Abstract

The affective, identity based, and often negative nature of partisan polarization in the United States has been a subject of much scholarly attention. Applying insights from recent work in social psychology, we employ three novel large-N, broadly representative online surveys, fielded over the course of 4 years, across two presidential administrations, to examine the extent to which this brand of polarization features a willingness to apply dehumanizing metaphors to out-partisans. We begin by looking at two different measures of dehumanization (one subtle and one more direct). This uncovers striking, consistent observational evidence that many partisans dehumanize members of the opposing party. We examine the relationship between dehumanization and other key partisan intensity measures, finding that it is most closely related to extreme affective polarization. We also show that dehumanization “predicts” partisan motivated reasoning and is correlated with respondent worldview. Finally, we present a survey experiment offering causal leverage to examine openness to dehumanization in the processing of new information about misdeeds by in- and out-partisans. Participants were exposed to identical information about a melee at a gathering, with the partisanship of those involved randomly assigned. We find pronounced willingness by both Democrats and Republicans to dehumanize members of the out-party. These findings shed considerable light on the nature and depth of modern partisan polarization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

And why man is a political animal in a greater measure than any bee or any gregarious animal is clear ... for it is the special property of man in distinction from the other animals that he alone has perception of good and bad and right and wrong and the other moral qualities, and it is partnership in these things that makes a household and a city-state.

– Aristotle, Politics.

Partisan conflict in the United States is increasingly characterized by scholars as identity based, affective, and often negative in nature. Partisanship is frequently described and measured as a social identity (Abramowitz and Saunders 2006; Green et al. 2004; Greene 1999, 2000, 2004; Huddy et al. 2015; Klar 2013, 2014; Mason 2018; Nicholson 2012; Theodoridis 2013, 2017). This identity has long been known to fundamentally shape behavior in and perception of the political world (Bartels 2002; Bolsen et al. 2014; Druckman and Bolsen 2011; Duran et al. 2017; Fernandez-Vazquez and Theodoridis 2019; Jerit and Barabas 2012). Partisans now appear to dislike, desire social distance from, and discriminate against members of the opposing party in apolitical contexts (Huber and Malhotra 2017; Iyengar et al. 2012; Iyengar and Westwood 2015; McConnell et al. 2018; Nicholson et al. 2016). This rise in “affective polarization” has coincided with increased social and ideological sorting (Bishop 2009; Hetherington and Rudolph 2015; Levendusky 2013, 2009; Mason 2016, 2018; Mason and Wronski 2018), elite polarization (Hetherington 2001; Hetherington and Rudolph 2015), greater access to partisan news (Arceneaux et al. 2012; Henderson and Theodoridis 2017; Lelkes et al. 2015), disproportionately negative affect (Abramowitz and Saunders 2005; Abramowitz and Webster 2016; Druckman et al. 2019; Klar et al. 2018), and misconceptions regarding the extremity and characteristics of opposing partisans (Ahler 2014; Ahler and Sood 2018). We explore whether, in what ways, and to what ends, partisans in this hyper-polarized environment are willing to engage in one of the most pernicious forms of psychological marginalization studied in the context of intergroup relations: dehumanization.

We explore the prevalence and nature of partisan dehumanization by bringing to bear new data from three broadly representative, large-N national online surveys. Two of these surveys were fielded by YouGov as part of the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) and the other was run through Survey Sampling International (SSI). Our two CCES surveys were in the field surrounding mid-term elections, one under the Obama Administration and the other during the Trump Administration. Our SSI survey was fielded in the summer of 2018, when the salience of politics was presumably lower than amidst the heat of a campaign (Michelitch and Utych 2018). Our studies span 4 years, employ four distinct measures of partisan dehumanization, an array of relevant covariates, and two survey experiments.

We begin by establishing observationally the extent to which Democrats and Republicans perceive and are willing to describe members of the opposing party as metaphorically less than fully human. We do this using both subtle and blatant measures of dehumanization, showing that openness to dehumanizing language is relatively widespread, though by no means universal, among both Democrats and Republicans.

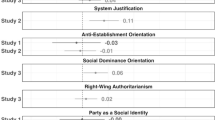

We go on to examine several correlates of dehumanization, comparing it to standard measures of affective polarization, partisan intensity, and authoritarianism/worldview. We find that affective polarization is most predictive of the tendency to dehumanize, and that the phenomenon is far more common among the most “affectively polarized” partisans. We show that dehumanization appears to be linked to a more authoritarian/fixed worldview, especially among Republican respondents. And, we use a survey experiment to measure the relationship between dehumanization and partisan bias, showing that the willingness to dehumanize out-partisans goes hand-in-hand with a willingness to engage in a common and important consequence of partisan identity—partisan motivated reasoning. In fact, dehumanization appears to be a more reliable marker for such biased perception than either traditional partisan strength measures or measures of differential affect.

Finally, we employ a novel survey experiment to gain the causal leverage necessary to investigate one particular context in which partisan dehumanization might be expected to asymmetrically emerge—upon the receipt of information regarding misbehavior by partisans. We see that partisans are substantially more willing to degrade transgressing out-partisans in dehumanizing terms.

A few recent studies in political science and social psychology have begun to measure and explore partisan dehumanization (Cassese 2019; Crawford et al. 2013; Pacilli et al. 2016). Most notably, Cassese’s (2019) groundbreaking research in the pages of this journal examines partisan dehumanization in the context of the 2016 presidential election. Where this prior work has tended to focus on social and psychological correlates of dehumanization, such as moral and social distance, our attention is more expressly political. We focus on the place of dehumanization in modern partisanship and polarization, looking at some of their most notable hallmarks (e.g. partisan intensity, affect, motivated reasoning, and worldview). As such, our examination represents a significant contribution to the extensive literature in political science on affective polarization by showing the pernicious form it now consistently takes in America’s contemporary political environment. Our experimental results also shed new light on the potential underlying causal mechanisms behind this phenomenon. And, our representative samples and over-time data allow us to make population inferences valid across political contexts.

