Abstract

Background

Within the quality use of medicines (QUM)—which entails timely access to, and the rational use of, medicines—medicine safety is a global health priority. In multicultural countries, such as Australia, national medicines policies are focused on achieving QUM, although this is more challenging among their Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) patients (i.e., those from ethnic minority groups).

Aim

This review aimed to identify and explore the specific challenges to achieving QUM, as experienced by CALD patients living in Australia.

Method

A systematic literature search was conducted using Web of Science, Scopus, Academic search complete, CINHAL, PubMed and Medline. Qualitative studies describing any aspects of QUM among CALD patients in Australia were included.

Results

Major challenges in facilitating QUM among CALD patients in Australia were identified, particularly in relation to the following medicines management pathway steps: difficulties around participation in treatment decision-making alongside deficiencies in information provision about medicines. Furthermore, medication non-adherence was commonly observed and reported. When mapped against the bio-psycho-socio-systems model, the main contributors to the medicine management challenges identified related to “social” and “system” factors, reflecting the current health-system’s lack of capacity and resourcing to respond to patients’ low health literacy levels, communication and language barriers, and cultural and religious perceptions about medicines.

Conclusion

QUM challenges were different among different ethnic groups. This review suggests a need to engage with CALD patients in co-designing culturally appropriate resources and/or interventions to enable the health-system to address the identified barriers to QUM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact statements

-

Critical deficiencies in current clinical practice exist that significantly challenge the QUM in ethnoculturally diverse patients, which go beyond basic language barriers.

-

Pharmacists must proactively seek to recognise the needs of their local communities, implement strategies to overcome barriers, and ensure that the pharmaceutical care needs of CALD patients are appropriately addressed.

-

Health-system managers must provide the capacity and resources to support pharmacists in promoting safe medicine use.

-

Professional organisations and educational institutions must better support the professional development of pharmacists in the context of QUM for CALD patients.

-

There is a clear need for collaboration between healthcare researchers, CALD communities and pharmacists to co-design culturally and linguistically appropriate resources and/or interventions that will help to overcome the identified challenges to QUM.

Introduction

The quality use of medicines (QUM) is a global priority and a key objective of national health policies [1]. In Australia National Medicines Policy requires that healthcare providers (HCPs) adhere to the fundamental principles that promote QUM to optimise patient outcomes [2]. These QUM principles include: ensuring that medicine selection is clinically appropriate for the patient’s condition/s and needs; using medicines rationally alongside non-pharmacological treatment; and ensuring the safe and effective use of medicines [2]. Alongside these QUM principles, medicines safety is officially recognised as national health priority in Australia [1].

In current international pharmacy practice, there are many challenges to achieving QUM, as evidenced by limited access to essential medicines, improper medicine-taking behaviours and medicine-related problems (MRPs) observed in patients [3,4,5,6]. MRPs refer to any adverse issue involving medicines [7], and these may occur at any step along the medicines management pathway (MMP), which includes: decision to treat and prescribe, record medicine order, review of medicine order, issue of medicine, provision of medicine information, distribution and storage of medicine, administration of medicine, monitor for response and transfer of verified information [8]. MRPs are more likely to occur among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) patients mainly due to language barriers but also cultural beliefs [3]. CALD populations are defined as individuals born overseas or with parents or ancestors born overseas for whom English is not the primary language spoken at home [9]. High-income countries, such as the USA, the UK and Australia, have been regarded as preferred destinations for migration. Therefore, in such countries, increasing numbers of CALD patients, with unique needs and expectations, trying to navigate the healthcare system [10].

Australia continues to witness a significant increase in migrant and refugee arrivals [11], rapidly diversifying its ethnic fabric, and presenting several challenges in meeting the pressing health needs of its CALD population. Research to date highlights that CALD patients are more likely to face difficulties in navigating health care due to language and communication barriers, low health literacy (HL), limited social support, and the complexity of Australian healthcare system [12, 13]. In addition, cultural rituals influence health beliefs and behaviours, healthcare system utilisation, engagement in decision-making processes, and perceptions about medicines among CALD patients [14].

Although the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy is well recognised, emerging evidence indicates that CALD patients are more vulnerable to adverse medicine events than the mainstream population [12, 13]. However, limited evidence is available on the type of MRPs experienced by CALD patients in Australia.

