Abstract

Growing attention to police shootings of unarmed citizens has provoked important discussions surrounding use of police force. While an emerging literature explores perceptions of those victimized by police, less is known about White Americans’ opinions towards the institution of policing. Drawing from stereotyping and dehumanization literatures, do Whites’ attitudes towards police vary based on the identity of a victim? And does the news of any police shooting influence Whites’ attitudes about police? Across two survey experiments, participants read a news story describing police killing an innocent victim and report subsequent attitudes towards police. We find that Whites’ views of police remain relatively neutral, on average, in response to news of a fatal police shooting. Our findings suggest that protest mobilization adjacent to police brutality may mask an underlying neutrality in opinions about policing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The targeting and killing of unarmed Black people has become a focal point for news cycles and activist organizations alike over the past decade and are indicative of a long, fraught relationship between communities of color and police (Hinton, 2021; Soss & Weaver, 2017). This tension boiled over in the summer of 2020, as millions of protestors took to the streets across the country to demand justice for Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Jacob Blake, among numerous other Black people killed or maimed by police.Footnote 1 Yet, even amidst the seemingly widespread and multi-racial momentum behind these protests and the Black Lives Matter Movement (BLM), there are stark differences in the perceptions that Americans hold about police. For instance, Pew data from early-2020 showed that Black respondents were significantly less likely than White respondents to have confidence that police were acting in the public’s best interest.Footnote 2

Academics have begun to take note of this discrepancy, as well as the relationship between police use of force and race more broadly. This includes the political implications of policing and incarceration (Burch, 2013; Walker, 2020; White, 2019), the processes by which perspectives about police emerge (Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek 2020; Weaver, Prowse, and Piston 2020), and the implications of exposure to news of police violence (Boudreau et al., 2019; Desmond et al., 2016; Israel-Trummel & Streeter, 2022; McGowen & Wylie, 2020). This work complements long-standing evidence linking Black people to perceptions of criminality, violence, and hostility (Dixon & Linz, 2000; Entman, 1997; Gilens, 2009; Gilliam and Iyengar 2000; Mendelberg, 1997; Yadon, 2022), the result of which is increased punitiveness. Indeed, prejudice towards Black people (Dixon, 2006; Peffley, Hurwitz and Sniderman 1997), interaction with Black people (Quillian & Pager, 2001; Gilliam, Valentino and Beckmann 2002), and the implicit dehumanization of Black people (Goff et al., 2008; Jardina & Piston, 2016; Moore n.d.) all have implications for the degree of punishment prescribed to Black suspects accused of committing crimes. These bodies of work underscore the troubling relationship between communities of color and policing, while highlighting that the perceived deservingness of police violence is linked with the racial identity of those involved.

Less is known, however, about how the identity of a police violence victim influences perceptions of police themselves. Does a White victim of police violence engender a harsher reproach for police among White Americans than police violence against a Black victim? A body of work on race, stereotypes, and public opinion demonstrates that White Americans tend to hold more punitive attitudes toward Black Americans (Dixon, 2006; Peffley, Hurwitz and Sniderman 1997; Carter & Corra, 2016). This aligns with a growing literature on the dehumanization of Black people relative to Whites (Goff et al., 2008; Jardina & Piston, 2021; Moore n.d.). This suggests that White people may have stronger negative reactions to non-Black victims of police shootings when compared to Black victims. In contrast to this, another literature has found that while attitudes toward victims of police violence or police themselves are malleable among non-White Americans, there is a pattern of stable perceptions of police among White Americans (Boudreau et al., 2019; Kaminski & Jefferis, 1998; McGowen & Wylie, 2020; Weitzer, 2002). This literature suggests that White people do not have strong emotional reactions nor shifts in opinion in response to news of police shootings. Thus, it may be that their attitudes towards police, policing, and victims of police shootings remain unchanged regardless of the victim’s identity.

To adjudicate between these competing expectations, we turn to two survey experiments. In both studies, White participants read a news article that describes an incident in which a Black man, White man, or an animal was killed by police. Alternatively, respondents in a control condition read about police in the context of school crossing guards. We subsequently measure attitudes towards police and related policy preferences, comparing the reactions of White Americans across these four conditions. Our results highlight two important points: (1) Whites’ perceptions of police are largely not conditional on the identity of the victim as Black or White, nor human or canine; however, (2) asking White people to read about police violence does influence their perceptions about police. While this second point represents a separate but related research question – whether exposure to a police shooting versus a more neutral control condition changes attitudes towards police at all – we take care to address it to provide greater context for our findings. For example, in terms of overall job approval of police, there is no substantive distinction in White participants’ reaction to news of a police shooting when conditioning on the victim’s identity. Yet compared to those who read the control condition, job approval decreases from being somewhat positive to neutral.

Taken together, these findings indicate that news of police violence can shift Whites’ perceptions of policing and police. However, conditional on reading news of a police shooting, these opinions are not influenced by the victim’s identity. This stands in contrast to literature which has found that, in other circumstances and experiments, White political behavior remains largely unaltered in response to police violence (Boudreau et al., 2019; Kaminski & Jefferis, 1998; McGowen & Wylie, 2020; Walker, Collingwood, and Bunyasi 2020; Weitzer, 2002). Our inclusion of victim identity provides additional nuance to this literature by accounting for how this dimension does or does not further impact public opinion. Indeed, the victim that most often influences views towards police among White participants is the canine victim. Importantly, we also add to a literature that examines perceptions of victims by incorporating reactions to the institution of policing. That is, we make an important distinction in this study between perceptions of the individual – for example, how deserving they are of punishment or recompense – and the institution of policing itself. This paper adds theoretical nuance by differentiating between these two components and examining the attitudes of White people in the face of information regarding police shootings. And while large-scale protest mobilization adjacent to policing and police violence may suggest malleable positions on these issues, our conclusions offer caution that White attitudes about police and policing are relatively neutral in the face of police violence.