Our findings speak to the broader psychological literature on dehumanization by (1) exploring the phenomenon using representative samples, and (2) examining a case in which there is no clear dominance by one group. Prior work on dehumanization has tended to focus on intergroup contexts with one dominant group and one subordinate group (e.g., Blacks and whites, immigrants and citizens, criminals and juries).Footnote 1

From Affect to Animals

That dehumanization in the partisan context has not been more extensively explored is perhaps surprising, given the prevalence of dehumanizing language in American politics. Political elites often use uncivil language, and have occasionally slipped into dehumanizing rhetoric about their opponents. During the 1932 election campaign, Franklin Roosevelt’s supporters called Herbert Hoover a “fat, timid capon.” More recently, such dehumanization has intensified and proliferated. Bill Maher called Republicans “treasonous rats,” and Alex Jones responded by calling Democrats “the ultimate cowardly sacks of garbage.” Harry Reid has called President Trump the GOP’s “Frankenstein monster,” and Eric Trump said Democrats investigating his father were “not even people.” As these examples show, political elites have long engaged in partisan dehumanization of each other. Rank-and-file partisans are known to take cues about group norms and appropriate behavior from political elites (Lenz 2012; McLaughlin et al. 2017), so such comments by leaders and the overall vitriol of the political moment might be expected to trickle down. Thus, our focus here is on whether, to what extent, and in what forms this behavior exists in the the mass public.

Modern conceptions of dehumanization began with Kelman (1973), who characterized it as the denial of humanity to victims in order to justify violence. If victims are not quite human, “the principles of morality no longer apply to them” ( Kelman 1973, p. 48). More recently, dehumanization has been studied in more ordinary, day-to-day contexts. Leyens et al. (2000) defined dehumanization in terms of denying that groups or individuals possess uniquely human traits. Using this expanded definition of dehumanization, scholars have measured its presence in diverse contexts including the depictions of presidential candidates (Cassese 2018), immigrants and refugees (Esses et al. 2013; Utych 2017), members of the LGBT community (Fasoli et al. 2016), and perpetrators of crimes (Bastian et al. 2013).

Dehumanization is thought to justify harsh and inhumane treatment of out-group members in extreme intergroup conflict (Bandura 1999; Bandura et al. 1975; Kelman 1973). Dehumanized groups are often victims of discrimination (Kteily et al. 2015), mistrust (Vezzali et al. 2012), and even violence (Kelman 1973). When people view a group as less than human they are increasingly willing to punish its members (Stevenson et al. 2015). Further, the effects of dehumanization may function at an automatic, unconscious, or implicit level. For instance, Mekawi et al. (2016) found that shooting bias by whites toward African-Americans was greater among individuals who dehumanized black people. Along these lines, extant work has shown that dehumanization is not merely affect. Dehumanization has been shown to activate distinct neural pathways from mere dislike or negative affect, suggesting that dehumanization is more than simply extreme dislike (Bruneau et al. 2018). Specifically, Bruneau et al. (2018) show that different brain structures are activated when respondents were asked to respond to a dehumanization measure versus when they responded to feeling thermometers of different out-groups. So, a willingness for in-partisans to dehumanize out-partisans may be different in kind from mere negative affect (although, as we show, the two are statistically associated).

In the broader sense, dehumanization may mark a significant step toward depriving individuals who belong to certain groups or categories of individual-level depth or complexity of feelings, motivation, or personality. In the partisan context, this brand of dehumanization would have partisans distinguishing themselves and their co-partisans as “more human” than supporters of the out-party. This might represent an extension of the general desire to boost self-esteem by elevating in-groups relative to out-groups (Tajfel and Turner 1986). It could also be consistent with the psychological tendency to attribute negative behavior by out-group members dispositionally while attributing similar behavior by in-group members situationally (while doing the reverse for good behavior) (Pettigrew 1979). By depriving political opponents, to even a small extent, of the complex thoughts and scruples we often associate with humanity, we make them easier to stereotype and we may more readily ascribe simpler, more base, and even nefarious, motivations to them. This is consistent with the general impulse to view in-groups as complex and textured, and out-groups as one-dimensional and monolithic (Simon and Mummendey 1990). The language of partisan dehumanization is consistent with such a simplified view of the world, even if partisans do not literally believe their opponents to be sub-human.

In the context of American politics, there may well be material implications of partisans not only disliking each other, but characterizing members of the out-party as less than fully human. Dehumanization, even metaphorical in nature, might be expected to lead to reluctance to compromise (Leidner et al. 2013) and more gridlock (Hetherington and Rudolph 2015; Hetherington and Weiler 2018). In the current context of hyper-polarized partisan conflict and with today’s segmented media environment, the effects of dehumanization could also show up as a willingness to believe anything (fake news and conspiracy theories) about the other side or to justify unethical behavior or political tactics by one’s own side. In some instances, dehumanization may even render partisan violence acceptable. James Hodgkinson provides a chilling cautionary anecdote. In June 2017, Hodgkinson approached Congressional Republicans and staff as they practiced for the annual Congressional Baseball Game for Charity and opened fire, injuring four people before being killed by Capitol Police. Just months before, Hodgkinson had posted a series of statements on Facebook, including one calling Donald Trump “inhuman.” More recently, Cesar Sayoc tweeted over and over again about “liberal slime” and “scum degenerates” before sending pipe bombs to more than a dozen critics of President Trump. While uncommon, these events underscore the need to understand the potential psychological seeds of partisan violence. Dehumanizing rhetoric has been conspicuously common among those willing to go from partisan animosity to violence.

Measuring Partisan Dehumanization and Its Correlates

Data and Methods

Our data come from three separate large-N, broadly representative online surveys conducted at very different moments in the electoral calendar across 4 years and two presidential administrations. The experimental study we discuss later in this article was fielded by YouGov as part of a 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) module (\(N=1199\)). Our descriptive analysis emerges from studies we ran on two separate online samples at different points in 2018. One of these was of Survey Sampling International (SSI) panelists (N = 1000) and was fielded in June of 2018. The other was fielded by YouGov in a module of the 2018 CCES (N = 1625).Footnote 2 We begin by examining the tendency to dehumanize using a series of measures from the SSI and 2018 CCES samples. Participants were asked to respond to two measures of dehumanization.

