Abstract

This study shows that the Turkish expression hani exhibits interesting properties for the study of the semantics and pragmatics interface, because, on the one hand, its function is merely pragmatic, but on the other hand, it is subject to the truth-conditional effect of other constituents at LF. This notwithstanding, studies on this expression are remarkably scarce. The only attempts to describe its properties are Erguvanlı-Taylan (Studies on Turkish and Turkic languages; proceedings of the ninth international conference on Turkish linguistics, 133–143, 2000), Akar et al. (Discourse meaning, 57–78, 2020), and Akar and Öztürk (Information-structural perspectives on discourse particles, 251–276, 2020). In the present study, we introduce the first formal semantic and pragmatic treatment of clauses containing hani. Unlike previous accounts, we claim that hani can have one of the following two major pragmatic functions: making salient a proposition in the Common Ground or challenging one in a past Common Ground, therefore requiring a Common Ground revision. Despite its variety of occurrences, we argue that hani has a uniform interpretation and provide a compositional analysis of the different construals that it is associated with. Furthermore, we show that a formally explicit and accurate characterization of hani clauses requires operating on indexical parameters, in particular the context time. Therefore, if our proposal is on the right track, hani clauses may provide indirect empirical evidence in favour of the existence of “monstrous” phenomena, adding to the accumulating cross-linguistic evidence in this domain (see Schlenker in Linguistics and Philosophy 26(1):29–120, 2003 and much work since then). The definition of monsters is intended as in Kaplan (Themes from Kaplan, 481–563, 1989).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Preliminary remarks

The Turkish expression hani shows similarities with the German discourse particles ja and doch (Kratzer 1999, 2004, Coniglio 2007, Egg and Zimmermann 2012, Zimmermann 2012, Rojas-Esponda 2014, Döring et al. 2019, among others). Indeed, both German ja and doch on the one hand and hani in several of its occurences on the other hand seem to generate the effect of reminding the addressee that their prejacent is true.Footnote 1 This effect is illustrated in (1).

However, in this paper, we observe some important features that distinguish hani from the above mentioned German discourse particles. First, (1a) is restricted to contexts where the prejacent of hani is part of the Common Ground with no exceptions (see Sect. 2). This is not so for ja, as reported in Kratzer (1999, 2004) (see Kratzer 2004, pp. 126-127 for a detailed description). The same point was brought to our attention about doch by an anonymous reviewer, who offered (2) as an example.

Secondly and more importantly, Turkish hani has a second primary use in which it carries intonational prominence and, rather than functioning as a reminder, it challenges the truth of the prejacent.Footnote 2 Note, by the way, that in these cases, the past tense marker is obligatory, and this is crucial for the possibility of challenging effects as discussed in Sect. 4 (see (3)).

The challenging nuance that we observe in (3) resembles closely the effect of English negative polar questions like (4), as the translation in (3) indicates.

Similarities of this type are what led Akar et al. (2020) and Akar and Öztürk (2020) to the conclusion that hani sentences, such as (1a) and (3), are equivalent to negative polar questions with outer and inner negations, respectively. However, in Sect. 5, we show that the resemblance is only superficial in that hani clauses display stricter felicity conditions.

The main contribution of this paper is a unified analysis of hani in the two very distinct uses mentioned above. In particular, we suggest that hani in both uses carries the same expressive presupposition. Our analysis is compatible with the view according to which discourse particles introduce felicity conditions on the utterance of the sentence and do not directly contribute to its truth conditions (see Kratzer 2004; Gutzmann 2009; Egg and Zimmermann 2012, among others). However, we depart from some of these approaches in claiming that this condition is encoded in the lexical entry of hani in the form of an expressive presupposition in the sense of Schlenker (2007) and Sauerland (2007). Our hani carries a definedness condition which makes reference to contextual parameters (i.e., speaker, addressee, world or time of the utterance context). In this sense, its presupposition is “indexical and sometimes shiftable” (see Schlenker 2007).

The reference to indexical parameters in the presupposition of hani and the role of the past tense are important ingredients of our explanation for the different felicity conditions of (1a) and (3) that we illustrate in Sect. 2. Specifically, we show that the past tense in (3) manipulates the time at which the condition needs to hold. This, we claim, is an effect of “indexical shift”, a phenomenon that has received much attention in recent literature (see Schlenker 2003 and much work since then). A comprehensive study of indexical shifts, including temporal shift (“Temp Shift”), is Deal (2020).

Although shifting of contextual parameters has been documented in other domains of grammar, the fact that it can be employed in the semantics of discourse markers is a novel observation of this paper. Noticeably, this distinguishes the patterns of hani from better known facts concerning German discourse particles and negative polar questions and calls for a distinct analysis.

The expressive presupposition and the temporal shift that we propose for hani below lay the formal grounds for an understanding of the different discourse functions of clauses with hani. Those grounds, we argue, are to be found in the syntax-semantics interface. This is the component of the two uses of hani that we investigate here. Instead, our illustration of the different discourse pragmatic effects of these two uses remains at a more descriptive and intuitive level.

Whereas this paper contains no formal proposal regarding conversational exchanges and discourse, we do, however, adopt the following notions described in the literature on discourse analysis, dynamic semantics and Speech Act Theory. In the paper, we employ Stalnaker’s notion of the Common Ground (CG) intended as the set of propositions that are commonly and mutually believed by the participants of the conversation (see Stalnaker 1977, 1978, 1999, 2002). However, we make the two following additional assumptions regarding the CG. First, we follow Karagjosova’s (2004) proposal that the CG not only necessarily increases over the time of the conversation, but might also be reduced by the deletion of some propositions that become controversial. Sentences like (3) appear to trigger such CG revisions in light of novel evidence challenging one or more shared beliefs.

Secondly, we assume that not all propositions in the CG are equally salient/active at the time of the conversational exchange. In each conversation, a different subset of CG-propositions can be made salient, for example by asserting them, in a manner similar to how the mention of an individual by name makes that individual salient for further pronominal reference. We take the reminder function of hani illustrated in (1a) to trigger exactly this effect. Similar notions of saliency have been discussed in detail in Karagjosova (2004), Döring (2016), and Döring et al. (2019). Here we would like to point out that, unlike in some of these studies, what hani sentences make salient are propositions that are already in the CG and not just commitments (see Groenendijk and Stokhof 1984, Groenendijk 1999 for similar ideas on common ground structuring). See also Sect. 3 for further comments.

Another crucial issue regarding the reminder uses of hani needs to be clarified in advance. In these uses, the utterance conveys a proposition that is already in the CG and therefore is “uninformative”. However it has been convincingly argued in the literature that this type of redundancy does not lead to ungrammaticality (e.g., see Gajewski 2002a,b, Krifka 2017).What is interesting about Turkish is that this type of redundancy is tolerated only in the presence of hani.Footnote 3 This we take to be an effect of Heim’s (1991) principle of Maximize Presupposition!Footnote 4

Finally, one last issue concerning (1a) that we would like to address here is the role of ya. Whereas the presence of ya affects the intonation of these sentences (see Akar and Öztürk 2020, Akar et al. 2020), it does not affect their semantic and pragmatic contribution or their felicity conditions. Since this paper concerns the semantic and pragmatics of hani, it does not address the differences between sentences with and without ya (if there are any), but takes them to be phonological variants of the same construction.Footnote 5

Finally, a brief note on terminology is in order. Since our analysis takes examples like (1a) as declarative sentences and (3) as questions, we use the labels D(eclarative)-hani and Q(uestion)-hani to refer to these types of hani clauses in the remainder of the paper.

2 Differences between D-hani and Q-hani clauses

In this section, we show the three crucial respects in which D-hani and Q-hani clauses differ: they display distinct but related felicity conditions, they differ in the type of assertion they convey (a declarative and question, respectively), and there is a difference in the function of the past morpheme between them.