Theory and Hypotheses

We begin by synthesizing the two primary bodies of literature that serve as a foundation for understanding whether the identity of a police shooting victim influences attitudes. The first literature we explore involves race and public opinion, noting a consistent association between Blackness and criminality, as well as the dehumanization of Black people. In contrast, another literature shows that White Americans remain relatively unmoved in their views of police or police brutality victims. This is not true of other racial groups; non-White people are more likely to have strong reactions to victims of police violence or towards police themselves in the wake of police violence. Below, we expand on each of these literatures and how they inform our competing expectations of attitudinal change versus stability among Whites when exposed to news of police violence.

Racial Stereotyping, Dehumanization, and Punitiveness

One reason to expect that attitudes would vary in the face of news of police shootings — and specifically vary based on the identity of the victim — can be drawn from literatures related to race, stereotypes, and public opinion. The relationship between Black Americans and the U.S. criminal justice system is long, complex, and fraught with tension. This comes not only from how police and the penal system have historically been used as oppressive and coercive forces in Black communities. It is also due to long-standing biases that connect Black people and criminality. A well-established literature has identified this distorted relationship, reinforced over time, between Blackness and crime (e.g., Barkan & Cohn, 2005; Chiricos et al., 2004; Entman, 1997; Gilliam and Iyengar 2000; Gilliam, Valentino, and Beckmann 2002; Peffley, Hurwitz, and Sniderman 1997; Quillian & Pager, 2001), as well as the disproportionate interactions that Black Americans have with the U.S. criminal justice system (Alexander 2010).

The news media is the predominant reinforcement mechanism of this relationship between Black Americans and criminality. They are not just frequently described as violent or engaged in criminal activity in the media, but the framing of news stories serves to reinforce this association. For example, Black Americans are more often shown in police custody or with a mugshot. They are overrepresented as “lawbreakers,” and they are more likely to be portrayed as criminals in the media than White people (Dixon & Linz, 2000). Further, Black people are a common subject matter in the news when it comes to criminal activity and violent behavior, and news stories also tend to take on White perspectives that emphasize White victimization (Entman, 1997). These racial cues and racially-coded language, both words and images, have downstream impacts on Whites’ political attitudes and policy preferences (Bennett & Walker, 2018; Gilens, 2009; Hutchings, Walton, and Benjamin 2010; Mendelberg, 1997; Valentino, Hutchings, and White 2002). For example, evidence suggests that Whites express more punitive attitudes after viewing a story about a Black murder suspect than a White murder suspect (Gilliam and Iyengar 2000). As another example, the racial composition of a BLM protest impacts perceptions of threat among White people. BLM protests depicted as comprised of only Black protestors are judged most likely to result in violence (Peay & Camarillo, 2021).

Furthermore, a growing body of evidence suggests that White people regard Black people not only as criminal but also as less than human (e.g., Goff et al., 2008). Goff and colleagues find evidence of the implicit dehumanization of Black people and find that priming dehumanization in White respondents leads to greater support for the use of violent police force against a Black suspect. Moreover, their content analysis of news coverage of Black and White death row inmates finds that Black inmates are frequently described using more animalistic and ape-like language (Goff et al., 2008). Other evidence highlights that White people who hold explicitly dehumanizing attitudes are more supportive of policies like three-strike laws, stop-and-frisk, and the death penalty (Jardina & Piston, 2016). This suggests that dehumanization is one contributing factor for levying stiffer punishments and harsher force against Black suspects (Goff et al., 2008; Eberhardt et al., 2004; Hutchings 2010; Jardina & Piston, 2016; Peffley & Hurwitz, 2007).

This work informs our expectation that White respondents may not exhibit as much backlash in attitudes towards police after receiving news of a Black police shooting victim relative to a non-Black victim. Consequently, it is plausible that (H1) White Americans may express less negative attitudes towards police following the killing of a Black victim compared to a White victim or canine victim. This expectation also aligns with dehumanization research demonstrating that Black people are subject to perceptions of inferiority (Goff et al., 2008; Jardina & Piston, 2021; Moore n.d). Thus, attitudes about police and policing may vary based on the race of a victim of fatal police violence.

Canines in Politics, Policing, and Police Violence

Humans are not the only victims of police violence, and canines shot during human encounters with police have been the subject of outrage and lawsuits across the country.Footnote 3 Just as efforts have been made in recent years to track police killings of civilians across the U.S., efforts have also been undertaken to compile information about animals killed by police (Bloch and Martinez 2020). For example, the Puppycide Database ProjectFootnote 4 has recorded over 2000 incidents of animals killed by police since 1990. The work to record, preserve, and disseminate this data reflects a wider area of study that concerns the relationship between humans and pets in several domains. For example, this effort underscores the empathy that dogs evoke within humans. Recent evidence highlights that when participants were asked to note their empathy for either human or canine victims of a violent assault – which varied portrayal of the victim as an infant, adult, a puppy, or 6-year-old dog – the greatest empathy was expressed for the infant followed by the puppy (Levin et al., 2017). Importantly for our purposes, the 6-year-old dog victim garnered a greater level of empathy in comparison to the adult human victim. These findings are echoed in other work, where the amount of empathy expressed towards puppies is on par with that expressed toward human babies or children (Angantyr, Eklund, and Hansen 2015).

