Abstract

Immigration enforcement, and deportation in particular, has been shown to have social and psychological effects on the non-deported as well, but its political effects have gone largely unexamined. I use the staggered implementation of Secure Communities, an information-sharing program between the federal government and local law enforcement, to estimate the short-term effects of stricter immigration enforcement on Latino voter turnout. A difference-in-differences analysis indicates that enrollment in Secure Communities led to an increase in county-level Latino voter turnout of 2–3 percentage points. This relatively large effect appears due to greater Latino activism in the wake of program implementation, rather than individuals responding to particular police interactions. These results extend the existing literature on mobilization in response to threat, demonstrate that policies can have far-reaching and unexpected political implications, and suggest that the current immigration debate may have major consequences for the future makeup of the American electorate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The United States has deported over 360,000 people each year since 2008. Research from sociology, law, public health, and other disciplines suggests that these deportations affect the lives of the families, friends, and neighbors deportees leave behind in numerous ways. This paper seeks to test whether deportations, or the policies that permit them, also affect the political lives of citizens who live near potential deportees.

It may seem counterintuitive to study the effects of deportation policy on voters, who by definition are citizens and cannot be deported. However, many Latino citizens live in families or communities with mixed immigration status, so voters could still view enforcement as a threat.Footnote 1 A recent Pew survey found that one in five Latino registered voters (20 %) knew someone who had been deported or detained in the past year. Further, a majority of Latino registered voters surveyed disapproved of the Obama administration’s deportation policies (Lopez et al. 2011). This suggests that a large number of potential voters are being impacted by enforcement policies with which they disagree. For voters in families or neighborhoods that include undocumented residents, the threat or actual experience of seeing their family members, friends, or neighbors face detention or deportation could affect their political behavior. Further, activist mobilization in the wake of policy changes could turn out voters who are not personally aware of them. However, there is little research linking this experience to voter turnout.Footnote 2

This paper seeks to measure the short-term impacts of stricter immigration enforcement measures on Latino voter turnout, using variation in the implementation of the Secure Communities program. I show that this program, which ultimately led to large increases in deportations and removals in counties where it was implemented, also immediately increased Latino voter turnout in treated jurisdictions by several percentage points. I supplement the simplest approach—comparing turnout changes in treated places to those in untreated places—with a quasi-experimental approach that takes advantage of exogenous variation in the timing of program rollout. When I restrict the analysis only to jurisdictions that were not enrolled in the Secure Communities program as of the 2010 general election, as well as those jurisdictions that were enrolled by a state decision rather than any local willingness to participate in the program, the effect remains: Secure Communities enrollment increases Latino voter turnout by several percentage points.

My design isolates the short-term effects of enrollment in Secure Communities, focusing on jurisdictions that were enrolled in the program only a few months before the 2010 election. This limits the direct effects of the program, as very few people would face deportation before the election. Instead, this design allows me to capture just the “threat” effects of Secure Communities, such as voters’ response to hearing about program implementation or activists’ responses to enrollment. I present additional survey evidence that Latino voters in “treated” jurisdictions (those enrolled in Secure Communities by their state) were more likely to be personally asked to vote, and to report turning out to vote, than Latinos in untreated places.

This result contributes to our understanding of how groups can be mobilized in response to threat, demonstrating that political responses can arise even when voters themselves are not the targets of threatening policy. Immigration policy not only has unintended consequences, but has “second-hand” effects on people who were not actually targeted by the policy. These effects appear to be at least partly driven by activist mobilization such as volunteer get-out-the-vote efforts. Although long-term implementation of deportation policies could also have demobilizing effects, there is a reservoir of Latino political power for activists to draw on in the face of such programs.Footnote 3

This finding also adds to our knowledge about immigration enforcement specifically, by demonstrating that this enforcement has political implications. These results would seem to suggest that politicians stake out strict immigration stances at their own peril. But there is an interesting paradox at play: the unprecedented levels of deportation discussed in this paper, and much of the expansion of programs such as Secure Communities, have mainly taken place under a Democratic administration. Many new Latino voters are casting votes for Democrats. The partisan dynamics of immigration enforcement are not straightforward, and this paper raises questions of how immigration policy debates and a growing Latino citizen population will reshape the electoral landscape in the years to come.

Background

Immigration Enforcement as a “Treatment”

Over two million people have been removed from the US since 2008, many of them under the auspices of relatively new police-driven programs such as Secure Communities and 287(g) agreements (Kohli et al. 2011). These federal programs have created, or at least exacerbated, a sense among undocumented residents that they are at risk of detention or deportation whenever they go out in public, and that police officers are now looking for excuses to stop and possibly arrest them (Capps , 2011). If these programs have raised the profile of immigration enforcement actions, greatly increased distrust of government in targeted communities, and created a sense of unfair deportation (of people with families in the US and no history of criminal behavior, for example), then they should have larger effects on political behavior than earlier enforcement actions.

Over the last two decades, immigration enforcement has become more interior-focused, removing many people who are not near any borders and have lived in the U.S. for many years (Waters et al. 2013). These people are more likely to have established family and community ties in the U.S. than recent migrants, and their removal is more likely to affect the political behavior of citizens. Removals have also drastically increased overall: in 1986, there were 24,592 removals, while by 1996 there were 69,680. In 2006, there were 280,974 removals, and in all years since 2007 that number has exceeded 300,000 (US. Department of Homeland Security 2012). Some of these represent repeated deportations of the same individuals, but it still appears that many people are being deported from an increasingly broad geographic area.

One of the programs that have fueled this huge increase in deportations, and the shift from border- to interior-focused enforcement, is the Secure Communities program.Footnote 4 Under Secure Communities agreements, the fingerprints of people arrested by local law enforcement are shared with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and checked against their immigration database. If the arrestee is “removable” (does not have legal status or has a criminal record that includes crimes for which even legal residents are deportable) ICE can then decide whether to issue a detainer and begin removal proceedings (Kohli et al. 2011). This approach means that ICE checks the immigration status of many more people than before. ICE will be able to begin removal procedures for people who previously would have gone unnoticed by agents, such as those that are arrested but are not ultimately imprisoned in the state or federal prisons where agents had been checking inmates’ status. The Secure Communities program was first piloted in several major cities in 2008, and has since been rapidly expanded to include most of the country. It was expected to cover the entire country by the end of 2013 (Hampton and Wade 2012).

