Abstract

Morally speaking, what should one do when one is morally uncertain? Call this the Moral Uncertainty Question. In this paper, I argue that a non-ideal moral theory provides the best answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question. I begin by arguing for a strong ought-implies-can principle—morally ought implies agentially can—and use that principle to clarify the structure of a compelling non-ideal moral theory. I then describe the ways in which one’s moral uncertainty affects one’s moral prescriptions: moral uncertainty constrains the set of moral prescriptions one is subject to, and at the same time generates new non-ideal moral reasons for action. I end by surveying the problems that plague alternative answers to the Moral Uncertainty Question, and show that my preferred answer avoids most of those problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

We’re often uncertain about what our moral commitments should be. And sometimes, we must decide how to act before we can resolve our moral uncertainty. This paper defends a new account of the moral norms that apply to morally uncertain people. That is, this paper answers the question: Morally speaking, what should one do when one experiences moral uncertainty?Footnote 1 Call this the Moral Uncertainty Question. I argue that we shouldn’t answer the Moral Uncertainty Question by appealing to extant “subjectivist” or “objectivist” moral theories. Instead, we can provide a better answer that rests on a non-ideal moral theory. According to the non-ideal moral theory I propose, all moral prescriptions—even non-ideal prescriptions generated by moral uncertainty—are objective, and thus my answer to the Question counts as an “objectivist” answer. However, my objectivist answer is different from other objectivist answers on offer. This non-ideal theory gives us an elegant, unified account of the moral demands made of imperfect agents, including morally uncertain agents.

In Sect. 1, I present a non-ideal theory that rests on a strong ought-implies-can principle: morally ought implies agentially can (OIAC). We should accept this principle, I argue, because a moral theory must respect it in order to prescribe full-fledged actions to actual moral agents. I end the section with an overview of the structure of the non-ideal moral theory I favor.

In Sect. 2, I present an argument for the claim at the core of this paper: that morally uncertain agents are often subject to non-ideal moral prescriptions. If this claim is correct, then a morally uncertain agent sometimes morally ought to behave differently than an agent who has perfect moral knowledge. After presenting my main argument, I provide a more detailed description of the types of non-ideal prescriptions generated by moral uncertainty. I end this section with a discussion of how a moral theory that respects OIAC allows us to give an answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question that satisfies (or at least semi-satisfies) two different criteria for assessing answers to that Question.

In Sect. 3, I survey several other types of answers to the Moral Uncertainty Question, and show that my answer avoids most of the problems that plague other answers.

Finally, in Sect. 4, I respond to an objection. One might worry that my account entails that morally ignorant agents—agents who hold false moral beliefs, and do not experience uncertainty—ought to behave horribly. The proper response to this objection ultimately depends on our axiological commitments, and depends on the details of the morally ignorant agent’s psychology. However, I argue that given some plausible axiological and psychological assumptions, my account does not entail that typical real-life morally ignorant agents ought to act horribly.

1 A non-ideal theory

A non-ideal moral theory, as I’m using the term, is a moral theory that allows the imperfections of an agent to play a role in determining what the agent morally ought to do.Footnote 2 The prescriptions of an ideal moral theory, by contrast, are mostly insensitive to an agent’s imperfections. In this section of the paper, I motivate the claim that an adequate moral theory is a non-ideal moral theory.

1.1 Morally ought implies agentially can

To begin, let me highlight an assumption, which expresses several desiderata for a moral theory:

Assumption: an adequate moral theory reliably prescribes full-fledged actions (and only full-fledged actions) to moral agents in most actual contexts.

Two points of clarification are in order. First, this assumption expresses the idea that an adequate moral theory reliably “applies to us.” When a moral theory prescribes an action to an agent in a context, the theory delivers a deontic verdict about that action.Footnote 3 A deontic verdict about an action expresses that action’s deontic status. Philosophers disagree about which kinds of deontic statuses exist,Footnote 4 but paradigm cases of deontic statuses include obligatory, forbidden, and permitted. A moral theory should reliably—across most contexts—assign deontic statuses to the actions that are available to us agents; if it doesn’t, then the theory doesn’t reliably issue verdicts about what we morally ought to do. I assume that an adequate moral theory usually has something to say about how we morally ought to behave.

Second, this assumption expresses the idea that an adequate moral theory prescribes only “full-fledged actions” to agents. A full-fledged action is an action that results from an uncompromised exercise of one’s agency. Conversely, a compromised action is an action that results from compromised agency. Although I haven’t yet explained the notion of “compromised agency,” we can already see that this second feature of the assumption is well-motivated, in two different ways. First, a person’s agency is the feature in virtue of which a moral theory’s prescriptions apply to that person. So, if a moral theory prescribes compromised actions, then it prescribes that the feature in virtue of which its prescriptions apply be compromised. Such a demand is self-defeating, and suggests that the moral theory is inadequate.Footnote 5 Second, compromised actions are actions that one cannot perform by merely exercising one’s agency, and it’s plausible that such actions are deliberatively irrelevant. If a moral theory prescribes actions that one can perform only if one’s agency is first compromised in some way, then that theory is deliberatively irrelevant from one’s perspective, and is even irrelevant from the perspective of a third party deliberating about what one ought to do.Footnote 6 Thus, I assume that an adequate moral theory does not prescribe compromised actions.

In order for a moral theory to accommodate this assumption—that is, in order for a moral theory to prescribe only full-fledged actions to actual agents—the theory must respect a strong ought-implies-can principle:

Morally ought implies agentially can (OIAC): one morally ought to \(\phi\) only if one agentially can \(\phi\).

Roughly, an action, \(\phi\), is “agentially possible” for an agent when the agent can \(\phi\) as a full-fledged action. But what, exactly, is a “full-fledged” action? And what is a “compromised” action? The difference between a full-fledged action and a compromised action is that a full-fledged action does not rely on an intervening event—an event external to the agent that affects how the agent acts—whereas a compromised action requires an intervening event.Footnote 7Footnote 8 Here’s a paradigm case of a compromised action: I raise my arm, but only as a result of an involuntary muscle spasm. In this case, the action I perform—arm-raising—is compromised, because it relies on an intervening event, namely, an involuntary muscle spasm.

It might be tempting to think that all intentional actions are full-fledged actions. After all, it’s tempting to think that had I raised my arm intentionally, and not as the result of an involuntary muscle spasm, then my arm-raising would have been a full-fledged exercise of agency. However, sometimes even intentional actions are compromised. Consider, for example, a case in which I receive an electric shock; the shock jumbles my beliefs and desires, and as a result I form an intention to raise my arm (and I then follow through on that intention). Even in this case, I do not count as performing a full-fledged action; I form my intention as a result of being shocked (an intervening event), and not as a result of exercising my agential abilities. So, to perform a full-fledged action one must form an intention, and one must form that intention through the exercise of one’s agency. Agency, I take it, is the ability to respond to normative reasons.Footnote 9 Thus, to perform a full-fledged action, it’s not enough to perform that action intentionally—one must also form one’s intention in response to normative reasons.

However, even an intentional action performed in response to normative reasons can be compromised. To see this, we need to examine (a) what a normative reason is, (b) what’s involved in responding to a normative reason, and (c) the ways in which our limitations sometimes prevent us from responding to reasons. The fact that our limitations sometimes prevent us from responding to reasons entails that, sometimes, an agent must first undergo an intervening event in order to respond to a reason.