Animals, and specifically pet dogs, can also become political. For example, a growing literature shows that pets provide insight into the character, steadiness, and trustworthiness of the political figures who own them (Atkinson et al., 2014; Jacobsmeier & Lewis, 2013; Maltzman et al., 2012; Mutz, 2010). But the reverence and deference given to these animals can also stand as a political talking point. For example, Justin Jones, a BLM activist in Tennessee, drew a comparison between Tennessee Governor Bill Lee’s attendance at an event designating the blue tick coonhound as the state’s official dog and Lee’s refusal to engage with discussion surrounding Medicaid Expansion in the state. On August 22, 2019, Jones tweeted:

I love dogs. A lot. But please explain the white privilege of @GovBillLee having more compassion for blue tick coonhounds than for the people in our state who are poor (denied Medicaid Expansion) or Black & Brown (attacked by his racist voter suppression & undermining of public ed).

In his tweet, Jones implies a sentiment of dehumanization surrounding disadvantaged people such that their needs and well-being are of less concern to a governor than a photo opportunity with an animal.

Drawing from these literatures and real-world examples, we not only compare human victims of police violence, but also place these in contrast with a canine victim. The inclusion of this condition is not a direct measure of dehumanization. It does, however, reflect the importance placed on animals in politics and the language that some activists have used in asserting that greater value is placed on canine lives in comparison to human lives. Therefore, in contrast to H1, this literature suggests that (H2) White people may express less negative attitudes towards police following the killing of a Black victim compared to reading about a canine victim.

White Apathy in the Face of Police Violence

Many studies have noted the significant behavioral impact of police shootings on American politics. While exploring the circumstances that lead to police stops and shootings (Mummolo, 2018; Streeter, 2019), this literature has established that these events can shift how and whether citizens engage in political activity (Enos, Kaufman, and Sands 2019; Williamson et al., 2018) and with the state itself (Desmond et al., 2016; Weaver, Prowse, and Piston 2020). What is especially notable is the powerful influence of one’s racial identity on reactions to police violence (Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek 2020; McGowen & Wylie, 2020; Peffley and Hurwitz 2007; Weitzer, 2002). In contrast to our previous hypotheses, this leads us to expect that Whites’ views of police in the wake of a police shooting will not be conditional on the identity of the victim.

A growing literature underscores striking differences in how Black and White Americans respond to and perceive policing and police violence. By and large, this literature suggests that while Black Americans hold more negative views of police or the criminal justice system in the wake of incidents of police violence, Whites are largely unwavering in their views (Boudreau et al., 2019; Hurwitz and Peffley 2007; Kaminski & Jefferis, 1998; Weitzer, 2002). For example, White survey participants are more likely than Black Americans to agree that the criminal justice and court systems treat people fairly (Hurwitz and Peffley 2007). Further, while a televised instance of a violent arrest of a Black man in Cincinnati, Ohio shifted non-White residents’ perceptions of police — specifically their perceptions of police use of force as unjust — White residents’ perceptions remained unchanged (Kaminski & Jefferis, 1998). Another study finds no meaningful effect of police misconduct on public opinion as measured via newspaper polls in New York City and Los Angeles among Whites. Being a person of color, therefore, is an important factor in the magnitude and longevity of decreased feelings of warmth toward police (Weitzer, 2002). In contrast, White public opinion is largely unaffected in the aftermath of police violence.

Racial identity appears to drive these differential responses due to emotional reactions and styles of information-processing that occur among the perceiver (Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek 2020; Phoenix, 2019). While African-Americans are more likely to express anger in response to a police shooting and place blame on police officers for the shooting, the same is not true for Whites (McGowen & Wylie, 2020). In experimental contexts, Black respondents express greater anger in response to police shootings (regardless of the victim’s identity), but Whites are more likely to report no emotional reaction when presented with a Black victim than when they are presented with a White victim (McGowen & Wylie, 2020). Other experimental work has highlighted these racial differences in response to police violence and suggests that racial identity influences how people perceive and process this information due to previously-held beliefs (Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek 2020). These authors argue that while neither racial group attachment nor prior beliefs about police can alone account for the stark discrepancies in reactions to police violence news, the interactive impact of these elements reflects distinct positionalities in the world.

Together, these studies have established that race-based differences in perceptions of policing and police violence exist. These findings are important for our purposes because they highlight that White Americans’ views are stagnant in many instances even after exposure to new instances of police violence. As a result, we might not expect Whites’ views to change significantly based on the victim’s identity. That is, (H3) White Americans’ views towards police will not be conditional on the victim’s identity. White Americans’ views towards victims of police violence are not impacted in other contexts, so it is plausible that this holds true with respect to opinions about police or the institution of policing as well.

Experimental Design and Methods

To test these competing hypotheses, we designed a survey experiment that relies on fictional, but realistic, news stories regarding a fatal police shooting. As discussed in further detail below, the first study was conducted with White participants in 2018 on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) and had two treatment conditions: a Black male victim and a canine victim. Our second MTurk study with White participants in 2019 incorporated a third treatment condition — a White male victim — as an additional point of comparison.Footnote 5

The treatment conditions described a fictional police shooting. Even though the specific instance of police violence described in the treatment conditions was fictional, the language used within the articles is drawn from actual events to provide an accurate portrayal of discussions of police violence.Footnote 6 The treatments reflect real-world reporting on police killings in several crucial ways. First, the articles themselves are based on the reporting of actual police shootings. For example, we drew on a 2016 incident in which Charles Kelsey, lying on his back with his hands raised in the air after attempting to assist another man at the scene, was shot and injured by police in North Miami, Florida. This incident was caught on film, and, similarly, the stories developed for this study also reference video-footage capturing the incident.

To test our hypotheses, we compare across treatment conditions to understand how the victim’s identity may condition reactions towards police. We also include a control condition which allows for a secondary examination of whether any news of a police shooting influences Whites’ perceptions of police. In the control condition, participants read a story about a search for crossing guards for a school district. The story briefly mentions police participating in the training process, and there is no mention of race or violence in the control.

The survey showed participants the approximately 360-word news story for 30 seconds before allowing them to proceed. The average time participants spent on the page with the news story in each study was 90 seconds. The length and construction of the article, including a photo and descriptive headline, along with the period of time which it was viewed by participants reflects the reality of news consumption. These conditions are comparable to the situations in which a similar story would be viewed on local news or on social media platforms.

