Abstract

In recent years, health-related quality of life (QoL) has been considered an important outcome for clinical management of acromegaly. Poor QoL has been described in acromegalic patients with active disease as well as after endocrine cure. It is known that acromegaly determines many physical problems and psychological dysfunctions that unavoidably impact on patients’ QoL. Moreover, there is evidence that factors, such as radiotherapy or post-treatment GH deficiency also impair QoL in patients diagnosed with acromegaly. Thus, including the assessment of QoL in daily clinical practice has become fundamental to understand the consequences of acromegaly and the impact on the patients’ daily life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acromegaly can cause physical, psychological and social symptoms. Patients with acromegaly report impaired health-related quality of life (QoL), especially during the active phase of the disease [1]. However, QoL may not completely normalize after successful treatment [1]. Indeed, patients with long-term remission of acromegaly show more negative illness perceptions than patients with acute illness (i.e. acute pain or vestibular schwannoma) [2]. Thus, the concept of “cure” in this pituitary disease should incorporate the patients’ subjective perception.

QoL should be an important outcome in clinical practice. QoL outcome gives the clinician information about the patients’ point of view on their wellbeing and normal daily living. Subjects evaluate their QoL taking into account their expectations, standards and goals, as well as emotional, physical and social aspects of their daily life. Thus, QoL depends on how a particular individual feels, responds and functions in daily life.

QoL was initially measured with generic questionnaires, used for general population and any type of disease (i.e., Nottingham Health Profile—NHP-, EuroQoL which includes the EQ-5 Dimensions and a visual analogue scale, Psychological General Well-Being index—PGWBI- or Short-Form 36-SF-36-) [3–8]. More recently, QoL is measured through a disease-generated or—specific questionnaire (AcroQoL) [9]. In both, the patients should evaluate how they self-perceive their general health status through several possible ratings (i.e. excellent, very good, good, slightly bad, poor). Nevertheless, AcroQoL addresses specific issues or complaints of patients with acromegaly, and is therefore more sensitive to changes after surgery, medical treatments or radiotherapy [9]. In fact, disease duration, age, treatment with radiotherapy and presence of joint problems have been negativity correlated with AcroQoL scores [10–12].

Some subtle effects of acromegaly and its treatment on physical and psychological dimensions might go undiagnosed for years. Potential long-lasting effects of GH and IGF-1 on personality, cognition and behaviour have not been considered until recently. Novel instruments to evaluate cognitive function, psychopathological symptoms and the patient’s subjective perception of QoL outcomes have allowed to document residual morbidity in acromegaly. In general, acromegalic patients may show reduced physical and social functioning, limitations in role functioning due to both emotional and physical problems, increased pain and decreased general well-being, as compared with healthy controls [11].

Effects of treatments on QoL

Worse QoL is usually observed in acromegaly patients during the active phase of the disease as compared with the controlled state [9, 10], although biochemical activity (e.g., high IGF-I levels) is often not found to correlate with worse QoL. Successful surgery and/or medical treatment normalize biochemical parameters (GH and IGF-1) and tend to improve general wellbeing. Nevertheless, QoL does not recover completely in most of the patients.

A systematic literature search up to 2014 of 31 papers assessing QoL in patients with acromegaly evidenced that both active and controlled acromegaly reported more impairments in QoL, than healthy controls and reference values, including depressive symptoms and sexual dysfunction (15 studies with a total of 820 patients) (15). Acromegaly and Cushing’s disease had worse QoL than other pituitary adenomas. QoL generally improved after biochemical cure, although frequently normalization did not occur. Somatic factors (e.g., hypopituitarism, sleep characteristics), psychological factors (illness perceptions) and health care environment (rural vs. urban) were identified as negative influencing factors.

