Abstract

Introduction

Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle is a rare and recently described tumor characterized by a unique histomorphology and exclusive association with the suprasellar/third ventricular compartment. Its clinical, radiological and histological features may vary. Despite the fact that chordoid glioma is a low-grade tumor, its prognosis has been relatively poor because of its insidious presentation and the difficulty in obtaining complete surgical resection.

Materials and methods

Here, we report on a new case of chordoid glioma occurring in a 48-year-old woman, presented with hyponatremia, and on the initial work-up with a diagnosis of hyponatremia due at least in part to SIADH. We review the current literature on this rare pathology, discuss the radiological and histopathologic findings, and discuss the optimal management of chordoid glioma in general.

Conclusion

Based on this new case and the previous literature reports, we suggest that chordoid glioma should be included in the differential diagnosis of uncommon masses of the third ventricle, especially in middle-aged women, and we emphasize current management guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chordoid glioma is a rare central nervous system neoplasm, typically located in the anterior portion of the third ventricle. It was first reported by Brat et al. [1] as a new distinct histopathologic tumor entity and World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 classification assigned it as a grade II neoplasm [2]. Its histogenesis is still uncertain, but a common hypothesis supports a glial origin, specifically from the ependymal cells [3], although other studies have favored divergent neuronal and glial differentiation. Recently, Bielle and colleagues reported thyroid-transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) expression in a series of chordoid gliomas, suggesting an origin from the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis [4]. Clinical, radiological and histological features of chordoid gliomas are pleomorphic and may mimic other types of lesions. The most common clinical presentations are headache, and visual and memory disturbance, but an endocrine presentation is rare [5]. We now report a case of a patient presenting with the syndrome of hyponatremia due at least in part to the inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) which was found to be secondary to a chordoid glioma of the third ventricle, and use this to review the diagnosis and management strategies of this rare tumor. We performed a PubMed search, including English language publications only, using the following key words: chordoid glioma and chordoid glioma of the third ventricle.

Case report

A 48 year-old woman presented with a recent and worsening history of mild fatigue and thirst. Over several months she developed mild polydipsia (c. 2.5 L/day, previously 1–1.5 L/day) and polyuria, as well as the novel onset of nocturia, once a night. She also suffered from intermittent morning headache. Her primary care physician excluded diabetes mellitus, but noted a serum sodium level of 122 mmol/L, which increased to 129 mmol/L after 1 week on fluid restriction of 1 L/day.

The patient was then referred to our institution; she was a non-smoker and non-alcohol user, on no medication, and had no significant past medical history, while there was a positive family history of lung carcinoma. She showed a normal mood and cognition, and there was no obvious memory disturbance. She denied visual problems and galactorrhea, but her menstruation had ceased 2 years earlier.

General physical and specific neurological examination was unremarkable. Her weight was steady (91 kg), blood pressure 140/85 mmHg, and she was clinically euvolemic. Her visual fields were normal to confrontation.

Her laboratory results showed a serum sodium level of 125 mmol/L, a low total serum osmolality (264 mOsm/kg) with a concomitant urine osmolality of 239 mOsm/Kg. The urinary sodium concentration was 47 mmol/L. These laboratory results were considered to be consistent with SIADH. For the definitive diagnosis of SIADH, severe hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency and renal failure were excluded (Table 1). A plain chest x-ray did not reveal any suspected lung mass or pathology.

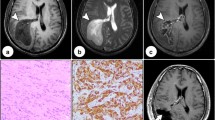

She underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which revealed a 2.3 × 1.6 cm avidly-enhancing mass involving the third ventricle. This appeared to be arising from the right side of the floor of the third ventricle. The mass had areas of low and high signal on T2-weighted images and had a predominantly intermediate signal on T1-weighted images. There were areas of cystic change. The diffusion characteristics were similar to grey matter. The lesion appeared to be separate from the pituitary. Neither hydrocephalus nor any convincing secondary lesions were detected (Fig. 1).

The MR images were discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting and it was considered that this was a tumor arising from the third ventricle, and it was unlikely to be either a craniopharyngioma or a pituitary adenoma; a biopsy was recommended.