Importantly, the key information regarding the shooting remained relatively constant across the treatments with efforts made to minimize changes in language used. We highlight these changes in Table 1 and provide the treatments as they were presented to respondents in Appendices 2 and 3. This language was crafted to portray all victims as innocent and inculpable for the shooting. That is, the dog was depicted as not being aggressive, but as barking at the police officer as he walked by the dog’s yard. The male victims are depicted as leaving home to walk to a nearby convenience store for a snack when they are approached by an officer. It is reported that the men raise their arms in the air to make clear they are not a threat as they walk away. The decision to explicitly state the victim’s innocence was purposeful. It represents a tradeoff between representing complex real-world scenarios and being able to confidently conclude that the victim’s identity is the primary thing influencing differences between treatments. Many incidents of police violence are subject to debate in the media and in the criminal justice system, including those circumstances under which force is used. Incorporating this situational uncertainty into our treatment conditions would allow respondents to impute their own information to fill gaps in the provided story. In turn, this might lead respondents to infer guilt in some conditions and not in others (Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek 2020). While this would be valuable to test in future studies, we decided to draw from the subset of police involved shootings in the real-world that clearly indicate the victim was innocent and the officer at fault.

The photos depicting the male victims were drawn from the Chicago Face Database (Ma et al., 2015). The photos of the Black and White men were selected given their ratings on different attributes, specifically attractiveness, perceived threateningness, and racial prototypicality.Footnote 7 The photo of the dog was selected after consideration of the coloration, breed, age, and other photo qualities (i.e., with or without eye contact, objects shown in the background). We opted for a photo including a grassy background, with an appearance that was not clearly old or puppy-like.

In the first MTurk study, we recruited 298 White participants between August 10–11, 2018. In the second, we recruited 802 White participants between January 26–28, 2019.Footnote 8,Footnote 9 After exposure to the randomized news story,Footnote 10 participants were asked a series of questions related to their perceptions of the events referenced in the article and their attitudes towards police more broadly. These included questions regarding approval of how police are doing their job and a battery of items developed to assess views towards police. These items asked, for example, whether police abuse their power, are honest about their actions, hold racist views, and face harsh enough consequences for killing unarmed citizens. These items contribute to understanding how views of police as an institution may change in the wake of news about police killing an innocent civilian.

Results

For the analyses presented below, variables are coded from zero to one and all statistical tests presented are two-tailed. We present the analyses from our 2018 and 2019 studies side-by-side given their parallel design and shared question wording. Recall that our primary research question of interest asks whether the identity of the victim of a police shooting influences Whites’ reactions towards police — measured through job approval, perceptions of police misconduct, and perceptions of police behavior. Throughout the analyses presented, we examine the main effects of our treatments on participants’ views. First, we consider outcomes when only comparing among the treatment conditions, using the Black victim condition as the baseline. Then, we discuss the analyses comparing the treatment conditions to the control – i.e., the non-violent news story – in the second section.

Are Whites’ Attitudes Towards Police Conditional on the Victim’s Identity?

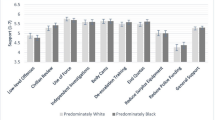

To begin, we examine whether and how job approval of police varies based on the victim of a police shooting (Fig. 1). Importantly, we find no statistical or substantive difference in either of our studies in terms of participants approval of police, regardless of who is portrayed as being killed by police. This includes when comparing by race and when comparing human versus canine victims. Consistent with other work that has found a relative lack of reaction to policing and police violence among White Americans (Boudreau et al., 2019; McGowen & Wylie, 2020; Kaminski & Jefferis, 1998; Walker, Collingwood, and Bunyasi 2020; Weitzer, 2002), this provides some additional evidence that White opinions about policing remain unchanged after reading about police violence.

Next, we turn to the other variables examining attitudes towards policing. Specifically, we asked the following questions: “Do you think incidents of police brutality are common?”; “How common do you think racist feelings are among police officers?” A third item asked respondents how much they agreed with the assertion that it is “rare for police officers to abuse their power.”

When comparing the treatment conditions, we find no differentiation in White respondents’ reactions to news of a police shooting of a canine victim compared to a Black victim in the 2018 study (Fig. 2). In the 2019 study, however, we find that when the victim of a police shooting is depicted as a family dog, participants are approximately five percentage points more likely to believe that police brutality is common compared to those viewing a Black victim (p < 0.06). In contrast, there are no differences between the Black and White victims in terms of the perceived regularity of police brutality. Taken together, participants’ views on police brutality are largely unchanged in the face of a police shooting. The only suggestion that brutality may be perceived as being more common after reading about a police shooting comes when a canine is depicted as having been the victim.

Next, we examine perceptions that racist feelings are common among police. Here, too, we find a similar effect on reactions to viewing the canine victim in the 2019 study (Fig. 2). Whites who see that condition are approximately five percentage points more likely to say that police officers hold racist feelings compared to those who saw a Black victim (p < 0.09). Interestingly, participants in the 2019 study are also five percentage points more likely to say that police hold racist feelings when the victim is White as opposed to Black (p < 0.08). Overall in our 2019 study, we find that perceptions of officers being racist increases when the victim is not Black. Still, the general sentiment among participants is that racist feelings are neither common nor uncommon among police—moving from about 0.52 on a 0–1 scale in the Black victim condition, compared to about 0.57 in either the White or dog victim conditions. Again, this highlights a consistency – and general neutrality – in views of police as opposed to strong backlash effects when reading about different victims of police violence.

The last item in this section asks respondents how much they agree that police officers rarely abuse their power. In both studies, when testing our central hypotheses that compare across treatment conditions, there is no evidence that the identity of the victim changes Whites’ perceptions about the frequency with which police officers abuse their power. Consistent with the other findings in this section, then, there are no discernible differences across the treatments themselves on perceptions of police abuse of power.

