Abstract

Yablo’s Aboutness introduces powerful new set of tools for analyzing meaning. I compare his account of subject matter to the related ideas employed in the semantics literature on questions and focus. I then discuss two applications of subject matter: to presupposition triggering and to ascriptions of shared content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 What is it about?

For a typical book in philosophy, a skim of the table of contents and, perhaps, a glance at the introduction suffices to provide an adequate idea of its main theses and arguments. (In extreme cases knowing the author’s name is sufficient.) Going ahead and reading the book is bit like attending a new production of a play one already knows: it can be valuable experience but not because anything unexpected happens. By contrast, even an entire read through Aboutness is likely to leave even the studious reader wondering what exactly has happened. This is not a criticism but rather a testament to the fact that the book is brimming with original ideas and problems. Many things happen in this book and not usually what you might expect. Stock characters of philosophy, such as nominalism and epistemic closure do appear, but many of the protagonists such as subject matters and logical subtraction are fresh faces.

My preferred way of viewing Yablo’s project is as an advertisement for a new way of thinking about meaning. It is a proposal to add substantial resources to the theoretical toolkit used by those thinking about semantics and pragmatics. These additions include finer and differently grained representations of sentential meaning as well as strategies for exploiting these new representations. Others may take the book more as an extended defence of a kind of nominalism (or at least agnoticism) about numbers and other metaphysically weighty positions. They can have their own Aboutness, I like mine better.

It is worthwhile recalling the contents of the usual toolkit—what the post-Quinean semanticist/philosopher of language brings to the table—in order to see why Yablo’s additions are truly novel. Sentences express meanings. Meanings are propositions. Propositions are some kind of object like a set of possible worlds or structured entities of the more Russellian sort. Entailment is the primary semantic relation. In standard theories, then, when we want to explain what a sentence can do for us, we talk about the proposition it expresses and what that entails. In extreme cases we also make reference to conventional implicatures or the like to cover aspects of meaning not strictly included in propositional content.Footnote 1

Yablo proposes that we should not just take sentences to express propositions but also to understand them as having subject matters. The subject matter of a sentence may be determined by the proposition it expresses, but not in any way that the standard framework can capture. Yablo argues that subject matters can help us make progress on some notoriously tricky topics such as, partial truth, relevant entailment, and explanation. While subject matters cannot be constructed out of the standard notions, Yablo does not take them as primitive but rather constructs them out of the ways in which sentences can be true or false, truthmakers and falsemakers. Talk of subject matters can be reduced to talk about truthmakers, but talk about truthmakers does not reduce to talk about standard propositions (or to talk about subject matters): so truthmakers are the main new primitive employed by Yablo.

Let’s start with what they are, these truthmakers and falsemakers. The first thing to note is despite the name they have little to do with standard use of the term ‘truthmaker’ in metaphysics. Yablo’s truth and falsemakers are closer in spirit to the atoms of Wittgenstein’s logical atomism than to anything in the literature on the metaphysics of truthmaking. In particular, truthmakers—in Yablo’s ontology—are just propositions themselves.

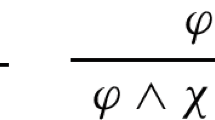

The simplest model of the view, explored in Yablo’s online appendix, is the one from propositional logic.Footnote 2 On this model we think of conjunctions of literals (atomic statements and their negations) as the potential truth and falsemakers of sentences. As an example the sentence \(A \vee B\) has as truthmakers A or B and, as its sole falsemaker, the conjunction \(\lnot A \& \lnot B\). So, for example, the sentence ‘either this dessert is unhealthy or this dessert is tasteless’ can have as a truthmaker the proposition that the dessert is unhealthy or the proposition that the desert is tasteless. However, the disjunctive proposition the sentence expresses is not its own truthmaker: it’s too disjunctive for that.

Note that sentences can ‘have’ truthmakers in very different senses. As I said \(A \vee B\) has as truthmakers A and B. However, its truthmakers in a given world depends on which of these propositions are true in that world. So, in any one world it can have either one, two or no truthmakers. In a world in which it is neither true nor false the sentence has as its falsemaker the conjunction of \(\lnot A\) and \(\lnot B\). Truthmakers are always conjunctive in form rather than disjunctive. So \(A \& B\) has a single conjunctive truthmaker (itself) while two possible falsemakers \(\lnot A\) and \(\lnot B\).