The Secure Communities program is expected to have several relevant effects on communities where it is implemented. Most obviously, it will lead to more immigration detention and more deportations in the long term. But other things are likely to happen in the immediate wake of program implementation: the local media (particularly Spanish-language outlets) may report on the program’s implementation, and word may also spread through informal social networks (Hagan et al. 2011). Immigration activists may also publicize the program as a threat to the community, and local churches and civic organizations can provide sites for this publicity, as has happened in the wake of other immigration crackdowns (Hagan et al. 2011). In some places, activists have organized to oppose the program, forming national networks of protesters and holding meetings, rallies, and conferences (Strunk et al. 2013). It is worth considering this entire “treatment” when discussing mechanisms by which the program could affect turnout. This paper focuses on a relatively short window of time between Secure Communities enrollment and the 2010 election, during which the program is unlikely to have led to a large number of completed (or even begun) deportations. Therefore, the main impact of the policy during this time frame will be due to other components of the policy, such as public awareness of enrollment and activist responses to the program.

Immigration Enforcement and Voter Turnout

The literature on Latino voter behavior and turnout contains several results that might predict an increase in turnout after the introduction of a program like Secure Communities, although there is little work on the effects of immigration enforcement in particular. Several studies of Latino turnout in response to threatening policy environments, in particular, have found that contentious policy proposals can lead to changes in political behavior. Barreto et al. (2005) examines voter turnout (among registered Latino voters) in Los Angeles after several years of policy proposals and hostile public discourse targeting Latinos, finding that voter turnout rose over this period. Bowler et al. (2006) argues that ethnically-divisive politics in California during the 1990’s also led to changes in partisanship for both Latino and Anglo voters. The finding that non-Latino voters were affected by policies (such as ending affirmative action and bilingual education) that didn’t directly target them foreshadows this paper’s finding of Latino citizens responding to a policy that targets only noncitizens.Footnote 5 This paper builds on prior work by looking at a new federal immigration policy, using broader geographic data, and focusing on short-term policy effects in the absence of heated rhetoric.

Other related studies focus on first-generation immigrants. Pantoja et al. (2001) suggests that Latino immigrants who naturalized in a state context of threat (California in the 1990’s) were more likely to vote. The naturalization process—and the idea of naturalizing in response to threat—cannot explain this study’s results, as the time frame is too short for immigrants to have responded to policy changes by naturalizing and voting. However, these results are consistent with the idea that people could be mobilized to vote by threatening government action. Similarly, Ramakrishnan (2005) finds that state contexts of threat (measured by discussion of anti-immigrant measures) are associated with higher self-reported turnout by naturalized immigrants of all backgrounds. Because I focus on public records of voting, I cannot address the question of whether first-generation Latino immigrants drive the turnout effect I find among all Latino voters; I do not have information on people’s place of birth. But recently-naturalized immigrants could be more responsive to some of the mechanisms discussed below, and might drive the effects I find. This is especially likely in the realm of immigration policy: Branton (2007) notes that first-generation immigrants prefer less restrictive immigration policies than other Latinos, so they may be more likely to object to the Secure Communities program. Further, Branton et al. (2015) found that responses to the 2006 immigrant rights protests varied by generational status, with first-generation immigrants the most affected. Any such mobilization among first-generation immigrants could vary by citizenship status or national origin (Fraga et al. 2012), as well as political attachments in their country of origin (Wals 2011, 2013).

The studies just described suggest that Secure Communities could increase aggregate voter turnout. There are several mechanisms by which individual voters could be induced to turn out. First, they might respond to the policy of their own accord, either because they see deportations taking place (unlikely in this study), or because they hear about the policy’s implementation. Alternatively (or additionally), voters might be mobilized by activist groups working in response to the policy.

At an individual level, voters could view Secure Communities’ implementation as a threat for a variety of reasons, and respond by turning out to vote. Social psychological theories of protest suggest that the permeability of identity group boundaries is an important determinant of protest behavior (Klandermans 1997). If Latino citizens feel they are being “lumped in” with undocumented Latinos by the Secure Communities program, they could become more likely to identify with potential deportees. They might become more likely to turn out to vote in hopes of changing policy. Indeed, there is some evidence that Latino citizens fear being painted with a broad brush by immigration policy. In the wake of Arizona’s passage of the immigrant-targeting law SB1070, a survey of Latino registered voters in Arizona by the firm Latino Decisions found that 85 % of respondents expected that police would use their power under the law to stop or question legal immigrants or U.S. citizens as well as undocumented immigrants.Footnote 6 Under Secure Communities, people in some areas have been deported after arrests for relatively minor traffic violations, leading activists to claim that they were being pulled over for “driving while Latino” (Ordonez 2011). If Latino citizens feel that the government is singling out Latinos for punitive treatment, that facet of their identity may become more salient, making them more responsive to mobilization efforts by Latino political groups [or simply more likely to vote, as noted by Stokes (2003)]. Footnote 7

A related consideration is whether Latino voters feel “devalued” by the implementation of Secure Communities. Pérez (2015a) draws on social identity theory to predict that elite rhetoric that devalues a racial or ethnic minority group can drive high-identifying members of that group to take political action and push back against the threat to their group. Like the proposed mechanisms of Barreto et al. (2005), Bowler et al. (2006), and Pérez (2015a) predicts that elite rhetoric will threaten and mobilize certain potential voters.Footnote 8 In this research design focused on short-term effects, there is relatively little elite rhetoric: most national- and state-level politicians were quiet about Secure Communities until after the 2010 election, and a national debate about the program flared up only in 2011 when some states tried to opt out of the program. Most people talking about the program in 2010 were either federal employees tasked with implementing it, or local immigration activists seeking to prevent its implementation. However, I posit that even in the absence of elite rhetoric, such a program could politicize Latino identity. The program itself may be seen as discriminatory against Latinos, with voters fearing that the police will target Latinos to arrest, fingerprint, and potentially deport. As such, knowledge of the Secure Communities program could be enough to increase the salience of Latino identity (Armenta et al. 2009) and potentially increase participatory behavior (Cronin et al. 2012).

All of the individual-level mechanisms just described require that potential voters are aware of SC implementation, either from directly observing deportation processes or hearing about the policy. Another set of possible mechanisms centers on the mobilization done by activists in the wake of the policy’s implementation.

The communities in my sample contained a lot of immigration-related organizing potential, both at the grassroots and national levels. Locally, Zepeda-Millan (2014) gives one example of immigrant organizers opposing threatening legislation, describing how members of a soccer club in Fort Myers, Florida became immigration activists during the spring of 2006. Meanwhile, a number of national and regional organizations have begun to focus on political mobilization around immigration issues in recent years (Cordero-Guzman et al. 2008). Groups such as the Hispanic Federation and United We Dream have worked with local activists in a number of states (including Florida and Virginia) to encourage a variety of activities, including voter drives.Footnote 9 In the “treated” states in my sample, groups with an interest in immigration issues, like Virginia New Majority and Democracia Ahora, worked during the 2010 election to mobilize Latino voters.

