Abstract

Background

Low medication literacy is prevalent among older adults and is associated with adverse drug events. The Medication Literacy Test for Older Adults (TELUMI) was developed and content validated in a previously published study.

Aim

To evaluate the psychometric properties and provide norms for TELUMI scores.

Method

This was a cross-sectional methodological study with older adults selected from the community and from two outpatient services. Descriptive item-analysis, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), item response theory (IRT), reliability, and validity analysis with schooling and health literacy were performed to test the psychometric properties of the TELUMI. The classification of the TELUMI scores was performed using percentile norms.

Results

A total of 344 participants, with a mean age of 68.7 years (standard deviation = 6.7), were included; most were female (66.6%), black/brown (61.8%), had low schooling level (60.2%) and low income (55.2%). The EFA pointed to the one-dimensional structure of TELUMI. A three-parameter logistic model was adopted for IRT. All items had an adequate difficulty index. One item had discrimination < 0.65, and three items had an unacceptable guessing index (< 0.35) and were excluded. The 29-item version of TELUMI had excellent internal consistency (KR20 = 0.89). There was a positive and strong association between TELUMI scores and health literacy and education level. The scores were classified as inadequate medication literacy (≤ 10.0 points), medium medication literacy (11–20 points), and adequate medication literacy (≥ 21 points).

Conclusion

The results suggest that the 29-item version of TELUMI is psychometrically adequate for measuring medication literacy in older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact statements

-

The TELUMI may be used for pharmacoepidemiological research, allowing more accurate measures of medication literacy in older adults, to understand its relationship with adherence and self-efficacy.

-

The TELUMI can be used in pharmaceutical clinical practice to identify the need for strategies to improve medication literacy and the effectiveness and safety of medication use in older adults.

Introduction

Medication literacy refers to cognitive and social skills to access, understand, critically evaluate, communicate, and calculate medication information to make informed decisions about drug therapy [1,2,3,4]. Low medication literacy is highly prevalent among older adults due to different age-related changes, including deteriorated cognition, loss of visual and hearing acuity, and decreased learning ability and memory [5,6,7]. Medication literacy decreases with age, compounded by the frequent and complex use of medication by this population. Therefore, older adults are one of the most important targets for interventions to improve medication literacy skills [7]. With sufficient literacy, older adults can understand and act appropriately on medication information, impacting medication adherence and preventing medication use problems [3].

Despite the significant importance of medication literacy in older adult care, no instrument specifically validated to measure this construct in this population is available, as shown by our scoping review on medication literacy published in 2021 [8]. Between 2022 and 2024, two instruments were developed to measure medication literacy. However, they have not been psychometrically validated [9, 10]. The Medication Literacy Test for Older Adults (TELUMI) was developed to bridge this gap. TELUMI assesses the ability of older adults to access, understand, communicate, calculate, and evaluate medication-related information. It is a performance-based measure of medication literacy with 33 items divided into eight medication use scenarios [11]. The items theoretically represent the four dimensions (functional, communicative, critical, and numeracy) of medication literacy [4, 11]. TELUMI is a type of paper and pencil test in a book format. The instrument development and content validation process involved a stepwise approach described earlier [11].

Aim

This study was conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of TELUMI and provide preliminary local norms for instrument scoring.

Ethics approval

The Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais approved the study (CAAE: 19835219.4.0000.5149) in September/2019. All human research procedures followed the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Only individuals who signed the informed consent form participated in the study.

Method

Design and setting

This was a cross-sectional methodological study conducted with older adults selected from the community and from two multispecialty outpatient services of two public teaching hospitals in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Participants were recruited from November/2021 to August/2022.

Participants

The individuals were eligible if they met the following criteria: age ≥ 60 years (per the definition of older adults proposed by the United Nations for developing countries) [12]; self-reported ability to read; and lack of cognitive, visual, or hearing impairments that hamper communication with the interviewer.

