Abstract

The 20th century witnessed two Chinese translation booms of the Hungarian writer Mór Jókai’s work. In order to have a better understanding of Jókai in China, this paper focuses on the Chinese translation of Jókai’s work, providing an overview of its history, and offers insights into the socio-cultural context of the translation, the features of Jókai’s writing highlighted in translation, and the Chinese understanding of his literary world. It will be shown that the Chinese translation of Jókai’s work in the 20th century was almost always dominated by political discourse: in the early 20th century it was “the literature of marginalized nationalities,” and in the second half of the century “the literature of socialist countries.” While the readers in the earlier period inserted modern China’s national consciousness into their interpretation of the writer, who therefore appeared as strangely familiar to them, the readers in the later period were under the influence of socialist ideology, thus distinguishing themselves from the writer, who was regarded as a bourgeois novelist. For the latter, they not only constantly warned themselves of his idealist parochialism but also thought of him as a tragic Rousseau/Owen-style utopian.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

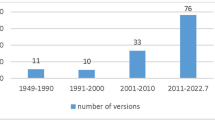

As an influential nineteenth-century Hungarian prose writer who has gained worldwide recognition, Mór Jókai (1825–1904) began to be introduced to Chinese readers in the early 20th century, and two periods can be distinguished in terms of the Chinese translation of the writer’s work. First, two novels were translated into classical Chinese in the 1900–10s, followed by the translation of several short stories into traditional, vernacular Chinese in the 1930s. Six other novels and two short story collections (partly overlapping) were translated into simplified, vernacular Chinese in the 1980–90s. During the long interval between the two waves, only two translations (including one re-translation) were published. The Chinese translations of Jókai’s work in the 20th century were initially carried out by influential Chinese writers, and only later by professional translators, who by and large never tried to make their translation appear purely cultural and literary exchange between countries, but regarded it as a cultural and literary response to certain social needs and political discourses. As Jókai’s first readers, they actively undertook the task of introducing him to the Chinese audience. As a consequence, the Chinese understanding of Jókai was largely founded upon an image shaped by those writers and translators, and their ideas about the author formed the central part of his reception in China. In general, the reception of Jókai in China in the 20th century had been inextricably linked to political discourse. In the first half of the century, when national consciousness was on the rise in modern China, Jókai’s work was closely attached to the politicized literary discourse of “the literature of marginalized nationalities.” At that time, Jókai was perceived by Chinese readers as a compatriot from a distant continent, giving them a sense of both strangeness and familiarity. In the second half, however, the dissemination of Jókai in China took place in the context of socialism, and the translation of his works took on the character of serving a socialist form of consciousness. At this time, Jókai’s work was more criticised than praised, as he was regarded as one of the spokespersons of bourgeois fiction for Chinese readers.

Jókai’s Chinese translation in the first half of the 20th century occurred against a highly politicized backdrop, when China was experiencing unprecedented turbulence and change in its efforts to establish a modern nation state. At that time, its internal and external crises gave rise to modern nationalist thinking; the forerunners of Chinese nationalism considered the world to be divided between the powerful and the marginalized nations,Footnote 1 with China belonging to the latter. Correspondingly, in the literary field the division between Western (powerful) literature and that of marginalized nationalities also arose, with nationalist thoughts taking the cultural high ground.Footnote 2 The successive occurrence of the New Culture MovementFootnote 3 and the May Fourth MovementFootnote 4 was a clear manifestation of the trend towards the close integration of literature and culture with politics. While the former promoted the introduction of foreign (especially Western) culture and literature to China, the latter attached a strong political motive to it. On one hand, numerous literatures of Western powers, e.g. British, French and German, were translated and introduced to the Chinese audience with the aim of learning from the strong; on the other hand, the translation of the literature of marginalized nationalities became prevalent as the proponents of modernization realized that it was necessary to seek for affiliation with those who had been or were under oppression. This consequently “created a pluralistic situation in the selection of foreign literature to be translated” with “political needs as the dominant motive” (Xie & Zha, 2003, p. 22–23).Footnote 5 Jókai, along with Hungarian literature, or more broadly, East-European literature, was introduced as literature of marginalized nationalities.

A rather broad picture of Jókai was formed in Chinese context when the novelist was intensively translated and introduced during the period of 1900–1930s.Footnote 6 Two novels and one feuilleton story were firstly translated from their English versions. There Is Only One God was published by the Commercial Press in 1909 as one of the volumes in the “Shuobu Series,” and reprinted in 1933 in the “Wangyou Series” edited by Yunwu Wang. It must have been translated from Percy Favor Bicknell’s American translation called Manasseh (1901), with the original Hungarian title—Egy az Isten—appearing on the cover. Surprisingly, the Chinese translation made a mistake on the issue of the English translation: “its original title meant There Is Only One God (Egy az Isten); in the English version the title was changed into Midst the Wild Carpathians”Footnote 7 (Zhou, 1935, p. 4). While the reason for this mistake remains a mystery,Footnote 8Midst the Wild Carpathians (1894) is actually the title of R. Nisbet Bain’s English translation of Erdély aranykora [The Golden Age of Transylvania]— another novel by Jókai. The Yellow Rose was translated in 1910 from Beatrice Danford’s American translation, then introduced to the Commercial Press by Yuanpei Cai in 1920 and finally published in 1927. “Love and the Little Dog” was made from Bain’s translation (in Tales from Jókai, 1904) and collected in the second volume of Diandi [Drops] (1920)—a short story collection of Zuoren Zhou’s translations from literatures of Russia, East and North Europe, Greece, South Africa and Japan. An essay entitled “Yuke Moer Zhuan”Footnote 9 [Biography of Mór Jókai] was written in 1910, which provided a thorough review of the writer and his work. As well as indirect translation via English, quite a few translations of Jókai’s work were made from Esperanto, i.e. “Pola Rakonto” [A Polish story], “La Edzino de l’ Falinto” [The wife of the fallen soldier], and “Kiunella Sep” [The cobbler],Footnote 10 which, along with three Bulgarian and two Czech stories, were collected in a book called Pola Rakonto (Zhong in Jókai, 1934). In addition to those published translations, there were some supposed to be published but never done, e.g. two previewed short stories at the end of the first volume of Yuwai Xiaoshuoji [A Collection of Foreign Stories] (1909) translated jointly by Zhou and his elder brother Lu Xun. Bain’s English translation of Tales from Jókai and Halil the Pedlar, and Sarah Elisabeth Boggs’s American translation of Told by the Death’s Head were already among Chinese literati’s bucket list.

Under the political discourse of the literature of marginalized nationalities, Jókai appeared as both alien and familiar in the Chinese context: the importance of his romantic writing was downplayed, while much attention was aroused by his nationalist agenda. The ideas of such critics as Emil Reich,Footnote 11 Nisbet Bain, and Frigyes RiedlFootnote 12 helped the formation of Chinese views on the writer, as can be glimpsed from the Chinese biography of Jókai, where a fusion of their perspectives can be seen, with a note added to the end: “This paper is a record of Bain’s biography and an adoption of the two literary historians’ words” (Zhou, 2009, p. 299). Like Bain and Riedl, Zhou located the novelist in romance writing, especially historical romance, with a curious and alienated eye. As his most ardent English translator, Bain successfully inserted the writer as a romancer with humor into the readers’ mind: “Jókai is one of the greatest tale-tellers of the century. Moreover, there is a healthy, bracing, optimistic tone about his romances which appeals irresistibly to normal English taste” (Bain, 1904, p. 57). But he also admitted that the writer belonged to “the old school” in a time when “the fashion of modern fiction has changed” and when the readers preferred “documents” or “studies” to “tales” or “yarns.” (Ibid.) Riedl shared Bain’ opinion. On the one hand, he agreed on “his wonderful power of invention,” “his sparkling vivacity and fluency,” “his humour which was [...] gay and agreeable” and “a vivid imagination” to the extent that he asserted that “there has not been a more brilliant narrator since the time of the Arabian Nights” (Riedl, 1906, p. 185). On the other hand, he was critical of the writer’s superficiality and lack of knowledge of human nature in his narrative (Ibid.). Based on the two critics’ comments, Zhou developed a curiosity about Jokai’s tale-telling creativity, but added that he had the common defect of the romantic school that he could not look into men’s hearts like the later writers (that he could not look into men’s hearts like the later writers (Zhou, 2009, p. 209). “The later writers” here must refer to the realists, the naturalists and even the modernists, who were the mainstays of Western literature in the late 19th century and the early 20th century. These were greatly admired by the Chinese as a consequence of the New Culture (Literature) Movement, which was more interested in realistic than romantic writing, partly because the latter might have reminded them of classical Chinese novels which often showed similarity to romance. A conteur par excellence of the romantic school, as they called him, Jókai was read as an unique or even anachronistic phenomenon among modern novelists in either English or Chinese context. From this point of view, Zhou, and other Chinese readers, must have sensed a strong strangeness and novelty in Jókai; his works were often labeled as “strange” and “unfamiliar,” always arousing an interest in reading (Zhou, 1935, p. 7; 1982, p. 200).