Roughly, a normative reason is a feature of one’s context that has a normative valence; it counts for or against performing some action.Footnote 10 Although I do not have a full account of the origin of normative reasons, it’s plausible that normative reasons are generated by the fact that some thingsFootnote 11 have genuine value; a feature of a context becomes a reason for an action in that context when performing the action would, in light of that feature, realize something of genuine value. We can distinguish the different types of normative reasons (moral reasons, reasons of rationality) by distinguishing between the different types of values that generate them (moral values, rational values).

To respond to a reason, one must (1) recognize that the feature that constitutes the reason obtains. For example, assume that, in some particular context, the fact that my cat is sick is a reason for me to give medicine to my cat. In order to respond to that reason, I must recognize that my cat is sick. (2) One must recognize that the reason-constituting feature has a valence, that is, that the reason-constituting feature is morally relevant; in order to respond to the reason that my cat is sick, I must recognize that the fact counts in favor of (or against) some action. (3) One must recognize the direction of the valence; in order for me to successfully respond to the reason that my cat is sick, I must recognize that my cat’s sickness favors medicine-giving (as opposed to some other action). (4) One must also be properly motivated by the reason. For example, in order to respond to the reason that my cat is sick, I must (all else being equal) be partially motivated to give my cat the medicine. And (5), to respond to a reason well, one must recognize the strength of the reason; in order for me to respond well to the reason that my cat is sick, I must see that the reason is strong enough to support actually giving my cat medicine (even if there are other reasons in my context that count against giving the medicine).Footnote 12 Thus, responding to a reason involves a cluster of mental states, including credences, beliefs, and desires. Given that agency is the capacity to respond to normative reasons, all agents must have some de re desires for things of genuine value,Footnote 13 as well as beliefs that allow them to act on those desires.

Every actual agent has different types of physical, psychological, and epistemic limitations—and these limitations determine the specific way in which one is disposed to respond to normative reasons.Footnote 14 (It’s these distinctive dispositions that explain the obvious datum that different agents respond to reasons and behave differently, even when placed in identical contexts.) Let’s call the specific way in which one is disposed to respond to normative reasons at a time the character of one’s agency at that time.Footnote 15 If one responds to normative reasons in a way that’s inconsistent with the most recent character of one’s agency, then one’s action is compromised.

For example, consider a case in which someone’s psychological dispositions and epistemic limitations affect the character of their agency, and as a result limit the range of full-fledged actions they can perform.Footnote 16 I’m a physician who has to administer a drug—either Drug A or Drug B—to my suffering patient. I care about not taking excessive risks with my patients, and I care about making medical decisions on the basis of good evidence.Footnote 17 I know that Drug A will help, but not cure, my patient; I know that there’s some chance that Drug B will cure my patient, but also some chance that Drug B will kill my patient. As a matter of fact, Drug B will cure my patient. Thus, there’s a normative reason in my context for me to administer Drug B (namely, the fact that Drug B will cure my patient). However, my epistemic limitations—combined with my concern for the patient and for practicing evidence-based medicine—prevent me from responding to that reason. Think about what it would take for me to prescribe Drug B (assuming that I cannot seek out further evidence): I could spontaneously form the belief that B is the cure, or I could spontaneously cease to care about protecting my patients from unnecessary risk, or I could spontaneously cease to care about the practice of evidence-based medicine. But all of these spontaneous changes are clearly intervening events, because they are changes in my beliefs or motivational states that are not themselves responses to reasons. The upshot of this example is that, to perform a full-fledged action, one must form an intention in response to normative reasons, and one’s response to normative reasons must be consistent with the recent character of one’s agency.

Thus, we arrive at a more detailed gloss of OIAC: if one morally ought to \(\phi\), then it is consistent with the way in which one is disposed to respond to normative reasons for one to form an intention to \(\phi\), and to form that intention in response to the normative reasons that support \(\phi\)-ing. More succinctly, we can say that if one ought to \(\phi\), then \(\phi\)-ing is consistent with the character of one’s agency.

It might be tempting to rest content with this version of OIAC. But this version remains underspecified, and as a result it runs the risk of sounding too permissive. After all, intuitively, I morally ought to make amends with my enemy, even if I’m not currently able to form a reason-responsive intention to do so (because I’m holding a grudge that prevents me from being able to respond to the reasons that support making amends). To address this worry, I suggest the following time-indexed version of OIAC:

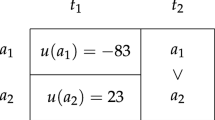

Time-Indexed OIAC: if S ought at t1 to \(\phi\) at t2, then either

- (a)

\(\textit{t1} = \textit{t2}\), in which case S agentially can \(\phi\) at t1, or

- (b)

t1 is distinct from (and earlier than) t2, in which case S agentially can at t1 perform some action \(\psi\), where \(\psi\) is an action (or a series of actions) that will make it agentially possible for S to \(\phi\) at t2.

The intuitive thought is that even if one cannot currently perform a full-fledged action that satisfies a demanding prescription, one still ought to perform full-fledged actions that will put oneself in a position to satisfy that demanding prescription later. Even if I can’t form an intention (by responding to normative reasons in a way consistent with the character of my agency) to make amends with my enemy today, I should still, say, go to therapy (assuming that I can do so by responding to reasons in a way that’s consistent with the character of my agency), which will in turn enable me to make amends later. Thus, even if an OIAC-respecting moral theory’s short-term prescriptions are not terribly demanding, its long-term prescriptions can be extremely demanding.Footnote 18

To summarize so far: Given OIAC, it’s never the case that one ought to perform an action that requires an intervening event—such an action is “compromised.” However, one is sometimes able to perform an uncompromised action that changes the way in which one is disposed to respond to reasons. In other words, one can change the character of one’s agency through the exercise of one’s agency. Such changes are not intervening events, because they are the result of the full-fledged exercise of agency; so, an adequate moral theory can prescribe such changes.

Thus, an action is agentially possible when one can perform it as a full-fledged action. Moreover, an action that is not agentially possible for one at t1 might nevertheless be agentially possible for one at t2, because there might be agentially possible steps one can take to change which actions are agentially possible for oneself. The concept of agential possibility captures the idea that there are certain actions that are genuinely “within one’s power” as an agent, that there are other actions that are not within one’s power as an agent, and that which actions are (and are not) within one’s power is partly a function of the way in which one is disposed to respond to normative reasons. I will make one further assumption about agential possibility: I assume that, typically, an agent has multiple agentially possible actions available to them. I make this assumption because I intend for the concept of agential possibility to be compatible with the way that we usually think about the exercise of agency; if most agents have only one agentially possible action at any given time, then the way we usually think about the exercise of agency is illusory. Although I haven’t argued for this assumption, it helps us more clearly understand this concept of what one can do “through the exercise of one’s agential powers.” Agential possibility is, I’ve argued, a notion of possibility that is particularly relevant to moral theorizing, because of the relationship between moral prescriptions and the exercise of agency—this further assumption allows us to capture the intuitive idea that agents often choose between multiple options, each of which is “possible” in the morally relevant sense.

Although I assume that an agent typically has more than one agentially possible action, I’ve also argued that one’s agentially possible actions are restricted (because of the character of one’s agency). In response to my claim that the character of a person’s agency restricts what’s agentially possible for that person, one might object that whenever there are normative reasons for an agent to perform an action, that agent is always “agentially able” to perform that action (without undergoing an intervening event), because that agent always has access to those reasons and also has the disposition to respond to them.Footnote 19 If this objection is correct, then a moral theory can respect OIAC while requiring that we perform extremely demanding actions immediately.