Neurosurgery seems to be associated with greater improvement of QoL than medical therapy alone in controlled acromegaly [13]. Although pharmacological treatment improves both acromegaly comorbidities and QoL [14], the chronic need for monthly injections of somatostatin analogs to control the disease has been related with impaired subjective perception of QoL [15]. Even so, a study has shown that adding pegvisomant (but not placebo) to somatostatin analogs in acromegalic patients with normal baseline IGF-1 improved QoL, as measured by AcroQoL and the Patient-Assessed Acromegaly Symptom Questionnaire (PASQ) score [14], suggesting that normal circulating IGF-1 is no guarantee for whole body “normalization”.

Globally, however, the effects of medical therapy on QoL are conflicting; improvement after long-acting Lanreotide in active acromegaly has been reported, as well as after treatment with Pegvisomant, or combination therapy (Pegvisomant/Octreotide-LAR) in patients who reach disease control, but other reports of no change after Octreotide LAR compared to surgery, or after switching from Octreotide LAR to Lanreotide autogel have also been published (for review see 10). Furthermore, no differences were found between naïve patients treated with octreotide LAR and naïve patients treated with Pegvisomant.

Other treatments, like radiotherapy, can reduce wellbeing. Acromegaly patients treated with radiotherapy have low QoL scores, although it is unknown whether this relates to the more aggressive characteristics of the disease, which remains active after surgery and medical therapy [16]. In this prospective follow-up study over 4 years of a homogenous cohort of patients with sustained biochemical control of acromegaly, AcroQoL scores were found to subtly but progressively worsen over time, radiotherapy being the predominant indicator of this progressive impairment in QoL (16). In particular, radiotherapy may influence energy, pain and social isolation (measured by NHP); physical fatigue and reduced activity and motivation (measured by the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory) and physical performance (measured by AcroQoL) [17].

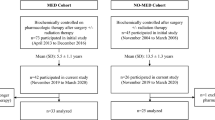

Moreover, development of GH deficiency after treatment of acromegaly also affects QoL. In fact, the patients having the highest QoL were those who attained a normal GH after treatment (i.e., between 0.3 and 1 mcg/L after an oral glucose tolerance test), while higher than normal GH levels (consistent with active disease), or lower (suggestive of GH deficiency), were both associated with more impairment of QoL [18]. Young adult patients who became GH deficient due to prior treatment of acromegaly (with surgery and/or radiotherapy) improved their QoL after substitution therapy with rhGH, but this was not confirmed in older patients [19] (Fig. 1).

In summary, treatment with surgery and pharmacological drugs do improve QoL in acromegaly, but it doesn’t normalize; being aware of this can lead to psychosocial interventions, in addition to optimal medical treatment, aimed at attaining a global improvement in patient outcome.

Effects of physical symptoms on QoL

“Cured” patients with acromegaly have a lower perceived QoL than general population in physical function dimensions on generic questionnaires like SF-36 [19]. Acromegalic patients score worse in the domains of general health, vitality, physical ability and functioning and more bodily pain than patients with non-functioning pituitary adenomas (NFPA) or prolactinomas [17, 20, 21] (Fig. 1).

On the one hand, pain due to joint complaints and musculoskeletal problems has been described in up to 90 % of acromegalic patients [12, 22, 23]. Patients with acromegaly who report bodily pain have worse AcroQoL scores than those without pain [23]. On the other hand, while the presence of headache has also been related with poorer QoL [24], neuropathic pain has been associated with both worse QoL and depression [25].

Effects of psychological symptoms on QoL

Among the factors affecting QoL, psychological status is one of the most relevant. Patients with active disease show more anxiety/depression complaints compared to the other health dimensions of the EuroQoL generic questionnaire [9]. Time elapsed until the diagnosis of acromegaly has been correlated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, reduced psychological QoL, and impaired body image [26].

Body image is an important factor affecting the psychological wellbeing of acromegalic patients. Using the AcroQoL questionnaire, “appearance” has been identified as the most affected dimension [9]. Since changes in appearance persist even after long-term cure, patients with acromegaly usually report self-consciousness about social-, sexual-, bodily- and facial-appearance and show a negative self-concept which has a greater impact on their psychological status and QoL [27].

