Abstract

Supreme Court confirmation hearings have been famously called a “vapid and hollow charade” by Elena Kagan. Indeed, perceptions of nominees’ refusal to answer questions about pending cases, prominent political issues, or give any hint of their ideological leanings have become a cornerstone of the modern confirmation process. We investigate the extent to which this reticence to speak of their ideological views, or candor, influences how individuals evaluate the nominee. To this end, we present the results of a survey experiment which examines how support for a hypothetical Supreme Court nominee is affected by information, especially when a nominee is presented to be very forthright or very reticent in answering ideological questions during the confirmation hearings. We find that while partisan compatibility with the president is the main determinant of support for a nominee, nominees who refuse to answer ideological questions can bolster support from respondents who would not support them on partisan grounds. We supplement these findings with observational state-level support data from real nominees over the last 40 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The televised Senate confirmation hearings are often the only exposure the mass public gets to U.S. Supreme Court nominees before they are given lifetime seats on the nation’s highest Court. As such, understanding how those confirmation hearings influence how the public learns about and evaluates a nominee enhances our knowledge of how public opinion on the Court and its justices is formed. That said, nominees in the modern era are notoriously reticent when asked about their ideological beliefs or jurisprudential approaches. During her confirmation hearings, Justice Ginsburg stated flatly, “I cannot say one word on that subject that would not violate what I said had to be my rule about no hints, no forecasts, no previews” (see Gaziano and Meese 2005). Since Ginsburg, other nominees have followed her lead in refusing to answer ideological questions about how they might rule (Farganis and Wedeking 2011; Comiskey 1994).

This has led some scholars, including now-Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan to question whether confirmation hearings have any value in teaching the Senate, or the public, about the nominee. Indeed, prior to her nomination to the Supreme Court, Kagan famously called the confirmation hearings “vapid and hollow charades” which have become little more than “official lovefests.” She concluded that “[a] process so empty may seem ever so tidy-muted, polite, and restrained-but all that good order comes at great cost” (Kagan 1995, p. 941).

If Kagan is right, and nominees’ lack of candor makes the hearings little more than a “dog and pony show” which have little informational value, why have them? One suggestion, popularized by Gibson and Caldeira (see Gibson and Caldeira 2009a, b) argues that because attention to the Court heightens exponentially during the confirmation process, senators and nominees can use the hearings to engender symbolic loyalty toward the Court as an institution.Footnote 1 Under this view, nominees’ refusal to clearly articulate their views should help the Court as an institution but the question remains: what effect does invoking the “Ginsburg Rule” have on support for the nominees themselves? This is the central question our project seeks to answer.

In short, we posit that confirmation hearings have the unique ability to shape citizens’ evaluations of the nominees themselves. To that end, we examine the effect of nominee candor on evaluations of nominee. We argue that, given the broad media environment, nominees can position themselves to bolster support for their confirmation by being reticent and even evasive at confirmation hearings, especially among those who are ideologically predisposed to oppose the nominee. We further argue that nominees who are forthcoming about their views (e.g., Robert Bork) do little to advance their support among those predisposed to agree with them but that nominees who are reticent about expressing their views (e.g., Ruth Bader Ginsburg) can increase support from members of the public on the other side of the aisle by saying as little as possible. By way of previewing our results, we find that while partisan compatibility with the president is the main determinant of support for a nominee, nominees who refuse to answer ideological questions can bolster support from respondents who would not support them on partisan grounds. We supplement these findings with observational state-level support data from real nominees over the last 40 years.

These results offer a number of important contributions to the literature. First and foremost, we argue that understanding how citizens evaluate nominees is critical to our understanding of the process more fully. While much is understood about how presidents select their nominees, and how senators choose to vote to confirm or reject them, much less is understood about how the mass public makes evaluations of nominees. The fact that the confirmation hearings and the nominee seem to receive greater attention with each nominee indicates that public perception and evaluation of the president’s choice is important. Indeed, nomination and confirmation of justices is the closest locus of control the American people have over the federal judiciary, especially the Supreme Court, which sits atop the nation’s only unelected branch of government. Recent work by Kastellec (2010) suggests that senators and, to a lesser extent, presidents respond to public support for a nominee (see also Overby et al. 1992). Further, if candor or reticence has implications for citizens’ evaluations of a nominee, as our results suggest, a richer and more normatively pleasing story can be told about the confirmation hearings. Indeed, prospective justices may be better serving the Court and the nation by following the Ginsburg Rule.

Our exploration begins with a discussion of the theory and expectations surrounding how citizens form judgements about nominees, drawing widely from the literature on candidate evaluations and Supreme Court confirmations, as well as psychological theories of learning and message elaboration. We then turn to our research design and results. Finally, we conclude with a larger discussion of the implications of our results and directions for future research.

Candor and Judging Nominees

In many ways, the public’s evaluation of Supreme Court nominees can be thought of as merely an example of a political attitude. Thus, we begin with the assumption that evaluations of nominees to the Supreme Court should be formed similarly to other political evaluations. Attitude formation, of course, is a social psychological function; our ultimate attitude a result of inter-personal cues as well as messages received from the broader environment (Petty and Cacioppo 1996). This research, however, concerns a narrower conception of attitudes: the formation of political attitudes. Following Zaller’s (1991; 1992) tradition, we conceive of political attitudes as a function of receptivity to certain messages, acceptance (or refusal) of that message, and the internal cognitive sampling of these various inputs when reporting an attitude. The more pertinent question is not necessarily how political opinions are formed, but rather what information informs these decisions.

The most important political considerations focus on party identification and ideology. In essence, partisan and ideological congruence between an individual and a political figure or political action consistently ranks as the most important political factor (Bartels 2002; Campbell et al. 1960; Converse 1964; Lewis-Beck et al. 2008). While partisanship has historically proven more predictive of political attitudes than ideological views, recent work suggests the two may be more intertwined than previously believed (Chen and Goren 2016).

We are confident, therefore, in our belief that partisanship and ideology will shape evaluations of political figures, including nominees to the Supreme Court. Decades of research demonstrates the power of political predispositions to not only shape candidate evaluations (Campbell et al. 1960; Lewis-Beck et al. 2008), but also alter interpretations of political news and objective facts (Bartels 2002; Dancey and Sheagley 2013; Goren 2005). Predispositions, therefore, serve as important heuristics (i.e., cognitive shortcuts), providing voters with summary information to evaluate politicians without the necessity of learning every issue position or biographical detail.

