Abstract

Background Non-adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses is considered the major reason why patients fail to reach their clinical goals, resulting in suboptimal health outcomes, death, and extra costs on the health care systems. Knowledge about the disease and prescription medications, an understanding of the reason the medication is needed, and good expectations or attitudes toward treatment, all contribute to a better medication-taking behavior and are associated with higher rates of adherence. Objective This study examines the relationship between knowledge and adherence of patients receiving long-term therapy for one or more chronic illnesses in Jordan. Settings The study was conducted in the out-patient clinics of two Jordanian hospitals (The University of Jordan Hospital and Jordan Hospital). Methods This was a cross-sectional study that included 902 patients. The correlation between patients’ knowledge about their chronic medications and adherence was assessed. Effects of several sociodemographic characteristics were investigated in regard to knowledge and adherence. Main outcome measures Knowledge was assessed by a modified version of the McPherson index, and the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale was used to assess medication adherence. Results A significant correlation was found between patients’ knowledge and their adherence to medications (r = 0.357, p < 0.001). Most of the participants had low adherence. Younger age, higher education levels, high income, fewer medications and diseases were significant predictors of higher knowledge levels. Knowledgeable patients were found to be twice as likely to have moderate-to-high adherence as their unknowledgeable counterparts. Similarly, high income and higher education were associated with higher adherence scores. Conclusion Forgetfulness and aversion toward medications were the most common barriers to medication adherence. This implicates that clinicians and health care policy makers should direct their effort toward two main strategies to improve adherence increasing awareness and education of effective ways to remind patients about their medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact of findings on practice

-

Jordanian hospital patients have three gaps in their knowledge about medications: side effects, the behavior toward missing doses and when to take the medication.

-

Adherence of Jordanian hospital patients to their medications is affected by two major barriers: forgetfulness and reluctance toward medications.

-

In Jordan, future strategies to improve patients’ knowledge and adherence in the aforementioned aspects are warranted.

Introduction

Adherence to medication is defined as the extent to which a person’s behavior in taking medication corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider [1]. Non-adherence is considered a major reason why patients fail to reach their clinical goals, resulting in suboptimal health outcomes, death, and extra costs on the health care systems [2–4]. This burden has been estimated to cost the US approximately $100 billion per year and to be the main reason for increases in the number of emergency department visits among patients affected by chronic disorders [3, 5–7]. In addition, approximately 125,000 deaths occur annually in the US due to non-adherence to cardiovascular medications [2, 3]. Despite this, adherence rates to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses remain to be low [4]. Data show that, in developed countries, adherence among patients suffering chronic diseases ranges from 20 % to only 50 %, while, in developing countries, the rates are assumed to be even lower given the paucity of health resources and inequities in access to health care [1, 8–10]. Adherence was shown to decline with time even after life-threatening events such as a stroke, and it is thus supposed that compliance to treatment for chronic asymptomatic conditions—to prevent the possible occurrence of adverse events—represents an even greater challenge to be solved [11]. Of all age groups, older persons with chronic diseases benefit the most from taking their medicines, and risk the most from failing to take them properly [1]. Different factors or ‘dimensions’ determine adherence [1]: (1) the social/economic factors, (2) the health care system, (3) the disease’s characteristics, (4) the disease therapies, and (5) the patient-related factors. In particular, increasing the impact of interventions aimed at patient-related factors showed to be essential and highly effective to improve adherence [1].

Knowledge about the disease, an understanding of the reason the medication is needed, and positive expectations or attitudes toward treatment, all contribute to a better medication-taking behavior [1, 4, 12]. In this regard, improvements in the patient’s knowledge regarding their prescriptions bear a favorable effect on the medication adherence among those under chronic oral treatment [13].

Data revealed that many patients who are newly starting a chronic medication quickly become non-adherent expressing a substantial and sustained need for further information [14]. In addition, non-adherence is significantly associated with disease-related knowledge and with the patient’s beliefs about the necessity of their medications and the possible adverse effects [15, 16].