I am not convinced that it’s always possible for an agent to uncover all of the normative reasons in their context while retaining the character of their agency; our limitations are too great. However, the boot-strapping procedure I just described—in which one responds to one’s reasons (in the way one is presently disposed to respond to them) and thereby changes the character of one’s agency—is possible. And thus perhaps it’s always possible, in principle, for one to respond to all of the reasons in one’s context without having to first undergo an intervening event. But still, it’s clear that because of our physical and psychological limitations, such a boot-strapping procedure takes time. We cannot think at the speed of light; and even highly reason-responsive changes in our desires and thought-patterns must sometimes take place gradually. (For example, perhaps you can remember a time when you discovered that you had a good reason to forgive someone who wronged you. Still, the process of forgiving them might have taken a long time; sometimes to forgive people, we need time and space to process our thoughts and emotions. Similarly, it can take time to seek out new evidence to overcome epistemic limitations.) If this is correct, then a moral theory that’s consistent with OIAC can prescribe that normal non-ideal agents perform extremely demanding actions, but only in the somewhat distant future. Thus, even if we grant that for any agent in any context, there is some series of full-fledged actions by which that agent can come to discover the normative reasons that are operative in that context, it doesn’t follow that a moral theory can require that that agent immediately respond to those reasons; such a demand would amount to a requirement to undergo an intervening event.

1.2 A non-ideal moral theory: OIAC objectivism

OIAC provides the scaffolding for a compelling non-ideal moral theory. But in order to see this, it will be helpful to have one more assumption in place: that an adequate moral theory ranks actions on the basis of those actions’ relation to moral values, and then delivers deontic verdicts about those actions based on their place in the ranking. Let’s call this the ranking assumption. We might not need the ranking assumption in order to use OIAC to develop a non-ideal theory. Still, the ranking assumption gives us a simple way of seeing how OIAC can be used to generate a non-ideal moral theory.

Grant the ranking assumption: specifically, an adequate moral theory ranks the actions that are logically possible for an agent (in a context, at a time), and does so on the basis of those actions’ relation to moral values. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that the relevant relation is the promotion relation.Footnote 20 So, an adequate moral theory ranks an agent’s logically possible actions according to the extent to which each action promotes moral value. OIAC then “disqualifies” all agentially impossible actions in the ranking from being prescribed.Footnote 21 The theory then prescribes one of the remaining agentially possible actions based on its position in the ranking. Plausibly, the theory prescribes the highest-ranking agentially possible action.Footnote 22 A moral theory with this structure entails that one should perform better (i.e., more value-promoting) actions as one’s agential abilities increase, and that one is morally permitted to perform worse (less value-promoting) actions as one’s agential abilities decrease. For ease of exposition, I will call this schematic non-ideal theory OIAC Objectivism. OIAC Objectivism provides us with an account of the objective moral prescriptions delivered to imperfect moral agents.Footnote 23

One point of clarification: although we can say that one “ought to” or “should” perform the highest ranked agentially possible action, we should not say that one is obligated to perform the highest ranked agentially possible action. To see why one isn’t obligated to perform the highest ranked agentialy possible action, imagine a scenario in which there is objective reason for someone to make amends with their enemy, but they cannot do so in a way that is consistent with the present character of their agency (and thus they cannot do so soon, unless they first undergo an intervening event). However, they are very fortunate to have a spontaneous epiphany, and the character of their agency changes, albeit not in response to any reasons. As a result of their epiphany, they form an intention to make amends on the basis of the objective reason that they’re newly capable of responding to. It seems that, in this situation, they perform an action other than the highest ranked agentially possible action (and they do so as a result of undergoing an intervening event), and yet they do not violate an obligation. This suggests that the moral theory does not deliver the deontic verdict that the highest ranked agentially possible action is obligatory. The highest ranked agentially possible action is prescribed in the sense that it’s the only permissible agentially possible action in the ranking, and thus we can sensibly say that one “ought to” perform that action. There are other permissible actions in the ranking, but one can only perform those actions by first undergoing intervening events. Thus, according to OIAC Objectivism, there are no obligations other than obligations to refrain from performing actions that are lower in the ranking.

2 A non-ideal answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question

OIAC Objectivism is both schematic and controversial. However, in this section, I show that a theory with this structure provides a compelling answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question. The fact that it gives a compelling answer to the Question—and more generally offers a unified account of what imperfect moral agents morally ought to do—lends further credence to OIAC Objectivism.

2.1 Non-ideal prescriptions for morally uncertain agents

In Sect. 1.1, I argued that one’s psychological and epistemic limitations shape the specific way in which one is disposed to respond to normative reasons. That is, such limitations shape the character of one’s agency. And I argued that it’s never the case that one ought to perform a compromised action (although one sometimes ought to change the character of one’s agency, as long as one can do so through the exercise of one’s agency). I used a well-known example of empirical uncertainty—uncertainty about whether Drug B is a cure or a killer—to illustrate how the character of one’s agency can restrict what’s agentially possible.Footnote 24

Moral uncertainty, like empirical uncertainty, can decrease the range of value-promoting actions that are consistent with the character of one’s agency; as a result, moral uncertainty can constrain which actions OIAC Objectivism can prescribe. However, whether—and in what way—an agent’s moral uncertainty constrains what’s agentially possible depends on the details of the agent’s psychology.

First, notice that moral uncertainty does not always constrain what’s agentially possible. In some cases, an agent might be uncertain about which of several courses of action is morally right, and yet all of those courses of action remain agentially possible. Imagine that Lou has picked a small bouquet of flowers, and wants to deliver them to someone who is struggling with isolation. Lou can deliver the flowers to their nextdoor neighbor, or to their Aunt who lives across town. Lou genuinely doesn’t know which delivery would be best, but both are perfectly consistent with the character of Lou’s agency. In this type of case, OIAC Objectivism would say that Lou ought to perform whichever action best promotes moral values (and if they are equally value-promoting, then both are permitted). Of course, Lou does not know which action best promotes moral values; I’ll have more to say about the problem of action-guidance in Sect. 2.3.

But there are other cases in which an agent’s moral uncertainty—in combination with other features of the agent’s psychology—does constrain what’s agentially possible. Perhaps the clearest examples of this are cases in which an agent’s moral uncertainty makes particular courses of action morally risky;Footnote 25 if the agent is highly averse to taking moral risks and also has a less risky option available, then the risky courses of action can become agentially impossible for that agent. Here’s one such example:

Triage: Ayo is a physician who must decide how to distribute a scarce medical resource, Drug D. D is used to treat a dangerous illness, Condition C. Ayo has three patients suffering from C. Patients 1 and 2 are relatively healthy (other than having C), and so would need smaller doses of D in order to recover. Ayo has enough of D to cure Patients 1 and 2. Patient 3 has a pre-existing disability that makes higher doses of D necessary for recovery. If Ayo treats Patient 3 with D, then there won’t be enough D leftover for Patients 1 and 2. Ayo is uncertain: should they administer D to Patients 1 and 2, or should they administer D to Patient 3? On the one hand, it might be very bad to use up D on a single patient when it could instead help two patients; on the other hand, it might also be very bad to deny treatment to Patient 3 on the basis of their disability status. Assume that Ayo is extremely conscientious—they care about helping as many people as they can, and about not discriminating against patients on the basis of disability status. Ayo wants to avoid making this important decision recklessly. Now assume Ayo has three options: (a) administer D to Patients 1 and 2, (b) administer D to Patient 3, or (c) consult with and follow the guidance of the hospital’s clinical ethicist. This range of options, combined with Ayo’s conscientiousness and aversion to moral risk, makes options (a) and (b) agentially impossible. In order for Ayo to choose option (a) or (b), Ayo would have to undergo an intervening event in order to become less conscientious, or to become more risk-affine.Footnote 26

The upshot of Triage is that when an agent with a certain kind of psychology experiences moral uncertainty, their moral uncertainty constrains what’s agentially possible for them. Perhaps in Triage, the most value-promoting action is (b), or perhaps it’s (a); but either way, the non-ideal theory I’ve described would say that Ayo ought to perform (c), because (c) is the most value-promoting agentially possible action. Ayo’s moral uncertainty prevents them from responding to the normative reasons that favor other, more value-promoting actions.

