Abstract

We take stock of the history of the European Monetary Union and pegged exchange-rate regimes in recent decades. The post-Bretton Woods greater financial integration and under-regulated financial intermediation have increased the cost of sustaining a currency area and other forms of fixed exchange-rate regimes. Financial crises illustrated that fast-moving asymmetric financial shocks interacting with real distortions pose a grave threat to the stability of currency areas and fixed exchange-rate regimes. Members of a currency union with closer financial links may accumulate asymmetric balance-sheet exposure over time, becoming more susceptible to sudden-stop crises. In a phase of deepening financial ties, countries may end up with more correlated business cycles. Down the road, debtor countries that rely on financial inflows to fund structural imbalances may be exposed to devastating sudden-stop crises, subsequently reducing the correlation of business cycles between currency area’s members, possibly ceasing the gains from membership in a currency union. A currency union of developing countries anchored to a leading global currency stabilizes inflation at a cost of inhibiting the use of monetary policy to deal with real and financial shocks. Currency unions with low financial depth and low financial integration of its members may be more stable at a cost of inhibiting the growth of sectors depending on bank funding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 OCA and Its Challenges: Overview

The literature on Optimal Currency Area (OCA) originated more than 50 years ago by Mundell (1961), McKinnon (1963) and Kenen (1969). What started in the 1960s as an academic abstract discussion morphed in the 1990s into a passionate debate about the desirability and viability of the European Monetary Union [EMU] as an OCA. The growing consensus among economists in the 1990s was that conditions favoring keeping the national currency and exchange-rate flexibility included a low labor mobility across borders, the absence of supranational tax-cum-transfer mechanisms, a high degree of nominal rigidity in domestic prices, a low degree of openness to trade, and dissimilarities in national economic structures [see Buiter (1999)]. Accordingly, more perfect currency areas are those composed of countries where most of these conditions do not hold. Similar considerations apply to the choice of pegging the exchange rate to another currency. Applying the OCA criteria, prominent economists in the 1990s argued that the euro zone was a currency union among countries that did not meet OCA conditions [see Krugman (2012), Pisani-Ferry (2013) and Gibson et al. (2014) for updated overview and analysis of these issues]. Just before the outbreak of the euro-area crisis, Jonung and Drea (2010) celebrated the success of the Eurozone despite its critics.

Influential papers by Frankel and Rose (1997, 1998) provided a more optimistic view on the stability of currency areas, noting the endogeneity of OCA criteria. A country’s suitability for entry into a currency union depends on the intensity of trade with other potential members of the union and the extent to which domestic business cycles are correlated with those of the other countries. Using 30 years of data for 20 industrialized countries, they uncovered strong empirical findings: countries with closer trade links tend to have more tightly correlated business cycles. The authors concluded that countries are more likely to satisfy the criteria for entry into a currency union after taking steps toward economic integration rather than before. This provided an optimistic avenue for the viability of “moving closer towards a more perfect union.”Footnote 1

This paper takes stock of the history of the euro zone and pegged exchange-rate regimes in recent decades, pointing out the need to reshape OCA criteria into the twenty-first century. While the contributions of the 1960s remain relevant, they were written during the Bretton Woods system when financial integration among countries and private financial flows were low and banks were heavily regulated. Thus, the discussion in the 1960s overlooked possible challenges to the stability of OCA when countries are financially integrated, cross-border financial flows are free from impediments, financial intermediation is deregulated, and there is growing depth of the “shadow banking” that competes with Main Street banks. This paper points out that greater financial integration and under-regulated financial intermediation increase the cost of joining a currency area as well as adopting other forms of fixed-exchange rate [e.g., currency board, dollarization, and the like].