Our SSI respondents completed Leyens’ Infrahumanization scale (Leyens et al. 2000), which is meant to measure a subtle form of dehumanization where respondents attribute fewer secondary (that is, more uniquely human) emotions to the out-group than to the in-group. Specifically, participants were asked to rate (on a scale from 1 = not at all to 7 = very likely) the extent to which members of the Republican and Democratic parties are likely to feel different emotions, including admiration, love, shame, and resentment. Subtle dehumanization is said to occur if the average rating for the opposing party is lower than the average rating for one’s own party, and this difference constitutes our measure of subtle dehumanization. The eight items (four emotion ratings for each party) demonstrate considerable scale reliability (\(\alpha = .78\)).

Our SSI and 2018 CCES respondents were presented with a much more direct measure of dehumanization—Kteily et al.’s (2015) blatant dehumanization scale, accompanied with a graphic depicting the classic ‘ascent of man.’ Because some readers may be unfamiliar with this metric, we reproduce the graphic in Fig. 1. (The numeric scale is modeled on a classic feeling thermometer.) This measure is designed as an intuitive, direct assessment of dehumanization. There is little ambiguity (or subtlety) regarding what the respondent is being asked. This psychometric tool measures the degree to which humanity is denied (at one end of the spectrum) versus affirmed or ascribed (at the other end of the spectrum). This measure has been shown to predict consequential outcomes (attitudes and behavioral tendencies) beyond mere dislike (see Kteily and Bruneau 2017; Kteily et al. 2015). The difference between the out-group rating and the in-group rating constitutes our measure of blatant dehumanization.

Respondents for both our 2018 CCES and SSI surveys responded to the standard 7-point party identification question, and feeling thermometer ratings for both Democrats and Republicans. Our SSI subjects also responded to a partisan closeness measure and an experiment designed to measure partisan motivated reasoning.

Results

Our first goal is to determine whether partisans are willing to dehumanize members of the opposing party, and establish how widespread this willingness is. Figure 2 shows the distributions of our two measures of dehumanization. As a reminder, any score above zero on either measure is interpreted as indicating the presence of dehumanization. For both measures, the modal respondent is just above zero, reflecting a slight tendency to dehumanize. A substantial proportion of partisans are willing to directly say that they view members of the opposing party as less evolved than supporters of their own party. Among SSI respondents, the mean score on the blatant difference measure is just over 31 points out of a possible 100. That figure for our 2018 CCES sample was nearly 36. As a point of comparison, these gaps are more than twice the dehumanization differences found by Kteily et al. (2015) for Muslims (14 points) and nearly four times the gap for Mexican immigrants (7.9 points) when comparing these groups with evaluations of “average Americans.” In our SSI study, nearly 77% of respondents said out-party members were less evolved than in-party members, and about 65% offered at least a 10-point difference. We find similar results in our 2018 CCES study: the average partisan scored nearly 36 on the blatant dehumanization scale. Just over 80% of respondents scored above 0, and 69% scored above 10.

The average value for the subtle measure is about .7 out of 6, and 59% of respondents dehumanized members of the opposing party to some degree. For this measure, the density of respondents near zero is much greater, suggesting, perhaps counter-intuitively, that partisans are far more willing to dehumanize directly than to deprive their opponents of these particular human traits.

These results make clear that many partisans are clearly willing to dehumanize members of the out-party, and are not particularly shy about expressing it. Democrats and Republicans tend to dehumanize members of the outparty at similar rates. Furthermore, the consistency across time periods and samples, is remarkable. At the same time, for both subtle and blatant dehumanization, we observe substantial density at or just above zero, indicating that dehumanization is by no means a universal feature of partisanship. Because this group of individuals clustered around zero may be a normatively desirable model, we conducted an analysis to determine whether individuals who refuse to dehumanize members of the outparty are systematically different from those who do not. We find that those who refuse to dehumanize are less affectively polarized, feel less close to their party, and pay less attention to political news than those who do dehumanize. We discuss some of these covariates more fully in the coming sections.

Figure 2d shows that subtle and blatant dehumanization are closely, though not perfectly, related to each other, with respondents far more willing to use the full range of the blatant scale. This may reflect the measurement qualities of each assessment tool. While the blatant measure simply requires moving the outparty slider further down than the inparty slider, the subtle measure requires thinking about each emotion and to what extent members of each party feel that emotion. On the other hand, the blatant measure gives respondents a much more direct expressive opportunity to describe outparty members as less human than their own group members.

These figures show the distribution of our measures of partisan dehumanization from the 2018 CCES and SSI surveys. The fourth subfigure shows the relationship between the blatant and subtle measures on the SSI survey. In the fourth subfigure, points indicate individual responses, and the line shows the result of a local regression (LOESS curve)

Dehumanization and Partisan Intensity

Having demonstrated that many, but not all, partisans are willing to dehumanize out-partisans, we next look at the extent to which this willingness correlates with standard measures, and the underlying constructs they seek to measure, of partisan identity/intensity.

We begin with the standard 7-point party identification scale, which divides the respondents into pure Independents, leaners, not-so-strong partisans, and strong partisans. Because pure Independents have no in-party or out-party, they do not have a dehumanization score, and cannot be included in any of our analyses. Figure 3 plots the partisan strength measure against our blatant and subtle measures of dehumanization. As we might expect, strong partisans tend to dehumanize out-party members more than not-so-strong partisans and leaners. But, the most notable feature of the relationship is that there isn’t much of one. As other work has suggested before (Theodoridis 2017), the traditional partisan strength measure does not appear to be capturing the features of partisanship behind this manifestation of the attachment.

