Abstract

Mo–Si–B alloys were obtained by spark plasma sintering (SPS) using fine Mo–Si–B alloy powders with a particle size of 2.5 μm. The SPS Mo–Si–B alloys consisted of fine MoSi2/Mo2Bi5(Mo5Si3)/MoB/SiO2 phases. Under isothermal conditions, the weight-gain kinetics of the Mo–Si–B alloys obtained by SPS exhibited parabolic time dependence and these Mo–Si–B alloys showed better oxidation resistance at moderate temperatures of 500 °C and 600 °C with no “pest” failure. The oxide scale on the sample surface consisted of MoO3, amorphous borosilicate and crystalloid SiO2 phases. An increase in the oxidation temperature from 500 to 600 °C caused a significantly higher fluidity and a shorter incubation stage for the formation of a continuously protective borosilicate layer, so that the mass gain was smaller than 1 mg/cm2 for oxidation at 600 °C for 100 h, which corresponds to the excellent oxidation resistance.

Graphic Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

MoSi2-based composites can be used as heating elements and oxidation-resistant coatings at temperatures up to 1600 °C. However, MoSi2 may suffer severe corrosion and become crushed into powder under oxidation at moderate temperatures, in particular, at temperature between 400 and 550 °C [1,2,3]. This phenomenon was first described by Fitzer [4], who defined it as the phenomenon of the “MoSi2 pest.” The “MoSi2 pest” has been recognized to be strongly related to MoO3 scale formation. The volume expansion stress introduced by the MoO3 gives rise to cracking and fragmentation of the scale, which exposes the substrate and accelerates the oxidation process [5, 6]. Generally, the microstructure and relative density of MoSi2, the atomic ratio of Mo and Si and the oxidation temperature play the key roles in the “pest” phenomenon. The fragmentation of the “pest” samples is closely dependant on the relative density and content of defects in the sample. An MoSi2 sample with the relative density of 67% was reported to exhibit pest oxidation even under exposure to air at 400 °C for 10 h, whereas the initiation time of the pest was extended considerably to 350 h when the relative density was increased to 86% [7]. These results reveal that the low relative density promotes the “MoSi2 pest.” The Mo-rich Mo–Si alloy is more susceptible to the “pest” phenomenon than the pure MoSi2 alloy, because a Mo5Si3 phase present in the Mo-rich Mo–Si composition in addition to the MoSi2 phase is detrimental to the low-temperature oxidation resistance [8]. Moreover, the atmospheric conditions such as high oxygen partial pressures (air and oxygen) and water partial pressure were found to decrease the critical temperature at which the peak mass gain of MoSi2 was obtained [9]. At the temperatures in the 600 °C to 700 °C range, the MoSi2 compound does not show the “pest” phenomenon, but still undergoes accelerated oxidation due to the partial volatilization of molybdenum oxide in the oxide scale formed on the surface [1, 2]. The volatilization of the molybdenum oxide results in the presence of voids in the oxide scale, and these voids then become the channels for the oxygen diffusing into the substrate.

Adding boron to change the oxide scale from silica (SiO2) to borosilicate (SiO2·B2O3) is an effective approach for suppressing the “MoSi2 pest” phenomenon [10]. The introduction of the B2O3 into the SiO2 decreases the scale-product viscosity (i.e., increase the fluidity) on the MoSi2 surface, so that the borosilicate can rapidly heal the cracks and form a continuous and dense layer to hinder the further attack of the oxygen [11,12,13,14]. It was reported that at 500 °C, the monolithic MoSi2 compound showed a mass gain of 2.3 mg/cm2 when oxidized for 100 h; by contrast, with the B addition, no destructive oxidation was observed and the mass gain after 80 h of oxidation at 500 °C was 1.4 mg/cm2 [10]. Moreover, the oxidation kinetics changed from following a linear law in the monolithic MoSi2 to following a parabolic law in the boronized MoSi2 [15,16,17,18,19,20].

To date, the dependence of the oxidation resistance of the MoSi2 compound on the B content and the changes in the oxidation mechanism when the oxidation temperature increases from 500 to 600 °C have not been systematically investigated. In this work, the oxidation behaviors of Mo–62Si–5B, Mo–57Si–10B and Mo–52Si–15B alloys prepared by spark plasma sintering (SPS) at low temperatures (500 °C and 600 °C) were investigated. The oxidation kinetics were recorded, and the morphology evolution of the oxide scale formed on the specimens was characterized to elucidate the effect of B content on the “pest” behavior and oxidation resistance at moderate temperatures. Finally, the changes in the oxidation mechanisms of the Mo–Si–B ternary alloys at 500 °C and 600 °C are discussed.