It is possible that local or state-level activist groups focused on immigrant rights became more active in voter mobilization after SC’s implementation in their area, either because they thought that voting was more important, because they had more active members, or because some national group reached out to them in the wake of the policy’s implementation. This mechanism does not necessarily depend on individual voters’ knowledge of the Secure Communities policy: the turnout effects of voter mobilization efforts such as personal contact have been demonstrated, particularly in the case of Latinos reaching out to mobilize their coethnics (Shaw et al. 2000; Ramirez 2007; Barreto et al. 2009; Bedolla et al. 2012). Latino voters could have turned out more in the wake of SC implementation simply because they were more likely to be asked to do so. The "Possible Mechanisms" section explores the role of activist mobilization.

Data and Methodological Approach

Methodological Approach

The Secure Communities program was first implemented voluntarily in several pilot cities beginning in 2008, and then in other jurisdictions mainly along the southwestern border of the US. Then, ICE sought to gradually expand the program across the country, still focusing on jurisdictions that were willing to voluntarily sign up for the program. This is clearly a source of selection bias: if I simply examined differences in turnout between places with and without the Secure Communities program, my estimates of the causal effect of the program could be biased because places that volunteered to take part in the program might differ in unobservable ways from other places.Footnote 10

However, some jurisdictions received the program without selecting into it. Besides local law enforcement agencies, ICE also negotiated with state law enforcement agencies to try to implement the program across large swaths of the country. Some state-level agencies signed memoranda of agreement (MOAs) with the ICE. Depending on the structure of the state’s law enforcement bodies and databases, some of these MOAs brought all jurisdictions within the state into the program at the same time, without any affirmative action on the part of those jurisdictions. This meant that anyone booked into the county jail in the affected places would have their fingerprints checked against the ICE’s database, without the county government having taken any action to make this happen.

These MOAs mean that some jurisdictions were treated (had the Secure Communities program implemented within their borders) by the time of the 2010 general election without having selected into treatment.Footnote 11 Other jurisdictions in states without such MOAs, who also took no action to enroll in Secure Communities, were left unenrolled. Comparing the “reluctant enrollees” to non-enrolled jurisdictions allows me to find an unbiased estimate of the causal effect of the SC program on Latino turnout for this subset of jurisdictions. I omit from this analysis any jurisdictions that seem to have voluntarily enrolled in the program without state intervention. The remaining number of treated and untreated units appears in Table 1.Footnote 12

I operationalize the treatment of “reluctant enrollment” as follows: for units in the states that opted for universal enrollment (Delaware, Florida, Virginia, Texas, West Virginia), I count units as reluctantly treated if they are in the very last block of jurisdictions to be enrolled in the Secure Communities program. For example, of Florida’s 67 counties, 43 of them were enrolled in the Secure Communities program on June 22, 2010, shortly after the state signed an agreement with ICE. The other Florida counties had already enrolled in the program beginning in 2009, and so are excluded from this analysis due to concerns that they selected into the program and might systematically differ from non-enrollees. In states that did not enroll all jurisdictions in the program (“non-treated” states), I also omit all jurisdictions that voluntarily enrolled in the program by the time of the 2010 general election. Figure 1 shows treated, untreated, and omitted jurisdictions.

I run a simple difference-in-differences analysis, which compares the 2006–2010 change in voter turnout in reluctantly-enrolled jurisdictions to the change in non-enrolled jurisdictions. This requires a parallel trends assumption: if the treated units had not been treated, their Latino voter turnout rates would have followed the same trend as the untreated units actually showed. Thus any difference in the time trends of the two groups is taken to be the treatment effect. However, the identification assumption does not require perfect equivalence between groups: this does not assert that treated and untreated units looked exactly the same before treatment, or that they would have had the same levels of Latino turnout absent treatment, but simply that their trends over time would be the same. I use available data to test this assumption in an Appendix.

This approach allows for a clear causal estimate of the effect of SC enrollment on Latino turnout, but it also restricts the set of places for which the estimate is valid: I am estimating a Local Average Treatment Effect for the places in my sample. However, these places are not a small or unimportant part of the overall picture: my sample contains treated units from states with large Latino populations and ongoing immigration debates, such as Texas and Florida. Table 2 compares the units in my restricted sample to the entire country. The places included are indeed smaller and less dense on average, but they still contain notable Latino populations.

Finally, it is worth noting that all of the “reluctant enrollees” in the sample were enrolled in the program during the summer and fall of 2010. Only a few months elapsed between their enrollment in SC and the 2010 election. As discussed in the literature review, there are reasons to expect that the program could have other impacts over the longer term, as residents observe actual deportations. However, this approach allows me to isolate the short-term political impacts of enrollment, capturing the immediate response of activists and voters in the few months after the program was announced.

Data Sources

Information on the timing of Secure Communities implementation in over 3,000 jurisdictions is drawn from ICE records.Footnote 13 I have also gathered information on the date that state officials signed MOAs with ICE officials.

Estimated Latino vote counts for general elections from 2006 to 2010 are drawn from the Catalist database. Catalist, LLC is a data vendor that collects voter records from each state and maintains a database of nearly 200 million registration records. They merge state voter files with other publicly-available information and commercial information (from advertising databases) to create individual-level records of people’s vote histories and other characteristics. They then use name matching, age, consumer information, and census block demographic data to impute each voter’s racial/ethnic background in states that do not record race in the voter file (Fraga Forthcoming). Their database has reliable vote history data from 2004 onward.

These are vote counts, but in order to calculate voter turnout rates, I need a denominator as well: for this, I use CVAP (citizen voting-age population) estimates of Latino eligible voters from the American Community Survey. Using CVAP estimates for each election year allows me to calculate Latino voter turnout as a percentage of the total number of eligible Latino voters in an area, not just the percent of registered voters that turn out.Footnote 14 This is important because the effect could operate through previously-unregistered people being mobilized to register and vote.