These figures show the relationship between our dehumanization measures (on the y axis) and a measure of party strength (x axis) constructed by folding the seven-point party identification scale. The points indicate individual responses, jittered to increase readability. The line shows the result of a local regression (LOESS curve)

Our SSI survey also included a measure of partisan “closeness” similar to one commonly used in a comparative multi-party context (for example, see Brader and Tucker 2008; Huber et al. 2005; Ishiyama and Fox 2006). This scale is meant to approximate identity-based measures of partisan identification (Bankert et al. 2017; Huddy et al. 2015; Miller et al. 1981). Respondents who identified as partisans were asked how close they felt to their party: not very close, somewhat close, or very close. Because social identification is associated with ingroup glorification and outgroup denigration (Tajfel and Turner 1979), we might expect that dehumanization is more highly correlated with these identity-based measures of partisanship.

Figure 4 plots the partisan closeness measure against our blatant and subtle measures of dehumanization. Those who felt very close to their party dehumanized out-party members much more than those who felt only somewhat close or not very close to their party. Indeed, this closeness measure appears to relate more strongly to dehumanization than the standard seven-point scale. Still, the relationship is underwhelming.

These figures show the relationship between blatant and subtle partisan dehumanization (y axis) and a measure of party closeness (x axis). The party closeness question stem reads, “How close do you feel to the [respondent’s party] do you feel?” The points indicate individual responses, jittered to increase readability. The line shows the result of a local regression (LOESS curve)

Dehumanization and Affective Polarization

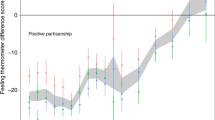

The difference between in- and out-party feeling thermometers has emerged as a standard individual-level measure of affective polarization (Iyengar et al. 2012; Iyengar and Westwood 2015), which has emerged as the dominant conceptual characterization of modern partisan polarization. Figure 5 plots each respondent’s level of affective polarization and dehumanization, along with a spline. To begin with, we see that affective polarization is substantially more predictive of dehumanization (especially of the blatant variety) than either of the partisan intensity measures discussed above.Footnote 3 Comparison of these measures also provides some sense of whether, as Bruneau et al. (2018) would suggest, dehumanization is conceptually distinct from affective polarization. If dehumanization and affective polarization were conceptually equivalent, we would expect a roughly linear relationship—as affective polarization increases, we would expect a similar increase in dehumanization. Notably, the tendency to dehumanize appears to increase sharply at the very top of the affective polarization scale. In all, while the neural correlates of these two phenomena may differ, affect and dehumanization do appear to be very strongly related to each other in the case of partisanship.

However, the raw levels for each measure do suggest that respondents use the blatant dehumanization and partisan feeling thermometer scales differently, even though both ranged from 0 to 100. While a large number of subjects were willing to respond with large feeling thermometer differences, they were much less willing to use the full dehumanization scale. In our SSI study, the mean feeling thermometer difference is roughly 46 points, while the mean blatant dehumanization score is roughly 31 points. In our 2018 CCES study, the mean feeling thermometer difference is about 51, while the blatant dehumanization score is about 36. Only the most extremely affectively polarized individuals appear comfortable using the full range of the blatant dehumanization scale.

These results suggest that the extremely affectively polarized may be qualitatively different from those who are less polarized. We analyzed the group of respondents who scored at least 70 on the affective polarization scale compared to those who scored less. The extremely affectively polarized tend to be stronger partisans and feel closer to their party. They are also older and more likely to be male. Overall, while the two correlated phenomena are conceptually and empirically distinct (Kteily and Bruneau 2017; Martinez 2014; Waytz and Epley 2012), affect and dehumanization appear to go hand-in-hand in the domain of political partisanship.

These figures show the relationship between our measures of partisan dehumanization and affective polarization. Affective polarization is measured by subtracting outparty feeling thermometer rating from inparty feeling thermometer rating. Points indicate individual responses, and the line shows the result of a local regression (LOESS curve)

Dehumanization and Worldview

Scholars have increasingly associated a set of questions about preferred traits in children with partisanship and the expanding affective polarization in America (Hetherington and Weiler 2009, 2018; Stenner 2005). These studies rely on the standard four-item child rearing battery, which asks respondents to choose “desirable” traits for a child from four pairs (Respect for elders vs. Independence, Good manners vs. Curiosity, Obedience vs. Self-Reliance, and Well behaved vs. Considerate). This has most commonly been used as a proxy for authoritarianism. In hopes of avoiding the pejorative connotation of that term, we adopt the language of Hetherington and Weiler (2018), who have applied the scale as a measure of worldview, a construct they describe as ranging from fluid to fixed. Those with fluid worldviews tend to seek new experiences and see change as exciting. Those with a fixed worldview are less open to change, and more attuned to danger and perceived threats. Increasingly, those with fixed and fluid worldviews have sorted into the Republican and Democratic parties, respectively, deepening the partisan divide. Thus, we examine the relationship between this attitude and the tendency to dehumanize. Regardless of the label, a clear relationship emerges. Prior work has found a relationship between blatant dehumanization and authoritarianism (Kteily et al. 2015) as well as it’s conceptual cousin Social Dominance Orientation (Trounson et al. 2015). We find a similar relationship. And, not surprisingly, the relationship is strongest among Republicans. Figure 6 plots each respondent’s worldview by our two dehumanization measures.

In the SSI study, regressing blatant dehumanization on the fluid-to-fixed scale reveals that those at the lowest end of the scale tend to differentially dehumanize outparty members by about 11 points less than those at the top of the scale, even when controlling for party. Among Republicans, the effect is even stronger—Republicans with the most fixed worldview dehumanized Democrats over 21 points more than those with the most fluid worldview (see Table II in the Online Appendix). We find similar results in the 2018 CCES data, as those with fixed worldview differentially dehumanize outparty members by nearly 12 points. Again, the effect is much stronger for Republicans, where an individual with a very fixed worldview will on average dehumanize outparty members by nearly 28 points more than one with a very fluid worldview (see Table III in the Online Appendix).