Participants were selected by convenience. In the two outpatient services, patients were approached while waiting for their medical appointment. In the community, participants were selected by invitation; an included individual could later nominate another potential participant.

The estimated sample size considered 10 individuals per item of the instrument being tested (33 items), the suggested ratio for conducting factor analysis [13].

Data collection

Face-to-face interviews were held by six trained pharmacy graduate students using a structured form. Interviewers were trained in face-to-face group meetings to practice administering the interview questionnaire, including TELUMI.

The following self-reported information was collected: sociodemographic (gender, age, race, education, marital status, income, occupation, living alone, number of people living with), communication (visual and hearing impairment that did not hinder communication with the interviewer), clinical conditions (self-perception of health, number of comorbidities), medication use (use of prescription or over-the-counter medications, the number of medications in use), cognition, and health literacy.

Visual and hearing impairment were measured by two communication questions extracted from the Clinical-Functional Vulnerability Index-20 [14].

Self-perception of health was measured using a 5-point Likert scale extracted from the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) tool [15], which was categorized as positive (excellent, very good, good) or negative (fair, poor).

The number of self-reported comorbidities was categorized as having or not having multimorbidity, which was classified as the presence of two or more comorbidities [13].

The number of medications used was categorized into polypharmacy, defined as the use of five or more medications [16].

Cognition was measured by the Brazilian version of the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument – Short Form (CASI-S). The total score ranged from 0 to 33 points. The cutoff score for cognitive impairment was ≤ 23 for individuals younger than 70 years and ≤ 20 for individuals 70 years and older [17].

Health literacy was measured by the Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Portuguese-Speaking Adults (SAHLPA). The total score ranged from 0 to 18 points [18]. There is no cutoff point for SALHPA scores. Therefore, total scores were classified as low, medium, and high health literacy per the P25 and P75 percentiles.

For the TELUMI application, the interviewer read the instrument aloud. The participant had a copy of the instrument, following the reading with the interviewers. Correct and incorrect/I don’t know answers were scored with one and zero points, respectively. The total scores ranged from 0 to 33 points [11]

Analysis

The database was created in Epi Info (version 7.2.4.0). The consistency analysis was based on descriptive statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed with RStudio (version 1.4.1106) using the packages “summarytools”, “psych”, “polycor”, and “mirt”. The preliminary local percentile norm for TELUMI scores was determined using the Percentile Norms [19].

Descriptive statistics were used to report the sample characteristics. Descriptive item-analysis, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), item response theory (IRT), reliability, and convergent validity analysis were performed to test the instrument’s psychometric properties.

Descriptive item-analysis

The descriptive item-analysis included the mean, standard deviation and normality distribution. The normality of the distribution of each item was evaluated by skewness and kurtosis, and values between −2 and + 2 were considered acceptable [20].

Exploratory factor analysis

EFA was performed to analyze the internal structure of TELUMI. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS) were used to test the adequacy of the data for factor analysis. KMO index was classified as mediocre (0.5–0.7), good (0.7–0.8), great (0.8–0.9), or superb (> 0.9). Significance in BTS (p < 0.05) indicated that the data were suitable for EFA [20].

Parallel analysis, Cattell’s scree test, and the Very Simple Structure (VSS) test were used to determine the number of factors to be extracted. A tetrachoric correlation matrix was used to perform EFA using weighted least squares (considering the dichotomous characteristic of the variables) and oblimin rotation (considering the multidimensional conceptual model and a correlation between the factors). Items with loadings > 0.3 for only one factor were retained. Items with similar loadings in more than one factor (complex items) were excluded [21].

Item response theory

Unidimensional latent trait models were performed to estimate IRT parameters. The Rasch model and the Birnbaum logistic response models [two (2PL) and three-parameter model (3PL)] for dichotomous items were performed [22]. The models were compared by ANOVA and tested for their fit to the data by the M2 model fit statistic [23].

