Abstract

This study examined if differences exist in the number and timing of antenatal care (ANC) visits for users of public and private health care facilities in Ghana. Also, the study explored if such variations could be attributed to health-provider factors or the selective socioeconomic characteristics of the users. Data were drawn from the recently collected Ghana Demographic and Health Survey and from a representative sample of t 2135 women who attended antenatal care in a health facility 6 months preceding the survey. Random-effects Poisson and logit models were employed for analysis. Results showed statistically significant differences between users of private and public health facilities for number of ANC visits, but not for the timing of such visits. Although some health-provider factors were significantly associated with ANC visits, these factors did not explain why users of private health facilities had significantly higher number of ANC visits than users of public health facilities. Differences in ANC visits for both private and public health facilities were rather explained by the selective socioeconomic characteristics of the users, especially as wealthy and educated women patronized private health care than poorer and uneducated women. The study concludes that Ghanaian women attending private health facilities may not have improved access to antenatal care compared to those attending public health facilities, and adds to the emerging body of literature that questions private health care in sub-Saharan Africa as more effective than public health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Even beyond targets set by the United Nations, Ghana has continued to make progress towards reducing maternal mortality. Although slow, maternal mortality rates declined from 634 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 319 per 100,000 live births in 2015 (Ghana Development Planning Commission 2015). Also, the adoption of the Millennium Development Goal Acceleration Framework (MAF) provides further evidence that Ghana’s maternal mortality rate may reduce in the future. The plan towards future reductions is consistent with United Nations’ most recent objective of helping low- and middle-income countries prioritize and sustain development goals (SDGs) in the future (United Nations 2011). In the more specific case of Ghana, several governmental and nongovernmental interventions have contributed to gains in maternal health. For instance, with some few notable exceptions, the implementation of the free maternal health policy under the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) exposed Ghanaian women to a variety of subsidized and comprehensive maternal health services (Opoku 2009; Ganle 2015; Chaitkin et al. 2015). An evaluation of the free maternal health policy in Ghana since its introduction in 2008 indicates a steady rise in facility-based deliveries and increased utilization of maternal health services (Hera-HPG 2013; Dixon et al. 2014). Similarly, the Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI), the Prevention of Maternal Mortality Programme (PMMP), and the High Impact Rapid Delivery (HIRD) programme are some few but important interventions by the Ghana government to improve antenatal health access and outcomes of women in Ghana.

In the larger scheme of events, providing antenatal care to pregnant women constitutes a major part of the maternal health delivery system in both developed and developing countries. Antenatal visits to the health facility are useful in diagnosing infections and complications that may endanger successful parturition. Besides, women are provided with a range of information, including those related to birth preparedness, place of delivery, signs of serious complications with the pregnancy, and a chance to interact and make important decisions with health care providers (GSS, GHS & ICF International 2015; Baffuor-Awuah et al. 2015). It is often recommended that women make early visits, preferably in the first three months of pregnancy and also make such visits to the hospital at least four times during pregnancy (Lincetto et al. 2006). To improve the antenatal experience of women in Ghana, the government adopted the focused antenatal approach (FANC) in 2002 (see Baffuor-Awuah et al. 2015). FANC has the ultimate aim of reducing maternal mortality by improving wait-time during antenatal care, increasing direct contact between clients and doctors and addressing obstacles to successful health delivery for pregnant women at the health facility (Baffuor-Awuah et al. 2015). It is thus not too surprising that recent surveys report significant improvements in Ghanaian women’s utilization of antenatal health services. It is reported, for instance, that about 97 % of Ghanaian women received antenatal care from a skilled provider, while about 87 % also made at least four antenatal visits to the health facility in 2014 (GSS, GHS & ICF International 2015).

This significant progress could be attributed partially to sustained research and government interventions, but several questions remain. For instance, research demonstrates that health-provider factors influence both attendance and timing of ANC visits (Pell et al. 2013; Wilunda et al. 2015; Chama-Chiliba and Koch 2013). It is also largely documented that such health-provider factors differ significantly among Ghanaian public and private health care providers (Nketiah-Amponsah and Hiemenz 2009; Aikins and Ahmed 2014; Turkson 2009; Basu et al. 2012). Yet, previous research has rarely examined whether women’s access to antenatal health care differ by type of health facility. We fill this important research gap by first, examining whether significant differences exist between private and public hospitals regarding women’s access to antenatal care visits; and second, determining whether such differences can be explained by variations in health-provider factors.