Aim

This review aimed to fill this knowledge gap by exploring the challenges to achieving QUM among CALD patients in Australia. The specific objectives were to: identify the nature of MRPs experienced by CALD patients along the steps of MMP, and to identify the factors contributing to these challenges from the patients’ perspective.

Method

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [15]. In August 2022, the following databases were searched: Web of Science, Scopus, Academic Search Complete, CINHAL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PubMed and Medline. The search strategy (Supplementary Table 1) utilised search terms that were compiled using a composite of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms plus keywords used in published literature [14, 16]. The bibliographies of the reviewed literature were also searched. The search timeframe was limited to the year 1999 onwards; the apparent start of QUM research among CALD groups in Australia.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

A phenomenological lens was applied to this review to ensure that it focused on the essence of patient experience. Therefore, only patient-focused qualitative studies were included. Studies that explored any aspect of the QUM and/or MRPs among CALD patients in Australia were eligible for inclusion. Those reporting on tangential topics and/or non-CALD populations, or had other study designs, were excluded (Table 1).

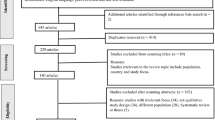

The initial search was conducted by two reviewers (RS, BB), who initially screened all titles and abstracts for relevance. The three authors independently reviewed the remaining studies against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (BB, RS, HH). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and mutual agreement. Figure 1 outlines the search process and study selection.

Data synthesis and analysis

The data extracted were as follows: author(s), publication year, study design/type, setting and sites, sample/study population and key findings regarding MRPs and contributing factors as perceived by the patients. An inductive, and consensus-building process was used to analyse the data; author agreement on categories and themes was attained through iterative process. To categorise MRPs, data extracted from qualitative studies were synthesised via a meta-ethnographic approach [17], using the steps of the MMP [8]. Concerning contributing factors, the emerging key themes were categorised against one of the four components of the bio-psycho-socio-systems model: biological, psychological, social, and health-system factors [18, 19].

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the reviewed studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for qualitative studies to determine the validity of each study’s results, the findings, and their value for research [20]. Two authors conducted the quality assessment independently, with any disagreements resolved by consensus-building discussion. Most studies reported 9 of the 10 CASP checklist items (Table 2).

Results

The initial search returned 685 articles; after removal of duplicates, 236 remained. After screening, 41 articles were subsequently eligible for full-text review. Finally, 17 articles were included in this review, collectively reporting the experiences of participants recruited from a wide range of ethnic communities in Australia, including Chinese [21,22,23,24,25], Vietnamese [22, 26, 27], Greek [21, 25, 26], Italian [21, 26], Arabic-speaking backgrounds [21, 23, 28,29,30], Indian [31], African [32] and other various ethnic backgrounds [33,34,35]. Four studies recruited elderly participants [21, 24, 27, 36], and two recruited refugees [32, 34]. Table 3 describes the characteristics and key findings of the reviewed studies.

Medicine-related problems

Decisions to treat and prescribe

Participants from various ethnic backgrounds reported relatively limited access to treatments, including medicines [22, 23, 28, 32, 34]. In particular, African refugees reported limited access to medicines and pharmacy services [32]. Vietnamese and Chinese patients who were eligible for a pharmacist-led home medicine review (HMR) reported having limited access to this service [22]. In addition, Chinese, Vietnamese and Arabic-speaking participants delayed seeking care from HCPs [23, 28].

Participants from some ethnicities were disengaged in making decisions regarding their preferred treatment and, instead, tended to passively follow instructions from their general practitioners (GPs) [25, 33, 36]. Although some CALD patients expressly preferred herbal and complementary medicines as a treatment option over conventional Western medicines [21, 23, 25], there were wide differences in their use patterns across different cultural groups. Arabic-speaking participants used herbal remedies in combination with prescribed conventional medicines or as a first option for minor illnesses [28, 29]. Chinese and Vietnamese participants used traditional therapies routinely as a first-line option to manage their conditions without consulting their physicians [23, 27]. In contrast, Italian participants reported a preference for prescription medicines, preferring medicines to be administered as suppositories and injections over oral formulations as these were perceived to be more effective with faster onset of action [23]. Among Arabic-speaking participants, religious prayers were used to treat illness, especially in the early stages after diagnosis [37].

Medicines sharing with family members was commonly reported among Chinese, Indian and Arabic-speaking participants [23, 25, 29]. Whilst the overuse of some types of medicines, namely antibiotics, was described among different cultures, this was not observed among Asian participants who considered antibiotics less appealing [35].