A key lesson of the euro zone crisis and the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008–2009 is that fast-moving asymmetric financial shocks interacting with real distortions pose a grave threat to the stability of currency unions. Currency unions that may survive differential growth trends in the absence of financial integration among its members may find that sudden stops of financial flows sharply reduce the growth of indebted members that fund imbalances by financial inflows, ending with banking and sovereign crises. Thus, the odds of a successful currency area depend on the viability of effective institutions and policies dealing with adjustment to asymmetric financial and real shocks that impact its members. In the absence of these arrangements, adverse asymmetric-financial shocks may magnify real distortions into destructive banking, sovereign, and private debt crises, thus destabilizing currency unions. Our discussion suggests that the net benefits of joining a currency area change over time. What may have seemed like a viable and successful currency union destined to “live together happily ever after” (the first euro decade) may have turned into a bad union with strong centrifugal forces at times of asymmetric shocks that test the union’s viability (the second euro decade). Tighter unions may offer enough pooling mechanisms that provide sufficient insurance to increase the stability of a union. Achieving a tighter union, however, may require overcoming coordination problems, a move toward a banking union, possible union-wide deposit insurance backed by union-wide backstop mechanisms, and effective institutions to deal with the resultant moral hazard challenges (De Grauwe (2011), Krugman (2012), Aizenman (2015)).

A currency union of developing countries anchored to a global stable currency provides a nominal anchor, thus preventing runaway inflation [see the experience of the CFA franc]. However, such a currency union also implies the inability to use monetary policy to deal with a real and financial crisis impacting union members as well with external shocks that change the exchange rates between global currencies. Unions with low financial depth and low financial member integration may face complex dynamic challenges. Limited finance may reduce the exposure to asymmetric financial shocks threatening the stability of a currency union at a cost of inhibiting the growth of sectors that depend on external funding. Similar challenges are posed to the stability of fixed-exchange rate regimes at times of deeper financial integration [e.g., currency boards, dollarization, and the like].

2 Recent Experience with Currency Areas and Fixed-Exchange Rates Regimes: Challenged by Volatility and Financial Shocks

A manifestation of the challenges posed by financial integration to the stability of fixed- exchange rate regimes goes back to the 1990s. Emerging markets that liberalized their financial systems in the early 1990s under a fixed exchange rate experienced a rise in financial inflows that correlated with deteriorating current account deficits, real appreciation, and a heating economy. The resultant balance-sheet exposures were below the radar screens of markets and policymakers, especially when such exposures were the outcome of private borrowing. This happy-go-lucky process lasted several years until an abrupt stop of financial inflows, which was followed by capital flight crises (Calvo and Reinhart 1999). The experience of Mexico in the Tequila crisis of 1994–1995, Korea and several East Asian countries in the East Asian 1997–1998 crisis, Brazil and Russia during 1998, and Argentina in 2001 among others, followed a common pattern. The sudden stop of financial flows and capital flight triggered a balance of payment crisis, a sharp depreciation, switches to a flexible exchange rate coupled often with domestic banking crises and an IMF-type stabilization program.

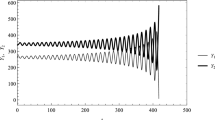

The emerging-market economic crises of the 1990s are manifestations of Mundell’s trilemma: arbitrage forces imply that greater financial openness and proactive monetary policy are incompatible with a fixed-exchange rate regime. We summarize these trends by tracking each country’s three “trilemma policy goals indexes” on zero-to-one scales -- monetary independence, exchange rate stability, and financial integration. For each of these indexes, higher value indicates getting closer to the corresponding trilemma policy goal. Fig. 1 shows the paths of the average trilemma indexes for the group of emerging markets [EMG]Footnote 2.