Taken together, the evidence from this set of dependent variables underscores that there is little distinction made in Whites’ opinions of police conditional on the victim’s identity. When comparing across treatment conditions, White participants’ views towards police are neutral and statistically indistinguishable, regardless of who is depicted as the victim of a police shooting. There is some evidence that viewing the canine victim compared to the Black victim results in slight increases in beliefs that police brutality is common or that police harbor racist feelings. On the whole, though, each of the point estimates across conditions and dependent variables in this section hovers around the mid-point of the variable’s scale (see Appendix 4). In other words, White participants remain neutral in their views of police and police behavior, regardless of whether the innocent victim is human or canine.

Finally, our last set of dependent variables further interrogates attitudes towards police and their behavior. These questions ask White participants to what degree they agreed with the following statements: “Police only use their gun when necessary;” “Police officers give honest explanations for their actions;” and, “Police officers don’t face harsh enough consequences when they kill an unarmed citizen.”

As shown in Fig. 3, when comparing only among the treatment conditions, the identity of a victim does not influence White participants’ perceptions that police only use their gun when necessary or that they give honest explanations for their answers. In both studies, participants are equally likely to believe that police use their gun when necessary in all treatment conditions. Similarly, these participants are equally likely to believe that police are honest in explaining their actions. Like the patterns noted with the previous set of dependent variables, participants who read about any victim of a police shooting are relatively neutral in their views of police on both of these items. Indeed, the point estimates hover around 0.50 on a 0–1 scale in every treatment condition in both studies. Thus, there is no substantive or statistically meaningful difference in reaction conditional on the victim’s identity.

The final item examines whether White participants believe police face appropriate consequences for their actions. Here, too, we do not detect any significant differences in views when comparing across the treatment conditions (Fig. 3). We again find steady perceptions of police behavior, given that participants read about an unjustified police shooting. Interestingly, this is the only item on which levels of agreement are consistently above the mid-point of the 0–1 scale. Participants in both studies are closer to saying they “somewhat agree” that police officers do not face harsh enough consequences, on average, rather than taking a neutral position on the statement. Still, Whites’ perceptions of whether police officers face harsh enough consequences for killing unarmed individuals are not conditional on the identity of the victim.

Among those who read about a police shooting, Whites’ perceptions of police behavior and the corresponding consequences of misbehavior change very little. Across each of the domains examined, we consistently fail to find any meaningful differences in the views that White participants held towards police after reading about a police shooting, regardless of the victim’s identity.

Do Whites’ Attitudes Towards Police Change Relative to the Control?

As discussed throughout the prior sections, our main research question focuses on whether or how White Americans’ views towards police change conditional on the victim’s identity. Still, the inclusion of a control condition in our studies provides an opportunity to examine perceptions of police in the absence of police violence. The control condition allows us to distinguish between how news of police violence impacts White perceptions of police and how changing the identity of the victim might further alter these opinions, as described above. In this section, we reanalyze our data using the control condition as the baseline. Our findings across all items for these analyses can be found in Appendix Tables 4C and 4D.

To begin, we look at job approval. In both the 2018 and 2019 studies, job approval of police decreases in response to news of a police shooting relative to the control condition. Here, we do find consistent evidence of an effect. There is between a 13 and 17 percentage point decrease in evaluations of police depending on the condition. This effectively moves respondents from a slightly positive sense of police job approval to feeling relatively neutral, on average. For example, in the 2019 study job approval moves from about 0.65 on a 0–1 scale in the control to just above or below 0.50 in each treatment (p < 0.01). Thus, we find evidence that news of a police shooting lowers job approval of police, but importantly, it does not lead to negative views of police among Whites.

Next, we return to the items that measured attitudes about police – i.e., the beliefs that police brutality is common, that racist feelings are common among police, and that police rarely abuse their power. The most consistent pattern of findings emerges when comparing the dog victim to the control for each of these outcomes. For example, for those who read about a canine victim relative to the control, we find that the belief that police brutality is common increases nine percentage points in the 2018 study and seven percentage points in the 2019 study (p < 0.05; p < 0.05). In contrast, the Black male victim only increased these perceptions in the 2018 study (p < 0.05) and the White male victim did not move perceptions. With respect to the other two dependent variables in this set—i.e., beliefs that racist feelings are common and that police are likely to abuse their power—we find a similar pattern of results. In each case, it is only the canine victim condition that is statistically significant relative to the control. In sum, this pattern suggests that Whites’ opinions can move in response to news of a police shooting when placed in comparison to a news story that does not mention police violence. This is most consistent when reading about a canine victim.

Finally, we turn to the items that consider attitudes about police behavior – i.e., the beliefs that police only use their gun when necessary, give honest explanations, and do not receive harsh enough consequences for their actions. Unlike the prior set of items, we more consistently find that news of any police shooting influences participants’ views on these items. Here, too, these changes are from being somewhat positive in the control to neutral in the treatment conditions. For example, in almost all treatment conditions across both studies, White participants are consistently less likely to agree that police only use their gun when necessary relative to those participants in the control condition. The 2019 Black victim condition is the only place where this is not the case. We find a similar pattern when we consider respondents’ perceptions that police give honest explanations for their actions. In all treatment conditions, respondents are less likely to believe that police give honest explanations for their actions in comparison to the control condition. Even though news of police violence does shift attitudes about police honesty from slightly positive to neutral, recall from the last section that these attitudes are not conditional on the victim’s identity. For both police use of guns and police honesty, we find similar patterns to what we encountered before: those in the control had positive perceptions of police, while those in the treatment conditions are neutral (i.e., near the mid-point of our 0–1 scale). Thus, while news of police shooting an innocent victim does shift Whites’ perspectives, it does not leave a negative view of police behavior.