Background

Health systems in Ghana have been described as complex, pluralistic, and multifaceted (Gaddah and Munro 2011; Salisu and Prinz 2009). Largely controlled by the government through the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Ghana Health Service (GHS), public health systems in Ghana are administered at the national, regional, district, subdistrict, and community levels (Nketiah-Amponsah and Hiemenz 2009; Gaddah and Munro 2011; Salisu and Prinz 2009). As the largest health provider to the Ghanaian populace, the public health system is considered modern and one that continues to strive for equity, especially with the introduction of the National Health Insurance Scheme—a universal health coverage system. In recent years, however, the public health system is reported as confronted with severe challenges of delivering effective and efficient services to Ghanaians.

There is emerging evidence, however, that private health care providers deliver a significant proportion of health services in low- and middle-income countries, including Ghana (Montagu et al. 2011). Currently, private providers contribute about 35 % of services used by Ghanaian health seekers, and this is expected to grow in the future (Markinen et al. 2011). Also, with the introduction of ‘locum’— a system that allows medical personnel in public hospitals to work extra hours and make additional income in the private hospitals—the Ghanaian health delivery system has continued to witness mobility of labor between public and private hospitals. Private health care in Ghana comprises mainly of formal health care providers (medical doctors, pharmacists, nongovernmental organizations) and informal health care providers (herbalists, traditional birth attendants, etc.), and appear to be an attractive alternative to the public health delivery system. Also, it has been argued that the private health sector emerged largely as a result of the inefficiencies in the public health delivery system (Obuobi et al. 1999; Lewis 2006). Thus, the perceived efficiency of private health care in Ghana adds to the general and growing perception that they are better and associated with higher levels of satisfaction and quality compared to public health care (Nketiah-Amponsah and Hiemenz 2009; Aikins and Ahmed 2014; Turkson 2009).

Previous literature comparing private and public health delivery systems in sub-Saharan Africa identified the former as responsive to the needs of clients. Private health facilities are often chosen over public health care for their accessibility, shorter wait-times, privacy and confidentiality, and general responsiveness to patients’ needs (Adesanya et al. 2012; Agha and Keating 2009; Montagu et al. 2011). Some studies in Ghana Nigeria, Kenya, and Tanzania show that wait-times, client–health-provider relations and hospital conditions are better in private health facilities than public health delivery avenues (Adesanya et al. 2012; Agha and Keating 2009; Hutchinson et al. 2011; Nketiah-Amponsah and Hiemenz 2009; Basu et al. 2012). Notwithstanding, private health facilities are known for their higher out-of-pocket user fees and may not be accessible to Ghanaians who do not have the resources to pay.

While the literature is very clear on health-provider differences between private and public health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa, it is inconclusive on whether these differences have implications for health outcomes, including access to antenatal health services. Notably, Olusanya et al. (2010) examined factors associated with maternal preference for delivery in private hospitals in Lagos, Nigeria. While their study elicited reasons for women’s choice of place of delivery, either private or public, it only focused on urban populations and did not test whether health-provider differences determined women’s choice of health facility. In their synthesis of the literature on the effects of public and private health strategies for improving health outcomes, Montagu et al. (2011) found significant reductions in mortality for patients receiving care in private hospitals compared to those in hospitals. However, the authors concluded that there was the need for more evidence that compared private and public sectors especially in low-income settings where there is extreme paucity of studies. After a comprehensive review of the literature, Basu et al. (2012) concluded that although public health care providers lack timeliness and hospitality towards their clients, scientific evidence does not support claims that private health facilities are more efficient and accountable than public health facilities.

For some authors, the difference in health outcomes between private and public health providers may not solely rest with health-provider factors, but also the individual-level characteristics of those who access these facilities (Montagu et al. 2011; Regidor et al. 2008; Basu et al. 2012). It is widely documented that users of private health facilities tend to belong to the higher socioeconomic echelons of society mainly because they can afford user fees charged at these facilities or are on private health insurance programs that enable access to private health care. Given that the extant research finds socioeconomic gradients in health access, in particular antenatal care visits (Banchani and Tenkorang 2014; Victoria et al. 2009; Afulani 2015; Dixon et al. 2014; Asamoah et al. 2014), it is possible that variations in health outcomes between private and public health care facility users may just be an artifact of the socioeconomic differences between individuals accessing these facilities. Thus, this study contributes to the literature on health systems and health care in sub-Saharan Africa by examining if significant differences exist among private and public health care providers regarding access to antenatal care for women in Ghana, and if such variations can be attributed to differences in health-provider characteristics or the socioeconomic disparities among users of these facilities.