The patient underwent a transcranial image-guided endoscopically-assisted biopsy of the third ventricular mass. The macroscopic report showed beige-colored tissue fragments of 3 × 3 × 2 mm. The sample contained parts of a moderately cellular tumor showing a prominent chordoid pattern of differentiation. The tumor cells were moderately pleomorphic with oval/elongated nuclei, evenly distributed, with slightly vesicular chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm. In some areas the tumor cells were epithelioid while in others they showed fibrillary cytoplasm. The background matrix was mucinous (highlighted by ABPAS staining). No mitotic figures were seen. There were prominent plasma cells, some of which contained cytoplasmic Russell bodies. The lesion showed relatively diffuse positivity for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and focal positivity for CD34; there was focal positivity for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and strong positivity for Cam5.2. TTF-1 showed strong nuclear positivity. The Ki-67 proliferative index was low (1–2 %). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of chordoid glioma of the third ventricle (WHO grade II) was made (see Fig. 2).

Representative photomicrographs of the tumor a–f. a Haematoxylin and eosin stain showing chordoid growth pattern of the tumor with epithelioid and fibrillary areas, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation at the centre and a prominent Russell body (yellow arrow); b Blue mucinous background matrix highlighted on Alcian Blue/PAS; c GFAP immunopositivity of tumor cells; d Cytokeration (Cam5.2) immunopositivity of tumor cells; e Focal CD34 immunopositivity of tumor cells; f TTF-1 immunostaining labels tumor cell nuclei

The patient subsequently underwent a transcortical debulking of the third ventricular lesion, which again confirmed the diagnosis of a chordoid glioma.

At 10 weeks post-craniotomy follow-up, the patient was well with normal visual fields. The laboratory findings were: serum sodium 128 mmol/L, serum osmolality 266 mOsm/kg, urine osmolality 234 mOsm/kg, urine sodium concentration 24 mmol/L; serum TSH 0.93 mU/L, FT4 10.0 pmol/L (10.5–20 pmol/L). Serum prolactin, IGF-1 and cortisol were normal (Table 1).

The patient was advised to start thyroxine and to continue with a modest fluid restriction of 2L daily. MRI showed stable residual disease after a further 9 and 12 months, with normalization of her serum sodium. She shows no evidence of other endocrine defects apart from secondary hypothyroidism (Table 1). Informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish her case.

Discussion

Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle is a rare, slow-growing, central nervous system neoplasm, whose definition as a distinct histological entity has only recently been established. To date, it has no known risk factors or syndromic associations. It is reported to occur predominantly in adults, with a mean age of 46 years, with a female predominance of 2:1 [5]. Its localization is usually in the anterior part of the third ventricle with variable extension to the suprasellar region and lateral ventricles.

The initial presentation of chordoid glioma varies from an asymptomatic or incidental detection [6] to an aggressive tumor, but metastatic spread has not been described [7]. The delay from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis is highly variable, depending more on tumor location rather than size [8]. Clinical presentation is usually with multiple symptoms rather than with one presenting feature, although visual disturbance is the most common single symptom [5]. Headache, visual problems and memory impairment are the most reported presenting symptoms of chordoid glioma. Less frequent findings are endocrine dysfunction, including amenorrhea, hypothyroidism and polydipsia [9]. Focal neurological deficits have also been reported, and hydrocephalus was found in nearly 25 % of patients.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of chordoid glioma presenting with SIADH, a disorder of impaired water excretion caused by the inability to suppress the secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) [10]. As is well established, causes of SIADH are multiple and, having excluded any obvious medication [11] or malignancy, our patient underwent brain MRI. Surprisingly, we found SIADH to be secondary to a chordoid glioma.

Clinical features of SIADH are non-specific, and depend upon the absolute serum sodium level and its rate of development. Our patient presented with mild and likely long-standing hyponatremia and without any severe condition related to low serum sodium such as seizure, coma or cardio-respiratory distress. She also denied clinical features of hyponatremia, including nausea, headache, lethargy or cognitive defects. Laboratory investigations showed hypotonic hyponatremia (Na <130 mmol, serum osmolality <275 mOsm/kg), and an inappropriately high urine osmolality (>100 mOsmol/kg) and urinary sodium concentration (>20 mmol/l), suggesting SIADH as the diagnosis [12]. However, she presented with mild polydipsia and mild polyuria, classically not features of SIADH. Thirst sensation and water status are regulated by the central nervous system. The organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, located in the anteroventral part of the third ventricle, is a principal component of the fluid regulation pathway and detects the hypertonicity of blood and orchestrates a state of thirst [13]. We speculate that the presence of unusual polydipsia in the context of SIADH condition could be due to disordered thirst perception. Indeed, the position of the chordoid glioma is close to the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. We might also speculate that the urine osmolality and the urine sodium concentration were not as high as usually seen in SIADH, given the diluition effect secondary to the increased thirst perception and water intake.