An exception comes when we consider whether police face appropriate consequences for their actions. Even after reading about police misconduct and an innocent victim being killed, we do not find any treatment effects in our 2019 study. Put differently, Whites are equally likely to say that police do not face appropriate consequences for their actions in the treatments relative to the control. However, participants in the 2018 study are about seven percentage points more likely to believe police officers do not face harsh enough consequences for their actions after reading about a canine being shot by police relative to the control (p < 0.10), but not a Black victim. Again, these attitudinal shifts when comparing the control to the treatments are only indicative of changes from somewhat positive perceptions of police to neutral ones—and only when comparing the canine victim to the control.

In light of this, it is apparent that incorporating the control condition paints a somewhat more complex picture of policing and public opinion. In some cases, news of any police shooting decreases the positivity with which Whites view police. In other cases, only with certain victims—particularly the canine victim—do we find consistent patterns of opinion change. Substantively, these shifts do not represent a swing from positive to negative views of police when confronted with clear evidence of police wrongdoing, but rather they are the equivalent of “neither approving nor disapproving” of police behaviors. Together, this suggests that although Whites’ views towards police can shift in some cases, they remain relatively neutral overall.

Conclusion

Our work builds from scholarship that considers perceptions of police shooting victims and it extends this work by incorporating attitudes towards the institution of policing itself. This contribution is valuable because it encompasses both perceptions of individual police interactions, as well as broader views towards policing as an institution in the wake of police violence. This study uses two survey experiments to gauge attitudes toward police and policing by exposing participants to news of a police shooting targeting either a Black, White, or canine victim. Drawing from literatures in criminal justice, dehumanization, policing, and public opinion, we propose two competing sets of expectations. First, we suggest that associations between Black people and stereotypes of criminality and dehumanization mean that White Americans might express less backlash in their views of police after reading about a police shooting involving an innocent Black victim as opposed to a White victim or dog victim. Alternatively, a growing literature has noted that while the attitudes of Black or Hispanic Americans are malleable in the aftermath of police violence, White Americans display unwavering and often indifferent reactions to such incidents.

While our findings are generally consistent with this second set of literature such that we find little evidence that White Americans’ take a starkly negative turn after news of police shootings, we do see some measurable changes in opinions of policing when they read about police violence. Although there is evidence that White respondents may express less positive views of police in response to news of a police shooting compared to a control, their perceptions of police behavior and the corresponding consequences of misbehavior are far from overwhelmingly negative. Instead, we find shifts from slightly positive attitudes towards police and policing in the control condition to more neutral stances after exposure to news of police violence. Interestingly, when excluding the control and comparing just those who read news of a police shooting, the victim’s identity largely does not appear to condition participants’ responses. The exception to this pattern is that in two instances Whites are somewhat more likely to believe police brutality is common and that police are racist after reading about police killing a family dog as opposed to an innocent Black victim. Overall, then, the patterns across our two complementary sets of analyses reveal that Whites’ perceptions of policing are neutral, even in the wake of news of police violence.

Another interpretation of our findings may suggest cautious optimism for some readers about public opinion on policing in the aftermath of police violence. That is, even though White attitudes remain relatively neutral regarding police and policing overall, we see that they can shift in comparison to the control condition. That these perceptions of policing are not substantively different when comparing between the treatment conditions alone is perhaps notable. However, we do not believe that our findings imply that such optimism is warranted. For example, when placing our treatment conditions in comparison to the baseline, the Black victim condition yields the fewest shifts in perceptions across both studies. With the exception of job approval and the belief that police give honest explanations for their actions, we do not find significant differences between the Black victim condition and the control condition. Therefore, our findings should not be taken as an indication that racial identity is inconsequential to policing, police, nor to those who are impacted by or are witness to police violence. Indeed, there is ample research to suggest that race and identity impact other attitudes surrounding policing (e.g., Israel-Trummel & Streeter, 2022; Jefferson et al., 2020; Lerman and Weaver 2014; Ostfeld & Yadon, 2022).

Further, this work has important implications for thinking about protests in response to police brutality. In the summer of 2020, there was broad mobilization centered around police brutality and issues of racial injustice. The size and multi-racial composition of this national discussion and mobilization might imply that White attitudes towards police can be malleable. What underlies the protests may be murkier. The motivations of the crowds in the Summer of 2020 were not uniform, and research has found that a non-trivial percentage of these participants were present for reasons outside of BLM.Footnote 11 Similarly, the surge in activity is not necessarily undergirded by shifting White attitudes toward policing or even race. Though our experiments were conducted prior to 2020, they complement other work suggesting that attitudes in the domain of police, policing, and police brutality are deeply-seated. Thus, what might appear to be a momentous shift in attitude toward policing on the surface — operationalized by protest engagement — might actually mask anchored and unwavering public opinion among White Americans.Footnote 12

This topic certainly warrants greater study to more fully understand how attitudes towards police operate. It is possible that the wave of 2020 protests, in the wake of several fatal police shootings captured in devastating videos, may invoke greater outrage among White Americans that a single story cannot. For example, the viral video of George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police was thought to have spurred much of the protest activity in the summer of 2020. Our news article was brief, in contrast, and included a neutral image of the victim said to be drawn from social media. The disturbing nine-minute video and sustained news coverage of Floyd’s death rightfully occupied the minds, emotions, and news-feeds of Americans for weeks. In this regard, our evidence highlights that sharing a brief news story of a police-involved shooting is unlikely to make Whites’ attitudes towards police as an institution starkly negative. These findings suggest a pessimistic view of overall police accountability in the wake of civilian deaths at the hands of police.