Experimental Procedures

Specimen Preparation

Ingots of the Mo–62Si–5B, Mo–57Si–10B and Mo–52Si–15B alloys (at%) were prepared using an arc-melting furnace under argon atmosphere. The purity of the constituent elements (i.e., Mo, Si and B) was at least 99.9% (mass). To ensure chemical homogeneity, the ingots were repeatedly melted and solidified six times. The weight loss during the melting process was negligible. Then, the arc-melted ingots were manually smashed and ball-milled to powder with a particle size of approximately 2.5 μm. Ball milling was performed for 1 h using planetary ball mill (QM-QX, NanDa Instrument Plant, China) at room temperature under argon atmosphere. The ball-to-powder weight was kept at 8:1 and the rotation speed was 400 rpm. The powder (15 g) was poured into a graphite die (20 mm in diameter) for sintering at 1500 °C under a pressure of 50 MPa using a spark plasma sintering system (SPS-1050 Sumitomo Co.). Finally, three SPS samples with high relative density, which was larger than 98.5%, named the 5B sample (sintered Mo–62Si–5B powders), the 10B sample (sintered Mo–57Si–10B powders) and the 15B sample (sintered Mo–52Si–15B powders), were obtained.

Oxidation Tests

The cylindrical specimens cut from the SPS samples were used to evaluate the moderate-temperature oxidation behavior of the Mo–Si–B ternaries. The diameter and height of the oxidation specimens were 8 mm and 3 mm, respectively. Isothermal oxidation tests were carried out at 500 °C and 600 °C using an open-ended tube furnace in air. The specimens were placed in an alumina crucible and were held in the uniform hot zone of the furnace. During the oxidation process, the cylinders were placed in an alumina crucible and the gross weight (sample and alumina crucible) was measured. The mass gains of the oxidized samples were measured at the intervals of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 h using an analytical balance with the accuracy of 10−5 g (Model CPA225D, Germany). Furthermore, six additional samples of each alloy at each oxidation temperature were isothermally oxidized for 1, 2, 5, 20, 50 and 100 h.

Characterizations

The phase and microstructure evolution of the oxide layers were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Model D/M-2500PC Rigaku, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation and by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Model 200F, Holland). Metallographic cross section of the oxidized specimens was prepared by mounting in cold-setting resin followed by abrading on SiC paper to a 2000 grit finish and finally polishing to a 1-μm diamond finish. Phase compositions were obtained using an electron microprobe analysis instrument (EPMA, Model JXA-8230, Japan; the spot diameter is 1 µm). Based on measurements of the oxide layer thickness from the nine different positions of cross section using a ruler tool, an average value of the oxide layer thickness was determined. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to further identify the structure of the oxide scale formed on the sample surface using a JEOL JEM-2100F microscope. Preparation of the TEM samples was described elsewhere [21].

Results

Microstructures of the 5B, 10B and 15B Alloys

The microstructures of three spark plasma sintered alloys are shown in Fig. 1. For the 5B alloy (Fig. 1a), four phases, namely the gray MoSi2 matrix, light gray Mo5Si3 particles, bright MoB and equiaxed black SiO2, were observed. As the B content increased up to 10 at% and 15 at%, bright Mo2B5 particles were found in addition to the gray MoSi2, black SiO2 and small gray MoB phases, as shown in Fig. 1b, c. Previous studies have confirmed that SiO2 is formed via the MoSi2 reacting with oxygen impurities in argon atmosphere during the SPS process [21, 22]. The dependence of the phase composition of the Mo–Si–B alloys obtained by SPS on the nominal B contents is in good agreement with the previous works [21, 22] and the Mo–Si–B ternary diagram [23].