MRI of the brain with gadolinium is the best diagnostic imaging tool for the evaluation of chordoid glioma. Usually, this tumor appears to be well-demarcated and oval in shape, with T2 images showing a hyperintense third ventricular mass with uniform enhancement. A cystic component, which was present in our patient’s MR images, is less common, and calcification is rare [14–16].

Radiological differential diagnoses include a broad-spectrum of tumors affecting the suprasellar region [17]; however, the patient’s age, gender, presenting symptoms and any underlying conditions may help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Given the neuroimaging and the unusual clinical presentation of SIADH, our patient underwent a biopsy in order to plan relevant management.

The typical histologic findings consist of epithelioid cells arranged in cords and clusters, embedded in a mucinous matrix rich in lymphoplasmacellular infiltrates and Russell bodies [18, 19]. Mitotic activity is negligible, and neither microvascular proliferation nor necrosis is commonly detected [20, 21]. Similar to the reported cases in the literature, the tumor cells in our case were found to be positive for GFAP, an intermediate filament protein that is expressed by numerous cell types of the central nervous system including ependymal cells, and for EMA. CD34, S-100, vimentin and cytokeratin are also frequently expressed. Due to the expression of CD34, it was speculated that a proportion of chordoid glioma might have neural differentiation. Interestingly, TTF-1 is also positive in this tumor [4]. Synaptophsin, p53 and neurofilament protein are rarely positive. This tumor has low mitotic activity with Ki-67 values typically below 5 % [19].

Treatment strategies and clinical outcomes of chordoid glioma are not well established. Complete surgical resection appears to be the treatment of choice, although proximity to vital central nervous system structures increases the possibility of significant morbidity [22]. Diabetes insipidus, hypothalamic disturbance and memory disturbance are the most frequent post-operative complications. Incompletely resected chordoid gliomas continue to enlarge slowly and some patients experience a poor outcome [23, 24]. Furthermore, a period of rapid tumor enlargement in patients under surveillance has been reported [22, 25, 26], and thus a conservative approach is generally not recommended. Others have suggested that less invasive microsurgery with or without gamma knife radiosurgery [27] can provide a safe and effective treatment for chordoid glioma. Our patient underwent a less aggressive surgical approach without postoperative complications, but careful follow-up is mandatory. At 1 year follow up the residual tumor appears stable. In the event of significant recurrence the choice will be between further surgery, ideally trans-sphenoidal if possible, or some form of radiotherapy.

Conclusions

Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle constitutes a rare, recently recognized primary brain tumor. Despite its generally slow-growth, treatment-related morbidity of chordoid glioma is very high. Clinical and radiological presentations may be heterogeneous and the history may be insidious. It may be that earlier recognition and a more cautious surgical approach may improve outcomes. As we report, SIADH can be secondary to unexpected conditions and a cause for SIADH should always be sought, especially in younger patients.

References

Brat DJ, Scheithauer BW, Staugaitis SM, Cortez SC, Brecher K, Burger PC (1998) Third ventricular chordoid glioma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 57(3):283–290

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114(2):97–109

Leeds NE, Lang FF, Ribalta T, Sawaya R, Fuller GN (2006) Origin of chordoid glioma of the third ventricle. Arch Pathol Lab Med 130(4):460–464

Bielle F, Villa C, Giry M, Bergemer-Fouquet AM, Polivka M, Vasiljevic A, Aubriot-Lorton MH, Bernier M, Lechapt-Zalcman E, Viennet G, Sazdovitch V, Duyckaerts C, Sanson M, Figarella-Branger D, Mokhtari K, RENOP (2015) Chordoid gliomas of the third ventricle share TTF-1 expression with organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. Am J Surg Pathol 39(7):948–956

Desouza RM, Bodi I, Thomas N, Marsh H, Crocker M (2010) Chordoid glioma: ten years of a low-grade tumor with high morbidity. Skull Base 20(2):125–138

Gallina P, Pansini G, Mouchaty H, Mura R, Buccoliero AM, Di Lorenzo N (2007) An incidentally detected third ventricle chordoid glioma. Neurol India 55(4):406–407