Towards the end of the Bretton Woods era, emerging markets exhibited a high degree of exchange rate stability, an intermediate degree of monetary independence, and a low degree of financial integration [0.9, 0.5, 0.3 in a scale of zero to one in 1970, respectively, see Figure 1]. By 2000, after the 1990s wave of financial liberalizations and sudden stop financial crises, emerging markets moved toward the middle ground of the trilemma configuration – reflected by controlled financial openness and exchange rate flexibility as well as proactive monetary policy [values of around 0.5 in a scale of 0 to 1 for the three trilemma indexes in 2000, Figure 1]. Aizenman, Chinn and Ito (Aizenman et al. 2010, 2011) tested and validated a continuous version of Mundell’s Trilemma – a rise in one trilemma variable results in a drop of a linear weighted sum of the other two. Furthermore, greater exchange rate stability has been associated with greater output volatility, and the convergence of emerging market economics to the middle ground of the trilemma has been associated with lower output volatility. Remarkably, the Trilemma “middle ground configuration” of Emerging Markets passed the test of time so far, and probably helped Emerging Markets’ adjustment to the Global Financial Crisis [Aizenman and Pinto (2013)].

The common 1990s view was that these sudden-stop crises were reflective of problematic institutions—possible crony capitalism in maturing middle income countries—with no relevance to the formation of common currency areas among more advanced economies. It took another decade to show that the challenges associated with financial globalization are universal. The short history of the euro crisis vividly illustrated the concern that asymmetric financial shocks posed grave risks to common currency areas with limited depths of union-wide banking and fiscal arrangements. Observers viewed the successful convergence of most EU countries toward meeting the Maastricht treaty criteria by 1999, and the subsequent lunching of the euro and its rapid acceptance as a viable currency as steppingstones toward a stable and prosperous Europe. This was vividly reflected by the rapidly declining sovereign spreads of the Eurozone members. Intriguingly, at times of growing current account deficits in GIIPS (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain), GIIPS bond interest rates dramatically converged during the 1990s to the German rate (see Figs. 2 and 3). By 2010, the founding fathers of the eurozone took these developments as evidence dispelling the concerns of prominent economists regarding the sub- optimality of the eurozone [Jonung and Drea (2010)]. If only….

GIIPS and German Government Bond Rates. Source: ECB, Bloomberg, http://iuwest.wordpress.com/

Similar to the experience of emerging markets that liberalized financial systems in the 1990s under a fixed exchange rate, the increasing costs of the growing balance-sheet exposures associated with large external GIIPS borrowing were mostly overlooked by markets and policymakers until an abrupt stop that was followed by capital flight crises (Aizenman 2015). These dynamics reflected a fundamental problem with the pricing of sovereign risk in which the private sector, as the “interest rate taker,” overlooks the growing marginal impact of borrowing on sovereign risk, thus inducing an externality that leads to over-borrowing. This externality was probably magnified by the economic strength of the eurozone core and by moral hazard—the presumption that the growing costs of unwinding the euro would induce bailouts down the road. Chances are that the elusive “Great Moderation” did not help by masking the growing tail risks in the OECD countries. The countries joining the eurozone experienced a buoyant decade of growing optimism associated with their deepening financial integration and convergence to low inflation before a sudden stop and capital flight crisis hit the GIIPS and morphed into the eurozone crisis, raising serious doubts about the future viability of the euro project as well as the EU.

The euro crisis revealed the inherent fragility associated with the position of a small economy in the common currency area as articulated by De Grauwe (2011): “When entering a monetary union, member countries change the nature of their sovereign debt in a fundamental way; i.e. they cease to have control over the currency in which their debt is issued. As a result, financial markets can force these countries’ sovereigns into default. In this sense, member countries of a monetary union are downgraded to the status of emerging economies. This makes the monetary union fragile and vulnerable to changing market sentiments. It also makes it possible that self-fulfilling multiple equilibria arise.” Specifically, the absence of a credible deposit-insurance scheme supported by the central bank or the federal center of a currency union implies that heightened sovereign spreads of a member country may put a self-fulfilling run in motion. This applies especially in countries with high bank-sovereign interdependence in which private banks hold large shares of sovereign debt [as was the case in the eurozone]. In the absence of a credible backstop scheme, heightened sovereign spreads may put a run in motion on the banking system of the affected country/ies.Footnote 3