In patients with diabetes mellitus, a strong positive association was found between the knowledge of their diabetes medications and the glycemic control which was found poorer among those not adherent to medications [17, 18]. Similarly, low medication adherence was associated with low treatment satisfaction with antipsychotics and poor psychiatric score in people with schizophrenia [19], while, exposure of patients with hypertension to a short-term adherence therapy was sufficient to reduce blood pressure and improve their adherence to medication [20].

In an effort to better understand the patients’ medication-taking behaviors, researchers have differentiated between two types of non-adherence, intentional and unintentional [9]. In this study, the validated 8-item Morisky scale was used to identify patients with adherence problems. It is based on the intentional/unintentional non-adherence classification and recognizes these two main types of non-adherence using eight items [21]. However, it does not reveal the underlying cause for this burden and thus a separate question was added to identify the major driver(s) of low medication adherence in the Jordanian population [22, 23]. With a greater understanding of when and why non-adherence occurs, we might be able to intervene effectively before it becomes established.

Aim of study

The aim of this study was to assess the rate of adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses in Jordan and to find whether lack of medication knowledge was linked to patients’ self-reported medication non-adherence. This will indirectly reveal the importance of patient counseling over the time to improve their adherence to prescriptions as well as the important role that clinical as well as community pharmacists must play in the Jordanian health care system.

Ethical approval

The study was designed to comply with the code of ethics of the declaration of Helsinki. All study participants were fully briefed, and data was collected only for those patients who provided their consent.

Methods

Study subjects

The study was conducted in the out-patient clinics of two Jordanian hospitals (The University of Jordan Hospital and Jordan Hospital). Adult patients, with age of 18 years old or more who had been taking medications for at least 3 months and had a minimum of one chronic condition were included in the study. Examples of chronic conditions include hypertension, asthma, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. Patients who could not communicate in Arabic or with mental disability were excluded from this study.

Study design and data collection

This was a cross sectional survey which was carried out from November 2013 to July 2014. Data was collected from 902 patients by a questionnaire through a 5 to 10-min face-to-face interview.

In addition to our exposure and outcome variable of interest, i.e. medication knowledge and adherence respectively, socio-demographic variables were collected such as age, gender, number of chronic diseases and of medications, education level, income, insurance and marital status. Knowledge was assessed by a modified version of the McPherson index [13, 17]. During the interview, participants were asked to list all the currently prescribed medications (brand name and/or scientific name), their indications (use and/or specific mechanism of action), directions for use, adverse effects (at least one of each prescribed medication) and what to do if they missed a dose (Medication knowledge assessment tool available as electronic supplementary material). The participants were considered knowledgeable if they were able to identify the aforementioned information about all their medications. The number of correct responses was used to assess the total medication knowledge score. Thereafter, the total medication knowledge score was evaluated out of seven for each participant.

Self-reported medication adherence was measured by the Arabic-translated 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). The MMAS-8 proved to be reliable (alpha = 0.83) with good concurrent and predictive validity in patients with hypertension and might function as a screening tool in clinical settings with other patient groups [19, 21, 24–26]. It comprises eight questions that recognize intentional and unintentional non-adherence: “Do you sometimes forget to take your medication?” (unintentional), “In the past 2 weeks, were there any days you did not take your medication for any reason other than forgetting?” (intentional), “Have you ever cut back or stopped taking your medication without telling your doctor because you felt worse when you took it?” (intentional), “When you travel or leave home, do you sometimes forget to bring along your medications?” (unintentional), “Did you take your medication yesterday?” (unintentional), “When you feel better, do you sometimes stop taking your medicine?” (intentional), “Taking medication every day is a real inconvenience for some people. Do you ever feel hassled about sticking to your treatment plan?” (intentional), “How often do you have difficulty remembering to take all your medications?” (unintentional). Response categories were yes/no for each item, scored 1/0 respectively. Highly adherent patients were identified with the score of 8 on the scale, medium adherers with a score of 6 to <8, and low adherers with a score of <6 [21].