Provision of medicine information

Deficiencies in information regarding medicines and their indications, and related problems stemming from this, were prevalent among participants from all ethnic backgrounds [22, 23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 36]. It was noted that Indian participants who had been initially diagnosed with diabetes in their home country (where they could access information in their language) were more deficient in knowledge about diabetes and antidiabetic medicines than participants who were diagnosed in Australia [31]. Overall, all participants—especially Arabic and Italian participants—who had accessed the Australian healthcare system expressed the need for more information to be provided about their medicines [23, 25].

CALD participants relied on accessible sources of information about their medicines and diseases, such as the internet and social media [25, 35]. CALD participants with low HL reported a reliance on family and friends as informational support [25, 33], whilst others preferred using visual aids to help convey medicine-taking instructions [33]. In addition, most participants preferred that written information about their medicines was provided in their language [33, 35, 36].

Administration of medicine (medication adherence)

Five studies reported medication non-adherence as a common MRP, which presented as refusal to initiate prescribed medicines and/or the deliberate discontinuation of prescribed medicines [23, 26, 28, 30, 31]. Some Chinese patients tended to not to have their prescribed medicines dispensed or even stopped the medicine as soon as they were free from symptoms [23]. Similarly, Arabic-speaking participants with asthma reported self-initiated dose reduction and/or cessation of prescribed therapy for fear of side-effects or addiction [28, 31]. Some Indian participants also tended to stop any prescribed medicines after having travelled back to their homeland, reverting back to the use of “Ayurvedic medicines” (traditional herbal medicines in the Indian culture) [31]. Additionally, across some ethnic groups, medication adherence was reduced when observing specific socio-cultural events that affected mealtimes (to which medicine-taking is often aligned), such as during religious rituals, e.g., during Ramadan [30, 31].

Transfer of verified information

Participants across all ethnic groups identified discrepancies in their medicines records, which subsequently adversely impacted the continuity of their care. These discrepancies included different information being recorded in medicines lists across health settings, and was compounded by the reported failure of hospitals to provide discharge summaries to their GPs [24]. This failure resulted in stopping important medicines that were hospital-initiated and/or in unnecessarily continuing temporary medicines [24].

Potential contributing factors

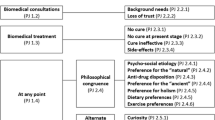

Figure 2 summarises the factors perceived by CALD participants as contributing to MRPs.

Biological factors

Some CALD patients felt that they were at higher risk of experiencing chronic illnesses due to their genetic makeup and lifestyle changes in Australia [38]. CALD participants using polypharmacy were observed to be at increased risk of MRPs [36].

Psychological factors

Several psychological factors, such as a lack of confidence in HCPs who did not speak their language [29] and having lower expectations about pharmacists role in their treatment, likely contributed to MRPs among CALD patients [28]. These factors led some CALD participants to frequently change their GPs, resulting in discontinuity of care [24]. Other psychological factors underpinned patients’ delay in seeking treatment, including the denial of illness, maintain beliefs in destiny/fate, and feeling overwhelmed by other life problems [28].

Low self-efficacy among participants contributed to medicines mismanagement and non-adherence [26, 33]. Medication non-adherence was compounded by distrust in conventional medicines and concerns about side-effects [26, 31, 33]. Participants from Greek, Russian and Italian communities reportedly only took their antihypertensive medicines if they had a high blood pressure reading, due to fear of side-effects [24].

Social factors

Social factors contributing to MRPs arose from social isolation as a result of being a minority group in Australia, where communication and language barriers resulted in limited exposure to healthcare services [21, 23, 26, 28, 29, 32,33,34, 38]. Social networks and support were restricted to family and friends, who became their primary information providers and interpreters during physician consultation [25, 36]. Participants often preferred to consult with physicians who spoke their language [25, 28, 33].

Social isolation was compounded by low HL and insufficient knowledge about medicines and the healthcare system among CALD participants [26,27,28, 33, 34, 36]. Whilst many participants preferred receiving written instructions about their medicines in their native language or pictograms to comprehend medicine instructions [33], they were unaware of the other relevant resources and health services facilities, including freely available health-related information resources and access to interpreting services during HCP consultations [28]. This included a lack of awareness about pharmacy-based services, as highlighted by Vietnamese women who were unaware of the availability of HMR services in Australia [22].