Furthermore, as many insurance companies across the eurozone invested in GIIPS sovereign debt, higher sovereign spreads may have destabilized the insurance market and the entire shadow eurozone banking system. These spillovers led to adverse externalities that further destabilized the system and imposed major challenges on regulators. After a decade of large external borrowing by the GIIPS, as well as co-financing booming real estate and consumption growth, the sudden stop of financial inflows forced an abrupt end to the earlier boom. The private sector was forced into massive deleveraging, a sharp contraction in demand associated with shrinking current account deficits, collapsing real estate valuation, and ultimately bailouts by the “troika”—the EC, ECB, and the IMF. Losses of the private banking system were frequently socialized, thus massively increasing the public debt/GDP ratio.

In similar circumstances, countries with a national currency adjust by large depreciations, facilitating a painful but fast adjustment and thereby mitigating the recessionary effects of banking crises [see the experience of the U.K. and Iceland during and after the GFC, or the earlier experience of Mexico from 1995 to 1998, and Korea from 1997 to 2000]. In contrast, the GIIPS found that the rapid rise of their sovereign spreads was magnified by nominal wage and price rigidities into a deeper real crisis that induced deflationary dynamics, a rapid increase of unemployment, and an out-migration of the more movable parts of their labor force, namely, the better educated and younger workers. In line with Fisher’s debt deflation dynamics, the slow internal depreciation magnified the debt overhang and deepened the recession. These dynamics vividly illustrated the challenges facing countries in a currency union with a weak center in the presence of financial integration, under-regulated financial intermediation, and financial flows.

A lesson from the eurozone crisis is that in a shallow currency union with limited union- wide backstop institutions, adverse asymmetric financial shock amplifies existing financial and real distortions. This process may rapidly accelerate into a debt and banking crises in the affected countries, triggering a much deeper recession than one experienced under similar financial shock by a country with a stand-alone currency.Footnote 4 The contrast between the U.K. and Spain (De Grauwe (2011)), or Poland and Spain (see Figure 4) vividly illustrates the extra burden associated with being in the eurozone. The figure documents the remarkable resilience of Poland. Poland managed a steady and positive real GDP growth rate under a flexible exchange rate during the.

2000s, and thus experienced a much milder exposure to the global financial crisis and the eurozone crisis than Spain.Footnote 5 Note also the sharp V-shape recovery of the U.K. during the GFC which then resumed positive growth in less than two years. In contrast, it took Spain five years to resume positive, though anemic, growth.Footnote 6 The rise in the sovereign spread facing Spain, and the accumulation of non-preforming loans following the burst of the construction bubble, resulted in a banking crisis. By June 2012, the banking crisis induced Madrid to request international aid for its banks. Although the ECB’s three-year Long Term Refinancing Operation (LTRO) provided significant temporary relief, it also increased the interconnectedness between 12 Spanish banks and the sovereign [IMF Country Report No. 12/137]. This de-facto bailout prevented the collapse of Spain’s banking system, however, it did not avert the deepening recession.

3 Concluding Remarks -- OCA: Proceed with Caution

Arguably, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) illustrated that the endogeneity of the OCA is time dependent and differs between trade and financial integration. Common currency area members with close financial links may accumulate asymmetric balance-sheet exposure over time, thus becoming more susceptible to sudden-stop crises. This may generate asymmetric dynamic patterns in currency unions—in the phase of deepening financial ties, countries may end up with more correlated business cycles and deeper trade among its members. Once bad shocks strike and lead to capital flight from indebted countries, debtor countries that rely on financial inflows to fund structural imbalances may be exposed to devastating sudden-stop crises that reduce the correlation of business cycles between debtors and creditors union’s members countries. In a shallow currency union, debtors countries may find that fast-moving financial crises magnify the cost of real distortions, reversing the earlier gains associated with joining the currency union to costly protracted recessions associated with sovereign debt, public debt, and banking crises. The asymmetry between the impacts of deeper trade versus deeper financial integration on the stability of a currency union is rooted in the difference between temporal trade [export and imports of goods] versus inter-temporal trade [debt and portfolio flows]. Unlike commercial trade, inter-temporal trade of financial assets may lead to growing exposure to abrupt reversal of flows over time, thus testing the viability of a shallow currency area.