This research also has important implications for how organizers and activists should approach mobilization around police brutality, defunding police, and police abolition. Our work indicates that such messaging or mobilization strategies directed towards White Americans will require care, strategy, and persistence if they are to shift views in a meaningful manner. The engagement of White Americans – or any ethnoracial group – is not necessarily indicative of shifting attitudes nor progressive opinions on police and policing. Scholars and activists should be wary of conflating the two. Understanding political reactions to the institution of policing and movement responses against police brutality are likely to continue to be of great importance to scholars and activists alike.

These studies expand our understanding of Americans’ reactions to news coverage of police shootings, while also connecting police use of force to race, crime, violence, dehumanization, and public opinion in the U.S. Ultimately, these findings highlight a concerning lack of empathy for human life in the context of fatal police shootings, whereby White respondents differentiate little, if at all, in their reactions to news of violence against a human victim in comparison to violence against an animal. Our findings suggest that perceptions of victim deservingness and the circumstances surrounding police violence may change, but White Americans’ opinions towards police remain relatively neutral in the face of news that an innocent civilian has been killed by police.

Notes

Buchanan, Larry, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel. “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History.” July 3, 2020. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html

Gilberstadt, Hannah. “A month before George Floyd’s death, black and white Americans differed sharply in confidence in the police.” June 5, 2020. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/05/a-month-before-george-floyds-death-black-and-white-americans-differed-sharply-in-confidence-in-the-police/

For example, see Salcedo, Andrea. “Body-cam footage shows police shoot a ‘playful’ puppy: He was curious and excited to greet this officer.” August 27, 2021. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/08/27/colorado-lawsuit-officer-shot-puppy/

Puppycide Database Project. https://puppycidedb.com/

Replication data and code are available at https://bit.ly/3ijmHwD.

Shapiro, Emily. “Unarmed Man With Hands Up Shot by Cop: There’s `No Justification,’ Lawyer Says.” July 21, 2016. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/unarmed-man-hands-shot-cop-justification-lawyer/story?id=40770046

For example, with respect to the Black and White male photos, both were rated as having one of the least threatening appearances in their respective race-gender subgroup, above average attractiveness, and above average prototypical characteristics. Further, the perceived threateningness was equivalent for both photos in the Chicago Face Database.

Consistent with other studies involving MTurk data (Berinsky, Huber, and Lenz 2012), our sample is distinct from a nationally representative sample in several ways (see Appendix Table 1 for detailed descriptives).

See Appendix 5 for a description of the power calculations.

We conducted a balance check across conditions with respect to gender, income, age, education, partisanship, and ideology. We find two instances in which there are slight imbalances with respect to income in the 2019 study. Those in either the dog or Black victim conditions have higher reported income ($50,000-$59,999) than those in the White victim condition ($40,000-$49,999; p < 0.05).

Gause, LaGina and Maneesh Arora. “Not All of Last Year’s Black Lives Matter Protesters Supported Black Lives Matter.” July 2, 2021. The Monkey Cage Blog. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/07/01/not-all-last-years-black-lives-matter-protesters-supported-black-lives-matter/

Chudy, Jennifer and Hakeem Jefferson. “Support for Black Lives Matter Surged Last Year. Did It Last?” May 21, 2021. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/22/opinion/blm-movement-protests-support.html.

References

Alexander, M. (2010). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press.

Angantyr, M., Eklund, J., & Hansen, E. M. (2015). A comparison of empathy for humans and empathy for animals. Anthrozoos, 24(4), 369–377.

Atkinson, M. D., Deam, M., & Uscinski, J. E. (2014). What’s a dog story worth? Political Science & Politics, 47(4), 819–823.

Barkan, S. E., & Cohn, S. F. (2005). Why whites favor spending more money to fight crime: The role of racial prejudice. Social Problems, 52(2), 300–314.

Bennett, D., & Walker, H. (2018). Cracking the Racial code: Black threat, white rights and the lexicon of American politics. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 77(3–4), 689–727.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon. com’s mechanical turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Bloch, S., & Martınez, D. E. (2020). Canicide by cop: A geographical analysis of canine killings by police in Los Angeles. Geoforum, 111, 142–154.

Boudreau, C., MacKenzie, S. A., & Simmons, D. J. (2019). Police violence and public perceptions: An experimental study of how information and endorsements affect support for law enforcement. The Journal of Politics, 81(3), 1101–1110.

Burch, T. (2013). Trading democracy for justice: Criminal convictions and the decline of neighborhood political participation. University of Chicago press.

Carter, J. S., & Corra, M. (2016). Racial resentment and attitudes toward the use of force by police: An over-time trend analysis. Sociological Inquiry, 86(4), 492–511.

Chiricos, T., Welch, K., & Gertz, M. (2004). Racial typification of crime and support for punitive measures. Criminology, 42(2), 358–390.

Desmond, M., Papachristos, A. V., & Kirk, D. S. (2016). Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 857–876.

Dixon, T. L. (2006). Psychological reactions to crime news portrayals of Black criminals: Understanding the moderating roles of prior news viewing and stereotype endorsement. Communication Monographs, 73(2), 162–187.

Dixon, T. L., & Linz, D. (2000). Race and the misrepresentation of victimization on local television news. Communication Research, 27(5), 547–573.

Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, V. J., & Davies, P. G. (2004). Seeing black: Race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 876.

Enos, R. D., Kaufman, A. R., & Sands, M. L. (2019). Can Violent Protest Change Local Policy Support? Evidence from the Aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles Riot. American Political Science Review., 113(4), 1012–1028.

Entman, R. M. (1997). “Modern racism and images of blacks in local television news” do the media govern? Politicians, Voters, and Reporters in America, 7(4), 283–286.

Gilliam, F. D., Jr., & Iyengar, S. (2000). Prime suspects: The influence of local television news on the viewing public. American Journal of Political Science., 44(3), 560–573.

