Abstract

Background Patients with chronic diseases exploit complementary and alternative treatment options to manage their conditions better and improve well-being. Objective To determine the prevalence and predictors of herbal medicine use among Type 2 Diabetes patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Setting Secondary healthcare facilities in Lagos state, Nigeria. Method The study design was a cross sectional survey. A two-stage sampling approach was used to select the health facilities and patients were recruited consecutively to attain the sample size. Data was collected using a structured and standardized interviewer-administered questionnaire. Characteristics, prevalence and predictors of herbal medicine use were assessed using descriptive statistics and multivariate regression analyses. Main outcome measure Herbal medicine use among Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Results 453 patients were surveyed, 305 (67.3%) reported herbal medicine use, among whom 108 (35.4%) used herbal and conventional medicines concurrently; 206 (67.5%) did not disclose use to their physician. Herbal medicine use was significantly associated with age (p = 0.045), educational level (p = 0.044), occupation (p = 0.013), duration of diabetes disease (p = 0.007), mode of diabetes management (p = 0.02), a positive history of diabetes (p = 0.011) and presence of diabetes complication (p = 0.033). Formulations or whole herbs of Vernonia amygdalina, Moringa oleifera, Ocimum gratissimum, Picralima nitida, and herbal mixtures were the commonest herbal medicine. Beliefs and perceptions about herbal medicine varied between the users and non-users. Conclusion The use of herbal medicine among Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Lagos, Nigeria is high. There is dire need for health care practitioners to frequently probe patients for herbal medicine use and be aware of their health behaviour and choices, with a view to manage the disease better.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on practice

-

Health care providers should make concerted efforts to identify herbal medicine use by patients in order to prevent potential adverse herb–drug interactions.

-

Herbal medicine effects and safety should be significantly incorporated in continuing education for clinical pharmacists so that they can confidently engage diabetic patients on such issues.

-

Clinical pharmacists should include herbal medicines and their effects in patient education and counselling.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) contributes significantly to the high mortality from non-communicable diseases worldwide [1]. Currently, about 6.4% of the global population have DM and this figure is expected to rise significantly by 2040. DM is an existential threat to the health of African populations with 14.2 million adults living with diabetes and estimated to double by 2040. Nigeria recorded 1.6 million cases of diabetes in 2015 making her the third highest ranking country for diabetic patients in Africa [2].

T2DM represents approximately 90–95% of all the three main types of diabetes—Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM), [3]. T2DM results from the interplay of hereditary, environmental and lifestyle factors, and it is associated with various micro- and macro- vascular complications which are the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the diabetic population [4]. The incidence of T2DM is rising progressively in many parts of Africa; and this has been attributed to higher obesity rates, sedentary lifestyle and rapid urbanization [5, 6]. The management of T2DM entails the use of insulin and hypoglycaemic medicines. Despite the development of newer classes of glucose-lowering agents, diabetes management still remains an ongoing challenge. Limited access to medicines, self-blood sugar monitoring tools, health care services, and good quality care hampers successful diabetes management in Africa. Consequently, the disease poses a high financial burden on the patients due to out-of-pocket payment for healthcare costs. This is heightened by the ineffective health insurance schemes operational in most African countries coupled with meagre government support for diabetes services [5, 7]. Owing to the chronic course of DM, the debilitation of complications, complexities of treatment plans and the exorbitant cost of medication and treatment services, diabetic patients recourse to complementary and alternative treatment options.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) involves a broad set of therapies and practices which are not considered part of a country’s conventional healthcare [8]. Herbal medicine (HM), an integral part of traditional medicine, is the most frequently used CAM in different parts of the world [9, 10]. There has been a renewed interest in herbal medicine evidenced by its increasingly widespread use in both developing and developed nations [8]. Reports of a national health interview in the United States showed that about 40.6 million adults used herbs and supplements in 2012 [11]. In Nigeria, the use of HM has been reported in the general population [12, 13] and various patient populations [14,15,16,17], with prevalence rates range of 24–83%. HM is particularly popular among patients with chronic diseases [10, 18], especially in developing nations where people depend extensively on herbal medicine as the primary source of healthcare [19, 20].

A previous study of DM patients in Lagos, Nigeria established CAM as an important element of DM management, with herbal medicine as the most prevalent form of CAM utilised [21]. However, the use of herbal medicine specifically in T2DM patients has not been studied. This study sought to ascertain the characteristics and level of herbal medicine use among T2DM patients in Lagos, Nigeria. The findings of this study have the potential to enhance health care providers’ awareness, improve patient education about herbal medicine, and inform further research openings into herbal medicine use and safety.