The net benefits of joining a currency area change over time. What seemed a viable and successful union may turn into a bad union with strong centrifugal forces at times of asymmetric shocks, thus testing the viability of the union. Tighter currency unions may provide enough pooling mechanisms to provide insurance and increase the stability of a union. However, achieving a tighter union may require moving towards banking unions, possible union-wide deposit insurance backed by union-wide fiscal mechanisms, and effective institutions dealing with the resultant moral hazard challenges. Dealing properly with these issues may require overcoming coordination failures and ‘tragedy of the common’ issues. It also may require leadership of the union core [Germany in the EMU?] and a costly learning by doing associated with experimenting various forms of backstop-mechanism [Aizenman (2015)].

A union of developing countries anchored to a global stable currency prevents runaway inflation [e.g., the CFA franc]. However, it also implies the inability to use monetary policy to deal with asymmetric real and financial shocks impacting the union (e.g., in terms of trade shocks affecting countries in differential ways) as well as with external shocks that change the exchange rates between global currencies (e.g., the appreciation or depreciation of the dollar against most other global currencies). Currency unions with low financial depth and low financial integration among its members may face complex dynamic challenges. Limited finance may reduce the exposure to asymmetric financial shocks, thereby stabilizing a currency union, at a cost of inhibiting the growth of sectors that depend on external funding. A currency union member country blessed with exportable commodities may find that union membership inhibits diversification toward manufacturing and magnifies the impact of “Dutch Disease” concerns over time, thus hindering the adjustment to terms of trade shocks. Similar concerns apply to other versions of fixed exchange rates [e.g., currency board, dollarization, and the like].Footnote 7

Notes

Glick and Rose (2002) also supported this argument, finding a large impact on the growth of trade of a currency union among its members. Revisiting this issue, Glick and Rose (2015) found a more modest impact of the EMU on trade among its members and noted that switches and reversals across methodologies do not make allowances for any bold statements. Rose (2017) provides an update of the empirical evidence.

Aizenmanet al. (2010) quantified the three-trilemma indexes for more than 170 countries during recent decades. The monetary independence index depends negatively on the correlation of a country’s interest rates with the base country’s interest rate, the exchange rate stability index depends negatively on exchange rate volatility, and the degree of financial integration is the Chinn-Ito capital controls index. For further details, see http://web.pdx.edu/~ito/trilemma_indexes.htm.

Note that this argument holds only if the central bank of the country in question is credible and the sovereign issues debt that is denominated in the local currency. Clearly, these conditions would not hold for many countries, including those that experienced crises in the Eurozone.

Among the fundamental factors of each of the individual crisis countries in the Eurozone was the build-up of external and internal debts -- whether public debt, or private debt. In these circumstances, the straight-jacket imposed by the Eurozone membership precludes country specific depreciations, magnifying recessionary forces during the adjustment.

The GDP/capital growth rate decline during the GFC [2006 to 2008] was about 4% in Poland, which was half of the decline experienced by Germany and Spain. Remarkably, the public debt/GDP of Poland increased mildly from 45% in 2007 to 57% in 2013, while that of Spain almost tripled during that period, rising from 37% to 94%. The Zloty/Euro rate depreciated by 44% during the GFC [rising from 3.21 zloty/euro in 6/30/2008 to 4.64 zloty/euro in 2/1/2009], thus mitigating the recessionary impact of the crisis. These considerations are reflected in the attitude of Beata Szydlo, the new Polish Premier elected in 2015, who described the euro as a bad idea that would make Poland a “second Greece.” [Financial Times, “ECB alarmed at UK push to rebrand Union” 12/5/2015].

