into return. We use place of birth and residence 5 years prior to the census or survey to define our groups of interest. Non-movers are defined as those born in Mexico who resided in the same state 5 years prior and at the time of the current survey. We define internal migrants as those who changed state of residence in the last 5 years.Footnote 4 Return migration indicates those Mexican-born nationals who resided in a different country 5 years prior (1995, 2005, 2010) to the census. We restrict our group of returnees to those from the United States, and compare also to the recent U.S.-born migrant population, i.e., those who arrived within the last five years.Footnote 5

Our focal dependent variable is the natural logarithm of monthly income from employment. Positive earnings were deflated to 2010 Mexican pesos using the National Consumer Price Index published by INEGI.Footnote 6 Unfortunately, the variable of hours worked is not available for 2015, so we cannot adjust for differences in monthly hours worked. We take into account a host of demographic and human capital characteristics known to impact earnings, including age group (15–24; 25–39; 40–59), sex, marital status (single/never married; married/in union; separated/divorced; widowed), relationship to household head (head, spouse/partner, child, other relative, non-relative), educational attainment in years, class of worker (self-employed; wage/salary workers), and industry of employment.Footnote 7 We differentiate formal/informal salary work by considering access to health and pension plans. We are also interested in how changing contexts of return shape labor market outcomes. To this end, we control for size of locality (less than 2500 people; 2500 to 14,999; 15,000 to 99,999; 100,000 or more), region of settlement (traditional, northern, southern/southeastern, centralFootnote 8) and degree of marginalization in the municipality (ranging from very low to very high).Footnote 9

Methods

Our analysis first describes the nature of migration to Mexico over time for our groups of interest. Doing so establishes the characteristics of different migrants, shedding light on the conditions that selected them into migration and the local labor markets they encounter upon return. We then pool 3 years of data to estimate OLS models that compare the average wages of each group to non-movers over this time period. Our first model shows how the relative labor market position for these groups changed from 2000 to 2015, by interacting migration status with the time period indicator. Our second model adds region and accounts for demographic and human capital characteristics, and contextual measures. Our third model includes a three-way interaction term between migration status, time, and region only, to illustrate how contextual socio-economic conditions that affect labor markets and integration experiences shape wage outcomes.Footnote 10 Our fourth model adds controls for demographic and human capital characteristics, and contextual measures. To account for gender and life course differences, all models are stratified by sex. Men and women differ not only in their participation in the educational system, potential work experience, and position in the labor market, but also on family and household characteristics.

Results

Return Migration, Labor Force Participation, and Wages Across Mexico

Figure 1 maps the total number of returnees by state for the full sample and the sample with positive earnings (employed labor force participants) in 2015, the final year of our analysis. The maps highlight the ongoing importance of traditional sending areas as sites of return and work for both men and women. At the same time, they show how by 2015 returnees had spread beyond the traditional areas. Certain states in the northern, central, and southern/southeastern regions are now important receiving areas for migrants. These states have dramatically different economies and histories of migration compared to both traditional areas and one another. While the number of employed labor force participants was smaller than the total number of migrants, the general regional pattern remains. Women, however, worked in much lower numbers than did men—meaning the majority of female returnees were not working.

Total number of returnees by state for full sample and those in earnings sample, 2015. Source: 2015 Mexico Intercensal Survey. Notes: The earnings sample refers to those aged 15–59 employed with positive earnings. Map A includes the abbreviated names of states. Map B shows the regions defined and used throughout this analysis: northern, traditional, central, and southern/southeastern. The northern region includes Baja California, Baja California Sur, Sonora, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas; the traditional region includes Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Nayarit, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, Guanajuato, Colima, and Michoacán; the center region includes Querétaro, Hidalgo, Mexico, Tlaxcala, Mexico City, Morelos, and Puebla; and the southern and southeastern region includes Guerrero, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo

Table 1 shows the evolution of wages across these regions over time. Strikingly, real wages between 2000 and 2015 were stagnant and actually declined slightly for both non-movers and internal migrants across regions. Yet, real wage deterioration was greatest for those with U.S. migration experience: in the North, where absolute wage decline for men was highest, U.S. returnees in 2000 earned more than 3000 pesos (50%) more each month than those who returned in 2015, perhaps reflecting the much larger wage advantage for earlier cohorts of returnees. And individuals who were born in the U.S. earned around 6000 pesos less in 2015 than in 2000. The dramatic decline, especially in central and traditional regions may reflect a substantial change in who migrated from the U.S. to Mexico in a period of mass deportations and economic decline in the U.S. On the other hand, wages for women with no recent internal or international migration experience rose very slightly from 2000 to 2015, while those who migrated internally saw larger wage gains. Recent returnees and U.S.-born migrants to Mexico, however, saw fairly large wage declines over the period, particularly in traditional and southern/southeastern sending regions. Thus, if the economic situation of women working in Mexico was improving over the decade, returnees were excluded from the gains, particularly in important regions of return.

We next turn to quantifying the magnitude of decline across regions, accounting for the changing composition of recent cohorts of returnees and migrants.

Men in the Mexican Labor Market

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for men with earnings in 2000 and in 2015.Footnote 11 Trends for those without U.S. migration experience, both non-movers and internal migrants, help establish structural change in the Mexican labor market giving insight into the broader conditions U.S. migrants encounter upon return (Parrado and Gutiérrez 2016). The evolution of characteristics of those who remained in Mexico represents a transformation in the nature of the labor market, driven primarily by educational upgrading over the period. Notably, labor market participants with no U.S. experience in all regions were older in 2015 than 2000, with fewer workers between the ages of 15 and 24, a shift that may reflect increased school enrollment of minors following national education reforms. Indeed, the educational attainment of Mexicans without international migration experience increased by over 1.5 years in just 15 years, registering gains among those completing primary education and those with university degrees. While cohorts of returnees from the U.S. were also older by 2015, they were only marginally more educated than those who had returned in 2000, contributing to a greater relative educational disadvantage upon return, particularly in traditional, southern/southeastern, and central regions. U.S.-born individuals in Mexico, who in earlier cohorts had the highest educational attainment, saw their advantage erode: more recent cohorts were not only younger but had lower levels of education, indicating a major change in composition of recent arrivals. If individuals with U.S. migration experience encountered a vastly more educated Mexican labor market upon return, they did so in new areas. In 2000 over 44% of returnees worked in traditional areas of migration, but by 2015, only 35% worked in these areas, instead working more in the south/southeast region. The nature of employment also changed over the period, not so much in the types of work people did but the contractual arrangements under which they worked. All groups were more likely to work in informal positions by 2015. Recent cohorts of U.S. returnees and U.S.-born migrants were considerably less likely to be self-employed than their earlier counterparts. Recent returnees from the U.S. to the northern border region and U.S.-born migrants to the central region were the only groups to maintain similar rates of self-employment, suggesting that small business formation is becoming less common as a strategy for labor market entry upon return.

Men with U.S. immigration experience were working in new areas, different types of work arrangements, and competing with a vastly more educated population upon return. How do these factors relate to the steep decline in real wages observed over the past 15 years? Table 4 presents results from OLS regressions predicting log wages for men with positive earnings. The unadjusted baseline model (Model 1) shows that in 2000, labor market participants who had recently returned from the U.S. earned considerably more than individuals who did not have migration experience, but by 2015, this advantage had eroded entirely. The changing demographics of workers, controlled in Model 2, explain some of the decline. Yet, a large part of the wage deterioration remains unaccounted for by changing patterns of work and settlement.