Given that we analyze Q-hani clauses as constructions different from negative polar questions in English, we henceforth use different translations for them. Upon the suggestion of one of the anonymous reviewers, we translate them as regular polar questions with an additional sentence ‘ ’ to indicate their presuppositions. Similarly, we mark the presuppositional content of D-hani clauses as ‘

’ to indicate their presuppositions. Similarly, we mark the presuppositional content of D-hani clauses as ‘ ’ in our translations of them. The different font is intended to indicate that these are not parts of the assertion, but are encoded as presuppositions. Nevertheless, these translations remain as approximations, and do not fully capture the semantic and pragmatic effects described in detail in the sequel.

’ in our translations of them. The different font is intended to indicate that these are not parts of the assertion, but are encoded as presuppositions. Nevertheless, these translations remain as approximations, and do not fully capture the semantic and pragmatic effects described in detail in the sequel.

2.1 Felicity conditions of hani clauses

In contexts where the speaker and addressee do not already believe the prejacent to be true, D-hani clauses are not felicitous, as shown in (5).

Hani in (5b) becomes perfectly fine, and obligatory, in a context like (6) below, where both participants of the conversation believe the prejacent to be true.

We take this data as an indication that D-hani clauses presuppose that the participants of the conversation believe the prejacent to be true.Footnote 6

When we turn to Q-hani clauses, crucially, we observe that Q-hani clauses are not acceptable when the truth of the prejacent is currently believed. This is shown in (7c). Unsurprisingly, the D-hani clause is acceptable, as shown in (7b).

The following two examples show that Q-hani clauses presuppose that the belief that the prejacent is true held in the past rather than at the present. (8a) is a context where this requirement is satisfied and the Q-hani clause is just fine, (9a) is one that does not, and Q-hani is unacceptable.

In the context in (9a), Zeynep never believed the prejacent to be true. Accordingly, the sentence in (9b) addressed to Zeynep is inappropriate while it would not be so if it were addressed to Mehmet.

Given this, we take the above facts as evidence that the difference in felicity conditions between the two types of clauses lies in the time at which the beliefs of the participants of the conversation must hold, as summarized below.

A second difference in felicity conditions between D-hani and Q-hani clauses is that D-hani clauses require a continuation, for which the content of the D-hani clause is relevant, instead Q-hani clauses can occur in isolation. This contrast is shown in (11).Footnote 7

2.2 Assertive components of hani clauses

In this section, we turn to the asserted component of hani clauses. According to our informants, D-hani clauses assert their prejacent. This makes D-hani clauses systematically “uninformative” (Stalnaker 1978, 1999, 2002). This is because these clauses also presuppose their prejacent. In this section, we argue that this unusual property of hani is precisely what triggers its reminding discourse effects. Intuitively, D-hani clauses are used as reminders and “stage openers” to legitimize an upcoming assertion as in the example (6), repeated in (12).

We suggest that the speaker intentionally fails to be “informative” in uttering the hani clause in (12b), and indicates this much via the presupposition of hani. Notice that the speaker violates Grice’s (1975) Maxim of Manner and Quantity ‘be brief’, as well as Stalnaker’s conversational principle that what is presupposed cannot be asserted (i.e., c + p ≠ c) with such an unorthodox move, which creates the inference that she has good reasons to do so.

What justifies these violations is the intention of the speaker to convey that an already existing shared belief is salient in that it is related and relevant to a more general point she is making (e.g., a suggestion or a piece of advice). In fact, this property of linguistic expressions has been investigated quite extensively in the literature on discourse particles/markers and in speech act theories. For example, Krifka (2017) explicitly states that Stalnaker’s conversational principle is not a strict requirement on discourse, but might follow from a Gricean maxim.

Typically, updates like c + A indicate that comc(A), the new commitments expressed by A, are not already present in c [...], otherwise there would be no point in performing A in the first place (the “first principle” in Stalnaker (1978)). However, we would not want to express this as a strict condition for updates, [...]; rather, it should follow from Gricean reasons, perhaps as a consequence of the Maxim of Manner, “Be brief!”. In fact, speakers repeat themselves, and often with good reasons, as they might assume that the commitments expressed by the speech act already be there, but still have to be stressed and made salient. (Krifka 2017, p. 366)

Indeed, building on Döring’s (2016) and Döring et al.’s (2019) claim regarding ja and doch, we suggest that one way to make a proposition salient is flagging the “uninformativity” of its utterance. In uttering a sentence that comes with the presupposition that essentially indicates that the information in the sentence is not new to the speaker and addressee, the speaker indicates to the addressee her awareness that she is violating a conversational principle. The intention of the speaker is for the addressee to suspend her potential reaction to the violation and to understand the purpose of it. In our cases, such purpose is to move the prejacent to the subset of salient propositions in the CG.

However, the question of why hani is obligatory in reminding uses still persists. In other words, why is it not enough to utter a CG proposition to create this pragmatic effect without hani, if indeed one can flout a conversational principle to make space for another discourse move? We believe that there are two reasons to opt for such a discourse marker/particle to create this effect. First, without hani, it may not be always obvious that the speaker is violating a conversational principle on purpose, rather than by accident. Second and more importantly, this pragmatic effect is mainly legitimized by Heim’s 1991 proposed principle of Maximize Presupposition!. Maximize Presupposition! requires that among two equally informative utterances in a given context C, one will opt for the one with the strongest satisfied presupposition. Given that the context in (13a) entails that speaker and addressee are aware of the existence of a vegan restaurant around the location of speech, the item that carries this presupposition must be preferred over the one that lacks it. Accordingly, the contrast between (13b) and (13c) below is due the principle of Maximize Presupposition!.

An important note is in order at this point. Given our claim that D-hani clauses assert what is already believed to be true, an anonymous reviewer indicates that we predict that they are L-trivial, in the sense of Gajewski (2002a), and therefore ungrammatical. However, we do not believe that we make such a prediction; here is why. According to Gajewski (2002a,b), a sentence is L-trivial if its L-skeleton is always true (or false); that is, if the sentence is true (or false) under any substantial “rewriting of it”, where substantial rewritings substitute every non permutation-invariant expression in its LF with variables. The lexical entry we propose for hani is not permutation-invariant, given that the truth of belief attributions depends on the world/time of evaluation, as well as the subject of the attribution. Hence, the LF skeletons of D-hani clauses are not predicted to result in a tautology. Less technically, according to our analysis, D-hani clauses are not predicted to be always true, as they can very well be undefined. In other words, just like many other cases of “uninformative” sentences Gajewski discusses in his work, D-hani clauses might flout the maxim of Quantity/Manner or violate Stalnaker’s conversational principle to generate certain pragmatic effects—e.g., making salient a CG proposition—but are not ungrammatical.

What justifies the redundancy of the assertion of D-hani clauses is its function of making the proposition in the CG salient since not all beliefs belonging to the CG are salient or active in a given discourse (see Karagjosova 2004). In more formal terms, one might devise a system where D-hani sentences move a CG proposition to a subset of the CG including only the salient and active ones.

Needless to say, there have been many other proposals introducing distinct structurings of the CG (see Krifka 2001, 2011, 2015, 2017, Farkas and Bruce 2009, Eckardt 2016). Others have argued that one must posit a distinct dimension to account for the pragmatic effects brought up by the use of discourse markers, such as expressive dimension (Gutzmann 2009, 2013). In this paper, we do not commit to any specific one of the above-mentioned views on saliency, and leave a refinement of this sort to further research.

In addition, Kratzer’s work on German discourse particles indicates that assertions of redundant propositions with those particles can be employed as “stage-openers” or grounds for an upcoming argument or comments (Kratzer 2004), which is also what we observed for D-hani clauses in the previous section.

Turning now to Q-hani clauses, they differ from D-hani ones in their assertive component. In the remainder of this section, we illustrate evidence supporting our proposal that Q-hani clauses denote questions, while D-hani clauses are declaratives. The first piece of evidence is the behaviour of hani clauses under quotational embedding.Footnote 8 As the baseline triple in (14) shows, a polar and a wh-question can complement the noun ‘question’ while a declarative clause cannot.