The U.K.’s expansionary monetary policy induced the depreciation of the British pound by a third of its value (from 2.1 dollar/lb in Nov. 7, 2007, to 1.38 dollar/lb in January 22, 2009), thus facilitating a faster recovery. In contrast, Spain stagnated. The sharp increase in the sovereign spread of Spain in 2010 and 2011 and its stagnating growth implied that, despite entering the crisis with lower public debt/GDP than the U.K., Spain resumed anemic growth in 2014 with a sizably larger public debt/GDP than the U.K.

Kazakhstan’s fixed exchange rate regime was one of the latest victims of the declining commodity prices, moving to a floating exchange rate in August 2015. Plummeting oil prices and devaluations by Russia and China increased exponentially the cost of defending the currency against the dollar. Azerbaijan followed Kazakhstan in moving to a floating currency in December 2015, after a devaluation of about 25% in February 2015. In both cases, growing exchange market pressure and declining international reserves induced exchange rate regime changes.

References

Aizenman J, Chinn MD, Ito H (2010) The emerging global financial architecture: Tracing and evaluating new patterns of the trilemma configuration. J Int Money Financ 29(4):615–641

Aizenman J, Chinn MD, Ito H (2011) Surfing the waves of globalization: Asia and financial globalization in the context of the trilemma. J Jap Int Econ 25.33:290–320 September

Aizenman J, Pinto B (2013) Managing Financial Integration and Capital Mobility—Policy lessons from the past two decades. Rev Int Econ 21(4):636–653

Aizenman J (2015) The Eurocrisis: Muddling through, or on the Way to a More Perfect Euro Union. Comp Econ Stud 57:205–221

Buiter W (1999) The EMU and the NAMU: What is the Case for North American Monetary Union? Can Publ Policy 25:285–305

Calvo, Guillermo A., and Carmen M. Reinhart. "When capital inflows come to a sudden stop: consequences and policy options." (1999)

De Grauwe, Paul, " The Governance of a Fragile Eurozone ," (2011), CEPS Working Documents, May

Frankel JA, Rose AK (1997) Is EMU more justifiable ex post than ex ante? Eur Econ Rev 41(3):753–760

Frankel JA, Rose AK (1998) The endogenity of the optimum currency area criteria. Econ J 108(449):1009–1025

Gibson HD, Palivos T, Tavlas GS (2014) The crisis in the Euro area: an analytic overview. J Macroecon 39:233–239

Glick, Reuven and Andrew K. Rose. “Currency Unions and Trade: A Post-EMU Mea Culpa”, (2015), CEPR Discussion Paper 10615

Glick R, Rose AK (2002) Does a currency union affect trade? The time-series evidence. Eur Econ Rev 46(6):1125–1151

Jonung, Lars, and Eoin Drea. "It can’t happen, it’s a bad idea, it won’t last: US economists on the EMU and the Euro, 1989–2002." Econ Journal Watch7.1 (2010): 4–52

Kenen P (1969) The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas: An Eclectic View. In: Mundell R, Swoboda A (eds) Monetary Problems in the International Economy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Krugman P (2012) Revenge of the optimum currency area. NBER Macroecon Annu 27(1):439–448

Mckinnon R (1963) Optimum Currency Areas. Am Econ Rev 53:717–725

Mundell R (1961) A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas. Am Econ Rev 51:657–675

Pisani-Ferry J (2013) The known unknowns and unknown unknowns of European Monetary Union. J Int Money Financ 34:6–14

Rose AK (2017) Why do Estimates of the EMU Effect on Trade Vary so Much? Open Econ Rev 28(1, (2017)):1–18

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the discussion and comments at the March 8-9 2016 ATI-IMF seminar on “The Future of Monetary Integration,” Mauritius, and the insightful comments of George Tavlas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aizenman, J. Optimal Currency Area: A twentieth Century Idea for the twenty-first Century?. Open Econ Rev 29, 373–382 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9455-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9455-y