Influenced by Reich, Zhou inserted a nationalistic reading of Jókai into Chinese context by asserting the link between the writer and his nation. Reich emphasized him as the national image of Hungary:

Nearly everything has changed in Hungary during the last forty years; but the love and admiration for the genius of Jókai had never suffered diminution. In his checkered life there is not a blot, and in his long career there is not a single dark spot. Pure, manly, upright as a patriot, faithful and loving as a husband, loyal as a subject, kind as a patron, an indefatigable worker, and, highest of all, a true friend both to men, fatherland, and literature, he had given his nation not only great literary works to gladden and enlighten them, but also a sterling example of Magyar virtue and Magyar honour (Reich, 1898, pp. 226–227).

This passage, quoted in full by the translator (Zhou, 2009, p. 209), is a typical nationalist interpretation of literary writing, in which Jókai is regarded as a typical Magyar writing for Magyar people—a spokesman for Hungary. This is based on Reich’s wish that the book should “contribute somewhat to increase the interest of the great British nation in a nation much less numerous but in many ways akin” (Reich, 1898, p. 2). The word “akin” discloses the other half of the story: Reich’s aim is to find echoes outside Hungary, so as to position Hungarian literature within Europe or even the world, and through comparisons to present Magyar literature as already familiar:

By introducing the comparative method of historical investigation and analysis, by means of which Hungarian works are measured, contrasted to, or compared with works of English, French, German, Italian or the ancient classical writers, the reader may obtain, it is hoped, a more life-like idea of a literature hitherto unknown to him (p. 1).

This is an attempt at networking Hungarian literature with that of other countries, a modern consciousness of introducing the national to the world. Reich’s ideas were in line with the Chinese need to make heard a literary voice in the world, i.e., forming a modern Chinese literature, and therefore they were welcome in China to the extent that his book remained a favorite even after the publication of Riedl’s work.Footnote 13

The translation of There Is Only One God was a consequence of nationalistic reading; the novel therefore appeared as a historical novel about a marginalized nationality previously unknown to China. The story starts with the love story between Manasseh and Blanka in Italy, followed by their adventurous journey back to Transylvania, and then the self-defense war of the Szeklers against the invaders (Jókai 1933). Its romantic elements were well captured: “It is sprinkled with love affairs and politics, interesting indeed” (Zhou, 1982, p. 200). But what appeared more attractive in Chinese context was the historical rather than the romantic part. The novel touched one of the most fascinating topics: the Huns, through whom Chinese readers might best be able to find an affinity with Hungary. The Chinese firmly believed that the Huns, whom the Hungarians claimed as their ancestors, were the descendants of Xiongnu, a nomadic tribe on the northern borders of ancient China around the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE.Footnote 14 As Zhou recalled, “At that time we recognized the Hungarians as the yellow race [...] how could this not interest us in an era (thirty years ago) when nationalism was prevalent?” (2001, p. 11.) The story is mostly set in the Transylvania of the Szeklers, who claim the ancestry of Attila the Hun, and presents the hostility between the Magyars/Szeklers and the Romanians during the Hungarian revolutionary War of 1848, which immediately aroused attention in Chinese context. The Chinese title of the book already implies a nationalistic strategy of interpretation. The de-theologized Chinese title—Xiongnu Qishilu [Heroes of the Huns]—may hint at the consideration that Chinese readers would have difficulties in understanding religious history and foreign theology. But the title promised a story about places and characters related to the Chinese. “The Hun heroes” must refer to Manasseh and his villagers, the Szeklers, who fight against the combined invaders supported by the government of Vienna, hence the representatives of nationalism. From this viewpoint, the novel functioned as the cultural exchange between the two marginalized countries by providing Chinese readers with the possibility of historical bond with a foreign culture. Through Jókai, the Chinese saw the similarity between China and Hungary in terms of their national fate and suffering, and anticipated the possible social effects brought by Jókai. The prevalence of nationalist ideas therefore gave a direct impetus to the dissemination of the novel in Chinese context.

The Yellow Rose, a novella of rural setting,Footnote 15 was received in China as “one of the abiding ornaments of national literature” (Zhou, 2009, p. 208)—a sample of how to position local literature within world literature. This view is revealed by the following explanation:

two reasons can be accounted for selecting this piece from Jókai’s novels of two hundred volumes: one is its attachment to the nation and the people, the other is its artistic presentation. Its description of the nation and the people captures the picturesque portion of Hungary; its narrative is full of beauty and poetry (pp. 213–214).

The first point must refer to its presentation of local culture of Hungary, i.e., the puszta and the country folk, and the second one to its pastoral narrative, features which together were said to facilitate a poetic presentation of Hungary. On the one hand, the novel was highlighted for its form of pastoral following the idyllic tradition of ancient Greece (p. 216). As a consequence of the translation of Western classics in the early 20th century, Chinese writers was impressed by ancient Greek and Roman literature—the origin of Western literature, among which was the mode of pastoral developed from Theocritus’s Idylls into a popular genre during the Renaissance. The pastoral form attracted them to the extent that they developed a thorough study of it in the early 20th century.Footnote 16 One should not be surprised by their fondness for the pastoral genre in Western tradition; the concept of pastoral was not unfamiliar to Chinese literati since it was very close to “Tianyuan” [idyll], a school of classical Chinese poetry set up by Yuanming Tao (365–427) and influential for many centuries. Though the definitions of pastoral in the two traditions were rather different, they both implied a longing for a simple and idealized life. The novel in the Chinese context was interpreted as a typical pastoral piece: “Jókai absorbs the pastoral tradition of Theocritus and Longos to present one of the most natural narratives [... to the extent that] it is very possible to make this prose into poetry.” (p. 212) Jókai’s literary genealogy was traced to the ancient Greek and Roman origin, and he was located in the literary system of Western/European literature. This shows a panoramic view of Jókai and Hungarian literature from Chinese perspective: though being that of the marginalized nationalities, Hungarian literature shared the same literary tradition with the literature of Western powers such as British, French and German. This perspective of literary history, probably due to the influence of Reich, is largely revealed in the following passage by Zhou:

The trend of Hungarian prose was in line with Western European literature. Jókai was preceded by Kármán (1763–1845) who wrote Fanni hagyományai, a love proseFootnote 17 inspired by Richardson’s Pamela and Goethe’s Werther, Jósika (1794–1865) who wrote historical novels by imitating W. Scott, and Eötvös (1813–1871) who, while immersing himself into politics, wrote poetry and prose, among which A falu jegyzője was the best. After Jókai, more and more prose writers emerged in Hungary, with Mikszáth as one of the representatives (p. 214).

It is clear that Chinese literati were not only interested in Jókai, but also eager to see a broader picture of Hungarian literature or even world literature by way of the writer, which reflects China’s modern literary consciousness of seeking for networking with world literature and positioning Chinese literature within the world.