Data and Methods

Data for this study are drawn from the recently collected Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. The 2014 GDHS is a nationally representative dataset administered by the Ghana Statistical Service and ICF Macro, Inc, and the sixth in such surveys of the Global Demographic and Health Surveys Program. The GDHS provides high quality and reliable data on demographic and health-related issues including fertility, morbidity and mortality, sexuality, HIV/AIDS, and more recently, chronic diseases. The inclusion of detailed data on health-provider characteristics and the type of health facility used by respondents makes the most recent survey appropriate for this study. Although data were collected for men, women, and children, the women’s data were used for this study.

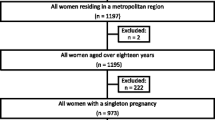

The GDHS employed a two-staged stratified sample frame where systematic sampling with probability proportional to size was used to identify enumeration areas from which households were selected. The GDHS identified about 9656 eligible women aged 15–49 years from 11,835 households out of which 9396 were interviewed yielding a response rate of 97 %. Data were collected by a team of trained interviewers under the supervision of senior staff from the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) with technical input from ICF Macro International, Inc. (Ghana Statistical Service 2015). Interviewers were trained in both English and the local languages. The survey protocol was reviewed by the Ghana Health Service Ethical Review Committee and the Institutional Review Board of Macro International (a US-based organization that collaborates and provides technical assistance to DHS) (Ghana Statistical Service 2015). The sample for this study was restricted to about 2135 women who made their antenatal visits to the health facility in the last 6 months preceding the survey.

Measures

Two main outcomes measuring antenatal coverage were employed in this study. However, these outcomes were limited to those who had visited the health facility in the last 6 months preceding the survey, especially as data on health-provider characteristics were asked from these respondents only. The first question asked respondents: ‘How many times did you receive antenatal care for this pregnancy?’ and the second question also asked: ‘How many months pregnant were you when you first received antenatal care for this pregnancy?’ The first outcome is a count variable measuring the number of times women received ANC for their pregnancy, while the second measured the timing of the first visit. The WHO recommends that women make at least four antenatal visits, the first of which should be in the first 3 months of the pregnancy.

The focal independent variable employed in this study measured where women received their antenatal care. Specifically respondents were asked: ‘Where did you receive antenatal care for this pregnancy?’ with responses categorized into government/public and private hospitals. Variables measuring health-provider characteristics include the following: accessibility of health facility, condition of health facility, satisfaction with services by staff, wait-time at the health facility, and interpersonal relationships and friendliness of the health providers. All latent variables are scalar measures created using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). For instance, accessibility of the health facility is a summative index weighted by factor loadings derived from these variables: In your opinion, was it very easy, easy, fairly easy, difficult, or very difficult to see the health provider?; Is the location of the health facility very convenient, convenient, fairly convenient, not convenient or very inconvenient for you?; Are the hours the health facility open during the day very good, good, fair, poor, or very poor for you?. Response categories are on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = very good and 5 = very poor. Response categories for all three variables were reverse coded for easy interpretation. Thus, positive values on the scale indicate easy access, while negative values indicate difficult access. Factor loadings ranged from 0.771 to 0.799 and reliability coefficient Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.69. Condition of health facility is a summative index derived from these variables: Were you very satisfied, satisfied, fairly satisfied, not satisfied, or very dissatisfied with: (a) the cleanliness of the health facility?; (b) the ease of finding where to go?; (c) comfort and safety while waiting?; (d) privacy during examination?; (e) confidentiality and protection of personal information? All variables were reverse coded as ‘very dissatisfied = 1’ to ‘very satisfied = 5.’ Positive values on scale indicate very satisfied with condition of health facility while negative values mean otherwise. Factor loadings ranged from 0.734 to 0.826 and Cronbach’s Alpha is 0.85. Similarly, satisfaction with services by staff is a scale derived from these variables: Were you very satisfied, satisfied, fairly satisfied, not satisfied, or very dissatisfied with the staff at the health facility when they: (a) Listened to you?; (b) Explained what you wanted?; (c) Gave advice and information on options for treatment? All variables were reverse coded as ‘Very dissatisfied = 1’ to ‘very satisfied = 5.’ Positive values on scale indicate very satisfied with staff of health facility, while negative values mean otherwise. Factor loadings ranged from 0.841 to 0.921 and Cronbach’s Alpha for the scale is 0.86.