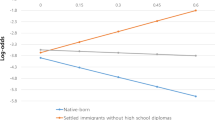

How then do these patterns of wage decline manifest across different regional economies that historically have had divergent histories of emigration? Models 3 and 4 present OLS regressions with a three-way interaction between time, region, and migration status (Table 3). The addition of the three-way interaction shows the difference in wages across time in regions relative to the wage change in the reference group, traditional sending regions. Thus, the interaction between time and migration status reveals average wage change in traditional sending areas. Strikingly, the wage decline of returnees is lowest in traditional areas, characterized by long histories of emigration and return, and strong migrant social networks. Returnees in the region had a relatively small wage advantage compared to Mexican non-movers to begin (Table 1), which erodes by 2015, but is of similar magnitude of the wage deterioration experienced by internal migrants. Still not all of the observed change can be explained by demographic, job, or regional characteristics. Compare traditional areas with the northern region, which throughout the early 2000s was a hub of manufacturing growth. In 2000, returnees experienced a considerable wage premium, but this disappeared almost entirely by 2015 over a time period in which Mexican internal migrants experienced wage gains in the region. While the decline in 2010 was explained somewhat by the changing job and demographic characteristics, almost none of the wage change in 2015 was explained by our measures. Thus if comparing traditional and northern areas, the magnitudes of the decline were exceptionally different, but the patterns that underlie change were similar: jobs, skills, and worker characteristics explained away little. The magnitude of the wage change was similar in the south/southeast—a region that attracted an increasing number of migrants over the period—but a significant portion of wage deterioration was related to shifting job characteristics and skills, a pattern that was very similar for Mexican internal migrants. In the central region, some of the wage deterioration was indeed explained by characteristics, but did not reflect that experienced by internal migrants. Recent cohorts of U.S.-born migrants experienced the sharpest declines, particularly in the southern and central regions. While a large proportion of the decline is explained by observable characteristics, the gaps still remain, suggesting changes in unobserved characteristics or valuation processes in local labor markets. Figure 2a summarizes Model 4, showing the mean estimated wages for each group of men by region over the period.

Women in the Mexican Labor Market

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics for women who participated in the labor force with positive earnings (around 25% of the women in our sample had positive earnings). Like men, by 2015, the age structure of the labor force had changed: women who were working were much older. Again, this shift was accompanied by clear educational upgrading of the Mexican population. For those who remained in Mexico, average years of schooling increased by over a full year from 2000 to 2015. While in 2000, Mexicans with U.S. migration experience had a slight educational advantage, by 2015 returnees were among the lowest formally educated in the Mexican labor force across regions. The U.S.-born, on the other hand, maintained a large but declining relative educational advantage over the period. Only in the northern and traditional regions did recent cohorts of U.S.-born migrants to Mexico have higher levels of education than their previous counterparts. Where women worked also evolved. Returnees continued to work in large proportion in traditional sending areas, but shifted out of the northern region and into the south/southeastern and central regions. U.S.-born migrants to Mexico, however, were more likely to work in the northern region by 2015 than in 2000—indeed 70% of women who were born in the U.S. and working in Mexico in 2015 were concentrated in the northern region, even though both internal migrants and U.S. returnees were less likely to work there. Returnees were also less likely to be self-employed by 2015. Like for men, all women experienced a shift into informal work over the period. Strikingly, though, it was U.S.-born migrants working in Mexico who were most likely to work in informal employment, even though this was clearly the most educated group.

The second panel of Table 3 presents OLS models predicting log employment income, sequentially controlling for demographic, work, and area characteristics. Models 1 and 2 show that the wage deterioration experienced by returnees reflected changes in the type of skills and work returnees performed. Yet still, fully adjusted wage deterioration remained strong over 2010 and 2015. How did this pattern vary across the regions? Models 3 and 4 show that in traditional sending areas—the reference category—recent cohorts experienced about a 10% wage decline that demographic, job, and local area characteristics do little to explain. In the northern areas, the pattern of wage deterioration is similar, with characteristics explaining little of this relationship. The southern/southeastern and central regions register the largest slides in wage for recent working returnees. In both of these regions, wage gaps are reduced when controlling worker characteristics, signaling that changing educational attainment, type of work contract, and industry of employment factor into the declining fortunes of recent cohorts of returnees. Like for men, U.S.-born migrants have the largest deterioration across cohorts, which is smaller only in northern areas. Figure 2b summarizes Model 4, showing the mean estimated wages for each group of women by region over the period.

