Abstract

McCarthy (2013) asks whether there are phonological systems necessitating irreducible parallelism in grammar—systems requiring that multiple changes to the input apply in parallel, in a single derivational step. Such systems would necessitate a framework with lookahead: the ability to see from a given derivational step the results of applying multiple changes to its input. This article makes the following claims: (i) a variety of systems across languages, involving a diverse array of processes, require lookahead; (ii) these systems share the same underlying character, despite superficial differences. Our evidence comes primarily from the distribution of stress, lengthening, and epenthesis in Mohawk; reduplication and hiatus repair in Maragoli; syncope and gemination in Sino-Japanese; and assimilation and epenthesis in Lithuanian. All these systems involve what we call a COMPARISON OF PROCEDURES. To best satisfy constraints, the grammar applies one change followed by another, unless the final result is dispreferred. In such a case, the grammar instead applies a different series of changes. We make the argument for lookahead in grammar by comparing the ability of two frameworks—Parallel Optimality Theory and Harmonic Serialism—to capture these systems. We show that Parallel OT captures them naturally, as it permits lookahead and therefore allows the grammar to compare entire procedures. HS, on the other hand, is challenged by them, as it forbids lookahead and thus does not permit the grammar to compare entire procedures unless the changes involved are specified to apply in a single derivational step. That the problem arises in connection with a diverse array of processes suggests that lookahead is not merely the reflex of a single exceptional phenomenon, but rather is a property of the grammar as a whole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

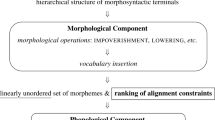

A recurring question in phonology is whether the grammar can see from a given derivational step the complete result of applying multiple changes to its input. Theoretical frameworks differ with regard to whether or not they permit lookahead capability in this sense: it constitutes a central feature in certain frameworks such as Parallel Optimality Theory, Harmonic Grammar and its non-serial versions (Smolensky and Legendre 2006 et seq), and Optimality Theory with Candidate Chains (McCarthy 2007; Wolf 2011 et seq); but other frameworks, including Harmonic Serialism, Serial Harmonic Grammar (Pater 2012 et seq), and traditional versions of SPE (Chomsky and Halle 1968), forbid lookahead, positing derivations and requiring decisions to be made without reference to future derivational steps. In the constraint-based framework of Parallel Optimality Theory (henceforth Parallel OT; Prince and Smolensky 1993/2004), for example, gen can generate candidate outputs that differ from the input by an unbounded number of changes (assign stress, lengthen vowel, spread feature across segments, etc.). All candidates are compared in a single input-output mapping. As a result, the grammar has full lookahead: the ability to base decisions on the result of applying multiple changes to the input. On the other hand, in the serial instantiation of Optimality Theory, Harmonic Serialism (henceforth HS; McCarthy 2010a; McCarthy and Pater 2016, and references therein), gen generates candidate outputs that differ from the input by at most one change. Constraint satisfaction is gradual: each successive input in a series of linearly ordered input-output mappings, or steps, differs from the previous one by at most one harmonically improving change (also called an operation; McCarthy 2010a,b). Within each step, the decision as to which candidate is optimal is made solely based on the candidates present at that step. That is, the grammar has no lookahead—no information about what candidates become available at subsequent steps of the derivation.

McCarthy (2013) asks whether there truly are phonological systems necessitating irreducible parallelism in grammar: that is, systems that require that multiple changes to the input apply in parallel, in a single derivational step. Prince and Smolensky (1993/2004) and McCarthy and Prince (1995) have argued that reduplication-repair phenomena as well as top-down interactions in stress systems necessitate parallel derivation as in Optimality Theory. Recently, however, McCarthy et al. (2016) and McCarthy et al. (2012a) respectively show that the serial framework HS can express top-down interactions and reduplication-repair phenomena. Walker (2010) argued for parallel derivation based on a set of metaphony patterns, but Kimper (2012) shows that HS can derive them too, using constraints independently needed to capture typological generalizations about harmony. Hence, it remains an open question whether grammatical architectures with or without lookahead are more adequate empirically.

This article revives the question of whether the grammar has lookahead, and argues that it does. In particular, we argue that a variety of phonological systems across languages, involving a diverse array of processes, suggest that lookahead is needed in grammar. Moreover, we demonstrate that these cases all share the same underlying character.