Wait-time at the health facility is a summative index weighted by factor loadings derived from these variables: Were you very satisfied, satisfied, fairly satisfied, not satisfied, or very dissatisfied about: (a) Time to wait for your turn; (b) Time spent in consulting/examination room; (c) Time at pharmacy/dispensary. All variables were reverse coded as ‘very dissatisfied = 1’ to ‘very satisfied = 5’. Positive values on scale indicate very satisfied with wait-time at the health facility, while negative values mean otherwise. Factor loadings ranged from 0.844 to 0.859 and Cronbach’s Alpha estimated as 0.89. Interpersonal relationships and friendliness of the health providers was derived from these variables: In your opinion, did your health provider spend enough time with you?; Did the health provider seek your consent before providing treatment?; Was the health provider friendly to you?. All questions are dichotomous with response categories ‘no-0’ and ‘yes = 1.’ Positive values on the scale mean health provider was friendly and caring, while negative values mean otherwise. Factor loadings range from 0.709 to 0.777 and Cronbach’s Alpha was estimated as 0.58.

Socio economic variables used include educational background of respondents (no education = 0; primary education = 1; secondary education = 2; higher education = 3), employment status of respondents (not employed = 0; employed = 1), and wealth status, a composite index based on the household’s ownership of a number of consumer items including television and a car, flooring material, drinking water, toilet facilities, etc. (poorest = 0; poorer = 1; middle = 2; richer = 3; richest = 4). Respondents’ marital status, religious affiliation, ethnic background, residential status, health insurance status, age, and distance to health facility are used as control variables.

Analytical Strategies

We use Poisson and logit regressions to analyze both outcome variables, respectively. Poisson regression was used for the count variable ‘number of antenatal visits.’ Counts are usually positive integers that follow a Poisson rather than a normal distribution, making the Poisson regression appropriate for estimations than the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) approach (Mullahy 1986; Lawless 1987; Dean and Lawless 1989). An important assumption of the Poisson distribution is that the estimated conditional mean will be equal to the conditional variance for the data under consideration (Lawless 1987). Logit models were also used to examine the timing of first antenatal visit, which was divided into early antenatal visit, mostly within the first 3 month of pregnancy (0–3 months) and visits beyond the first trimester (4 months and beyond). This technique was chosen over an event history model mainly because all respondents had experienced their first antenatal visit and none remained to be right-censored, a strong basis for which event history techniques are often chosen over less dynamic ones including logit models.

Both Poisson and logit models are built under the assumption of independence of subjects but the GDHS has a hierarchical structure with respondents nested in households and enumeration areas (EAs). Thus, there is a good chance that this assumption will be violated given that respondents are clustered in households and EAs. The violation of this important assumption may bias standard errors downwards with implications for the inferences and conclusions drawn for this study. We handle this methodological challenge by building random intercept models that enable us determine if the antenatal experience (number and timing of visits) of women differ across households and EAs, and if clustering within the data is large and significant (Pebley et al. 1996; Guo and Zhao 2000; Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). The extent of clustering in our models was measured using intraclass correlations (ICC). For the Poisson regression, the ICC at the household and cluster levels was estimated as

where 1 is the variance at level 1 and τ 2 α and τ 2 β are the variances at the household and EA levels, respectively. With the variance at level 1 changed to \(\frac{{\pi^{2} }}{3}\), the ICC for logit models can also be estimated (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). All models are estimated using the Generalized Linear Latent and Mixed Models (GLLAMM) available in STATA. Logit and Poisson coefficients can be transformed into odds ratios (OR) and incidence risk ratios (IRR) by exponentiating the coefficients, respectively. Thus, a positive logit coefficient will imply respondents are more likely to visit in the first 3 months of their pregnancy compared to visiting beyond the first 3 months and vice versa. Also, a positive Poisson coefficient means the visiting rate for women with certain characteristics may increase by some percentage or factor and vice versa.

Results

Descriptive Results

Descriptive results are presented through Tables 1, 2, and 3. Results show that the majority of women attended public hospitals for antenatal care compared to private hospitals (89.6 vs. 10.4 %). On the average, women made about 6.6 antenatal visits to the health facility (see Table 1), which is higher than the recommended four visits by the WHO. However, there were statistically significant differences in antenatal visits by type of health facility. Respondents who used private health facilities visited more often (7.2 visits) than those attending public hospitals (6.5 visits). In keeping with the WHO’s recommendations, 94.6 % of women attending private hospitals made more than four visits for antenatal care compared to 90.8 % for public hospitals (not shown). Also, the majority of women (67.7 %) visited the health facility within the first trimester. A higher proportion of women using private hospitals made their first antenatal visit earlier compared to those in public hospitals (70.9 vs. 67.4 %), although this difference was not statistically significant. Generally, women accessing health facilities for antenatal care were satisfied with the services provided by the medical staff and friendliness of the health provider, although dissatisfied with accessibility, wait-time, and condition of the health facility. It is important to note, however, that significant differences exist between public and private hospitals regarding these health-provider characteristics. For instance, Table 2 shows that users of private health facilities were satisfied with accessibility and condition of the facilities compared to users of public health facilities. We did not find significant differences between private and public hospitals for other health-provider factors, such as wait-time, satisfaction with services delivered by the staff, and friendliness of the health provider. Sharp socioeconomic differences exist between users of private and public hospitals. Compared to the uneducated and poorer women, educated and wealthier women were significantly more likely to use private health facilities than public health facilities.