One might object that, in Triage, I’ve merely stipulated the details of Ayo’s psychology in a way that makes (a) and (b) agentially impossible for Ayo. This is correct—I have stipulated the details of Ayo’s psychology—but this is not actually a problem, because I merely want to argue that there are some cases in which moral uncertainty constrains what’s agentially possible. I do not claim that moral uncertainty always constrains what’s agentially possible. If Ayo were risk-affine, or were not morally conscientious, then both (a) and (b) would, presumably, remain agentially possible. My point is that moral uncertainty can sometimes shape the character of a person’s agency, and thus can sometimes limit what one is agentially able to do. Perhaps the objector would ask why we should think that any real person in Ayo’s situation would be agentially incapable of doing either (a) or (b). In response, I can report that some real-life morally conscientious people certainly seem to be incapable of performing full-fledged actions they regard as extremely morally risky, especially when there exist much less risky options; I take it to be plausible that, for these people, selecting the very risky option would be inconsistent with the (risk-averse) character of their agency. The extent to which real-world moral uncertainty restricts what’s agentially possible for real-world people ultimately depends on the details of real-world people’s psychology; but I find it extremely plausible that moral uncertainty restricts the agential possibilities of some real-world people, at least sometimes.

OIAC Objectivism provides us with a schematic answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question: of those actions that a morally uncertain agent can perform as a result of forming a reason-responsive intention (in a way that’s consistent with the character of the agent’s agency), the agent morally ought to perform the action that best promotes moral values. It’s not necessarily the case that the morally uncertain agent ought to perform the action that is most strongly supported by normative reasons in the context, because the agent’s moral uncertainty might prevent them from responding to those reasons.

2.2 Transitional and non-transitional non-ideal prescriptions

So far, I’ve argued that one’s moral uncertainty places constraints on which actions OIAC Objectivism can prescribe. But moral uncertainty affects what we morally ought to do in another way: it generates non-ideal moral reasons. One way to understand what OIAC Objectivism demands of us—including what it demands of the morally uncertain—is to look at how it handles transitional and non-transitional moral reasons.Footnote 27 Moral uncertainty is a failure to respond to some of the moral reasons in one’s context, and such failures can themselves generate moral reasons for action.

No matter our axiological commitments, we should agree that when one encounters an obstacle to promoting moral values, one can then promote moral values by addressing that obstacle. Obstacles to the promotion of value generate non-ideal reasons to deal with those obstacles.Footnote 28 Because moral uncertainty is a type of obstacle to promoting moral values (because it’s an obstacle to responding well to moral reasons), it can generate new, non-ideal reasons. In other words, the fact that I’m morally uncertain can itself constitute a moral reason to behave in certain ways.

Sometimes, an obstacle creates a “transitional” reason, which is a reason to remove the obstacle. For example, imagine that you need to arrive at work on time, but you encounter an obstacle in the road. If the best way to make sure you still get to work on time is to move the obstacle, then the obstacle’s existence generates a transitional reason to move it. But other times, an obstacle creates a “non-transitional” reason, which is a reason to work around the obstacle. Imagine that you need to arrive at work on time, encounter an obstacle in the road, but can’t move the obstacle. In this case, the obstacle’s existence generates a non-transitional reason to work around it (by, say, taking an alternate route, even if that route is longer).

When we think of moral uncertainty as an obstacle to responding well to moral reasons, we can see that moral uncertainty can generate both transitional and non-transitional moral reasons. One’s moral uncertainty can generate a transitional reason to resolve one’s uncertainty; this will be the case when acting so as to resolve one’s uncertainty will promote the most moral value. But if one’s moral uncertainty isn’t resolvable, then moral uncertainty generates a non-transitional reason; this reason might support hedging,Footnote 29 or it might support relying on moral testimony (as in the Triage example from Sect. 2.1). Certainly hedging and relying on the moral testimony of others are both less than ideal. But sometimes it’s the best that one can do in light of one’s limitations.

So, OIAC Objectivism now gives us the following more specific answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question. A morally uncertain agent ought to perform whichever agentially possible action best promotes moral value. In some cases, this action will involve working to resolve one’s moral uncertainty; in other cases, this action will involve doing the best one can in spite of one’s uncertainty. Although one’s moral uncertainty prevents one from fully responding to some moral reasons, one’s moral uncertainty itself generates new (non-ideal) moral reasons that one is typically capable of responding to; and often, responding to those new, non-ideal moral reasons is the best one can do. As I discuss in Sect. 4, this answer to the Question is significantly different from (and less costly than) other answers currently on offer.

2.3 Two criteria for evaluating answers to the moral uncertainty question

One might object that my answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question is unsatisfying, because it’s insufficiently action-guiding. After all, it’s rarely clear to us which of our available actions (even our agentially possible actions) would best promote moral values. We are often uncertain about what’s morally valuable, and about which actions bear the promotion relation to moral values. My answer to the Question does not provide guidance to the morally uncertain agent, because the answer relies on moral facts about which the morally uncertain agent is uncertain.

I do not think that OIAC Objectivism’s failure to provide this type of guidance to the morally uncertain agent is a significant problem. There are two competing desiderata for an answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question. First, we might want our answer to provide helpful guidance to the morally uncertain decision-maker. Second, we might want the answer to accurately describe the prescription delivered by the correct moral theory to the morally uncertain decision-maker. These two desiderata are in tension with each other, for three reasons. First, perfectly accurate descriptions of what one ought to do are rarely helpful from the perspective of a psychologically limited agent. (For example, when someone is learning to play baseball, it’s best to give advice like “keep your eye on the ball,” rather than describing every way in which the new player should move in order to most effectively hit the ball.) Second, in order for a theory to offer helpful advice to an agent, that theory must itself be discoverable by that agent. But given the significant limitations we all face, a moral theory that’s discoverable by any agent wouldn’t be much of a moral theory at all. And third, an answer that satisfied the first desideratum would have a different type of content than an answer that satisfied the second. An answer that provides helpful advice or guidance usually contains new information that the agent doesn’t already possess. But an answer that describes how one morally ought to act must (I’ve argued) take into account the mental states of the agent, lest our moral theory prescribe compromised actions.

OIAC Objectivism satisfies the second desideratum—it accurately describes what a morally uncertain agent ought to do. It does not fully satisfy the first desideratum, because the morally uncertain agent will not be able to reliably discover that the prescribed course of action is, as a matter of fact, what they ought to do. However, OIAC Objectivism is still followable.Footnote 30 OIAC Objectivism’s prescriptions are “followable” in the sense that they refer only to full-fledged actions that are genuinely available to the agent; for any action prescribed to an agent by the theory, there is a path (consistent with the character of their agency) by which they can come to perform that action.

Moreover, OIAC Objectivism is helpful, even if not reliably action-guiding. First, it’s helpful because it directs our attention to the features of our context that are most salient for making decisions while morally uncertain. According to OIAC Objectivism, our moral uncertainty can itself generate non-ideal moral reasons, and thus we ought to turn our attention to our uncertainty, and deliberate about how to act in light of it. OIAC Objectivism also directs us to turn out attention toward axiological questions, because how a morally uncertain agent ought to act is determined by what’s morally valuable. Second, OIAC Objectivism is helpful insofar as it provides an answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question we can accept. According to this answer, a morally uncertain agent still has a number of genuine actions available to them, and they morally ought to perform whichever of those best promotes moral values. I can accept that I ought to do the best I can, given my very real limitations, whereas I cannot accept an answer according to which I ought to spontaneously become an omniscient saint.