Results

I first present observational results from the entire country, without dropping jurisdictions that may have selected into Secure Communities. Table 3 shows the results of an OLS regression of 2006–2010 change in Latino turnout onto enrollment in Secure Communities (by the time of the 2010 election) and a set of election dummies. These dummies indicate whether there was a senatorial or gubernatorial race on the ballot in the jurisdiction during either of these election years, as these high-profile elections are expected to boost turnout in midterm elections (Smith 2001). This first-cut analysis suggests that enrollment in the Secure Communities program as of the 2010 election led to a greater increase in turnout from 2006 to 2010 than would otherwise have been expected. Even in this basic model, Secure Communities appears to increase voter turnout by about 1.1 percentage points.

Next, I restrict the dataset as discussed above, dropping jurisdictions that selected into the Secure Communities program. The main analysis is conducted on this smaller dataset, estimating a local average treatment effect of the program for these jurisdictions.

The Secure Communities program’s implementation resembles a cluster-randomized natural experiment. The treatment is assigned at the state level, not at the individual counties. So treating each county as an independent unit in the analysis would seriously understate the standard errors of the estimates and make the results look more significant than they truly are (Bertrand et al. 2004). I analyze the data in a more conservative way: I cluster standard errors at the state level, and also run a hierarchical model that allows the intercepts and SC treatment effects to vary by state. Both approaches yield substantively similar and statistically significant results.

Table 4 presents both approaches. The first two columns show estimates from a simple OLS model with robust clustered standard errors. Column 1 displays the simplest specification, regressing the 2006–2010 change in turnout rates onto the treatment variable. Column 2 includes dummy variables for the electoral calendar: whether there was a senatorial or gubernatorial election occurring in each cluster in a given year. Voter turnout varies depending on what races are at the top of the ballot, and states have different schedules for senatorial and gubernatorial elections, so leaving these out makes the parallel-trends assumption about turnout over time somewhat less tenable.

Another approach is to allow the intercept and slope estimates to vary by state.Footnote 15 Columns 3 and 4 of Table 4 present the fixed effects from hierarchical linear models with varying intercepts and slopes, and just varying intercepts, respectively.

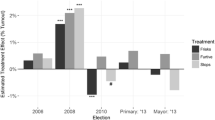

Figure 2 plots the treatment coefficients from both approaches. In both cases, I estimate that the implementation of the Secure Communities program increased Latino turnout in the treated counties by 2–3 percentage points. This is a sizeable effect. Turnout has a possible range of 0 (none of the eligible Latino voters turned out) to 100 % (all eligible voters turned out). The average 2006 Latino turnout rate for all counties in the dataset was 15 %: that is, 15 % of Latino voting-age citizens turned out to vote.Footnote 16 So a turnout increase of 2.4 percentage points in the treated counties (relative to the untreated ones) represents a large jump in turnout. This increase in turnout is comparable to the treatment effect of receiving three pieces of direct mail encouraging one to vote in the classic turnout experiment reported in Gerber et al. 2000).

Stability of Results

These results are consistent under various model specifications and data subsets.Footnote 17 The coefficient estimates from the model presented in column 4 of Table 4 remain quite similar when I drop jurisdictions with very small numbers of Latino residents (all those below 207 eligible voters, the median in the dataset), and are statistically significant at \(p<0.05\). Lower-population jurisdictions may have less reliable population and vote estimates, making the main estimates noisier.

I also restrict the dataset to a smaller set of states where the treatment counterfactual is more conservative. Perhaps some of the untreated places in the dataset could never have been treated due to some unobservable differences in state-level politics, and so they might make a bad comparison group to the treated units. So I restrict to (a) units within states that had at least one jurisdiction enrolled in Secure Communities prior to the 2010 election, and (b) units in states that actually signed a memorandum of agreement with ICE prior to the 2010 election.Footnote 18 In both cases, the logic is that these states didn’t have any clear opposition to the program itself; they were prepared to allow jurisdictions to be enrolled, but some of them didn’t happen to enroll all their jurisdictions at once by the time of the 2010 election. In these limited datasets, the treatment coefficient in the main hierarchical linear model with election covariates remains substantially the same.

The results are also robust to using a more conservative analytic approach on the main dataset, following Green et al. 2007) in aggregating the data to the level at which treatment was assigned. This yields a dataset with 49 state clusters rather than thousands of individual jurisdictions.Footnote 19 Regressing the cluster-level change in Latino turnout from 2006 to 2010 onto the SC treatment variable and the set of election-timing covariates, as in the main analysis (weighted by the number of jurisdictions in each cluster, as in Green et al. (2007)], yields a treatment effect estimate of 2.9 percentage points (p = 0.034).

Next, I ensure that my results are not being driven by one state with poor data or uncommon events. If one of the treated places had a particularly contested 2010 election, or if some of the untreated places had uncharacteristically high Latino turnout in 2006, there could be a difference in 2006–2010 slopes that was not actually due to my treatment. For example, it is possible that Robert Menendez’s 2006 Senate campaign in New Jersey mobilized Latino voters there to turn out to vote at higher-than-average levels, such that 2010’s return to ordinary turnout levels looks like a drop in turnout. In cases like this, my difference-in-difference analyses could find an apparent “treatment effect” even if Latino turnout in treated places were exactly the same before and after Secure Communities implementation.

To address such concerns, Fig. 3 shows the estimated treatment effect (from the preferred specification) when each state cluster is omitted from the analysis. The resulting changes in effect size are minor, suggesting that no one state’s political landscape is driving the results.

Finally, I run a placebo test to make sure that the effect estimated isn’t capturing something else about the 2010 election season. Running the same analysis on a dataset of non-Latino white turnout in the 2006 and 2010 elections does not yield a significant Secure Communities treatment effect. White voters are less likely to feel threatened by the Secure Communities program, are less likely to know deportable immigrants, and are less likely to be targeted by activists seeking to get out the vote in the wake of program implementation. That they do not respond to the Secure Communities “treatment” is reassuring, as it suggests that the Latino effect measured here is in fact threat-related and not spurious. Similarly, Appendix 1 reports results from another placebo test, checking for a treatment effect on Latino turnout prior to the implementation of Secure Communities.

Possible Mechanisms

Secure Communities’ implementation could cause the voter turnout effects shown in Fig. 2 in several ways. First, voters could have direct personal experiences with immigration enforcement, seeing family members or neighbors face deportation. As noted in the introduction, the design of this paper explicitly precludes that possibility by focusing on the immediate effects of the program in places that implemented it only a few weeks or months before the election. In Appendix 2, I provide further evidence that even with fairly generous assumptions about the number of deportations that could have happened in this short period, the number of people directly affected by SC does not seem to predict voter turnout. Comparing places that had high numbers of fingerprint submissions to ICE (the first thing to change after program implementation, and the first step on the path to deportation) to those with low numbers of submissions, I do not observe any difference in treatment effects. If direct personal experiences were driving these effects, we would expect the effects to be concentrated among high-submission places where more fingerprints were submitted and therefore more people could face the threat of eventual deportation. That they are not suggests that something other than direct personal experience with the program is driving the observed treatment effect.

