Abstract

This article develops a comparative semantic analysis of representative focus-alternative quantifiers in English and Japanese: (i) only in English, (ii) dake, dake-wa, and shika in Japanese, and (iii) the cleft construction(s in the two languages). A sentence with only typically, and one with shika invariably, conveys the “negative contribution (NC)” (exclusivity implication) as an at-issue content and the “positive contribution (PC)” (prejacent-proposition) as a (non-presuppositional) not-at-issue content. A sentence with dake typically conveys both PC and NC as at-issue contents, while a sentence with dake-wa, as well as the cleft construction, conveys the PC as an at-issue content and the NC as a not-at-issue content. Dake-wa and the cleft semantically contrast in two respects: (i) with the former, the NC is presuppositional, while with the latter it is non-presuppositional, and (ii) only the latter conveys, as a presupposition, that at least one of the relevant alternative propositions holds true. With appropriate contextual cues, only may receive the dake-like, symmetrical interpretation. Dake may receive, in limited configurations, the dake-wa-like interpretation where only the PC is at-issue. These findings contribute to the general-linguistic taxonomy of focus-alternative quantifiers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This article develops a comparative semantic analysis of representative exclusive focus-alternative quantifiers in English and Japanese, aiming to deepen our understanding of how natural languages may contrast with each other in how to encode exclusivity.

The meaning of a sentence with an exclusive focus-alternative quantifier (focus-sensitive operator), such as only, has two components. With van Rooij and Schulz (2007), I will refer to them as (i) the Positive Contribution (PC) and (ii) the Negative Contribution (NC).

-

(1)

Only [Ken]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) left.

-

a.

PC ≈ “Ken left.”

-

b.

NC ≈ “Nobody other than Ken left.”

-

a.

Following Velleman et al. (2012), I consider the it-cleft to be an exclusive focus-alternative quantifier, too.

-

(2)

It was [Ken]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who left.

-

a.

PC ≈ “Ken left.”

-

b.

NC ≈ “Nobody other than Ken left.”

-

a.

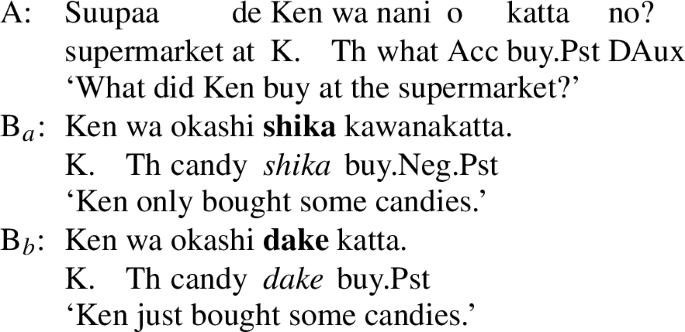

Japanese has three exclusive particles, (i) dake, (ii) dake-wa, and (iii) shika(+Neg), the semantic differences of which have been a matter of some debate. (3a, i), (3a, ii) and (3b) all convey that Ken left (PC) and that nobody other than Ken left (NC).Footnote 1

-

(3)

These particles typically occur on complement nominals and adverbials. Dake-wa formally consists of two particles, dake and wa. The two components are hyphenated here merely for an expository purpose, without presupposing their forming a single complex or compound particle. Shika obligatorily occurs with a clause-mate negation, and induces the exclusive meaning in conjunction with the negation.

Japanese furthermore has a cleft construction (Cho et al. 2008; Hiraiwa and Ishihara 2012), which I refer to as the no-cleft for convenience.

-

(4)

The no-cleft appears to be by and large synonymous to the it-cleft, and I will assume that the analysis of the latter discussed below carries over to the former. On the other hand, how the meanings of dake, dake-wa, and shika contrast with one another and with that of only is a rather intriguing issue. (5a) involves an instance of only that is most appropriately translated with dake, and (5b) involves one that is most appropriately translated with shika(+Neg).

-

(5)

-

a.

(Context: Ken, Toru, and Masaki are competing in a round-robin chess tournament with 10 participants. The three of them are tied in the first place, each with seven wins and two losses. They will have their last match today, each playing against a different opponent.)

If only Ken wins, he will be the champion.

-

b.

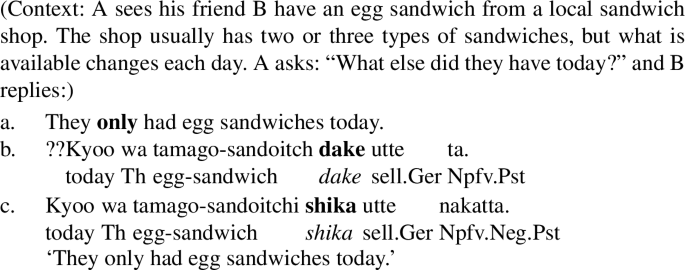

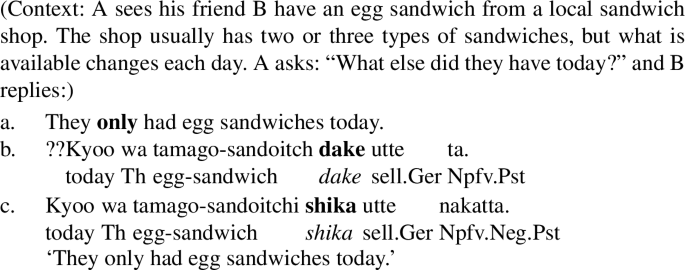

(Context: A sees his friend B have an egg sandwich from a local sandwich shop. The shop usually has two or three types of sandwiches, but what is available changes each day. A asks, “What else did they have today?” B replies:)

They only had egg sandwiches today.

-

a.

-

(6)

-

(7)

A key difference between (5a) and (5b) is that neither PC nor NC is contextually assumed to hold true in the former, while the PC is contextually assumed to hold true in the latter. These examples will be revisited in due course.

The current work is structured as follows. Section 2 puts forth the baseline analyses of only and the cleft, building on Beaver and Clark (2008); Coppock and Beaver (2011); and Velleman et al. (2012), according to which an only-sentence and a cleft share the same NC that amounts to saying that the prejacent-proposition is an exhaustive, or maximally informative, answer to the contextually prominent question.

Section 3 discusses how the three Japanese exclusive particles contrast with each other in terms of at-issue/not-at-issue (proffered/non-proffered) configurations. With a shika-sentence, the PC is not-at-issue (non-proffered, backgrounded), while with a dake-wa-sentence, the NC is not-at-issue. With a dake-sentence, both PC and NC are at-issue (proffered, foregrounded). Section 4 discusses how English only, when pragmatically coerced, allows the dake-like, “dual-foregrounded” interpretation, implying that the so-called symmetrical approach to the meaning of only is not to be entirely dismissed.

Section 5 takes a closer look at the nature of the not-at-issue content of a sentence with an exclusive quantifier. It will be pointed out that the NC of a dake-wa-sentence is presuppositional, whereas the PC of an only-sentence (on its typical, asymmetrical reading), the PC of a shika-sentence, and the NC of a cleft are non-presuppositional. Section 6 discusses how the choice between dake-wa and the cleft, which have similar meanings, is made in different discourse configurations. Section 7 briefly discusses how the meaning of dake-wa might be related to the meaning of wa as an independent particle.

The English and Japanese data discussed in the current work are constructed by the author, except for the examples quoted (possibly with slight adaptations) from the cited sources. The acceptability judgements on the constructed Japanese examples are based on the author’s native speaker intuition. Those on the constructed English examples are based on the author’s intuition, and were checked by at least one native speaker consultant.

2 Only and the cleft: The baseline analyses

Building on the question-based theory of focus (Roberts 1996, 2012; Büring 2003; Velleman and Beaver 2014), Beaver and Clark (2008) and Coppock and Beaver (2011) argue that only has a meaning along the lines of (8), where (i) materials between curly braces {⋅} represent not-at-issue, or projective (Tonhauser et al. 2013), contents; and (ii) CQ represents the current question—the contextually prominent question immediately addressed by the interlocutors in the discourse.Footnote 2

-

(8)

only ↦ λp[λw[{p(w)}[max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w)]]]

-

(9)

max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p) =\(_{def}\) λw[¬∃q∈CQ[[q⊂p] & q(w)]]

-

(10)

〚{ϕ}[α]〛 is defined only if 〚ϕ〛 = 1; if defined, 〚{ϕ}[α]〛 = 〚α〛.