Mean adjusted monthly employment income for men and women, by migrant status, region, and year, 2000–2015. Sources: 2000 and 2010 Mexican Census and the 2015 Mexico Intercensal Survey. Notes: Mean adjusted employment incomes are estimated from Model 4, which includes a three-way interaction of migrant status, region, and year. Estimates for predicted log employment income are first exponentiated, and then averaged

Discussion and Conclusion

The nature of migration from the U.S. to Mexico continues to evolve. Our results confirm earlier research that documents a shift away from self-employment and into the paid labor force for Mexican-return migrants, as well as a deterioration in economic fortunes for the most recent returnees who left the U.S. compared to earlier cohorts. Several processes may help explain these trends. Weakened economic conditions in the U.S. and an upsurge in deportations over the time period could leave some migrants unprepared for return, a key element for reintegration (Cassarino 2004). Arriving in Mexico without resources, savings, and/or job plans, may lead people to quickly take jobs, potentially in locations which do not offer room for mobility. Research on the undocumented population in the U.S. shows that duration of stay in the U.S. is increasing, with only one in five living in the U.S. for less than 5 years, and half for more than 15 years (Passel and Cohn 2019). Those forcibly returned might not only be unprepared, but have little recent experience in Mexico. While research has shown that using skills and capital acquired abroad facilitates successful business formation (Hagan and Wassink 2016), such a path may be occluded for those who had no plans of return or those with limited resources.

Returnees over this time period also changed where they worked. The wages of recent cohorts declined most outside traditional sending areas, where more and more migrants are settling. That returnees are dispersed beyond traditional sending areas may render their migration experiences more or less visible, which could have positive and negative impacts. Qualitative research in Nezahualcóyotl, a municipality in the metropolitan area of Mexico City, documented divergent patterns of reintegration in the labor market, contingent on whether returnees arrive to origin areas or new destinations (Rivera Sánchez 2013). Unfortunately, data limitations do not allow for identifying reason for return or last place of residence prior to migration and thus, it is unclear how selectivity processes associated with emigration and return explain these divergent experiences in the Mexican labor market. This remains an element to explore in future research.

The results present a more complicated story of integration than previous models establish: returnees are heading to new regions, working in new sectors, and competing against a vastly changed Mexican labor force. While returnees may not have kept up with wholesale educational upgrading, that is not to suggest that they do not return without new, valuable skills. Hagan et al. (2015) and others have demonstrated that returnees come back not only with language abilities, but experience in various types of jobs and with knowledge of new organizational models and business know-how. Some returnees with English-language proficiency, especially those who arrived to the U.S. as children, might work in call-centers where being bilingual would pay off; however, research shows they often work in precarious conditions earning low wages, and can become stuck in this economic niche (Da Cruz 2018). Yet, not everyone gains these skills nor are these skills equally valued. Research in the U.S. shows that low-wage immigrant workers often work with other immigrants, forming linguistic niches, perhaps reducing the imperative to develop language skills quickly or at all (Eckstein and Peri 2018). And in Mexico, unlike the U.S., the trades (oficios) do not offer higher paid blue-collar work. Better understanding of skill translation may aid in building models to explain who enters self-employment versus the paid labor market, a pressing question about the economic incorporation of return migrants across diverse settings (Vlase and Croitoru 2019).

We further shed light on a group whose labor market incorporation has as of yet received little attention: U.S.-born migrants to Mexico. While U.S.-born migrants tend to be more positively selected in terms of education and receive a considerable wage premium relative to both Mexicans without recent international migration experience and return migrants from the U.S., our evidence shows that more recent arrivals are doing considerably worse than earlier cohorts. Previous research on U.S.-born migrants to Mexico has highlighted challenges that minors, in particular, face integrating into an unfamiliar education system, perhaps with limited Spanish-language proficiency. Our results show that integration into the labor market may be a viable option for some. Descriptively, we found that compared to returnees from the U.S., the U.S.-born men were more likely to obtain employment in service industries, like in hotels and restaurants, transportation and communication, real estate and business services, and other services. U.S.-born women were also more likely to work in services, particularly in education and health and social work. These industries may offer improved wage opportunities for these migrants. Yet, our results suggest that this advantage is eroding for more recent arrivals. If these recent arrivals are coming under different circumstances than earlier arrivals—perhaps constrained by a choice to separate from family members or remain in the U.S.—we may witness further deterioration in the future.