Statistical analysis

The baseline demographic variables were summarized and compared using the independent sample U-Mann Whitney test. Patients’ adherence was treated as a dichotomous variable with a cut-off value of 6. Patients’ knowledge was decoded similarly and considered as a dichotomous variable with a cut-off value of 4. The correlation between patients’ knowledge and adherence was examined using logistic regression accounting for covariates. The effects of other factors such as insurance status, income and number of medications on adherence were assessed using Chi square. IBM SPSS® 20 software was used to perform the statistical analysis (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, 2011, USA). All hypothesis testing was two-sided, with a probability value (p value) of <0.05 deemed as significant.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the 902 participants included in this study are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the respondents was 55.4 ± 13.8 years, with 36.6 % older than 60 years, and 57.5 % female. A total of 50.7 % of the responders received a higher education, 75.5 % had an intermediate income and 85 % were married. Most of the patients (82.2 %) had three or fewer chronic diseases and were receiving four or less medications (67.4 %). The mean number of diseases was 2.4 ± 1.4 and the mean number of prescribed medication was 3.9 ± 2.63. In addition, medical insurance was observed in 75.2 % of our sample.

The knowledge score ranged between 0 and 7 with a mean ± SD value equals to 3.7 ± 1.7. The median score was 4. Most of the patients were aware about their medication names, why they were on these medications and how to take them. Poor knowledge was observed in particular with question number 5: ‘Do you know the possible side effects of your medication?’ with 85.6 % of non-responders (Table 2). Only 1.4 % of the population was able to answer correctly all the medication knowledge questions. Using the median medication knowledge score of 4, we compared patients’ characteristics between those with a high score (≥4) and those with a low score (<4). Based on this categorization, 62.3 % of the population was found to have a high knowledge score while 37.7 % were recognized as not knowledgeable.

The mean ± SD medication adherence score was 5.2 ± 1.8. Just 6.7 % of the participants were highly adherent to their medications, identified with a score of 8 on the scale, 19.9 % were medium adherent with a score of 6 to <8 on the scale while most of the population (73.4 %) were non adherent to their medications (score < 6). Most of the patients forgot sometimes to take their medication and were also feeling hassled about sticking to their treatment plan. This is in accordance with the reasons that mostly affect patients’ adherence, as 38.4 % of the participants found ‘forgetfulness’ the main barrier to stick to their regimen and 13.6 % stated that ‘they don’t like medicines’. In addition, 11.6 % of the population found ‘other’ reasons than those mentioned in Table 3 as the major barrier to adherence (Table 3). One ‘other’ reason most commonly expressed by the patients was running out of prescription from the hospital, which mainly concerns patients with high level of insurance.

A significant positive relationship between the total medication knowledge score and the medication adherence scale was found. The Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient was r = 0.357 (p < 0.001). Correct classification of adherence was based on the dichotomous low versus high knowledge score and had a rate of 73.4 %.

The effect of each item in the medication knowledge assessment tool on medication adherence was investigated showing that patients’ knowledge regarding their chronic medication names, how to take them, what to do if side effects occurred and what to do if a dose was missed, were all associated with a greater adherence to medication regimens (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

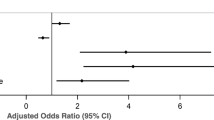

In the multivariate model, age, gender, education, income, marital status, number of medications, number of diseases, and insurance were evaluated with respect to medication knowledge or adherence. Odd ratios of the predictors with a significant p value are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

Logistic regression showed a significant relationship between high medication knowledge and medication adherence (OR = 2.14). As shown in Table 5 and 6, patients with higher education and those with higher income were found to have both higher knowledge and adherence levels. Moreover, younger patients, those with fewer chronic diseases and fewer medication as well as patients without any type of insurance were all significantly more likely to have a higher knowledge score (Table 5).

Discussion

This is a two-site cross-sectional study which was conducted in Jordan, the aim of which is to assess the rate of adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses and to find whether or not the lack of medication knowledge was linked to patients’ self-reported medication non-adherence. The majority of our sample is comprised of patients who are receiving four or less medications for three or less diseases. When knowledge about the use of medications was evaluated as a score out of 7, patients were found to be modestly knowledgeable with about 60 % having a score of equal to or >4. Expectedly, younger age, higher education levels, high income, less medications and fewer diseases were significant predictors of higher knowledge levels. Interestingly, patients without medical insurance were more knowledgeable about their medications, which might indicate that when patients pay for their medication and medical visits, they tend to educate themselves more about their disease and/or prescription medications. On the other hand, more than 70 % of the patients were considered low adherers, with forgetfulness, and aversion to medications being the most common reasons of non-adherence. Higher education and income were associated with higher adherence levels.