The “threat” mechanisms by which Secure Communities could shape turnout fall into two categories: individual voters’ responses, and activist mobilization. These are not mutually-exclusive: for example, individuals could be aware of the program and feel threatened by it, but not link that to political action until prompted to do so by activists. In this story, both threat and activist mobilization would be necessary for turnout. I cannot fully distinguish between these individual and mobilization mechanisms, as there is no good measure of individual voters’ knowledge of the Secure Communities program at the time of enrollment. However, I can use survey data on mobilization to look for evidence of activists’ role in increasing voter turnout in affected places. In this section, I find that Latino voters in places with Secure Communities were more likely to report being asked to turn out to vote than those in other places.

Survey Data on the “Mobilization” Mechanism

Despite national reports of low interest and projections of low Latino voter turnout in the 2010 midterm elections, there were vigorous on-the-ground voter mobilization efforts in some places, including some of the “treated” jurisdictions in my sample. In central Florida, volunteers with Democracia called Latino voters and encouraged them to turn out.Footnote 20 Mi Familia Vota partnered with other national and local organizations to launch a multistate get-out-the-vote effort that included Texas and Florida.Footnote 21 However, there is little available data on these mobilization efforts, so it is difficult to tell whether they were more likely to take place (or to be successful) in treated areas. Could these efforts have led to the turnout results shown in Fig. 2? For more systematic evidence on voter mobilization, I turn to survey data from the Cooperative Congressional Elections Study (CCES) from 2010.

The question is whether Latino eligible voters in treated jurisdictions were more likely to report being asked to vote than eligible voters in non-treated places. This appears to be the case. Table 5 shows the results of regressing answers to the question “During the November election campaign, did a candidate, party organization, or other organization contact you to get you to vote?” onto various predictors for Latino respondents in 2010.Footnote 22 Results presented are from OLS models, with standard errors clustered at the county level. Column 1 reports the bivariate relationship between living in a place with SC implementation and reporting contact, which is positive and significant. It remains fairly large and marginally significant even when including other factors that should predict activist or campaign contact, like party identification or being a registered voter. Table 6 presents equivalent results for respondents’ self-reported voting behavior in the 2010 general election. In this case, the coefficient estimates are not always statistically significant, but are always positive, again suggesting that Latinos living in counties with Secure Communities in place were more likely to turn out to vote in 2010.

Living in a place where Secure Communities was implemented before the 2010 election was associated (observationally) with more voter mobilization efforts for Latinos in 2010. I ran two placebo tests to make sure that this wasn’t simply due to underlying differences in mobilization across treated and untreated places. I find no comparable effect for Latino CCES respondents in 2006, which is reassuring: the Secure Communities treatment should not have an effect on the 2006 election, as it hadn’t yet happened. I also find no comparable effect (neither substantively nor statistically significant) for non-Latino CCES respondents in 2010. Both these results should give us confidence that the results presented in Table 5 are not simply a coincidence, but are due to specific mobilization of Latinos in the wake of Secure Communities implementation.Footnote 23 These results do not rule out the possible importance of individuals’ “threat” responses (learning about Secure Communities and deciding to vote either without any mobilization, or because of both the policy and the mobilization), but they demonstrate that mobilization is at least one pathway through which the policy affected turnout.

Discussion/Conclusion

This paper finds evidence that Latino voters in places where Secure Communities was implemented turned out more than they would otherwise have been expected to do. This turnout seems to have been accompanied by more contacts asking Latinos to vote. This suggests mobilization in response to threat of a specific kind: people being mobilized by (or in the wake of) policies that by definition did not target them personally. These findings open many avenues for future work.

First, time may yield better data with which to test this process, as more years of data are available to test parallel trends and other immigration enforcement policies emerge. Next, the specific process of mobilization merits close examination. Who asked Latino citizens to turn out in the wake of policy changes? How do places differ in their capacity for this sort of mobilization? What is the role of elite actors in organizing the response to such policies? Finally, when does this result (of increased turnout) hold, and when does it disappear or even reverse? Other punitive or paternalistic policies are associated with diminished turnout, even for those who experience them secondhand (Burch 2013; Weaver et al. 2014; Bruch et al. 2010). Why should the realm of immigration enforcement differ?

The case of immigration enforcement is different from policies like welfare policy or incarceration in several ways. The intervention studied here, the Secure Communities program, was a distinct policy change that affected entire counties at once; work on policy feedbacks of welfare or prison has usually focused on the contact that a specific person or family has with the government, not with major changes in broad policy. Further, deportation policies might be thought to target a less stigmatized population than welfare or incarceration, though this is debatable. Deportation also differs from most policies in that it cannot be expected to happen to voters, no matter what: voters have no reason to fear retaliatory deportation (at least of themselves) if they become politically involved. Finally, the potential voters studied in this paper, Latino citizens across the US, span a wide range of ages, classes, education and income levels. Which of these differences matter most for mobilization have yet to be determined.

These results on immigration policy also have implications for party competition. In the case of Secure Communities, a Democratic president implemented a program that was unpopular with Latino voters, but that actually prompted these voters to turn out at higher rates—and quite possibly to vote for Democrats. This pattern is both counterintuitive and different from the rest of the policy feedback literature. Time will tell whether this pattern of Democratic politicians benefiting from Democrats’ restrictive immigration policies) will persist, with Latino voters becoming increasingly “captured” by the Democratic party (Frymer 1999), or whether the Republican party will be able to successfully compete for Latino votes.

Notes

Latino citizens are not the only ones who could be exposed to fears of deportation second-hand. But it seems like a fairly common experience for Latinos, and focusing on a smaller group rather than all voters makes it easier to see small changes in turnout. Further, Latinos (including registered voters) report highly unfavorable views of deportation, which should make the immigration enforcement “treatment” more straightforward for this group of voters than for others with more mixed views (Lopez et al. 2011).

There is some work linking policy and treatment of Latinos to voter behavior, such as Bowler et al. (2006) and Barreto et al. (2005). But my contention is that immigration policies could be shaping political behavior even in the absence of political rhetoric about one party’s hostility toward Latinos, simply because of actual government actions.

Another such program was the 287(g) program, which trained and deputized local police to perform immigration enforcement duties. Having such a program in place neither prevented nor guaranteed Secure Communities implementation in a city or county.