To illustrate here the basic thrust of our arguments, we present a stress-epenthesis interaction in Mohawk (Michelson 1988, 1989). In Mohawk, all words have a strictly bimoraic foot (Rawlins 2006 and Adler 2016). In environments where a closed syllable is footed, a monosyllabic foot is built, regardless of whether the syllable is occupied by an underlying or epenthetic vowel (the latter of which is transcribed as [e] below):

-

(1)

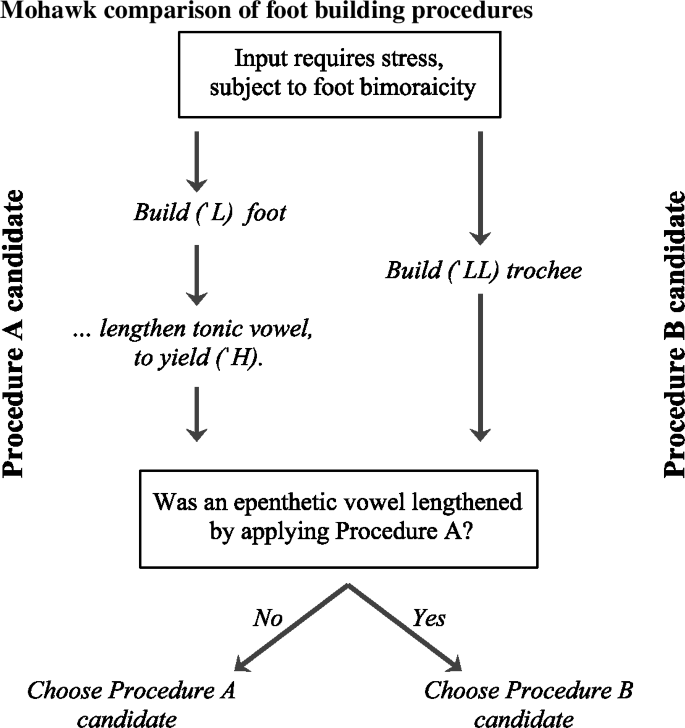

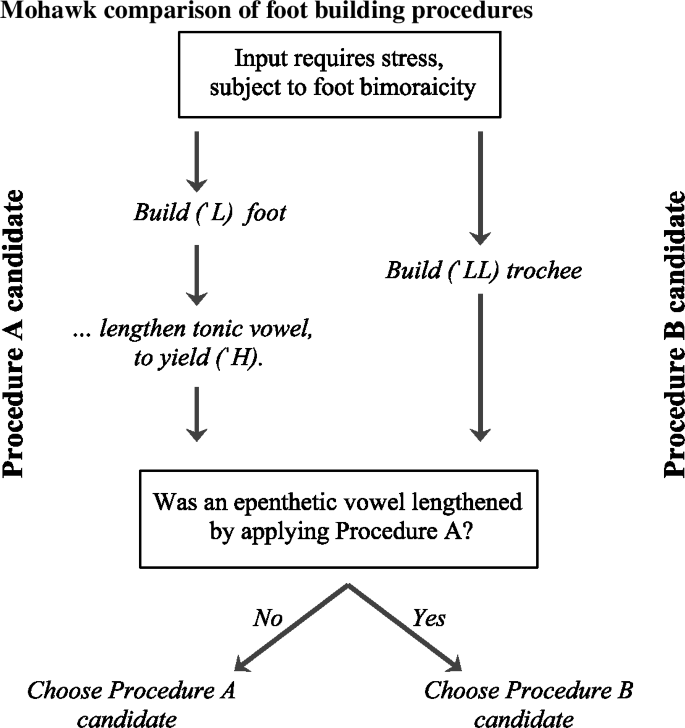

In environments where an open syllable is footed, one of two bimoraic foot shapes is formed, depending on whether the penult vowel is underlying or epenthetic (2). Bimoraic footing is guaranteed through one of two strategies, as shown in the informal serial schema in (3). If the vowel is underlying, then a monosyllabic foot is built, and the tonic vowel is lengthened (3a). But if the vowel is epenthetic, then footing and lengthening would result in a long epenthetic vowel; hence, a disyllabic trochee is built instead (3b). The grammar must therefore look ahead to the result of footing and lengthening to determine which foot shape is to be formed.

-

(2)

-

(3)

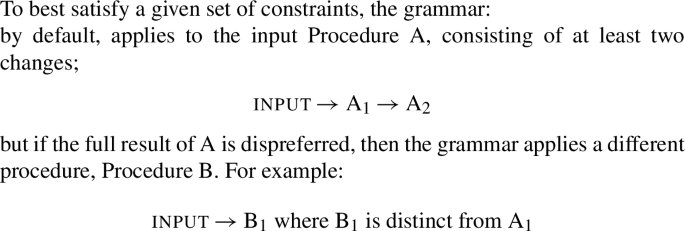

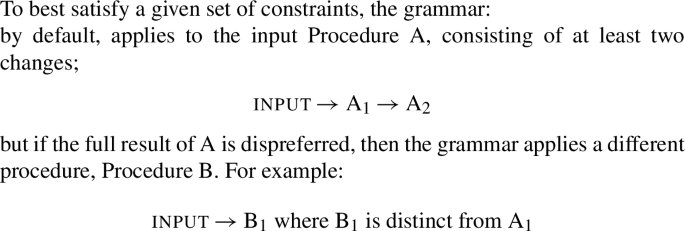

To generalize what we are seeing in (3), we first define the notion of a PROCEDURE: a sequence of zero or more changes applied to the same locus (e.g., footing and then lengthening in Mohawk). A procedure can involve multiple changes, as in (3a) above; or one change, as in (3b); or even zero (see Sect. 5.1 on Sino-Japanese root fusion). The analysis of Mohawk therefore involves what we call a comparison of procedures, as in (4) below. To best satisfy a given set of constraints, the grammar:

-

(4)

An analysis based upon a comparison of procedures requires a theory that permits the grammar to look ahead to the result of applying multiple changes to the input. In particular, the grammar must look ahead to the final result of Procedure A to assess whether a constraint disprefers it, and apply Procedure B in the event that it does.

We claim that, in a number of languages, capturing the distribution of phonological processes requires that the grammar be able to compare entire procedures, and thus be able to look ahead to the result of applying multiple changes to the input. The systems of processes we primarily focus on are stress assignment and epenthesis in Mohawk, reduplication and hiatus repair in Maragoli, deletion and gemination in Sino-Japanese, and assimilation and epenthesis in Lithuanian. We make our argument by comparing the ability of two frameworks—Parallel OT and HS—to capture these systems. We show that Parallel OT captures them naturally, as it crucially permits lookahead and therefore allows the grammar to compare entire procedures. We contend that HS, on the other hand, is challenged by these systems, as it forbids lookahead: due to its gradualness requirement, it does not permit the grammar to compare entire procedures unless the changes involved are allowed to apply in a single derivational step. These changes are therefore irreducibly parallel, in the sense of McCarthy (2013). We examine possible reanalyses of these systems within HS, and show that they either fail to capture the data or miss significant generalizations.

McCarthy (2010b) finds that problematic lookahead phenomena arise in connection with syllabification: for example, in order to determine whether open-syllable syncope should be blocked in Cairene Arabic, the grammar must see whether subsequent resyllabification would result in an illicit structure. He takes this as evidence that lookahead is associated with syllabification in particular, such that only it should be allowed to apply in parallel with other processes. But here, we show that the same lookahead problem arises in connection with a diverse array of phonological processes. The cases suggest that lookahead is not merely the reflex of a single exceptional phenomenon such as syllabification, but rather is a property of the grammar as a whole.

Some of the parallel analyses presented here have been motivated in prior literature, but so far have not been recognized to involve a comparison of procedures, and thus have not been recognized to pose problems for serial derivation. Our discussion of the novel observation that they involve a comparison of procedures is intended to make it easier for other researchers to recognize the need for such comparisons—and thus for a framework with lookahead capability—in other empirical domains.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents data on the distribution of footing, lengthening, and epenthesis in Mohawk, and motivates an analysis for them based on a comparison of procedures. We show that our analysis can be expressed in Parallel OT but not in HS, and further argue that it is superior to alternative serial analyses. In Sect. 3, we provide the abstract schema for a comparison of procedures. The rest of the article shows that a variety of systems across languages, involving a diverse array of processes, each involve a comparison of procedures, fitting into the schema provided in Sect. 3. Section 4 gives an in-depth investigation into the distribution of reduplication and hiatus repair in Maragoli, while Sect. 5 covers syncope and gemination in Sino-Japanese, assimilation and epenthesis in Lithuanian, and other cases. We show that Parallel OT naturally accounts for all cases, but find that HS is challenged by each of them in the same way, due to its gradualness requirement. Section 6 concludes.

2 A comparison of procedures in Mohawk

We introduce the concept of a comparison of procedures with the case of a stress-epenthesis interaction in Mohawk. We argue that the data must be analyzed by comparing two procedures applied to the input—monosyllabic footing together with vowel lengthening, versus disyllabic footing—and that to correctly account for the distribution of these procedures, the grammar must be able to look ahead to the final result of footing and lengthening. In this way, footing and lengthening are irreducibly parallel.

2.1 The data

All Mohawk data come from Michelson (1988, 1989). The page number is indicated next to each datum; page numbers marked with an asterisk are from Michelson (1989), and otherwise Michelson (1988).Footnote 1 To give an overview of the stress-epenthesis interaction, closed penults in Mohawk always receive stress, whether the vowel is underlying or epenthetic. In open penults, if the penult vowel is underlying, then the penult is stressed, and the tonic vowel lengthened. If the penult vowel is epenthetic, then the antepenult is stressed, and no tonic vowel lengthening occurs.

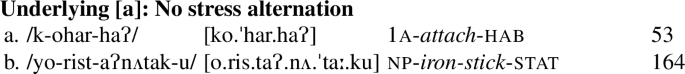

We first describe basic Mohawk stress. If an underlying vowel occupies the penult, then the penult receives stress. If the penult is closed, then no other stress-related processes take place (5). If the penult is open, then the tonic vowel is lengthened (6). Note that vowel length is predictable in Mohawk, with vowels surfacing as long only in certain prominent open syllables, and short elsewhere (see Michelson 1988:65).