Political attitudes, while important, are almost certainly not the only factors considered by the public when evaluating nominees. Scholars have long been interested in the question of what factors lead a nominee to be selected by the president and confirmed by the Senate. These considerations offer an instructive starting place when identifying the factors that might influence the general public. Nemacheck (2008) identifies several patterns which lead to nominee emergence, notably shared ideological values (a quality we already see reflected in the general public) as well as qualifications that can be presented convincingly to the American public. Tellingly, when announcing a nominee, presidents rely heavily on the nominee’s qualifications with the intent to appeal and sway public opinion and pressure the Senate (Johnson and Roberts 2004), as well as alter the salient considerations that voters rely on when evaluating the nominee (Zaller 1992). Research overwhelmingly supports the notion that ideology and qualifications are the two dominant factors that influence a senator’s support for a nominee as well as that nominee’s chances of being confirmed (Caldeira and Wright 1998; Cameron et al. 1990; Epstein et al. 2006; Ruckman 1993; Segal 1987).Footnote 2

That said, it is less clear if ideology and partisanship are the factors the public wants senators to use when evaluating a nominee. In a 2009 survey, Gibson (2010) finds that only 10% of respondents believe that it is “very important” that a justice base her decisions on whether she is a Republican or Democrat and only 13% believed it was very important she base those same decisions on being liberal or conservative. By contrast, 65% believed it was very important justices appear to be fair and impartial and a resounding 74% placed upholding the framers’ views as very important. We know partisanship and ideological agreement strongly influence political attitudes. The Supreme Court is unique, however, in that the public seems to place a premium on a Court that, at least in appearance, eschews both partisanship and ideology. So what role can the confirmation hearings play in resolving this tension?

As confirmation hearings take an increasingly high profile role, we propose that media coverage of these events provide citizens with a unique opportunity to learn about the nominee. In essence, these hearings provide information about the ideology of the nominee, her qualifications, and even occasionally a glimpse into her personality. Yet tradition, as noted earlier, demands that nominees withhold a fair amount of information during confirmation hearings (Farganis and Wedeking 2011, 2014), thus reducing the amount of information someone can gain from the coverage. Indeed, some scholars even suggest that this reticence to answer questions can influence a nominee’s chances of being confirmed (Wedeking and Farganis 2010).

Before we continue, we note that the decision to provide or withhold information usually concerns information about the nominee’s ideological positions; that is, their beliefs about specific political issues. While it is possible for nominees to be reticent about personal information, the most common form of reticence is ideological reticence. Thus, while we do not discount the possibility of other types of reticence, we focus on ideological reticence.

Kelly (2010) adds that while citizens evaluate nominees on two criteria (ideological agreement and “judiciousness”, or their qualifications and competence), under conditions when little ideological information is available, judiciousness is sufficient to judge the nominee. Nominees with limited records or who are less than candid may, in fact, benefit with the citizenry, provided their qualifications are acceptably high. In short, reticence may not hurt a nominee. An NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll taken during the confirmation process of Chief Justice Robert underscores this point. It revealed that 57% of respondents believe nominees should not be required to state their positions on salient political issues during the hearings; only 36% believed they should (NBC News/Wall Street Journal 2005).

We propose that this tradition of reticence is not only historically necessary, but strategically important for maintaining public support for the nominee. As more ideological information becomes available to voters, attitudes are far more likely to polarize along ideological lines than to converge (Lord et al. 1979; Munro and Ditto 1997). A nominee who withholds information not only preserves institutional tradition, but also avoids disclosing ideological information that could polarize supporters and opponents.

Reticence as a virtue and hearings as a source of ideological information are important questions to assess, but they miss another important signal that reticence sends to voters: information about the nominee’s trustworthiness and character. The trustworthiness of the nominee is vital to understanding the persuasive power of their message. Psychological theories of persuasion tell us that message effectiveness is conditional not only on the strength of the argument, but also on perceptions of the source (Bagozzi et al. 2002; Petty and Cacioppo 1986). Trustworthy sources are generally seen as more persuasive, and thus usually lead to greater elaboration (or consideration) of the arguments being presented. Trustworthiness can be enhanced in a number of ways, including by working contrary to your self-interest (Combs and Keller 2010).

In addition, partisan congruence influences perceptions of trustworthiness and credibility. Character weaknesses (sometimes operationalized as scandals) not only change feelings of political trust (Hetherington and Rudolph 2008), but are also closely tied to partisan bias and motivated reasoning (Goren 2002, 2007). The ability to overlook seemingly damning information about your fellow partisans is deeply rooted in the psychology of motivated reasoning (Kunda 1990) and shows up even outside of the American context (Anduiza et al. 2013).

Conventional wisdom, as well as recent examples like Ginsburg, tells citizens that it is in the best interest of a Supreme Court nominee to say little and get out of the confirmation battle unscathed. Thus, the more forthcoming a nominee is, the more likely this is to be seen as against her own interests, leading to an increase in elaboration and consideration of the argument. Additionally, message elaboration is enhanced when the source makes deeper consideration easy, by repeating the message (Cacioppo and Petty 1989) or, in our case, providing more information about their political position. Message elaboration, however, is not always a net positive. Greater elaboration of messages from political opponents can lead to more counter arguments, entrenchment, and polarization rather than persuasion (Kunda 1990; Lodge and Taber 2013; Taber and Lodge 2006).

Importantly, as noted above, these cognitive processes rely on ideological candor, rather than personal candor (or candor about other aspects of their life and qualifications). Thus, while voters may appreciate nominees who are forthcoming about their personal struggles, for example, this information is less likely to be seen as working against their interests, as it does not pertain to the conventional wisdom of the nomination process. Indeed, nominees that are forthcoming about personal struggles may actually benefit from this candor (in contrast to our hypotheses about ideological candor), as a focus on personal issues can lead to greater elaboration of the message around their personal lives and, potentially, lead to sympathy or empathy for the nominee’s story. We believe, however, that personal candor (as opposed to ideological candor) is less important to the nomination process, as modern presidents and nominees all attempt to construct a positive personal narrative through anecdotes and a focus on a nominee’s “story”, resulting in minimal variance on personal candor.Footnote 3 The same cannot be said for ideological candor.

Some of the earliest research examining how the public forms judgments about judicial nominees flows nicely from these general precepts. For example, Gimpel and Ringel (1995) conclude that when nominees face controversy (and thus are paid more attention), those opposed to and in support of a nominee focus on different aspects of the nominee. Those opposed to confirmation tend to use arguments about ideology while those in favor focus on the nominees’ character, qualifications, or the role of the president. On either side, however, Gimpel and Ringel conclude that evaluations come predominantly from media and elite discourse. Citizens learn about the nominee from elites and use that information to form judgments (see also Guliuzza et al. 1992).

Partisanship and ideology, therefore, influence evaluations of Supreme Court nominees both directly and indirectly through the consideration of arguments and information about the nominee. Unsurprisingly and to preview our results, the strongest direct predictor of nominee support is partisan or ideological congruence with the nominating president. Our concern with this research is the conditioning effect of partisan congruence. Our predictions follow work on motivating information processing (Kunda 1990) and the use of counter-attitudinal information (Taber et al. 2009), as we believe respondents will spend cognitive effort and time to argue against information and nominees that are incongruent with their beliefs. This enhanced cognitive effort actually creates an increased effect for forthcoming nominees as greater amounts of ideological information are available to citizens, but this effect is not beneficial to their confirmation.

In practice, forthcoming nominees, by nature of working against their own interest, are seen as more trustworthy, leading to greater elaboration of the message. For individuals who agree with the nominee and president, this process should work to enhance evaluations of nominees, such that for voters who share the partisan or ideological bent of the nominee, the more forthcoming a nominee is, the greater the level of support for the nominee (H1).