Table 3 shows the zero-order unadjusted Poisson and logit coefficients for number and timing of antenatal visits, respectively. Results showed that the expected log count of the number of ANC visits was higher (b = 0.074; IRR = 1.08) for users of private health facilities compared to users of public health facilities. In other words, the visiting rate for users of private health facilities increased by 8 % compared to users of public health facilities. We did not find significant differences between private and public health facilities for timing of first visit. Some health-provider factors were significantly associated with both the number and timing of ANC visits. Women who were satisfied with accessibility of the health facility had a higher expected log count of ANC visits (b = .021; IRR = 1.02). Similarly, women who were satisfied with the friendliness of the health provider had a higher expected log count of visits and were more likely to visit in the first trimester. There are clear socioeconomic gradients in access to ANC as women with higher education and wealth had higher expected log counts of visits and made such visits in the first trimester of pregnancy, compared to uneducated and poorer women.

Multivariate Results

Table 4 shows the adjusted Poisson and logit coefficients for choice of health facility and other selected independent variables. In all, three models are estimated each for number and timing of ANC visits, respectively. As significant differences exist between private and public health facilities for number of ANC visits at the bivariate level, we examined if these differences could be explained by the health-provider characteristics. Thus, the first multivariate model included all variables for health-provider factors; the second model added the socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents; and the third model included some control variables. In all these models, we estimated the magnitude and significance of clustering.

As shown in model 1 of Table 4, statistically significant differences between private and public health facilities are observed for number of ANC visits even after controlling for health-provider factors (b = 0.072; IRR = 1.08). The coefficient remained statistically robust and did not change from what was observed at the bivariate level. Similar to the bivariate analysis, accessibility of the health facility was positively associated with number of visits for ANC. Friendliness of the health provider was marginally significant and had a positive association with number of ANC visits. Generally, the results suggest that health-provider factors could hardly explain the differences between private and public hospitals. However, this difference vanished completely after the socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents were included in model 2, suggesting that the difference between private and public health facilities in relation to ANC visits is simply a reflection of the socioeconomic differences between the users of such services and not institutional differences per se. The results did not change even after other control variables were added. It was observed that all health-provider factors were not significant except the variable measuring friendliness of the health provider.

As shown in the bivariate analysis, results in model 4 indicate no statistically significant differences between private and public health facilities for the timing of the first ANC visit. However, some health-provider factors are associated with the timing of the first ANC visit. Women who indicated satisfaction with the friendliness of their health providers were significantly more likely to make their first ANC visit in the first trimester than later (b = 161; OR = 1.17). However, this effect vanished with the introduction of control variables in the final model. Also, highly educated (b = 0.960; OR = 2.6) and wealthy (b = 0.867; OR = 2.4) women were significantly more likely to make their first ANC visit in the first trimester of pregnancy compared to uneducated and poorer women. In all these, the variance estimated at the household level, including null models were not significant. However, variance estimated at the EA level was significant, indicating that there are some unobserved factors at the EA level that may explain differences in the timing of the first ANC visit among women. Significant intraclass correlation for number and timing of ANC visits at the EA level were estimated at 0.7 and 14 %.

Discussions

Previous literature that compared private with public health facilities in developing countries, including those in sub-Saharan Africa, found significant differences across the two health delivery systems (Tuan et al. 2005; Basu et al. 2012; Waiswa 2015; Hsu 2010; Ozawa and Walker 2011). Differences between these two major health providers have often been traced to some indicators that help in the assessment of quality of care referred to as health-provider characteristics in this paper. Such health-provider characteristics have often influenced the perception that users of private health facilities have better health outcomes compared to users of public health facilities (see Montagu et al. 2011). Yet, to date research examining differences in antenatal health access and outcomes for private and public health facilities is extremely limited, especially in low-income countries. We fill this gap by first examining if significant differences exist between private and public health facilities in Ghanaian women’s access to antenatal health care. Second, we extend the debate by testing if the differences between private and public health facilities may be attributed to these health-provider factors or the socioeconomic characteristics of the users.