Our results show that there was a significant relationship between knowledge about medications and tendency to adhere to long-term treatments. Logistic regressions showed that knowledgeable patients are twice as likely to have moderate-to-high adherence as their unknowledgeable counterparts. Specifically, patients’ knowledge regarding the names of their medications, how to take them, what to do if side effects occurred and what to do if a dose was missed, were all associated with a greater adherence to medication regimens.

To our knowledge, this is the largest, two-site study to evaluate the relationship between knowledge about chronic medications and adherence in Jordan. Several studies have also attempted to identify the factors associated with adherence to chronic medications for certain classes of drug therapy in Jordan [18, 20, 27]. Similarly, most of the available studies focused on the adherence to medications prescribed for the management of one illness, such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension [16, 20, 21, 27–29]. Others focused on the adherence to only one oral chronic medication, not all chronic prescription items [13]. All of these studies identified knowledge as a major predictor for patient medication non-adherence contributing to a poorer control of the disease. Our study included patients with any type of chronic illness, making our results more generalizable to other diseases. In addition, our study used a validated, reliable tool for the assessment of medication adherence, the 8-item Morisky scale, which covers both intentional and non-intentional classes of non-adherence. To further recognize the reason(s) that mostly impede(s) the Jordanian patients from taking their medication, a separate question was added. This was not done in previous similar studies [13, 16, 20, 29].

Our study is limited by the inherent nature of cross-sectional studies, which lack the ability to identify causation and only allow detecting an association between knowledge and adherence. Although we had collected data from patients in two major hospitals in Amman, the capital of Jordan, where most Jordanians seek medical services, we still cannot generalize results obtained from these two medical centers to others in the same city or different cities of Jordan. Moreover, patients with mental disorders or those unable to communicate in Arabic were not included in the study which might have led to the over estimation of adherence by including patients with higher level of cognition and educational status.

Like studies based on self-reported measures, this study is liable to recall bias. reflection of adherence is always dependent on the honesty of responders; some might not disclose non-adherence as it might be deemed undesirable behavior, especially as this study was a face-to-face interview. Another limitation of our study is that it did not evaluate the relationship between adherence and whether or not the disease was controlled. Since this study included patients with multiple long-term diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and respiratory system diseases, it would have been complicated to monitor each patient for the different parameters associated to each disease’s control.

Conclusion

Our study shows that forgetfulness and aversion toward medications were the most common barriers to medication adherence. This implicates that clinicians and health care policy makers should direct their effort toward two main strategies to improve adherence, increasing awareness and education of effective ways to remind patients of their medications such as caregiver assistance, memos, or reminders. In addition, health care providers should seek methods to improve patients’ perceptions and beliefs about their medications. This study indicates that although our patients are modestly knowledgeable about their medications, the majority of them lack knowledge in certain aspects related to their medications, namely, the timing of their medications, side effects of their medications, and their attitudes toward side effects and missed doses. Again, interventions by health care providers especially pharmacists, to counsel patients and increase their knowledge with regard of the aforementioned aspects is pivotal. Future research should aim to evaluate the effect of various strategies which enhance patients’ memory, improve their beliefs or increase patients’ medication knowledge on patients’ adherence to long-term medications.

References

De Geest S, Sabate E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(4):323.

McCarthy R. The price you pay for the drug not taken. Bus Health. 1998; 16(10): 27-8, 30, 2-3.

Bosworth HB, Granger BB, Mendys P, Brindis R, Burkholder R, Czajkowski SM, et al. Medication adherence: a call for action. Am Heart J. 2011;162(3):412–24.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97.

Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(5):331–42.

Hope CJ, Wu J, Tu W, Young J, Murray MD. Association of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(19):2043–9.

Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43(6):521–30.

Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):304–14.

Gadkari AS, McHorney CA. Unintentional non-adherence to chronic prescription medications: how unintentional is it really? BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:98.

Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD000011.

Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on patients. Am J Med. 2012;125(9):882–7.

Jin J, Sklar GE, Oh VMS, Li SC. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient’s perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):269–86.

Okuyan B, Sancar M, Izzettin FV, Morisky DE. Erratum to and corrections on the article entitled “Assessment of medication knowledge and adherence among patients under oral chronic medication treatment in community pharmacy settings”. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(2):218–20.

Barber N, Parsons J, Clifford S, Darracott R, Horne R. Patients’ problems with new medication for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(3):172–5.

Quinlan P, Price KO, Magid SK, Lyman S, Mandl LA, Stone PW. The relationship among health literacy, health knowledge, and adherence to treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. HSS J. 2013;9(1):42–9.

Sweileh WM, Zyoud SH, Abu Nab’a RJ, Deleq MI, Enaia MI, Nassar SM, et al. Influence of patients’ disease knowledge and beliefs about medicines on medication adherence: findings from a cross-sectional survey among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Palestine. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:94.

McPherson ML, Smith SW, Powers A, Zuckerman IH. Association between diabetes patients’ knowledge about medications and their blood glucose control. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2008;4(1):37–45.

Khattab M, Khader YS, Al-Khawaldeh A, Ajlouni K. Factors associated with poor glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat. 2010;24(2):84–9.

Sweileh WM, Ihbesheh MS, Jarar IS, Sawalha AF, Abu Taha AS, Zyoud SH, et al. Antipsychotic medication adherence and satisfaction among Palestinian people with schizophrenia. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2012;7(1):49–55.

Alhalaiqa F, Deane KH, Nawafleh AH, Clark A, Gray R. Adherence therapy for medication non-compliant patients with hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26(2):117–26.

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10(5):348–54.

Aburuz SM, Bulatova NR, Yousef AM, Al-Ghazawi MA, Alawwa IA, Al-Saleh A. Comprehensive assessment of treatment related problems in hospitalized medicine patients in Jordan. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(3):501–11.

Basheti IA, Qunaibi EA, Bulatova NR, Samara S, AbuRuz S. Treatment related problems for outpatients with chronic diseases in Jordan: the value of home medication reviews. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(1):92–100.

Aljumah K, Ahmad Hassali A, AlQhatani S. Examining the relationship between adherence and satisfaction with antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1433–8.

Cantudo-Cuenca MR, Jimenez-Galan R, Almeida-Gonzalez CV, Morillo-Verdugo R. Concurrent use of comedications reduces adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(8):844–50.

Fabbrini G, Abbruzzese G, Barone P, Antonini A, Tinazzi M, Castegnaro G, et al. Adherence to anti-Parkinson drug therapy in the “REASON” sample of Italian patients with Parkinson’s disease: the linguistic validation of the Italian version of the “Morisky Medical Adherence Scale-8 items”. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(11):2015–22.

Jarab AS, Alqudah SG, Mukattash TL, Shattat G, Al-Qirim T. Randomized controlled trial of clinical pharmacy management of patients with type 2 diabetes in an outpatient diabetes clinic in Jordan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(7):516–26.

Garcia-Perez LE, Alvarez M, Dilla T, Gil-Guillen V, Orozco-Beltran D. Adherence to therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2013;4(2):175–94.

Lee GK, Wang HH, Liu KQ, Cheung Y, Morisky DE, Wong MC. Determinants of medication adherence to antihypertensive medications among a Chinese population using Morisky Medication Adherence Scale. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e62775.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful the logistic support from the Deanship of Academic Research at the University of Jordan, the University of Jordan Hospital, and the Jordan Hospital.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the Deanship of Academic Research at the University of Jordan.

Conflicts of interests

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Awwad, O., Akour, A., Al-Muhaissen, S. et al. The influence of patients’ knowledge on adherence to their chronic medications: a cross-sectional study in Jordan. Int J Clin Pharm 37, 504–510 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0086-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0086-3