These figures show the relationship between our two measures of partisan dehumanization and “worldview”, often referred to as authoritarianism. The worldview scale is constructed using the four standard child-rearing items, and higher values on this scale indicate a more fixed, authoritarian worldview. Points indicate individual responses, jittered to increase readability. The line shows the result of a local regression (LOESS curve)

Dehumanization and Partisan Motivated Reasoning

Partisan bias or partisan motivated reasoning is among the most studied and noteworthy consequences of partisanship (Bartels 2002; Campbell et al. 1960). To examine how this tendency is related to dehumanization, we use an experimental manipulation involving a “news” report about a Senator engaged in lying about the issue positions of his opponent (see Theodoridis 2017). Respondents were assigned to read a report about either a Senator from their own party or a Senator from the opposing party. The reports were identical except for the party of the Senator. After reading the report, respondents were asked whether they agree or disagree with several statements: (1) This report seems fair. (2) The person who wrote this is probably biased (reverse coded). (3) This sort of thing is important to me when deciding which candidate to support. (4) The Senator deserves credit for admitting this (reverse coded). (5) The behavior that got the Senator in trouble is typical. The scale items were designed to capture some common mechanisms for motivated reasoning—bias, discounting, assignment of exculpatory credit, and attribution error (as measured by the typicality of the behavior). We generated a simple additive scale with these five items and calculate motivated processing by subtracting, between subjects, the value when respondents read an article about a co-partisan from the value when respondents read an article about an opposing partisan.

Figure 7a plots the average level of bias among those who scored in each tercile of the blatant dehumanization scale. Terciles are used because they allow for comparison with the standard measure of partisan strength. We see a non-linear relationship between blatant dehumanization and perceptual bias. Levels of bias among those who dehumanize within the first and second tercile are virtually identical, while those in the upper tercile display much more partisan motivated reasoning. Figure 7b illustrates the relationship between partisan bias and subtle dehumanization. The relationship here is even more pronounced. While it appears more linear, we once again see only those who dehumanize the most statistically standing out from the rest of respondents. These results contrast with the relationships between bias and affective polarization or standard partisan strength. Terciles of these measures do not appear to meaningfully “predict” levels of partisan motivated reasoning (see Figs. VII and VIII in the Online Appendix).

These figures show the relationship between our two measures of partisan dehumanization and partisan bias, or motivated reasoning. The x-axis displays terciles of our measures of partisan dehumanization. The y-axis displays a scale of motivated processing described in the text, along with bootstrapped confidence intervals

Our studies and descriptive analyses above have yielded several notable results. First, we uncover consistent (across time and sample) evidence that partisans are willing to dehumanize members of the opposing party in both subtle and blatant ways. Second, we show that this tendency to dehumanize is not unique to members of one political party - both Democrats and Republicans tend to dehumanize each other at roughly similar rates. Third, we find that dehumanization is closely related with affective polarization, but that only the most affectively polarized are willing to use the full range of the dehumanization scales. Fourth, we demonstrate that strong partisans, those who feel close to their party, and those with more fixed worldviews are more likely to dehumanize political opponents. Finally, we observe that partisan dehumanization is linked with partisan motivated reasoning.

Causal Leverage: Dehumanization in Information Processing

Method

We ended the previous section by demonstrating that those who are willing to dehumanize outparty members are also more likely to engage in motivated information processing. We now attempt to expand on that analysis using a separate study that exposes a potential mechanism through which observed dehumanization may develop, offers another set of measures demonstrating the pervasiveness of the phenomenon, and provides an additional context in which it emerges. Motivated processing is one potential mechanism for how partisan dehumanization has arisen in the public. As the media environment has become more fractured and partisan sources of political news have become available, partisans are increasingly exposed to depictions of outparty members misbehaving. Fox News viewers are regularly exposed to stories about campus protests that turn violent. MSNBC viewers saw extended coverage of rowdy rallies where candidate Trump sometimes encouraged violence against protesters. But, it is possible that perceptions of the other side as less human could emerge even without media segmentation and selective exposure. Those who view events through partisan lenses may be more likely to dehumanize outpartisans upon viewing misdeeds.

In order to examine this information processing mechanism, which could produce the overall partisan dehumanization we have measured, we fielded a survey experiment as part of the 2014 CCES designed to provide the necessary causal leverage.Footnote 4 Because we are interested in whether partisans engage in dehumanization of the opposing party, pure independent voters were again excluded from analysis a priori.

Participants were exposed to a fictitious news story that displayed an image and contained a short description of a political event. The image showed an outdoor area in which several broken plastic chairs were strewn in a disorderly fashion. The chairs in the image were red, white, and blue to suggest a patriotic theme. Only physical objects were displayed; no humans were shown. During exposure to this image, participants were randomly assigned to view one of two vignettes. Both vignettes were made to resemble online newspaper articles describing a fight that broke out at either a Democratic or Republican party gathering. The only difference between the vignettes was the party hosting the gathering. Figure 8 shows a the full language of the Republican vignette.Footnote 5,Footnote 6

After participants read the vignette, they were asked to rate the people in the news story on several 5-point rating scales designed to measure two types of dehumanization—animalistic and mechanistic (Haslam 2006; Haslam and Loughnan 2014). Animalistic dehumanization concerns the distinction between humans and animals. Those who are dehumanized in this way are often seen a less refined, less civilized, and lacking in self-control. Mechanistic dehumanization concerns the distinction between humans and automatons. Those who are dehumanized in this way are seen as cold and lacking emotion. Two conceptually-derived items operationalized each form of dehumanization. For animalistic dehumanization, items were “They are uncivilized” and “They are like animals.” For mechanistic dehumanization, items were “They are like robots” and “They have no feelings.” The items of each set were highly correlated, r = .67 and r = .49, respectively. Although participants made ratings with a scale anchored at 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree (with a labeled midpoint of 3 = neither agree nor disagree), we re-coded the scale so that 0 became the midpoint. Thus, numerically the scale became − 2 (strongly disagree), − 1 (disagree), 0 (neither agree nor disagree), 1 (agree) and 2 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a greater degree of dehumanization.