The potential for increased deportations under the Trump administration has spurred discussions in Mexico about the challenges of (re)incorporating large numbers of both returnees and U.S.-born minors into various domains of Mexican society, including the labor market, educational system, and community life. Our results document the declining economic fortunes of recent arrival cohorts of Mexican-return migrants, as well as U.S.-born immigrants to Mexico, suggesting that future returnees may indeed experience challenges in the labor market. Migration from the North has taken place within a larger crisis surrounding immigration in Mexico. Indeed, waves of Central American migrants from the South have been met with anti-immigrant sentiment (Meseguer and Maldonado 2015). Such negative views may impact both returnees and U.S.-born migrants in Mexico. While the integration of Mexican and U.S. nationals has occupied policy discussions in Mexico, it remains to be seen how U.S.-born migrants to Mexico, who constitute a truly binational population, will engage with the U.S. educational system and labor market in the coming years.

In light of these changes, integration programs must take into account local labor market contexts. Patterns of emigration and return to the same sending region and the labor market reintegration that they engender are increasingly unlikely. The traditional regions see the most stable (albeit low) wages for returnees over the period, and returnees are less and less likely to go back to those regions. This research highlights that not only are returnees heterogeneous, but so are regional economies. Future research must better tease out selection processes to further disentangle how different groups of return migrants integrate into the Mexican economy, potentially moving us beyond the male sojourner model of previous eras of Mexico–U.S. migration.

Notes

Throughout the paper, we use the term return to indicate the migration of Mexican-born individuals who were living in the U.S. 5 years ago and are in Mexico at the time of the Census. Since we do not have self-reported reasons for return, we do not refer to all migrants as involuntary or forced migrants. Given the scale of DHS-reported removals, it is likely that a large portion of the sample was forced to return against their will, among migrants returning for other reasons, including family reunification, poor health, and completion of target savings (van Hook and Zhang 2011).

These states also differ considerably in extreme poverty prevalence. Whereas over a quarter of the population in Chiapas (28%) and Oaxaca (27%) lived in extreme poverty in 2016, extreme poverty rates in Nuevo León and Baja California were only 0.6% and 1.1%, respectively.

Results remain unchanged when those with zero earnings are included in the analytic sample, by assigning these cases a trivial amount of earnings ($1) before taking the log transformation.

Internal migration at the municipality level was not available for all three time periods.

The recent U.S.-born migrant population has close ties with Mexico, especially younger migrants. We do not have information on ethnic origin, but the 2015 Intercensal Survey asks about citizenship. In 2015, 34% of U.S.-born migrants aged 15–24 are Mexican citizens. One-quarter of those aged 25–39 have Mexican citizenship, and one-sixth of the 40–59 population does. Those without citizenship may become Mexican citizens later if they have at least one Mexican-born parent. Almost half of the recent U.S.-born migrants aged 15–24 are living in a household with a Mexican parent. How dual citizenship facilitates migrant labor incorporation is an open question, but it is associated with access to different social capital. The recent U.S.-born migrant group also differs in terms of human capital. Among those in our estimation samples with positive earnings aged 25–59, 7% of the recent U.S.-born have at least 1 year of postgraduate education (Masters or PhDs), whereas less than 3% of Mexican non-migrants do, and this is only 1% among Mexican returnees from the U.S.

We also excluded extreme outliers, defined as those with earnings greater than four times the standard deviation of year and gender-specific earnings distributions.

Due to small sample sizes for women, we recoded the variable for industry. We grouped together (a) mining and agriculture, (b) manufacturing, electricity, and construction, and (c) financial and real estate services.

Regional boundaries are displayed in the upper-right map of Fig. 1 and defined in the figure’s note. These regions correspond to the ones used by the Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO) based on those defined by Durand and Massey (2003). However, we locate Oaxaca in the southern/southeastern region rather than in the central region, given its similarity in rural and indigenous composition, as well as economic, industrial, and labor market conditions.

The level of marginalization and its categorical version, the degree of marginalization, are widely used in Mexico to characterize conditions of economic and social well-being at the state and municipality level, and are produced by Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO).

Results from models stratified by region lead to similar conclusions.

2010 was omitted for the sake of space, but largely mirrors trends established for 2015.

References

Anguiano-Téllez, M. E., Cruz-Piñeiro, R., & Garbey-Burey, R. M. (2013). Migración internacional de retorno: Trayectorias y reinserción laboral de emigrantes veracruzanos. Papeles de Población, 19(77), 115–147.