Aim of study

The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence, predictors, perceptions, and beliefs of herbal medicine use among T2DM patients registered in secondary healthcare facilities in Lagos state, Nigeria.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) Idi-araba Lagos, with approval number: ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/864. Approval was also obtained from the Lagos State Health Service Commission (HSC). The research did not pose any cost or risk to patients and their informed consent to participate in the study was obtained. Patients’ confidentiality was also maintained by not using their names and clinic record number on the data collection tool.

Methods

The study was a descriptive, cross-sectional survey of T2DM outpatients registered at five (5) secondary health care facilities (commonly called general hospitals) across Lagos State. The hospitals were selected using a two-stage stratified sampling design. Lagos State was ranked into five (5) strata based on its administrative divisions namely: Ikorodu, Badagry, Ikeja, Lagos Island and Epe. Ikeja and Lagos Island are metropolitan while Ikorodu, Badagry, and Epe are predominantly rural. One general hospital from each stratum was randomly selected for this study, which was carried out between September 2016 and February 2017. The inclusion criteria were: T2DM patients above 18 years and not pregnant, registered and managed at the different hospitals, and attending the Endocrinology clinic during the study period. Eligible subjects were consecutively recruited into the study on clinic days until the required study sample size was attained. The sample size was calculated using the formula:

where Z = statistic corresponding to 95% level of confidence = 1.96; P = expected prevalence obtained from same studies or a pilot study; d = margin of error or precision. Assuming a 46% prevalence (P) of herbal medicine use among diabetic patients [21], a 95% CI (Z = 1.96) and a prevalence estimate within 5% error margin (d), a minimum of 381 adults across the five study sites was considered appropriate for this study.

Data was collected using an adapted and modified interviewer-administered questionnaire, previously developed and validated on Complementary and Alternative Medicine use [22]. The study instrument had four domains namely: socio-demographic characteristics, diabetes-related characteristics, mode and characteristics of herbal medicine use, and attitudes and perceptions of herbal medicine use. A pilot study using 20 randomly selected T2DM patients attending the Endocrinology clinic of Lagos University Teaching Hospital was carried out to establish face validity. Reliability test of the instrument yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.750 and all the questions in the study instrument were deemed appropriate for the objectives of the study. Patients were interviewed by final year Pharmacy students trained in questionnaire administration and interviewing skills. Respondents who had used herbal medicine at any time since diagnosis of diabetes were taken as users while those who had never used herbal medicine were considered non-users. The respondents were approached while waiting to see the physician and briefed on the objectives of the study. Only patients who gave informed consent were interviewed.

The collected data were checked for completeness; responses were coded and analysed using IBM SPSS version 21.0 for Windows. Frequencies and percentages were used to assess the prevalence, types, mode and patterns of herbal medicine use. Student’s t test was used to test for differences in socio-demographic characteristics, perceptions and attitudes between users and non-users of herbal medicine. Association between patient characteristics and herbal medicine use was tested using Pearson’s Chi square. A multivariate logistic regression model with herbal medicine use as the dependent variable was employed to identify the predictors of herbal medicine use. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. A total of 453 T2DM patients were recruited from the five General Hospitals (GH) as follows: Isolo GH (120), Lagos Island GH (91), Ikorodu GH (120), Epe GH (67) and Badagry GH (60). This population had a mean age of 57.9 ± 14.6 years, 68.4% were females, and 74.4% were married. Majority of the participants (77.9%) had attained primary education at least, 35.5% were traders. Pearson Chi square test showed an association between the patients’ age and occupation with herbal medicine use.

The respondents had a mean disease duration of 5.7 ± 4.0 years and managed their disease both pharmacologically and non-pharmacologically. A positive family history of diabetes was reported by 189 (41.3%) respondents. The most prominent complications include: hypertension (47.7%), retinopathy (38.2%) and neuropathy (34.7%). Herbal medicine use was associated with: duration of diabetes (p = 0.001), disease management: diet (p = 0.001), exercise (p = 0.023), insulin (p = 0.044), and diabetes complication: retinopathy (p = 0.005), stroke (p = 0.022), neuropathy (p = 0.001), and nephropathy (p = 0.003) (Table 2).