Gilliam, F. D., Jr., Valentino, N. A., & Beckmann, M. N. (2002). Where you live and what you watch: The impact of racial proximity and local television news on attitudes about race and crime. Political Research Quarterly, 55(4), 755–780.

Gilens, M. (2009). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. University of Chicago Press.

Goff, P. A., Eberhardt, J. L., Williams, M. J., & Jackson, M. C. (2008). Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 292.

Goff, P. A., Jackson, M. C., Leone, Di., Lewis, B. A., Culotta, C. M., & DiTomasso, N. A. (2014). The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526.

Hinton, E. (2021). America on fire: The untold history of police violence and black rebellion since the 1960s. HarperCollins.

Hutchings, V. L., Walton, H., Jr., & Benjamin, A. (2010). The impact of explicit racial cues on gender differences in support for confederate symbols and partisanship. The Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1175–1188.

Israel-Trummel, M., & Streeter, S. (2022). Police abuse or just deserts? deservingness perceptions and state violence. Public Opinion Quarterly, 86(1), 499–522.

Jacobsmeier, M. L., & Lewis, D. C. (2013). Barking up the wrong tree: Why Bo didn’t fetch many votes for Barack Obama in 2012. Political Science & Politics, 46(1), 49–59.

Jardina, A., & Piston, S. (2016). Dehumanization of black people motivates white sup- port for punitive criminal justice policies. In Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association.

Jardina, A., & Piston, S. (2021). The effects of dehumanizing attitudes about black people on whites’ voting decisions. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1–23.

Jefferson, H., Neuner, F. G., & Pasek, J. (2020). Seeing blue in black and white: Race and perceptions of officer-involved shootings. Perspectives on Politics, 19(4), 1165–1183.

Kaminski, R. J., & Jefferis, E. S. (1998). The effect of a violent televised arrest on public perceptions of the police: A partial test of Easton’s theoretical framework. Policing an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 21(4), 683–706.

Lerman, A., & Weaver, V. (2014). Arresting Citizenship The Democratic Consequences of American Crime Control. University of Chicago Press.

Levin, J., Arluke, A., & Irvine, L. (2017). Are people more disturbed by dog or human suffering?: Influence of victim’s species and age. Society & Animals, 25(1), 1–16.

Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1122–1135.

Maltzman, F., Lebovic, J. H., Saunders, E. N., & Furth, E. (2012). Unleashing presidential power: The politics of pets in the white house. Political Science & Politics, 45(3), 395–400.

McGowen, E. B., & Wylie, K. N. (2020). Racialized differences in perceptions of and emotional responses to police killings of unarmed African Americans. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 8(2), 396–406.

Mendelberg, T. (1997). Executing hortons: Racial crime in the 1988 presidential campaign. Public Opinion Quarterly, 61(1), 134–157.

Moore, Steven. (n.d.). Gorillas in Our Midst? Exploring the Political Consequences of Implicit Dehumanization. (unpublished paper)

Mummolo, J. (2018). Modern police tactics, police-citizen interactions, and the prospects for reform. The Journal of Politics, 80(1), 1–15.

Mutz, D. C. (2010). The dog that didn’t bark: The role of canines in the 2008 campaign. Political Science & Politics, 43(4), 707–712.

Ostfeld, M. C., & Yadon, N. (2022). Skin Color, Power, and Politics in America. Russell Sage Foundation Press.

Peay, P. C., & Camarillo, T. (2021). No justice! black protests? no peace: The racial nature of threat evaluations of nonviolent# blacklivesmatter protests. Social Science Quarterly, 102(1), 198–208.

Peffley, M., & Hurwitz, J. (2007). Persuasion and resistance: Race and the death penalty in America. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 996–1012.

Peffley, M., Hurwitz, J., & Sniderman, P. M. (1997). Racial stereotypes and whites’ political views of blacks in the context of welfare and crime. American Journal of Political Science., 41(1), 30–60.

Phoenix, D. L. (2019). The Anger Gap How Race Shapes Emotion in Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Quillian, L., & Pager, D. (2001). Black neighbors, higher crime? the role of racial stereotypes in evaluations of neighborhood crime. American Journal of Sociology, 107(3), 717–767.

Soss, J., & Weaver, V. (2017). Police are our government: Politics, political science, and the policing of race–class subjugated communities. Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 565–591.

Streeter, S. (2019). Lethal force in black and white: assessing racial disparities in the circumstances of police killings. The Journal of Politics, 81(3), 000–000.

Walker, H. L. (2020). Mobilized by injustice: Criminal justice contact, political participation, and race. Oxford University Press.

Walker, H., Collingwood, L., & Bunyasi, T. L. (2020). White response to black death: A racialized theory of white attitudes towards gun control (pp. 1–24). Social Science Research on Race.

Weaver, V., Prowse, G., & Piston, S. (2020). Withdrawing and drawing in political discourse in policed communities. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, 5(3), 604–647.

Weitzer, R. (2002). Incidents of police misconduct and public opinion. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(5), 397–408.

White, A. (2019). Family matters? voting behavior in households with criminal justice contact. American Political Science Review, 113(2), 607–613.

Williamson, V., Trump, K.-S., & Einstein, K. L. (2018). Black lives matter: Evidence that police-caused deaths predict protest activity. Perspectives on Politics, 16(2), 400–415.

Yadon, N. (2022). They Say We’re Violent”: The multidimensionality of race in perceptions of police brutality and BLM. Perspectives on Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722001013

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andra Gillespie, Steven Moore, Periloux Peay, Shea Streeter, audiences at the American Political Science Association, Midwest Political Science Association, Southern Political Science Association Annual Meetings, and members of the University of Michigan Interdisciplinary Workshop on American Politics for their feedback on earlier iterations of the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Crabtree, K., Yadon, N. Remaining Neutral?: White Americans’ Reactions to Police Violence and Policing. Polit Behav 46, 355–375 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09831-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09831-0