On the other hand, in the Chinese context much attention was aroused by Jókai’s presentation of peasant life on the Great Hungarian Plain in the novella, hence the comment of “a contemporary masterpiece of Xiangtu literature” (p. 217). “Xiangtu” means “land of home,” “native-soil” or “homeland”; Xiangtu literature therefore refers to the literature articulating local life of certain place, or homeland, and containing various local elements and colors. With its focus on the writer’s homeland, the novel was read as a typical piece of Xiangtu literature. As Zhou put it,

Jókai was born in the romantic times when it was common to write about homesickness and nostalgia for the past; having lingered long on the historical issues, he wrote this as a memorial to his homeland. Although its source is the mode of pastoral, its depiction of the nature—a combination of idealistic and realistic ways—goes beyond that of the ancients, making it a contemporary masterpiece of Xiangtu literature. (Ibid.)

This was the first appearance in the Chinese context of the term, which subsequently became an important genre in the formation of a modern Chinese literature. Jókai’s writing therefore contributed to the Chinese development of their own literary discourse of Xiangtu literature, with Zhou, the translator, as one of the pioneers,Footnote 18 with local color, natural beauty, and folk customs in its theoretical core.Footnote 19 Clearly enough, the concept of Xiangtu literature was a proto-national or quasi-national literary term since it emphasized the presentation of national character through literature and always showed the inclination to present the most local elements to the world. In this interpretation, the novel was not just a piece of pastoral, but a Hungarian variation of the pastoral tradition, in which the Hungarian landscape could be faithfully presented. The story unfolded in the Hortobágy,Footnote 20 and the novel was thus regarded as an ode to the beauty of Hungary:

The Alföld in the book is where the Magyar, the main population of Hungary, originally lived, and refers to the large plains between the Tisza and the Danube. The Tisza is to Hungary as the Volga is to Russia, and has inspired numerous literati from the past to the present. By the Tisza is the Hortobágy, where the most remarkable natural scenery and folk customs can be seen. Jókai in his youth stayed there long and formed a vivid picture of it in his mind. (Ibid.)

In other words, Jókai was believed to have presented a typical Hungarian story impossible to find elsewhere, through the category of Xiangtu literature, in which the local life of Hungary was portrayed.

A particular interest in such typical images on the Great Plain as the cow-herds and the horse-herds was also formed in the Chinese context due to the belief that they symbolized the Hungarian nation. Jókai wrote: “Certainly there are plenty of thieves among the shepherds, and some of the swineherds turn brigands. [...] Just as counts and barons are among grand folk, so are csikós and cowboys among the other herdsmen” (1927, pp. 25–26). Descriptions of this type were not only highlighted by Chinese reading but also seen as the best reproduction of what Reich described in “Petőfi, the Incarnation of Hungary’s Poetic Genius,” a chapter in which he introduced the puszta and the people living on it from a nationalist perspective. Indeed, the Chinese view of the puszta was largely shaped by Reich’s nationalist introduction, earlier translated into Chinese by Lu Xun, which became the basis of the understanding of the Hungarian folk culture. An examination of Reich’s chapter will give the impression that the presentation of the puszta was always regarded as an exponent of the Hungarian nation: “The real relation, however, between the poet and his country is that between the traveler and the mirage. It is in the eyes of the former that the latter is forming, and there alone” (Reich, 1898, p. 177). Reich’s pages-long description of the natural scenery and folk customs on the Great Hungarian Plain was referred to in the Chinese preface of The Yellow Rose by the translator, who must have regarded it as the best piece for revealing the spiritual core of the novella: “This passage gives the most delicate portrait of Hungary’s countryside views and herding life to the extent that it can be the preface to The Yellow Rose, only through which the readers can fully understand the novel” (Zhou, 2009, p. 213). Since Reich’s nationalist portrayal had been widely recognized in the Chinese context, that Jókai’s description was connected to it indicated a positive reception of the novellas as the display of the Hungarian nation. Chinese readers saw the presentation of local culture as an effective way to write national literature. Overall, the translation of The Yellow Rose presented the Chinese consistent consideration of the relationship between national literature and world literature in the early 20th century, reflecting a modern literary consciousness within the context of modern nation building.

Those stories translated from Esperanto took on overtones of exhortation and education in the Chinese context, with the translator emphasizing the sense of nationhood on the one hand and the sense of class on the other hand. The popularity of Esperanto in China in the early 20th century was a consequence of introducing the literature of marginalized nationalities, which constituted a significant part of the New Literature Movement. Compared to a foreign language, from which translation (direct and indirect) was usually made, Esperanto, a language constructed for international communication, easy to master, was a better option for those Chinese who didn’t know other foreign languages, which often required more time and talent. In addition, the translation made from Esperanto was believed to be more faithful to the source text (Hu in Lao, 1982, p. 213).

Taking Esperanto as an ideal agency, the Chinese made numerous translations, especially of the literature of marginalized nationalities. It can be said that from the beginning, Esperanto was attributed the political aim of uniting the oppressed countries and promoting cultural exchange between marginalized nationalities, hence a manifestation of the sense of nationhood. Lu Xun’s words show the nexus between Esperanto and the grand goal of solidarity and mutual understanding: “It can unite one with another in the world, especially those under oppression; it can also help with the mutual introduction of literature between different countries; Esperantists are beyond the hypocrisy of egoists” (Lu in Lao, 1982, p. 203). The three aspects concerning Esperanto reveal the Chinese’s cultural strategy of positioning the nation in the world: looking beyond the borderline and showing interest in other marginalized nationalities and their literature. Influenced by the New Literature Movement, which preferred short stories/prose to long ones,Footnote 21 quite a few of Jókai’s short stories were translated during the 1920–1930s through Esperanto.Footnote 22 The fact that three of his short stories were put into one book together with three Bulgarian and two Czech stories indicates that the writer, along with others, was read as the literary representative of marginalized nationalities from South and East Europe. “Pola Rakonto” and “La Edzino de l’ Falinto” are based on the struggling history of two countries: the former is about Poland’s fight against Russia, the latter Hungary’s confrontation with Austria.

It is interesting to see how close was the attention paid by the Chinese audience to Polish people through Jókai. The first story sets up the heroic image of the Polish protagonist, who takes a revenge on a Russian general for his wife’s murder. Jókai’s presentation of Poland was interpreted as follows:

Jókai was a participant of the great Revolution of Hungary when Poland, a neighbor who bore no less suffering, offered their support, which helped the writer recognize the virtue of Polish people. In this story he vividly but almost exaggeratedly presented the great will of the protagonist, and at the same time described with an overstated tone the terror caused by the Russian rule. The readers should not be surprised by this because firstly, he wrote this piece when hatred of Russia became a consensus in Hungary due to the Russian invasion, and secondly, his purpose of writing was not to reproduce the reality of Poland but to describe it by departing from Hungarian imagination (Zhong in Jókai, 1934, p. 64).

The passage shows that the story was regarded as not a faithful record of Polish history but a reflection of the Hungarians’ consciousness of liberation. In other words, rather than taking this story as an opportunity to know more about Poland, another marginalized nation, Chinese readers were more invited to perceive the Hungarians’ national consciousness through their imagination of Poland. This perspective of interpretation was rooted in the context of the 1930s when modern China’s national consciousness came to peak along with the rise of left-wing literature and the tension between China and Japan, pushing Chinese readers to empathize with the display of national consciousness in Jókai—a mirror to that of the Chinese. This mode of interpretation continued in the second story “La Edzino de l’ Falinto,” in which much attention was still given to the Polish side, though the writer recounts a Hungarian legend from the 1848–49 war. Due to the mention of the Polish legion accompanying the Hungarian Revolutionary army in the story, the tie between the two countries was once again highlighted: “Poland was a friend of Hungary at that time and offered much help. About the Polish legion, i.e. the Red Cap legion in Jókai’s words, there are still legends in our century” (p. 112). The emphasis on the presence of Polish people and the friendship between Poland and Hungary recalls the Chinese scenario of uniting the oppressed to fight against the aggressor—a national consciousness containing both affinity and confrontation.

The third story “Kiunella Sep” can be interpreted as a representation of class conflict, thus reflecting the increasing modern consciousness of class issues in the first half of the twentieth century in China. It tells a story of the rich and the poor, an aristocratic bachelor occupying nine rooms upstairs and a cobbler with his nine children downstairs. A Christmas Eve feuilleton story with no lack of humor and entertainment, it has unexpectedly received particular and consistent attention in the Chinese context, becoming the writer’s most popular and best-known piece in China. Apart from Zhong’s translation, another translation was made by Kai Xiong in 1959 from the English typo-script provided by the Hungarian Embassy in China entitled “Who Is the One in Nine?” It appeared and was widely read in various magazines for middle-high school students; in the new century, it has been frequently on the reading lists of teenagers, and in 2013 was even selected as reading material for the college entrance examination of Liaoning province, the title being changed to “The Singing of Christmas Carols.”