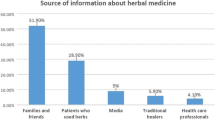

67.3% of the respondents used herbal medicine to control their blood glucose. 35.4% of these users consumed herbal and prescribed medicines concurrently, two hundred and six (67.5%) of them did not inform their physicians of using herbal medicine. Over half of the herbal medicine users (55.1%) used herbal medicine also for other ailments, especially feverish conditions (17.7%). Their perceived reasons for using herbal medicine ranged from better efficacy than orthodox medicines (27.4%) to safety of herbal medicines (49.7%). Response by the users showed that friends (33.8%) were the main sources of recommendation to use herbal medicine (Table 3).

Multiple regression analysis showed the following as predictors of herbal medicine use: older age, educational level, longer disease duration, diabetes management using diet, oral hypoglycaemics, and insulin, a positive family history of diabetes and having neuropathy (Table 4).

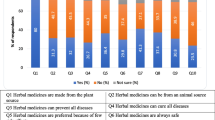

Majority of the respondents expressed no opinion on their beliefs about herbal medicine. Among those who responded, the users believed herbal medicines are safe, beneficial and more effective than orthodox medicines for some illnesses while the non-users believed that the herbal medicine use is dangerous and should be disclosed to the physicians (Fig. 1a, b). Attitudes and beliefs about herbal medicine differed between the users and non-users (p < 0.05).

The most frequently used herbal medicines reported by our respondents were: Vernonia amygdalina leaves (13.1%), Moringa oleifera seeds (10.2%), Herbal mixtures (7.9%), Ocimum gratissimum leaves (6.9%), Agbo iba (a local herbal mixture—6.6%) and Picralima nitida seeds (4.6%) (Fig. 2). These herbal medicines are administered in different ways such as infusions, decoctions or tinctures.

Discussion

Patients with chronic diseases continuously seek complementary and alternative ways to manage their disease conditions and improve their health. The use of herbal medicine is fast assuming an important role in the management of T2DM.

The prevalence of herbal medicine use in our study population was 67.3%. Reports from similar studies locally and globally showed varied prevalence. A lower prevalence (46%) was reported for CAM use among diabetic patients in Nigeria [21], suggesting increased use of herbal medicine by diabetic patients over the years. Similar studies in North Sudan and Saudi Arabia showed the prevalence of herbal medicine use in T2DM patients to be 52% [23] and 25.8% [24] respectively. Lower prevalence rates were also reported for diabetic patients in Kenya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Guinea [7, 18, 20, 25]. In other studies, CAM use in diabetic and T2DM patients was investigated and the prevalence rates ranged from 61 to 76% [26,27,28,29,30]. In these studies, herbal medicine was the most commonly reported CAM type. This disparate prevalence rates could be adduced to differences in the study settings, geographical location, and levels of the population’s dependence on herbal remedies. Regardless of this differing prevalence of herbal medicine use in diabetic patients, herbal medicine is evidently an important feature of diabetes management worldwide. In our study population, 35.4% of users concurrently consumed herbal and prescribed medicines; same behaviour has been reported amongst diabetic patients in other studies [20, 26, 31] and with other disease conditions [32]. In a previous study from Nigeria, diabetic patients adhered to their prescribed orthodox medicines despite the use of CAM [21]. Concurrent use of herbal and orthodox medicines increases patients’ risk of herb–drug interactions (HDIs). HDIs can result in potentially severe adverse effects or reduced benefits from prescribed medicines [33]. Most medicinal plants of African origin lack safety and pharmacokinetic information which can be used to prevent potentially clinically relevant HDIs [34]. The effects of such HDIs especially in the milieu of a deficient health care system in many developing nations can be deleterious to patients and the society at large.

Vernonia amygdalina leaves, Moringa oleifera seeds, Ocimum gratissimum leaves, herbal mixtures and Picralima nitida seeds were the herbal medicines most frequently used by our respondents (Fig. 2). These herbal medicines are house-hold regulars in the traditional treatment of diabetes in Nigeria [35,36,37,38]. Although the hypoglycaemic activity of these plants has been established in animals as well as humans [39,40,41,42,43,44], thus supporting their traditional use in DM treatment, there is paucity of data on their interactions with orthodox medicines. Cocktail of various medicinal plants is often used for synergistic effect, and by extension, elevating the risks for herb–herb interactions.