Items were classified according to their discrimination (0.01–0.34 very low; 0.35–0.64 low; 0.65–1.34 moderate; 1.35–1.69 high; > 1.70 very high), difficulty (< −2 very easy; −2 to −0.5 easy; −0.5 to 0.5 medium; 0.5–2 hard; > 2 very hard), and guessing scores (≤ 0.35 acceptable, > 0.35 unacceptable) [24]. Items with discrimination < 0.65, difficulty < −3 or > +3, or guessing scores > 0.35 were excluded.

Reliability

Reliability was analyzed by internal consistency using the Kuder–Richardson formula 20 (KR20), a particular case of Cronbach’s alpha for dichotomous data. A KR20 ≥ 0.70 was considered adequate [25].

Validity analysis with education and health literacy

TELUMI scores were assessed for their association with health literacy (SAHLPA scores) and education (≤ 8 years and > 8 years). Educational level is a relevant determinant of medication literacy, and health literacy and medication literacy are related constructs. Therefore, a positive, direct, and at least moderate association between the TELUMI scores and both variables was expected since the higher the educational and health literacy, the greater the level of medication literacy should be [4]. As the variables did not show a normal distribution according to the Shapiro‒Wilk normality test, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used in the analyses with the SAHLPA scores, and the Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney test was used in the analyses with schooling levels.

Percentile norms

Determination of the preliminary local norm for TELUMI scores was performed using the percentile norm, based on the determination of the percentiles of the instrument’s total scores using the Bayesian method [19]. We considered that 50% of individuals had usual literacy scores to propose the categorization of scores. Therefore, the P25 and P75 percentiles were chosen as thresholds for the following categories: low medication literacy level: scores ≤ P25; medium medication literacy level: P25 < scores < P75; and high medication literacy level: scores ≥ P75.

Results

Participant characteristics

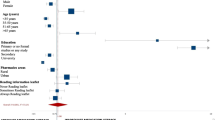

A total of 431 individuals were approached to participate in the study, and 344 were included (Fig. 1).

The mean age of the participants was 68.7 years [standard deviation (SD) = 6.7], and most were female (66.6%), black or brown (61.8%), had a low education level (60.2%), had a low income (55.2%), had preserved cognition (80.8%), had a positive perception of their health (65.6%), used medication (91.8%), and had a low to medium level of health literacy (70.6%) (Table 1).

The mean number of comorbidities was 3.0 [SD = 1.7, minimum (min.) = 0.0; maximum (max.) = 7.0]. The mean number of medications used was 4.5 (SD = 2.9, min. = 0.0; max. = 15.0).

Psychometric evaluation

Descriptive item-analysis

The mean total TELUMI score was 18.4 [SD = 7.4; min. = 0.0; max. = 33.0]. The mean application time was 30.9 min (SD = 10.0; min. = 8.0; max. = 89.0).

In general, the SD values were not close to zero, which was a good indication of adequate variability of the items. Skewness and kurtosis values were considered acceptable for all items (Table 2).

Exploratory factor analysis

The sample was considered adequate for factor analysis according to BTS (chi square = 2897.063, p < 0.001, degrees of freedom = 528) and the KMO index (0.91).

The parallel analysis and Cattel’s scree plot test suggested that two factors to be extracted (Supplement Figure S1 and Figure S2). The VSS pointed out one, two, or four factor solutions (Supplement Figure S3). EFA was performed for the three different factor structure solutions (1, 2, and 4 factors), which were subsequently compared.

The four-factor solution was carried out first because the conceptual model proposes four dimensions for medication literacy. The grouping of items in the four-factor structure was not consistent, as items of different theoretical dimensions were mixed into different factors (Supplement—Figure S4). In the two-factor solution, items theoretically classified as “numeracy”, except for one, were grouped into one factor together with some items of the “critical” and “functional” dimensions. The other factor mixed functional, communicative, and critical literacy items (Supplement—Figure S5). Moreover, some items were considered complex, with similar loadings for both factors. Therefore, EFA pointed to the one-dimensional structure of TELUMI. The loadings for the one-dimensional solution were > 0.3 for all items, which were all tested in the IRT (Table 2).