The reason for this perpetual popularity can be found in the 1930s when it was first introduced in China. Along with the soaring national consciousness, there was the awakening of a modern class consciousness due to the Left-Wing Cultural Movement under the influence of newly imported Marxism. The confrontation between the rich and the poor, or more precisely, bourgeoisie and proletariat, began to shape the ideological form. Many saw class conflict as the main contradiction in society, with the divergence between the newly founded Communist Party and the governing Chinese Nationalist Party as the political manifestation of this class conflict. The Union of Left-Wing Writers, founded in 1930, started to advocate the translation of Marxist literary theories and the literature of the Soviet Union; with the foundation of the PRC, the emphasis on presenting class struggle had become the mainstream of literature for a certain time and still shows its influence in the new century. In this context, “Kiunella Sep” has been endowed with a great meaning of exhortation and education, due to its presentation of two different ways of life, seen as representing the opposition between the two classes. The story is rather simple: on Christmas Eve the cobbler refuses either to give his child to the landlord, who promises the child a bright future, or stop singing Christmas carols with his children when the landlord, annoyed by their singing, offers him a fortune. This theme is not uncommon in Jókai’s work as he often revealed his dislike for money-worshipping society, e.g. Az arany ember, later in his career. But it has aroused particular interest among Chinese readers:

Jókai was a sage of life. [...] He did not give us empty sermons, but made use of his role as a novelist to tell a story which reminds the readers of the wisdom of daily life. Under his pen, a poor and ordinary cobbler meets the predicament of life: he has to choose between money and family, money and joy, or deeply speaking, material desire and spiritual pursuit. He hesitates [...] and makes wrong choices in the beginning, [...] but after a while he understands that nothing in his life is more important than family, children and happiness, and therefore gives the right answer in the end, firmly and urgently. (Anonymous in Jókai, 2013, p. 32).

A passage with much philosophical color, it seemingly has nothing do to with the considerations of class. But careful examination reveals an explicit and fundamental class consciousness: there is a distinction between right and wrong, i.e., an ideological preference to proletarian people. While the cobbler, a representative of the lower class, takes a moral superiority and is transcendent enough to overcome his material desire, the landlord, a representative of the upper class with his money, appears to the Chinese gaze as an incarnation of evil. This binary opposition between the two classes and the attachment of moral judgment to them showcases a deeply rooted discourse of class running through modern Chinese history.

Jókai’s Chinese translation in the second half of the 20th century started in a very different sociopolitical and cultural context. With the founding of the People’s Republic, China embarked on the path to socialism. With socialism becoming the dominant political discourse in the society, tremendous changes happened in the cultural and literary field: artistic creation and criticism came under socialist censorship to meet political needs. Socialist literature or literature from socialist countries was welcomed while bourgeois literature or literature from capitalist countries was criticized. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that Jókai’s translation during this period was a result of the politically dominated cultural exchange between socialist countries.

An iconic event was the circulation of Géza Hegedüs’s article “Buxiu De Yuekayi Moer” [Immortal Mór Jókai] in the Chinese context. In 1954 when Hungary was commemorating the 50th anniversary of Jókai’s death, China also held commemorative events to show their respect for this famous writer from their socialist ally, including the translation of Hegedüs’s article in the state-supported journal called Yiwen [Translated Articles] edited by Mao Dun (1896–1981), one of the most prestigious modern Chinese writers. “Buxiu De Yuekayi Moer” ends with the note that “This was originally published in Issue 46 of Hungarian News, a Chinese language publication produced by the Hungarian Embassy in China” (1954, p. 106). In the translation, Hegedüs (1912–1999), a Hungarian writer and critic, appeared to have given a thorough introduction to Jókai and his work from the socialist viewpoint of criticism, where Jókai appears as: (1) a liberal; (2) a patriot; (3) a critical realist; (4) an utopian (92–106). In other words, he was believed to have emphasized the revolutionary, patriotic, realistic and idealistic side of Jókai’s writing.Footnote 23 Due to Chinese readers’ lack of access to Jókai in non-socialist contexts at that time and Hegedüs’s well-constructed ideas of the writer from the socialist perspective, catering to the expectations of the Chinese audience, the translation of his paper immediately became the encyclopedia and guideline of Jókai for Chinese readers; from the 1950s onward, all the Chinese translations were profoundly influenced by Hegedüs’s views, as shown below.

Before moving to Jókai’s Chinese translation in the 1980s, when a boom occurred, the period between 1949 and 1966Footnote 24 needs to be mentioned here, since it saw two translations (including one re-translation), heralding the intensive socialist configuration of Jókai’s translation decades later. One is For Liberty in 1956 and the other is The Yellow Rose in 1960. For Liberty can also be regarded as one of the Chinese’s commemorative events of Jókai because in the same issue of Yiwen where the translation of Hegedüs’s article was published, the story “The Szekely Mother” to be collected in the book was already translated, and in the afterword of the issue, a brief introduction to the book was already offered. In this afterword, and later on the title page of For Liberty, the source of the translation can be read: “Mór Jókai, For Liberty,Footnote 25 made from the English typo-script provided by Foreign Cultural Liaison Bureau.” Since Jókai did not write a book entitled “For Liberty,” it must be made from the English typescript of A szabadságért [For Liberty], a collectionFootnote 26 published in 1952 by Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, a publishing house run by the state in Budapest, as one volume in the series of “Szabadságharcos kiskönyvtár” [Freedom Fighter Library]:Footnote 27 the name already indicates that the series must carry the task of political propaganda. It is thus evident that For Liberty was supported by the states to be part of the cultural and literary exchange between socialist countries, with a special focus on sharing the experience of national liberation and disseminating revolutionary spirit.Footnote 28

This collection contains six short textsFootnote 29 which are exclusively about the Hungarian Revolution between 1848 and 1849, presenting the stirring patriotism and heroism of Hungarian people. Chinese readers gave a rather positive comment on its representation of the Hungarian Revolution:

Though Jókai did not write the panorama of the Hungarian Revolution, he, due to his positive participation in the Revolution and his mastery of historical materials as well as his rich imagination, was able to give vivid and impressive descriptions of some heroic scenes and events, which successfully set up the immortally heroic images of Hungarian people in the readers’ mind. This book can be regarded as a witness’s faithful record of the heroic deeds in the people’s revolution (AnonymousFootnote 30 in Jókai 1956, p. 4).

This passage shows that Jókai’s Chinese audience tended to blur the boundary between reality and fiction and believe his fiction to be faithful record of historical events. When reading the book, they must have expected to learn more about Hungarian history, especially its revolutionary history, which was one of the targets of the cultural exchanges between Hungary and China. The comment also indicates an enthusiasm about Jókai, a bourgeois revolutionary taking the side of the Hungarian people. In the book, Jókai presented many heroic characters from the lower classes, which must have impressed the Chinese due to the popularity of proletarian narrative in the socialist context.

The Yellow Rose might partially owe its Chinese popularity to some similarly interpretable features. The Yellow Rose was definitely another result of the politically oriented cultural exchange between Hungary and China; it functioned as an “open sesame” to reintroduce Jókai and his work to socialist China.Footnote 31 Though having been translated into Chinese by Zhou in the early 20th century, it was re-translated by Tang Zhen in 1960. It is not unusual to see a new translation of a book appear in every few years, but in this case, Tang’s translation obviously carried the political goal of reshaping Jókai in socialist China—a different Jókai from Zhou’s perspective. Zhou had been never really accepted by the communist regime due to his rightist views and his entanglement with Japan-supported Wang Jingwei Government during the Sino-Japanese War.Footnote 32 While his translation had been out of the mainstream favor, Tang’s translation appeared as a timely replacement, which also explains why Tang chose to translate The Yellow Rose first among Jókai’s works. Though this novel barely refers to revolutionary issues, a recollection of the Revolution was still under the Chinese scrutiny:

We are not going to stick for ever on this meadow-land. When I was a little child I saw beautiful tri-colour banners waving, and splendid Hussars dashing after them. . . . . How I envied them! . . . . Then later, I saw those same Hussars dying and wounded, and the beautiful tri-colour flag dragged through the mire, . . . . but that will not always last. There will come a day when we will bring out the old flag from under the eaves, and ride after it, brave young lads, to crack the bones of those wicked Cossacks! And you will come with me, my good old horse, at the trumpet’s callFootnote 33 (Jókai, 1960, pp. 133–134).