A recent study has shown that reduction of QoL is driven dominantly by psychopathology (mainly anxiety and depression) rather than other biochemical factors in acromegalic patients [28]. Increased anxiety and depression, maladaptive personality traits and less effective coping strategies have been described in patients with controlled acromegaly, which in turn may affect QoL and cognition [29–31].

Cognitive dysfunction has been identified as a comorbidity in acromegalic patients. When acromegalic patients were asked about their cognitive function, 54 % of those with controlled acromegaly and 57 % with active acromegaly expressed certain degree of cognitive dysfunction [32]. In particular, active acromegalic patients expressed more problems and more severe dysfunction for ability to learn and concentration/distractibility [32]. These cognitive problems can have a negative impact on their daily living (Fig. 1).

Conclusion

QoL measurements should be incorporated in the regular clinical follow-up of patients with acromegaly. Impaired QoL is common in acromegaly, even after successful treatment. Factors that can affect patients’ wellbeing are multidimensional, including physical, psychological, social, demographic and medical dimensions. Clinicians can use QoL outcome to evaluate whether the consequences of the disease negatively impact on patients daily living, as well as to identify patients’ main needs during the management of the disease. Furthermore, patients tend to appreciate being asked about issues frequently not approached in regular follow-ups.

References

Webb SM, Badia X (2016) Quality of life in acromegaly. Neuroendocrinology 103:106–111

Tiemensma J, Kaptein AA, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Biermasz NR (2011) Affected illness perceptions and the association with impaired quality of life in patients with long-term remission of acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:3550–3558

Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, Williams J, Papp E (1981) The Nottingham Health profile: subjective health status and medical consultations. Soc Sci Med 15A:221–229

Gray LC, Goldsmith HF, Livieratos BB (1983) Individual and contextual social-status contributions to psychological well-being. Soc Soc Res 68:78–95

Dolan P (1997) Modelling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 35:1095–1108

Badia X, Herdman M, Schiaffino A (1999) A determining correspondence between scores on the EQ-5D “thermometer” and a 5-point categorical rating scale. Med Care 37:671–677

Brooks R (1996) EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 37:53–57

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M (1993) SF-36 Health Survey. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston

Webb SM, Badia X, Surinach NL (2006) Spanish AcroQoL Study Group: validity and clinical applicability of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire, AcroQoL: a 6-month prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol 155:269–277

Andela CD, Scharloo M, Pereira AM, Kaptein AA, Biermasz NR (2015) Quality of life (QoL) impairments in patients with a pituitary adenoma: a systematic review of QoL studies. Pituitary 18:752–776

Biermasz NK, Van Thiel SW, Pereira AM, Hoftijzer HC, van Hemert AM, Smit JWA, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F (2004) Decreased quality of life in patients with acromegaly despite long-term cure of growth hormone excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5369–5376

Biermasz NK, Pereira AM, Smit JWA, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F (2005) Morbidity after long-term remission for acromegaly: persisting joint-related complaints cause reduced quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2731–2739

Matta MP, Couture E, Cazals L, Vezzosi D, Bennet A, Caron P (2008) Impaired quality of life of patients with acromegaly: control of GH/IGF-I excess improves psychological subscale appearance. Eur J Endocrinol 158:305–310

Neggers SJ, van Aken MO, de Herder WW, Feelders RA, Janssen JA, Badia X, Webb SM, van der Lely AJ (2008) Quality of life in acromegalic patients during long-term somatostatin analog treatment with and without pegvisomant. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3853–3859

Postma MR, Netea-Maiter RT, Van den Berg G, Homan J, Sluiter WJ, Wagenmakers MA, van den Bergh AC, Wolffenbuttel BH, Hermus AR, van Beek AP (2012) Quality of life is impaired in association with the need for prolonged postoperative therapy by somatostatin analogs in patients with acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 166:585–592

Van der Klaauw AA, Biermasz NR, Hoftijzer HC, Pereira AM, Romijn JA (2008) Previous radiotherapy negatively influences quality of life during 4 years of follow-up in patients cured from acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69:123–128