On the other hand, ideological incongruence should lead to division, not convergence. Thus, we believe that for voters who do not share the partisan or ideological position of the nominee, the more forthcoming a nominee is, the lower the level of support for that nominee (H2). In sum, the more a nominee divulges ideological information that differentiates them from a generic nominee, the greater the polarization between supporters and opponents.

Experimental Research Design

We test these two hypotheses using two pieces of evidence: a survey experiment conducted on http://Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk online workplace and observational data from recent Supreme Court nominations.Footnote 4 Beginning with the experimental evidence, we recruited 727 respondents to participate in a study about public figures fielded from 25 March to 30 March 2015. After taking a brief survey about their political beliefs and demographics, subjects were asked to evaluate a fictional Supreme Court nominee.Footnote 5

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of several conditions. The first manipulation varied the gender of the nominee. No differences between these conditions were found and the male and female treatment groups were collapsed in our analyses. The second manipulation varied the ideology of the nominee through the media environment and the partisanship of the fictional nominating president. Starting with responses to questions about party identification and ideology, respondents were classified as receiving either a pro- or counter-attitudinal nominee. Thus, when a nominee was presented as a Democratic nominee, respondents who reported a Democratic identification on the branched party identification scale were categorized as pro-attitudinal and those with a Republican identification were categorized as counter-attitudinal. Independents were then categorized by whether they identified as liberal or conservative, with liberals coded as pro-attitudinal for Democratic nominees and conservatives as counter-attitudinal. Moderate independents were not included in the analyses.Footnote 6 The reverse of these codes were used when the nominating president was portrayed as a Republican. Finally, subjects were assigned to one of two treatment conditions.

The treatment conditions varied the reticence of the nominee. Both treatment groups saw a transcript and short news article about a portion of the confirmation hearing. One group received a transcript where the nominee was restrained in his or her comments (reticent) while the other group received a transcript with a nominee who discussed the ideological issues at length (forthcoming). This difference represents the key experimental manipulation of nominee reticence.

Subjects were randomly assigned to either the reticent, or forthcoming conditions using the randomization feature in the Qualtrics Research Suite. All respondents read a short biography of the nominee (found in the Appendix). After reading the biography, respondents were given a link to access the DPTE, which is a program developed by Lau and Redlawsk (2006) to simulate the media environment more realistically than a standard static information board.

Subjects were given time to practice working with the DPTE software, seeing non-political stories, and then proceeded to the experimental portion of the study. After practicing, subjects saw a scrolling list of headlines about the Supreme Court nominee. Participants were given 5 min to learn about the nominee, which they did by clicking on headlines that interested them and reading information about the nominee. Every three seconds a new piece of information appeared at the bottom of the screen and the oldest piece of information scrolled off the top of the screen. Additionally, when a subject selected an article, the information covered the entire screen. Headlines continued to scroll in the background. Thus, reading an article exerted opportunity costs on the subject in the form of missed chances to view other information.

In addition to the available headlines, our manipulation forced respondents to see the confirmation hearing transcript. For subjects in the reticent treatment, the transcript reflected a nominee who closely followed the Ginsburg Rule, refusing to comment on issues that might come before the Court. In the forthcoming treatment, the nominee openly discussed his or her beliefs. The timer for the environment was stopped and participants were unable to proceed until they had closed the confirmation hearing transcript. The text of the confirmation hearing transcript for both treatment conditions can be found in the Appendix.

After completing the DPTE portion of the experiment, participants were given a link re-directing them back to the Qualtrics Research Suite. Once they followed this link, they were asked a number of questions about the nominee. Participants rated the respondent on a 101-point feeling thermometer, were asked about their level of support for the nominee and certainty of that opinion, and whether they believed the nominee was qualified to serve as a Supreme Court Justice. Responses between Qualtrics and the DPTE were linked with a randomly assigned, unique numerical subject ID created in the DPTE. We use this ID to match responses in Qualtrics to behavioral data in the DPTE while preserving subject anonymity. After completing this portion of the study, subjects were thanked for their participation and given a confirmation code to enter into Mechanical Turk in order to be paid.Footnote 7

Before we continue, we pause briefly to discuss our sample. While Mechanical Turk is not a nationally representative sample, the convenience sample is useful for experiments in political science. Rather than rely on student samples or geographically constrained convenience samples, Mechanical Turk workers represent a cross-section of Americans. Admittedly, the sample demographics are not representative, but random condition assignment removes the need for a representative sample, provided our conclusions are constrained to the sample population. We discuss some potential limitations of our sample and steps we took to account for these limitations in the Appendix.

Experimental Results

As noted above, our hypotheses address generalized support of a Supreme Court nominee under conditions of forthcomingness or reticence. Although a single item measuring support could be used, we instead construct an aggregated index of three measures of support.Footnote 8 First, we use a 101-point affective feeling thermometer rating of the nominee, which asks respondents to rate how warm or cold they feel towards the nominee. We also use a seven-point question that asks respondents whether they support or oppose the nominee’s confirmation and we use a five-point question about how qualified the respondent believes the nominee is to serve on the Supreme Court. We scale all of these variables to run from 0 to 1, with 0 representing the lowest level of support and 1 representing the highest level of support. We then average these three variables, creating an index with each item receiving equal weight. Therefore, our measure of support ranges from 0 to 1, like the originally scaled variables. The resulting scale shows strong reliability and cohesiveness, with an \(\alpha\) reliability coefficient of 0.85 and a principal-factor analysis eigenvalue on the first factor of 2.05, with one retained factor.

Following construction of this scale, we employ ordinary least squares regression, such that coefficients provide percentage point changes in the dependent variable. Therefore, a hypothetical coefficient of 0.15 on the experimental dummy variable represents a 15-point increase in the support dependent variable when moving between experimental conditions.

What, then, is the effect of a nominee’s reticence in a confirmation hearing on support for the nominee? We begin by examining the differences between the treatment groups (forthcoming vs. reticent) to see if what the nominee says alters public opinion. Table 1 presents the results of this analysis. As Table 1 shows, this is no main effect for nominee reticence, which demonstrates that the mechanism is not as simple as support increases as nominees withhold information.

Indeed, these results show a lack of support for H1, as the base condition is a pro-attitudinal nominee. Thus, forthcoming nominees are seen as no more or less positively by those who agree with them than reticent nominees. This effect may be due to a ceiling effect; wherein pro-attitudinal nominees can essentially do no wrong. Put differently, when a nominee accords with your beliefs, their relative unwillingness to disclose information in a confirmation hearing has little influence on your support of that nominee.

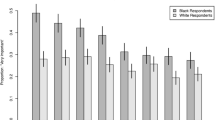

Figure 1 plots the mean level of support for forthcoming and reticent nominees among pro- and counter-attitudinal respondents. Although the theoretical maximum is 1, this figure show remarkably high levels of observed support among pro-attitudinal respondents. If anything, forthcoming nominees are viewed slightly more positively by pro-attitudinal respondents (as predicted by H1), although these differences are not statistically significant in our analysis.