This is an inner monologue of the horse-herd when he feels hurt by his lover’s infidelity and spends the night alone. An explanation to “tri-colour banners/flag” was offered in the footnote to remind the readers that the protagonist still remembers the Revolution and thinks of his country at such private moments. Jókai’s presentation of rural Hungary was highlighted: “The writer describes the local customs of Hungarian people and the natural scenery on the Hungarian plains with great artistic power” (Tang in Jókai, 1960, p. 2). All these were believed to have proved Jókai’s patriotism, as the translator said, “in the descriptions of either the characters or the natural scenery readers can always feel the writer’s strong patriotic mood.” (Ibid.) The novel gained its popularity among Chinese readers mostly due to the fact it met the socialist expectation of proletarian narrative, which can be traced without difficulty: “This time the protagonists are not the upper class, of whom Jókai already gave extensive descriptions in earlier works, but the residents on Hortobágy: pure and innocent countrymen, the horse-herds and the cow-herds.” (Ibid.) From this, one can see that compared to the narrative about Hungarian upper class, more interest was attached to the focus on the life of the Hungarian masses in the Chinese context. As a matter of fact, the dominant discourse of socialist literature in the Chinese context had cultivated a literary taste that always regarded writing on the proletarian class as orthodox, and the popularity of The Yellow Rose could be a result of this type of literary taste.

Departing from Hegedüs’s article which introduced and commented on selected works of Jókai, epitomizing Jókai’s domestic canonization, China initiated a consistent investment in Jókai’s translation, thus promoting his canonization in the Chinese context. Hegedüs must have be considerably influenced by Ferenc Zsigmond, who in a highly influential Hungarian monograph published in 1924 presented the view that Jókai’s writing flourished the most in the period between 1855 and 1875, and twelve of the novels written that time created “the grand cycle,” which should be regarded as the best part of the writer’s literary production (Zsigmond, 1924, pp. 172–222). This domestic canonization of Jókai, an authoritative one, had an impact on the Chinese reception through Hegedüs. China began with the process of selection in the 1950–60s. Taking Jókai’s participation in the 1848 Revolution as the starting point, the Chinese mapped him through his representation of Hungarian history of the 19th century, just like Hegedüs did. Regarding feudal society and its reform in the early 19th century, An Hungarian Nabob was mentioned; about the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Hungarian Sketches in Peace and War (1850), Egy bujdosó naplója [Diary of an Outlaw] (1851) and The Baron’s Sons; about the capitalist society and the bourgeoisie, Az arany emberFootnote 34 and Black Diamonds. These four novels, i.e., An Hungarian Nabob, The Baron’s Sons, Az arany ember and Black Diamonds were highlighted as Jókai’s best by the Chinese selection, which were all translated in the 1980s and became available for Chinese readers. Three of them, together with Debts of Honor and The Poor PlutocratsFootnote 35 (translated separately in 1985 and 1998), fall accurately into Ferenc Zsigmond’s “the grand cycle.” As for The Yellow Rose and An Hungarian Nabob, they were also canonized domestically considering either their popularity among Hungarian readers or their importance to the presentation of the nineteenth-century Hungarian history. All these imply that Jókai’s canonization in China was by no means a result of the market, but a production of cultural exchange guided by political motive, during which uncensored translation and circulation based on artistic needs would not be very feasible.

Having stagnated in the 1970s, Jókai came back into the lives of Chinese readers in the 1980s due to the re-opening of China. Generally speaking, his reception during this period was still overwhelmingly rooted in socialist ideology, largely following and inheriting the prototype formed in the 1950–60s. Before the 1980s, a rather solid literary discourse surrounding Jókai had been established, firmly rooted in the social and cultural soil of socialist China; its fundamental, if not prominent, impact would be proved by Jókai’s reception in the 1980s. An interesting case which clearly presents this succession between the Jókai’s reception of the 1950–60s and that of the 1980s is An Hungarian Nabob, which was published in 1980 but with a preface written in 1956, as noted in the page (Mei in Jókai, 1980, p. V). One may suspect that the novel was actually translated as early as in the 1950s, which implies that the translator must started his project much earlier than we see.

During the 1980s, Jókai’s critical realism—an idea of Hegedüs again—had been reiterated by Chinese readers when discussing his work. Critical realism was an important term in socialist literary discourse, which in China was mostly associated with the Soviet writer Maxim Gorky (1868–1936).Footnote 36 This discourse regarded the major nineteenth-century European realist writers like Dickens, Stendhal, Balzac and Tolstoy as the “prodigal sons of the bourgeoisie” who described “the utter senselessness of social life and of existence in general” (Gorky, 1978, pp. 337-338). Critical realists were said to have outgrown their environment and to treat it critically by always exposing its negative sides, carrying a pessimistic consciousness of the individual’s social defenselessness and alienation (Ibid.). Simply speaking, critical realists were said to have described the dark reality of capitalist society. By adding “critical” as a prefix to make a distinction from realism in general, socialist critics developed their own literary theory;Footnote 37 realism was therefore imprinted with socialist insights. Shuwen Gao’s retrospection captures the essence of critical realism and its epidemic in China since the 1950s:

Critical realism did not originate in China, and there is no such term in the works of Marx and Engels. In fact, it is a theory derived from the political needs and the intention of one-sided negation in the Stalin era through the Soviet writers’ conference, which stipulated that writers and artists uniformly abide by the creative method of socialist realism. ... Critical realism was introduced into China together with socialist realism and has been regarded as a classic since the 1950s, [...] which was due to the far left line of “taking class struggle as the key link” occupying the dominant position in the political field of our country at that time, and it indeed played the role of theoretical tool with its “left” content (1989, p. 9, p. 65).

It shows that under the socialist construction, critical realism was regarded as representing the most progressive, revolutionary and rebellious literary trend in the 19th century. Hegedüs’s comment on Jókai as a critical realist was quoted repeatedly by the Chinese side, directly or indirectly,Footnote 38 to the extent that it became a kind of official rhetoric on Jókai in China. What lies at the core of Hegedüs’s view is this passage:

The word “romanticism” is not enough to explain the fundamental thought in his novel. The methods he used to distinguish the basic contradiction in society or compare the progressive with the retrogressive are those of critical realism.Footnote 39 He embraces progress and humanism, [...] advocates science against superstition, and believes in the infinity of the human race (Hegedüs, 1954a, 1954b, p. 104).

Hegedüs did not so much mean to separate Jókai from romanticism, as to add the dimension of critical realism to the writer in whom he observed his link to reality:

This type of romanticism is not for escaping from reality, but to push the internal possibility of reality to its limits in order to transform the reality; it has a realistic tendency and presents realistic principles. Jókai’s oeuvre is the representation of romantic description and realistic inclination, which helps his writing of reality reach a rich and high artistic level (pp. 92–93).