-

(11)

Only [Mary]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) laughed. ↦

λw[{laughed(m)(w)}[max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(laughed(m))(w)]]

-

a.

requires a question of the form “Who laughed?”;

-

b.

conveys as a not-at-issue content that Mary laughed;

-

c.

conveys as an at-issue content that there is no true answer unidirectionally entailing that Mary laughed.

-

a.

The treatment of the PC of an only-sentence as a not-at-issue content is motivated by a wide array of observations, including the ones illustrated below (Beaver and Clark 2008: 216–217).

-

(12)

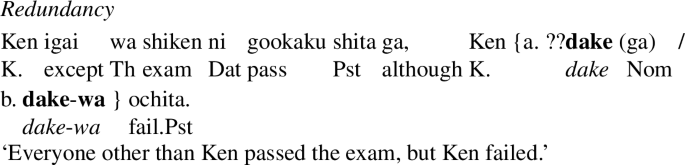

Redundancy

-

a.

Ken danced, and (indeed) only Ken did.

-

b.

??Nobody other than Ken danced, {but/and (indeed)} only Ken did.

-

a.

-

(13)

-

(14)

Emotive Evaluation

I regret that I only ordered a hamburger.

⇝ “I regret that I did not order anything other than a hamburger.”

⤳̸ “I regret that I ordered a hamburger.”

The first clause of (12a) is equivalent to the PC of the second, and the first clause of (12b) is equivalent to the NC of the second. That (12b) sounds redundant while (12a) does not suggests that an only-sentence proffers the NC but not the PC. (13) and (14) support the same conclusion, on the reasonable premise that only the at-issue content, and not the not-at-issue content, matters for the causality expressed by because and for the emotive evaluation expressed by regret.

If the PC of an only-sentence is not-at-issue, it is expected to be projective. This expectation is by and large borne out. Horn (1969: 69), for example, observes that discourse segments (15a, b) are much more naturally followed by (16a, b) than by (16c).

-

(15)

-

a.

{It’s not true that/not} only Muriel voted for Hubert.

-

b.

Did only Muriel vote for Hubert? — No, …

-

a.

-

(16)

-

a.

Lindon did too.

-

b.

Somebody else did as well, but I forgot who.

-

c.

#She didn’t.

-

a.

There are, on the other hand, reasons to believe that the PC of an only-sentence is not always projective/not-at-issue. I will come back to this matter in Sect. 4.

Regarding the cleft construction, Velleman et al. (2012) propose that it involves the semantic operator cleft whose meaning is symmetrical to that of only.

-

(17)

cleft =\(_{def}\) λp[λw[{max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w)}[p(w)]]]

-

(18)

It was [Mary]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who laughed. ↦

cleft(λw[laughed(m))(w)]) ⇒

λw[{max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(laughed(m)(w))}[laughed(m)(w)]

-

a.

requires a question of the form “Who laughed?”;

-

b.

conveys as a not-at-issue content that there is no true answer unidirectionally entailing that Mary laughed;

-

c.

conveys as an at-issue content that Mary laughed.

-

a.

Velleman et al. (2012) successfully account for the inference patterns illustrated below:

-

(19)

It was [Mary]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who laughed.

⇝ “It is not the case that Mary and John laughed.”

⇝ “Nobody other than Mary laughed.”

⇝ “Mary laughed.”

-

(20)

It was not [Mary]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who laughed. ( [(#Mary and) John]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) did.)

⇝ “It is not the case that Mary and John laughed.”

⤳̸ “Nobody other than Mary laughed.”

⤳̸ “Mary laughed.”

-

(21)

Maybe it was [Mary]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who laughed. (But it is also plausible that it was [(#Mary and) John]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who laughed.)

⇝ “It is not the case that Mary and John laughed.”

⤳̸ “Nobody other than Mary laughed.”

⤳̸ “Mary laughed.”

Besides the not-at-issue exhaustivity implication (backgrounded NC), the cleft has been said to convey an existence presupposition—the projective implication that at least one focus alternative proposition holds true. I will come back to this point in Sect. 6.1.

An important empirical question concerning the meanings of an only-sentence and a cleft is that whether their not-at-issue components—the PC for the former and the NC for the latter—are presuppositions or not. I leave this issue aside for now and will take it up in Sect. 5.

3 Dake, dake-wa, and shika

This section discusses how the meanings of the three Japanese exclusive particles, dake, dake-wa, and shika, contrast with each other in terms of at-issueness. It will be claimed, in short, that a dake-sentence proffers both its PC and NC, a shika-sentence proffers only its NC, and a dake-wa-sentence proffers only its PC (like a cleft does).

Before moving on, I would like to make a quick note on how the three particles interact with case markers, a point of some relevance to the discussion to follow. When shika and dake-wa occur on nominative or accusative arguments, the occurrence of nominative case particle ga and the accusative case particle o is suppressed. With dake, on the other hand, these case particles are optionally retained.

-

(22)

Other case particles, such as dative ni, are not suppressed. They may either precede or follow dake (ni-dake(-wa) or dake-ni(-wa)), but always precede shika (ni-shika; *shika-ni).

3.1 The (not-)at-issueness of the PC and NC

The question of how the Japanese exclusive quantifiers dake, dake-wa, and shika semantically contrast with one another has attracted a good deal of attention in Japanese linguistics (e.g., Teramura 1991; Kuno 1999a,b; Numata 2000; Hara 2007, 2014; Yoshimura 2007; Ido and Kubota 2021). I will review existing comparative discussions of (i) dake and shika (Kuno 1999a,b; among others) and (ii) dake and dake-wa (Oshima 2015), and point out some unresolved issues. I will then propose a novel analysis under which a dake-sentence proffers both PC and NC (Table 1), and argue that it successfully accounts for a fuller range of data.

3.1.1 Dake and shika

Regarding the contrast between dake and shika, Kuno (1999a,b) argues that (i) a dake-sentence conveys the PC as its “primary proposition (primary assertion)” and the NC as its “secondary proposition (secondary assertion)” and (ii) a shika-sentence, in contrast, conveys the NC as its “primary proposition” and the PC as its “secondary proposition.” This idea is anticipated by Teramura (1991: 164–169), who uses the terms omote no imi ‘meaning on the surface’ and kage no imi ‘meaning in the shade’; positions in line with these authors’ are adopted by Numata (2000) and Yoshimura (2007) too.

Kuno (1999a,b) presents utterance pairs (23) and (24) as evidence for his analysis.

-

(23)

-

(24)

The “S-(r)eba yoi” construction in (23) and the “S-te mo yoi” construction in (24) are instances what Kaufmann (2018) calls “conditional evaluative constructions.” Kuno (1999a) assigns the former the translation ‘It is sufficient if S,’ and the latter the translation ‘It is all right even if S.’

Kuno’s notions of primary and secondary propositions seem to correspond closely to the notions of at-issue (proffered) and not-at-issue (non-proffered) contents, which became increasingly accepted in the subsequent formal-semantic literature.

-

(25)

A possible rendition of Kuno’s analysis of “dake’(p)”

At-Issue Content: “p holds true.” (PC)

Not-At-Issue Content: “There is no true answer to the CQ that unidirectionally entails p.” (NC)

-

(26)

A possible rendition of Kuno’s analysis of “shika’+Neg(p)”

At-Issue Content: “There is no true answer to the CQ that unidirectionally entails p.” (NC)

Not-At-Issue Content: “p holds true.” (PC)

The “S-(r)eba yoi” and “S-te mo yoi” constructions can sensibly be regarded as expressing a qualification of the at-issue content, rather than of the not-at-issue content, of the conditional antecedent (= S). Accordingly, under the illustrated analysis, (23b)/(24a) can be understood to be pragmatically odd for the same reasons as (27b)/(28a) are.

-

(27)

-

a.

In order to make an around-the-world trip, it is sufficient if you can speak English and French.

-

b.

#In order to make an around-the-world trip, it is sufficient if you cannot speak any languages other than English and French.

-

a.

-

(28)

-

a.

#You can make an around-the-world trip even if you can speak Japanese.

-

b.

You can make an around-the-world trip even if you cannot speak any languages other than Japanese.