Other socially-embedded factors related to perceptions about the ‘patient-HCP’ relationship. Overall, these studies identified ineffective relationships between patients and HCPs due to the variations in the perceived HCPs’ status across cultures [21, 29, 34, 38]. Arabic-speaking participants passively followed their GPs instructions, strongly depending on GPs as a source of information, and for decision-making about their health [25, 33, 36]. In contrast, Chinese participants preferred to not fully involve their GPs when receiving HMR [22], and instead regarded their herbalists as being vital to promoting QUM [23]. Alongside the low awareness of their role in medicines management [34, 38], pharmacists were reportedly least likely to be consulted by CALD communities [21, 23, 34]..

Other social factors were more specific to their cultures, such as medicine beliefs and misconceptions [21, 23, 26, 28, 29, 31, 33]. Some CALD participants perceived Western medicines as ineffective and unsafe [21, 23, 28, 29]. Asian participants perceived antibiotics as such ‘strong’ medicines that they could interfere with the body’s humoral balance [35], and, therefore, perceived herbal medicines as a more acceptable option [21, 23, 28, 29]. The perceived value of herbal medicines and their contribution to MRPs, varied across the different ethnic groups. Chinese and Vietnamese participants strongly believed in the efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) than Western ones due to their prior experiences with TCM [23, 27, 33]. Older Vietnamese women believed that HCPs did not support combining traditional and Western treatments and, therefore, tended to combine these medicines without consulting their physicians—sometimes, abandoning care from their HCP altogether [27]. Arabic-speaking participants believed in herbal medicines to a lesser extent than Chinese participants [23].

Even among CALD participants who accepted using conventional medicines, travelling back to home countries sometimes resulted in using local healthcare services. Some participants recognised this as a potential contributor to antibiotic resistance [35], noting that importing antibiotics from overseas could lead to overuse, duplication, and increased risk of side-effects [35].

Other socio-cultural factors contributed to medication non-adherence and/or the refusal to seek help from HCPs. These included the social stigma associated with certain diseases in some cultures, such as diabetes and asthma in Arabic and Indian Cultures [28, 29, 31]. Religious beliefs such as dependence on faith for treating health problems [29, 30], preferences for treatment by same-sex HCPs [21], and abidance to religious practices, such as fasting during Ramadan, were also identified as contributing to non-adherence. For some Muslim participants, there was low awareness about exemptions for fasting for certain patients, compounded by low awareness about the role of pharmacists in managing medicines during fasting [30].

System-related factors

CALD participants highlighted the apparent limited availability of information about medicines and illnesses in their native languages [25, 36]. Underutilisation of interpreter services was common, mainly due to perceived insufficient availability of such services [25, 28, 32, 34] and/or a lack of trust in interpreters [25, 28].

Other system-related factors were attributed to HCPs' lack of proper communication with CALD patients [38]. Some participants reported that HCPs, including pharmacists, did not seek to understand their medicine-related challenges, such as needing to manage medicines schedules whilst fasting during Ramadan [30]. Some CALD participants also reported difficulties navigating the unfamiliar Australian healthcare system [28, 32]. Specific differences around access to medicines within Australian health-system were also noted by CALD patients: some Chinese participants described the high cost of medicines [21], whereas, Italian participants reported limited availability of European medicines in Australia [23].

Discussion

Main findings

This review has identified a range of problems concerning the QUM among ethnic cohorts in Australia, such as a lack of appropriate medicines information, medication non-adherence and limited access to healthcare facilities [26,27,28, 33, 34, 36]. These problems were not only due to language and communication barriers, but also due to overall low HL and various cultural factors [21, 23, 26, 28, 29, 32,33,34, 38].

Strengths and weaknesses

This is the first systematic review to explore and identify CALD patients’ experiences with MRPs and their possible contributing factors, aiming to inform future interventions to promote QUM in Australia. This review has several limitations. Some studies comprised mixed ethnocultural participant groups and did not separately report findings for each ethnicity [21, 22, 24, 25]. One study included only patients who could communicate in English [35]. Due to these limitations, our findings may not be transferable to all ethnocultural populations in Australia. Furthermore, the included studies varied in terms of setting, the definition of MRPs, and which aspect of the QUM was targeted. Future research should include a comprehensive investigation of MRPs among each ethnic community.