Other related work focuses on the mobilizing effects of threat on other ethnic groups, such as Cho et al. (2006)’s discussion of high-SES Arab-Americans’ political mobilization after 9/11.

SB1070’s requirement that police determine the immigration status of anyone arrested or detained is broader than the Secure Communities program, but Latino voters could feel targeted nonetheless.

This could shape their vote choice as well as their turnout, which is beyond the scope of this paper. See Bowler et al. (2006) for consideration of partisanship in the face of anti-Latino policies.

Also see Pérez (2015b) for a discussion of how elite rhetoric shapes political trust among Latinos.

These efforts join the GOTV activities of groups focused solely on Latino civic engagement, such as Mi Familia Vota.

As an example: some places might select into the program as a response to growing Latino turnout rates or the expectation of future turnout increases, perhaps because existing political elites felt threatened by growing Latino political power. If this were the case, a simple comparison of turnout rates in treated and untreated places could show a positive “treatment” effect on turnout even if the Secure Communities program did nothing.

I focus here on the 2010 general election because it was the only federal election for which this research design is possible. At the time of the 2008 presidential election, only a handful of jurisdictions had been enrolled in the program as a pilot. By the 2012 presidential election, nearly the entire country was enrolled. Only in 2010 was there useful variation in enrollment.

I also omit about 120 jurisdictions nationwide for which there is not reliable turnout data, due to a combination of incomplete population estimates and missing or unreliable vote data from Catalist. About 80 of these jurisdictions are dropped due to implausible Latino turnout estimates when the two data sources are combined (i.e., over 100 %); the results presented are robust to simply including these places and their estimated turnout. This is a very small proportion of all units in the analysis, and represents places with extremely small Latino populations.

For the purpose of Secure Communities implementation, “jurisdictions” are generally counties, but in some states they may also include county-equivalents, such as the independent cities of Virginia.

Using ACS data provides intercensal estimates, so population estimates can change across the two election years.

One other approach that might otherwise be desirable, adding in state fixed effects, is not possible in this study because there is no within-state variation in treatment in the dataset.

This may seem quite low. Note that this is based on all eligible voters, not just those who have registered. It is also a midterm election, and Latino turnout has been observed to be quite low during midterm elections (Cassel 2002). Validated vote studies that are not prone to the over-reporting problems of survey self-reports find low Latino turnout in both presidential and midterm elections. (Shaw et al. 2000; Cassel 2002)

Regression tables available upon request.

States besides my 5 “treated” states signed MOAs; however, not all units in these other states became enrolled in the program by the 2010 election. This seems to have been due to differences in agreement timing, the structure of state criminal justice information systems, and possibly ICE field office resources.

Arizona does not appear in this dataset because all of its counties were enrolled individually in the SC program before the 2010 election. This does not seem to have occurred as a result of any state action, as in the “treated” states, but simply as a gradual voluntary enrollment.

Source Democracia Ahora’s 2010 election-day liveblog, accessed December 2014 through the Internet Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20101123133606/http://democracia-ahora.org/blog/election_day_live_blog/

For this analysis, I omit responses from jurisdictions that may have selected into the SC program, so my geographic coverage is comparable to the main analysis. That is, responses are included from “reluctant enrollee” counties and unenrolled counties as of the 2010 election.

See Appendix for regression tables.

These estimates are available for about half of the jurisdictions in the main dataset.

For the purposes of this test, I focus on full states, rather than on “state” clusters that omit jurisdictions that selected into the SC program. I think this is more realistic, as treatment was determined at the state level. However, the results do not change substantively if I omit the jurisdictions that voluntarily enrolled in SC, as in the dataset used for the main analysis; there is still no significant relationship between 2002 and 2006 change in turnout and treatment at the state level. Similarly, no significant relationship emerges if I weight the regression by the number of units in the state pre-collapse, or by the cluster’s 2002 Latino population. Finally, no significant relationship emerges if I run the same analysis at the county level rather than the state.

I perform this matching using the “Synth” package for R (Abadie et al. 2011).

It may seem that Texas, the only cluster with a negative point estimate, should be weighted more heavily. But recall that the population used is the Latino population in the cluster after having dropped places that voluntarily selected into the program. Texas’ major population centers were enrolled into the SC program quite early.

This may not be an accurate assumption, but there was no more precise data available on the timing of fingerprint submissions. Still, I use this assumption only to divide the sample into above- and below-median jurisdictions on submissions, so even a rough measure should provide a reasonable division. Further, this analysis is used only to ensure that Secure Communities enrollment is not driving the main results, and this assumption should, if anything, overestimate the number of people who had direct experience with the program prior to the election.

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 493–505.

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2011). Synth: An R Package for synthetic control methods in comparative case studies. Journal of Statistical Software, 42, 1–17.

Armenta, B. E., & Hunt, J. S. (2009). Responding to societal devaluation: Effects of perceived personal and group discrimination on the ethnic group identification and personal self-esteem of Latino/Latina adolescents. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12(1), 23–39.

Barreto, M. A., & Woods, N. (2005). Latino voting in an anti-Latino context. In M. S. Gary & B. Shaun (Eds.), Diversity in democracy: Minority representation in the United States (pp. 148–169). Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Barreto, M. A., & Nuno, S. A. (2009). The effectiveness of coethnic contact on Latino political recruitment. Political Research Quarterly, 64(2), 448–459.

Bedolla, L. G., & Michelson, M. R. (2012). Mobilizing inclusion: Transforming the electorate through get-out-the-vote campaigns. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bertrand, M., Esther, D., & Sendhil, M. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics (October).

Bowler, S., Nicholson, S. P., & Segura, G. M. (2006). Earthquakes and aftershocks: Race, direct democracy, and partisan change. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 146–159.

Branton, R. (2007). Latino attitudes toward various areas of public policy: The importance of acculturation. Political Research Quarterly, 60(2), 293–303.

Branton, R., Martinez-Ebers, V., Carey, T. E., & Matsubayashi, T. (2015). Social protest and policy attitudes: The case of the 2006 immigrant rallies. American Journal of Political Science, 59(2), 390–402.

Bruch, S. K., Ferree, M. M., & Soss, J. (2010). From policy to polity: Democracy, paternalism, and the incorporation of disadvantaged citizens. American Sociological Review, 75(2), 205–226.

Burch, T. (2013). Trading democracy for justice: Criminal convictions and the decline of neighborhood political participation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Capps, R. (2011). Delegation and divergence: A study of 287 (g) state and local immigration enforcement. Technical report Migration Policy Institute.