What is crucial to note is that on this toy model what truth and falsemakers there are depends on what the atomic formula are in the language. The atomic formula determine which complex sentences are sufficiently conjunctive in form to serve as truth or falsemakers. In languages with atomic propositions like ‘the table is grue’ there will be truthmakers that don’t exist in (more natural) languages where such a sentence can only be expressed disjunctively.

Truthmakers, thus, imports a notion of naturalness into semantics not found in the standard possible worlds framework. If you take possible worlds as the main semantic primitive and take semantics to be a mapping from sentences to possible worlds, you thereby lose any distinction between underlying disjunctive or conjunctive forms. The set of worlds where this chair is grue doesn’t look (formally) much different from the set of worlds in which it is blue: they are both just sets. However their disjunctive normal form in a sufficiently natural language (one without ‘grue’) does look different: one is more disjunctive than the other.Footnote 3

It is not actually fair to think of Yablo’s proposed addition to our toolbox as taking the form of a privileged language with its atomic primitives. First, he specifically eschews this way of speaking, treating truthmakers as propositions and not identifying them with parts of the language. (So even if we add ‘grue’ to our language after taking too many philosophy classes, we do not thereby call into being a gruesome truthmaker.) Second, while in propositional logic it is natural to treat truthmakers as conjunctions of literals, it is not entirely clear how this extends to natural language.

How do truthmakers and falsemakers relate to the titular notion of aboutness or subject-matter? Following Lewis (1988), we can think of subject-matter as a relation across possible worlds.Footnote 4 Two worlds are related to each other if they are the same with respect to their subject matter. Suppose a sentence is associated with its set of truthmakers. Its subject matter relation can now be defined by reference to these truthmakers. We can do this, for instance, by saying that for a sentence S, its subject matter is the relation m such that the \(w m w'\) if and only if there is a truthmaker of S that is true in both w and \(w'\).

2 Subject matters in linguistics

For those conversant with recent work in linguistics on semantics and pragmatics, Yablo’s notion of subject matter will seem both strange and familiar. It is familiar in that the notion of a subject matter or topic is one frequently appealed to in linguistic semantics. While David Lewis’s paper on subject-matter has not been greatly influential in philosophy of language, there is a prominent tradition of work on the semantics and pragmatics of questions and focus that employs very similar sounding and looking notions (e.g., Hamblin 1958, 1973; Karttunen 1977; Groenendijk and Stokhof 1984; Rooth 1985). In this literature the semantic value of certain sentences, questions, are identified with objects similar in form to Lewis’s or Yablo’s subject matters. So the question ‘Who came to the park?’ is associated (by some theorists) with an equivalence relation that relates worlds only where exactly the same people came to the park. Such equivalence relations can also be taken to be a topic or subject matter of a discourse in this tradition, which I’ll call the L(inguistic) S(semantic) notion of subject matter.

A striking difference, however, between Yablo’s notion of subject matter and LS conception is that they pertain to different objects. An LS subject matter is the semantic value of an interrogative sentence. It can also apply to discourses generally which are taken to have subject matters either explicitly or implicitly set by the questions they are addressed towards (e.g. Roberts 1996).

For Yablo, on the other hand, any declarative sentence possesses its own subject matter, and not the same one as that of the simple question of whether it is true or false (what I’d call the trivial subject matter of a sentence). No linguistic accounts of subject matter define the subject matter of a sentences in a non-trivial way, nor do semantic theories generally provide the theoretical resources to do so (i.e. by defining something akin to truthmakers and falsemakers). Rather the typical picture is that the subject matter of a sentence is given by the context and the sentence is interpreted in light of this given subject matter.Footnote 5

The existence of two notions of subject matter, the LS one and Yablo’s poses a bit of a problem. It is relatively easy to see why we have the LS notion. It plays an important role in explaining the semantics of embedded questions, the interpretation of question answers, and the way focal stress is used, among other things. But why do we also need Yablo’s notion? And what relation does his notion play to the LS notion?

In the rest of this note I will mostly be concerned with discussing the independent need for the kind of apparatus Yablo gives. I will start doing this by giving a potential application of truthmakers and falsemakers that is not to be found in his book.