Becerra Pérez, R., Cuamea Velázquez, F., & Meza Ramos, E. (2015). Retención de fuerza de trabajo migrante en los servicios turísticos de la Rivera Nayarit. Tepic: Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit.

Campos-Vazquez, R. M., & Lara, J. (2012). Self-selection patterns among return migrants: Mexico 1990-2010. IZA Journal of Migration, 1(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9039-1-8.

Cassarino, J. P. (2004). Theorising return migration: The conceptual approach to return migrants revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 6(2), 253–279.

Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social. (2017). Medición de la Pobreza 2008-2016. Retrieved from https://coneval.org.mx/Medicion/PublishingImages/Pobreza_2008-2016/medicion-pobreza-entidades-federativas-2016.JPG.

Cota Yáñez, R., & Navarro Alvarado, A. (2015). Análisis del mercado laboral y el empleo informal Mexicano. Papeles de Población, 21(85), 211–249.

D’Aubeterre, M. E., & Rivermar, M. L. (2016). Migración de retorno en la Sierra Norte de Puebla a raíz de la crisis económica estadounidense. In E. Levine, S. Núñez, & M. Verea (Eds.), Nuevas experiencias de la migración de retorno (pp. 157–180). México: UNAM, Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte, Instituto Matías ROmero, Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores.

Da Cruz, M. (2018). Offshore migrant workers: Return migrants in Mexico’s english-speaking call centers. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 4(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2018.4.1.03.

De Hoyos, R. E., Popova, A., & Rogers, H. (2016). Out of school and out of work: A diagnostic of ninis in Latin America (Working Paper No. 7548). Washington, DC: The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7548.

Department of Homeland Security. (2009). 2008 yearbook of immigration statistics. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of Homeland Security. (2017). 2016 yearbook of immigration statistics. Washington, DC: Author.

Durand, J., & Massey, D. S. (2003). Clandestinos: Migración México-Estados Unidos en los albores del siglo XXI. Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas y Editorial Porrúa.

Eckstein, S., & Peri, G. (2018). Immigrant niches and immigrant networks in the US labor market. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 4(1), 1–17.

El Colegio de México. (2018). Desigualdades en México 2018. Mexico City: Red de Estudios sobre Desigualdades, El Colegio de México.

Garza, G. (2000). Tendencias de las desigualdades urbanas y regionales en México, 1970-1996. Estudios Demográficos Y Urbanos, 15(3), 489–532.

Giorguli-Saucedo, S. E., García-Guerrero, V. M., & Masferrer, C. (2016). A migration system in the making: Demographic dynamics and migration policies in North America and the Northern Triangle of Central-America. El Colegio de México: Center for Demographic, Urban and Environmental Studies.

Glick, J., & Yabiku, S. T. (2016). Migrant children and migrants’ children: Nativity differences in school enrollment in Mexico and the United States. Demographic Research, 35(8), 201–228. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.8.

González-Barrera, A. (2015). More Mexicans leaving than coming to the US. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Gutiérrez, E. Y., & Parrado, E. A. (2016). Changes in the composition and labor market incorporation of return Mexican migrants between 1990 and 2010. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://paa.confex.com/paa/2016/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/6891.

Gutiérrez Vázquez, E. Y. (2019). The 2000-2010 changes in labor market incorporation of return mexican migrants. Revista Latinoamericana de Población, 13(24), 135–162. https://doi.org/10.31406/relap2019.v13.i1.n24.6.

Hagan, J., Demonsant, J. L., & Chávez, S. (2014). Identifying and measuring the lifelong human capital of unskilled migrants in the Mexico-US migratory circuit. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 2(2), 76–100.

Hagan, J., Hernández-León, R., & Demonsant, J. L. (2015). Skills of the “Unskilled”: Work and mobility among Mexican migrants. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Hagan, J., & Wassink, J. (2016). New skills, new jobs: Return migration, skill transfers, and business formation in Mexico. Social Problems, 63(4), 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spw021.

Hernández Laos, E. H. (2016). Tendencias recientes del mercado laboral (2005-2015). Revista de Economía Mexicana, 1, 87–139.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (2018). Encuesta nacional de ocupación y empleo. Retrieved from https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enoe/15ymas/de.fault.html.