Item response theory

ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference between the unidimensional latent trait models, with 2PL being better than Rasch and 3PL being better than 2PL. Therefore, the 3PL was chosen to estimate the IRT parameters for TELUMI.

Only one item (item 32) showed discrimination < 0.65 and was excluded from the test. All other items showed adequate discrimination potential, with most presenting a high (4 items) or very high (25 items) index and three presenting a moderate (3 items) index. Three items (5, 7, and 10) had unacceptable guessing indices (> 0.35) and were excluded from TELUMI. All items had an adequate difficulty index; most of them had a medium level of difficulty (16 items), and the others were easy (8 items) or hard (9 items) (Table 2). For the remaining 29 items, the distribution per difficulty level was 27.6% (8 items) easy, 44.8% (13 items) medium, and 27.6% (8 items) hard.

After removing the items, TELUMI had 29 items (9 understand, 2 access, 1 communicate, 8 analyze, and 9 calculate) (Supplementary material).

Reliability

The KR20 result (0.89) indicated excellent internal consistency of the 29-item version of the instrument.

Validity analysis with education and health literacy

There was a significant, positive, and strong association between TELUMI scores (29-item version) and SAHLPA scores (rho = 0.76; p < 0.00) and between TELUMI scores and education level (w = 2331, p < 0.00), which points to the validity of the instrument [26].

Percentile norms

The P25 for the total TELUMI (29-item version) score was 10 points; the P75 was 20.3, which was between P72 (20) and P78 (21). As TELUMI scores are whole numbers, we adopted P78 (21 points) as the cutoff point for adequate literacy levels. Therefore, we considered the following: low medication literacy level: scores ≤ 10.0 points; medium medication literacy level: 11 points ≥ scores ≤ 20 points; and high medication literacy level: scores ≥ 21 points (Table 3).

Discussion

Statement of key findings

This study evaluated the psychometric proprieties of TELUMI. The instrument had high internal consistency, items with adequate factor loading for a new instrument and adequate discrimination and guessing parameters. Moreover, we achieved an approximate ratio of 50% medium difficulty items, 25% easy items, and 25% difficulty items.

While four dimensions are proposed in the conceptual model of medication literacy used as the framework for developing TELUMI [4], the EFA supported a one-dimensional structure for the instrument, which can be explained by the complexity of the construct. The theoretical dimensions of medication literacy comprise progressive skills for using medication information [4, 25, 27]. This progressivity makes it challenging to operationalize items that are not complex and have a clear separation between each dimension they determine. The one-factor structure implies that it is possible to generate a single score that reflects medication literacy as a global construct. Therefore, it is not possible to generate specific scores for each of the four dimensions proposed theoretically. However, while not properly adjusted, the two-factor EFA tended to a aggregate the numerical items (numeracy) with critical analysis items (critical dimension), which may indicate a unifying factor between items that require more advanced skills. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is required to confirm the one-dimensional structure of the instrument.

Studies for the validation of other instruments indicate that the dimensions conceived in the preliminary version of the instrument were not the same as those in the final version of the instrument [21, 28, 29]. For example, a study that evaluated the psychometric characteristics of the Chinese Medication Literacy Measure originally proposed four dimensions to the instrument. However, the results of the exploratory factor analysis supported a one-factor structure for the instrument [30].

The combination of items from the 29-item version of TELUMI appears to adequately represent the skills encompassed in the definition of medication literacy [4]. However, only three items initially designed to represent access and communicate skills remained in the instrument. A possible explanation is difficulty in operationalizing the communicative dimension of medication literacy, especially in a test-type instrument in paper and pencil format. This difficulty was previously identified during the TELUMI development and content validation study [11].