3 Other answers to the moral uncertainty question

Every answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question has intuitive costs. However, the answer I’ve provided—which rests on a non-ideal theory I’ve called OIAC Objectivism—is one of the least costly.

Generally speaking, answers to the Moral Uncertainty Question fall into two categories: “objectivist” and “subjectivist.” Roughly, according to objectivist answers, what one morally ought to do is determined by “the facts,” and not by one’s mental states. According to subjectivist answers, some of one’s mental states play a role in determining what one morally ought to do. However, OIAC Objectivism (along with other non-ideal moral theories) challenges this way of drawing the distinction between objectivist and subjectivist answers. According to OIAC Objectivism, one’s mental states place constraints on what one ought to do, and can generate new moral reasons; thus, OIAC Objectivism is mental state sensitive. And yet, OIAC Objectivism is best understood as an objectivist theory. First of all, it’s a theory of what one genuinely morally ought to do; one’s non-ideal moral prescriptions are one’s genuine moral prescriptions, and they cannot be contrasted with more “objective” prescriptions. Second of all, the moral reasons generated by one’s mental states (such as moral uncertainty) are, on my view, objective reasons. The traditional way of drawing the distinction between objectivist and subjectivist theories obfuscates the ways in which an objectivist theory can be mental state sensitive.Footnote 31

But for the time being, let’s grant the distinction between objectivist and subjectivist answers. As we’ll see, standard versions of these views have serious intuitive costs and, more specifically, they often provide unacceptable answers to the Moral Uncertainty Question. Traditional objectivist and some subjectivist theories entail violations of OIAC, and as a result provide unacceptable answers to the Question. Other subjectivist theories respect OIAC, but only at the cost of being excessively permissive.

3.1 OIAC violations

Many alternatives to OIAC Objectivism entail violations of OIAC. If my argument in Sect. 1.1 is correct, then these alternative theories fail to prescribe full-fledged actions to real-life agents, and thus fail to satisfy an important desideratum for an adequate moral theory.

According to standard objectivist views about moral prescriptions, an agent’s beliefs and credences do not affect what that agent morally ought to do. Clearly, such views entail violations of OIAC. For example, on Peter Graham’s view, the physician who must choose between administering Drug A (the partial cure) and Drug B (the total cure, which the physician reasonably believes might kill the patient) ought to administer B.Footnote 32 But, as I argued in Sect. 1.1, given a possible specification of the character of the physician’s agency, the physician cannot administer Drug B without first undergoing an intervening event.Footnote 33

Some subjectivist views also entail violations of OIAC. For example, according to some subjectivists, one’s non-moral credences can affect what one morally ought to do, but one’s moral credences cannot affect what one morally ought to do.Footnote 34 These subjectivists agree that the physician who is uncertain about the safety of Drug B ought to administer Drug A, because one’s non-moral credences can affect one’s subjective moral obligations. But, these subjectivists hold that one’s uncertainty about moral matters has no effect on one’s subjective moral obligations. Such subjectivist views are compatible with the prescription of actions that require intervening events. For example, such subjectivist theories could prescribe that Ayo immediately give Drug D to Patients 1 and 2, in spite of the fact that the character of Ayo’s agency prevents Ayo from forming a reason-responsive intention to do so. As I’ve already argued, one’s moral credences sometimes constrain which full-fledged actions one can perform; a theory that ignores those constraints does not reliably prescribe full-fledged actions to actual moral agents.

Moreover, some alternative objectivist non-ideal moral theories entail violations of OIAC.Footnote 35 On Holly Lawford-Smith’s view, our moral obligations are constrained by a different ought-implies-can principle: if one ought to \(\phi\), then if one tries to \(\phi\) one will probably succeed in bringing about a good “non-ideally accessible” state of affairs. A state of affairs S is non-ideally accessible at a time for an agent just in case the objective epistemic probability of S conditional on the agent performing the action of theirs that’s most likely to bring about S is greater than some contextually defined threshold (where the threshold is set by how much is morally at stake).Footnote 36 Lawford-Smith acknowledges that a non-ideal theory should be sensitive to an agent’s epistemic position; this is why she holds that an agent’s beliefs about which actions are possible can constrain what the agent ought to do. However, Lawford-Smith also holds that, “ignorance about reasons for action is not grounds for saying that actions are not available to agents.”Footnote 37 As a result, Lawford-Smith’s view entails that one can be non-ideally obligated to rescue a child who’s drowning next door, even though one has no idea that that child exists.Footnote 38 After all, if one tried to rescue the child next door, one would probably succeed. But on my view, trying to rescue a child whose existence one is ignorant of would require an intervening event, and thus a moral theory cannot prescribe it.

According to Amy Berg’s non-ideal theory,Footnote 39 we are subject to multiple obligations at different levels of ideality. Our ideal obligations are governed by a “thin” voluntarist constraint, according to which one ought to \(\phi\) only if one physically can \(\phi\); these ideal obligations are important, according to Berg, because they “determine the ultimate standard for judging actions.”Footnote 40 However, Berg also holds that our non-ideal obligations are governed by a “thicker” voluntarist constraint, according to which one ought to \(\phi\) only if one motivationally and psychologically can \(\phi\). These non-ideal obligations, according to Berg, are important for action-guidance. This type of view entails that we routinely fail to satisfy some of our moral obligations, namely, our ideal moral obligations (which are constrained only by our physical abilities). Thus, Berg is committed to a moral theory that prescribes actions that one can perform only by first undergoing an intervening event. Berg would not be worried by this consequence, because one’s ideal obligations are not supposed to guide action; rather, they set an “ultimate standard” for evaluating actions. But I confess that I don’t see why we need an ultimate moral standard that’s set by practically unsatisfiable prescriptions; with OIAC Objectivism, we get “ultimate moral standards” from the axiological component of our moral theory.Footnote 41 Moreover, it’s difficult to conceive of these unsatisfiable ideal obligations as setting standards for action, given that one cannot perform full-fledged actions that satisfy them.

Chelsea Rosenthal develops a “two-level” theory, according to which there exist both procedural oughts and substantive oughts; procedural oughts express moral norms that direct us to act in ways that will help us satisfy other moral norms, whereas substantive moral norms are non-procedural.Footnote 42 On this picture, both types of oughts deliver genuine prescriptions for action—substantive oughts tell the agent what they ought to do, and procedural oughts tell the agent how they ought to go about attempting to satisfy the substantive oughts. For example, imagine that it’s permissible to eat meat, but that a person thinks there’s some chance that it’s impermissible to eat meat; nevertheless, they take a moral risk by eating meat. On Rosenthal’s view, we can say that the person in this case acts in a way that is substantively permissible, but procedurally impermissible (because it’s procedurally impermissible to take such a risk). My primary concern about Rosenthal’s position is that both types of norms—substantive and procedural—could, in principle, violate OIAC. Certainly the substantive norms will frequently violate OIAC. For example, if meat-eating is wrong is a substantive norm, but I’m entirely unaware of that norm, then (given some plausible assumptions about my psychology and environment) I won’t be able to comply with it unless I first undergo an intervening event. Moreover, Rosenthal’s procedural oughts can prescribe actions that agents cannot perform unless they first undergo an intervening event; this is because the procedural oughts are not necessarily constrained by what’s agentially possible.Footnote 43

3.2 Excessive permissibility

OIAC Objectivism avoids the problem of OIAC violations, because OIAC is part of the very foundation of the theory. Of course, there are other answers to the Moral Uncertainty Question that do not violate OIAC; however, most of these other answers presuppose moral theories that are extremely permissive. Although OIAC Objectivism is in some ways permissive, it is much less permissive than other OIAC-respecting moral theories.