3 An application: presupposition triggers

I hope now you have at least a vague notion of the main new tool Yablo is putting forward in his book. Sentences, according to Yablo, can be true (or false) in different ways. Ways of being true or false correspond to truthmakers, which are themselves propositions, and the set of ways of being true or false determine (somehow) the subject matter. Since this is a much richer object than we typically use in semantic analysis we need to see what work it can do to earn its keep.

In this section, I will try to show how this way of thinking may help us understand what presupposition are. Factive verbs like ‘know’ or ‘realize’ show presuppositional behaviour. A person saying either ‘He knows Lucinda is tall’ or ‘He doesn’t know Lucinda is tall’ or asking ‘Does he know Lucinda is tall’ would generally take for granted that Lucinda is tall. This is one of the indications that a sentence of the form ‘x knows that p’ presupposes p. It is an interesting question why such presuppositional expressions exist at all. In particular why should an assertion of a sentence and of its negation both seem to take for granted the same proposition? Almost everyone accepts that ‘x knows that p’ entails p, so the more pressing half of this question is why an assertion of its negation tends to indicate that the speaker believes p.

One explanation, of course, is that ‘x knows that p’ semantically presupposes p, that is, it is neither true nor false if p is false. Intuitively this seems wrong: after all, if JFK wasn’t shot by Oswald, than it’s simply false that Warren knew that Oswald shot Kennedy. This isn’t a knockdown argument: after all, trivalence is a theoretical posit and one needs to specify how exactly our judgments about truth and falsity connect to it. In any case, all else equal, it would be desirable to explain the behaviour of factive verbs such as ‘know’ without positing a trivalent semantics for it.Footnote 6

In the literature on presuppositions there is a recurring form of strategy for explaining why presuppositions exist in a bivalent framework (Stalnaker 1974; Wilson 1975; Grice 1981; Schlenker 2006). I’ll sketch one crude version of this: The first step is to say that ‘John knows that p’ requires at least two different things to obtain in order to be true: one that p is true the other that John bear an appropriate epistemic relation to p. We then try to explain the presuppositional behaviour of ‘John knows that p’ on the basis of it having this divisible content.Footnote 7 The next step is to observe that in denying that ‘x knows that p’ you could be doing one of (at least) two things: (a) denying that p is true at all, or (b) admitting that p is true but denying that x bears the right epistemic relationship to p. The third step, is to claim that it is a violation of some pragmatic principle to leave it ambiguous whether you are doing (a) or (b). (Usually this is something like the maxim of manner: if you wanted to leave it open which of these things you were doing, you should have used a form that more clearly articulated these two possible interpretations.) The last step is to claim that since (a) could have been expressed more simply (by denying p), the only clear interpretation is (b).Footnote 8

This is only the barest sketch of an account of why factive verbs give rise to presuppositions, and one that is open to numerous objections. I bring it up only to note that it crucially relies upon a notion of the different possible ways in a sentence can be true. On this story, the sentence ‘x doesn’t know that p’ can be made true by either p’s falsity or by x not bearing the right epistemic relationship to p. However, such factoring of a sentence into its different component parts is not something that our standard semantic provides for. For truth-conditions alone do not provide a unique disjunction of conditions which make the sentence true: in the possible worlds framework the set of worlds in which a sentence is false can be divided into as many different partitions as you like.Footnote 9 One needs to have a robust notion of the ‘natural’ ways in which a sentence can be true or false in order to tell a story like this. The apparatus of truth and falsemakers provide such natural divisions for us. LS subject matters do not make such distinctions, so Yablo’s apparatus does some very different work from them.

In particular, something like truthmakers would seem to be useful in solving what is called the triggering problem in the literature on presupposition (see, e.g., Abusch 2010; Abrusan 2011). This is the problem of explaining which terms give rise to presuppositions across languages. If this is not a brute fact, it must be explained in terms of the kinds of meanings they are trying to convey. A natural thought—one guiding the reasoning above—is that expressions that try to convey conjunctive meanings naturally presuppose one of their conjuncts. ‘x knows that p’ presupposes that p, ‘x stopped smoking’, presupposes that x used to smoke. The idea of conjunctive meanings, however, is trivial without a canonical way of diving meanings up: any sentence can be formulated as the conjunction of two other sentences. The resource of truthmakers, however, provide canonical ways of dividing meanings which can be leveraged to formulate a non-trivial notion of conjunctive meaning. Thus, they provide the kind of resource, which, in principle, could solve the triggering problem.