Results

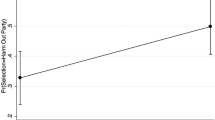

Dehumanization measures were subjected to a 2 (political party affiliation: Republican vs. Democrat) × 2 (perpetrator of misdeed: Republican-perpetrated vs. Democrat-perpetrated) between-participants Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). We first analyzed the animalistic dehumanization outcome variable.

We find that Republicans are marginally more likely to dehumanize the perpetrators than Democrats overall. This partisan difference is statistically significant (\(\beta\) = .31, SE = .08). Among Republicans, participants dehumanized the people in the Democrat-perpetrated misdeed (M = .33, sd = 1.04) relative to the people in the Republican-perpetrated misdeed (M = .03, sd = 1.15). Among Democrats, participants dehumanized the people in the Republican-perpetrated misdeed (M = .18, sd = 1.02) relative to the people in the Democrat-perpetrated misdeed (M = − .09, sd = 1.05).

We conducted a parallel analysis for the mechanistic dehumanization outcome variable. Again, we find that Republicans are marginally more likely to dehumanize the perpetrators than Democrats overall (\(\beta\) = .20, SE = .08). Among Republicans, participants dehumanized the people in the Democrat-perpetrated misdeed (M = − .26, sd = .93) relative to the people in the Republican-perpetrated misdeed (M = − .51, sd = 1.04). Among Democrats, participants dehumanized the people in the Republican-perpetrated misdeed (M = − .40, sd = .98) relative to the people in the Democrat-perpetrated misdeed (M = − .62, sd = .97).

Interestingly, the average level of mechanistic dehumanization is below the midpoint of the scale, whereas the average level of animalistic dehumanization is above the midpoint. In other words, respondents were more comfortable calling the perpetrators “animals” than “robots.” This, perhaps, makes sense given the context of the treatment. According to the vignettes provided to respondents, the perpetrators had gotten into a fight and went so far as to throw and break chairs as a result. This behavior is clearly more animal-like than robotic—that is, emotionally hot, rather than cold and devoid of feeling. We expect that were the treatment to describe an event displaying, for example, a lack of empathy, we might observe higher levels of mechanistic dehumanization and lower levels of animalistic dehumanization.

The results of this experiment are consistent with partisan cognition patterns that, over time, might produce the overall dehumanization found in our observational results. When presented with information about misdeeds, partisans typically perceive out-party members as animal-like, but are prone to forgive the transgressions of fellow party members (Fig. 9).

These figures show the results of our dehumanization experiment for both animalistic and mechanistic dehumanization. The x-axis displays the respondent’s party identification, and the y-axis displays either animalistic or mechanistic dehumanization. The points indicate the average level of dehumanization given the partisanship of the perceived offender and of the respondent. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals

Discussion: Party Animals?

Using three large-N, broadly representative surveys spanning 4 years and including four different measures and two experimental manipulations, we find that partisans are consistently willing to dehumanize members of the opposing party. First, we find strong observational evidence of dehumanization. We see that dehumanization appears to be very much related to affective polarization, especially of the extreme variety. Though conceptually and empirically distinct, out-party dehumanization may have origins in affective polarization, and it could subsequently exacerbate partisan divides. Second, we find that partisan dehumanization is strongly predicted by worldview/authoritarianism. Third, our results suggest that the tendency to dehumanize out-partisans goes hand-in-hand with partisan motivated reasoning. Fourth, we see that partisans receiving information about misdeeds by the other side far more readily dehumanize the other party–and this happens on both sides of the aisle. These results suggest a new form of partisan polarization. Partisans are willing to explicitly state that members of the opposing party are like animals, that they lack essential human traits, and that they are less evolved than members of their own party. These findings may help us better understand the nature and toxicity of contemporary partisan conflict.

That both Democrats and Republicans engage in this behavior at roughly the same rate is perhaps surprising given that prior work has shown significant correlations between factors that predict both conservatism and propensity to dehumanize out-groups, such as authoritarianism (Kteily et al. 2015), disgust sensitivity (Stevenson et al. 2015), and social dominance orientation (Trounson et al. 2015). These results of reciprocal partisan dehumanization constitute a novel contribution that might guide future empirical inquiry.

While the current paper identifies partisan dehumanization in the mass public, subsequent work should do more to identify the causes and consequences of partisan dehumanization. One immediately identifiable cause is extreme partisan rhetoric. As described above, political elites occasionally use language that likens partisan groups to animals or objects. Future work should investigate how these dehumanizing utterances influence overt behavior. While implications of dehumanization have been explored (Maoz and McCauley 2008; Martinez et al. 2011; Tam et al. 2007; Vaes et al. 2002) in other contexts, they may manifest differently in a political setting. For example, Leidner et al. (2013) find people prefer aggressive rather than diplomatic solutions to conflict with a dehumanized group. In politics, this may translate into an unwillingness to compromise on political issues, a trend that many scholars have observed (and which many lament) as deleterious to the democratic enterprise.

Most concerning is the possibility that dehumanization might lead to increased partisan violence. We briefly mentioned two recent events—the man who attempted to shoot Republican senators as they practiced softball and the man who sent pipe bombs to at least 13 critics of President Trump. Clearly, most partisans will not engage in this type of violence, irrespective of their responses to an online survey. However, as norms of civility deteriorate and some groups increasingly see members of the outparty as dangerous rather than simply misguided, we may see more violent clashes between partisans.

Notes

While electoral politics in the United States establishes political winners and losers, neither party has recently held a consistent, unassailable grip on all branches and levels of government. Both parties are well-funded and while one party may lose political power temporarily, each tends to ascend to power on a regular basis. Political parties exist not in a static hierarchy but a dynamic system where political power shifts back and forth between them.

YouGov uses block randomization to maximize representativeness. For the SSI sample, we imposed population based quotas for joint distributions of race and education to maximize broad representativeness. This sample is reasonably representative of the national population, although it contains comparatively more women and fewer middle-aged people than the national population. The distributions of demographic variables can be found in the Appendix.

We also plot the relationship between blatant dehumanization and each individual party feeling thermometer. It does not appear that the result is driven by inparty or outparty affect alone - both feeling thermometers have similar relationships with blatant dehumanization. See Fig. VI in the Online Appendix.

