Abstract

Background While evidence on implementation of medication safety strategies is increasing, reasons for selecting and relinquishing distinct strategies and details on implementation are typically not shared in published literature. Objective We aimed to collect and structure expert information resulting from implementing medication safety strategies to provide advice for decision-makers. Setting Medication safety experts with clinical expertise from thirteen hospitals throughout twelve European and North American countries shared their experience in workshop meetings, on-site-visits and remote structured interviews. Methods We performed an expert-based, in-depth assessment of implementation of best-practice strategies to improve drug prescribing and drug administration. Main outcome measures Workflow, variability and recommended medication safety strategies in drug prescribing and drug administration processes. Results According to the experts, institutions chose strategies that targeted process steps known to be particularly error-prone in the respective setting. Often, the selection was channeled by local constraints such as the e-health equipment and critically modulated by national context factors. In our study, the experts favored electronic prescribing with clinical decision support and medication reconciliation as most promising interventions. They agreed that self-assessment and introduction of medication safety boards were crucial to satisfy the setting-specific differences and foster successful implementation. Conclusion While general evidence for implementation of strategies to improve medication safety exists, successful selection and adaptation of a distinct strategy requires a thorough knowledge of the institute-specific constraints and an ongoing monitoring and adjustment of the implemented measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts of findings

-

Instead of consecutively adapting a list of best-practice strategies, institutions aiming at implementing a safety strategy should assess their medication processes and errors for risk before selecting a strategy.

-

A liable, multidisciplinary team should be set in place that both triggers and monitors the implementation of safety strategies.

-

More than one strategy targeting the same problem may be implemented at different wards in one institution, particularly to safeguard drug administration.

Introduction

It is well known that drug treatment is a risky endeavor [1] and, therefore, health care professionals, institutions, and even entire countries have developed strategies to improve medication safety. As a result, there is a rapidly increasing body of literature on quality improvement strategies and error prevention techniques. Unfortunately, many of these are not comparable due to a variation in the definitions of strategies used or the outcome variables measured [2]. Moreover, the transferability and generalizability of a singular improvement strategy to a different setting appears low; identical interventions that have worked well in one setting have failed in another [3, 4]. Interventions to improve safety are often complex and rarely target a single process. They are much more likely to target an intertwined workflow that depends on the collaboration of numerous health care professionals [5]. A decisive factor for the success of complex interventions is their implementation period which includes the adaptation of a tool to the individual setting [6, 7]. For example, the failure of a safety intervention such as electronic prescribing could be related to poor implementation [8], the use of a poorly working system [9], or the fact that electronic prescribing alone will never improve the overall treatment process. The implementation phase of an intervention is rarely described in detail in published studies, which mainly focus on outcomes. Therefore, knowledge on why one safety intervention was favored above other strategies in the first place, and how it was subsequently adapted and shaped to fit a specific setting is not disseminated and tends to remain local site knowledge. Likewise, most internationally renowned recommendations on preferential implementation of medication safety strategies rely on expert consensus [10–12] and, again, generally these recommendations do not reflect the train of thoughts that led the experts to their conclusions. This study invited colleagues to join an expert group and share relevant events and experiences, critical steps, and challenges they encountered in their institutions while implementing strategies to safeguard drug prescribing and drug administration. We compiled and jointly communicated details of such implementation processes that were perceived relevant in retrospect for success or failure of a particular intervention.

Aim of the study

The purpose of this assessment was to gather and structure knowledge in order to support other health care professionals, institutions, and policy makers in their decision-making process which medication safety strategies could be adopted in a specific institution. We further aimed at collecting information on context factors that might foster or hinder a successful implementation.

Ethical approval

This qualitative study reports data gathered from expert group discussions, personal interviews, and questionnaires. All interactions were open thus revealing identity of the respondent and the affiliated institution. The participating experts agreed on the study goals and the publication and all are listed either as authors or mentioned in the acknowledgement section. Therefore, no ethical approval was deemed necessary.

Methods

The study was put out to tender by the German Ministry of Health as research project analyzing the medication process and the potential impact of medication safety strategies in five countries.

The assessment focused on medication safety strategies tailored to the prescribing and/or administration process as these are considered the two most error prone steps during inpatient care [13].