While we are hesitant to draw too many inferences from this null finding, the results are interesting when put in the context of the body of literature that suggests the Court is, in general, more supported when it appears less ideological and justices act more as “umpires in robes” than subjective adjudicators (see e.g., Gibson and Caldeira 1992, 2009a, b; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2001). Our results suggest that if your partisanship matches the nominee, you are neither bothered nor excited about the appearance of a nominee being either judicious or ideological. This accords with more recent work suggesting that ideology and support for the Court and its decisions are much more intertwined than previously believed (Bartels and Johnston 2013; Christiansen and Glick 2015; Badas 2016). In short, for members of the president’s party, there is little the confirmation hearings can do to help or hurt support for the nominee. Confirmation hearings are a show put on for the opposition.

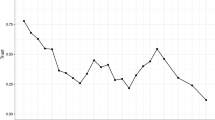

Unsurprisingly, there is a strong main effect for counter-attitudinal nominees, such that nominees that are incongruent with a respondent’s political beliefs enjoy markedly lower support (shown clearly in the right side of Fig. 1). However, our primary interest is in the conditioning effect of partisan congruence on candor and support. Turning attention to our interactive test of H2, we find clear support. Reticent nominees are seen more positively than forthcoming nominees among counter-attitudinal respondents, as indicated by the significant interaction term between condition assignment and attitude congruence. Figure 2 plots the marginal effect of the reticent condition under the pro- and counter-attitudinal conditions. Although the marginal effect of condition assignment is not significant in either condition, the difference between the effects is significant.

These findings underscore the implications of nominee candor for public opinion surrounding the nomination battle. In the experimental context, nominees who were particularly forthcoming fared significantly worse among out-party voters than reticent nominees. In our hypothetical nomination battles, the Ginsburg strategy consistently bests the Bork strategy, at least among those individuals politically disinclined to support the nominee.

These results accord well with work showing the important role of ideology in judicial evaluations (Bartels and Johnston 2013; Christiansen and Glick 2015; Badas 2016). As nominees disclose more information about their ideological positions, negative views of the nominee increase for those who disagree, while positive views fail to increase (likely due to a ceiling effect). Despite what citizens may say they desire in a nominee, ideological candor is not rewarded, as is in fact punished by some.

Observational Evidence

These results, while supportive of our second hypothesis, are by definition somewhat artificial. Respondents were asked to read and evaluate the nominees as they would a real nominee, but they were fictional nominees and fictional presidents, and the sample was unrepresentative of the general population, reducing external validity. We supplement these results, therefore, with observational data from prior Supreme Court nominations.

Data and Methods

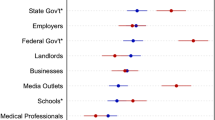

To test our hypotheses with evidence from historical nomination battles, we constructed a dataset coupling a measure of how forthcoming a nominee was with state-level partisanship data and state-level estimates of support for the nominee. Specifically, we began with Farganis and Wedeking’s (2014) dataset which codes every exchange (question by a senator and response by a nominee) by its level of candor from fully/very forthcoming to qualified (a reason for not answering was given, along with a partial answer), to not forthcoming where the nominee chose not to answer the question at all (see also Wedeking and Farganis 2010; Farganis and Wedeking 2011). From these exchanges Wedeking and Farganis were able to generate the percentage of nominee responses that were either qualified responses or not forthcoming. We sum these percentages to obtain a “reticence” percentage and then divide this by the percentage of forthcoming responses summed with the percentage of reticence answers. This provides us a relative measure of a nominee’s forthcomingness in their Senate confirmation hearings.Footnote 9

We then merged these data with state-level predictions of support for each nominee generated by Kastellec (2010). Using multilevel regression and poststratification, Kastellec (2010) disaggregated all national surveys on a nominee by first modeling the survey response as a function of demographic and geographic independent variables and then weighting those estimates by the percentage of actual values of each of those predictors in each state.Footnote 10 This procedure thus creates a state-by-state estimate of the average level of support for the nominee. This becomes our dependent variable in the analysis below.

Finally, we merged these data with state-level estimates of partisanship. Using Kastellec et al. (2010) data, which measures state-level partisanship by year, we constructed measures of partisan congruence with the nominating president. When a Republican president was in office, our measure of partisan congruence equals the percentage of Republican identifiers in the state for the year of the nomination. When a Democratic president was in office, the measure equals the percentage of Democratic identifiers in the state for the year of the nomination. Higher values of partisan congruence indicate a higher percentage of the population identifies with the president’s party, while lower values indicate a lower percentage of the population identifies with the president’s party. Using these data, we are able to analyze 10 recent nomination battles.Footnote 11

In short, we modeled state-level support for a nominee as a function of the nominee’s candor during his or her hearings interacted with the state’s partisan congruence with the president. These data provide a real-world test of our hypotheses by allowing us to examine natural variation in nominee reticence and its effect on state-level support. Of course, the best observational test of this hypothesis would be to look at a pooled cross-sectional measure of individual-level responses to questions about support for a nominee and compare that to the nominee’s forthcomingness. However, survey wording and method varies from nominee to nominee and often surveys do not include questions about respondents’ partisanship or the amount of attention they paid to the hearings. These data limitations forced us to look for a proxy of support. We believe a state-by-state analysis is preferable to a national-level analysis because it creates greater variability on the dependent variable. Rather than one very rough national-level measure of support for a nominee and national-level measure of partisanship, we have 50 data points for each nominee with varying levels of support and partisanship. We believe a state-by-state analysis, while not perfect, can be used as an additional test of our experimental results. Specifically we can form a proxy by examining the effect of reticence in states with higher or lower levels of partisan support for the nominating president. While not directly comparable to our experimental results (at least without committing the ecological fallacy), we believe these results supplement our results nicely.

The relevant comparison (between nominee reticence and state partisan make-up), however, cannot be easily modeled as the data occur at two different levels of analysis. To account for this, we utilize a multi-level modeling framework, which allows for cross-level interactions. Furthermore, while our dependent variable (state-level support) occurs at one level of analysis (the state) and our independent variables occur at both the state-level and the nominee-level, our data are not naturally hierarchical. That is, it is not obvious whether states should be nested in nominees or nominees nested in states. To avoid these issues, we employ a cross-classified model with cross-level interaction terms.Footnote 12

Observational Results

The results in Table 2 show results consistent with for H2 and offer convergent results to our experimental evidence. Again, party congruence increases support for a nominee, as expected, but we again observe a significant interaction between nominee reticence and state-level partisan congruence. Figure 3 plots the effects of nominee reticence and state-level partisan congruence (conditional on partisan congruence or reticence, respectively) on nominee support.

The left panel shows that in states with high levels of partisan congruence, there is little effect of nominee reticence or forthcomingness. In essence, nominees enjoy high support in high congruence states. On the other hand, in low partisan congruence states, reticence exerts a strong effect. Forthcoming nominees enjoy significantly less support in these states than reticent nominees. The right side of the figure plots the effects in reverse. Here we see the same expected pattern. Reticent nominees enjoy a relatively constant level of support, regardless of state-level partisan congruence. In contrast, forthcoming nominees in low congruence states enjoy lower levels of support compared to these nominees in high congruence states.