-

a.

The contrast between (29a) with dake and (29b) with shika can be accounted for in a similar manner.

-

(29)

The causality expressed in the second sentences of (29a, b) can reasonably be taken to target the at-issue content of the corresponding first sentence (cf. (13)). Under the accounts presented in (25)/(26), whereas (29a) implies Taro’s having winter gear was the cause of his survival, (29b) implies that Taro’s having winter gear was the cause of his companions’ deaths, which is pragmatically inconceivable.

There is, however, a major problem with the illustrated analysis: it wrongly predicts that the NC of a dake-sentence is projective. If the NC of (30) is projective, then the speaker must be committed to the truth of the hearer’s not going to buy anything other than coffee. If this were the case, it would be pointless for her to ask the subsequent question. In actuality, however, the second question can naturally be interpreted as a normal, information-seeking (rather than rhetorical) question.

-

(30)

Also, utterance (31B) does not convey that the speaker is committed to the truth of the NC, i.e., the proposition that she will not eat some bananas and some other food item.

-

(31)

One might consider that the NC of a dake-sentence is “secondary,” or “in the shade,” in a sense different from being not-at-issue. This, however, is a costly move, adding another dimension in the taxonomy of conventionally encoded meaning (cf. Ido and Kubota 2021). I maintain that dake and shika semantically contrast solely in terms of what is not-at-issue and what is not—but not in the way suggested by Teramura (1991) and Kuno (1999a,b).

3.1.2 Dake and dake-wa

Regarding the contrast between dake and dake-wa, I claimed in Oshima (2015) that their meanings are mirror images of each other, in a way similar to how Teramura (1991) and Kuno (1999a,b) take those of shika and dake to be.Footnote 3

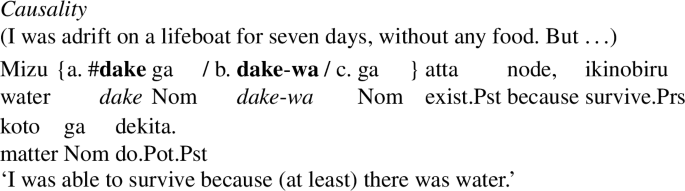

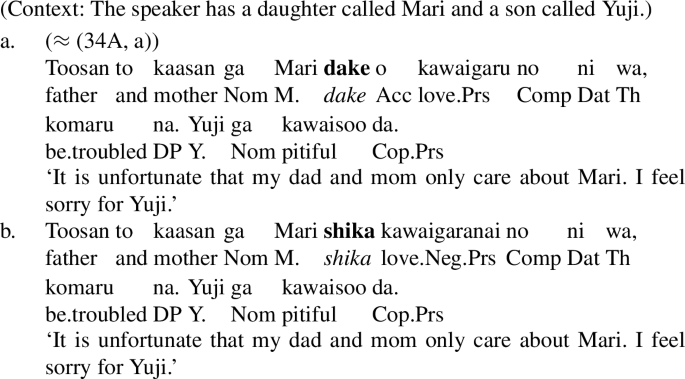

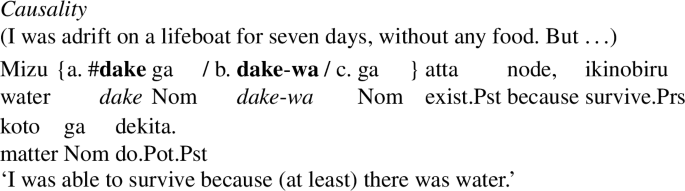

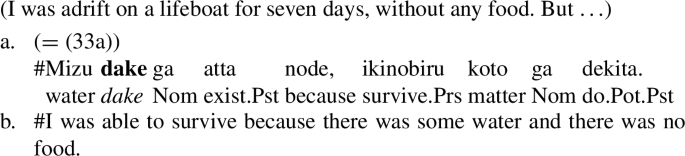

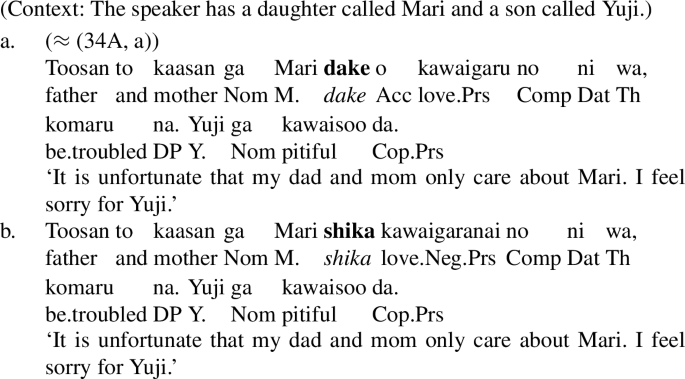

It was contended that, while a dake-sentence conveys the NC as an at-issue content and the PC as a not-at-issue one, the addition of wa to dake has the effect of reversing the two components, so that with a dake-wa-sentence the PC is at-issue and the NC is not-at-issue. This supposition is based on data like (32)–(34) (cf. (12)–(14)).Footnote 4

-

(32)

-

(33)

-

(34)

The first clause of (32) is equivalent to the NC of the second. The relative unnaturalness of (32a) can be attributed to the same content being proffered twice, and the naturalness of (32b) suggests that this redundancy is avoided, with the NC being not-at-issue. (33a) is odd because it implies that the lack of things other than water was the cause of the speaker’s survival, while (33b) is sensible because it, like (33c), implies that the existence of water was the cause of the speaker’s survival. (34A, b) is odd because it implies that A is unhappy that his parents care about his daughter (= the at-issue content of the complement clause), and (34B, a) is odd because it implies that B thinks it is a good thing that her parents-in-law do not care about her son (= the at-issue content of the complement clause).

This analysis, however, leaves unexplained why some only-sentences, such as (35a) (repeated from (5b)) and (36a), cannot be naturally translated with dake, as discussed by Yoshimura (2007: 109–111).

-

(35)

-

(36)

Note that this contrast is given a straightforward account under the Teramura-Kuno analysis sketched out in (25)/(26).

3.2 Reconciliation of the two accounts

I maintain that both the Teramura-Kuno account of dake and shika and Oshima’s (2015) proposal as to the contrast of dake and dake-wa are partly correct and partly wrong. The former is correct that the PC of a shika-sentence is backgrounded while that of a dake-sentence is not. The latter is correct that the NC of a dake-wa-sentence is backgrounded while that of a dake-sentence is not. They both fail, however, to capture the symmetrical (dual-foreground) nature of the meaning of a dake-sentence.

Data like (23)/(24) and (29) merely show that the PC of a dake-sentence is part of the at-issue content, and not that it is the sole at-issue content. Likewise, data like (32)–(34) merely show that the NC of a dake-sentence is part of the at-issue content, and not that it is the sole at-issue content. I propose that, with a dake-sentence, both PC and NC are parts of the at-issue content.

The way the three Japanese exclusive quantifiers contrast with each other in terms of (not-)at-issueness can be summarized as follows. (A more refined version of this will be given in Sect. 5.3.)

-

(37)

“dake’(p)”

At-Issue Content (i): “p holds true.” (PC)

At-Issue Content (ii): “There is no true answer to the CQ that unidirectionally entails p.” (NC)

-

(38)

“shika’+Neg(p)”

At-Issue Content: “There is no true answer to the CQ that unidirectionally entails p.” (NC)

Not-At-Issue Content: “p holds true.” (PC)

-

(39)

“dake-wa’(p)”

At-Issue Content: “p holds true.” (PC)

Not-At-Issue Content: “There is no true answer to the CQ that unidirectionally entails p.” (NC)

This analysis provides a straightforward account of the full range of empirical observations made so far, which I will revisit below in the following order.

-

(40)

-

a.

The projection patterns (relevant data: (6), (30), (31))

An (embedded) dake-sentence does not necessarily convey that the speaker is committed to the truth of either the PC or the NC. A {dake-wa-sentence/shika-sentence} implies the speaker’s commitment to the truth of the {PC/NC}.

-

b.

Redundancy (relevant data: (32), (35))

A dake-sentence sounds awkward when the PC is common ground, as well as when the NC is common ground.

-

c.