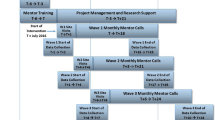

From May till November 2012, we conducted an open, prospective, qualitative assessment with international experts from European and non-European countries. Thereby, experts participated either in the core project team (N = 10, Table 1) or as consultant experts (N = 10, Table 2). Experts from the core project team represented five institutions from five European countries (Table 1). They participated in a group meeting and a final workshop in Heidelberg, Germany and provided an on-site-visit for the Heidelberg project team in their respective institutions. Experts were preselected based on their expertise in medication safety, their publication record in the field, and international visibility. Moreover, they should work in a hospital setting to have insight into actual medication processes and experience in implementing medication safety strategies. Subsequently they were invited to participate in the project and asked whether they have been deeply involved in leading the deployment of medication safety improvement actions. If so, they needed to be willing to share in-depth knowledge and personal experience with successful and failed medication safety strategies to qualify as participant.

The first group meeting was held as a 1-day workshop in Heidelberg with experts from the core project team. The aim of this meeting was to (1) collect information on the processes of drug prescribing and drug administration in the individual institutions in order to (2) define a generic process description for the prescribing and administration process that allowed to (3) identify error-prone sub-steps of both processes and facilitated (4) a comparison of data from different institutions with regard to their peculiarities. As a flexible tool to structure the processes we applied Ishikawa diagrams [14]. While Ishikawa diagrams are typically used to analyze cause and effect of a certain event, we choose their structure to display the respective drug treatment processes with their pertinent sub-processes following a chronological order. Hence, an error-free process would presume error-free sub-processes as well and thereby, the Ishikawa diagrams helped to identify error-prone sub-steps and also to align reported strategies to improve medication safety to a specific step in the process (Fig. 1a, b). Results from expert group discussions with the core group were documented during the discussions on flipcharts and posters. Therefore, the key findings were immediately collected, shared with the team, and discussed and clarified if necessary. Therefore, no audiotaping or videotaping was conducted.

In preparation of the on-site visits, experts were asked to specify medication safety strategies that were implemented in their institution to safeguard a specific sub-step via a paper-based survey. During the on-site visits at the expert’s local institution, described medication safety strategies were discussed with regard to selection criteria and reasons why one specific strategy was chosen over another one. On-site visits were documented on predefined documentation sheets by a Heidelberg study team member. After the visits, the handwritten notes were transferred to electronic format and send via email to the respective expert for double check and verification.

After termination of the on-sites visit, consultant experts from additional European countries as well as from the US, Canada, and Australia as international reference countries were invited via email to participate. Ten experts from eight additional institutions in Austria, Denmark, Norway, Spain, and Sweden as well as from the US and Canada followed the invitation (Table 2). After instruction via email and phone they were asked to fill in the documentation material with regard to their institution. This included the specification of the drug prescribing and administration process alongside the Ishikawa diagrams, identification of error-prone sub-steps and description of implemented medication safety strategies. The information provided in the semi-structured questionnaire survey among the consultant experts was analysed by two members of the Heidelberg study team and uncertainties or ambiguities were clarified with the expert abroad.

In order to correlate implementation medication safety strategies with local and national constraints, all international experts involved in the study were asked to complete a questionnaire on locally and nationally available context factors that might impact the selection and implementation of medication safety strategies. Again, this questionnaire was read by two members of the Heidelberg study team and uncertainties or ambiguities were clarified with the expert abroad.

A final workshop with the core expert team and additional invited national experts and decision-makers from Germany was held in Heidelberg to discuss the aggregated results from each institution also with regard to potential applicability for the German health care system. Subsequently, experts should rank the suggested medication safety strategies considering the needed resources, the effort of implementation, the potential acceptance of the strategy and the benefit for medication and patient safety to adapt a list of recommended best-practice strategies both on a national and institutional level.

Results

Implemented medication safety strategies

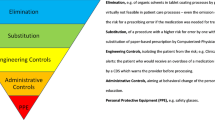

During the expert discussions it became evident that interventions of the same nomenclature actually varied largely in how they were understood and carried out in different institutions. Hence, in order to harmonize the discussion and introduce a common denominator, we introduced a glossary with strategies mentioned during the assessment and added a short description that was used throughout the project (Table 3). Across the 13 institutions, 13 different main medication safety strategies were implemented alone or in combination (Table 4). Interventions targeting drug prescribing were concordant in most institutions and focused on the implementation of electronic prescribing systems, medication reconciliation, and medication review; whereas strategies to safeguard the administration process appeared to be more heterogeneous. In some institutions, multiple differing strategies ensuring safe drug administration, e.g. patient trolleys and satellite pharmacies, were implemented on different wards taking into account the individual structure of the respective setting. Elaboration of medication safety strategies was linked with the local facilities (e.g. staff infrastructure). This highlighted the importance of being able to tailor strategies to individual settings to help eliminate or minimize local drawbacks (Tables 5, 6).