In keeping with the suggestions of Miratrix et al. (2018) the analyses presented here do not use sampling weights. Distributions of sample demographics including age, race, gender, household income, and partisanship can be found in the Appendix.

We also included an ambiguous condition that did not specify whether the perpetrator group was composed of Republicans or Democrats. For interpretational clarity, we exclude this condition from the focal analysis. Based on recent work, we suspect that although political party was not explicitly mentioned in this ambiguous condition, many participants might infer that their rival political party committed the misdeed.

It is possible that some respondents may make assumptions/inferences regarding the race of the partisans involved, specifically that Democrats are more likely non-white. In fact, Ahler and Sood (2018) show that voters overestimate the percentage of Democrats who are black. Having said that, we made a conscious choice in the design of this experiment to not guide respondents to imagine white Democrats or Republicans, either through the text or image. This is because we view racial associations as part of the admittedly bundled party label treatments.

References

Abramowitz, A., & Saunders, K. (2005). Why can’t we all just get along? The reality of a polarized America. The Forum, 3(2), 1.

Abramowitz, A., & Saunders, K. (2006). Exploring the bases of partisanship in the American electorate: Social identity vs. ideology. Political Research Quarterly, 59(2), 175.

Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. (2016). The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of us elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies, 41, 12–22.

Ahler, D. J. (2014). Self-fulfilling misperceptions of public polarization. The Journal of Politics, 76(3), 607–620.

Ahler, D. J., & Sood, G. (2018). The parties in our heads: Misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. The Journal of Politics, 80(3), 964–981.

Arceneaux, K., Johnson, M., & Murphy, C. (2012). Polarized political communication, oppositional media hostility, and selective exposure. Journal of Politics, 74(1), 174–186.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209.

Bandura, A., Underwood, B., & Fromson, M. E. (1975). Disinhibition of aggression through diffusion of responsibility and dehumanization of victims. Journal of Research in Personality, 9(4), 253–269.

Bankert, A., Huddy, L., & Rosema, M. (2017). Measuring partisanship as a social identity in multi-party systems. Political Behavior, 39(1), 103–132.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Bastian, B., Denson, T. F., & Haslam, N. (2013). The roles of dehumanization and moral outrage in retributive justice. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e61842.

Bishop, B. (2009). The big sort: Why the clustering of like-minded America is tearing us apart. Boston: Mariner Books.

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., & Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36(2), 235–262.

Brader, T., & Tucker, J. A. (2008). Pathways to partisanship: Evidence from Russia. Post-Soviet Affairs, 24(3), 263–300.

Bruneau, E., Jacoby, N., Kteily, N., & Saxe, R. (2018). Denying humanity: The distinct neural correlates of blatant dehumanization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(7), 1078–1093.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Cassese, E. C. (2018). Monster metaphors in media coverage of the 2016 U.S. presidential contest. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6(4), 825–837.

Cassese, E. C. (2019). Partisan dehumanization in American politics. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09545-w.

Crawford, J. T., Modria, S. A., & Motyl, M. (2013). Bleeding-heart liberals and hard-hearted conservatives: Subtle political dehumanization through differential attributions of human nature and human uniqueness traits. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 86–104.

Druckman, J., Gubitz, S., Levendusky, M., & Lloyd, A. (2019). How incivility on partisan media (de-)polarizes the electorate. The Journal of Politics, 81(1), 291–295.

Druckman, J. N., & Bolsen, T. (2011). Framing, motivated reasoning, and opinions about emergent technologies. Journal of Communication, 61(4), 659–688.

Duran, N. D., Nicholson, S. P., & Dale, R. (2017). The hidden appeal and aversion to political conspiracies as revealed in the response dynamics of partisans. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 73, 268–278.

Esses, V. M., Medianu, S., & Lawson, A. S. (2013). Uncertainty, threat, and the role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of immigrants and refugees. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 518–536.

Fasoli, F., Paladino, M. P., Carnaghi, A., Jetten, J., Bastian, B., & Bain, P. G. (2016). Not “just words”: Exposure to homophobic epithets leads to dehumanizing and physical distancing from gay men. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(2), 237–248.

Fernandez-Vazquez, P., & Theodoridis, A. G. (2019). Believe it or not? Partisanship, preferences, and the credibility of campaign promises. Journal of Experimental Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2019.16

Green, D., Palmquist, P. B., & Schickler, P. E. (2004). Partisan hearts and minds. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20(2), 393–403.

Greene, S. (2000). The psychological sources of partisan-leaning independence. American Politics Quarterly, 28(4), 511–537.

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153.

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264.

Haslam, N., & Loughnan, S. (2014). Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 399–423.

Henderson, J. A., & Theodoridis, A. G. (2017). Seeing spots: Partisanship, negativity and the conditional receipt of campaign advertisements. Political Behavior, 40(4), 965–987.

Hetherington, M. J. (2001). Resurgent mass partisanship: The role of elite polarization. American Political Science Review, 95(3), 619–631.

Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington won’t work: Polarization, political trust, and the governing crisis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. D. (2018). Prius or pickup? How the answers to four simple questions explain America’s great divide. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Huber, G. A., & Malhotra, N. (2017). Political homophily in social relationships: Evidence from online dating behavior. The Journal of Politics, 79(1), 269–283.

Huber, J. D., Kernell, G., & Leoni, E. L. (2005). Institutional context, cognitive resources and party attachments across democracies. Political Analysis, 13(4), 365–386.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Ishiyama, J., & Fox, K. (2006). What affects the strength of partisan identity in Sub-Saharan Africa? Politics & Policy, 34(4), 748–773.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Jerit, J., & Barabas, J. (2012). Partisan perceptual bias and the information environment. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 672–684.

Kelman, H. G. (1973). Violence without moral restraint: Reflections on the dehumanization of victims and victimizers. Journal of Social Issues, 29(4), 25–61.

Klar, S. (2013). The influence of competing identity primes on political preferences. The Journal of Politics, 75(4), 1108–1124.