Jung TY, Jung S (2006) Third ventricular chordoid glioma with unusual aggressive behavior. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 46(12):605–608

Pomper MG, Passe TJ, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW, Brat DJ (2001) Chordoid glioma: a neoplasm unique to the hypothalamus and anterior third ventricle. Am J Neuroradiol 22(3):464–469

Dziurzynski K, Delashaw JB, Gultekin SH, Yedinak CG, Fleseriu M (2009) Diabetes insipidus, panhypopituitarism, and severe mental status deterioration in a patient with chordoid glioma: case report and literature review. Endocr Pract 15(3):240–245

Frouget T (2012) The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. Rev Med Interne 33(10):556–566

Ramos-Levi AM, Duran Rodriguez-Hervada A, Mendez-Bailon M, Marco-Martinez J (2014) Drug-induced hyponatremia: an updated review. Minerva Endocrinol 39(1):1–12

Grant P, Ayuk J, Bouloux PM, Cohen M, Cranston I, Murray RD, Rees A, Thatcher N, Grossman A (2015) The diagnosis and management of inpatient hyponatraemia and SIADH. Eur J Clin Invest 45(8):888–894

Bourque CW (2008) Central mechanisms of osmosensation and systemic osmoregulation. Nat Rev Neurosci 9(7):519–531

Glastonbury CM, Osborn AG, Salzman KL (2011) Masses and malformations of the third ventricle: normal anatomic relationships and differential diagnoses. Radiographics 31(7):1889–1905

Rees JH (2010) Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle. In: Osborn AG, Salzman KL, Barkovich AJ (eds) Diagnostic imaging: brain, 2nd edn. Lippincott Wiliams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 56–57

Smith AB, Smirniotopoulos JG, Horkanyne-Szakaly I (2013) From the radiologic pathology archives: intraventricular neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 33(1):21–43

Grand S, Pasquier B, Gay E, Kremer S, Remy C, Le Bas JF (2002) Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: CT and MRI, including perfusion data. Neuroradiology 44:842–846

Reifenberger G, Weber T, Weber RG, Wolter M, Brandis A, Kuchelmeister K, Pilz P, Reusche E, Lichter P, Wiestler OD (1999) Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: immunohistochemical and molecular genetic characterization of a novel tumor entity. Brain Pathol 9(4):617–626

Horbinski C, Dacic S, McLendon RE, Cieply K, Datto M, Brat DJ, Chu CT (2009) Chordoid glioma: a case report and molecular characterization of five cases. Brain Pathol 19(3):439–448

Ni HC, Piao YS, Lu DH, Fu YJ, Ma XL, Zhang XJ (2013) Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: four cases including one case with papillary features. Neuropathology 33(2):134–139

Takei H, Bhattacharjee MB, Adesina AM (2006) Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: report of a case with cytologic features and utility during intraoperative consultation. Acta Cytol 50(6):691–696

Vanhauwaert DJ, Clement F, Van Dorpe J, Deruytter MJ (2008) Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle. Acta Neurochir 150(11):1183–1191

Kurian KM, Summers DM, Statham PF, Smith C, Bell JE, Ironside JW (2005) Third ventricular chordoid glioma: clinicopathological study of two cases with evidence for a poor clinical outcome despite low grade histological features. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 31:354–361

Jung TY, Jung S (2006) Third ventricular chordoid glioma with unusual aggressive behavior. Neurol Med Chir 46:605–608

Raizer JJ, Shetty T, Gutin PH, Obbens EA, Holodny AI, Antonescu CR, Rosenblum MK (2003) Chordoid glioma: report of a case with unusual histologic features, ultrastructural study and review of the literature. J Neurooncol 63(1):39–47

Kawasaki K, Kohno M, Inenaga C, Sato A, Hondo H, Miwa A, Fujii Y, Takahashi H (2009) Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: a report of two cases, one with ultrastructural findings. Neuropathology 29:85–90

Kobayashi T, Tsugawa T, Hashizume C, Arita N, Hatano H, Iwami K, Nakazato Y, Mori Y (2013) Therapeutic approach to chordoid glioma of the third ventricle. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 53(4):249–255

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Calanchini, M., Cudlip, S., Hofer, M. et al. Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle: a patient presenting with SIADH and a review of this rare tumor. Pituitary 19, 356–361 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-016-0711-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-016-0711-8