Selection and relinquishment of strategies: influence of error-prone sub-steps

The selection of strategies depended on particular sub-steps that were locally identified or perceived as error-prone. Indeed, we could identify several sub-steps both in drug prescribing and in drug administration that were congruently described as error-prone by the experts (Fig. 2). However, the experts found it challenging to reflect on processes when distinct medication safety strategies were already set in place for a long time and have become routine care.

a Most frequently mentioned errors occurring in at least six out of 12 institutions during drug prescribing highlighted in black. The US hospital is not included in this list because best practice strategies were set in place for so long that none of these steps were perceived error-prone anymore. b Most frequently mentioned errors occurring in at least six out of 12 institutions during drug administration highlighted in black. The US hospital is not included in this list because best practice strategies were set in place for so long that none of these steps were perceived error-prone anymore

With regard to drug prescribing, the majority of experts rated the interfaces of care as particularly error-prone in their institutions and concluded that consequent implementation of medication reconciliation helped to reduce errors of omission and documentation. During in-hospital care, transparency and information exchange was facilitated by the implementation of electronic prescribing systems, however, many of these systems were not fully linked to primary care and as a result, medication reconciliation at the interface of care was still deemed necessary. With regard to drug administration, application of parenteral drugs was generally perceived as more challenging than application of oral drugs. This led to the implementation of targeted measures such as the requirement for a double check during the preparation and application of all parenteral drugs. The sub-steps of actual application (i.e. risk of omission) as well as documentation were perceived as error-prone both for parenteral and for oral drugs. However, experts reflected that errors in these sub-steps could be often prevented by implementation of electronic prescribing systems with integrated medication administration records and did not require an additional, stand-alone intervention solely on the level of drug administration. To reduce prevalent errors in drug dispensing in preparation of drug administration, strategies were selected depending on the patient population, staff resources, and the prescribing pattern on the wards, and included bed-side cabinets, satellite pharmacies or unit-dose systems.

Selection and relinquishment of strategies: influence of context factors

Moreover, we learned that local context factors did substantially determine both the level of activity in different institutions regarding medication safety as well as the selection of distinct strategies. We identified two major types of context factors driving the decision process, namely the overall commitment to a medication safety culture and the available technical equipment including the information technology infrastructure of an individual institution. In our selection of institutions, nine of the 13 sites used hospital-wide electronic prescribing, three institutions were currently implementing an electronic prescribing system, and only one institution had neither planned to nor implemented electronic prescribing. Four out of the nine systems in use were homegrown, and in five institutions prescription was carried out bedside with mobile devices. Six out of nine systems supported mainly a prescription based on active ingredients instead of brands. In particular with regard to the implementation of simple checking for spelling and plausibility versus the integration of clinical decision support, the systems varied considerably in their functionalities and five systems offered at least simple plausibility checks. In all institutions, electronic prescribing systems were perceived as a vehicle for implementation of further medication safety strategies and as a necessary support tool to continuously monitor prescribing quality. Indeed, seven systems were explicitly used as platform to support medication review by documenting pharmacist recommendations.

Commitment to and awareness of medication safety was rated high in 12 of the institutions, and many offered incentives for medication safety programs (N = 11/13). Moreover, 11 institutions encouraged a lively communication of medication safety aspects with one influential person or committee being particularly responsible for medication safety (N = 10). Medication safety specific training was offered in 11 institutions. The experts reported that the awareness of medication safety and the existing communication and collaboration within and between professions facilitated the implementation and subsequent enhancement of medication safety strategies. According to the experts, further influential factors for the implementation of safety strategies were regional or national programs and the immediate linkage of medication safety programs with incentives. This was particularly evident for two of the strategies: electronic prescribing and medication reconciliation. All institutions with electronic prescribing had a nationally enforced recommendation for implementation and of the ten institutions performing medication reconciliation, eight were triggered or supported by a corresponding national guideline or program for medication reconciliation. In contrast, for the two institutions without a standardized medication reconciliation process, there was no national program in place. Hence, supportive structures on a national level were identified as particularly important to foster the implementation of cost- and labor-intensive strategies that bear a financial risk for the implementing institution.