We use this as a test to diagnose the clause type associated with hani clauses. As the data in (15) show, Q-hani clauses are grammatical in the test configuration, whereas D-hani clauses are not. We take these data to suggest that Q-hani clauses denote questions, while D-hani clauses denote declaratives.Footnote 9

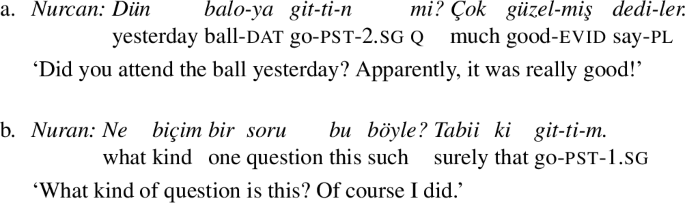

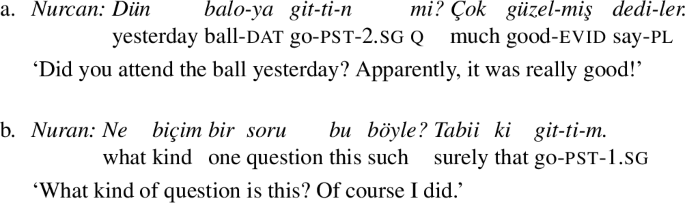

A second kind of diagnostics is what we call the “what kind of question is this?”-test. It is natural to react to the utterance of a question with the comment “What kind of question is this?”, whilst this reaction is not appropriate in the case of declarative sentences. This is illustrated in the baseline triple in (16), (17) and (18).

Q-hani clauses are compatible with “What kind of question is this?”, whereas D-hani clauses are not. This contrast is shown in (19) and (20).Footnote 10

Whereas the data above merely indicates a difference in the type of assertion between Q-hani and D-hani—interrogative and declarative, respectively—within the analysis below, we make the stronger assumption that Q-hani clauses are polar questions. Adding this assumption to the results from this section, we conclude the following:

What lends plausibility to the assumption that Q-hani clauses are questions of the yes/no variety is that it implies the minimum amount of covert material and the absence of just one item typically present in polar questions in Turkish, which is mI (see Aygen 2007, Özyıldız 2015, Kamali and Krifka 2020, and the references therein on the question particle in Turkish).Footnote 11

We conclude this section, discussing and rejecting the option that Q-hani clauses express why-did-you-tell-me-p? kind of interrogatives. Given its challenging function, one might wonder if the Q-hani clause in (22b) is semantically equivalent to why did you tell me that there is a vegan restaurant here.

Besides assuming that the LF of (22b) contains a large amount of unpronounced linguistic material, there is empirical evidence against this hypothesis. The data below are sufficient to refute this hypothesis.

Although a common response to a why-did you-tell-me-p question is an explanation (see (23b)), Q-hani clauses are incompatible with such replies, as illustrated in (24b).

The contrast shows that Q-hani clauses do not logically express a meaning equivalent to a why-did-you-tell-me-p? question, and is compatible with our assumption that they denote polar questions. The formal details of their composition are illustrated in Sect. 3.

We believe that our conclusions regarding the distinct assertive component of D-hani clauses and Q-hani clauses proposed in this section provide an account for the facts discussed at the end of the previous section; that is, the unacceptability of D-hani clauses in isolation versus the ability of Q-hani clauses to occur on their own. Indeed, given the redundant nature of D-hani clauses, they can have a pragmatic function only in the presence of a continuation, as discussed above. However, Q-hani clauses are not redundant, as their past presupposition is compatible with a genuine yes/no question regarding the truth of the prejacent at the time of the utterance.

2.3 Hani clauses and the past tense morpheme

As we previously stated, past tense morphology is obligatory in Q-hani clauses. However, we have not considered its contribution to the sentence thus far. This section presents evidence that the overt past tense in D-hani clauses affects the time of the prejacent as expected, while in Q-hani clauses it manipulates the time of the beliefs that are part of the presupposition by inducing an indexical shift. More concretely, we argue that the overt past tense makes a meaningful difference between (25a) and (25b), although they look stringwise identical, modulo intonation.

Let us first consider the case of D-hani clauses. In (25a), the past tense locates the eventuality at a past time, and therefore expresses that there was a vegan restaurant then. The following example confirms this much.

Since in (26a), Ali’s state of being in Istanbul extends to the speech time, and it has lasted three months at the moment of speech, the past tense morpheme in the prejacent of the D-hani clause is not acceptable. This is because the use of the past tense in the prejacent causes the D-hani clause in (26c) to express that Ali’s three-month stay extended to and ended at a past time, however, this would mean that even if Ali’s stay in Istanbul continues, it would exceed the three month period at the speech time, which contradicts the contextual information. Notice that this makes (26c) a presupposition failure, and not false, because as mentioned in Sect. 2.1, D-hani clauses presuppose their prejacent, and the prejacent of (26c) is false in (26a). The data therefore indicate that the past tense receives its ordinary scope and interpretation in D-hani clauses.

There is an apparent counterexample to this claim. Consider the example in (27). Although the predicate in (27b) carries a past tense morpheme, speaker and addressee appear to believe that there currently is a vegan restaurant at the location of speech.

Moreover, individual level predicates like the existential in (27b) are known to trigger an inference of non-existence of their argument when uttered out of context (Kratzer 1995). For example, in (28), Gregory is understood to be dead.

However, the counter-example is only apparent. As Musan (1997) rightly points out, the inference of non-existence (life-time effects, in her terminology) disappears once sentences like (28) are parts of larger linguistic contexts (see (29)).

In light of Musan’s (1997) discussion, the facts in (27) can be explained away. According to Musan (1997), contexts like (29) introduce a past encounter of the speaker with the person in question. Therefore, the past tense on the individual level predicate in the subsequent sentence seems to refer to that past experience. Informally speaking then, a sentence like (29b) conveys that there is a time t′ before the speech time t, and the speaker had a chance to have a closer look at Gregory at t’, and he had blue eyes at t′. Crucially, such a statement does not provide any information with respect to the current existence of the subject in question. In other words, it says nothing in regards to whether Gregory is dead or alive now.

Analogously, the past tense in (27b) refers to the past experience of the participants of the conversation with the vegan restaurant in question. Considering that there is no evidence that the vegan restaurant is closed now, the speakers can easily infer that it still exists, even though this is not part of the assertion.

An additional piece of evidence suggesting that the past tense morpheme in D-hani clauses like (27b) provides the evaluation time of the proposition comes from the following observation. Recall that D-hani clauses presuppose the truth of their prejacent. If the past tense in (27b) were not part of the proposition expressed in the prejacent, what would be taken for granted would be the proposition that there currently is a vegan restaurant at the location of speech. Therefore, a follow-up clause asserting that it does not exist anymore would sound contradictory. To illustrate, the example in (30) is infelicitous, because (30b) presupposes that there is a vegan restaurant at the location of speech, which excludes asserting that it does not exist.

In contrast, the version of (30b) with past tense is felicitous.

Hence, we argue that the hani clause in (27b) and (31b) presuppose that there was a vegan restaurant at the location of speech, and it remains vague as to its current existence. What it is not vague about is the past existence of the restaurant, which cannot be denied felicitously (see 32).

Let us now turn to the function of the past tense in Q-hani clauses. In the remainder of this section, we observe that the obligatory past tense morpheme occurring in them does not directly locate the eventuality of the preajcent at a past time, but it shifts the belief time of the speaker and addressee in the presupposition.Footnote 12 Given this, we predict that entertaining the possibility that the prejacent is false at the time of utterance does not lead to a contradiction unlike what we observed in D-hani clauses in (32). This prediction is also borne out, as illustrated in (33).

In Sect. 3.2, we show that the shift in the presupposition of hani results from a shift in the local context time at which the hani + prejacent is interpreted. The prejacent of hani being contained in this constituent is also affected by this shift.