Van der Klaauw AA, Kars M, Biermasz NR, Roelfsema F, Dekkers OM, Crossmit EP, van Aken MO, Havekes B, Pereira AM, Pijl H, Smit WH, Romijn JA (2008) Disease-specific impairments in quality of life during long-term follow-up of patients with different pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol 69:775–784

Kauppinen-Mäkelin R, Sane T, Sintonen H, Markkanen H, Välimäki MJ, Löyttyniemi E, Niskanen L, Reunanen A, Stenman UH (2006) Quality of life in treated patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3891–3896

Wexler T, Gunnell L, Omer Z, Kuhlthau K, Beauregard C, Graham G, Utz AL, Biller B, Nachtigall L, Loeffler J, Swearingen B, Klibanski A, Miller KK (2009) Growth hormone deficiency is associated with decreased quality of life in patients with prior acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:2471–2477

Johnson MD, Woodburn CJ, Vance ML (2003) Quality of life in patients with a pituitary adenoma. Pituitary 6:81–87

Rowles SV, Prieto L, Badia X, Shalet SM, Webb SM, Trainer PJ (2005) Quality of life (QoL) in patients with acromegaly is severely impaired: use of a novel measure of QoL: acromegaly quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3337–3341

Wassenaar MJ, Biermasz NR, Kloppenburg M, van der Klaauw AA, Tiemensma J, Smit JW, Pereira AM, Roelfsema F, Kroon HM, Romijn JA (2010) Clinical osteoarthritis predicts physical and psychological QoL in acromegaly patients. Growth Horm IGF Res 20:226–233

Miller A, Doll H, David J, Wass J (2008) Impact of musculoskeletal disease on quality of life in long-standing acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 158:587–593

Mangupli R, Camperos P, Webb SM (2014) Biochemical and quality of life responses to octreotide-LAR in acromegaly. Pituitary 17:495–499

Dimopoulou C, Athanasoulia AP, Hanisch E, Held S, Sprenger T, Toelle TR, Roemmler-Zehrer J, Schopohl J, Stalla GK, Sievers C (2014) Clinical characteristics of pain in patients with pituitary adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol 171:581–591

Siegel S, Streetz-van der Werf C, Schott JS, Nolte K, Karges W, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I (2013) Diagnostic delay is associated with psychosocial impairments in acromegaly. Pituitary 16:507–514

Roerink SH, Wagenmakers MA, Wessels JF, Sterenborg RB, Smit JW, Hermus AR, Netea-Maier RT (2014) Persistent self-consciousness about facial appearance, measured with the Derriford appearance scale 59, in patients after long-term biochemical remission of acromegaly. Pituitary 18:366–375

Geraedts VJ, Dimopoulou C, Auer M, Schopohl J, Stalla GK, Sievers C (2015) Health outcomes in acromegaly: depression and anxiety are promising targets for improving reduced quality of life. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5:229

Tiemensma J, Kaptein AA, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Biermasz NR (2011) Coping strategies in patients after treatment for functioning or nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:964–971

Sievers C, Ising M, Pfister H, Dimopoulou C, Schneider HJ, Roemmler J, Schopohl J, Stalla GK (2009) Personality in patients with pituitary adenomas is characterized by increased anxiety related traits: comparison of 70 acromegalic patients to patients with non-functioning pituitary adenomas and age and gender matched controls. Eur J Endocrinol 160:367–373

Crespo I, Santos A, Valassi E, Pires P, Webb SM, Resmini E (2015) Impaired decision making and delayed memory are related with anxiety and depressive symptoms in acromegaly. Endocrine 50:756–763

Yedinak CG, Fleseriu M (2014) Self-perception of cognitive function among patients with active acromegaly, controlled acromegaly, and non-functional pituitary adenoma: a pilot study. Endocrine 46:585–593

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crespo, I., Valassi, E. & Webb, S.M. Update on quality of life in patients with acromegaly. Pituitary 20, 185–188 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-016-0761-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-016-0761-y