Furthermore, we can test for whether the difference in these marginal effects is statistically significant. For the left side of the graph, the marginal effects of reticence at low levels of congruence is 1.42 (p < 0.02) while the marginal effect at high levels of congruence is 0.40 (p < 0.52). The difference between these marginal effects is 1.02 [−1.59, −0.45]. As the confidence interval does not overlap zero, we conclude that the difference in the marginal effect of reticence at high and low levels of partisan congruence are significantly different.

Likewise, the marginal effect of partisan congruence for reticent nominees is 0.06 (p < 0.50), while the effect is 0.72 (p < 0.01) for forthcoming nominees. As before, we test for the significance of the difference between these two estimates. This difference of −0.66 [−1.02, −0.29] is once again statistically different. Thus, we conclude that partisan congruence exerts a stronger effect for forthcoming nominees than it does for reticent nominees. In totality, these results accord well with our experimental findings, suggesting that nominees that follow the Ginsburg strategy are likely to be more successful than those who follow in Bork’s footsteps.

Once again, “trustworthy” judges who openly discuss policy positions, while theoretically refreshing, are punished by citizens. Ideology and issue positions are vitally important in the nominee evaluation process and, as people learn about these positions, their attitudes actually polarize, driven largely by those who disagree with the nominee. More ideological information produces more opportunities for motivated processing and message elaboration, which in turn drives down support among political opponents.

Discussion

Taken together, our findings suggest a valuable strategic role for reticence in confirmation hearings. Supreme Court nominees who withhold information from senators (and by extension, the public), reduce the amount of information available to citizens to analyze and critique the nominee. While forthcoming nominees may be seen as working against their own interests, this can be a double-edged sword, as it leads to greater message elaboration and decreased support for the nominee among opposing partisans than a similar but reticent nominee would receive.

We tested this theory using an experiment, which demonstrated that reticent nominees enjoyed higher support among opposite party supporters than forthcoming nominees, and we supplemented this with a cross-classified analysis of 10 Supreme Court nominations, demonstrating that forthcoming nominees enjoyed lower levels of support in states with low partisan congruence than reticence nominees.

Reticence, therefore, is strategically important for Supreme Court nominees who wish to obtain broad public support. Even in light of polls that show American’s may prefer nominees to be forthright during the confirmation hearings, what the people say they want and what is in the best interest of the nominee are at odds. Forthcoming nominees polarize the electorate by providing additional ideological information to their detractors, which in turn produces diminished support for the nominee.

In addition to the potential to polarize opinions about the nominee, forthcoming nominees place the legitimacy of the institution at risk. Once considered a Teflon institution, recent work suggest there is a link between ideological agreement with the Court and perceptions of the Court’s legitimacy (see Bartels and Johnston 2013; Christiansen and Glick 2015). Although agreement with a decision and support for a nominee are not synonymous, the potential exists for citizens to translate their opposition to the nominee into broader system-level opposition. Future research should examine the link between nominee support or opposition and perceptions of institutional legitimacy. Nonetheless, by increasing the salience of ideological differences, forthcoming nominees potentially risk the Supreme Court’s vital levels of legitimacy.

It is this ideological candor that underscores the importance of judicial ideology in public opinion formation. Ideology matters not only through the direct mechanisms of support or opposition to candidates, but also indirectly by structuring reactions to the actions of a nominee. When faced with an ideological ally, citizens are highly supportive regardless of their actions. However, when confronting ideological foes, opinions are initially shaped by that opposition and, when the nominee willingly provides more ideological information, that opposition only intensifies. Due to this complex dynamic, nominees would be well advised to follow Ginsburg’s reticent confirmation path if they wish to engender broader public support.

Reticence, while potentially decried as undemocratic and against the spirit of the advice and consent process, is an effective and important public relations strategy for Supreme Court nominees. Among citizens who share the nominating president’s political leanings, reticence has little effect, positive or negative. Among those who are opposed to the president, however, reticence increases support while unrestrained nominees are met with greater scrutiny and, ultimately, lower evaluations. For a nominee who wishes to win over the general public, reticence rules.

Notes

See also Collins and Ringhand (2013), who argue that the confirmation hearings can act as a democratic forum of sorts and that the constitutional issues discussed during these hearings—whether nominees answer questions or not—provide a barometer of the social change the public is ready to accept.

It is worth noting that this dynamic may be a relatively recent one. Farganis and Wedeking (2014) demonstrates that partisanship, in particular, has only been a prominent feature in senators’ votes on nominees since the early 1980s.

While nominees can reveal a wide variety of types of information, we are concerned with ideological candor, both because it is the subject of debate among court observers (i.e., the Ginsburg Rule) and because we believe it is distinct from other types of candor because it references aspects of job performance and future rulings.

Replication data for the experimental and observational results we present below can be found on the Political Behavior Dataverse page doi:10.7910/DVN/NPQ3FB.

The Appendix presents the text of our manipulations and survey instrument. Mechanical Turk workers who opted in to the study were given a link to the survey. All questions outside of the dynamic process tracing environment (DPTE) were programmed using Qualtrics Research Suite.

Our final sample included 631 respondents. Twenty eight of our original respondents claimed to be complete independents/moderates and were thus excluded. The rest of the attrition in our analysis results from missing answers on the dependent variable, between 25 and 50 per question.

Subjects were paid one dollar for their participation. The survey took approximately 10 min to complete.

For interested readers, we present the analyses replicated with the individual items from the index in the Appendix.

This ratio ranges from a low of 8.3% for Judge Bork, meaning that of all his responses categorized as forthcoming, not forthcoming, and qualified, only 8.3% of these were qualified or not forthcoming, to a high of 31.6% for Justice Ginsburg, who was notoriously reticent in her confirmation hearings.

See Kastellec 2010, pp. 771–773 for full estimation details.

The data cover the confirmations of Justices Alito, Breyer, Ginsburg, O’Connor, Rehnquist (Chief Justice), Roberts, Sotomayor, Souter, and Thomas, as well as the failed confirmation of Judge Bork.

Our models also contain state-level controls for state partisanship, ideology, and a revised version of the Stimson (1999) mood measure created by Enns and Koch (2015) which disaggregates mood by state. These variables are included to account for the possibility that Democrats or symbolic or operational liberals are more or less likely to support nominees than Republicans or symbolic or operational conservatives. Only the state-level partisanship control obtains marginal significance, suggesting that partisan or ideological direction exerts little influence over nominee support.

References

Anduiza, E., Gallego, A., & Muñoz, J. (2013). Turning a blind eye experimental evidence of partisan bias in attitudes toward corruption. Comparative Political Studies, 46(12), 1664–1692.

Badas, A. (2016). The public’s motivated response to Supreme Court decision-making. Justice System Journal, 37(4), 318–330.