The examples discussed so far involve non-verbal predicates. Before concluding this section, we would like to point out that the obligatoriness of the past tense morphology in Q-hani clauses extends to cases in which the predicate is verbal. Consider the examples in (34).

Notice that aspectual markes on verbal predicates are obligatory in Q-hani clauses. We consider this to lend morphological support to our conclusion that the past tense behaves differently in the two uses of hani. Indeed, aspect can be morphologically absent in D-hani clauses with verbal predicates marked with the past tense. This contrast is shown in (35).Footnote 13

In sum, in this section, we observed a sharp contrast between D-hani and Q-hani clauses in relation to the contribution of the past tense morphology. While the past tense is interpreted as expected in D-hani clauses, its contribution in Q-hani clauses is unusual. In the next section, we provide an analysis explaining the unexpected semantics of past tense in Q-hani clauses, after introducing our proposal for the semantics of hani in D-hani ones.

3 A compositional analysis of hani clauses

3.1 D-hani clauses

In the previous discussion, we concluded that D-hani clauses presuppose that speaker and addresee believe the prejacent to be true. We propose that this presupposition is encoded as a definedness condition in the lexical entry of hani as illustrated in (36).

We relativize the lexical entry of hani to the context of utterance, which we represent as a quintuple consisting of the context world (wc), context time (tc), the speaker in the context (sc), the addressee in the context (ac) and the assignment function (gc). These variables are used to refer to context variables throughout the paper.

According to (36), hani leaves the assertion unchanged and introduces the expressive presupposition that speaker and addressee of the conversation at the time of the conversation believe the prejacent to be true.

As an illustration, we provide below an example of a semantic computation of a D-hani clause, where we apply the lexical entry above.

Let us start by stating our basic semantic assumptions relative to a sentence without hani like (37a). We represent the structure of (37a) as in (37b).

In the interest of keeping our derivations simple, we skip some of the details of the internal composition of the proposition expressed by the prejacent. The reader should notice, however, that we assume that the sister of the tense head denotes a function from times to propositions (see (38b)). Moreover, we adopt Heim’s (1994) presuppositional rendition of Partee’s (1973) referential account of tense, as shown in (38a).Footnote 14

Now that we have laid out our basic theoretical assumptions, we can provide our analysis of D-hani clauses. We suggest that a D-hani clause minimally consists of a tensed proposition (contributed by the denotation of the prejacent) and hani.Footnote 15

In (40), we provide a sample derivation of the assertion and presuppositions for (39).

As desired, according to (40), a D-hani clause is true only if the prejacent is true and carries the presupposition that speaker and addressee of the context already believe at the time of utterance that the prejacent is true; it is undefined otherwise. Therefore, the meaning that we ascribe to hani captures the restrictions on D-hani clauses. First, hani is acceptable only in contexts where speaker and addressee believe the prejacent to be true (see the discussion in Sect. 2). Second, considering that the speaker chooses an item expressing the presupposition that the interlocutors of the conversation already believe the prejacent to be true, its assertive component is per se “uninformative”, in the sense that it does not add a new proposition to the CG. Given this, it can only be uttered in the presence of a relevant and novel continuation.

3.2 Q-hani clauses

We are now in the position to turn to our analysis of Q-hani clauses. Here, we present our three main assumptions regarding them. Their application to an example is in Sect. 3.3. As we pointed out in Sects. 1 and 2.3, in Q-hani clauses the past tense manipulates the belief’s time within the presupposition of hani. In order to derive this effect, our first assumption regards the structural position of the overt past tense morpheme at the LF of these clauses. Specifically, the past tense scopes above the entire hani clause, as shown in (41).

Our assumptions in regards to the interpretation of hani and the interpretation of the past tense are the same as introduced in the previous section. Specifically, the denotation of  is a proposition (〈s,t〉), whereas the past morpheme denotes a contextually salient time (of type i). This alone would lead to a type mismatch in (41). In order to resolve this mismatch and guarantee a shift in the belief’s time in the presupposition, our second assumption is the following. We suggest that the mismatch is resolved by the semantic rule given in (42), which has two main effects: (i) it generates from

is a proposition (〈s,t〉), whereas the past morpheme denotes a contextually salient time (of type i). This alone would lead to a type mismatch in (41). In order to resolve this mismatch and guarantee a shift in the belief’s time in the presupposition, our second assumption is the following. We suggest that the mismatch is resolved by the semantic rule given in (42), which has two main effects: (i) it generates from  a predicate abstract over the contextual time variable of

a predicate abstract over the contextual time variable of  , thus making it shiftable and (ii) it projects the presuppositions of the prejacent onto the larger constituent (see Santorio 2010 for a similar monstrous function application rule abstracting over gc).

, thus making it shiftable and (ii) it projects the presuppositions of the prejacent onto the larger constituent (see Santorio 2010 for a similar monstrous function application rule abstracting over gc).

Lastly, as mentioned above, in order to account for their challenging function, our proposal is to analyze Q-hani clauses as yes/no questions (see Sect. 2.2). Given this, we assume that their LF structure includes a silent whether or not, which we abbreviate as Q. This is shown in (43).

3.3 Formal implementation

In this subsection, we illustrate how the assumptions that we just laid out apply to a particular example. Before doing so, a brief discussion about the tense of the prejacent is at stake. Specifically, in assuming that the overt past morpheme scopes above hani, we do not intend to imply that the prejacent itself is tenseless. Tense in the prejacent is not absent; it is just unpronounced. Let us consider again the following example.

We argue that (44) is ambiguous between a present and a past prejacent as the glosses in (45a) and (45b), respectively, illustrate.

On the one hand, the fact that the present tense in the prejacent of (45a) is silent is unsurprising given that present tense in Turkish is unmarked, as illustrated in (46).

On the other hand, the interpretation in (45b) involving a second past morpheme that is not pronounced is less obvious. As stipulative as it might sound, the fact that a past tense morpheme is deleted at PF is not uncommon in Turkish. There are at least two other configurations in which this happens. The first consists of sentences involving the evidential marker -mIş. Consider the example below and its potential interpretations.Footnote 16

Crucially, under the past tense interpretation, Turkish cannot overtly mark the past tense morphology on the verb when it co-occurs with the evidential morpheme as shown in (48b).

The second case of past deletion is observed in counterfactual conditionals. Turkish marks counter-factuality with a past tense suffix, which comes right after the conditional suffix -sA.

Notice that (49) is ambiguous between a past and a present counterfactual reading, as its compatibility with dün ‘yesterday’ and şimdi ‘now’ shows. Crucially, disambiguation via an overt past marker on the antecedent predicate is ungrammatical, as shown in (50).

This is different from what happens in factual conditionals, where overt past marking on the predicate in the antecedent is not just possible but obligatory to express a past antecedent, as exemplified in (51).

The conditional data is in direct support of our claim that in Turkish, a past tense morpheme is deleted at PF when it co-occurs with another past tense morpheme in the same predicate, as in (45b).

Having established that in (44), repeated below in (52a), the tense of the prejacent can be past, let us turn to our illustration of the formal details of this case first. We will return to the present interpretation of the prejacent afterwards.

Since the constituent labelled  is identical to the one labelled

is identical to the one labelled  in the section on D-hani clauses, modulo the pronunciation of the past tense morpheme, its denotation is as given in (53), repeated from (40) above.

in the section on D-hani clauses, modulo the pronunciation of the past tense morpheme, its denotation is as given in (53), repeated from (40) above.

Due to the type mismatch mentioned above, the denotation of  is derived by the Monstrous Function Application proposed in (42), as shown in (55). The past tense denotation is repeated in (54) for convenience. Notice that what changes now is the contextual time at which the presupposition of hani + prejacent must hold, which is first bound (t′) and then applied to the past tense g(5).

is derived by the Monstrous Function Application proposed in (42), as shown in (55). The past tense denotation is repeated in (54) for convenience. Notice that what changes now is the contextual time at which the presupposition of hani + prejacent must hold, which is first bound (t′) and then applied to the past tense g(5).