The result from this study is consistent with a similar study [45], in which the most widely reported reason for HM use was its perceived safety (Table 3). In Nigeria and most African countries, herbal medicines are generally perceived and widely advertised as being devoid of any side effects because they are “natural”. However, clinical reports of several HDIs have shown this belief to be erroneous. Few examples include the interaction of Matricaria recutita (Chamomile) with warfarin resulting in over-coagulation; Allium sativum (Garlic) altered the pharmacokinetics of paracetamol and caused hypoglycaemia when co-administered with chlorpropamide [33]. Less than fifty percent of the herbal medicine users notified their physician of their use. Studies in Saudi Arabia and Jordan also reported this practice [7, 46, 47]. We did not seek to know the patients’ reasons for withholding such vital information; nonetheless, previous similar reports suggest that patients are either not asked by their physicians or do not trust them enough to reveal HM use to them. Western-trained physicians also often have limited knowledge of herbal medicine effects and may not confidently discuss this with their patients [23].

The predictors of herbal medicine use from our study are age, educational level, occupation, a longer duration of diabetes, mode of diabetes management, a positive family history of diabetes and diabetes complication (neuropathy) (Table 4). Increasing age has been reported to be associated with alternative medicine use in diabetic patients [21, 23, 48, 49]. This can be explained by the presence of multiple disease states and co-morbidities in the elderly and the consequent desire to seek various treatment options to be in better control of their health condition. Educational level positively influenced herbal medicine use in our respondents, contrary to findings from Alami et al. [18]. This may reflect better knowledge and awareness of herbal medicine due to higher literacy rates among those with formal education. Our results also support previous reports on the association of a longer duration of diabetes with herbal medicine use [23]. However, patients with longer diabetes disease duration do not necessarily use herbal medicine as observed by Huri et al. [49]. The presence of a diabetic complication shows the severity of diabetes disease and increased need for more treatment alternatives. Management of diabetes using diet, insulin and oral hypoglycaemic medicines was significantly associated with HM use. Patients using oral hypoglycaemic agents were more likely to use HM compared to those on insulin and diet respectively. This could be due to the high cost of hypoglycaemic medicines as was seen in diabetic patients in North Sudan who used herbs specifically because of conventional treatments costs [23].

On the perceptions and beliefs concerning HM, relative to the non-users, users believed HM to be efficacious, beneficial and safe (Fig. 1), similar to findings in Saudi Arabia [45]. This resonates with the general belief that herbal remedies are natural and therefore, risk-free. These beliefs could also be culturally rooted [50]. The non-users on the other hand, believed it is risky to use herbal and orthodox medicines concurrently and such use should be disclosed to physicians, which is a possible explanation of why they do not indulge in HM use.

Our study has a broad patient coverage and specificity. Herbal medicine use, being the most prevalent form of CAM was assessed in contrast to the more general CAM use which has been previously reported. The burden of diabetes globally is attributed to T2DM; therefore, this study examined T2DM patients. The limitations of this study include the following: (1) only patients who attended hospitals were surveyed, (2) individuals who are either undiagnosed or patients who received care outside the hospital were not accounted for, (3) private health facilities were not included in our study, (4) there was no inquiry of the identity and number of prescribed medications used by the respondents because it was not part of the objectives of the study. These limitations however, do not in any way alter our findings.

Conclusion

Prevalence of 67.3% was obtained for HM use among Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Over a quarter of these patients used herbal medicine concurrently with prescribed medications, thus increasing the potential for herb–drug interactions and consequently, therapy failure. Further research into the pharmacokinetics of herbal medicines should be carried out to enable prediction and identification of potential clinically relevant herb–drug interactions in diabetic patients. Health care providers, particularly, physicians and pharmacists, should routinely inquire and discuss herbal medicine use with patients in a very caring and unbiased manner.

References

World Health Organisation. WHO global status report on non-communicable diseases 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 06 Nov 2017.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn. Brussels, Belsium: IDF, 2015. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/resources/2015-atlas.html. Accessed 21 Oct 2017.

Alebiosu OC, Familoni OB, Ogunsemi OO, Raimi TH, Balogun WO, Odusan O, et al. Community based diabetes risk assessment in Ogun state, Nigeria (World Diabetes Foundation Project 08-321). Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(4):653–8.

Olokoba AB, Obateru OA, Olokoba LB. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of current trends. Oman Med J. 2012;27(4):269–73.

Mbanya JC, Assah FK, Saji J, Atanga EN. Obesity and Type 2 diabetes mellitus in sub-Sahara Africa. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:501.