There is a natural way of constructing a moral theory that respects OIAC: develop a subjectivist theory according to which what one morally ought to do is entirely determined by one’s mental states (including both moral and non-moral credences). For example, some versions of the view that one morally ought to “maximize expected moral value” respect OIAC. On this view, when one is uncertain between mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive moral propositions, one must determine the moral value of one’s prospective actions conditional on each of those propositions, and then weight those values according to one’s credence levels in the propositions. One should then perform whichever action has the highest weighted average moral value.Footnote 44 Similarly, Zimmerman’s “prospectivism” respects OIAC. According to Zimmerman, one’s moral obligations are determined by one’s justified credences, where one’s justified credences are the credences one has that are rational, given the evidence one has availed oneself of.Footnote 45

One problem with these sorts of views, however, is that they’re excessively permissive. The view that one ought to maximize expected moral value entails that one ought to behave horribly when one divides one’s credences between horrifying moral propositions. Prospectivism similarly entails that one ought to behave horribly when one has rational credences in horrifying moral propositions,Footnote 46 and that one ought to behave horribly even if there are better actions one agentially can perform. Imagine a moral agent who is “torn” about whether they should torture puppies or torture kittens. According to OIAC Objectivism, what this agent ought to do is a function of (a) which actions are agentially possible for the agent, as well as (b) which of those actions best promotes moral values; if the would-be animal torturer is agentially capable of doing something better than torturing an animal, then they should perform that better action. But according to these more extreme subjectivist and prospectivist views, the would-be animal-torturer ought to hurry up and start torturing.

OIAC Objectivism does not entirely avoid the problem of excessive permissiveness. After all, I have argued that what’s agentially possible for a person is determined by the character of that person’s agency, which is in turn shaped by that person’s limitations. As a result, there are possible cases—including possible versions of our animal-torturer—in which a very flawed person’s only agentially possible actions are horrifying. But let me offer an observation to assuage this worry.

Notice that even if there are many possible cases in which OIAC Objectivism prescribes horrible actions (because those actions are the best full-fledged actions that flawed agents can perform), we have reason to doubt that most actual agents have only horrifying agentially possible actions. The fact that OIAC Objectivism delivers counterintuitive results in unrealistic possible scenarios is not too worrisome, provided that it doesn’t deliver the same counterintuitive results about more realistic scenarios. The vast majority of actual agents have extremely messy psychological profiles. Sometimes this messiness constrains what’s agentially possible; but this messiness can also enable a person to have a relatively wide range of agentially possible options. For example, recall the would-be animal torturer. If that agent is at all like most of us—if the agent has a variety of concerns and motivations, some of which are unrelated to torturing animals—then that agent almost certainly has agentially possible options other than torturing puppies and kittens.Footnote 47 Perhaps it’s agentially possible for them to leave well enough alone and go take a nap.

At this point, one might object that OIAC Objectivism is indeed too permissive. Do we really want to say that all the would-be animal-torturer ought to do is go take a nap? I think this verdict about the animal-torturer is correct, assuming that taking a nap is the most value-promoting agentially possible action available to them. This is the cost of OIAC Objectivism: it cannot demand that an agent do better when doing better would require undergoing an intervening event. But keep in mind that OIAC Objectivism still has the resources to issue more demanding prescriptions of the would-be animal torturer later. As long as there is an agentially possible series of actions by which the agent can improve themselves, OIAC Objectivism will prescribe that course of action.

So, OIAC Objectivism is permissive in two ways. First of all, there are possible scenarios in which the theory prescribes horrifying actions; second of all, in many actual scenarios, the theory’s short-term prescriptions are not very demanding. In response to the first type of excessive permissiveness, I’ve suggested that those possible scenarios are rarely actual, because of the complexity of actual agent’s psychologies. In response to the second type of excessive permissiveness, I’ve admitted that OIAC Objectivism is permissive in that way; at the same time, I’ve drawn attention to the way in which it can still issue very demanding prescriptions later.

4 Moral ignorance

I have argued that views such as prospectivism and extreme forms of subjectivism respect OIAC, but suffer from the problem of excessive permissiveness; the problem is that these sorts of views simply direct agents to “act on” (some subset of) their moral credences. OIAC Objectivism is preferable to these views, because it does not simply direct an agent to act on their credences; according to OIAC Objectivism, if an agent is agentially able to act against their moral credences and thereby perform a better action, then that agent ought to perform that better action. (The would-be animal torturer should do something better than torturing an animal, assuming that doing so is agentially possible for them.) Although I admit that there are possible cases in which an agent has only horrifying agentially possible actions, I’ve argued that we have reason to think that such cases are rarely actual, because of the psychological complexity of most actual agents.

One might wonder: is it agentially possible for someone to act against their moral credences, and thereby do what they believe to be morally wrong? In response, it seems like agents often do act against their moral beliefs and credences, and do so in ways consistent with the character of their agency. (Think, for example, of those who routinely eat meat, while explicitly believing that it’s wrong for them to eat meat.) These real-life cases of people who routinely act against their moral credences make it extremely plausible that some of those with credences in horrifying moral propositions are agentially capable of acting in ways that they believe to be morally wrong. And on my view, an agent with horrible moral credences who is agentially capable of performing a better (more value-promoting) action that they believe to be morally wrong morally ought to perform that better action.

One might worry about the way in which I’ve responded to the charge of excessive permissiveness. I replied that even someone with horrifying moral credences can often act against those credences (while still retaining the character of their agency), and they should do so when doing so would best promote moral values. But if we can act against our moral credences, do our moral credences really constrain what we morally ought to do in the way I proposed in Sect. 2.1?

To answer this question, we must notice that the character of one’s agency is partly determined by one’s de dicto concern for morality.Footnote 48 Someone who isn’t bothered by immorality as such will be able to more easily act against their moral beliefs and credences while retaining the character of their agency; someone who cares deeply about doing the right thing as such will have a much harder time acting against their moral beliefs while retaining the character of their agency. For example, imagine someone who is uncertain about the moral status of animals, and thus is uncertain about what they ought to cook for dinner; and imagine that, as a matter of fact, all that matters morally is human wellbeing.Footnote 49 Further, assume that, as a matter of empirical fact, cooking a dinner filled with veal and foie gras would best promote human wellbeing (because that’s what would make this person’s dinner guests happiest). If the person we’re imagining has a great deal of concern for doing the right thing, then they will struggle to cook the meal of veal and foie gras while retaining the character of their agency—doing so would feel like taking a serious risk (much like giving Drug B to the patient would feel like a serious risk). But if the person we’re imagining doesn’t have a strong de dicto concern for morality, then it will be much easier for them to ignore their moral concerns about the wellbeing of animals and cook the meal that (in our imagined scenario) is best supported by moral reasons.

My response to the charge of excessive permissiveness pointed out that the agent with horrifying moral credences might still be able to act against those credences while retaining the character of their agency; if that’s agentially possible for them, then that’s what they should do. We now see that whether it’s agentially possible for someone to act against their moral credences will depend, in part, on their de dicto concern for morality. Thus, OIAC Objectivism can prescribe that a morally uncertain agent act in ways that the agent believes to be wrong (or risky), but only when the agent is agentially capable of performing those actions, which requires that they have relatively little de dicto concern for doing the right thing.