As for the denotation of Q, we assume that it is a function that takes a proposition and returns the set of propositions including the argument and its negation.Footnote 17

Hence, applying the meaning of Q to the denotation of  via FA results in the meaning of

via FA results in the meaning of  , which, when defined, is a set of the propositions that Ali was in Istanbul and that Ali was not in Istanbul.

, which, when defined, is a set of the propositions that Ali was in Istanbul and that Ali was not in Istanbul.

In prose,  is defined if and only if at a time previous to the utterance (i.e., at g(5)), speaker and addressee believed that Ali was in Istanbul at a time previous to those beliefs (i.e., at g(4)). When defined, it is equivalent to the yes/no question Was Ali in Istanbul?. Noticeably, the context time parameter of the hani presupposition is locally shifted to the past by the past tense morpheme scoping over hani.

is defined if and only if at a time previous to the utterance (i.e., at g(5)), speaker and addressee believed that Ali was in Istanbul at a time previous to those beliefs (i.e., at g(4)). When defined, it is equivalent to the yes/no question Was Ali in Istanbul?. Noticeably, the context time parameter of the hani presupposition is locally shifted to the past by the past tense morpheme scoping over hani.

According to the analysis, when the prejacent is past, the time of the prejacent (g(4)) precedes the time of the belief that the prejacent is true (g(5)), which in turn precedes the utterance time (tc). Let us illustrate this with a concrete example. The relationship between the event time (ET) and belief time (BT) relative to the utterance time (UT) is illustrated in the timeline in (58b).

We can now turn to the other interpretation of (44), that is the interpretation where the unpronounced tense in the prejacent is intended to be the present tense.  below stands for the logical form, which is identical to the one in (52), except that the lower past is replaced with the present. This reading only differs from (57) in that the relation between g(4) and g(5) is the overlap relation here.

below stands for the logical form, which is identical to the one in (52), except that the lower past is replaced with the present. This reading only differs from (57) in that the relation between g(4) and g(5) is the overlap relation here.

The predicted difference between the two cases (past prejacent and present prejacent) is not straightforward. According to our analysis, the time of the eventuality in the prejacent (i.e., g(4)) is related to a context time g(5) that is shifted to the past by the higher past in both cases. It is prior to it if the tense in the prejacent is past (g(4) < g(5); see (57)) and overlapping with it if it is present (g(4) ∘ g(5); see (59)). Given this, in both cases the prejacent eventuality is past relative to the utterance time tc. However, the two readings make distinct predictions in adequately construed scenarios such as the following one.

According to the analysis presented here, if the tense in the prejacent was past (i.e., if g(4) preceded g(5), (60b) would be undefined. Here is why. In that case the sentence would presuppose that speaker and addressee believed that Ali was in the office at some time preceding the time at which they believed so (i.e., preceding the phone call). This presupposition is not satisfied in (60a), since Ali guarantees his presence in the office at the very time of the phone call and not before it (he might very well be just stepping in as he talks on the phone with Zeynep). Since (60b) is instead perfectly felicitous and natural, we can conclude that the prejacent in it contains a silent present morpheme. The presupposition is then that Ali’s presence in the office overlaps with the past time of the speaker and addressee’s belief that he was, and this presupposition is indeed satisfied in (60a).

Thus far, we have seen that the prejecant tense can be past or present. The other aspect of the analysis is that the past and present tense in the prejacent are not construed relative to the utterance time but relative to the locally shifted context time (that is the belief’s time). A potential competing analysis, as indicated by one of the anonymous reviewers, where the prejacent tense remains unbound and is interpreted directly in relation to the highest UT, leads to incorrect predictions as it would generate a presupposition that is too weak. Consider for example a case where the eventuality of the prejacent is located between the belief time and utterance time like (61a).

The competing view of the prejacent tense relativized to the utterance time would incorrectly predict (61b) to be felicitous, regardless of the value of the silent tense (present or past). In the case of a present interpretation of the silent tense in the prejacent, due to the aspect of anteriority introduced by -mIş, the event could precede the utterance time. But, lacking a relation with the belief time, it may follow the latter as in (61c). Accordingly, (61b) would presuppose simply that both the belief time and event time precede UT regardless of their order. Evidently, (61a) satisfies this presupposition.

Similarly, if the prejacent tense is past, the mere requirement in the presupposition of (61b) would be that both ET and BT precede UT, in any respective order. Once again, this presupposition is too weak because it is satisfied in (61a) although (61b) is infelicitous.

What this example shows is that a relation of overlap or precedence relative to the belief time is crucial to capture the intuitions of the felicity of Q-hani clauses. Their relation with the utterance time is only mediated via the shifted belief time. This guarantees a presupposition strong enough to account for the facts.

Since our analysis where the MFA rule effectively binds the prejacent tense and makes it shiftable to the past of the belief time, it correctly predicts the infelicity of (61b) in contexts like (61a). If the tense of the prejacent is present, the anterior aspect -mIş locates the event prior to the locally shifted context time, that is the shifted belief time. The resulting presupposition would then be that Ali arrived at the office at some time (ET) preceding Mehmet’s belief that he did (BT). However, as indicated in (61a) and (61c), BT precedes the ET, hence the presupposition failure.

Likewise, if the time of the prejacent were past, the local context shift would locate the ET prior to the BT, which is again not satisfied in the context in (61a).

Given that our MFA rule + wide scope of the overt past make the correct empirical predictions even in contexts such as (61a), we conclude that in Q-hani clauses not only the belief time is shifted, but also the event time is affected by the local context shift.

The data presented above clearly indicate that shifting the local context time of the prejacent makes correct predictions. However, we would like to point out that only examples involving non-stative verbal predicates can tell apart our view from the opposing view just discussed. This is because non-verbal predication in Turkish can receive a future interpretation, as shown in (62).Footnote 18

Given this, the Q-hani clause in (63b) may ask a question relative to an eventuality located at UT (that is following BT) in a context like (63a).Footnote 19

Given that the silent present morpheme of the prejacent in (63b) may be interpreted as future relative to the BT, this example does not necessarily indicate that the tense of the prejacent is present relative to the UT.Footnote 20 Therefore, such data do not constitute a counterexample to the tense shift of the prejacent in Q-hani clauses.

4 Deriving the properties of Q-hani clauses

Having introduced the details of our analysis, in this section, we discuss how it accounts for some of the peculiar properties of Q-hani clauses.

4.1 Distribution of Q-hani clauses

Recall that Q-hani clauses are infelicitous in contexts like the one below.

Our analysis predicts the infelicity of (64b) because in this context, the definedness condition that speaker and addressee both previously believed that there was a vegan restaurant in their surrounding is not satisfied. This results in a presupposition failure.

Our analysis also predicts that Q-hani clauses are expected to be felicitous as long as their presupposition about past beliefs is satisfied in their context of utterance. That is, the past beliefs do not have to be formed as a result of a linguistic assertion, but can result from extra linguistic information, as shown in (65).

Instead, if the belief is understood to be non-mutual in the sense of Stalnaker (2002), a Q-hani clause is inappropriate as expected.

The above discussion clearly shows that Q-hani clauses do not require a previous assertion to be able to pick up the content of the belief, but the past belief that the prejacent was true must be mutual.

4.2 Challenging uses of Q-hani clauses

In this section, we illustrate the components of our analysis that address the apparent challenging function of Q-hani clauses. Specifically, by uttering a Q-hani clause, the speaker expresses her disbelief regarding the prejacent (due to current counter-evidence) and requires from the addressee to choose between the following two reactions. Either convince the speaker to reject the counter-evidence (yes answer) or accept the prejacent is false (no answer). An example of this effect is provided in (67).

The ingredient of our analysis that we believe to be responsible for the effect of scepticism described above is an implicature triggered by the past tense in the presuppoisiton of Q-hani clauses. First, let us illustrate what this implicature would look like.