Idemyor V. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: health care perspectives, challenges and the economic burden of disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(7):650–3.

Algothamy AS, Alruqayb WS, Abdallah MA, Mohamed KM, Albarraq AA. Prevalence of using herbal drugs as anti-diabetic agents in Taif Area, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Health Sci. 2016;3(3):137–40.

World Health Organisation. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy: 2014-2023. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_eng.pdf. Accessed 20 Mar 2017.

Leach MJ, Lauche R, Zhang AL, Cramer H, Adams J, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Characteristics of herbal medicine users among internal medicine patinets: a crosss-sectional analysis. J Herb Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hermed.2017.06.005.

Tulunay M, Aypak C, Yikilkan H, Gorpelioglu S. Herbal medicine use among patients with chronic diseases. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol. 2015;4(3):217–20.

Wu C, Wang C, Tsai M, Huang W, Kennedy J. Trend and pattern of herb and supplement use in the United States: results from the 2007 and 2012 National health interview surveys. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/872320.

Oreagba IA, Oshikoya KA, Amachree M. Herbal medicine use among urban residents in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-11-117.

Awodele O, Amagon KI, Usman SO, Obasi PC. Safety of herbal medicines use: case study of Ikorodu residents in Lagos, Nigeria. Curr Drug Saf. 2014;9:138–44.

Achigbu EO, Achigbu KI. Traditional medication use among out-patients attending the eye clinic of a Secondary health facility in Owerri South-East Nigeria. Orient J Med. 2014;62(3–4):107–13.

Onyeka TC, Ezike HA, Nwoke OM, Onyia EA, Onuorah EC, Anya SU, Nnacheta TA. Herbal medicine: a survey of use in Nigerian presurgical patients booked for ambulatory anaesthesia. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012; 12:30. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/12/130.

Nwako OS, Fakeye TO. Evaluation of use of herbal medicines among ambulatory hypertensive patients attending a Secondary healthcare facility in Nigeria. Int J Pharm Pract. 2009;17(2):101–5.

Fakeye TO, Adisa R, Ismail ME. Attitude and use of herbal medicines among pregnant women in Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-9-53.

Alami Z, Aynaou H, Alami B, Hdidou Y, Latrech H. Herbal medicines use among diabetic patients in Oriental Morocco. J Pharmacogn Phyther. 2015;7(2):9–17.

Jegede A, Oladosu P, Ameh S, Kolo I, Izebe K, Builders P, et al. Status of management of diabetes mellitus by traditional medicine practitioners in Nigeria. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5(27):6309–15.

Mwangi J, Gitonga L. Perceptions and use of herbal remedies among patients with diabetes mellitus in Murang’a North District, Kenya. Open J Clin Diagn. 2014;4:152–72.

Ogbera A, Dada O, Adeleye F, Jewo P. Complementary and alternative medicine use in diabetes mellitus. West Afr J Med. 2010;29(3):158–61.

Quandt SA, Verhoef MJ, Arcury TA, Lewith GT, Steinsbekk A, Kristoffersen AE, et al. Development of an international questionnaire to measure use of complementary and alternative medicine (I-CAM-Q). J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(4):331–9.

Ali BAM, Mohamed MS. Herbal medicine use among patients with Type 2 diabetes in North Sudan. Annu Res Rev Biol. 2014;4(11):1827–38.

Al-garni AM, Al-Raddadi RM, Al-Amri TA. Patterns and determinants of complementary and alternative medicine use among Type 2 diabetic patients in a diabetic center in Saudi Arabia. J Fundam Appl Sci. 2017;19(1S):1738–48.

Baldé NM, Youla A, Baldé MD, Kaké A, Diallo MM, Baldé MA, Maugendre D. Herbal medicine and treatment of diabetes in Africa: an example from Guinea. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32(2):171–5.

Chang HA, Wallis M, Tiralongo E. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among people with Type 2 diabetes in Taiwan: a Cross-sectional survey. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/983792.

Ching SM, Zakaria ZA, Paimin F, Jalalian M. Complementary alternative medicine use among patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in the primary care setting : a cross-sectional study in. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:148. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-13-148.

Medagama AB, Bandara R, Abeysekera RA, Imbulpitiya B, Pushpakumari T. Use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) among type 2 diabetes patients in Sri Lanka: a cross sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014; 14:374. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/14/374.