But now one might wonder: What if someone has horrifying moral beliefs, but cares deeply about doing the right thing as such? Perhaps the most challenging case for OIAC Objectivism to handle is fanatical moral ignorance. A fanatical morally ignorant agent fully believes a horrifying moral proposition, while at the same time being highly motivated by a de dicto concern for morality. This type of case is challenging for two reasons. First, even if we assume that moral ignorance—like moral uncertainty—generates non-ideal moral reasons, the morally ignorant agent cannot respond to those reasons. A morally uncertain agent can usually recognize their uncertainty, and thus can in principle respond to the non-ideal moral reasons generated by their uncertainty. But a morally ignorant agent does not recognize their own ignorance, and thus cannot respond to the non-ideal reasons generated by their ignorance. And second, if a morally ignorant agent is also highly morally motivated—in the sense that they care about doing the right thing de dicto—then it’s less plausible that they agentially can act in ways that they judge to be morally wrong. Given these two challenging features of cases of fanatical moral ignorance, doesn’t my theory entail that such a person ought to do terrible things?

In response to this concern, I first want to point out that the type of agent we’re imagining might not be a moral agent at all. We’re imagining a case in which someone fully believes horrifying moral propositions while at the same time having a deep concern for “doing the right thing.” It’s perfectly compatible with high quality moral agency to have de dicto concern for doing the morally right thing.Footnote 50 However, I do not think that one can be a full-fledged moral agent while only having de dicto concern for doing the right thing; in order to be a moral agent, one must have the capacity to perform actions in response to moral reasons, and responsiveness to moral reasons requires de re concern for things of moral value.Footnote 51 The person who has horrifying moral beliefs and mere de dicto concern for doing the right thing is not a moral agent. Presumably, moral theories do not prescribe actions to people who aren’t moral agents.

But let’s imagine that this person—with horrifying moral beliefs, and a deep de dicto concern for doing the right thing—also has some de re concerns for things of genuine moral value; in other words, let’s imagine that this person does, in fact, have the de re moral desires required for moral agency. For example, we can imagine that this person cares deeply about the wellbeing of their own children. But now notice that this person’s de re concern for things of genuine moral value plausibly enables them to perform value-promoting actions; rather than acting on their horrifying moral beliefs, it’s agentially possible for them to go take care of their kids. The more de re moral concerns the agent has, the more value-promoting actions become agentially possible for them.

Thus, when it comes to cases of fanatical moral ignorance, I will classify them into two types. One type of case involves agents who aren’t really moral agents at all, because they have no de re concerns for things of genuine moral value, and thus lack a capacity to respond to any moral reasons. When someone isn’t a moral agent, they receive no moral prescriptions. But the other, more common type of case involves agents who do, in spite of their horrifying moral beliefs, have some de re concerns for things of genuine moral value. My point is that such de re concerns will, at least often, make it agentially possible for such agents to refrain from acting on their horrifying moral beliefs, and to perform some better action instead.

Now one might object: the fanatical, morally ignorant agent is not necessarily agentially capable of going to care for their children (instead of acting on their horrifying moral beliefs), because their de dicto concern for doing the right thing could be much stronger than their concern for their children. (Or perhaps they’re not worried about their children at the moment, because the children are already cared for by someone else.) Doesn’t OIAC Objectivism entail that some fanatical morally ignorant agents morally ought to do horrible things?

Perhaps, but I think that OIAC Objectivism will only rarely, if ever, prescribe horrible actions to such agents. At this point, we can appeal to the imagined person’s status as a rational agent. Maybe this person doesn’t have enough de re moral concerns to make it agentially possible for them to perform a better action. But we are assuming, I take it, that they are a rational agent, and thus are to some extent capable of responding to reasons of rationality. I think it’s plausible that there oftenFootnote 52 exist reasons of rationality for one to exercise humility, and to carefully examine one’s beliefs (particularly when those beliefs have serious practical implications). The fanatical morally ignorant agent will have a reason—that they’re probably capable of responding to, because they’re a rational agent—to carefully examine their beliefs. Thus, if the person we’re imagining is a rational agent, then they have an action available to them that isn’t horrifying, namely, the careful scrutiny of their beliefs. OIAC Objectivism will prescribe that they perform that action, unless there’s an even better value-promoting action that’s agentially possible for them. Of course, we can describe a possible fanatical, morally ignorant agent whose only agentially possible actions are terrible; we can imagine someone whose de re concerns are insufficient to generate better agentially possible options. My suggestion is that most actual agents are not like this; at the very least, most actual agents seem to be capable of taking very small steps to improve themselves, in a way that’s consistent with the character of their agency.

Perhaps it will turn out that, sometimes, the best thing for a morally ignorant person to do is act on their false moral belief (or to behave irrationally, or to behave in a way they think is immoral, or to do something else entirely). Exactly which sorts of transitional and non-transitional prescriptions are generated by moral ignorance is a difficult matter, which will ultimately have to be resolved by the axiological theory we pair with OIAC Objectivism. The non-ideal prescriptions OIAC Objectivism delivers to the fanatically morally ignorant will turn out to be much worse than the prescriptions it gives to better agents. But this is exactly what we should expect from a non-ideal theory.

5 Conclusion

I’ve argued that a morally uncertain agent ought to perform whichever agentially possible action best promotes moral values (regardless of whether the agent is aware that this is what they ought to do). To require anything more of a morally uncertain agent would amount to a requirement that they undergo an intervening event, which would violate an important desideratum for a moral theory. And to require less of a morally uncertain agent would be excessively permissive. Moral uncertainty—along with other sorts of agential limitations—places constraints on what one morally ought to do by placing constraints on which full-fledged actions one can perform. In addition, moral uncertainty generates non-ideal moral reasons; our moral uncertainty can itself provide us with reasons to behave in certain ways (even if those behaviors are worse than the ways in which someone with moral knowledge ought to behave).

I’ve left many issues unaddressed. Although I’ve provided a sketch of the conditions under which an action counts as “agentially possible,” I haven’t provided a full account of agential possibility. Moreover, the position developed in this paper rests on a number of axiological assumptions that I haven’t defended. Nevertheless, I think that OIAC Objectivism provides a compelling account of the moral prescriptions of the morally uncertain, and has the resources to provide a compelling account of the moral prescriptions of other types of imperfect agents.

Notes

We can’t answer this question by appealing to claims about rational norms, because it’s conceivable that rational norms diverge from moral norms.

Note that I’m focusing on “pure” or “morally-based” moral uncertainty, that is, on moral uncertainty that isn’t traceable to non-moral uncertainty. Although the focus of this paper is on pure moral uncertainty, we can extend the view developed in this paper to instances of impure moral uncertainty, as well as to other types of uncertainty and ignorance.

In other words, a moral theory is “non-ideal” when its action-prescriptions are sensitive to the flaws—including moral flaws—of agents. Many non-ideal moral theories focus on the ways in which oppression morally compromises agents who are members of oppressed groups; the non-ideal theory I favor is also sensitive to agential imperfections that aren’t immediately traceable to the experience of oppression. See Mills (2005), Rivera-López (2013), and Tessman (2010).

Not all deontic verdicts express prescriptions; for example, when a moral theory delivers the deontic verdict that \(\phi\)-ing is forbidden, we shouldn’t say that the theory “prescribes” \(\phi\)-ing. A paradigm case of a moral theory prescribing an action is a moral theory that delivers the deontic verdict that \(\phi\)-ing is obligatory. A moral theory can also be said to prescribe \(\phi\)-ing when it delivers the deontic verdict that \(\phi\)-ing is permissible, and no other action in the context is obligatory or permissible. As I will clarify in Sect. 1.2, on my view, it is possible for an agent to have only one permissible action available to them, and yet at the same time not be obligated to perform that action.