Bagozzi, R., Gurhan-Canli, Z., & Priester, J. (2002). The social psychology of consumer behavior. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Baker, R., Blumberg, S. J., Brick, M., Couper, M. P., Courtright, M., Michael Dennis, J., et al. (2010). Research synthesis: AAPOR report on online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(4), 711–781.

Bartels, L. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Bartels, B. L., & Johnston, C. D. (2013). On the ideological foundations of Supreme Court legitimacy in the American public. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 184–199.

Berinsky, A., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1989). Effects of message repetition on argument processing, recall, and persuasion. Basic and Applied Psychology, 10(1), 3–12.

Caldeira, G. A., & Wright, J. R. (1998). Lobbying for justice: Organized interests, Supreme Court nominations, and the United States Senate. American Journal of Political Science, 42(2), 499–523.

Cameron, C. M., Cover, A. D., & Segal, J. A. (1990). Senate voting on Supreme Court nominees: A neoinstitutional model. American Political Science Review, 84(2), 525–534.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Chen, P. G., Appleby, J., Borgida, E., Callaghan, T., Ekstrom, P., Farhart, C., et al. (2014). The Minnesota Multi-Investigator 2012 Presidential Election Panel study. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 14(1), 78–104.

Chen, P. G., & Goren, P. N. (2016). Operational ideology and party identification: A dynamic model of individual-level change in partisan and ideological predispositions. Political Research Quarterly, 69(4), 703–715.

Christiansen, D., & Glick, D. M. (2015). Chief Justice Roberts’ health care decision disrobed: The microfoundations of the Supreme Court’s legitimacy. American Journal of Political Science, 59(2), 403–418.

Collins, P. M, Jr., & Ringhand, L. A. (2013). Supreme Court confirmation hearings and constitutional change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Combs, D. J. Y., & Keller, P. S. (2010). Politicians and trustworthiness: Acting contrary to self-interest enhances trustworthiness. Basic and Applied Psychology, 32(4), 328–339.

Comiskey, M. (1994). The usefulness of Senate confirmation hearings for judicial nominees: The case of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. PS: Political Science and Politics, 27(2), 224–227.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in the mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent (pp. 206–261). New York: Free Press.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2014). Not in my backyard! Authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and support for strict immigration policies at home and abroad. Political Psychology, 35(3), 417–429.

Crawford, J. T., Brady, J. L., Pilanski, J. M., & Erny, H. (2013). Differential effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on political candidate support: The moderating role of message framing. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 5–28.

Crawford, J. T., & Pilanski, J. M. (2014). The differential effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on political intolerance. Political Psychology, 35(4), 557–576.

Dancey, L., & Sheagley, G. (2013). Heuristics behaving badly: Party cues and voter knowledge. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 312–325.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1991). Stability and change in the U.S. public’s knowledge of politics. Public Opinion Quarterly, 55(4), 583–612.

Enns, P. K., & Koch, J. (2015). State policy mood: The importance of over-time dynamics. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 15(4), 436–446.

Epstein, L., Lindsädt, R., Segal, J. A., & Westerland, C. (2006). The changing dynamics of Senate voting on Supreme Court nominees. Journal of Politics, 68(2), 296–307.

Farganis, D., & Wedeking, J. P. (2011). “No Hints, No Forecasts, No Previews”: An empirical analysis of Supreme Court nominee candor from Harlan to Kagan. Law and Society Review, 45(3), 525–559.

Farganis, D., & Wedeking, J. P. (2014). Supreme Court confirmation hearings in the U.S. Senate: Reconsidering the charade. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Gaziano, T. F., & Meese III, E. (2005). The Ginsburg rule. http://www.heritage.org/research/commentary/2005/07/the-ginsburg-rule.

Gibson, J. L. (2010). Expecting justice and hoping for empathy. Law and Courts Newsletter, 20(3), 21–25.

Gibson, J. L., & Caldeira, G. A. (1992). The etiology of public support for the Supreme Court. American Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 635–664.

Gibson, J. L., & Caldeira, G. A. (2009a). Citizens, courts, and confirmations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gibson, J. L., & Caldeira, G. A. (2009b). Confirmation politics and the legitimacy of the U.S. Supreme Court: Institutional loyalty, positivity bias, and the Alito nomination. American Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 139–155.

Gimpel, J. G., & Ringel, L. S. (1995). Understanding Court nominee evaluation and approval: Mass opinion in the Bork and Thomas cases. Political Behavior, 17(2), 135–153.

Goren, P. N. (2002). Character weakness, partisan bias, and presidential evaluation. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 627–641.

Goren, P. N. (2005). Party identification and core political values. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 881–896.

Goren, P. N. (2007). Character weakness, partisan bias, and presidential evaluation: Modifications and extensions. Political Behavior, 29(3), 305–325.

Guliuzza, F, I. I. I., Reagan, D. J., & Barrett, D. M. (1992). Character, competency, and constitutionalism: Did the Bork nomination represent a fundamental shift in confirmation criteria? Marquette Law Review, 75(2), 409–437.

Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2008). Priming, performance, and the dynamics of political trust. Journal of Politics, 70(2), 498–512.

Hibbing, J. R., & Theiss-Morse, E. (Eds.). (2001). What is it about government that Americans dislike?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hopkins, D. (2015). The upside of accents: Language, inter-group difference, and attitudes toward immigration. British Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 531–557.

Huff, C., & Tingley, D. (2015). Who are these people? Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Research and Politics, 2(3), 1–12.

Johnson, T. R., & Roberts, J. M. (2004). Presidential capital and the Supreme Court confirmation process. Journal of Politics, 66(3), 663–683.

Kagan, E. (1995). Confirmation messes, old and new. The University of Chicago Law Review, 62(2), 919–942.

Kastellec, J. P., Lax, J. R., & Phillips, J. H. (2010). Public opinion and Senate confirmation of Supreme Court nominees. Journal of Politics, 72(3), 767–784.

Kelly, D. E. (2010). Predicting public approval of Supreme Court nominees: Examining factors influencing mass public opinion of stealth nominees in the post-Bork era. Political Science, Iowa State University.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 335–358.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). How voters decide. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis-Beck, M., Jacoby, W. G., Norpoth, H., & Weisberg, H. (2008). The American voter revisited. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109.

Mason, W., & Suri, S. (2012). Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 44(1), 1–23.

Munro, G. D., & Ditto, P. H. (1997). Biased assimilation, attitude polarization, and affect in reactions to stereotype-relevant scientific information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(6), 636–653.

NBC News/Wall Street Journal. (2005). Poll conducted September 9–September 12, 2005 and based on 1,013 telephone interviews.

Nemacheck, C. L. (2008). Strategic selection: Presidential nomination of Supreme Court Justices from Herbert Hoover through George W. Bush. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Overby, L. M., Henschen, B. M., Walsh, M. H., & Strauss, J. (1992). Courting constituents? An analysis of the Senate confirmation vote on Justice Clarence Thomas. American Political Science Review, 86(4), 997–1003.

Paolacci, G., & Chandler, J. (2014). Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), 184–188.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1996). Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary approaches. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Ruckman, P. S, Jr. (1993). The Supreme Court, critical nominations, and the Senate confirmation process. Journal of Politics, 55(3), 793–805.