Cassel, C. A. (2002). Hispanic turnout: Estimates from validated voting data. Political Research Quarterly, 55(2), 391–408.

Cho, W. K. T., Gimpel, J. G., & Wu, T. (2006). Clarifying the role of SES in political participation: Policy threat and Arab American mobilization. Journal of Politics, 68, 977–991.

Cordero-Guzman, H., Martin, N., Quiroz-Becerra, V., & Theodore, N. (2008). Voting With their feet: Nonprofit organizations and immigrant mobilization. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(4), 598–617.

Cronin, T. J., Levin, S., Branscombe, N. R., van Laar, C., & Tropp, L. R. (2012). Ethnic identification in response to perceived discrimination protects well-being and promotes activism: A longitudinal study of Latino college students. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(3), 393–407.

Fraga, Bernard L. N. D. (Forthcoming). Candidates or districts? Reevaluating the role of race in voter turnout. American Journal of Political Science. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/ajps.12172.

Fraga, L. R., Hero, R. E., Garcia, J. A., Jones-Correa, M., Martinez-Ebers, V., & Segura, G. M. (2012). Latinos in the new Millennium: An almanac of opinion, behavior, and policy preferences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frymer, P. (1999). Uneasy alliances. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gerber, A. S., & Green, D. P. (2000). The effects of canvassing, telephone calls, and direct mail on voter turnout: A field experiment. American Political Science Review, 94(3), 653–663.

Green, D. P., & Vavreck, L. (2007). Analysis of cluster-randomized experiments: A comparison of alternative estimation approaches. Political Analysis, 16(2), 138–152.

Hagan, J. M., Rodriguez, N., & Castro, B. (2011). Social effects of mass deportations by the United States government, 2000–2010. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(8), 1374–1391.

Hall, A. B. (2013). Systemic effects of campaign spending. Working Paper. pp. 1–33.

Hampton, W. (2012). Secure communities activated jurisdictions. Technical report. www.ice.gov/doclib/secure-communities/pdf/sc-activated.pdf.

Klandermans, B. (1997). The social psychology of protest. London: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Kohli, A., Peter, L. M. & Lisa, C. (2011). Secure communities by the numbers: An analysis of demographics and due process. The Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Law and Social Policy, pp. 1–20. http://ranid.mc.yu.edu/uploadedFiles/Cardozo/Profiles/immigrationlaw-741/Warren Institute Secure. Communities by the Numbers.pdf.

Lopez, M. H., Gonzalez-Barrera, A., & Motel, S. (2011). As deportations rise to record levels, most Latinos oppose Obama’s policy. http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2011/12/Deportations-and-Latinos.pdf.

Ordonez, F. (2011). ICE rolling out secure communities: New high-tech federal program will replace 287(g) that’s used to identify jailed illegal immigrants. http://docs.newsbank.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info:sid/iw.newsbank.com:AWNB:CHOB&rft_val_format=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&rft_dat=127D2436257395E0&svc_dat=InfoWeb:aggregated5&req_dat=B425E5B32E784515BC5AAA87BC16A340

Pantoja, A. D., Ramirez, R., & Segura, G. M. (2001). Citizens by choice, voters by necessity: Patterns in political mobilization by naturalized latinos. Political Research Quarterly, 54(4), 729–750.

Pérez, E. (2015a). Ricochet: How elite discourse politicizes racial and ethnic identities. Political Behavior, 37, 155–180.

Pérez, E. (2015b). Xenophobic rhetoric and its political effects on immigrants and their co-ethnics. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 549–564.

Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2005). Democracy in immigrant America: Changing demographics and political participation. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Ramirez, R. (2007). Segmented mobilization: Latino nonpartisan get-out-the-vote efforts in the 2000 general election. American Politics Research, 35(2), 155–175.

Shaw, D., de la Garza, R. O., & Lee, J. (2000). Examining Latino turnout in 1996: A three-state, validated survey approach. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 338–346.

Smith, M. A. (2001). The contingent effects of ballot initiatives and candidate races on turnout. American Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 700–706.

Soss, J. (1999). Lessons of welfare: Policy design, political learning, and political action. American Political Science Review, 93(2), 363–380.

Stokes, A. K. (2003). Latino group consciousness and political participation. American Politics Research, 31, 361–378.

Strunk, C., & Leitner, H. (2013). Resisting federal-local immigration enforcement partnerships: Redefining “Secure Communities” and public safety. Territory, Politics, Governance, 1(1), 62–85.

US. Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Inspector General. (2012). 2011 yearbook of immigration statistics. Technical report US Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics Washington, D.C.

Wals, S. C. (2011). Does what happens in Los Mochis stay in Los Mochis? Explaining postmigration political behavior. Political Research Quarterly, 64(3), 600–611.

Wals, S. C. (2013). Made in the USA? Immigrants’ imported ideology andpolitical engagement. Electoral Studies, 32(4), 756–767.

Waters, M. C., & Simes, J. T. (2013). The Politics of Immigration and Crime. Crime and Immigration: In The Oxford Handbook on Ethnicity.

Weaver, V. M., & Amy, E. L. (2014). Arresting citizenship: The democratic consequences of American crime control. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zepeda-Millan, C. (2014). Weapons of the (not so) weak: Immigrant mass mobilization in the US south. Critical Sociology.

Acknowledgments

I thank Asad Asad, Angie Bautista-Chavez, Peter Bucchianeri, Ryan Enos, Julie Faller, Bernard Fraga, Claudine Gay, Adam Glynn, Jennifer Hochschild, Dan Hopkins, Noah Nathan, Kay Schlozman, Rob Schub, and the participants of the Harvard Working Group in Political Psychology, the Harvard Inequality Proseminar, and the Harvard American Politics Research Workshop for helpful comments and thoughts. This research has been supported by a Harvard University Grant from the Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality & Social Policy. Replication data for this paper will be posted no later than April 2016 at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/arwhite.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1:Testing Assumptions/Robustness Tests

Due to the limitations of the Catalist database and the ACS, I do not have reliable voter turnout data for the years prior to 2006, which makes it difficult to test the assumptions of the difference-in-differences setup. However, in this section I present several tests of the assumptions based on the available data. I verify that pre-treatment trends in turnout do not predict treatment, I run a placebo test to demonstrate that my approach does not find treatment effects where none should exist, and I use synthetic matching to address concerns that control units may not be similar enough to treated units.