Oxidation Kinetics of the SPS Samples at 500 °C and 600 °C

Oxidation kinetics curves of the Mo–Si–B samples oxidized at 500 °C and 600 °C for 100 h are shown in Fig. 2. There was no pest phenomenon, and the mass gains for the three alloys were negligibly small at the experimental temperatures. The weight gain of the three specimens during the oxidation showed a faster and linear increase in the initial 20 h, while its slope was close to the linear rate constant of the oxygen–silicon reaction [20]. After oxidation for 20 h, corresponding to the formation of a protective oxide scale, the weight gain of the three specimens showed parabolic variation with the oxidation time. It is clear that an increasing B content decreased the weight gain and the 15B sample always showed the smallest weight gain for various times. For example, when oxidized at 500 °C for 100 h, the weight gain of the 15B alloy was 0.7 mg/cm2, compared to 0.85 mg/cm2 for the 10B alloy and 1.10 mg/cm2 for the 5B alloy. At 600 °C, as observed from Fig. 2b, the faster and linear increase in the weight gain ended at the beginning of 5-h oxidation, and then, the oxidation kinetics showed a parabolic behavior. It should be emphasized that the weight gains of the three alloys oxidized at 600 °C were less than those of the corresponding alloys oxidized at 500 °C, and an increasing B content increased the weight gain, as shown by the comparison of Fig. 2b to a. After oxidation at 600 °C for 100 h, the weight gain of the 5B alloy was 0.17 mg/cm2 and increased to 0.20 mg/cm−2 for the 10B alloy and 0.38 mg/cm−2 for the 15B alloy, thereby revealing the superiority of the oxidation resistance at 600 °C of the Mo–Si–B alloys compared to that at 500 °C. The linear relationship between the mass gain (y) of the three SPS samples and the square root of oxidation time (√t) shown in Fig. 2c, d further confirms the parabolic law of the kinetics curves of the Mo–Si–B alloys at 500 °C and 600 °C, with the parabolic rate constant kp calculated according to y2= kpt shown in Fig. 2c, d. The mass gains and corresponding kp values suggest that excessive B addition improves the oxidation resistance at 500 °C, but slightly degrades the oxidation resistance at 600 °C.

Phase Constitution of the Oxide Products

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of the oxidized surfaces of the Mo–Si–B samples after oxidation at 500 °C for 5 h, 50 h and 100 h (Fig. 3a–c) and at 600 °C for 100 h (Fig. 3d). The surfaces of three SPS samples showed similar X-ray profiles at each oxidation time and temperature, independent of the nominal B content, revealing stable oxide products most likely composed of MoO3, SiO2, MoB and MoSi2. Previous studies have confirmed the characteristic X-ray peaks of the MoSi2 and MoB phases from the alloys because the oxide layer was too thin [21, 22]. Considering the reaction of the dominant MoSi2 phase with oxygen, the oxide products present on the Mo–Si–B sample surfaces were preliminarily identified to contain SiO2 and MoO3, which is temporarily called the complex SiO2–MoO3 oxide scale.

A comparison of the SEM micrographs of the Mo–Si–B sample surfaces after oxidation in air for 100 h at 500 °C and 600 °C is shown in Fig. 4. An examination of the inset images of the macro-morphologies of the oxidized Mo–Si–B samples reveals that the samples were still intact after oxidation and no fragmentation by “pesting” occurred. From the enlarged images, it is observed that the lump-like particles distributed on the flat matrix when oxidized at 500 °C and 600 °C for 100 h. EDS analysis revealed that the lump-like particles were SiO2, while the flat matrix was an oxide containing of the Si, O, Mo and B, perhaps corresponding to a mix of MoO3, SiO2 and B2O3 (based on the analysis by TEM, shown in Fig. 7). Comparison of Fig. 4d–f to Fig. 4a–c found that the number density of lump-like SiO2 particles on the surfaces of the samples oxidized at 600 °C was less than that on the surfaces of the samples oxidized at 500 °C. In addition, needle-shaped MoO3 was observed on all the surfaces of the samples oxidized at 500 °C (Fig. 4), which is consistent with the results of XRD pattern and EDS.

Microstructural Evolution of the Oxide Scale at 500 °C and 600 °C

Figure 5 shows representative cross-sectional morphologies of the 5B and 15B samples after oxidation at 500 °C for different times. During the 100-h oxidation, the oxide layer of the 5B sample grew continuously (Fig. 5b) and finally reached the thickness of 23.7 ± 2.9 μm (Fig. 5c). Moreover, some voids and cracks existed in the continuous oxide layer, as observed in Fig. 5b, c. The evolution of the oxide scale of the 15B sample shown in Fig. 5a’–c’ was quite similar to that of the oxide scale on the 5B sample. However, compared to the 5B sample, the oxidized 15B sample showed a more uniform and denser oxide scale (20.6 ± 1.9 μm in thickness) when oxidized at 500 °C for 100 h. The oxide scale of 10B sample is not discussed here because it has the same microstructure as the oxide scales of the 5B and 15B samples.