Causality (relevant data: (29), (33), (36))

In an explicans sentence (e.g., S2 in “S1 because S2”), {dake-wa/shika} is chosen when it is the {PC/NC} that “matters” (i.e. counts as the reason); dake is chosen when both PC and NC matter.

-

d.

Emotive evaluation (relevant data: (34))

In the complement clause of an attitude predicate with emotive evaluation (e.g., S in “I regret that S”), {dake-wa/shika} is chosen when it is the {PC/NC} that “matters” (i.e. serves as the target of the evaluation); dake is chosen when both PC and NC matter.

-

e.

Conditional evaluative constructions (relevant data: (23), (24))

In the conditional antecedent (S) of the “S-(r)eba yoi” construction, dake but not shika can be chosen when the PC “matters” (i.e. is claimed to guarantee the satisfactoriness of the situation). In the conditional antecedent (S) of the “S-te mo yoi” construction, shika but not dake can be chosen when the NC “matters” (i.e. is claimed to be compatible with the satisfactoriness of the situation).

-

a.

3.2.1 The projection patterns

In the context of (41) (repeated from (6)) only the version with dake is appropriate. The conditional antecedent of (41a, ii) with dake-wa conveys as a projective content that Toru and Masaki will not win, and that of (41b) with shika conveys as a projective content that Ken will win. (41a, ii) and (41b) are pragmatically deviant since the speaker here cannot be expected to be committed to either of these propositions.

-

(41)

The current analysis correctly predicts that neither the PC nor NC of the embedded dake-sentence in (41i, a) projects through the conditional antecedent. It also conforms to the inference patterns seen in (30) and (31).

3.2.2 Redundancy due to the dual-foregroundedness of dake

The oddness of (42a) (= (35b)) can be attributed to the redundancy incurred by its proffering what already is common ground. In the context here, both interlocutors are aware that egg sandwiches were available, and this makes the proffered PC of the dake-sentence redundant.

-

(42)

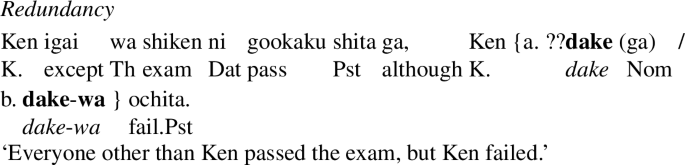

In (43) (= (32a)), in contrast, it is the NC of a dake-sentence that is redundantly proffered, incurring oddness.

-

(43)

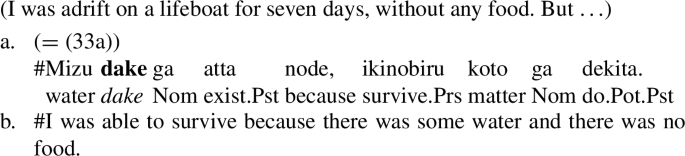

3.2.3 Misaligned causality

The oddness of (44a) can be likened to the oddness of English utterance (44b).

-

(44)

(44a) and (44b) both convey that if it were not the case that (i) there was some water and (ii) there was no food (e.g., if it were the case that there was both food and water), the speaker would not have survived, contradicting our common-sensical reasoning.

Likewise, the oddness of (45a) can be likened to that of (45c).

-

(45)

Note that, with (45a), it is the PC, rather than the NC, that interferes with the expressed causality. The oddness of (45a), as well as that of (45c), is mitigated if it is contextually assumed that the speaker ate something at least as filling as bananas—for example, if it is known that the speaker chose one of the three options: (i) to eat two bananas (for $10), (ii) to eat one cheeseburger (for $20), (iii) to eat both (for $30)—because this premise validates the inference that if it were not the case that the speaker ate some bananas and nothing else, then he would be less hungry.

The oddness of (46a), where the second sentence is understood to explain the cause of the content of the first clause, can be likened to the oddness of English utterance (46b).

-

(46)

Here again, it is the PC of the dake that interfers with the (implicitly understood) causality.

In (47), either the version with dake or dake-wa is acceptable (cf. (29)).

-

(47)

The acceptability of (47a) is intriguing, as it is quite weird to say that Taro’s having winter gear caused Taro’s survival and his companions’ deaths. I suggest that when a dake-clause is used, both of its two at-issue contents (PC and NC) become available as potential antecedents of anaphoric reference, and in (47a), the second sentence anaphorically refers to the PC of the first sentences, and thereby means that the reason why Taro survived was that he had winter gear.

Corroborating this supposition, (48a) illustrates that the NC of a dake-sentence too can be anaphorically referred by an item in a subsequent sentence.Footnote 5

-

(48)

3.2.4 Emotive evaluation targeting the wrong semantic component

In the context of (34A), it is natural to use shika instead of dake.

-

(49)

Under the current analysis, (49b) with shika expresses the speaker’s negative evaluation on the fact that his parents do not care about his son, while (49a) with dake expresses his negative evaluation on the fact that his parents care about his daughter and do not care about his son. That your parents love some of your children and not the others could be as aggravating as, or more aggravating than, that they love none, and the two situations could be aggravating in distinct ways, too (e.g., the former more likely incurs jealousy or a feeling of unfairness). As such, the speaker’s parents caring about his daughter has a potential to weigh on his negative evaluation of the situation, making the choice of dake sensible.

In a similar vein, either (50a) with dake or (50b) with shika can be natural, depending on the background contexts.

-

(50)

In the situation described in (51a), where both NC and PC contribute to the positive evaluation (it is a good thing that Mari passed, and it is also a good thing that Emi and Yuki failed), either (50a) or (50b) is natural. In Situation (51a), where only the NC contributes to the positive evaluation (it is a good thing that Emi and Yuki failed, but it is neither a good thing nor a bad thing that Mari passed), (50b) is more natural than (50a).

-

(51)

-

a.

The speaker likes Mari, and wanted her to prove that she was better than Emi and Yuki.

((50a): √, (50b): √)

-

b.

The speaker dislikes Emi and Yuki, and hoped that they would fail the exam. He is indifferent about Mari.

((50a): ??, (50b): √)

-

a.

In (52), in contrast, only the version with shika is natural, because it is implausible that the speaker’s having an option to eat bananas (= the PC) contributes to the expressed negative evaluation.

-

(52)

3.2.5 The “S-(r)eba yoi” and “S-te mo yoi” constructions

The current analysis can also account for the availability of dake in (23a), repeated as (53).

-

(53)

(54) is a paraphrase of (53a) reflecting the dual-foregroundedness of a dake-clause. This is a reasonable statement, although the conjunct and no other language makes it sound somewhat awkward. Hence, (53a) need not be taken to favor the account of dake à la Kuno (1999a,b), where only the PC is foregrounded, over the proposed account.

-

(54)

In order to make an around-the-world trip, it is sufficient if you speak English, French, and no other language.

The degraded acceptability of (24a), repeated as (55), is somewhat intriguing, as its paraphrase given in (56) seems more or less as reasonable (and awkward) as (54).

-

(55)

-

(56)

In order to make an around-the-world trip, it is all right even if you can speak Japanese and no other language.

Note, however, that the oddness of (55) is relatively mild, as reflected by Kuno’s (1999a, 1999b) marking it with “??/#” rather than “#” (cf. (23b)). Furthermore, pace Kuno (1999a), ‘It is all right even if S’ appears not to be an apt translation of the “S-te mo yoi” construction. To corroborate this point, utterance (57) with the “S-te mo yoi” construction, by a doctor to a patient, does not imply that drinking water is undesirable and is not amenable to translation with ‘It is all right even if S.’

-

(57)

With the alternative, and presumably more faithful, translation ‘It does not matter whether or not S’ for “S-te mo yoi,” (55) and its shika-variant (58) (repeated from (24b)) respectively amount to saying (59a), which sounds quite odd, and (59b), which sounds, prolixity aside, reasonable.

-

(58)

-

(59)

-

a.

??For the purpose of making an around-the-world trip, it does not matter whether or not you can speak Japanese and no other language.

-

b.

For the purpose of making an around-the-world trip, it does not matter whether or not you cannot speak any {language other than Japanese/foreign language}.

-

a.

The oddity of (55) can plausibly be likened to that of (59a).