For example, philosophers disagree about whether “supererogatory” is a genuine deontic status. For an excellent overview of the main debates about supererogation, see Muñoz (forthcoming).

Portmore makes a similar observation when he writes, “Now, it would be very strange to think that morality could require me to respond inappropriately to my reasons given that what makes me the sort of subject to whom moral obligations and responsibilities apply is that I’m the sort of subject who’s capable of responding appropriately to my reasons—that is, a rational agent. And it seems nonsensical for some moral requirement to apply to me because I have the capacity to respond appropriately to my reasons if I can fulfill that requirement only by failing to respond appropriately to my reasons.” See Portmore (2019, pp. 177-178).

If a third party is deliberating about what someone else ought to do, it’s pointless for the third party to consider agency-compromising events that one could undergo. The consideration of agency-compromising events wouldn’t help the third party see what one ought to do, because an agency-compromising event is something that an agent can’t produce through a full-fledged exercise of their agency.

Notice that agential possibility is distinct from other types of possibility. First, it’s distinct from physical possibility. There are some physically possible actions that are not agentially possible, because they rely on intervening events. There could also be physically impossible actions that are agentially possible; this could happen if there are physically impossible worlds in which the agent continues to respond to reasons in a way that is characteristic for the agent. (Thus, even if physical determinism is true, an agent could still have multiple agentially possible courses of action.) Second, agential possibility is distinct from psychological possibility (although I suspect that the two are related). For example, an action could be psychologically possible for me, and yet might require that I not respond to normative reasons at all; that action would be psychologically possible but agentially impossible.

I contrast normative reasons with motivating reasons. I treat normative reasons as a broad category; they include both moral reasons and reasons of rationality.

Note that a normative reason need not be a decisive reason; it can be “outweighed” by other reasons. Although I sometimes use the language of “weighing” reasons, I don’t intend for the reader to take the weight metaphor too seriously.

“Things” here can include objects, states of affairs, actions, or persons; I want to remain neutral on what, exactly, the bearers of value are.

Thus, it’s plausible that in order to perfectly successfully respond to a reason, one must also respond well to other reasons in one’s context; responding well to all reasons in a context is the only way to properly judge any particular reason’s relative strength.

An agent has a “de re” (vs. “de dicto”) desire for x when it’s true of x that the agent desires it, even if the agent does not desire it under the description “x.” (If an agent desires x under the description “x,” then the agent desires x “de dicto”.) An agent who has the capacity to respond to normative reasons must have some de re desires for things of genuine value, because a person who lacks de re desires for anything of genuine value does not have the ability to be motivated by any normative reasons, and thus lacks the capacity to respond to normative reasons. One might still have the capacity to develop de re desires for things of genuine value, in which case we can say that the person has the potential for agency.

There might be features other than an agent’s limitations (such as personality quirks) that determine the way in which the agent is disposed to respond to normative reasons; even so, an agent’s limitations play a significant role in determining the character of one’s agency.

The “character of one’s agency” must be distinguished from one’s “character,” in the virtue-theoretic sense. We can speak of the character of one’s agency—the specific way in which one is disposed to respond to normative reasons—at a particular time, whereas one’s character (in the virtue-theoretic sense) is determined by one’s long-standing dispositions.

This is a variation of a case made famous in Jackson (1991).

I have added some new details about the physician’s psychological dispositions. This is because, according to the view I’m arguing for, whether an action is “agentially possible” for an agent depends on the specific details of that agent’s psychology—details that are not normally mentioned in standard presentations of this example.

At this point, the reader might wonder whether I’m endorsing Williams’ reasons-internalism, according to which (roughly) S has a reason to \(\phi\) if and only if (1) S has a subjective motivational set some element of which motivates S to \(\phi\) or (2) there is a sound deliberative route by which S could come to have such a subjective motivational set (Williams 1981). However, my view is not the same as Williams’. First, note that Williams’ view concerns practical reasons in general, whereas I focus on moral prescriptions in particular. Second, note that Williams’ view is a view about reasons and not about prescriptions or oughts. Third, my rough account of the origin of normative reasons is arguably in tension with reasons-internalism.

The objector might think that such a disposition is constitutive of agency.

It need not be the promotion relation; but the promotion relation gives us a simple way of seeing how such a ranking can be generated. Note that the ranking assumption, combined with the assumption that the relevant relation between actions and moral values is the promotion relation, amounts to the assumption that an adequate moral theory has a teleological structure. See Dietrich and List (2017).

Although agentially impossible actions might be able to receive other sorts of deontic verdicts. For example, even if it’s agentially impossible for me to kill my beloved cat, perhaps an adequate moral theory can still deliver the deontic verdict that killing my cat is wrong (or that killing my cat would be wrong). All I claim here is that agentially impossible actions cannot be prescribed—they cannot be what one morally ought to do.

If some agentially possible actions are physically impossible, we will need to introduce additional ought-implies-can principles—such as ought implies physically can—that place further contraints on which actions the theory can prescribe. The introduction of additional ought-implies-can principles is consistent with the thesis of this paper.

See Sect. 3 for a more detailed explanation of why I treat this non-ideal theory as an “objectivist” theory.

My account can be extended to other, more complicated forms of empirical uncertainty, such as miners puzzles (Regan 1980). What one morally ought to do, if one is in a miners puzzle, is the most value-promoting agentially possible action. Which action that is depends on (a) what the correct axiological theory says about how much moral value is promoted by each item on one’s menu of options and (b) the character of one’s agency.

Of course, if Ayo only has two options—(a) and (b)—then both options could be agentially possible for Ayo; this is because which options are agentially possible for an agent depends on the entire menu of options from which an agent chooses. For example, if I’m choosing between eating a cookie and sawing off my foot, sawing off my foot will be agentially impossible for me; but if I’m choosing between dying while trapped under a boulder and sawing off my foot, sawing off my foot could become agentially possible for me. Similarly, if Ayo has no one to turn to for consultation (and so (c) is no longer on Ayo’s menu of options), Ayo might be agentially able to choose (a) or (b).

I borrow the terms “transitional” and “non-transitional” from Berg (2018).

Hicks (2019).

The fact that my answer satisfies the second desideratum, while “half-satisfying” the first, allows me to avoid most of the critiques of non-ideal moral theory in Tessman (2010).

I develop this point in detail in Hicks (forthcoming).

Graham (2010).

Similarly, such objectivist views will also violate OIAC is cases of moral uncertainty. For example, Graham’s view entails that it’s not the case that Ayo, in the Triage example from Sect. 2.1, should pursue option (c).

Note that proponents of these non-ideal moral theories take their theories to be objective and mental state-sensitive, like my own.

Lawford-Smith (2013, pp. 655–658).

Lawford-Smith (2013, 662).

Lawford-Smith (2013, p. 662). Lawford-Smith says that even when an agent “has no reason” to act in a particular way, that action is still within the agent’s option set.

Berg (2018).

Berg (2018, p. 19).

Muñoz and Spencer make a similar point in section 4 of “Knowledge of Objective ‘Oughts’: Monotonicity and the New Miners Puzzle” (forthcoming).

Rosenthal (2019, p. 10).

See Rosenthal (2019, p. 14), for a discussion of how procedural oughts can be determined by more objective or more subjective factors.

Zimmerman (2014).