Discussion

This qualitative expert anthology suggests help to understand the relationship of (successful) implementation of medication safety strategies with local institutional and national conditions. Overall, 20 experts working at 13 institutions in 12 countries shared their experience and thoughts on the successful implementation of strategies to enhance and promote medication safety during drug prescribing and drug administration. The discussion underlined the importance of an institution-wide awareness and commitment for medication safety with a strong clinically driven leadership. Only then—in a climate of change [15]—medication safety projects may prosper beyond time-limited pilot projects. Indeed, a leadership facilitating and supporting a safety climate in an institution might foster quality improvement initiatives which again may translate into patient safety [16]. As safety climate was also identified as an independent predictor for patient safety, it is even more important to work on the overall safety climate of an institution in addition to introduction of specific quality improvement strategies [16]. Internal [17] and external benchmarking [18] might help to support a longitudinal improvement. Especially for external benchmarking, self-assessment tools can be used, such as Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) used at the University Hospital in Geneva [19]. These are available in a standardized version, e.g. by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices [20], or adapted in a country-specific manner [21]. The experts confirmed that just debating and working on those assessment tools might help to form interdisciplinary medication safety teams and to objectively reflect the current (and past) situation of a specific institution. This is even more important when considering how crucially the history and background of an individual institution contributes to the selection and ongoing development of distinct medication safety strategies. As for the institutions in this assessment, hospitals usually started a process of change with one major process-modifying strategy such as electronic prescribing or unit-dose dispensing. Indeed, the implementation of such technical tools might enforce also workflow changes. Based on step-wise adaptation and integration of new features, the workflow was gradually and steadily improved, often taking many years to successfully close the gaps between electronic drug prescribing, dispensing, and drug administration [22]. A long lasting implementation phase requires a defined responsible person or team that advances and pushes the progress, as well as a sustained support from the organization. Often, these teams are not only involved at a higher process level, but also at an operational level, and can thus be concerned with the development, implementation, roll-out and monitoring of the technical tools.

The current assessment and methodology has several limitations to consider. First of all, we invited a limited number of experts on medication safety to participate in this survey—obviously this assessment bears the known weaknesses of any expert-based, subjective methodology with a high selection bias and may not offer a comprehensive, literature-based review of the topic. Nevertheless, we intentionally initiated an expert-based discourse gathering information-rich cases that should be able to provide the greatest insight into the topic [23]. In our set of experts, many clinical pharmacists were involved and discussions could become even more diverse the more different professions are asked. Interestingly, many institutions in this study had implemented technical solutions to foster medication safety, however, also social or leadership aspects can successfully support medication safety. Secondly, data acquisition was performed on-site with the core project team and only remotely with consultant experts. This might have resulted in a reporting bias if questions were misunderstood. We aimed to minimize this error by offering an intense telephone support and verified all statements of all experts in iterative feedback rounds. Lastly, terminology in the field of medication safety remains challenging [2, 24] and there are few generally accepted definitions of the strategies used. We therefore introduced a glossary (Table 3) and spent a reasonable amount of time to minimize these differences in our groups of experts—at least during discussions. However, it is evident that even if a congruent understanding of a medication safety strategy is found, its elaboration and adaptation to the specific context still varies.

Conclusion

Out of the growing number of (recommended) medication safety strategies, our expert opinion pool favored electronic prescribing with clinical decision support and medication reconciliation as the most promising and basic interventions. However, it became evident that successful implementation of any strategy requires thorough assessment of the local processes, constraints and opportunities in order to prioritize and measure different strategies and elaborate their distinct way of implementation. Therefore the foundation of a locally responsible, multiprofessional medication safety team was strongly recommended. National regulations helped to foster the implementation of a distinct strategy on a regional or national level but were seldom the trigger for unique milestone projects.

References

Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M, editors. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. To err is human—building a safer health care system. Washington: National Academies Press; 1999.

Lisby M, Nielsen LP, Brock B, Mainz J. How are medication errors defined? A systematic literature review of definitions and characteristics. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:507–18.

Aarts J, Berg M. A tale of two hospitals: a sociotechnical appraisal of the introduction of computerized physician order entry in two Dutch hospitals. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2004;107(Pt 2):999–1002.