I say, in principle, because I do not know how to provide a solution to the triggering problem using truthmakers. I can only point in the direction the kind account I gave above suggests. If a sentence is conjunctive if it can be false in different ways—different of its conjuncts can fail. So ‘Bill and Ted travelled’ can be false because Bill didn’t travel or it can be false because Ted didn’t travel. Presuppositional expressions are those that have ‘hidden’ conjunctive meanings: conjunctive meanings that are not explicitly marked by conjunction or other grammatical devices.Footnote 10 A natural hypothesis is that any expression with a hidden conjunctive meaning will lead to presuppositions.The most developed view in this vicinity is Schlenker’s (2006). He postulates that conjunctive meanings pragmatically need to be ‘articulated’ explicitly unless one of the conjuncts is already being taken for granted. From this guiding thought he gives a detailed bivalent theory of the behaviour of presuppositions in natural language. If anything like his account is going to work, we need a kind of way of dividing up content such as Yablo’s notion of subject matter.

It is worth noting that in this area there are other notions in linguistics that have been used to fill the same gap. For example, some writers such as Abusch (2010) and Chemla (2008) posit sets of ‘alternatives’ associated with verbs such as ‘know’ in order to explain their presuppositions. My point is not that Yablo’s ways of being true (truthmakers) are the only way of building into one’s theories the kind of structure necessary to explain presupposition. It is just that it is an attractive way of making the kind of distinctions that many theorists are independently stipulating in their accounts.

4 Partial content

So far I’ve argued for two things: one, Yablo’s notion of aboutness is distinct from the similar notions we find in the semantics literature, and, two, his basic primitive of truth and falsemakers could play an important role in theorizing about meaning, particularly in the case of presuppositions. I want to move on to one of Yablo’s central applications of the notion of subject-matter and the apparatus of truth and falsemakers: the case of partial truth.

Earlier I talked of some content being naturally conjunctive, and thus consisting of distinct conjuncts. Another way of speaking—Yablo’s preferred way—is in terms of partial content. When does a proposition have another one as its part? In a classical framework there is is no non-trivial notion in this vicinity: all entailments of a proposition formally are equally good candidates for being part of a proposition. The project of a good bit of Aboutness is to use a truthmaker-enriched understanding of meaning to define a robust notion of content-parthood.

The first question you might ask is whether we really need a well-behaved notion of partial content. Is it a crucial tool for making sense of some of the basic ways we talk about what we say and think? Does it have the same kind of fundamental status as notions such as truth, content, and, maybe, reference have?

One of the most important contributions of Aboutness is the sustained case Yablo makes for the importance of partial content. Crudely, we could divide his arguments for the uses of the notion into two kinds: those that are based on some kind of application to another area of philosophy (most notably metaphysics, epistemology, and philosophy of science), and those based on considerations of how we think and speak generally. I will focus here on the latter.

The following pattern of inferences is an example of the kind of ordinary thought that Yablo thinks ought to be captured by a notion of partial content:Footnote 11

-

(1)

Mary thinks it’s raining and cold, Lisa thinks it’s raining but warm.

\(\rightarrow\) Mary and Lisa agree that it’s raining.

-

(2)

Mary thinks it’s snowing, Lisa thinks it’s raining.

\(\not \rightarrow\) Mary and Lisa agree it’s raining or snowing.

Yablo’s explanation for the difference between (1) and (2) is as follows: it’s raining and cold has as a part it’s raining, and it’s raining but warm has as a part it’s raining. Since there is a common part to what Mary and Lisa are thinking, they agree about that part in (1). On the other hand, it’s raining or snowing is not a part of it’s raining or it’s snowing, so there is no common part that Mary and Lisa agree about in (2)

Now one might think that the contrast between (1) and (2) can be explained pragmatically. Certainly, similar arguments do admit of pragmatic explanations:

-

(3)

Mary likes ice-cream and peanuts.

\(\rightarrow\) Mary likes peanuts

-

(4)

Mary likes ice-cream.