His idea of Jókai as a critical realist was largely absorbed by the Chinese, but in the Chinese context its implication was extended to also include the writer’s criticism on feudalism. As a representative piece of writing about Hungarian feudal society in the early 19th century, An Hungarian Nabob was received as “a famous piece of critical realism in Jókai’s early career” (Mei in Jókai, 1980, p. III). Two aspects of its social criticism were observed. Firstly, “he uses the story of a typical landlord to boldly reveal the extravagant life of feudal aristocracy and satirize their ridiculousness and stupidity” (p. IV). Much importance was attached to the last scene of the novel where John Kárpáthy makes a confession—“a self-criticism of his aristocratic life” (Ibid.): “But what is happiness? Money? possessions? power? No, none of these. I possessed them all, and yet I was not happy” (Jókai, 1980, p. 282). Secondly, “he catches every opportunity to mock ruthlessly the bourgeoisie” (Mei in Jókai, 1980, p. IV). Here “the bourgeoisie” largely refers to the French banker in the novel, from whom the writer’s exposure to “capitalist philistinism” (ibid.) could be seen. The fact that Jókai did not write directly about peasant life under feudal rule was regarded as regrettable; however, an overall positive attitude towards the writer’s criticism of the society was still shown, especially when he wrote “Say not that I paint monsters, it is life that I describe” (Jókai, 1980, p. 166) when describing the complicity between Abellino and Mrs. Meyer in depraving Fanny, an innocent girl.

Debts of Honor also describes early nineteenth-century Hungary, but with more focus on the conflicts between the progressive bourgeoisie, represented, for example, by Lorand, and the conservative aristocracy, such as Gyáli. Lorand and Gyáli used to be friends in college. While the former is actively involved in the Hungarian reform, the latter persecuted him by dastardly means such as betrayal, deception and false accusations. The belief was formed in the Chinese context that “Jókai regarded it as his duty to praise the former type and criticize the latter” (Tang in Jókai, 1985, p. 7) because of the notice of the writer’s self-confession: “I witnessed many tragedies and peculiar phenomena in real life, which were later proved to have featured our nation. [...] In public life I saw enough evilness and ugliness, which I never stop denouncing” Footnote 40 (Jókai in Tang, 1985, p. 7). It is evident through the two examples that the Chinese’s perception of Jókai’s critical realism was rather vague, deviating from the theory’s supposedly exclusive criticism of capitalist reality. One should suspect that this vagueness was a consequence of the untenable theoretical foundation of critical realism. On the one hand, the Chinese might have wrongly recognized the writer’s criticism of feudal society as that of capitalism, and regarded it as part of critical realism. On the other, they sometimes confused critical realism with realism in general, which again disclosed the ambiguity of the theory. For instance, such a statement of Jókai’s realism follows the introduction of the writer as a critical realist:

Jokai himself was profoundly convinced that real life and his imagination were in full agreement, and he never understood why the critics, in his novels, failed to perceive the effects of realism on which he himself always relied. His wonder at this criticism was all the greater as he also regarded his method of writing as truly realistic (Mei in Jókai, 1980, p. III).

This comment was borrowed from another Hungarian critic, Sándor Hevesi (1873–1939), usually known as Dr. Alexander in the English-speaking world, who in his article emphasized the writer’s faithfulness to the real Hungarian life: “it is rooted in the very soul of the writer as the true expression of his reaction to facts and surroundings” (Hevesi, 1929, p. 363). In his view, realism is a method of writing barely confined to the dedication to certain facts and realities. The inconsistent understanding of critical realism in the Chinese context did not hinder the recognition of the two novels as a canonical presentation of the Hungarian life under feudalism.

The translation of The Baron’s Sons displayed a Hungary-Soviet Union-China mode of cultural exchange between socialist countries, which placed emphasis on revealing Jókai’s idealism. Translated from the 1959 Russian version,Footnote 41 the Chinese edition reiterated the Soviet interpretation of the novel and its writer, as can be seen from the fact that rather than offering another introduction, it contained the translation of the original Russian preface to the book, thus implying a strong affinity with the latter.Footnote 42 Due to this superposed socialist reading, the novel was defined as “a real paean to Hungarian National Liberation of 1848-1849” (BaiFootnote 43 in Jókai, 1983, p. 760). but not without the presence of idealism. On one hand, Jókai’s descriptions of revolutionary scenes and heroes were highlighted, with the assertion that “he wrote them with the most authentic historical materials and the greatest enthusiasm” (p. 756). For instance, what appeared impressive was said to be “his powerful writing of the heroic journey of the Hussars returning to the revolutionary motherland from Austria” (p. 757), which was “a real tribute to the heroic fight of the Hungarian warriors, showing an endless stream of collective struggle for the freedom and happiness of the motherland in front of the readers” (pp. 756–757). On the other hand, much controversy was aroused by the observation of idealism in the presentation of the revolution. In the first place, idealism was captured in Jókai’s opinion about the method of revolution: “When he wrote this novel, his heart was full of utopian fantasy: he wanted to use ‘national unity’—an improved rather than armed way—to idealize the revolution, thus making up for the pity of defeat” (p. 756).

Jenő Baradlay’s letter before his execution was seen as a typical expression of this opinion. The mentioned letter must refer to the one Jenő dedicated to his mother, in which he writes: “When I was small and you used to fall out with each other, I was often the means of effecting a reconciliation. Now once more that shall be my mission” (Jókai, 1983, pp. 688–689). Here Jenő mentions the tension between his parents and his mediating role, but the Chinese must read from it a strong implication of the antagonistic relation between the national progressives and the international conservative feudalist forces and the writer’s endorsement of reconciliation as the success of the revolution. Secondly, his idealism was observed in his presentation of the revolutionary camp:

Unfortunately, Jókai in this novel did not reflect the ruthless fight between the radicals and the moderates within the Hungarian revolutionary camp. However, the role of this fight in the fate of the national liberation war at that time was no less crucial than the intervention of the armed coalition of the Austrian Empire and the Russian Czar governmentFootnote 44 (Bai in Jókai, 1983, p. 757).

The Chinese interpretation above shows the writer’s disregard of the divergence as a problem and a symptom of idealist representation of the revolutionary camp. The Chinese criticism of idealism came from the summary of Jókai’s political life: he was weak in personality, indecisive in faith, and cautious as a liberal (Bai in Jókai, 1983, pp. 752-760). From the influence of far left socialist ideology followed a preference for such writers as Petőfi, a revolutionary democrat and a radical “writing hymns loved by all ordinary people” (758), while his friend, Jókai, gave the impression of a revolutionary idealist due to his moderate stance and later his active participation in the politics of the Dual Monarchy. Hegedüs’s comment should be put here as a summary of the Chinese attitude towards this writer: “Maybe sometimes he wavered in politics, or there were some contradictions, but he was always loyal to the memory of 1848” (1954, p. 99).

Some of Jókai’s other works were also read in a similar way in the Chinese context. On one hand, the Chinese acknowledged his positive and stirring presentations of the nineteenth-century history of Hungary—the age of bourgeois revolution and reform; on the other hand, they boldly criticized much on his political and therefore artistic deficiency, i.e. idealistic parochialism, presented in his work. Black Diamonds and Az arany ember are good examples to show this Marxist dialectical way of literary reading, which the Chinese often put together for discussion and comparison. The following comment well summarizes their perception of the two novels: “In these works, he promoted the utopian thought of national capitalism and tried to solve the basic contradictions of capitalism through ‘unity and mutual assistance’” (Bai in Jókai, 1983, pp. 755–756). Black Diamonds mainly describes the development of national industry— the coal industry—and the national industrialists’ struggle against a scam designed by aristocrats, clergymen and foreign capital. The novel was said to have faithfully presented Hungary’s political, social and economic situation in the early 1860s when the country had undergone external oppression and internal feudalism at the same time, and to some extent to reflect Hungary’s social contradictions and Hungarian people’s feelings and ideals as well as the historical process during that period (Tang in Jókai, 1980, pp. 474–475). However, the controversy aroused by the protagonist, Iván Berend, led to the conclusion of Jókai’s idealistic parochialism in the Chinese context. Iván is a near-perfect image of an industrialist under Jókai’s romantic writing, whose legendary identities include being a lieutenant of the hussars during the 1848 Revolution, a natural scientist, and most importantly, the owner of the Bondavára mine. Since Iván was perceived as a figure full of class prejudice in the Chinese context, Jókai’s perfection of characterization was only proven to be an idealistic portrayal of the bourgeoisie. From the Chinese perspective it was “out of his bourgeois prejudice on the proletarian class” (p. 473) that Iván says not only that “members of secret societies, socialists, and atheists [...] as soon as they get among our men they begin disseminating their vicious doctrines” (Jókai 1980, pp. 46–47), but also that “The poor are hungry and beg for bread, and when they have eaten they forget from whom they received nourishment. [...A]ll the burden of the present and the future seems to fall upon the less numerous and more exhausted class” (p. 336). The other aspect which was believed to have disclosed Jókai’s native idealism was Iván’s announcement that he would always share the profits with his workers equally: “the profits of this mine, so long as I lived, shall be divided between myself and my workmen” (p. 289). As the translator argued from Chinese perspective, “the bourgeoisie, even in the historical period when it undertook the task of revolution and progress, was still in essence the exploiting class. How could it be possible that they caused no harm to others?” (Tang in Jókai, 1980, p. 473). It is clear that a Marxist class consciousness was inserted into the interpretation of the novel, which can be verified from the frequent references to Marx in the Chinese introduction to the novel. In the context of this socialist discourse, Jókai’s dreams of a paternalistic and more humane capitalism appeared as “the writer’s kind wish, which is actually an unrealistic fantasy.” (Ibid.)