Results from the study demonstrate a difference between private and public health facilities regarding antenatal access for Ghanaian women. Users of private health facilities made more visits than users of public health facilities. However, no difference exists between the two on the timing of antenatal care. A study in the Gambia compared women’s antenatal experience in both private and public hospitals and concluded that users of public hospitals were generally less satisfied with the health care environment, wait-time, privacy, time spent with medical personnel, etc. (Jallow et al. 2012). Although not directly related to antenatal care, similar observations have been made for users of private and public health facilities in Ghana (Aikins and Ahmed 2014; Turkson 2009). It is possible, therefore, that the increased ANC visits for private health facility users may be due to these and other related factors. Our results demonstrate that such health-provider-related factors may be relevant. For instance, we found that women made more visits for ANC if they thought the health provider was friendly. However relevant, these health-provider factors did not explain why users of private health facilities made more ANC visits compared to women using public health facilities. The findings call into question perceptions of private health care as effective, and better than services delivered by the public health care system and underscores Basu et al.’s (2012) earlier observation that private health care may not be necessarily efficient and medically effective as is often portrayed. The finding is also consistent with a study in Uganda that found that private health facilities did not necessarily perform better than public health facilities regarding coverage of essential newborn care interventions (Waiswa et al. 2015).

Some literature found sharp socioeconomic differences between users of private and public health facilities (see Harris et al. 2011; Basu et al. 2012; Waiswa et al. 2015). Private health facilities are more accessible to the educated and wealthy due in part to their relatively high user fees and the fact that the wealthy can afford these services. Our findings corroborate this as the educated and wealthy are more likely to use private than public health facilities. On other hand, it has been made abundantly clear in Ghana and elsewhere that women in higher socioeconomic brackets make more ANC visits especially in the first trimester of their pregnancy than later (Banchani and Tenkorang 2014; Dixon et al. 2014; Asamoah et al. 2014). It is therefore possible that variations between private and public health facilities may reflect the selective differences between users of these facilities. Our results capture this reality especially as the inclusion of socioeconomic variables rendered differences between private and public health facilities nonsignificant.

Our findings demonstrate that differences in antenatal care between private and public health facilities in Ghana cannot be attributed necessarily to health-provider differences between the two, but rather differences in the socioeconomic characteristics of the users. It is the case that users of private health facilities comprise of the educated, who may be aware of the benefits of the timeliness of antenatal care, and the wealthy, who also may have the means to make the recommended number of visits.

The findings suggest continuous support for both private and public health sectors in the provision of health care and management of diseases for Ghanaian women. Although health-provider factors did not account for the differences between private and public health facilities, some health-provider characteristics proved useful in promoting ANC among Ghanaian women. For instance, women made more visits for ANC if they thought health care providers were friendly. It is important for health care providers to ensure that clients are treated with utmost respect and dignity including handling their cases with maximum privacy and confidentiality. Although the largest provider of health services to the Ghanaian populace, the public health delivery system is confronted with several challenges that often contribute to perceptions of inferiority of services among Ghanaians. This study, like some few others, does not support the conclusion that women attending private health facilities have improved antenatal health access compared to those attending public health facilities, and calls for continued research efforts in comparing other maternal health access and outcomes for the private and public health sectors in sub-Saharan Africa.

The study has several limitations worth mentioning. First, although there are different private and public health care providers in Ghana, the study did not capture these complex differences and lumped all private and public health care providers into the same group. It is possible that the different private and public health care providers may have differences in antenatal health access for their users. However, we could not tease out these differences mainly because of the smaller sample size for users of private health facilities. Second, it is possible that users of private hospitals also used public health facilities at some point and vice versa, but such complexities are not captured in this analysis partially because of the cross-sectional nature of the data. Besides, we are unable to draw causal connections between type of health facility and the outcome variables mainly due to the contemporaneous nature of the data. Also, the time order between outcome variables (timing and number of visits) and health-provider factors suggests that the former precedes the latter although the latter were used as predictor variables. Thus, we limit results of this paper to associations and refrain from making causal connections between predictor and outcome variables. Third, respondents used for analysis were limited to those who had attended the health facility for antenatal care in the last 6 months preceding the survey. This limited the sample size which in turn could affect statistical power and the chances of detecting statistical associations.