3.3 The PC-foregrounded interpretation of dake

Dake (without wa) occurring on a quantificational adverbial (sometimes called “floating quantifier”) may induce the PC-foregrounded, or dake-wa-like, interpretation, instead of the expected dual-foregrounded (symmetrical) interpretation. In other words, an analysis along the lines of Kuno (1999a,b) is appropriate for some instances of dake.

While the instance of dake in (60Ba) receives the expected dual-foregrounded interpretation, the one in (61a) receives the PC-foregrounded interpretation (ni-joo and mittsu are both quantificational adverbs).

-

(60)

-

(61)

In (60a), both PC and NC of the explicans clause are relevant to the expressed causality. In (61), on the other hand, it is only the PC of the explicans clause that is relevant to the expressed causality; if there were four or more sandwiches left at the shop, the content of the explicandum clause would still hold true.

One may say that wa within dake-wa may be “left out” when the host constituent is a quantificational adverbial. When dake occurs on an argument nominal, the PC-foregrounded interpretation is hardly available. This can be seen with examples (32)–(34) above, as well as (62) where a quantificational adverbial (ittoo) and a subject (chairo no koushi) exhibit a contrasting pattern (recall that dake-wa obligatorily suppresses the nominative marker ga).

-

(62)

(62b, ii) is odd, suggesting that some other calf’s dying (in addition to or instead of the brown calf’s dying) was desirable.

It appears, however, that the PC-foregrounded interpretation of a dake occurring on an argument nominal becomes comparatively more tolerable when it does not co-occur with a case particle such as nominative ga and accusative o.

-

(63)

-

(64)

What factors (argumenthood, co-occurrence and relative order with a case particle, and others) weigh to what extent on the (un)availability of the PC-foregrounded interpretation of dake, and why these factors have such effects, are issues that call for further inquiries.

4 Only revisited

As noted in Sect. 2, it has been commonplace to suppose that an only-sentence conveys its PC as a not-at-issue/projective content. There are reasons, on the other hand, to believe that this is not always the case. To illustrate, the utterer of (65) is not taken to be committed to the truth of Seki’s having taught extremely smart people, and the utterer of (66), repeated from (5a), is not taken to be committed to the truth of Ken’s winning his last match.

-

(65)

I asked Dr. Seki to teach me some math, which turned out to be a bad idea. We spent two hours and I did not understand a thing. I doubt he has any experiences in teaching. Or maybe he has only taught extremely smart people.

-

(66)

(Context: Ken, Toru, and Masaki are competing in a round-robin chess tournament with 10 participants. The three of them are tied in the first place, each with seven wins and two losses. They will have their last match today, each playing against a different opponent.)

If only Ken wins today, he will be the champion. However, the past results suggest that he has only about a 40% chance of winning against his opponent.

Such observations appear to lend support to the so-called symmetrical (conjunctive) analysis of only, variants of which are adopted or advocated by such authors as Taglicht (1984); Atlas (1991, 1993); and Krifka (1992a).

One way to make sense of the apparently conflicting sets of data—and to reconcile the asymmetrical and symmetrical approaches to the semantics of only—is to suppose that only is lexically ambiguous and a sentence with logical form “only’(p)” allows two readings. One is the PC-backgrounded reading, which can also be characterized as the “shika-like” reading. The other is the symmetrical reading, which can also be characterized as the “dake-like” reading.

-

(67)

“only’(p)” on its PC-backgrounded reading

At-Issue Content: “There is no true answer to the CQ that unidirectionally entails p.” (NC)

Not-At-Issue Content: “p holds true.” (PC)

-

(68)

“only’(p)” on its symmetrical reading

At-Issue Content (i): “p holds true.” (PC)

At-Issue Content (ii): “There is no true answer to the CQ that unidirectionally entails p.” (NC)

The two readings are, however, not on a par with each other. The symmetrical reading is marked, and is available only when the context makes it implausible that the speaker is committed to the truth of the PC, as in (65)/(66).

In what follows, \(\textit{only}_{\textrm{A}}\) refers to only on its typical asymmetrical (PC-backgrounded) interpretation, and \(\textit{only}_{\textrm{S}}\) refers to only on its atypical symmetrical interpretation.

5 Presuppositional vs. non-presuppositional not-at-issue contents

I have so far examined how the exclusive quantifiers under discussion contrast with each other in terms of at-issue/not-at-issue configurations. One issue I have been putting aside is the (non-)presuppositionality of the not-at-issue component (if any) of a sentence with an exclusive quantifier.

To clarify, in the current work the notion of “not-at-issue (or non-proffered) content” is understood in a relatively broad way, as an equivalent of “projective content” (Tonhauser et al. 2013) and as a category subsuming “presupposition” as well as “expressive content” (contributed by interjections, slurs, etc.)

-

(69)

Presuppositional not-at-issue contents, or simply presuppositions, will be understood as (i) those propositional meanings that are required to have been part of the interlocutors’ common ground prior to the utterance, plus (ii) those semantic components of non-clausal constituents (involving a so-called presupposition trigger) which potentially contribute to such propositional meanings. They correspond to “projective contents that are subject to the Strong Contextual Felicity constraint” in the taxonomy in Tonhauser et al. (2013).Footnote 6

The presuppositionality of a not-at-issue content can be represented by making reference to the context set (CS), the intersection of all propositions acknowledged by the interlocutors as holding true. (70) and (71) exemplify how a non-presuppositional not-at-issue content (e.g. the content of a non-restrictive relative clause) and a presuppositional content (e.g. the existence implication induced by additive too) may be represented.

-

(70)

Amy, who is a linguist, laughed. ↦

λw[{linguist(a)(w)}[laughed(a)(w)]]]

-

a.

conveys as a non-presuppositional not-at-issue content that Amy is a linguist;

-

b.

conveys as an at-issue content that Amy laughed.

-

a.

-

Amy

\(_{\textrm{F}}\) laughed, too. ↦

λw[{CS ⊆ λw’[∃p∈CQ[p≁λw”[laughed(a)(w”)] & p(w’)]]}

[laughed(a)(w)]]

-

a.

requires a question of the form “Who laughed?”;

-

b.

conveys as a presuppositional not-at-issue content that some answer that is logically independent from the proposition that Amy laughed holds true;

-

c.

conveys as an at-issue content that Amy laughed.

-

a.

-

(72)

p≁q \(=_{def}\) ¬[p⊆q] & ¬[q⊆p]

5.1 The non-presuppositionality of the PC of an only-sentence and the NC of a cleft

In Beaver and Clark (2008), Coppock and Beaver (2011), and Velleman et al. (2012), the PC of an \(\textit{only}_{(\textrm{A})}\)-sentence and the NC of a cleft are referred to as “presuppositions.” This, however, does not conform to the terminology illustrated above.

In conversation (73), the use of only by interlocutor B is felicitous despite it not being common ground that Amy and Bruce showed up, suggesting that the PC of an only-sentence is non-presuppositional, making a contrast with the existence implication induced by additive too (see also Tonhauser et al. 2013: 103).

-

(73)

It can be shown that the not-at-issue content (NC) of a cleft is not presuppositional, either. In (74B2), the use of the it-cleft is felicitous despite it being contextually plausible that three people were hired by Professor Xia. Uttering (74B2), interlocutor B conveys that it is not the case that Amy, Bruce, and someone else (say Chris) were hired without taking this piece of information to be part of the common ground.

-

(74)

The same point is illustrated with Japanese example (75), where the use of the no-cleft by interlocutor B is felicitous despite it being contextually plausible that Yamada came to talk to her on five or six days including the 5th, 9th, 15th, and 23rd.

-

(75)

5.2 The non-presuppositionality of the PC of a shika(/dake)-sentence and the presuppositionality of the NC of a dake-wa-sentence

A shika-sentence, like an only\(_{(\textrm{A})}\)-sentence, conveys its NC as a non-presuppositional, rather than presuppositional, not-at-issue content. To illustrate, (\(\text{76B}_{a}\)) as well as (\(\text{76B}_{b}\)) is a natural response to (76A), not implying that A has known or expected beforehand that B ate some bananas. Note that the naturalness of (\(\text{76B}_{b}\)) is not surprising given that its NC is at-issue (and thus necessarily non-presuppositional).