Segal, J. (1987). Senate confirmation of Supreme Court Justices: Partisan and institutional politics. Journal of Politics, 49(4), 998–1015.

Staff. (2016). Donald Trump says the law is settled on gay marriage but not on abortion. The Economist, November 15, 2016.

Stimson, J. A. (1999). Public opinion in America: Moods, cycles and swings (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Taber, C. S., Cann, D., & Kucsova, S. (2009). The motivated processing of political arguments. Political Behavior, 31(2), 137–155.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769.

Wedeking, J. P., & Farganis, D. (2010). The candor factor: Does nominee evasiveness affect Judiciary Committee support for Supreme Court nominees? Hofstra Law Review, 39(2), 329–368.

Zaller, J. R. (1991). Information, values, and opinion. American Political Science Review, 85(4), 1215–1237.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Vignettes

These are the short biographical vignettes the respondents read before entering the DPTE. The differences, given the different conditions are bolded.

James/Mary Walker is a nominee for the Supreme Court. He was nominated by Benjamin Halston, the current Democratic/Republican president. He enjoys the support of the Current Chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, a Democratic/Republican senator from Kansas.

Reticent Nominee Manipulation

WASHINGTON-DC: Today the Senate Judiciary Committee began its third day of confirmation hearings with Judge James/Mary Walker, President Halston’s nominee to the Supreme Court. Questions today centered on Judge Walker’s judicial philosophy. Many senators asked specific questions about how the judge would rule on important issues that may face the Court in the coming years including issues of gun rights, free speech, detainment of enemy combatants, and the rights of corporations. Keeping with a long-standing tradition, Judge Walker was reticent to answer any questions on cases that could potentially be heard by the Court in the future. While some have praised this decision as respecting important norms of judicial independence, others criticized Judge Walker’s answers today as evasive or even disingenuous. Senator Peter Kimble (I-ME), a member of the Judiciary Committee remarked this afternoon, “how are we supposed to know whether we support him/her if he/she won’t even answer the most basic questions”. Below is a transcript of an exchange today between Kimble and Judge Walker where Kimble pressed Walker on his/her views on gun control.

SENATOR KIMBLE: Judge Walker, your record on the right of the people to bear arms is a bit sparse. You have decided few cases on the issue and I know my constituents are particularly concerned about whether you believe the Second Amendment protects the right to own and carry a firearm. Could you say a bit more about your views?

JUDGE WALKER: Actually, Senator, I know there are several Second Amendment cases in the pipeline that could hit the Court’s docket in the next several years and I am concerned that any answer I give to that question would be a violation of my ethical responsibility to remain impartial in that case. With that in mind, I respectfully decline to say anything more.

SENATOR KIMBLE: You cannot even tell us how you would approach the case? How far you think the Second Amendment extends?

JUDGE WALKER: No Senator, I’m afraid I cannot. It just wouldn’t be ethical.

SENATOR KIMBLE: Can you at least say whether you would follow the established Court precedent that protects the right to a firearm?

JUDGE WALKER: I can say I believe in the Court’s tradition of respecting established precedent. But no, I cannot say whether I, or the rest of the Court would apply any past case to any hypothetical future case.

SENATOR KIMBLE: Well, I guess if you can’t even answer a most basic question like that one, I don’t have anything more. Mr. Chairman, I yield the remainder of my time.

Forthcoming/Conservative Nominee Manipulation

WASHINGTON-DC: Today the Senate Judiciary Committee began its third day of confirmation hearings with Judge James/Mary Walker, President Halston’s nominee to the Supreme Court. Questions today centered on Judge Walker’s judicial philosophy. Many senators asked specific questions about how the judge would rule on important issues that may face the Court in the coming years including issues of gun rights, free speech, detainment of enemy combatants, and the rights of corporations. Breaking with a long-standing tradition, Judge Walker was quite forthcoming about his/her views on cases that could potentially be heard by the Court in the future. While some have praised this decision as refreshingly honest and forthright, others criticized Judge Walker’s answers today as unethical and violating established traditions set to protect the Court’s independence. Senator Peter Kimble (I-ME), a member of the Judiciary Committee remarked this afternoon, “I really appreciated that Judge Walker was willing to express his/her views, even when people on either side may not agree with them.” Below is a transcript of an exchange today between Kimble and Judge Walker where Kimble pressed Walker on his/her views on gun control.

SENATOR KIMBLE: Judge Walker, your record on the right of the people to bear arms is a bit sparse. You have decided few cases on the issue and I know my constituents are particularly concerned about whether you believe the Second Amendment protects the right to own and carry a firearm. Could you say a bit more about your views?

JUDGE WALKER: Of course, Senator. I have long believed the Second Amendment protects a right of the people to keep and bear arms. Any reasonable reading of the Amendment makes clear the Founders intended gun ownership to be a fundamental right.

SENATOR KIMBLE: So how far do you think the Second Amendment extends? May Congress place any limits on gun ownership or possession?

JUDGE WALKER: Well, I’m sure there are probably reasonable limits. And the Court would decide those on a case-by-case basis. But I believe any decision must start from the premise that owning a gun is a fundamental right and we should approach limitations on that right with the highest level of scrutiny.

SENATOR KIMBLE: So you would follow the established Court precedent that protects the right to a firearm?

JUDGE WALKER: I believe in the Court’s tradition of respecting established precedent. And yes, I believe the Court was right in deciding those cases and I would absolutely adhere to that precedent in future cases.

Forthcoming/Liberal Nominee Manipulation

WASHINGTON-DC: Today the Senate Judiciary Committee began its third day of confirmation hearings with Judge James/Mary Walker, President Halston’s nominee to the Supreme Court. Questions today centered on Judge Walker’s judicial philosophy. Many senators asked specific questions about how the judge would rule on important issues that may face the Court in the coming years including issues of gun rights, free speech, detainment of enemy combatants, and the rights of corporations. Breaking with a long-standing tradition, Judge Walker was quite forthcoming about his/her views on cases that could potentially be heard by the Court in the future. While some have praised this decision as refreshingly honest and forthright, others criticized Judge Walker’s answers today as violating established traditions set to protect the Court?s independence. Senator Peter Kimble (I-ME), a Member of the Judiciary Committee remarked this afternoon, “I really appreciated that Judge Walker was willing to express his/her views, even when people on either side may not agree with them.” Below is a transcript of an exchange today between Kimble and Judge Walker where Kimble pressed Walker on his/her views on gun control.

SENATOR KIMBLE: Judge Walker, your record on the right of the people to bear arms is a bit sparse. You have decided few cases on the issue and I know my constituents are particularly concerned about whether you believe the Second Amendment protects the right to own and carry a firearm. Could you say a bit more about your views?

JUDGE WALKER: Of course, Senator. I have long believed the Second Amendment was intended to establish a militia and nothing more. It does not protect the right to own or possess a firearm. Any reasonable reading of the Amendment makes clear the Founders never intended gun ownership to be a fundamental right.