The SEM image and the element mappings of the oxide products formed on the SPS 15B sample surface during air exposure at 500 °C for 100 h are shown in Fig. 6. The element distributions confirmed the enrichment of O, Si and Mo in the non-dense oxide scale (Fig. 6b–d). Moreover, B enrichment was clearly found in the oxide scale (Fig. 6e), revealing the formation of amorphous B2O3 via a reaction of MoB with oxygen, as indicated by the absence of the characteristic peaks of crystalloid B2O3 in the XRD profiles (Fig. 3) [21, 22]. It is postulated that the B enrichment zone in the oxide scale shown in Fig. 6e indirectly confirms the coalescence of the amorphous borosilicate during the oxidation process. As such, the oxide products contained amorphous borosilicate and the crystalloid SiO2 and MoO3.

To further identify the structure of the Mo–Si–O–B oxide matrix, the oxide scale of the 15B alloy formed after oxidation at 500 °C for 100 h was examined by TEM, with the obtained images shown in Fig. 7. In addition, Table 1 lists the atomic fraction in the three different positions (marked by box) obtained by EDS analysis. Figure 7a shows a TEM image of the Mo–Si–O–B oxide scale, in which black particles 10–200 nm in size can be seen dispersed in the matrix of the oxide products. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns (with the beam [100] (zone axis) shown in Fig. 7a) and EDS analysis of the particle (a) confirmed that the nanosized particles were the MoO3 phase. A higher-resolution TEM lattice image of the area indicated by box b in Fig. 7a is shown in Fig. 7b. It is clear that the MoO3 particle had an ordered atomic arrangement while the adjacent oxide matrix showed a disordered atomic arrangement. The enlarged image of the rectangle in Fig. 7a showed that the disordered zones of the oxide scale had an amorphous structure and they should be borosilicate [21, 22]. Moreover, some clusters with ordered atomic arrangement (circles in Fig. 7c) were found to be distributed in the disordered atomic arrangement zones. These ordered atomic clusters shown in circles in Fig. 7d should be the crystalloid SiO2, as was confirmed from the X-ray profiles (Fig. 3) and EDS analysis. Thus, the microstructure of the multicomponent Mo–Si–O–B oxide matrix was finally confirmed to be nanometer-size MoO3 particles and crystalloid SiO2 clusters embedded in the amorphous borosilicate matrix.

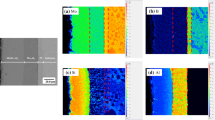

Representative SEM micrographs of the cross sections of the 5B and 15B samples oxidized at 600 °C for 5 h, 50 h and 100 h are shown in Fig. 8. Compared to that at 500 °C, the oxide scale had no obvious defects (Fig. 5). In the entire 100-h oxidation process, the oxide scale grew very slowly and uniformly only to the thickness of approximately 1 μm (Fig. 8c), whereas the oxide scale thickness was as high as 20 μm when oxidized at 500 °C for 100 h. We note that the XRD patterns of the 5B, 10B and 15B samples oxidized at 600 °C for 100 h were quite similar to those of the three samples oxidized at 500 °C for 100 h (comparison of Fig. 3d to c). Therefore, the oxide products formed on the surfaces of the Mo–Si–B samples oxidized at 500 °C and 600 °C were believed to be identical, i.e., the amorphous borosilicate matrix embedded with the nanoscale MoO3 particles and the crystalloid SiO2 clusters, as well as the amorphous lump-like SiO2 particles on the matrix surface.

Discussion

The diffusion of oxygen through borosilicate is much slower than that through the discontinuous or porous oxide scale and the substrate [9]. Previous studies [24,25,26,27] have shown that the addition of boron to glass-like SiO2 decreases the viscosity (increases the fluidity) of the oxide products. In this case, the sample surface can be covered by the oxide products with high fluidity; as a result, the defects such as cracks and voids in the sample surface and in the oxide products are sealed. Thus, whether or not a continuous, dense and protective borosilicate-dominant oxide scale is quickly formed depends on fluidity of the oxide products and the amounts of MoO3 and SiO2.