Checking Pre-treatment Trends

First, we might worry that places that already had steeper growth in Latino turnout might have also received the SC treatment for some reason, such that the effect I observe is not actually driven by immigration enforcement. To test for this possibility, I use the best available data from 2002 and 2006 to check whether the pre-treatment turnout trends predict treatment. I construct 2002 voter turnout data slightly differently than the 2006 and 2010 data; I use CVAP estimates from the 2000 Census because the ACS did not produce estimates of Latino CVAP prior to 2006 (and then interpolate using 2000 Census and 2006 ACS data to produce 2002 estimates).Footnote 24 Further, Catalist began collecting voter files to construct their database in 2006, so it is possible that their turnout data for prior years is incomplete due to people voting and then being removed from the voter rolls before 2006. Both numerator and denominator are biased by an unknown amount, so it is not clear in which direction the turnout estimates will be biased.

Table 7 presents the results of a regression of the treatment variable onto the 2002–2006 change in Latino turnout in each state cluster.Footnote 25 There is no evidence that pre-2006 time trends, at least for the limited period for which there is data, predict treatment.

Next, I use another dataset to verify the parallel-trends assumption. I use Latino citizen voter turnout rates from the Current Population Survey for elections from 1996 to 2006, and check whether these turnout rates predict treatment (enrollment in the Secure Communities Program). This analysis is shown in Table 8.

I calculate Latino citizen turnout rates for each cluster as follows: I restrict the dataset to jurisdictions that are included in my dataset for the above analyses (dropping places in each state that voluntarily enrolled in SC). Then, for each “cluster” (roughly a state, but with self-selected counties dropped), I calculate the percentage of Latino citizens of voting age that report having turned out in the most recent election, using the survey weights provided with the survey. The November CPS supplement asks about the general election that has just taken place, so for some years it is the midterm congressional election, and in others it is the presidential election.

Some clusters contained very few respondents, so the turnout estimates were quite noisy. In Column (1) of Table 8, I have dropped all clusters with fewer than 30 respondents; Column (2) contains all clusters. In both cases, there is no evidence that previous years’ turnout rates predicted treatment, which supports the parallel trends assumption. Figure 4 plots the Latino turnout trends of states with and without treated units.

Placebo Test: 2002–2006

Having constructed Latino turnout estimates from 2002 for some of the jurisdictions from the main dataset, I can also run a placebo test to check whether there is evidence of a “treatment effect” before the treatment actually took place. Table 9 replicates the main analysis in the paper, the models from columns 4 and 5 of Table 4, for the turnout change from 2002 to 2006 instead of 2006–2010. As discussed above, this data covers a limited number of places and is likely an undercount of voters, but is the best data available. I do not find a comparable treatment effect for 2006–2010.

Synthetic Control

Next, I address concerns about the comparability of treatment and control units, and the possibility of extreme counterfactuals, by using synthetic matching (Abadie et al. 2010). I use this approach to construct a “synthetic control” for each of the treated clusters that is a weighted average of other clusters in the dataset.Footnote 26 I use the available pre-treatment data—the change in Latino voter turnout in each cluster from 2002 to 2006—to create matches that should have similar time trends in voter turnout. This process would be improved by the inclusion of more historical turnout data, but even with limited data it serves as a check on the difference-in-differences results.

I draw from the untreated clusters (that is, states without full pre-election SC enrollment, with any voluntarily-enrolled jurisdictions dropped) to construct matches for each of the treated clusters. For each cluster, I then compare the change in Latino turnout from 2006 to 2010 between the treated and synthetic control unit. The difference between these changes is taken as the treatment effect of Secure Communities enrollment. I take the mean of all treated clusters’ estimates to find an overall estimate of 1.4 percentage points. This is slightly lower than the 2–3 percentage points estimated in the main analysis in Table 4, but is in the same direction and is of comparable magnitude. As shown in Table 10, a mean weighted by the 2006 Latino population of each cluster yields a point estimate of 2.9 percentage points, somewhat larger than the main estimate.Footnote 27

The resulting weights for each synthetic match are available on request, and will be included in the online supplemental information. I have not attempted to quantify the uncertainty around the estimate produced via synthetic matching, as it is not immediately clear how to do so with multiple treated units. The results are fairly similar to the OLS estimates presented in the "Results" section, and so I rely on the better-understood OLS standard errors, as do other papers using this approach as a check (Hall 2013).

Appendix 2: Analysis of Record Submissions

One mechanism discussed above was direct experience with deportation: citizens might observe people they know being deported, and change their political behavior in response. This is unlikely to explain my results, as I focus on places that enrolled in the program only a few months before the 2010 election. However, I use available ICE data to ensure that program implementation in those few months does not explain the turnout results presented here.

Relatively few people would have been deported due to the Secure Communities program at the time of the 2010 election, but there is some variation in the number of people whose fingerprints were submitted to ICE to check their immigration status. In this section, I explore whether places with different numbers of fingerprint submissions had different political responses.

To examine whether program implementation affected changes in turnout, I split the treated units into those with high (above-median) and low (below-median) numbers of fingerprint submissions to ICE, and estimate the SC treatment effect in each subset. ICE provided data on submissions from the time of program activation until August 2012, so I adjusted them to reflect the amount of time the program had actually been in effect by the time of the 2010 election. I assumed that submissions were uniform across the time period reported, and simply multiplied the total number of submissions by the fraction of activated time that fell before the 2010 election.Footnote 28 I divided the treated portion of the sample into units that had sent more than 74 (the sample median) records to ICE prior to the 2010 election, and those that had submitted fewer than that. These record submissions represent the upper bound of people who might have faced deportation due to the Secure Communities program in that jurisdiction—not everyone whose fingerprints were submitted would actually have been deported, and very few people were likely deported before the 2010 election.

Table 11 shows the results of this analysis. They support the assertion that personal experiences with deportation do not drive the turnout effects reported in the main paper. If individual people were turning out to vote because someone they knew personally was in danger of deportation, we would expect more record submissions to be associated with more votes and thus a bigger turnout effect. This is decidedly not the case; as seen in Table 3, higher-submission communities do not show a larger treatment effect than low-submission communities.

It should be noted that this is an observational analysis, and we might think that places with many submissions are different from places with few submissions in many other ways that could affect turnout and the way the SC program was implemented and perceived. One such concern is population, but the same pattern of results appears when the analysis is performed with population-adjusted counts of record submissions (submissions per 1,000 residents, or per 1,000 Latino citizens).

Appendix 3: Additional CCES Analysis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

White, A. When Threat Mobilizes: Immigration Enforcement and Latino Voter Turnout. Polit Behav 38, 355–382 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9317-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9317-5