Interpretation and further research

The most common QUM issues among CALD patients in Australia were insufficient medicine information, medication non-adherence, and limited access to health services [26,27,28, 33, 34, 36]. This complements the findings of review on CALD patients in the UK, which showed that CALD patients were more likely to experience MRPs compared to the general population [14]. Further, this review has also shown that low HL was prevalent among CALD communities, as distinct from illiteracy in English, noting that providing culturally-competent care or overcoming language barriers through interpreting services cannot alone address poor HL among CALD patients [39]. Future studies should focus on designing targeted interventions to address low health and medicine literacy among CALD patients [13, 33, 39, 40].

Previous reviews have highlighted that medicines use practices differ among CALD groups [3, 14, 16]. This review reinforces that traditional medicines vary in their importance across different cultures. Some Vietnamese and Chinese patients were reluctant to access health-system and/or used traditional treatments without consulting their physicians for fear of disapproval because they believed that Australian GPs dismissed traditional medicines as effective treatment options [27]. Consistent with the findings from a previous review among Pakistani patients, HCPs should be more aware of CALD patients' cultural beliefs and practices, including traditional medicines use, rather than dismissing or ignoring these beliefs [16]. Self-diagnosis and self-treatment using traditional medicines was the first-line option for most CALD patients in this review. The literature suggests that co-design interventions, that may take into account these contributing factors, might help in any country that intends to promote QUM in these cohorts [41,42,43]. Although other countries may not have specific definitions and initiatives of QUM, the findings derived from the Australian research could be replicated in other international healthcare systems.

Conclusion

This review offers much-needed evidence into the QUM and MRPs experienced by CALD patients in Australia. The review shed light on the necessity to explore and address medicine-related challenges of each ethnicity separately. The findings of this review have significant implications for clinical practices and future research to involving patients in co-designing culturally appropriate strategies/resources to enhance QUM.

References

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. 2019. https://www.psa.org.au/medicine-safety-to-be-the-10th-national-health-priority-area/. Accessed 21 Jan 2023.

McLachlan AJ, Aslani P. National Medicines Policy 2.0: a vision for the future. Aust Prescr. 2020;43(1):24–6. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2020.007.

Nørgaard L, Cantarero-Arévalo L, Håkonsen H. The meeting between ethnic minorities, medicine use and the Nordic countries: an overview of theory-based intervention studies and lessons learned. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.02.073.

Pearson SA, Pratt N, de Oliveira Costa J, et al. Generating real-world evidence on the quality use, benefits and safety of medicines in Australia: History, challenges and a roadmap for the future. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413345.

Bates DW. Preventing medication errors: a summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(14 Suppl 9):S3–9; quiz S24–6. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp070190.

Chauhan A, Walton M, Manias E, et al. The safety of health care for ethnic minority patients: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01223-2.

Gordon KJ, Smith FJ, Dhillon S. The development and validation of a screening tool for the identification of patients experiencing medication-related problems. Int J Pharm Pract. 2005;13(3):187–93. https://doi.org/10.1211/ijpp.13.3.0004.

Stowasser DA, Allinson YM, O’Leary M. Understanding the medicines management pathway. J Pharm Pract Res. 2004;34(4):293–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jppr2004344293.

Pham TTL, Berecki-Gisolf J, Clapperton A, et al. Definitions of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD): a literature review of epidemiological research in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020737.

Singh M, de Looper M. Australian health inequalities: birthplace. Canberra: AIHW; 2002.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Census reveals a fast changing, culturally diverse nation 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/Media%20Release3. Accessed 21 Jan 2023.

Schwappach DL, Meyer Massetti C, Gehring K. Communication barriers in counselling foreign-language patients in public pharmacies: threats to patient safety? Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(5):765–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-012-9674-7.

Herrera H, Alsaif M, Khan G, et al. Provision of bilingual dispensing labels to non-native english speakers: an exploratory study. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019;7(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010032.

Alhomoud F, Dhillon S, Aslanpour Z, et al. Medicine use and medicine-related problems experienced by ethnic minority patients in the United Kingdom: a review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(5):277–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12007.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Saleem A, Steadman KJ, Fejzic J. Utilisation of healthcare services and medicines by Pakistani migrants residing in high income countries: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(5):1157–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0840-4.

Sattar R, Lawton R, Panagioti M, et al. Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: a guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w.

Bunge M. How does it work?: The search for explanatory mechanisms. Philos Soc Sci. 2004;34(2):182–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393103262550.

Buchman DZ, Skinner W, Illes J. Negotiating the relationship between addiction, ethics, and brain science. AJOB Neurosci. 2010;1(1):36–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740903508609.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Qualitative) Checklist 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. Accessed 22 Jan 2023.