-

(76)

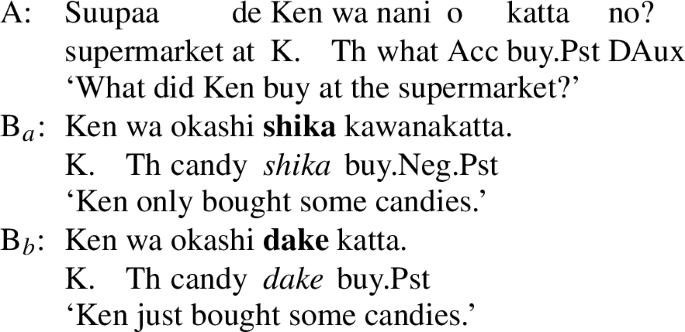

Likewise, (\(\text{77B}_{a}\)) as well as (\(\text{77B}_{b}\)) is a natural response to (77A), not implying that A has known or expected beforehand that Ken bought candies.

-

(77)

The not-at-issue content (NC) of a dake-wa sentence, on the other hand, is presuppositional. This is evidenced by the observation that (78)/(79) do not make natural responses to (76A)/(77A).

-

(78)

-

(79)

The use of dake-wa becomes natural when the interlocutors’ shared knowledge makes it plausible, if not guarantees, that the NC holds true.

-

(80)

-

(81)

As such, the semantic symmetry between dake-wa and shika is not complete.

5.3 Putting the pieces together

The semantic analyses of only (on its asymmetrical and symmetrical readings) and the three Japanese exclusive particles, which reflect the presuppositional status of the NC induced by dake-wa, are shown below. Recall that \(\textit{only}_{\textrm{S}}\) and \(\textit{only}_{\textrm{A}}\) are semantically equivalent to shika+Neg and dake, respectively.

-

(82)

-

a.

only\(_{\textrm{S}}\) ↦ λp[λw[{p(w)}[max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w)]]]

-

b.

only\(_{\textrm{A}}\) ↦ λp[λw[p(w) & max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w)]]]

-

a.

-

(83)

dake ↦ λp[λw[p(w) & max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w)]]]

-

(84)

shika+Neg ↦ λp[λw[{p(w)}[max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w)]]]

-

(85)

dake-wa ↦ λp[λw[{CS ⊆ λw’[max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w’)]}[p(w)]]]

The formulation of the semantics of the cleft, slightly revised from the one given earlier in (17), follows shortly.

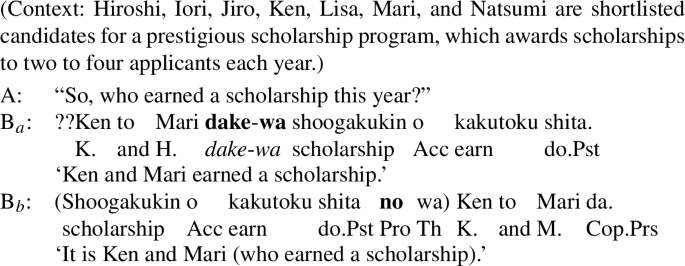

6 Comparison of dake-wa and the cleft

The proposed meaning of a dake-wa sentence is quite similar to the meaning of the cleft construction posited by Velleman et al. (2012). They both convey their PC as an at-issue content and their NC as a not-at-issue content. Yet, they differ considerably in terms of discourse-configurational distributions. This section discusses how the relatively small semantic difference between dake-wa sentences and clefts cause some of the difference in their distributions. It will be argued, contra Velleman et al., that the cleft construction conventionally encodes an existence presupposition.

6.1 Contexts that favor dake-wa but disfavor the cleft

(86a) with dake-wa is felicitous, while (86b, c) with the no/it-cleft is not.

-

(86)

Note that at the point dake-wa/the cleft is used, the information that nobody other than Ken failed the exam is part of the common ground, so that the NC is known to hold true.Footnote 7 The infelicity of (86b, c) is to be attributed to the failure of the existence presupposition triggered by the cleft.

It has long been observed that, besides exclusivity, the cleft conveys an existence presupposition—the projective implication that at least one focus alternative proposition holds true (e.g. Horn 1981; Rooth 1999; Abusch 2010; Büring and Križ 2013).Footnote 8

-

(87)

Maybe it was [Amy]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who laughed.

⇝ “Somebody laughed.”

Velleman et al. (2012) suggest that the putative existence presupposition of a cleft is posited as part of the coded meaning. They argue that the oddity of (88) arises from a pragmatic inference, based on the reasoning quoted below.

-

(88)

This account, however, cannot be applied to a case like (89), where the speaker is not committed to the CQ’s having no true (positive) answer, and thus is not in a position to reject it.

-

(89)

#I don’t know if anyone laughed. Maybe it was [Alice]\(_{\textrm{F}}\) who laughed, but it is also plausible that nobody laughed.

To make an account along these lines work, we need the stronger assumption that it is uncooperative to make reference to a CQ (e.g. with a cleft) if one is not certain that it has at least one true answer.

The depicted pragmatic-inference-based account, however, leaves unexplained why a projective existence implication does not arise from the use of dake-wa, as illustrated in (90), or dake/only\(_{\textrm{S}}\) (see e.g. (65)).

-

(90)

Dake(-wa) and only\(_{\textrm{(S)}}\) make reference to the CQ like the cleft does, and thus, under the reasoning of Velleman et al., should signal that the speaker believes that there is at least one true answer to the CQ—which evidently is not the case in (65)/(90).

It thus seems reasonable to accept the received wisdom that the cleft encodes the existence presupposition. (91) is the version of the cleft operator adopted in this work, which incorporates this additional not-at-issue content.

-

(91)

cleft∃ \(=_{def}\)

λw[λp[{CS ⊆ λw’[∃q∈CQ[q(w’)]] & max\(_{\textrm{info}}\)(p)(w)}[p(w)]]

6.2 Contexts that favor the cleft but disfavor dake-wa

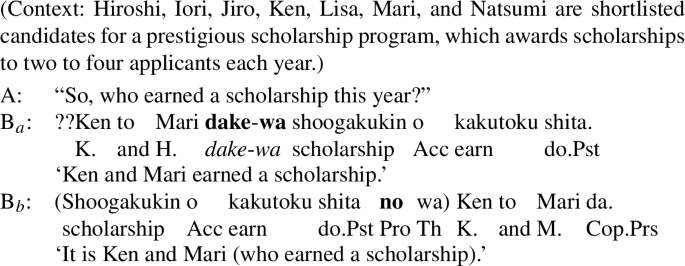

In (92), the response with a cleft is felicitous, while the one with dake-wa is not.

-

(92)

The infelicity of (\(\text{92B}_{a}\)) can be straightforwardly attributed to the presupposition failure—B cannot sensibly take it to be common ground that it is not the case that Ken, Mari, and somebody else earned a scholarship.

Next consider the discourse in (93); here too, the choice of dake-wa is considerably less natural than that of the cleft.

-

(93)

Note that here it is common ground that it is not the case that Ken ate some bananas and some other food item.

I suggest that the relative unnaturalness of (\(\text{93B}_{a}\)) arises from a discourse principle along the lines of Maximize Presupposition (Heim 1991). The principle of Maximize Presupposition comes in a number of different formulations, but in essence it requires that, given a set of comparable forms sharing the same proffered content but differing in what they presuppose (e.g., {all, both}), the speaker choose the one with the strongest presupposition compatible with the discourse context. This principle has been applied to the broader category of not-at-issue content (e.g. McCready 2019: 53)—making it more appropriate, under the current terminology, to call it “Maximize Not-At-Issue Content,” rather than Maximize Presupposition.

Now, how do dake-wa and the cleft compare with each other in terms of the strength of their not-at-issue content? The not-at-issue content of “cleft∃(p),” i.e. (94), does not unidirectionally entail that of “dake-wa’(p),” i.e. (95), and vice versa.

-

(94)

(i) There is no true alternative of p that unidirectionally entails it and (ii) it is common ground that some alternative of p holds true.

-

(95)

It is common ground that there is no true alternative of p that unidirectionally entails it.

On the other hand, (94) does convey more information than (95) when the factor of presuppositionality is put aside. It seems not unreasonable to hypothesize that this makes the cleft a choice favored over dake-wa when the not-at-issue content of either holds true. Under this account, the unnaturalness of (\(\text{93B}_{a}\)) can be likened to that of (96b).

-

(96)

Ken closed {a. both/b. #all} of his eyes.