Yan et al. [13] reported a relationship of the viscosity of the borosilicate to the temperature and the nominal B content by the following equation [13]:

where η is the viscosity of the borosilicate in poise, T is the temperature in K and x (0 < x<0.4) is the atom fraction of boron content defined as (SiO2)1−x(B2O3)x. The viscosity of the borosilicate as a function of B content at 500 °C and 600 °C is plotted in Fig. 9. It is clear that for the B content of less than 10%, the viscosity of SiO2 drops dramatically with increasing B content, whereas a slow decrease trend is observed upon the further B addition. Moreover, the viscosity of SiO2 at 500 °C is estimated to be 10–1000 times higher than that at 600 °C. For example, the η value of the 15B alloy at 600 °C is 1010.8 Pa s, while it is 1013.5 Pa s at 500 °C.

Apparently, the thicker and fluffy morphology of the borosilicate-dominant oxide scale reveals that the viscosity of the borosilicate at 500 °C is insufficient for rapid formation of a protective oxide scale. It is generally recognized that the non-protective characteristic of MoSi2 at low temperature is due to the volume expansion and occurrence of cracks. According to the calculation of Yanagihara et al. [5], MoO3 formation is described by the following reactions:

which may result in a volume expansion of approximately 212%. The MoO3 compound shows strong tendency to evaporate at high temperatures, and the evaporation rate for MoO3 increases exponentially at temperatures above 600 °C [19]. However, the evaporation rate of MoO3 is almost negligible for oxidation at 500 °C and, therefore, most of the MoO3 remains in the oxide scale (greater intensity of the diffraction characteristic peaks of MoO3 in Fig. 3). In this case, the volume expansion of MoO3 makes the oxide scale form an open structure with cracks and voids, facilitating the rapid diffusion of oxygen through these defects toward the substrate and increasing the oxidation rate [18]. Moreover, the MoO3 particles embedded in amorphous borosilicate (Fig. 7) may also mechanically impede the flowing of the borosilicate so that the borosilicate cannot quickly spread over the entire surface of the substrate as a continuous and dense product, thus not providing effective protection for the substrate (Fig. 5). Compared to the oxidation behaviors of the pure MoSi2 compound (almost 3.90 mg/cm−2 when oxidized at 500 °C for 70 h [9]), it is concluded that the addition of B effectively suppresses the “pest,” decreases the mass gain and increases the oxidation resistance of the MoSi2 compound at 500 °C. The higher B content leads to higher scale fluidity (Table 2), and hence better oxidation resistance compared to a lower B content sample (Fig. 2a). It should be emphasized that the advantage of B cannot be fully exploited at 500 °C, and this phenomenon is inferred to be due to the insufficient fluidity of the amorphous borosilicate in the oxide scale.

At 600 °C, the evaporation rate for MoO3 increases exponentially [19] and the low intensity of the characteristic diffraction peaks of MoO3 in Fig. 3 qualitatively indicates that a small amount of MoO3 remains in the oxide scale, compared to 500 °C. Therefore, the mechanical impedance effect of MoO3 on the flow of the borosilicate is significantly decreased at 600 °C due to the evaporation of MoO3, so that the amorphous borosilicate may flow with the fluidity that is ~ 3 orders of magnitude higher than that at 500 °C to quickly form a continuous, dense and protective scale (Fig. 8) and heal the defects that remain after the removal of MoO3. Once this protective scale covers the sample surface, the inward diffusion of oxygen in the protective scale and the oxidation of MoSi2 are strongly restrained. Therefore, the oxidation and growth of the scale are very slow, resulting in the thickness increase of approximately one-tenth (Figs. 5 and 8) and in the mass gain of one-third (Fig. 2a, b) at 500 °C for the corresponding samples. Thus, the three samples show better oxidation resistance at 600 °C than at 500 °C.

We point out that while a lower viscosity of the borosilicate is beneficial for the short incubation stage of the formation of a continuously protective borosilicate layer, it also implies a faster transport of oxygen from the atmosphere through the borosilicate layer toward the substrate, i.e., more oxygen atoms reach the substrate for the sample with higher B content. Subsequently, the Mo–52Si–15B alloy showed the poorest oxidation resistance among the three samples at 600 °C.

Conclusions

-

(1)

The Mo–52Si–15B, Mo–57Si–10B and Mo–52Si–5B samples fabricated by SPS using fine alloy powders consisted of MoSi2, Mo5Si3/Mo2B5, MoB and SiO2 phases, while the SiO2 phase was introduced during the SPS process.