Az arany ember was appreciated for “its presentation of the unavoidable contradiction accompanying the rapid development of capitalism in Hungary of the 19th century” (Li in Jókai, 1981, p. 7), but more attention was paid to its presentation of idealism on envisioning the future. It was firstly regarded as a departure from and therefore contrast to Black Diamonds:

Timar also belongs to the type of national capitalists like Iván. However, he lacks Iván’s ambition to fight for national industrialization, but appears as a frustrated image experiencing severe inner conflict. Black Diamonds praises the development of Hungarian national capitalism, while Az arany ember focuses on the contradictions in the development of capitalism and the evil of money (p. 8).

In other words, a disillusionment with capitalism or even an anti-capitalist inclination was read as the main idea of the novel. The evilness of capitalist society was found to have shaped almost every character: Timar’s inner struggle between the two worlds, Theodor and Athalie’s wickedness and self-destruction, a group of money-worshipping people such as Fabula, Sophie, Brazovics and Sandorovics (pp. 9–11). And the confrontation between Teresa, the mother self-exiled to a hidden island, and Sandorovics, the representative of oppressive legislation, was perceived as presenting the novelist’s anti-capitalist thoughts (p. 11). Nevertheless, though seeing its difference from Black Diamonds, a similar idealism was still traced in it:

Both Az arany ember and Black Diamonds reflect Jókai’s idea that the ideals of the bourgeoisie about creative labor, free marriage, social unity and justice cannot be realized in his era, but in the future. Black Diamonds and The Novel of the Next CenturyFootnote 45 imagine an utopian socialist society based on Robert Owen’s experimental socialistic community while Az arany ember inherits Rousseau’s vision of utopia in which a small population live an equal, primitive, simple and bartering life by following the “social contract” (p. 8).

Here the Chinese reviewer was insightful enough to observe two different modes of utopia which did become one of the main themes of Jókai’s works in the 1870s. However, what he saw from it must be no more than a bourgeois whim, as he continued: “The author’s disillusionment with capitalism was only temporary when he wrote this piece, because following its publication he still penned some bourgeois characters who played positive roles in political life.” (Ibid.) That is to say, according to the Chinese interpretation, the writer never really lost faith in capitalist society and bourgeois politics. If an idealism on the class issues was read from Black Diamonds, from Az arany ember an idealism on the social system was noticed, for both of which no empathy was shown in the socialist context, which after all was far from the future imagined by Jókai.

The nineteenth-century Hungary Jókai depicted was a historical period when the rising bourgeoisie challenged the feudal system of the Habsburg Dynasty by demanding national independence, democracy, reform and progress. Within the context of socialist discourse, Jókai was regarded as a bourgeois writer and his work as the representations of the capitalist society of nineteenth-century Hungary. On one hand, Chinese readers affirmed Jókai’s writing of the oppressive history of Hungary in the 19th century, e.g., his exposure of the life of Hungary’s ruling class constituted by conservative aristocracy and churches, his passionate description of Hungary’s revolution and liberation, and his presentation of the national industry and culture in Hungary. On the other hand, they not only constantly warned themselves against Jókai’s bourgeois prejudice and parochialism but also thought of him as a tragic Rousseau/Owen-style utopian and idealist.

An exception to this is the translation of The Poor Plutocrats in 1998, in which one can see less influence of the political discourse of socialism for the first time. With less didactic rhetoric inherited from the 1950s, there are even reflections on Chinese or worldly reality inspired by Jókai’s novel. From the writer’s presentation of the mysterious story of a baron-bandit or bandit-baron, a real picture of the world was discerned in the Chinese context:

The plots are strange, the story seems ridiculous, and the actions of the characters are beyond the imagination of ordinary people. But thinking about it carefully you will realize that such people and things are not only for the nineteenth-century Hungary but fill every corner of the world from ancient times to modern era. In political arena, there are quite a few examples, ranging from ancient emperors and officials to modern politicians, who wear a mask of hypocrisy because they always carry a duality with them—decent in front of the public, but corrupted behind the scene. Counterfeits in market and plagiarism in academia are all under the cover of economic development and cultural prosperity. The novel uses a series of dramatic plots to push a real scenario of human world, which is often hidden—rich is bandit and bandit is rich—into the limelight; surprise and thrill are the effects (Tang in Jókai, 1998, pp. 5–6).

In this passage, Jókai was for the first time put beyond the political discourse in the Chinese context, restoring him to artistic significance. His romantic arrangements of plots and characters were recognized as artistic typification of, and therefore reflection on, real life. Compared to previous translations in which he had been always read through the lens of critical realism to interrogate his dealing with the Hungarian reality, this translation shows the possibility of capturing a broader sense of reality through his romantic writing. And I expect more of this type of Jókai.

The Chinese translation of Jókai’s work in the 20th century was almost always dominated by political discourse: “the literature of marginalized nationalities” in the early 20th century and “the literature of socialist countries” in the second half of the century. While the readers in the earlier period inserted modern China’s national consciousness into their interpretation of the writer, who therefore appeared strangely familiar to them, the readers in the later time were under the impact of socialist ideology, thus distinguishing themselves from the writer, who was regarded as a bourgeois novelist. For the latter, they not only constantly warned themselves of his idealist parochialism but also thought of him as a tragic Rousseau-style utopian. In the 21th century, when translation has almost come to a halt, The Yellow Rose was once again translated in 2018. This time, the novel is put in one volume together with such canonical works as The Great Gatsby and The Lovely Lady, which are selected as the masterpieces presenting the theme of “the shadow of love” (Jókai et al., 2018). By doing so, the Chinese edition has endowed Jókai with such world literature significance as that of F. Scott Fitzgerald and D. H. Lawrence. It may be a signal that the writer has started a new journey in China.

Notes

For a review of the formation of this term within Chinese context, see (Song, 2017, pp. 5–6).

For a review of the permeation of nationalist thinking into the cultural and literary field, see (Song, 2017, pp. 9–10).

It was the most influential cultural and literary movement in the first half of the 20th century, which advocated a new Chinese culture/literature based on Western ideas and values so as to distance from classical Chinese culture/literature based on the traditional Confucian system, with the writers of New Youth magazine as the pioneers.

It was the politicized consequence of New Culture/Literature Movement, when nation-wide protests occurred and spurred an upsurge in Chinese nationalism.

It is my translation of the original Chinese texts. All the translations of Chinese sources in this paper are mine.

The outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 was the turning point for the translation of foreign literature in China, when most of literary translation came to a halt.

This piece of incorrect information has long caused misunderstanding in Chinese academia, which can still be witnessed in some scholarly articles, e.g. (Qiu & Fu, 2019). They invariably assume that the book was translated from Bain's Midst the Wild Carpathians without knowing that the latter is a completely different story, while its real English counterpart, Manasseh, is unknown to them.

One can speculate that it had something to do with “Transylvania.” In There Is Only One God, the story is mostly set in Transylvania, and so is in Midst the Wild Carpathians. However, due to the usual association of the region with vampires in the English-speaking world chiefly because of the influence of Bram Stoker's famous novel Dracula as well as the many later film adaptations, it has been often replaced by “the Carpathians,” the mountains surrounding it. It is possible to happen that Chinese related a story about Transylvania, There Is Only One God in this case, to a title carrying “the Carpathians” in it.