The associations between TELUMI scores and educational level and health literacy are another indication of the instrument’s validity. Educational level is one of the most relevant determinants of medication literacy [3, 4, 10, 26]. The knowledge base acquired through formal education influences an individual’s ability to use and address medication problems [3]. A study that analyzed medication literacy in a cohort of pharmacy customers in Spain observed an increase in adequate medication literacy with higher academic levels of the participants, and secondary school education was related to higher medication literacy scores [26]. Medication literacy and health literacy are different but conceptually related constructs, and medication literacy can be considered an application of health literacy in medication use [4, 31,32,33]. Individuals with low health literacy are also expected to have low medication literacy and, therefore, more difficulty using their medications. Thus, a linear association was expected between TELUMI scores, health literacy, and educational level.

The TELUMI local norm allows for the interpretation of the instrument scores and the classification of older adults by medication literacy level. The lack of a classification of the scores would hamper the interpretation of the results, limiting the application of the instrument in epidemiological research and clinical context. Therefore, the preliminary score classification can help pharmacists and other healthcare professionals identify which individuals need interventions to improve their medication use skills and the effectiveness and safety of their drug therapy.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study has strengths and limitations. The first limitation is that it was impossible to perform a CFA, as it would require a different sample from that used in the EFA. Another limitation was the small number of items from the access and communicate subdimensions [4].

The strengths of this study was the use of the IRT to assess the psychometric characteristics of TELUMI, and the proposition of the instrument’s local norm, which facilitates the interpretation of its scores. However, it is essential to note that this is a preliminary norm since the sample included in this study is not representative of the target population despite the relatively heterogeneous sample, which included individuals from the community and outpatients. Finally, this was the first attempt to validate an instrument to measure medication literacy in older adults.

Interpretation

The availability of TELUMI can contribute to improve pharmacoepidemiological studies, allowing more accurate measures of medication literacy. In the context of older adults' care, TELUMI can expand the understanding of the process of medication use among older adults. In clinical practice, TELUMI can be used by clinical pharmacists and health care professionals to identify the need for strategies to improve medication literacy and the effectiveness and safety of medication use by older adults.

Further research

To consolidate the findings of this study, future research should test the psychometric characteristics of the instrument on larger samples, carry out CFA to confirm its unidimensional structure, and include additional items to represent the access and communicate subdimensions. Furthermore, longitudinal studies can test the stability of the instrument over time.

Conclusion

The results suggest that the 29-item version of TELUMI is psychometrically adequate for measuring the ability of older adults to access, understand, communicate, calculate, and evaluate medication-related information.

References

Pouliot A, Vaillancourt R, Stacey D, et al. Defining and identifying concepts of medication literacy: an international perspective. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14:797–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.11.005.

Pouliot A, Vaillancourt R. Medication literacy: why pharmacists should pay attention. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2016;69:335–6. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v69i4.1576.

Gentizon J, Bovet E, Rapp E, et al. Medication literacy in hospitalized older adults: concept development. Health Lit Res Pract. 2022;6:e79–83. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20220309-02.

Neiva Pantuzza LL, Nascimento E, Crepalde-Ribeiro K, et al. Medication literacy: a conceptual model. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18:2675–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.06.003.

Cutilli CC. Health literacy in geriatric patients: an integrative review of the literature. Orthop Nurs. 2007;26:43–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006416-200701000-00014.

Chesser AK, Keene Woods N, Smothers K, et al. Health literacy and older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2016;2:233372141663049. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721416630492.

Horvat N, Kos M. Development, validation and performance of a newly designed tool to evaluate functional medication literacy in Slovenia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42:1490–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01138-6.

Pantuzza LLN, Nascimento E, Botelho SF, et al. Mapping the construct and measurement of medication literacy: a scoping review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87:754–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14490.

Gentizon J, Fleury M, Pilet E, et al. Conceptualization and content validation of the MEDication literacy assessment of geriatric patients and informal caregivers (MED-fLAG). J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022;6:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-022-00495-2.