-

(2)

The oxidation kinetics curves and the time dependence of the mass gain, of the samples obtained by SPS and isothermally oxidized in air at 500 °C and 600 °C for 100 h, exhibited a parabolic law, while the “pest” failure was strongly suppressed. At 500 °C, the oxidation resistance increased as the nominal B content increased from 5 to 15 at%, whereas the opposite effect was observed at 600 °C. For each sample, the mass gain of the samples oxidized at 600 °C for 100 h was considerably smaller than that of the corresponding samples oxidized at 500 °C for 100 h.

-

(3)

At 500 °C and 600 °C, the oxide scale on the sample surface consists of the MoO3, amorphous borosilicate and crystalloid SiO2 phases. The oxide scale formed at 500 °C showed a thicker and fluffy morphology with defects, when the oxidation temperature increased up to 600 °C, the oxide scale was continuous and dense, and its thickness was just one-tenth of the oxide scale formed at 500 °C.

-

(4)

The better oxidation resistance of the B-doped MoSi2 at 600 °C was attributed to the significantly lower viscosity of the amorphous borosilicate and the weak mechanical impedance effect of MoO3 on the borosilicate flow, compared to those at 500 °C. The above factors ensured the rapid formation of a continuous, dense and protective borosilicate layer on the substrate surface.

References

D. A. Bertiss, R. R. Cerchiara, E. A. Gulbransen, F. S. Pettit, and G. H. Meier, Materials Science and Engineering: A 155, 165 (1992).

P. J. Meschter, Metallurgical Transactions A 23, 1763 (1992).

T. C. Chou, and T. G. Nieh, Journal of Materials Research 8, 214 (1993).

E. Fitzer, Molybdändisilizid als hochtemperaturwerkstoff, in Proceedings of the Second Plansee Seminar (1955) pp. 56–79.

K. Yanagihara, K. Przybylski, and T. Maruyama, Oxidation of Metals 47, 277 (1997).

T. Maruyama, and K. Yanagihara, Materials Science and Engineering: A 239, 828 (1997).

C. G. McKamey, P. F. Tortorelli, and J. H. DeVan, Journal of Materials Research 7, 2747 (1992).

J. H. Westbrook, and D. L. Wood, Journal of Nuclear Materials 12, 208 (1964).

K. Hansson, M. Halvarsson, J. E. Tang et al. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 24, 3559 (2004).

H. Yokota, T. Kudoh, and T. Suzuki, Surface & Coatings Technology 169, 171 (2003).

J. S. Park, R. Sakidja, and J. H. Perepezko, Scripta Materialia 46, 765 (2002).

A. Lange, M. Heilmaier, T. A. Sossamann, and J. H. Perepezko, Surface & Coatings Technology 266, 57 (2015).

M. Yan, J. Macchesney, S. Nagel, and W. Rhodes, Journal Materials Science 15, 1371 (1980).

B. Cockeram, and R. Rapp, Materials Science and Engineering A 192, 980 (1995).

K. Natesan, and S. C. Deevi, Intermetallics 8, 1147 (2000).

K. Kurokawa, H. Houzumi, I. Saeki et al., Materials Science and Engineering A 261, 292 (1999).

S. Knittel, S. Mathieu, and M. Vilasi, Intermetallics 18, 2267 (2010).

A. Lange, and R. Braun, Corrosion Science 84, 74 (2014).

J. Chen, C. Li, Z. Fu et al., Materials Science and Engineering A 261, 239 (1999).

F. Zhang, L. Zhang, A. Shan et al., Intermetallics 14, 406 (2006).

S. H. Wen, C. G. Zhou, and J. B. Sha, Corrosion Science 127, 175 (2017).

S. H. Wen, and J. B. Sha, Materials Characterization 139,134 (2018).

M. Akinc, M. K. Meyer, M. J. Kramer et al., Materials Science and Engineering A 261, 16 (1999).

J. Cheng, S. Yi, and J. Park, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 644, 975 (2015).

J. Pang, W. Wang, and C. Zhou, Corrosion Science 105, 1 (2015).

J. Y. Wu, W. Wang, and C. G. Zhou, Corrosion Science 87, 421 (2014).

W. Wang, and C. G. Zhou, Corrosion Science 110, 114 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of P. R. China (51431003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, S.H., Sha, J.B. Improvement of “Pest” Resistance of MoSi2 Intermetallic Compound at 500 °C and 600 °C via Addition of B Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering. Oxid Met 92, 243–257 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11085-019-09932-y

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11085-019-09932-y