In the literature on implicatures, the past tense has been argued to trigger the implicature that what the proposition conveys is not currently true. The example in (68), which is from Chierchia and McConnell-Ginet (1990), is an illustration.

We suggest that the shifting of the presupposition to the past in Q-hani clauses results in a similar implicature; that is, that the speaker and addressee no longer believe that the prejacent is true. (69) is a simplified calculation of this implicature. To simplify the discussion, assume temporarily that the presupposition is an utterance (U). A below stands for alternatives. K stands for ‘speaker of U knows’, and p stands for the prejacent.

Importantly, the implicature we derive is not that the prejacent is false, but that the participants of the conversation currently fail to believe that it is true. Thus, the presupposition related to the past CG implies that the current one does not contain the prejacent anymore, not that it contains its negation.

In our Q-hani examples, (69i) is not uttered overtly, but presupposed. This, we claim, is a case where an implicature is computed from a presupposition. Cases of this sort are not unheard of. Indeed, Ippolito (2003) derives the intuition of the falsity of the antecedent in counterfactual conditionals from an implicature of the presupposition of the past morpheme. The relevant examples are of the form in (70). Ippolito’s (2003) claim is that the overt past tense shifts the time of the accessibility relation of the conditional (also a context-dependent item!), and this generates the negative implicature of counterfactuality. For details, we refer the reader to Ippolito (2003).

To conclude, Q-hani clauses come with an ignorance implicature relative to the current truth of the prejacent, which, in combination with the questioning of the prejacent, generates the effect of uncertainty and scepticism the speaker conveys with these sentences.

4.3 Considerations on liability

In a very frequent of their uses, Q-hani clauses appear to be intended as to hold one’s addressee responsible for the speaker’s belief that the prejacent is true. Indeed, oftentimes they provide the inference that the addressee previously lied to the speaker regarding its truth. Does the question analysis of Q-hani clauses account for this inference? We argue that it does in the following way.

Generally speaking, a proposition p can be added to the CG of the interlocutors a and b if a asserted p, and b accepted it; or if b asserted p, and a accepted it; or if a third person c asserted p, and both a and b accepted it. Now, imagine a scenario where a asserts p, and b accepts it, but a later learns that p is not true. Can a utter a Q-hani clause to hold herself liable for adding p in the CG? The question analysis that we have presented predicts that she cannot. The reason is that if a learned that p is actually not true, it would be inappropriate for a to ask the addressee whether p is true. Furthermore, since it was a that asserted p in the first place, it would be odd for her to request an answer from her addressee with respect to the truth of p. This prediction is borne out as illustrated in (71).Footnote 21

However, if it were b that asserted p in the first place, and a accepted it, then based on a’s subsequent evidence against p, she could utter a Q-hani clause so as to express that she considers b liable for mistakenly asserting p.

Here is how b’s liability in (72) is derived. In this example, the speaker asks a question which presupposes that she and her addressee had believed that Ali would be in the office all day, while asking whether this is actually true. Crucially, in our context the speaker believed this information to be true due to the addressee’s previous assertion. Recall that in order to ask such a question, the speaker must have later encountered evidence challenging the truth of the prejacent. Hence, the speaker suspects that that her addressee lied. This causes the addressee to be held responsible for causing p to be mistakenly added to the CG and owing an explanation.

Importantly, the above inference of liability is contextually derived, and therefore not a necessary component of Q-hani clauses. One can easily find uses of Q-hani clauses where the addressee is not responsible at all for adding p in the CG. These are cases where speaker and addresse come to believe that p is true because of an utterance of a third party. Our analysis predicts that in those cases, Q-hani clauses would simply question the truth of p without an inference of liability, as illustrated in (73).

As is the case in any other contexts, uttering a Q-hani clause in the context provided in (73a) comes with the implicature that the speaker has ceased to believe p (=that it is an afternoon off), which is reasonable given the secretary’s behaviour. However, the speaker obviously does not hold his addressee liable for adding p in the CG, since it was not the secretary that was responsible for Ahmet previously believing it. (73b) simply implies that the speaker does not believe p anymore, and asks for confirmation of this implicature.

5 Previous approaches and their shortcomings

This section is a brief critical review of the only previous approach to hani, that is Akar and Öztürk (2020) and Akar et al. (2020). These authors point out that hani clauses are similar in meaning and use to English negative polar questions (NPQs).

According to Ladd (1981), these questions are systematically ambiguous between a reading where negation applies to the proposition in the proto-question (inner negation) and a reading where it takes a wider scope (outer negation). Accordingly, a question like (74a) below may have either of the two different pragmatic functions in (74b) and (74c), depending on whether the negation is interpreted as “outer negation” or “inner negation”, respectively.

Subsequent work argues that English negative polar questions are biased either towards the positive or negative answer (Van Rooy and Safarova 2003, Romero and Han 2004, Reese 2005, Krifka 2017). Specifically, when negation is outer negation, the speaker is biased towards the positive answer, but wants confirmation for it. Conversely, with inner negation, the speaker tends towards the negative answer, but wants confirmation for it (Krifka 2017, 2015).Footnote 22

Akar et al. (2020) and Akar and Öztürk (2020) draw a parallelism between D-hani clauses and polar questions with outer negation, and between Q-hani clauses and polar questions with inner negation. However, we observe that hani clauses display a more limited distribution than negative polar questions, and the similarities are limited to their pragmatic functions in the very contexts and scenarios where negative questions and hani clauses are both acceptable. In fact, there are contexts where a D-hani clause is not felicitous, whereas a negative question with outer negation is.

Whereas Akar et al. (2020) and Akar and Öztürk (2020) fail to predict the contrast in (75), the latter finds a straightforward explanation in the account presented in this paper. As argued previously, D-hani clauses carry the presupposition that both speaker and addressee believe the prejacent to be true; however, the addressee in (75c) cannot possibly believe that she read it if she actually did not, hence the presupposition failure and the infelicity of (75c).

Similarly, there are contexts where NPQs with inner negation are natural and acceptable, but Q-hani clauses are not.

Since in (76c), Ahmet seeks confirmation that there is no vegan restaurant nearby, the negation in it is interpreted as inner negation. The infelicity of (76c) follows from our analysis because Ahmet’s uttering a Q-hani clause in this context results in a presupposition failure, since Ayşe’s statement by itself denies her belief that the prejacent of (76c) is true.

The facts discussed in this section show that hani clauses are not fully parallel to NPQs, and therefore a unified semantic analysis of the two would be misleading. This being said, we do not deny that they sometimes naturally overlap in their uses (see Akar et al. 2020, Akar and Öztürk 2020), and this is why in many cases it is natural to translate hani clauses as NPQs. We do not discuss in detail why in certain contexts both hani clauses and NPQs are licensed. Possibly, this is because they both generate an effect of speaker’s bias towards a proposition. Hani clauses additionally require the addressee’s belief towards it, whereas NPQs do not appear to. We leave a formal investigation of the relationship between NPQs and hani clauses to future research.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper proposes the first unified compositional analysis of hani clauses that accounts for their different pragmatic functions and distributional restrictions. These differences are derived from structural differences, whereas the contribution of hani is taken to be constant. The analysis relies on the assumption that contextual parameters may be available for further manipulation in the truth conditional composition of meaning, and we take this to reflect cross-linguistic variation, where these types of semantic mechanisms may or may not be available in a given language.

One main issue we are leaving to further research is the obligatory presence of the past tense morpheme in what we dubbed Q-hani clauses. At this stage we can only offer some general speculations as to why this should be the case. In the absence of the past shift of the presupposition of hani in those interrogative clauses, they would end up presupposing that sc and ac believe the prejacent to be true at the utterance time and ask whether it is. This itself might be unacceptable, as the negative answer would generate a contradiction with the presupposition, while the positive answer left to the addressee as the only option would be equivalent to the corresponding D-hani clause. From the viewpoint of the questioner, we find that requesting the answerer to assert a D-hani clause with the same prejacent as the question is not pragmatically a legitimate move.