-

(5)

-

(6)

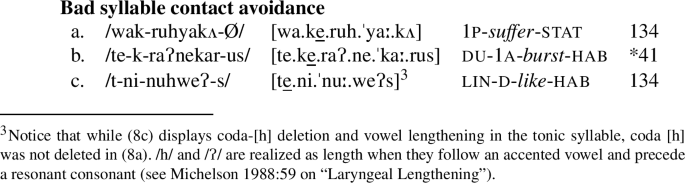

As for epenthesis, [e] is inserted between the first two members of sequences of three consonants (7), and between oral consonant-sonorant sequences (8) (Michelson op. cit.). (For readability purposes, we transcribe epenthetic vowels in Mohawk with an underline.) Like Rawlins (2006), Houghton (2013), and Elfner (2016), we analyze epenthesis in these environments, respectively, as avoidance of complex consonant clusters violating the Sonority Sequencing Principle (Steriade 1982; Selkirk 1984; Clements 1990, a.o.), and avoidance of rising sonority across syllable boundaries (i.e., the Syllable Contact Law; Murray and Vennemann 1983; Davis and Shin 1999; Rose 2000; Gouskova 2004 et seq).Footnote 2

-

(7)

-

(8)

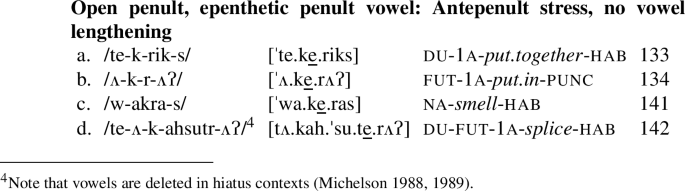

Epenthesis interacts with stress when [e] is inserted into the penult. If [e] occupies a closed penult, the penult gets stressed (9). If [e] occupies an open penult, however, the antepenult gets stressed (10). Finally, if the antepenult is open, the tonic vowel does not lengthen, but rather stays short.

-

(9)

-

(10)

Note that the evidence for morpheme-internal epenthesis in (10c-d) is that such forms pattern like those with epenthesis at morpheme boundaries (e.g. 10a-b) with respect to stress (Michelson 1988, 1989). In (11), for example, [e] alternates for length rather than stress in closed versus open syllables, which is typical of underlying vowels. In (12), however, [e] alternates with stress rather than length, which is typical of epenthesis.Footnote 3

-

(11)

-

(12)

2.2 The Mohawk comparison of foot-building procedures

Summarizing from above, closed penults in Mohawk always receive stress, whether the penult vowel is underlying (13a) or epenthetic (13b). In open penults, if the penult vowel is underlying, then the penult is stressed, and the tonic vowel is lengthened (13c). If the penult vowel is epenthetic, the antepenult is stressed, and no tonic vowel lengthening occurs (13d). Rawlins (2006) provides an elegant analysis of these facts in terms of the choice between two types of a bimoraic trochee, (ˈH) and (ˈL.L) (Mester 1994; Hayes 1995; McCarthy and Prince 1993b). For the extended defense of the bimoraic trochee in Mohawk, see Rawlins (2006) and Adler (2016).

-

(13)

Informally, Rawlins’s Parallel OT analysis is as follows. A constraint demanding strictly bimoraic feet is undominated. Normally, this constraint is satisfied by a penult (ˈH), with coda consonants (13a-b) and vowel lengthening (13c) supplying the second mora. But when a constraint against long epenthetic vowels disfavors (ˈH) (e.g. *[te(ˈkeː)riks]), an (ˈL.L) trochee is built instead (13d).Footnote 4 Rawlins’s analysis involves a COMPARISON OF PROCEDURES (formally defined in Sect. 3): to assess the optimal open penult form, the grammar must compare the final result of applying monosyllabic footing and lengthening to the result of applying disyllabic footing (14). Procedure A consists of monosyllabic footing and vowel lengthening (/k-haratat-s/ → [kha(ˈraː)tats]), while Procedure B consists of disyllabic footing (/te-k-rik-s/ → [(ˈte.ke)riks]). Procedure A applies by default, unless the result is a long epenthetic vowel, in which case Procedure B applies.

-

(14)

In the following sections, we show that this analysis is easily expressed in Parallel OT, in which changes apply simultaneously, but is recalcitrant in HS, in which changes apply successively.