Notwithstanding, the study is relevant and makes substantial contributions to the literature on health systems and health care in sub-Saharan Africa and Ghana. There are currently very few studies that compare health outcomes for private and public health facilities in low- and middle-income countries, including those in sub-Saharan Africa. By examining antenatal health access for both private and public health facilities, this study fills an important gap and encourages further debates in this area of scholarship.

References

Adesanya, T., Gholahan, O., Ghannam, O., Miraldo, M., Patel, B., Verma, R., et al. (2012). Exploring the responsiveness of public and private hospitals in Lagos. Journal of Public Health Research, 1, e2.

Afulani, P. A. (2015). Rural/urban and socioeconomic differentials in quality of antenatal care in Ghana. PLoS One, 10(2), e0117996. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117996.

Agha, S., & Keating, J. (2009). Determinants of the choice of a private health facility for family planning services among the poor: Evidence from three countries private sector partnerships-One project. Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates Inc.

Aikins, I., & Ahmed, M. (2014). Assessing the role of quality service delivery in client choice for healthcare: A case of Bechem Government Hospital and Green Hill Hospital. European Journal of Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 2(3), 1–23.

Asamoah, B. O., Agardh, A., Pettersson, A. O., & Ostergren, P. (2014). Magnitude and trends of inequalities in antenatal care and delivery under skilled care among different socio-demographic groups in Ghana from 1988-2008. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 295.

Baffuor-Awuah, A., Mwini-Nyaledzigbor, P. P., & Richter, S. (2015). Enhancing focused antenatal care in Ghana: an exploration into perceptions of practicing midwives. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 2, 59–64.

Banchani, E., & Tenkorang, E. Y. (2014). Occupational types and antenatal care attendance among women in Ghana. Health Care for Women International, 35(7–9), 1040–1064.

Basu, S., Andrews, J., Kishore, S., Panjabi, R., & Stuckler, D. (2012). Comparative performance of private and public healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS Medicine, 9(6), 1–14.

Chaitkin, M., Schnure, M., Dickerson, D., & Alkenbrack, S. (2015). How Ghana can save lives and money: The benefits of financing family planning through national health insurance. Washington, DC: Futures Group, Health Policy Project.

Chama-Chiliba, C. M., & Koch, S. F. (2013). Utilization of focused antenatal care in Zambia: examining individual- and community-level factors using a multilevel analysis. Health Policy & Planning, 30(1), 78–87.

Dean, C., & Lawless, J. F. (1989). Tests for detecting over-dispersion in Poisson regression models. Journal of American Statistical Association, 84, 467–472.

Dixon, J., Tenkorang, E. Y., Luginaah, I. N., Kuuire, V. Z., & Boateng, G. O. (2014). National health insurance scheme and antenatal care in Ghana: Is there a relationship? Tropical Medicine & International Health, 19(1), 98–106.

Gaddah, M. & Munro, A. (2011). The progressivity of health care services in Ghana. GRIPS Discussion Paper 11–14. GRIPS Policy Research Center, Tokyo.

Ganle, J. K. (2015). Ethnic disparities in utilization of maternal health care services in Ghana: evidence from the 2007 Ghana Maternal Health Survey. Ethnicity & Health, 21(1), 85–101.

Ghana Development Planning Commission. (2015). Ghana Millennium Development Goals: 2015 Report. http://www.gh.undp.org/content/dam/ghana/docs/Doc/Inclgro/UNDP_GH_2015%20Ghana%20MDGs%20Report.pdf.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF International. (2015). Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Rockville, MD: GSS, GHS, and ICF International.

Guo, G., & Zhao, H. (2000). Multilevel modeling for binary data. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 441–462.

Harris, B., Goudge, J., Ataguba, J. E., McIntyre, D., Nxumalo, N., Jikwana, S., & Chersich, M. (2011). Inequities in access to health care in South Africa. Journal of Public Health Policy, 32, s102–s123.

Hera-Health Partners Ghana. (2013). Evaluation of the free maternal health care initiative in Ghana. Volume I (Main Report). http://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/Ghana_130517_Final_Report.pdf

Hsu, J. (2010). The relative efficiency of public and private service delivery. World Health Report: Background Paper, 39. Geneva: WHO.

Hutchinson, P. L., & Agha, S. (2011). Measuring client satisfaction and the quality of family planning services: A comparative analysis of public and private health facilities in Tanzania, Kenya and Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 11, 203.

Jallow, I. K., Chou, Y., Liu, T., & Huang, N. (2012). Women’s perceptions of antenatal care services in public and private clinics in the Gambia. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 24(6), 595–600.