(96b) sounds odd, implicating that the speaker does not acknowledge that Ken does not have more than two eyes; (\(\text{93B}_{a}\)) sounds odd, implicating that the speaker does not acknowledge that Ken ate something (despite this information having just been presented to her).

7 The role of wa in dake-wa

The particle wa, which constitutes part of dake-wa, is said to have two uses, called thematic and contrastive. The former indicates information-structural topichood or groundhood (non-focushood) of the marked constituent (Oshima 2021); the latter is a focus-alternative quantifier, and conveys that some alternative proposition is possibly false (Oshima 2020). It is interesting to ask how the meaning of dake-wa might be compositionally derived with those of dake and wa.

Oshima (2020) assigns a meaning along the lines of (97) to contrastive wa (wa\(_{\textrm{c}}\) for short).Footnote 9

-

(97)

wa\(_{\textrm{c}}\) ↦ λp[λw[{Bel(S) ⊈ λw’[∀q∈CQ[q≁p→ q(w’)]}[(p)(w)]]]

-

(98)

The posited not-at-issue content is strictly weaker than the exclusivity implication of dake(-wa), shika, etc. It is plausible that the not-at-issue content induced by \(\textit{wa}_{\textrm{c}}\) is inherited to a dake-wa sentence, but ends up being trivial and indiscernible. Sentence (99), for example, might convey three pieces of information, (99b–d), at the level of logical representation, with (99c) being redundant given (99b).

-

(99)

The question of how the attachment of \(\textit{wa}_{\textrm{c}}\) affects the meaning of dake thus seems reducible to the question of how it triggers the “presuppositionalization” of the NC induced by dake. I will not pursue this issue further here. It is worth noting, however, that dake-wa is presumably an instance of the cross-linguistically observed, and not well-understood, phenomenon whereby more than one focus-alternative quantifier is associated with a single focus item (Krifka 1992b; Guerzoni 2003; Nakanishi 2006; De Cesare and Garassino 2015). Inquiry into dake-wa has a potential to contribute to a better understanding of other instances of “focus-alternative-quantifier clusters,” and vice versa.

8 Conclusion

A comparative analysis of (i) the English exclusive quantifier only, (ii) the three Japanese exclusive quantifiers, dake, dake-wa, and shika, and (iii) the cleft construction (the English it-cleft and the Japanese no-cleft), was put forth. An only-sentence typically, and a shika-sentence invariably, convey the PC as a non-presuppositional, not-at-issue content. A dake-sentence typically conveys both PC and NC as at-issue contents. A dake-wa-sentence conveys the NC as a presuppositional not-at-issue content, while the cleft conveys the NC as a non-presuppositional not-at-issue content and additionally conveys an existence presupposition. Only sometimes receives the dake-like symmetrical interpretation. Dake may receive the dake-wa-like PC-foregrounded interpretation in limited configurations. Table 2 summarizes the correspondence between these exclusive quantifiers in terms of (not-)at-issueness and presuppositionality (“√” indicates the unmarked/default interpretation).

The current work contributes to the general-linguistic taxonomy of focus-alternative quantifiers, providing a systematic semantic account of representative exclusive quantifiers in two well-studied languages, English and Japanese. An exclusive quantifier may convey the PC, the NC, or neither as a not-at-issue (backgrounded) content. A backgrounded NC, and in theory a backgrounded PC too, may be either non-presuppositional or presuppositional. Additionally, some exclusive quantifiers allow the so-called rank-based interpretation (as in “Amy is only a sergeant (and not a lieutenant, etc.)”), while some others do not (footnote 2). It is yet to be inquired which of the possible combinations of these features are attested across languages, how commonly and in what ways—monomorphemically, as in only, polymorphemically, as in dake-wa, or constructionally, as in clefts.

Notes

The abbreviations in glosses are: Acc = accusative, Attr = attributive, Aux = auxiliary, Ben = benefactive auxiliary, Cl = classifier, Cop = copula, Dat = dative, DAux = discourse auxiliary, DP = discourse particle, Evid = evidential auxiliary, Gen = genitive, Ger = gerund, Inf = infinitive, Intj = interjection, Neg = negation, NegAux = negative auxiliary, Nom = nominative, Npfv = nonperfective auxiliary, Pl = plural, Plt = polite, PltAux = politeness auxiliary, Pot = potential, Pro = pronoun, Prov = provisional, Prs = present, Pst = past, Th = thematic wa (topic/ground-marker).

(8) is considerably simplified from the analysis put forth by the original authors, which is designed to be extendable to the so-called rank-based, or importance-based, interpretation of only illustrated in (i).

-

(i)

This work focuses on the more typical, entailment-based reading of only, which is amenable to the analysis shown in (8). It bears noting that all other exclusive quantifiers discussed in the current work—the cleft and Japanese dake, dake-wa, and shika—invariably convey entailment-based, rather than rank-based, exclusivity, making only an oddball in this respect.

-

(i)

Hara (2014: 525; see also Hara 2007) suggests that the meaning of dake-wa (but not that of dake) involves exhaustification of potential speech acts, so that (i-a) has the same propositional content as (i-b) but conveys that “the speaker is willing to make assertions only about John and the alternative speech acts about other individuals are canceled.”

-

(i)

Her analysis leads to the prediction that the utterer of (i-a), like the one of (ii), is not necessarily to be regarded as being dishonest (rather than just secretive) when she indeed knew that some people other than John came.

-

(ii)

This is problematic, as (i-a), unlike (ii), robustly supports the inference that nobody other than John came.

-

(i)

A dake-wa-sentence is often amenable to translation with at least on its concessive reading (exemplified in “I did not win the gold medal, but at least I won the silver medal”; Nakanishi and Rullmann 2009), as in (33)/(34B). Concessive at least presupposes that preferable alternatives of the prejacent-proposition do not hold, and this comes close to what I will argue to be the meaning of dake-wa (which however does not make reference to a preference-based scale).

It seems also possible for the conjunction of the PC and the NC of a dake-sentence to serve as the target of anaphoric reference. In (i), the implicit subject of the second sentence presumably makes anaphoric reference to the conjunction of the PC and NC of the first sentence.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Tonhauser et al. (2013) put forth a four-way classification of projective (not-at-issue) contents, where projective contents contrast in two dimensions: (i) whether or not they are subject to the Strong Contextual Felicity constraint (whether they are presuppositional or non-presuppositional), and (ii) whether or not they exhibit the Obligatory Local Effect or not—i.e., whether they make reference to the local, rather than global, context when embedded under an attitude predicate (see also Oshima 2016). Tonhauser et al. (2013) take the projective implication induced by only\(_{\textrm{(A)}}\) (the PC of an only\(_{\textrm{(A)}}\)-sentence) to be associated with the Obligatory Local Effect; I agree, and also assume that the same goes with the PC of a shika-sentence, the NC of a dake-wa sentence, and the NC of a cleft.

A case could be made that the no-cleft in (86b) is deemed inappropriate because the alternative strategy to use dake-wa, which marks the presuppositionalty of the NC, is preferable. This account, however, cannot be extended to the inappropriateness of the it-cleft in (86b), which does not have a competing strategy corresponding to dake-wa.

It has been noted that sometimes a cleft can be felicitously used despite its existence implication not being part of the common ground. For example, in oft-cited (i), it is evident that the author does not take it to be part of the reader’s knowledge that the incident described in the that-clause happened (at some time).

-

(i)

It appears, on the other hand, that such instances of the cleft are confined in certain types of narratives, and are not permissible in, for example, daily conversations. I thus adopt the view that the existence commitment of a cleft is as a rule presuppositional, but this rule may be violated sometimes to incur a special stylistic effect.

-

(i)

Hara (2007) puts forth a similar analysis of contrastive wa, along the lines of (i):

-

(i)

wa\(_{\textrm{c}}\) ↦ λp[λw[{Bel(S) ⊈ λw’[∀q∈CQ[q⊂p → q(w’)]}(p)(w)]]]

It makes problematic predictions on the semantic contribution of contrastive wa embedded in an entailment-canceling environment. It wrongly predicts, for example, that (ii) is compatible with a situation where it is common ground that everyone other than Ken passed the exam (here, the speaker is naturally taken to find it possibly false that everyone including Ken passed the exam, so that the putative not-at-issue content expected from (i) is satisfied).