2.3 Mohawk in Parallel OT

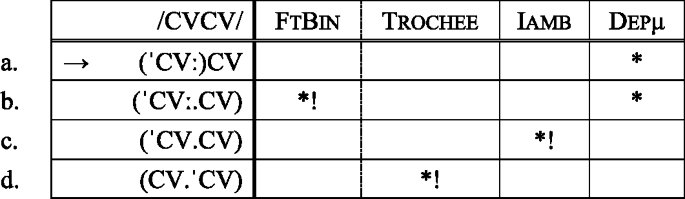

The Mohawk comparison of foot building procedures is straightforwardly expressed in Parallel OT, using the constraints below. We follow Rawlins (2006) in employing FtBinμ, which expresses the preference for bimoraic feet, i.e. (ˈH), (ˈL.L) or (L.ˈL) (15a; Prince and Smolensky (1993/2004); definition from Rawlins 2006; Broselow 2008). We hereafter label this constraint FtBin.

-

(15a)

FtBinμ:

Assign a violation for each foot having more or less than two morae.

(hereafter FtBin)

To derive the basic preference for (ˈH) over the other bimoraic feet, we follow Rawlins in employing FtHdR and FtHdL. FtHdL demands alignment of the left edge of the foot head with the left edge of a foot, and FtHdR demands alignment of the right edge of the foot head with the right edge of a foot (15b–c; e.g., Prince and Smolensky (1993/2004); McCarthy and Prince 1993a; Féry 1999; Rawlins 2006). We hereafter label these constraints as Trochee and Iamb respectively.

-

(15b)

FtHdL:

Assign a violation for every syllable intervening between the left edge of the foot head and the left edge of the foot.

(hereafter Trochee)

-

(15c)

FtHdR:

Assign a violation for every syllable intervening between the right edge of the foot head and the right edge of the foot.

(hereafter Iamb)

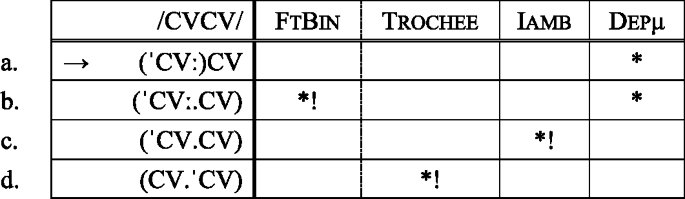

Trochee and Iamb together have the effect of rendering (ˈH) preferable to (ˈL.L) and (L.ˈL) (16). Depμ is the low-ranked, violated constraint that militates against vowel lengthening in (ˈH) feet.

-

(16)

Note that Trochee is omitted from all subsequent tableaux; it is undominated and unviolated by all optimal candidates. We also do not include the losing iambic candidate, (L.ˈL).

We employ a few other constraints and rankings to capture other facts about Mohawk stress. NonFinality (i.e., no head of the prosodic word is final; Prince and Smolensky (1993/2004)) >> Align-R(Ft, PWd) >> Align-L(Ft, PWd) accounts for the rightward orientation of the foot with respect to the word, taking into account the avoidance of word-final feet (17). We hereafter label these constraints as NonFin, AlignR, and AlignL.

-

(17)

Moving on from stress, *Complex and SyllableContact (hereafter SyllCon) >> DepV chooses candidates with epenthesis into triconsonantal sequences (18) and oral consonant-sonorant sequences (19), respectively.

-

(18)

-

(19)

Finally, we follow Rawlins (2006) in interpreting avoidance of stressing epenthetic vowels in open syllables as avoidance of long epenthetic vowels (20) (see Urbanczyk 1996 for an argument that short vowels are relatively unmarked, as well as Ali et al. 2008; Gouskova and Hall 2009 for studies suggesting that epenthetic vowels tend to be shorter than even their short lexical counterparts). Following Rawlins (2006), we express this avoidance as a conjoined constraint against inserting two moras in the domain of the syllable—but hereafter, we label this constraint as DepVː.

-

(20)

Moving on to the ranking, if an underlying vowel occupies an open penult, then the (ˈH)-building procedure applies (/k-haratat-s/ → [kha(ˈraː)tats]) (21). This is captured with FtBin, Iamb >> Depμ.

-

(21)

If an epenthetic vowel occupies an open penult, then (ˈL.L) is formed (/te-k-rik-s/ → [(ˈte.ke)riks]). DepVː >> Iamb rules out (ˈH) (22a∼b), while FtBin >> Iamb rules out (ˈL) (22a∼c). (Finally, AlignR >> Depμ rules out antepenult (ˈH) (22a∼d).)

-

(22)

Thus, DepVː, FtBin >> Iamb successfully captures the choice between the two bimoraic foot-building procedures in Parallel OT.

As a final remark, forms with underlying vowels (/k-atirut-haʔ/ → [kati(ˈrut)haʔ]) or epenthetic vowels (/wak-nyak-s/ → [wa(ˈken)yaks]) in a closed penult are trivially derived using the constraints and rankings already motivated. Neither profile could result in a long epenthetic vowel, and so (ˈH) surfaces on the penult, satisfying FtBin, Trochee and Iamb, and violating AlignR minimally to satisfy NonFin.