\(\not \rightarrow\) Mary likes ice-cream or peanuts.

There is a clear sense that inference in (3) is more intuitive than that in (4), although both are classically valid. There is an simple pragmatic explanation of this fact, though. An assertion of Mary likes ice-cream or peanuts would almost always lead to the implicature that the speaker does not know whether Mary likes ice-cream or peanuts. This implicature might explain why we do not intuitively regard the inference in (4) as valid. However, no such reasoning can apply to (2). For there are no intuitively problematic implicatures of Mary and Lisa agree it’s raining or snowing: the grounds for uttering it need not be that Mary or Lisa agree about either disjunct. Thus, standard Gricean considerations about the meaning and implicatures of disjunction do not explain the contrast between (1) and (2).

It would not be good, however, if this motivation for a robust notion of partial content rested entirely on the behavior of explicit disjunction. For we know that disjunctions exhibit a variety of rather puzzling behaviour such as free-choice implications and simplification of disjunctive antecedents.Footnote 12 What happens if we rephrase the inference to a disjunction by use of existential quantification instead? Unfortunately, in this case the intuitions that Yablo relies on are not as straightforward:Footnote 13

-

(5)

Mary thinks Bill stole the cookies. Lisa thinks Ted stole the cookies.

\(\rightarrow\) Mary and Lisa agree that someone stole the cookies.

\(\not \rightarrow\) Mary and Lisa agree that Ted or Bill stole the cookies

If we think that agreement requires agreeing on a part, then someone stole the cookies is a part of Ted stole the cookies. Unfortunately, this suggests that what is going on in (1) and (2) does depend on the particular linguistic form of disjunction.

Nonetheless, the fact that sentences like Bill stole the cookies and Ted stole the cookies have something in common is not a bad conclusion. For we might think Bill stole the cookies can itself be canonically decomposed into conjunctive parts such as there was an event of cookie stealing and Bill was the agent of the event. So we might think that someone stole the cookies is a decent way of expressing this first conjunctive part, explaining the pattern in (5). Of course, considerations like this suggest that there may be a certain hyperintensionality in truthmakers (something Yablo sometimes allows and Fine, in related work, pushes). It might be that while someone stole the cookies is intensionally equivalent—in a given domain—to a disjunction, we treat it as having different truthmakers (on at least one reading).

I hope the above discussion gives the reader a sense of some of the difficulties in working out an adequate notion of partial content to explain the kind of inferences we make about shared content. It seems likely to me that the standard stock of equipment—LS subject matters and neo-Gricean pragmatics—simply doesn’t have the resources for a fruitful account of this data. It is a bit harder to see whether Yablo’s account of partial content—which in turn relies on truthmakers and subject matters—is ultimately what is needed here. But, at the least—as with presuppositions—it gives us the vocabulary to make the kinds of distinction that seem crucial.

5 Generality

I’ve covered a hodge-podge of different topics: I’ve discussed how Yablo’s notion of subject matter relates (and fails to relate) the similar notions in the linguistics literature, I suggested the kind of distinctions made by his apparatus of truthmakers may play an important role in understanding the origins of presupposition, and I tried to sketch one kind of intuitive reasoning that motivates the notion of partial content as well as suggesting the kinds of problems that this gets us into. In doing so, I’ve tried establish three things: (a) the conceptual apparatus Yablo introduces has mostly superficial resemblance to the standard linguistic machinery for covering aboutness, (b) the apparatus can be productively applied to many topics he does not discuss, and (c) his motivations for the apparatus include the ability to cover an interesting pattern of reasoning not covered by standard theories.

I should close by admitting that my perspective on this book here is rather idiosyncratically affected by my own interests. Part of the appeal of the book, though, is that its breadth and generality means that it will provide fruitful ideas across many different areas.

Notes

Some, like me, even talk about discourse referents, context change potentials, and so on, but these innovations are largely orthogonal to Yablo’s.

The appendix, incidentally is not in the book, but at http://www.mit.edu/~yablo/home/Papers_files/aboutness%20theory.

For Lewis it was an equivalence relation, Yablo gives convincing arguments why this is too restrictive a structure for his purposes.