SENATOR KIMBLE: So how far do you think the Second Amendment extends? May Congress place any limits on gun ownership or possession?

JUDGE WALKER: Absolutely. And the Court would decide those on a case-by-case basis. But I believe any decision must start from the premise that owning a gun is a not fundamental right. As such, government restrictions on the privilege of gun ownership are not only constitutional but also probably make for a safer society.

SENATOR KIMBLE: So you would not follow the established Court precedent that protects the right to a firearm?

JUDGE WALKER: While I believe in the Court’s tradition of respecting established precedent, the Court does not get it right every time. And when the Court errs, as it did in these cases, it is the responsibility of future justices to correct the error by overturning that ruling.

Dependent Variables

Feeling Thermometer

Please rate your feelings about the nominee using this slider. 0 indicates you feel very negative about the nominee, 100 indicates you feel very positive about the nominee, and 50 means you feel neither negative nor positive about the nominee.

Support

Based on what you know about the nominee, [James/Mary] Walker, do you currently support or oppose the nominee?

-

Support

-

Oppose

-

Neither Support nor Oppose

-

How strongly or weakly do you [support/oppose] the nominee?

-

Strongly Support/Oppose

-

Moderately Support/Oppose

-

Weakly Support/Oppose

-

Qualification

How qualified do you believe [NOMINEE NAME] is to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court?

-

Completely Qualified

-

Highly Qualified

-

Moderately Qualified

-

Somewhat Qualified

-

Barely Qualified

-

Not Qualified At All

Mechanical Turk and Sample Specifics

While Mechanical Turk is not a nationally representative sample, the convenience sample is useful for experiments in political science. Indeed, the non-representative nature of online opt-in surveys essentially eliminates the ability to generalize results to the population without additional data drawn from representative samples. In particular, the Baker et al. (2010) recommendations urge researchers to avoid panels (like MTurk) “when one of the research objectives is to accurately estimate population values.” We do not disagree with this conclusion, and urge readers to understand our experimental results as working towards uncovering the mechanisms underlying the evaluation of nominees rather than understanding the behavior of the general population. Importantly, Baker et al. (2010) speak to the usefulness of opt-in panels for uncovering underlying public opinion, but do not address the use of these panels for experiments. Thus, while the external validity of experiments conducted on MTurk is relatively low, the internal validity of the study is affected only by the experimental design, not the sample composition.

Additionally, Mechanical Turk has been used extensively in both political science and other behavioral disciplines to answer questions experimentally. These investigations have shown Mechanical Turk samples to be more representative than traditional student or convenience samples and the quality of the data appears to be quite high (Berinsky et al. 2012; Buhrmester et al. 2011; Mason and Suri 2012; Paolacci and Chandler 2014). Furthermore, scholars have used the platform to investigate a number of different psychological and attitudinal traits, including racial resentment and authoritarianism (Craig and Richeson 2014; Crawford et al. 2013; Crawford and Pilanski 2014; Hopkins 2015). Thus, although the subject pool is more liberal, Democratic, and younger than the general population, carefully constructed experiments will not necessarily suffer for these sample deficiencies.

Despite the widespread usage of Mechanical Turk for social science experiments, we would be remiss if we did not address a key demographic issue with these samples. Political knowledge or sophistication is consistently much higher among Mechanical Turk workers than it is in the general population (Berinsky et al. 2012; Huff and Tingley 2015). We do not deny that this bias exists in the Mechanical Turk samples, but we have taken care to minimize its impact. First, by utilizing an experimental approach, differences between conditions are unaffected by sophistication biases in the sample generally. Second, although we believe the tendency of sophisticated individuals to rely on abstract values (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1991; Zaller 1992) makes them more likely to rely on partisanship and less likely to consider new information in their evaluation of nominees, we are sensitive to work that shows sophisticated individuals are more prone to motivated reasoning than those with lower levels of sophistication (Taber and Lodge 2006). Therefore, we again caution readers to interpret our experimental findings primarily as a comparison between conditions, as well as to evaluate the experimental results in concert with our observational results.

Our sample, which consisted of 727 U.S. adults, closely matched Mechanical Turk samples reported in other findings, suggesting that our sample was representative of Mechanical Turk workers (Chen et al. 2014). Our sample was well-educated (62% held at least a 2-year degree), white (83%), Democratic (62% Democratic, 24% Republican, 14% Independent), liberal (54% liberal, 23% conservative, 23% moderate), and young (mean age of 36.4).

Readers are likely to note the noticeable bias towards Democrats and liberals in our sample. While this is typical of Mechanical Turk samples, it does underscore the need to utilize experimental methods with Mechanical Turk. We also note that, although we would like to be able to analyze the independent effects of candor on Democrats/liberals and Republicans/conservatives, the non-representative nature of Mechanical Turk prevents this. Thus, there is some anecdotal evidence to suggest conservatives may be more acceptive of ideological justices than liberals (indeed, President Trump promised a pro-life litmus test for all his Supreme Court nominees, to the satisfaction of the conservative base Staff 2016), we are unfortunately unable to test this proposition with these data.

While the partisan and ideological composition of the sample may at first appear concerning, recall that our experiment utilized prior responses to block individuals into pro- or counter-attitudinal conditions. Thus, one needs not believe that the partisans or ideologues in the sample are representative of the broader population; instead, we only need to believe that the influence of pro- or counter-attitudinal information is similar among Mechanical Turk workers as it is in the general population. Prior research strongly suggests that psychological mechanisms work similarly in both the general and Mechanical Turk populations.

Robustness Check: Single Item Dependent Variables

As noted, we rely on an aggregated index of nominee support in the paper analysis. Nonetheless, we note that the results are not unique to this construction of the dependent variable. If we use the three component pieces of this dependent variable as single-item indicators of support, we see a similar pattern, presented in Table 3.

As Table 3 shows, the same pattern of pro- and counter-attitudinal nominee evaluation occurs for all three variables. In addition, for the feeling thermometer and nominee support variables, we see a significant interaction term between the reticent condition and the counter-attitudinal condition, just as we expected with H2. Only for the question regarding the nominee’s qualifications is the interaction term insignificant. Nonetheless, we are confident in the reliability of our index scale, based on the reliability coefficients and principal-factor analysis reported in the paper.

Robustness Check: Experimental Manipulation Attention Check

We are sensitive to concerns that respondents may not have paid close attention to the experimental manipulation in the DPTE. To assuage these concerns, we can re-run the models with a sample constricted by the amount of time spent reading the experimental manipulation. As Table 4 shows, when comparing the full sample (column 1) to a sample of respondents who spent at least 30 s reading the manipulation (column 2), the results are nearly identical. As we restrict the sample to those who spent less than 30 s with the manipulation (column 3), we see that the interaction term becomes insignificant. If we further restrict the sample to those who spent less than 15 s reading the manipulation (column 4), we see that the interaction term remains insignificant.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, P.G., Bryan, A.C. Judging the “Vapid and Hollow Charade”: Citizen Evaluations and the Candor of U.S. Supreme Court Nominees. Polit Behav 40, 495–520 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9411-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9411-y