2.4 Mohawk in Harmonic Serialism

In this section, we show that under no ranking of the constraints introduced in Sect. 2.3 can HS express the comparison of bimoraic foot-building procedures. We make a proof by contradiction (McCarthy 2010b): the ranking needed to derive forms undergoing one procedure contradicts the ranking needed to derive forms undergoing the other.

In HS, the (ˈH)-building procedure requires two steps (cf. McCarthy 2008; Pruitt 2012). First, a monomoraic foot is built (23a), and then lengthening takes place (23b).

-

(23)

For CV(ˈCV)CV to win at Step 1, it must beat (ˈCV.CV)CV. Because the former has a (ˈL) foot while the latter (ˈL.L), the former can only win if FtHdR outranks FtBin (24).

-

(24)

Iamb >> FtBin expresses a preference for (ˈL) over (ˈL.L) feet. This ranking was not required in the Parallel OT derivation, and it contradicts Rawlins’s (2006) proposal that FtBin is strictly undominated. Nonetheless, the derivation converges on the correct form; in Step 2, FtBin chooses (25a).

-

(25)

The derivation of (ˈH) entails Iamb >> FtBin. While this ranking does not make the wrong prediction for (ˈH)-forms, the opposite ranking is required for the derivation of (ˈL.L)-forms (26). For the candidate in (26b) to win, FtBin must rank above Iamb. Thus, the derivations of (ˈL.L) versus (ˈH) entail a ranking paradox between Iamb and FtBin.Footnote 5

-

(26)

DepVː cannot play the role of eliminating the monosyllabic candidate (26a), as it is not violated in this step. Rather, only in the following step, when lengthening does apply, is DepVː violated (27a).Footnote 6 But at this point in the derivation, it is too late to select (ˈL.L), as (ˈH) was already chosen. Either (27a) or (27b) will win, depending on the relative ranking of FtBin and DepVː, but neither outcome is desirable (as indicated by the two bombs).

-

(27)

In other words, the grammar cannot see from Step 1 that subsequent lengthening would result in a long epenthetic vowel. Thus, footing and lengthening must apply in the same step, so that the (ˈH)-building procedure and the (ˈL.L)-building procedure can be compared, and their distribution derived. That is, footing and lengthening are irreducibly parallel.

2.5 Counter-analyses: In defense of Mohawk as a comparison of procedures

In the previous section, we showed that the analysis of Mohawk based on comparing bimoraic foot-building procedures is incompatible with HS. In this section, we show that a prior alternative serial analysis of the phenomenon falls short in capturing data treatable by the Parallel OT analysis. Elfner (2016) gives an HS-based analysis of the stress-epenthesis interaction using different representations. Under this approach, the underlying presence of a CCC cluster (e.g. /wak-nyaks/, [waˈkenyaks]) versus a CR cluster (e.g. /wak-ras/, [ˈwakeras]) determines the differing locations of stress in cases with [e]-epenthesis. While both Elfner’s serial approach and Rawlins’s parallel approach can capture the interaction between stress and [e]-epenthesis, here we argue that only Rawlins’s approach extends to a further set of data on [a]-epenthesis, introduced below. This supports the claim that the stress-epenthesis interaction is best accounted for by comparing whole procedures, as in the parallel approach.

Elfner (2016) offers an analysis of Mohawk stress couched within HS. Following Michelson’s (1988, 1989) rule-based analysis, Elfner analyzes the variable location of stress in Mohawk to be the result of differential ordering of epenthetic processes relative to stress assignment. Epenthesis into CCC clusters occurs before stress assignment, yielding penult stress, while epenthesis into Cr clusters occurs after stress assignment, yielding antepenult stress (28).

-

(28)

This analysis is naturally expressed in HS. The constraint driving CCC-insertion, *Complex, outranks the constraint driving stress application, PwdHd. This ranking compels insertion before stress assignment at Step 1 (29). In the following step, stress application applies (30).

-

(29)

-

(30)

The constraint driving Cr-insertion, SyllCon, is ranked below PwdHd. Thus, penult stress assignment occurs at Step 1 (31). At Step 2, epenthesis occurs, resulting in antepenult stress (32).

-

(31)

-

(32)

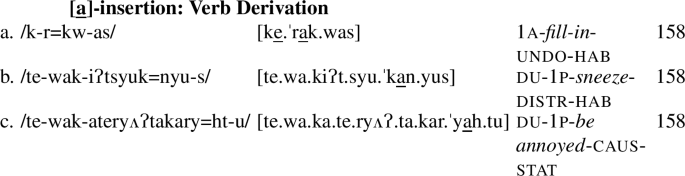

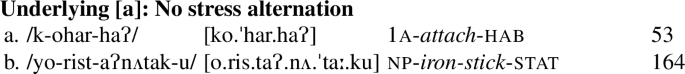

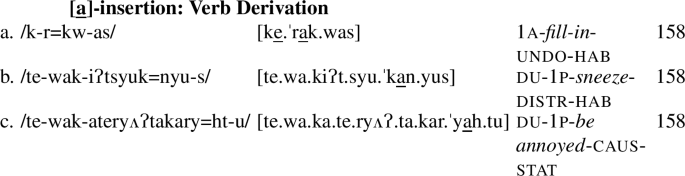

Elfner demonstrates a novel application of HS, deriving the above data using opaque derivations in which the surface stress position differs from the position of stress at the point of application. Nonetheless, a process of [a]-insertion demonstrates that the choice of foot types, rather than opacity, drives Mohawk stress.