The closest thing to a Yablovian subject matter for a single sentence is its focus value (see, e.g., Rooth 1985). So, for example, the sentence ‘LUCINDA ate the cheese’ has a focus value equivalent to the question ‘Who ate the cheese?’ Comparing focus values with Yablo’s subject matters would take us too far afield, but suffice it to say that neither reduces to the other though there are some overlaps.

In my view this is not because trivalence itself is suspect, but rather because it might be difficult to use trivalence too much in explaining different linguistic phenomena. It turns out that many uses of trivalence found in the literature are mutually incompatible (Soames 1989; Rothschild 2014; Spector 2015; Križ 2015).

Of course, the divisibility of the content is itself a matter of considerable debate in epistemology. However, at the least, we can all accept that the factive entailment (that p is true) can be true without John bearing any epistemic relation to p. Any further division would be rejected by those who follow Williamson (2000) in thinking that knowledge is unanalysable.

This strategy can be generalized beyond ‘know’: the king of France is bald’ both asserts the existence of a king of France and says that he is bald, ‘John stopped smoking’ both says that John used to smoke and that he doesn’t now....

Well, to be fair, you can’t divide a proposition it into more partitions than there are worlds in it. I leave as an exercise to the reader the calculation of the number of partitions.

Again note that there is no requirement that the conjuncts be logically independent: so this view is tenable for those who argue for the unanalyzability of knowledge.

For more examples see pp. 12–14.

To take this argument the opposite direction: Yablo’s program has much potential to explain these sorts of recalcitrant idiosyncrasies of natural language (see also, Fine 2012).

Yablo tells me that Timothy Williamson made a similar point during the Locke Lectures.

References

Abrusan, M. (2011). Predicting the presuppositions of soft triggers. Linguistics and Philosophy, 34, 491–535.

Abusch, D. (2010). Presupposition triggering from alternatives. Journal of Semantics, 27(1), 37–80.

Chemla, E. (2008). Similarity: Towards a unified account of scalar implicatures, free choice permission and presupposition projection, http://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/WI1ZTU3N/Chemla-SIandPres.html, unpublished manuscript, ENS

Fine, K. (2012). Counterfactuals without possible worlds. The Journal of Philosophy, 109, 221–246.

Fine, K. (2015a). A theory of truth-conditional content I, manuscript. New York: NYU.

Fine, K. (2015b). A theory of truth-conditional content II, manuscript. New York: NYU.

Fine, K. (forthcoming). Truthmaker semantics. In Blackwell Companion to the Philosophy of Language. Blackwell

Grice, P. (1981). Presupposition and conversational implicature. In P. Cole (Ed.), Radical pragmatics. New York: Academic Press.

Groenendijk, J., & Stokhof, M. (1984). Studies in the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam.

Hamblin, C. (1958). Questions. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 36, 159–168.

Hamblin, C. (1973). Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language, 10, 41–53.

Karttunen, L. (1977). Syntax and semantics of questions. Lignuistics and Philosophy, 1, 3–44.

Križ, M. (2015). Aspects of homogeneity in the semantics of natural language. PhD thesis, University of Vienna.

Lewis, D. (1988). Statements partly about observation. In Papers in philosophical logic, Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, C. (1996). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. OSU Working Papers in Linguistics 49.

Rooth, M. (1985). Association with focus. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Rothschild, D. (2014). Capturing the relationship between conditionals and conditional probability with a trivalent semantics. Journal of Applied Non-Classical Logics, 24(1–2), 144–152. doi:10.1080/11663081.2014.911535.

Schlenker, P. (2006). Transparency: An incremental theory of presupposition projection, manuscript

Soames, S. (1989). Presuppositions. In D. Gabbay & F. Guenther (Eds.), Handbook of Philosophical Logic (Vol. IV, pp. 553–616). Dordrecht: Springer.

Spector, B. (2015). Multivalent semantics for vagueness and presupposition. Topoi, 35, 45–55.

Stalnaker, R. (1974). Pragmatic presuppositions. In M. K. Munitz & D. K. Unger (Eds.), Semantics and philosophy (pp. 197–213). New York: NYU.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: OUP.

Wilson, D. (1975). Presupposition and non-truth-conditional semantics. Cambridge: Academic Press.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Kit Fine and Stephen Yablo for discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rothschild, D. Yablo’s semantic machinery. Philos Stud 174, 787–796 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0759-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0759-3