Bell RA, Suerken CK, Grzwacz JG, Lang W, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults with diabetes in the United States. Altern Ther Health Med. 2006;12(5):16–22.

Khalaf AJ, Whitford DL. The use of complementary and alternative medicines by patients with diabetes mellitus in Bahrain: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Atern Med. 2010;10:35. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/10/35.

Singh J, Singh R, Gautam CS. Self-medication with herbal remedies amongst patients of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a preliminary study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(4):662–3.

Tarirai C, Viljoen AM, Hamman JH. Herb–drug interactions reviewed. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6(12):1515–38.

Izzo AA. Interactions between herbs and conventional drugs: overview of the clinical data. Med Princ Pract. 2012;21(5):404–28.

Ezuruike UF, Prieto JM. The use of plants in the traditional management of diabetes in Nigeria: pharmacological and toxicological considerations. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155(2):857–924.

Borokini TI, Ighere DA, Clement M, Ajiboye TO, Alowonle AA. Ethnobiological survey of traditional medicine practice for the treatment of piles and diabetes mellitus in Oyo State. J Med Plants Stud. 2013;1:30–40.

Arowosegbe S, Olanipekun MK, Kayode J. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes mellitus in Ekiti Souh Senatorial District, Nigeria. Eur J Bot Plant Sci Phytol. 2015;2(4):1–8.

Kadiri M, Ojewumi AW, Agboola DAAM. Research article ethnobotanical survey of plants used in the management of diabetes mellitus in Abeokuta, Nigeria. J drug Deliv Ther. 2015;5(3):13–23.

Ofuegbe SO, Adedapo AA. Ethnomedicinal survey of some plants used for the treatment of diabetes in Ibadan, Nigeria. Asian J Med Sci. 2015;6(5):36–40.

Chikezie PC, Ojiako OA, Nwufo KO. Overview of anti-diabetic medicinal plants: the Nigerian research experience. J Diabetes Metab. 2015;6:546. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6156.1000546.

Okolie UV, Okeke CE, Oli JM, Ehiemere IO. Hypoglycaemic indices of Vernonia amygdalina on postprandial blood glucose concentration of healthy humans. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7(24):4581–5.

Oguanobi NI, Paschal Chijioke C, Ghasi S. Anti-diabetic effect of crude leaf extracts of ocimum gratissimum in neonatal streptozotocin-induced type-2 model diabetic rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;4(Suppl 5):77–83.

Ezeigbo OR, Barrah CS, Ezeigbo IC. Phytochemical Analysis and antidiabetic effect of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Moringa oleifera leaves in alloxan-induced diabetic wistar albino rats using insulin as reference drug. Int J Diabetes Res. 2016;5(3):48–53.

Hussain SS, Khalid HE, Ahmed SM, Technologies A. Anti-diabetic activity of the leaves of Moringa oleifera Lam. growing in Sudan on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Br J Med Heal Res. 2016;3(4):48–57.

Aguwa CN, Ukwe CV, Inya-Agha SI, Okonta JM. Antidiabetic effect of picralima nitida aqueous seed extract in experimental rabbit model. J Nat Remedies. 2001;1(2):135–9.

Suleiman KA. Attitudes and beliefs of consumers of herbal medicines in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Community Med Health Educ. 2013;4(2):2–7.

Al-Rowais NA. Herbal medicine in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:1237–41.

Wazaify M, Afifi FU, El-Khateeb M, Ajlouni K. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Jordanian patients with diabetes. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):71–5.

Egede LE, Ye X, Zheng D, Silverstein MD. The prevalence and pattern of complementary and alternative medicine use in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):324–9.

Huri HZ, Lian GTP, Hussain S, Pendek S, Widodo RT. A survey amongst complementary and alternative medicine users with Type 2 diabetes. Int J Diabetes Metab. 2009;17:9–15.

Arcury TA, Bell RA, Snively BM, Smith SL, Skelly AH, Wetmore LK, Quandt SA. Complementary and alternative medicine use as health self-management: rural older adults with diabetes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:S62–70.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate all the patients who took part in this study. We also thank the administrative staff and nurses in the five health facilities that assisted in maintaining orderliness with the respondents during the interviews.

Funding

The research was funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amaeze, O.U., Aderemi-Williams, R.I., Ayo-Vaughan, M.A. et al. Herbal medicine use among Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Nigeria: understanding the magnitude and predictors of use. Int J Clin Pharm 40, 580–588 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0648-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0648-2