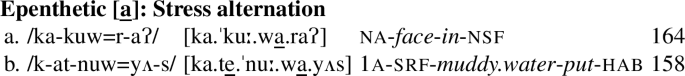

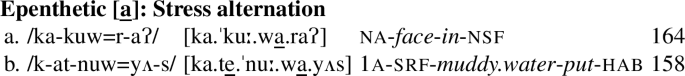

[a] is inserted to break up any consonant clusters surrounding the noun-verb boundary in noun incorporation (33), and the boundary between a verb and a derivational suffix (34) (Michelson op. cit.).

-

(33)

-

(34)

Evidence that [a] must be epenthetic, rather than underlying, is that [a] patterns like an epenthetic vowel, rather than underlying [a], with respect to stress ((35) versus (36)).Footnote 7

-

(35)

-

(36)

With respect to stress, [a] patterns nearly exactly like [e] with respect to the openness versus closedness of syllables. In particular, if [a] occupies a closed penult, the penult is stressed (37). If [a] occupies an open penult, the antepenult is stressed (38). The one difference between [a]- and [e]-epenthesis is that if [a] occupies an open penult, then tonic-vowel lengthening takes place, even though it does not in [e]-epenthesis (e.g., [ka.ˈkuː.wa.raʔ] versus [ˈte.ke.riks]). ADLER (2016) provides an analysis of this asymmetry in terms of avoidance of highly sonorous [a] in the non-head of a foot (e.g. *[ka(ˈku.wa)raʔ]; see de Lacy 2006).

-

(37)

-

(38)

The fact that [a] and [e] both correlate with antepenult stress when occupying open penults highlights the explanatory failure of the HS account. If the location of stress is due to differential ordering of two epenthetic processes with respect to stress assignment, then there must be two distinct epenthetic processes. For [e]-epenthesis, one could claim that this is the case: [e] is inserted into CCC clusters prior to stress assignment, and into Cr-clusters after stress assignment (as in the derivations in (28) above). The same cannot be said for [a]-epenthesis; there is a single process of insertion into clusters, always at the = boundary. Calling the constraint driving the process *C=C, no ranking of *C=C relative to PwdHd makes the right predictions: *C=C >> PwdHd predicts universally penult stress (/k-at-nuw=yʌ-s/ → kat.nu.wa.yʌs → *kat.nu.ˈwa.yʌs; (38a)), while PwdHd >> *C=C universally predicts antepenult stress (/te-wak-iʔtsyuk=nyu-s/ → te.wa.kiʔt.ˈsyu.k=nyus → *te.wa.kiʔt.ˈsyu.kan.yus; (37c)). For the HS account to extend to [a]-epenthesis, one would have to posit arbitrarily different processes of [a]-epenthesis, one post hoc process whose driving constraint is ranked above PwdHd in all cases of penult stress, and another post hoc process whose driving constraint is ranked below PwdHd in all cases of antepenult stress.

The foot-based Parallel OT analysis posits that a surface structure, i.e. the openness versus closedness of the syllable that the epenthetic vowel occupies, predicts the location of stress, while the HS analysis posits that an underlying structure, i.e. the consonant clusters that compel epenthesis, predicts the location of stress. The stress pattern for [a]-insertion shows that the former is borne out: when [a] is in a closed penult, the penult receives stress; and when [a] is in an open penult, the antepenult receives stress.

The Parallel OT analysis we invoke for these forms is nearly the same as the analysis invoked for forms with [e]-epenthesis. We need only a little more to account for emergence of antepenult (ˈH) when [a] occupies an open penult. We define below *Non-HdFt/a (simplified from de Lacy 2006), which encodes the preference for low-sonority segments in the non-head position of a foot (39). A tableau for these forms is given in (40) below. *Non-HdFt/a >> AlignR prefers a less right-aligned foot over leaving [a] in the non-head position of a foot (40a∼b).Footnote 8DepVː >> AlignR prefers a less right-aligned foot over a long epenthetic vowel (40a∼d), while FtBin >> AlignR prefers a less right-aligned foot over (ˈL) (40a∼c).