One more issue that still needs to be addressed concerns the phonological prominence on hani in Q-hani clauses (but not in D-hani clauses). Previous researchers have likened this to the phonological behavior of wh-words in Turkish matrix constituent questions (see Göksel et al. 2009), citing the intriguing fact that hani is historically a wh-word (Akar and Öztürk 2020, Akar et al. 2020). Although in general LF-PF mismatches are predicted in the Y models of grammar (Chomsky 1995), our analysis of Q-hani clauses as yes/no questions may seem at odds with the observation that Q-hani clauses appear to have a wh-question like contour with hani bearing phonological prominence. We speculate that hani bearing phonological prominence can be explained by the additional piece in the syntax of Q-hani clauses, namely the Q morpheme. It could well be that the phonologically prominent hani, i.e., hani, is a portmanteau exponent that realizes both hani and the Q morpheme. While the Q morpheme is normally realized by the mI particle in matrix questions, realizational theories of morphology easily predict that a portmanteau form will bleed a competing bi-morphemic realization. In other words, the fact that Q-hani clauses not featuring mI is on a par with the portmanteau form went in English bleeding the bi-morphemic form *go-ed.

Notes

Extending common practice on intensional operators, we call the sister of hani at LF its prejacent.

This paper leaves out a couple of other additional uses of hani, which we believe are not immediately related to the two main ones that we investigate here. First, in some very restricted occurrences, hani appears to mean nerede ‘where’. Secondly, it is often used as a “filler”, such as ‘I mean, um, er’ (see Özbek 1995, 1998, Furman and Özyürek 2007 for a discussion on “fillers” in Turkish). Finally, it is also used in child-directed speech to draw their attention to an object. Whether or not these uses can fall under a unified analysis is a question that we leave for future research.

In fact, a variant of (1a), that is also acceptable, is one where hani is unpronounced but ya is present. We take this case to be identical to (1a), where ya signals the presence of hani.

We thank one of the anonymous reviewers for bringing this point to our attention.

Hani clauses associated with the reminding function presented in (1a) have been reported to have a declarative intonation in the absence of ya, whereas they have been claimed to exhibit polar question intonation in the presence of ya (Akar and Öztürk 2020, Akar et al. 2020). Our intuitions concerning the intonation of hani clauses with ya is that it is similar to, but not identical to the intonation pattern found in yes/no questions. However, we do not undertake the task of determining their phonological properties and leave the comparison to future research.

A reviewer suggests to apply von Fintel’s (2004) ‘Hey, wait a minute test!’ to provide an additional argument for the presence of the presupposition of hani clauses. However, this test is not intended to test the existence of a presupposition, but to distinguish presuppositions from assertions in what is conveyed by a sentence, where these two might be confused.

We thank an anonymous reviewer who suggests a potential additional linguistic test to demonstrate the restriction that D-hani clauses occur with a follow-up utterance that picks up on their content. This finding is in support of our generalization in Sect. 2.2 that D-hani clauses are stage openers, always being followed by another utterance. Specifically, the reviewer suggests that the discourse particle Ee? ‘So?’ could be a felicitous reply to a D-hani clause uttered in isolation, further demonstrating this restriction of D-hani clauses. In addition, they point out that obvious utterances (part of CG), when occuring in isolation, legitimize the use of Ee?. Although we agree with the reviewer’s intuitions, we believe that the function of Ee? is more general. According to our informants, Ee? is felicitious when following any conversational pause that seems out of place, perhaps too long. In a sense, Ee? is a remark conveying that it is not yet the time for turn-taking in the conversation, asking the speaker for a continuation. Given this general function of Ee?, it makes sense that it would be a felicitous response to a D-hani clause uttered in isolation.

We use quotational embedding because hani clauses are otherwise non-embeddable.

We thank one of the anonymous reviewers for suggesting this test.

The comment “What kind of question is this?” can target the initial question, even when the speaker’s last utterance is a declarative sentence. This is shown in (i).

-

(i)

-

(i)

This assumption might be challenged as the intonational contour of these clauses is typical of Turkish wh-questions (Göksel et al. 2009). However, mismatches between form and meaning of this sort are predicted in a Y model theoretic view of grammar (Chomsky 1995). Mismatches are addressed in interfaces of the grammar: (i) by realizations rules in the morphology component (Halle and Marantz 1993) and (ii) by LF operations in the logical component (Heim and Kratzer 1998).

We show in Sect. 3 that the shift in the presupposition time has an effect on the time of the prejacent.

Due to the additional complexity of the verbal predicates in Q-hani clauses, our sample calculations involve sentences with non-verbal predicates, as an analysis of aspect is not crucial to the claims of this paper.

Besides the referential anaphoric view that we adopt above, there is another main view on the semantics of past where it introduces an existential quantification with contextual domain restrictions (see Ogihara 2007). Our proposal is compatible with the existential quantification view of the past tense proposed by Ogihara (2007) as well.

Given that the particle ya is optional, we do not include it in our structural representation. One might treat it as an identity function over propositions.

-mIş exhibits a curious behavior in Turkish. When it follows non-verbal predicates and aspectually marked verbs, it is an evidential marker, as shown in (47), whereas it marks anterior aspect when it precedes a tense morpheme. We remain agnostic as to whether the two meanings of -mIş should be related or are independent entries in the lexicon.

In Karttunen (1977), this is achieved in two steps: by the meaning of a Q morpheme, and the meaning of whether-or-not. We combined the two in one lexical item in the interest of simplicity.

The same also applies to the progressive marker in Turkish. It not only has a present time reference, but can also refer to a future time like the English progressive.

Notice that the example in (63) is different from (60), where the event and belief times overlap. Crucially, in (63), the belief time is prior to the event time.

One of the anonymous reviewers asks whether the examples arguing for null present and past tenses in the prejacent could also be analyzed to host a non-future tense as suggested in Matthewson for St’át’imcets. We believe that this would not work for Turkish for a number of different reasons. First, in St’át’imcets, predicates unmarked for tense in matrix clauses can have present or past temporal reference, but crucially cannot denote future events, which are overtly marked. Differently from St’át’imcets, past tense has to be marked in matrix clauses in Turkish, while the present tense is unmarked. Hence, one cannot talk about a two-way distinction involving future and non-future for Turkish matrix clauses. Second, it is not true that Q-hani clauses cannot have a future interpretation in the prejacent in the absence of future marking. This is in sharp contrast with St’át’imcets. Indeed, examples like (63b) and (62) show that the prejacent can have a future interpretation (relative to the belief time) without any overt marking.

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, a polar question without hani would also be odd in the same context as (71a). This supports our proposal that Q-hani clauses are indeed questions.

For the details relating to bias in NPQs, see the cited references above.

References

Akar, D., and B. Öztürk. 2020. The discourse marker hani in Turkish. In Information-structural perspectives on discourse particles, eds. P. Y. Modicom and O. Duplâtre, 251–276. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Akar, D., B. Öztürk, A. Göksel, and M. Kelepir. 2020. Common ground management and inner negation in one: The case of hani. In Discourse meaning, eds. D. Zeyrek and U. Özge, 57–78. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Aygen, G. 2007. Q-particle. Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi (Journal of Linguistics and Literature) 4(1): 1–30.

Chierchia, G., and S. McConnell-Ginet. 1990. Meaning and grammar: An introduction to semantics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Coniglio, M. 2007. German modal particles in the IP-domain. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 32: 3–37.

Deal, A. R. 2020. A theory of indexical shift: Meaning, grammar, and crosslinguistic variation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Döring, S. 2016. Modal particles, discourse structure and common ground management: Theoretical and empirical aspects. PhD dissertation, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Döring, S., S. Repp, S. Featherston, R. Hörnig, S. Von Wietersheim, and S. Winkler. 2019. The modal particles ja and doch and their interaction with discourse structure: Corpus and experimental evidence. In Experiments in focus: Information structure and semantic processing, eds. S. Featherston, R. Hörnig, S. von Wietersheim, and S. Winkler, 17–55.