This piece by Zhou Zuoren was never published or put by Zhou into any of his collections when he was alive.

The Chinese titles are followed by their Esperanto titles in the book, as shown on the cover. The Hungarian originals are “Egy lengyel történet” (1863), “Az elesett neje” (1850), “Melyiket a kilenc közül” (1856).

Though born and educated in Hungary, Reich spent his later life in the Anglophone world, especially Britain, and published works in English.

A Hungarian essayist, critic and literary historian who wrote a history of Hungarian literature in English.

The biggest difference between the writer’s English and Chinese reception is their attitude towards his national agenda. Many of Jókai’s works were severely abridged for English edition in an effort to make them appeal to English market, on which Kádár gave insights: “The translators did not agree to Jókai’s anti-capitalistic and nationalistic views and therefore they either simply left out these elements from their translations of the novels or they adjusted the texts to the taste of the British and American public. [...] In spite of these omissions only those of his works became popular [...] whose literary form had been familiar to the readers: gothic novels and historical romances. Because of a general unfamiliarity with Hungarian history, Jókai’s historical novels could only be read as novels of adventure. His few Tendenzromane that were translated into English never attained a second edition” (Kádár, 1991, p. 542). This passage captures the part characteristic of Jókai’s reception in English context: the maximization of his tale-telling ingenuity and the minimization of the nationalistic agenda. Though the Chinese inherited the interpretation of Jókai as a romancer from English context, they did not reject the nationalistic aspects as the English public did; instead, they found a way to build the link between the writer and the nation. If pure romance was made to appeal to English taste, a nationalistic dimension had been added to it to make it appeal to Chinese taste.

For a review on the views of ethnic relations between Hungary and China in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries cf. (Chang, 2012).

Zhou mentioned once that Yong Sun (1902–1983), a writer and translator of Hungarian literature, made a translation from Esperanto, which he did not read but surmised to be an unabridged edition (Zhou, 1982, p. 227).

Zhou was one of the representatives. As a scholar of classical Western literature, he introduced pastoral in different occasions. See (Zhou, 2009, pp. 210–212, pp. 216–217).

Since Qichao Liang’s advocacy of the Novel Revolution in 1902, the novels that talked about national and social issues were welcomed, with its peak in the New Culture (Literature) Movement (1915–1923), while those with the theme of love and marriage were regarded as the old and outdated pattern developed from classical Chinese novel, though the latter remained the mainstream of prose for certain time in the early 20th century. Cf. (Lin 1997). This categorization was also applied to the translated works by such writer-translators as Zhou.

The other pioneers were Lu Xun, Mao Dun and Congwen Shen. For a review on local literature and its theories in the twentieth-century China, cf. (Li 2019).

For a thorough study of Zhou’s local literature theory, cf. (Yu 2008).

The Hortobágy is a region inside the Great Hungarian Plain.

Long prose, especially novels, were partly criticized as the old pattern of literature since the classical Chinese novels often contained many chapters.

This article might be an adaptation of Hegedüs’s Hungarian paper entitled “Jókai” since they are quite similar to each other. In its Hungarian version, Hegedüs also introduced Jókai from four aspects, namely, a patriot, an optimist, a humanist, and an enthusiast about natural sciences (1954, p. 3).

The period of 1966–1976 is not considered here due to its social and cultural stagnation caused by the Cultural Revolution.

The title is shown in both Chinese and English.

In the afterword of Yiwen, the editor wrongly mentioned that Jókai wrote a book called For Liberty, which must refer to this one.

This series collected several books from Hungary and the Soviet Union and published them during the period of 1951–1953, which exclusively present the topic of national revolution and liberation.

Two among them, “Comorn” and “The Szekely Mother,” were extracted from Hungarian Sketches in Peace and War, Jókai’s short story collection in 1850. The Egy Nemzeti Hadsereg” [A national army], “Szolnok” (newspaper article March 12, 1849), “A kis szürke ember” [Little grey man], and “Peisi Laixin” [A letter from Pest], which must be written during and right after the 1848 Revolution. “Egy Nemzeti Hadsereg” is identical with Chapter 19 in The Baron’s Sons. (This chapter was abridged in the English translation.) Therefore, the book is not a short story collection but a cluster of stories, journalism, and excerpts from novels.

The author of the preface is unknown; the translator of each short story in the collection is noted.

Departing from The Yellow Rose, Tang translated many of Jókai’s works in the 1980s, which made him the most important translator of Jókai in the second half the century.

For Zhou Zuoren’s life cf. (Zhou 1982).

This passage was mentioned again by Tang in the preface of a story collection of Jókai (including “The Yellow Rose”) called Yizhuo Shisanren [Thirteen People around the Table] (the Chinese translation of “The Bardy Family,” a short story in Hungarian Sketches in Peace and War) in 1982.

It had two English translations: Timar’s Two Worlds and Modern Midas. The Chinese translation was made from a German translation, which was a rather faithful representation of the ST title, approximately meaning The Golden Man.

The Chinese translation bore the title The Black Mask, very different from either the ST title Szegény gazdagok [Poor Rich] or the English title The Poor Plutocrats.

While Hegedüs is known to have learned the term from Lukács, Chinese literati and critics generated a understanding of the term by mainly learning from Gorky. Though with this difference, Hegedüs’s utterance of Jókai’s critical realism still aroused much attention among the Chinese.

They did the same to romanticism, hence active romanticism. As Gorky explained: “Active Romanticism strives to intensify man’s will to life, and rouse him to rebellion against reality and whatever oppresses it” (Gorky in Kaun, 1939, p. 439).

Hegedüs’s words can be seen in different variations in many prefaces to Jókai’s Chinese translations of either the 1950s or the 1980s.

Some critics believe that the core of Gorky’s critical realism is a combination of a kind of “active” or “progressive” romanticism and realism; see (Kaun, 1939).

This quotation must be taken from Hegedüs who mentioned it in his article.

The year here implies again the succession of Jókai’s translation between the 1950s and the 1980s.

The period of the 1960–80s witnessed the Sino-Soviet split, when there was a divergence on the mode of socialist development between them. But they still regarded each other as belonging to the same camp of anti-capitalist countries.

I put the Chinese translator’s name here because the Russian translator, the original author of the preface, is nowhere to be traced.

As a matter of fact, the Russian introduction/its Chinese translation seems to downplay the fact that it was the Russian army which defeated the revolution, attributing the failure mostly to the divergence within the national progressives.

Jókai’s utopia novel in 1872–74, which predicts a revolution in Russia and the establishment of a totalitarian state there, and the arrival of aviation. It was banned in Hungary in the decades of the Stalinist Era due to its allegorical satire on totalitarianism.

References

The Chinese translations of Jókai’s work

Jókai, M. (1927). Huang Qiangwei [The Yellow Rose] (Trans., Zhou, Z.). Commercial Press.

Jókai, M. (1933). Xiongnu qishilu [Manasseh] (Trans., Zhou, Z.). Commercial Press.

Jókai, M. (1934). Bolan de gushi [A Polish tale] (Trans., Zhong, X.). Zhong, X. (Ed.), Bolan de gushi [A Polish tale] (pp. 1-64). Zhengzhong Press.

Jókai, M. (1956). Weile ziyou [For liberty] (Trans. Zhuang, S. et al.). People Publishing House.

Jókai, M. (1960). Huang Qiangwei [The Yellow Rose] (Trans., Tang, Z.). People Literature Press.

Jókai, M. (1980). Hei zuanshi [Black diamonds] (Trans., Tang, Z.). People Literature Press.

Jókai, M. (1980). Yige Xiongyali fuhao [An Hungarian nabob] (Trans., Mei, S.) Shanghai Translation Press.

Jókai, M. (1981). Jin ren [The golden man/Az arany ember] (Trans., Li, X). People Literature Press.

Jókai, M. (1983). Tieshi xinchangren de ernv [The baron’s sons] (Trans., Bai, B.). People Literature Press.

Jókai, M. (1985). Xinyu zhi zhai [Debts of honor] (Trans. Tang, Z., & Ding, J.). Shanghai Translation Press.