Klar, S. (2014). Partisanship in a social setting. American Journal of Political Science, 58(3), 687–704.

Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., & Ryan, J. B. (2018). Affective polarization or partisan disdain? Untangling a dislike for the opposing party from a dislike of partisanship. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(2), 379–390.

Kteily, N., & Bruneau, E. (2017). Backlash: The politics and real-world consequences of minority group dehumanization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(1), 87–104.

Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., & Cotterill, S. (2015). The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 901–931.

Leidner, B., Castano, E., & Ginges, J. (2013). Dehumanization, retributive and restorative justice, and aggressive versus diplomatic intergroup conflict resolution strategies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(2), 181–192.

Lelkes, Y., Sood, G., & Iyengar, S. (2015). The hostile audience: The effect of access to broadband internet on partisan affect. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 5–20.

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became Democrats and conservatives became Republicans. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. (2013). How partisan media polarize America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Leyens, J.-P., Paladino, P. M., Rodriguez-Torres, R., Vaes, J., Demoulin, S., Rodriguez-Perez, A., et al. (2000). The emotional side of prejudice: The attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 186–197.

Maoz, I., & McCauley, C. (2008). Threat, dehumanization, and support for retaliatory aggressive policies in asymmetric conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(1), 93–116.

Martinez, A. G. (2014). When “they” become “I”: Ascribing humanity to mental illness influences treatment-seeking for mental/behavioral health conditions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(2), 187–206.

Martinez, A. G., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2011). The power of a label: Mental illness diagnoses, ascribed humanity, and social rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(1), 1–23.

Mason, L. (2016). A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(1), 351–377.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mason, L., & Wronski, J. (2018). One tribe to bind them all: How our social group attachments strengthen partisanship. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 257–277.

McConnell, C., Malhotra, N., Margalit, Y., & Levendusky, M. (2018). The economic consequences of partisanship in a polarized era. American Journal of Political Science, 62(1), 5–18.

McLaughlin, B., McLeod, D. M., Davis, C., Perryman, M., & Mun, K. (2017). Elite cues, news coverage, and partisan support for compromise. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(3), 862–882.

Mekawi, Y., Bresin, K., & Hunter, C. D. (2016). White fear, dehumanization, and low empathy: Lethal combinations for shooting biases. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 322–332.

Michelitch, K., & Utych, S. (2018). Electoral cycle fluctuations in partisanship: Global evidence from eighty-six countries. The Journal of Politics, 80(2), 412–427.

Miller, A. H., Gurin, P., Gurin, G., & Malanchuk, O. (1981). Group consciousness and political participation. American Journal of Political Science, 25(3), 494–511.

Miratrix, L. W., Sekhon, J. S., Theodoridis, A. G., & Campos, L. F. (2018). Worth weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments. Political Analysis, 26(3), 275–291.

Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 52–66.

Nicholson, S. P., Coe, C. M., Emory, J., & Song, A. V. (2016). The politics of beauty: The effects of partisan bias on physical attractiveness. Political Behavior, 38(4), 883–898.

Pacilli, M. G., Roccato, M., Pagliaro, S., & Russo, S. (2016). From political opponents to enemies? The role of perceived moral distance in the animalistic dehumanization of the political outgroup. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(3), 360–373.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1979). The ultimate attribution error: Extending Allport’s cognitive analysis of prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 5(4), 461–476.

Simon, B., & Mummendey, A. (1990). Perceptions of relative group size and group homogeneity: We are the majority and they are all the same. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20(4), 351–356.

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stevenson, M. C., Malik, S. E., Totton, R. R., & Reeves, R. D. (2015). Disgust sensitivity predicts punitive treatment of juvenile sex offenders: The role of empathy, dehumanization, and fear. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 15(1), 177–197.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior: Psychology of intergroup relations, red. S. Worchel, LW Austin. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 5, 7–24.

Tam, T., Hewstone, M., Cairns, E., Tausch, N., Maio, G., & Kenworthy, J. (2007). The impact of intergroup emotions on forgiveness in Northern Ireland. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10(1), 119–136.

Theodoridis, A. G. (2013). Implicit political identity. PS: Political Science & Politics, 46(03), 545–549.

Theodoridis, A. G. (2017). Me, myself, and (I), (D), or (R)? Partisanship and political cognition through the lens of implicit identity. The Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1253–1267.

Trounson, J. S., Critchley, C., & Pfeifer, J. E. (2015). Australian attitudes toward asylum seekers: Roles of dehumanization and social dominance theory. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(10), 1641–1655.

Utych, S. M. (2017). How dehumanization influences attitudes toward immigrants. Political Research Quarterly, 71(2), 440–452.

Vaes, J., Paladino, M.-P., & Leyens, J.-P. (2002). The lost e-mail: Prosocial reactions induced by uniquely human emotions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41(4), 521–534.

Vezzali, L., Capozza, D., Stathi, S., & Giovannini, D. (2012). Increasing outgroup trust, reducing infrahumanization, and enhancing future contact intentions via imagined intergroup contact. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 437–440.

Waytz, A., & Epley, N. (2012). Social connection enables dehumanization. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 70–76.

Acknowledgements

We thank Doug Ahler, Steve Ansolabehere, Vin Arceneaux, Larry Bartels, Henry Brady, Erin Cassese, Jack Citrin, Maggie Deichert, Stephen Goggin, John Henderson, Nathan Kalmoe, Cindy Kam, David Karol, Lily Mason, Steve Nicholson, David Nickerson, Eric Schickler, Gaurav Sood, and Rob Van Houweling for helpful feedback. This research was made possible by generous funding from the University of California, Merced, and the Vanderbilt University Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, and was supported by National Science Foundation Awards #1559125 and #1756447. We also thank the Vanderbilt Research on Individuals, Politics and Society Lab. Replication and online supplementary materials are available here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FY7SVG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martherus, J.L., Martinez, A.G., Piff, P.K. et al. Party Animals? Extreme Partisan Polarization and Dehumanization. Polit Behav 43, 517–540 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09559-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09559-4