Lawless, J. F. (1987). Negative binomial and mixed Poisson regression. The Canadian Journal of Statistics, 15, 209–225.

Lewis, M. (2006). Government and corruption in public health systems. Working paper no. 78. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Lincetto, O., Mothebesoane-Anoh, S., Gomez, P., & Munjanja, S. P. (2006). Antenatal care. In L. Joy & K. Kate (Eds.), Opportunities for Africa’s newborns: Practical data, policy and programmatic support for newborn care in Africa. Cape Town: PMNCH.

Markinen, M., Sealy S., Bitran, R.A., Adjei, S. & Munoz, R. (2011). Private health sector assessment in Ghana. World Bank Working Paper Series No. 210.

Montagu, D. D., Anglemyer, A., Tiwari, M., Drasser, K., Rutherford, G. W., Horvath, T., et al. (2011). Private versus public strategies for health service provision for improving health outcomes in resource-limited settings. San Francisco, CA: Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco. ISBN 978-1-907345-18-0.

Mullahy, J. (1986). Specification and testing of some modified count data models. Journal of Econometrics, 33, 341–365.

Nketiah-Amponsah, E., & Hiemenz, U. (2009). Determinants of consumer satisfaction of health care in Ghana: Does choice of health care provider matter? Global Journal of Health Science, 1(2), 50–61.

Obuobi, A. A., Pappoe, M., Ofosu-Amaah, S. & Boni, D. Y. (1999). Private health care provision in Greater Accra Region of Ghana. Small Applied Research Paper 8. Partnership for Health Research, Harvard School of Public Health.

Olusanya, B. O., Roberts, A. A., Olufunlayo, T. F., & Inem, V. A. (2010). Preference for private hospital-based maternity services in inner-city Lagos, Nigeria: An observational study. Health Policy, 96, 210–216.

Opoku, E. A. (2009). Utilization of Maternal Care services in Ghana by Region after the Implementation of the Free Maternal Care Policy, Fort Worth, TX: University of North Texas Health Science Center. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.hsc.unt.edu/theses/78.

Ozawa, S., & Walker, D. G. (2011). Comparison of trust in public vs private health care providers in rural Cambodia. Health Policy and Planning, 26, 120–129.

Pebley, A. R., Goldman, N., & Rodriguez, G. (1996). Prenatal and delivery care childhood immunization in Guatemala: do family and community matter? Demography, 33, 231–247.

Pell, C., Menaca, A., Were, F., Afrah, N. A., Chatio, S., Manda-Taylor, L., et al. (2013). Factors Affecting Antenatal Care Attendance: Results from Qualitative Studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PLoS One, 8(1), e53747. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053747.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Regidor, E., Martinez, D., Calle, M. E., Astasio, P., Ortega, P., & Dominguez, V. (2008). Socioeconomic patterns in the use of public and private health services and equity in health care. BMC Health Services Research, 8, 183. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-183.

Salisu, A., & Prinz, V. (2009). Health Care in Ghana. Report for the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation. https://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/90_1236873017_accord-healthcare-in-ghana-20090312.pdf.

Tuan, T., Dung, V., Nue, I., & Dibley, M. J. (2005). Comparative quality of private and public health services in rural Vietnam. Health Policy & Planning, 20(5), 319–327.

Turkson, P. K. (2009). Perceived quality of healthcare delivery in a rural district of Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal, 43(2), 65–70.

United Nations. (2011). MDG Acceleration framework: operational note. Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Poverty%20Reduction/MDG%20Strategies/MAF%20Operational%20Note.pdf.

Victoria, C. G., Matijasevich, A., Silveira, M. F., Santos, I. S., Barros, A. J. D., & Barros, F. C. (2009). Socio-economic and ethnic group inequities in antenatal care quality in the public and private sector in Brazil. Health Policy & Planning, 25, 253–261.

Waiswa, P., Akuze, J., Peterson, S., Kerber, K., Tetui, M., Forsberg, B. C., et al. (2015). Differences in essential newborn care at birth between private and public health facilities in eastern Uganda. Global Health Action, 8, 24251. doi:10.3402/gha.v8.24251.

Wilunda, C., Quaglio, G., Putoto, G., Takahashi, R., Calia, F., Abebe, D., et al. (2015). Determinants of utilization of antenatal care and skilled birth attendant at delivery in South West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Reproductive Health, 12, 74. doi:10.1186/s12978-015-0067-y.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tenkorang, E.Y. Type of Health Facility and Utilization of Antenatal Care Services Among Ghanaian Women. Popul Res Policy Rev 35, 631–650 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9406-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9406-0