Lindstrom, D. P. (1996). Economic opportunity in Mexico and return migration from the United States. Demography, 33(3), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061767.

Lindstrom, D. P. (2013). The occupational mobility of return migrants: Lessons from North America. In G. Neyer, G. Andersson, H. Kulu, L. Bernardi, & C. Bühler (Eds.), The demography of Europe (pp. 175–205). Dordrecht: Springer.

Masferrer, C., Hamilton, E. R., & Denier, N. (2019). Immigrants in their parental homeland: Half a million U.S.-born minors settle throughout Mexico. Demography. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00788-0.

Masferrer, C., Passel, J., & Pederzini, C. (2012). Selection in times of crisis: Exploring selectivity of Mexican return migration in 2005-2010. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, San Francisco, CA.

Masferrer, C., & Roberts, B. R. (2012). Going back home? Changing demography and geography of Mexican return migration. Population Research and Policy Review, 31(4), 465–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9243-8.

Masferrer, C., & Roberts, B. R. (2016). Return migration and community impacts in Mexico in an era of restrictions. In D. L. Leal & N. P. Rodríguez (Eds.), Migration in an era of restriction and recession (pp. 235–238). Basel: Springer.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Malone, N. J. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Pren, K. A. (2015). Border enforcement and return migration by documented and undocumented Mexicans. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(7), 1015–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.986079.

Medina, D., & Menjívar, C. (2015). The context of return migration: Challenges of mixed-status families in Mexico’s schools. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(12), 2123–2139. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1036091.

Meseguer, Covadonga, & Maldonado, Gerardo. (2015). Las actitudes hacia los inmigrantes en México: Explicaciones económicas y sociales. Foro internacional, 55(3), 772–804.

Mestries, F. (2015). La migración de retorno al campo veracruzano: ¿En suspenso de reemigrar? Sociológica, 30(84), 39–74.

Meza González, L. (2005). Transformaciones del mercado laboral Mexicano. ICE, Revista De Economía, 821, 143–162.

Minnesota Population Center. (2018). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.0 [dataset]. Retrieved from https://international.ipums.org/international/.

Pacheco, E. (2014). El mercado de trabajo en México a inicios del siglo XXI: Heterogéneo, precario y desigual. In R. Guadarrama, A. Hualde, & S. López (Eds.), Dinámicas, transformaciones y significados de la precariedad. Un estudio en tres ocupaciones. Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

Papail, J. (2002). De asalariado a empresario: La reinserción laboral de los migrantes internacionales en la región centro-occidente de México. Migraciones internacionales, 1(3), 79–102.

París Pombo, D. (2010). Procesos de repatriación: Experiencias de las personas devueltas a México por las autoridades estadounidenses (Working Paper). Washington, DC: Mexico Institutem, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

Parrado, E. A., & Flippen, C. A. (2016). The departed: Deportations and out-migration among Latino immigrants in North Carolina after the Great Recession. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 666(1), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216646563.

Parrado, E. A., & Gutiérrez, E. Y. (2016). The changing nature of return migration to Mexico, 1990–2010: Implications for labor market incorporation and development. Sociology of Development, 2(2), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1525/sod.2016.2.2.93.

Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. V. (2019). Mexicans decline to less than half the U.S. unauthorized immigrant population for the first time. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Quintana Romero, L., & de la Pérez Torre, J. F. (2014). La migración de retorno en México: Un enfoque de aglomeraciones desde la nueva geografía económica. In M. Valdivia López & F. Lozano Ascencio (Eds.), Análisis espacial de las remesas, migración de retorno y crecimiento regional en méxico (pp. 239–275). Morelos: Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplanarias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Plaza y Valdés Editores.

Rendall, M. S., Brownell, P., & Kups, S. (2011). Declining return migration from the United States to Mexico in the late-2000s recession: A research note. Demography, 48(3), 1049–1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0049-9.

Rendall, M. S., & Torr, B. M. (2008). Emigration and schooling among second-generation Mexican-American children. International Migration Review, 42(3), 729–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00144.x.