Eckardt, R. 2016. Questions on the table. Unpublished manuscript. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304304651_Questions_on_the_Table.

Egg, M., and M. Zimmermann. 2012. Stressed out! Accented discourse particles: The case of ‘doch’. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 16, eds. A. Aguilar Guevara, A. Chernilovskaya, and R. Nouwen, 225–238.

Erguvanlı-Taylan, E. 2000. Semi-grammaticalised modality in Turkish. In Studies on Turkish and Turkic languages; proceedings of the ninth international conference on Turkish linguistics, eds. A. Göksel and C. Kerslake, 133–143.

Farkas, D. F., and K. B. Bruce. 2009. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics 27(1): 81–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffp010.

von Fintel, K. 2004. Would you believe it? The king of France is back! (Presuppositions and truth-value intuitions). In Descriptions and beyond, eds. A. Bezuidenhout and M. Reimer, 315–341. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Furman, R., and A. Özyürek. 2007. Development of interactional discourse markers: Insights from Turkish children’s and adults’ oral narratives. Journal of Pragmatics 39(10): 1742–1757.

Gajewski, J. 2002a. L-analyticity and natural language. Unpublished manuscript. https://jon-gajewski.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1784/2016/08/analytic.pdf.

Gajewski, J. 2002b. L-triviality and grammar. Unpublished manuscript. https://jon-gajewski.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1784/2016/08/Logic.pdf.

Gazdar, G. 1979. Pragmatics, implicature, presuposition and logical form. Critica 12(35).

Göksel, A., M. Kelepir, and A. Üntak-Tarhan. 2009. Decomposition of question intonation: The structure of response seeking utterances. In Phonological domains, eds. J. Grijzenhout and B. Kabak, 249–282. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Grice, H. P. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Speech acts, eds. P. Cole and J. L. Morgan, 41–58. Leiden: Brill.

Groenendijk, J. 1999. The logic of interrogation: Classical version. In Semantics and linguistic theory 9, eds. T. Matthews and D. Strolovitch, 109–126.

Groenendijk, J., and M. Stokhof. 1984. Studies on the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

Gutzmann, D. 2009. Hybrid semantics for modal particles. Sprache und Datenverarbeitung 33(1–2): 45–59.

Gutzmann, D. 2013. Expressives and beyond: An introduction to varieties of conventional non-truth-conditional meaning. In Beyond expressives: Explorations in use-conditional meaning, Leiden: Brill.

Halle, M., and A. Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20, MIT working papers in linguistics, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heim, I. 1991. Artikel und definitheit. Temantik: ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung 5(6): 487–535.

Heim, I. 1994. Comments on Abusch’s theory of tense. In Ellipsis, tense and questions, 143–170.

Heim, I., and A. Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ippolito, M. 2003. Presuppositions and implicatures in counterfactuals. Natural Language Semantics 11(2): 145–186.

Kamali, B., and M. Krifka. 2020. Focus and contrastive topic in questions and answers, with particular reference to Turkish. Theoretical Linguistics 46(1–2): 1–71.

Kaplan, D. 1989. Demonstratives: An essay on the semantics, logic, metaphysics and epistemology of demonstratives and other indexicals. In Themes from Kaplan, eds. J. Almog, J. Perry, and H. Wettstein, 481–563. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Karagjosova, E. 2004. The meaning and function of German modal particles. Unpublished manuscript.

Karttunen, L. 1977. Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics & Philosophy 1: 3–44.

Kratzer, A. 1995. Stage-level and individual-level predicates. In The generic book, eds. G. N. Carlson and F. J. Pelletier, 125–175. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kratzer, A. 1999. Beyond ouch and oops: How descriptive and expressive meaning interact. In Handout for Cornell conference on theories of context dependency. https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/WEwNGUyO/Beyond%20%22Ouch%22%20and%20%22Oops%22.pdf.

Kratzer, A. 2004. Interpreting focus: Presupposed or expressive meanings? A comment on Geurts and van der Sandt. Theoretical Linguistics 30(1): 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.2004.002.

Krifka, M. 2001. Quantifying into question acts. Natural Language Semantics 9: 1–40.

Krifka, M. 2011. Questions. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. K. von Heusinger, C. Maienborn, and P. Portner, 1742–1785. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Krifka, M. 2015. Bias in commitment space semantics: Declarative questions, negated questions, and question tags. In Semantics and linguistic theory 25, 328–345.

Krifka, M. 2017. Negated polarity questions as denegations of assertions. In Contrastiveness in information structure, alternatives and scalar implicatures, eds. S. D’Antonio, M. Moroney, and C. R. Little, 359–398. New York: Springer.

Ladd, D. R. 1981. A first look at the semantics and pragmatics of negative questions and tag questions. In Proceedings of the Chicago linguistics society 17, eds. R. A. Hendrick, C. S. Masek, and M. F. Miller, 164–171.

Matthewson, L. 2006. Temporal semantics in a superficially tenseless language. Linguistics and Philosophy 29: 673–713.

Musan, R. 1997. Tense, predicates, and lifetime effects. Natural Language Semantics 5(3): 271–301.

Ogihara, T. 2007. Tense and aspect in truth-conditional semantics. Lingua 117(2): 392–418.

Özbek, N. 1995. Discourse markers in Turkish and English: A comparative study. PhD dissertation, University of Nottingham.

Özbek, N. 1998. Türkçede söylem belirleyicileri. Dilbilim Araştırmaları Dergisi 9: 37–47.

Özyıldız, D. 2015. Move to mI, but only if you can. In Workshop on altaic formal linguistics 11, 4–6.

Partee, D. 1973. Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns in English. The Journal of Philosophy 70(18): 601–609.

Reese, B. 2005. Negative polar interrogatives and bias. In New frontiers in artificial intelligence: Joint JSAI 2005 workshop post-proceedings, eds. T. Washio et al., 85–92.

Rojas-Esponda, T. 2014. A QUD account of German ‘doch’. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 18, eds. U. Etxeberria, A. Fălăuş, A. Irurtzun, and B. Leferman, 359–376.

Romero, M., and C. Han. 2004. On negative yes/no questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 27(5): 609–658.

Santorio, P. 2010. Modals are monsters: On indexical shift in English. In Semantics and linguistic theory 20, eds. N. Li and D. Lutz, 289–308.

Sauerland, U. 2007. Beyond unpluggability. Theoretical Linguistics 33(2): 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.016.

Schlenker, P. 2003. A plea for monsters. Linguistics and Philosophy 26(1): 29–120.

Schlenker, P. 2007. Expressive presuppositions. Theoretical Linguistics 33(2): 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.017.

Stalnaker, R. 1977. Pragmatic presuppositions. In Proceedings of the Texas conference on per˜ formatives, presuppositions, and implicatures, eds. M. K. Munitz and P. Unger, 135–148. Arlington: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Stalnaker, R. 1978. Assertion. In Pragmatics, ed. P. Cole, 315–332. Leiden: Brill.

Stalnaker, R. 1999. Context and content: Essays on intentionality in speech and thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Stalnaker, R. 2002. Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy 25(5/6): 701–721.

Van Rooy, R., and M. Safarova. 2003. On polar questions. In Semantics and linguistic theory 13, 292–309.

Zimmermann, M. 2012. Discourse particles. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. K. von Heusinger, C. Maienborn, and P. Portner, 2012–2038. Berlin: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110255072.2012.

Acknowledgements

For very valuable feedback, we thank the two NALS anonymous reviewers and the editors. We are also grateful to Didar Akar, İsa Kerem Bayırlı, Balkız Öztürk, Nilüfer Şener and the audiences of the 8th Workshop on Turkic and Languages in Contact with Turkic and of the Jezik and Linguistics Colloquium at the University of Nova Gorica for their constructive comments. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dikmen, F., Guerzoni, E. & Demirok, Ö. When tense shifts presuppositions: hani and monstrous semantics. Nat Lang Semantics 32, 231–268 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09215-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09215-y