Mei C, Xu B, Cai X, et al. Factors affecting the medication literacy of older adults and targeted initiatives for improvement: a cross-sectional study in central China. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1249022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1249022.

Pantuzza LLN, Nascimento E, Botelho SF, et al. Development and content validation of the medication literacy test for older adults (TELUMI). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;12:105027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.105027.

United Nations. World Population Prospects—Data Booklet [Internet]. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015. Available from: www.unpopulation.org. Accessed 01 Oct 2022

DeVellis RF. Scale development theory and applications. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park (Applied Social Research Methods Series, 26); 2003. ISBN-10 1412980445/ISBN-13 978-1412980449

Moraes EN, Carmo JA, Moraes FL, et al. Clinical-functional vulnerability Index-20 (IVCF-20): rapid recognition of frail older adults. Rev Saúde Publica. 2016;50:81. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1518-8787.2016050006963.

Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, et al. The vulnerable elders survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691–9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:989–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018.

Damascene A, Delicio AM, Mazo DF, et al. Validation of the Brazilian version of mini-test CASI-S. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005;63:416–21. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-282x2005000300010.

Apolinario D, Braga RCOP, Magaldi RM, et al. Short assessment of health literacy for portuguese-speaking adults. Rev Saude Publica. 2012;46:702–11. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102012005000047.

Crawford JR, Garthwaite PH, Slick DJ. On percentile norms in neuropsychology: proposed reporting standards and methods for quantifying the uncertainty over the percentile ranks of test scores. Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;23:1173–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854040902795018.

Muzaffar B. The development and validation of a scale to measure training culture: the TC scale. J Cult Soc Dev. 2016;23:49–58.

Almeida-Brasil CC, Nascimento ED, Silveira MR, et al. New patient-reported outcome measure to assess perceived barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence: the PEDIA scale. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35:e00184218. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00184218.

Birnbaum A. Some latent trait models and their use in inferring an examinee’s Ability. In. Statistical theories of mental test scores, Addison-Wesley, Reading; 1968. ISBN 10: 0201043106 ISBN 13: 9780201043105

Maydeu-Olivares AJH. Limited information goodness-of-fit testing in multidimensional contingency tables. Psychometrika. 2006;71:713–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-005-1295-9.

Baker FB. The basics of item response theory, 2nd edn. ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation; 2001. ISBN-1-886047-03-0

Kuder GF, Richardson MW. The theory of the estimation of test reliability. Psychometrika. 1937;2:151–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02288391.

Plaza-Zamora J, Legaz I, Osuna E, et al. Age and education as factors associated with medication literacy: a community pharmacy perspective. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:501. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01881-5.

Nutbeam D. Defining, measuring and improving health literacy. Health Eval Promot. 2015;42:450–5.

Ping W, Cao W, Tan H, et al. Health protective behavior scale: development and psychometric evaluation. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0190390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190390.

Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, et al. The Warwick-Dinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.

Lin HW, Chang EH, Ko Y, et al. Conceptualization, development and psychometric evaluations of a new medication-related health literacy instrument: the Chinese medication literacy measurement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:6951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17196951.

Vervloet M, van Dijk L, Rademakers JJDJM, et al. Recognizing and addressing limited pharmaceutical literacy: development of the RALPH interview guide. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018;14:805–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.04.031.

Gentizon J, Hirt J, Jaques C, et al. Instruments assessing medication literacy in adult recipients of care: a systematic review of measurement properties. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;113:103785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103785.

Sauceda JA, Loya AM, Sias JJ, et al. Medication literacy in Spanish and English: psychometric evaluation of a new assessment tool. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52:e231–40. https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2012.11264.

Funding

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq [Grant Number 409435/2018–0] and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES) [Finance Code 001]. The sponsors were not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Neiva Pantuzza, L.L., Reis, A.M.M., Botelho, S.F. et al. Medication Literacy Test for Older Adults: psychometric analysis and standardization of the new instrument. Int J Clin Pharm 46, 1124–1133 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-024-01744-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-024-01744-8