Reyes de la Cruz, V. G., Alvarado, J., Ana, M., & Itzel, Reyes A. (2017). Oaxaca: Migración de retorno y políticas públicas. In R. G. Zamora (Ed.), El retorno de los migrantes mexicanos de los Estados Unidos a Michoacán, Oaxaca, Zacatecas, Puebla, Guerrero y Chiapas 2002-2012 (pp. 205–230). México: Universidas Autónoma de Zacatecas-Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Riosmena, F. (2004). Return versus settlement among undocumented Mexican migrants, 1980 to 1996. In J. Durand & D. Massey (Eds.), Crossing the border: Research from the Mexican migration project (pp. 265–280). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Riosmena, F., & Massey, D. S. (2012). Pathways to El Norte: Origins, destinations, and characteristics of Mexican migrants to the United States. International Migration Review, 46(1), 3–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2012.00879.x.

Rivera Sánchez, L. (2013). Migración de retorno y experiencias de reinserción en la zona metropolitana de la ciudad de México. Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana, 21(41), 55–76.

Ruiz Nápoles, P., & Ordaz Díaz, J. L. (2011). Evolución reciente del empleo y el desempleo en México. Economía UNAM, 8(23), 91–105.

Salas Alfaro, R. (2016). El retorno de los mexiquenses que emigraron a Texas. In J. Olvera García & N. Baca Tavira (Eds.), Continuidades y cambios en las migraciones de México a estados Unidos. tendencias en la circulación, experiencias y resignificaciones de la migración y el retorno en el Estado de México (pp. 231–256). México: UAEM-UTSA.

Solís, P. (2010). La desigualdad de oportunidades y las brechas de escolaridad. In A. Arnaut & S. Giorguli (Eds.), Los grandes problemas de México: Educación (pp. 599–622). México, D. F.: El Colegio de México.

Solís Lizama, M. (2018). Aproximaciones al análisis de la precariedad laboral de la migración de retorno. Un estudio comparativo entre migrantes yucatecos. Norteamérica, 13(1), 7–32.

Terán, D. (2014). La migración entre México y Estados Unidos hacia una nueva geografía del retorno del siglo XXI (Doctoral dissertation). El Colegio de México AC, Mexico City.

Trejo Nieto, A. B. (2010). The geographic concentration in Mexican manufacturing industries, an account of patterns, dynamics and explanations: 1988-2003. Investigaciones Regionales, 18, 37–60.

Valenzuela Sánchez, N. A., & Moreno Treviño, J. O. (2018). Asignación y retorno de habilidades en el mercado laboral en México. Revista de Economía Laboral, 15(1), 1–33.

van Hook, J., & Zhang, W. (2011). Who stays? Who goes? Selective emigration among the foreign-born. Population Research and Policy Review, 30(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-010-9183-0.

Vargas Valle, E. D. (2015). Una década de cambios: Educación formal y nexos transfronterizos de los jóvenes en áreas muy urbanas de la frontera norte. Estudios Fronterizos, 16(32), 129–161.

Villarreal, A. (2014). Explaining the decline in Mexico-US migration: The effect of the Great Recession. Demography, 51(6), 2203–2228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0351-4.

Vlase, I., & Croitoru, A. (2019). Nesting self-employment in education, work and family trajectories of Romanian migrant returnees. Current Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392119842205.

Wheatley, C. (2011). Push back: US deportation policy and the reincorporation of involuntary return migrants in Mexico. The Latin Americanist, 55(4), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1557-203X.2011.01135.x.

Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2015). Going to a home you have never been to: The return migration of Mexican and American-Mexican children. Children’s Geographies, 13(6), 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2014.936364.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by Fondo Sectorial SEDESOL-CONACYT through the project “Variaciones geográficas de los procesos de integración de jóvenes migrantes: la importancia del contexto local de retorno y acogida” (#292077). We thank Marlen Guerrero, Francisco Flores Peña, Abigail Tun Mendicuti, and Natalia Oropeza Calderón for their excellent research assistance. We benefited from discussions of the preliminary results of this paper at the Population Association of America and the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population meetings, and from feedback from three anonymous reviewers. All mistakes remain our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Denier, N., Masferrer, C. Returning to a New Mexican Labor Market? Regional Variation in the Economic Incorporation of Return Migrants from the U.S. to Mexico. Popul Res Policy Rev 39, 617–641 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-019-09547-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-019-09547-w