-

(ii)

-

(i)

References

Abusch, Dorit. 2010. Presupposition triggering from alternatives. Journal of Semantics 27: 37–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffp009.

Atlas, Jay David. 1991. Topic/comment, presupposition, logical form and focus stress implicatures: The case of focal particles only and also. Journal of Semantics 8: 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/8.1-2.127.

Atlas, Jay David. 1993. The importance of being ‘only’: Testing the neo-Gricean versus neoentailment paradigms. Journal of Semantics 10: 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/10.4.301.

Beaver, David I., and Brady Z. Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bonomi, Andrea, and Paolo Casalegno. 1993. ‘Only’: Association with focus in event semantics. Natural Language Semantics 2: 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01255430.

Büring, Daniel. 2003. On D-trees, beans, and B-accents. Linguistics and Philosophy 26(5): 511–545.

Büring, Daniel, and Manuel Križ. 2013. It’s that, and that’s it! Exhaustivity and homogeneity presuppositions in clefts (and definites). Semantics and Pragmatics 6(Art. 6): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.6.

Cho, Sungdai, John Whitman, and Yuko Yanagida. 2008. Clefts in Japanese and Korean. In Proceedings of the 44th annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, Vol. 1, 61–77. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

De Cesare, Anna-Maria, and Davide Garassino. 2015. On the status of exhaustiveness in cleft sentences: An empirical and cross-linguistic study of English also-/only-clefts and Italian anche-/solo-clefts. Folia Linguistica 49: 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1515/flin-2015-0001.

Coppock, Elizabeth, and David Beaver. 2011. Sole sisters. In Proceedings of SALT 21, 197–217.

Guerzoni, Elena. 2003. Why even ask?: On the pragmatics of questions and the semantics of answers. PhD diss, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hara, Yurie. 2007. Dake-wa: Exhaustifying assertions. In New frontiers in artificial intelligence: Joint JSAI 2006 workshop post-proceedings, eds. Takashi Washio, Ken Satoh, Hideaki Terada, and Akihiro Inokuchi, 219–231. Berlin: Springer.

Hara, Yurie. 2014. Topics are conditionals: A case study from exhaustification over questions. In Proceedings of the 28th Pacific Asia conference on language, information and computation, eds. Wirote Aroonmanakun, Prachya Boonkwan, and Thepchai Supnithi, 522–531. Chulalongkorn University.

Heim, Irene. 1991. Artikel und definitheit. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, eds. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 487–535. Berlin: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110126969.7.487.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2012. Syntactic metamorphosis: Cleft, sluicing, and in-situ focus in Japanese. Syntax 15(2): 142–180.

Horn, Lawrence. 1969. A presuppositional analysis of only and even. In Papers from the 5th regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, Vol. 5, 98–107. Chicago Linguistic Society.

Horn, Lawrence. 1981. Exhaustiveness and the semantics of clefts. In Proceedings of the 11th annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, Vol. 11, 125–142. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/nels/vol11/iss1/10.

Ido, Misato, and Yusuke Kubota. 2021. The hidden side of exclusive focus particles: An analysis of dake and sika in Japanese. Gengo Kenkyū 160: 183–213. https://doi.org/10.11435/gengo.160.0_183.

Karttunen, Lauri, and Stanley Peters. 1979. Conventional implicature. In Presupposition, eds. Choon-Kyu Oh and David A. Dinneen. Vol. 11 of Syntax and semantics, 1–56. New York: Academic Press.

Kaufmann, Magdalena. 2018. What ‘may’ and ‘must’ may be in Japanese. In Japanese/Korean linguistics, eds. Kenshi Funakoshi, Shigeto Kawahara, and Christopher D. Tancredi, Vol. 24, 103–126. CSLI Publications.

Krifka, Manfred. 1992a. A framework for focus-sensitive quantification. In Proceedings of semantics and linguistic theory 2, eds. Chris Barker and David Dowty, 215–236. Dept of Linguistics, Ohio State University. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v2i0.3024.

Krifka, Manfred. 1992b. A compositional semantics for multiple focus constructions. In Informationsstruktur und Grammatik, ed. Joachim Jacobs, 17–53. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Kuno, Susumu. 1999a. The syntax and semantics of the dake and shika constructions. In Harvard working papers in linguistics, Vol. 7, 144–172.

Kuno, Susumu. 1999b. Dake/shika koobun no imi to koozoo [The syntax and semantics of the dake and sika constructions]. In Gengogaku to nihongo kyooiku [Linguistics and Japanese language education], ed. Yukiko Alam Sasaki, 191–319.

McCready, Elin. 2019. The semantics and pragmatics of honorification: Register and social meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nakanishi, Kimiko. 2006. Even, only, and negative polarity in Japanese. In Semantics and linguistic theory, Vol. 16, 138–155. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v16i0.2953.

Nakanishi, Kimiko, and Hotze Rullmann. 2009. Epistemic and concessive interpretations of at least. Paper presented at meeting of the Canadian Linguistics Association, Carleton University, Ottawa, May 24, 2009.

Numata, Yoshiko. 2000. Toritate [Reference to alternatives]. In Toki/hitei to toritate [Time, negation, and focus], eds. Yoshio Nitta and Takashi Masuoka, 151–216. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Oshima, David Y. 2015. Focus particle stacking: How a contrastive particle interacts with ONLY and EVEN. Paper presented at Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics 11, University of York, June 2015.

Oshima, David Y. 2016. The meanings of perspectival verbs and their implications on the taxonomy of projective content/conventional implicature. In Proceedings of semantics and linguistic theory 26, 43–60. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v26i0.3789.

Oshima, David Y. 2020. The English rise-fall-rise contour and the Japanese contrastive particle wa: A uniform account. In Japanese/Korean linguistics, eds. Shin Fukuda, Shoichi Iwasaki, Sun-Ah Jun, Sung-Ock Sohn, Susan Strauss, and Kie Zuraw, Vol. 26, 165–175. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Oshima, David Y. 2021. When (not) to use the Japanese particle wa: Groundhood, contrastive topics, and grammatical functions. Language 97: 320–340. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2021.0073.

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Revised 2003 UC Santa Cruz dissertation].

Prince, Ellen F. 1986. On the syntactic marking of presupposed open propositions. In Proceedings of the 22nd meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 208–222.

Roberts, Craige. 1996. Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. In OSU working papers in linguistics, Vol. 49, 91–163. [Amended version reissued as Roberts 2012].

Roberts, Craige. 2012. Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics 1(Art. 6): 1–69. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.5.6.

Rooth, Mats. 1999. Association with focus or association with presupposition. In Focus: Linguistic and cognitive, and computational perspectives, eds. Peter Bosch and Rob van der Sandt, 232–244. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taglicht, Josef. 1984. Message and emphasis: On focus and scope in English. London: Longman.

Teramura, Hideo. 1991. Nihongo no shintakusu to imi [Syntax and meaning of Japanese], Vol. 3. Tokyo: Kurosio Publishers.

Tonhauser, Judith, David Beaver, Craige Roberts, and Mandy Simons. 2013. Toward a taxonomy of projective content. Language 89: 66–109. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2013.0001.

van Rooij, Robert, and Katrin Schulz. 2007. Only: Meaning and implicature. In Questions in dynamic semantics, ed. Maria Aloni, Alastair Butler, and Paul Dekker, 193–224. Leiden: Brill.

Velleman, Dan Bridges, David Beaver, Emilie Destruel, Dylan Bumford, Edgar Onea, and Elizabeth Coppock. 2012. It-clefts are it (inquiry terminating) constructions. In Proceedings of SALT 22, 441–460.

Velleman, Leah, and David Beaver. 2014. Question-based models of information structure. In The Oxford handbook of information structure, eds. Caroline Féry and Shinichiro Ishihara, 86–107. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yoshimura, Keiko. 2007. What does ONLY assert and entail? Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 3: 97–117. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10016-007-0007-6.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for valuable comments to the two reviewers and the editors Ashwini Deo, Julie Anne Legate, and Line Mikkelsen. Thanks also go to Christopher Tancredi and Edward Haig for help with English data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Oshima, D.Y. Semantic variation in exclusive quantifiers. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 41, 1529–1561 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-022-09566-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-022-09566-x