Quine S. Health concerns and expectations of Anglo and ethnic older Australians: a comparative approach. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1999;14(2):97–111. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006616230564.

White L, Klinner C. Medicine use of elderly Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants and attitudes to home medicines review. Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18(1):50–5. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY10099.

Bolton P, Hammoud S, Leung J. Issues in Quality use of medicines in two non-english speaking background communities. Aust J Prim Health. 2002;8(3):75–80. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY02046.

Blennerhassett J, Hilbers J. Medicine management in older people from non-english speaking backgrounds. J Pharm Pract Res. 2011;41(1):33–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2055-2335.2011.tb00063.x.

Shaw J, Zou X, Butow P. Treatment decision making experiences of migrant cancer patients and their families in Australia. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(6):742–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.01.012.

Williams A, Manias E, Cross W, et al. Motivational interviewing to explore culturally and linguistically diverse people’s comorbidity medication self-efficacy. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(9–10):1269–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12700.

O’Callaghan C, Quine S. How older Vietnamese Australian women manage their medicines. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2007;22(4):405–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-007-9045-3.

Alzayer R, Chaar B, Basheti I, et al. Asthma management experiences of Australians who are native Arabic speakers. J Asthma. 2018;55(7):801–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.1362702.

Alzubaidi H, Mc Mamara K, Chapman C, et al. Medicine-taking experiences and associated factors: comparison between Arabic-speaking and Caucasian English-speaking patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2015;32(12):1625–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12751.

Almansour H, Chaar B, Saini B. Perspectives and experiences of patients with type 2 diabetes observing the Ramadan fast. Ethn Health. 2016;23:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2016.1269156.

Ahmad A, Khan M, Aslani P. A Qualitative Study on Medication Taking Behaviour Among People With Diabetes in Australia. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.693748.

Bellamy K, Ostini R, Martini N, et al. Perspectives of resettled African refugees on accessing medicines and pharmacy services in Queensland, Australia. Int J Pharm Pract. 2017;25(5):358–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12324.

Mohammad A, Saini B, Chaar BB. Exploring culturally and linguistically diverse consumer needs in relation to medicines use and health information within the pharmacy setting. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11(4):545–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.11.002.

Clark A, Gilbert A, Rao D, et al. “Excuse me, do any of you ladies speak English?” Perspectives of refugee women living in South Australia: barriers to accessing primary health care and achieving the Quality Use of Medicines. Aust J Prim Health. 2014;20(1):92–7. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY11118.

Whittaker A, Lohm D, Lemoh C, et al. Investigating understandings of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in diverse ethnic communities in Australia: findings from a qualitative study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2019;8(3):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics8030135.

El Samman F, Chaar BB, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medicines and disease information needs of older Arabic-speaking Australians. Australas J Ageing. 2013;32(1):28–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00587.x.

Alzubaidi H, Marriott J. Patient involvement in social pharmacy research: Methodological insights from a project with Arabic-speaking immigrants. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(6):924–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.08.008.

Abdelmessih E, Simpson MD, Cox J, et al. Exploring the health care challenges and health care needs of arabic-speaking immigrants with cardiovascular disease in Australia. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019;7(4):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7040151.

Malhotra R, Bautista MAC, Tan NC, et al. Bilingual text with or without pictograms improves elderly Singaporeans’ understanding of prescription medication labels. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):378–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx169.

Shnaigat M, Downie S, Hosseinzadeh H. Effectiveness of health literacy interventions on COPD self-management outcomes in outpatient settings: a systematic review. COPD. 2021;18(3):367–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2021.1872061.

Culhane-Pera KA, Pergament SL, Kasouaher MY, et al. Diverse community leaders’ perspectives about quality primary healthcare and healthcare measurement: qualitative community-based participatory research. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01558-4.

Youssef J, Deane FP. Arabic-speaking religious leaders’ perceptions of the causes of mental illness and the use of medication for treatment. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47(11):1041–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867413499076.

Kirkpatrick CMJ, Roughead EE, Monteith GR, et al. Consumer involvement in quality use of medicines (QUM) projects – lessons from Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5(1):75. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-5-75.

Funding

No specific funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sawalha, R., Hosseinzadeh, H. & Bajorek, B. Culturally and linguistically diverse patients’ perspectives and experiences on medicines management in Australia: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm 45, 814–829 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01560-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01560-6