Greengold NL, Shane R, Schneider P, Flynn E, Elashoff J, Hoying CL, et al. The impact of dedicated medication nurses on the medication administration error rate: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2359–67.

Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM, Taylor SL, Dy SM, Foy R, et al. Advancing the science of patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:693–6.

Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330:765.

Sittig DF, Stead WW. Computer-based physician order entry: the state of the art. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1:108–23.

Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, Clark RS, Watson RS, Nguyen TC, et al. Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1506–12.

Peikari HR, Zakaria MS, Yasin NM, Shah MH, Elhissi A. Role of computerized physician order entry usability in the reduction of prescribing errors. Healthc Inform Res. 2013;19:93–101.

Institute of Medicine: Consensus Report: Preventing Medication Errors. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2006/Preventing-Medication-Errors-Quality-Chasm-Series.aspx. Last Accessed 7 Sept 2015.

Agency for Healthcare Research. Making Health Care Safer II. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/services/quality/ptsafetyII-full.pdf. Last Accessed 7 Sept 2015.

National Quality Forum (NQF). Safe practices for better healthcare—2010 update: a consensus report. Washington: NQF; 2010.

Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Cooper J, Demonaco HJ, Gallivan T, et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events: ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1995;274:35–43.

Ishikawa K. Introduction to quality control. 3rd ed. New York: Quality Resources; 1990.

Benn J, Burnett S, Parand A, Pinto A, Vincent C. Factors predicting change in hospital safety climate and capability in a multi-site patient safety collaborative: a longitudinal survey study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:559–68.

McFadden KL, Stock GN, Gowen CR 3rd. Leadership, safety climate, and continuous quality improvement: impact on process quality and patient safety. J Nurs Adm. 2014;44:S27–37.

Redwood S, Ngwenya NB, Hodson J, Ferner RE, Coleman JJ. Effects of a computerized feedback intervention on safety performance by junior doctors: results from a randomized mixed method study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:63.

Padilla-Marín V, Corral-Baena S, Domínguez-Guerrero F, Santos-Rubio MD, Santana-López V, Moreno-Campoy E. ISMP-Spain questionnaire and strategy for improving good medication practices in the Andalusian health system. Farm Hosp. 2012;36:374–84.

Bonnabry P, Despont-Gros C, Grauser D, Casez P, Despond M, Pugin D, et al. A risk analysis method to evaluate the impact of a computerized provider order entry system on patient safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:453–60.

ISMP® Medication Self Assessment® for Hospitals. http://www.ismp.org/survey/default.asp. Last Accessed 7 Sept 2015.

French Agency for Hospitals’ performance (ANAP). Tool—assessment and management of risks related to medication process. http://www.anap.fr/publications-et-outils/outils/detail/actualites/evaluer-et-gerer-les-risques-lies-a-la-prise-en-charge-medicamenteuse-en-etablissement-de-sante-1/. Last Accessed 7 Sept 2015.

Poon EG, Keohane CA, Yoon CS, Ditmore M, Bane A, Levtzion-Korach O, et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1698–707.

Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990.

Pintor-Mármol A, Baena MI, Fajardo PC, Sabater-Hernández D, Sáez-Benito L, García-Cárdenas MV, et al. Terms used in patient safety related to medication: a literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:799–809.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participating experts and their respective institutions for their greatly appreciated support and efforts in this assessment, particularly the consultant experts (Blanca Argüello, Hospital de Leon, Leon, Spain; Laila Irene Bruun, Oslo University Hospitals, Oslo, Norway; Birgit Eiermann, Karolinska Institutet, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Stockholm, Sweden; Annsofie Fyhr, Pharmaceutical Supply, Operational Support and Service, Jönköping County Council, Sweden; Allen R. Huang, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Canada; Karin Dorner, Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt Wien, Vienna, Austria; Lilian Brøndgaard Nielsen, Hospital Pharmacy Central Denmark Region, Horsens, Denmark; Juan Ortiz de Urbina, Hospital de Leon, Leon, Spain; Diane Seger, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA; Anne Marie Timenes, Oslo University Hospitals, Oslo, Norway).

Funding

The study was supported by the Federal Ministry of Health, Germany [#2512 ATS 002] and a final report in German is available online.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests with regard to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seidling, H.M., Stützle, M., Hoppe-Tichy, T. et al. Best practice strategies to safeguard drug prescribing and drug administration: an anthology of expert views and opinions. Int J Clin Pharm 38, 362–373 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0253-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0253-1