-

(39)

-

(40)

The closed-penult forms with [a] are accounted for in the same way that other forms with a closed penult are: [a] does not lengthen, and so (ˈH) surfaces on the penult, satisfying FtBin, Trochee and Iamb, and violating AlignR minimally to satisfy NonFin.Footnote 9

2.6 Summary

This concludes our discussion of Mohawk stress. We have argued for: 1) the necessity of an approach to the data that relies on a comparison of procedures to adequately express the generalizations underlying the stress-epenthesis interaction; 2) the necessity of lookahead in grammar to express this comparison of procedures, by comparing the Parallel OT analysis against the relatively unsuccessful HS analysis. Moreover, we show that an HS reanalysis nevertheless fails to solve aspects of the stress-epenthesis interaction. See Adler (2016) for the full Parallel OT analysis, which argues for the necessity of the bimoraic foot to capture basic stress, [e]-epenthesis, [a]-epenthesis and so-called subminimal word augmentation.

3 The general form of a comparison of procedures

The Mohawk stress system is readily analyzable in Parallel OT, but recalcitrant in HS. As we argue in Sect. 2.2, this is because an adequate analysis of the system involves a COMPARISON OF PROCEDURES: the grammar applies to the input a series of changes, unless the result is dispreferred; in such a case, the grammar applies a different series of changes. We define in (41) a schema for one such case of a comparison of procedures.

-

(41)

Note that Procedure A must consist of at least two changes, whereas Procedure B may consist of zero or more. The key point is that the grammar must be capable of assessing the result of Procedure A and of rejecting at least two of its changes in favor of the distinct result of Procedure B.

In constraint-based terms, one or more constraints drive a set of inputs to undergo Procedure A or B (e.g., FtBin in Mohawk drives the formation of some type of bimoraic foot). Procedure A applies by default, forced by some constraint that prefers it to Procedure B (e.g., Iamb in Mohawk, which prefers (ˈH) formation to (ˈL.L) formation). But for some inputs, the result of applying the entirety of Procedure A would violate another constraint—which we can call the blocking constraint—more than applying B would; in this case, B applies instead (e.g., DepVː in Mohawk blocks (ˈH) formation when it would lengthen an epenthetic vowel, in which case (ˈL.L) is formed). In this scenario, candidates displaying entire procedures of changes must be compared: one displaying the full result of A—that is, multiple changes applied to the input—and one displaying the result of B, with A chosen unless the blocking constraint prefers B, in which case B is chosen. This scenario is depicted in the schema in (42) below. Every case discussed in this article is argued to have this structure: each involves a comparison of procedures.

-

(42)

An analysis based upon a comparison of procedures requires a theory that permits the grammar to look ahead to the result of applying multiple changes to the input. A number of previously proposed frameworks are capable of expressing comparisons of procedures, including Parallel OT, Harmonic Grammar and its non-serial varieties (Smolensky and Legendre 2006 et seq), and OT with Candidate Chains (McCarthy 2007; Wolf 2011 et seq). In Parallel OT, for example, multiple changes apply to the input in a single derivational step, and so the grammar has access to whether the fully formed Procedure A candidate violates the blocking constraint, and so can select the Procedure B candidate in case it does. On the other hand, serial frameworks that do not permit lookahead cannot express a comparison of procedures. Examples include HS, classical SPE (Chomsky and Halle 1968), and Serial Harmonic Grammar (Pater 2012 et seq). In HS, for example, Procedure A changes apply one at a time, and the grammar cannot look ahead to subsequent steps to assess whether the result of fully applying A would violate the blocking constraint. In theories forbidding lookahead, then, cases claimed to involve a comparison of procedures must be reanalyzed. If no such analysis exists, or if the subsequent non-lookahead analysis fails to reflect using well-established concepts the insights that the lookahead analysis reflect, then the data would constitute evidence for theories that permit lookahead.

In the following sections, we present a variety of cases across languages that are straightforwardly described as involving comparisons of procedures. Like Mohawk, these cases are captured in Parallel OT, but lack an HS analysis that reflects the insights achieved by the lookahead analysis. They involve a diverse array of phonological processes, and so suggest that lookahead is not merely restricted to a single exceptional process applying in parallel with others, but rather is a property of the grammar as a whole.

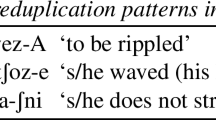

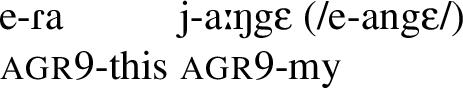

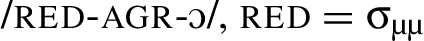

4 Paradoxical ordering of reduplication and glide formation in Maragoli

We first present a case, previously unreported in published literature, from Maragoli, a Bantu language spoken primarily in Kenya. A reduplication-repair interaction observed in the possessive paradigm in the language is straightforwardly described as involving a comparison of procedures, and thus constitutes evidence for lookahead in grammar. The language repairs stem hiatus prior to copying, unless the result is a complex onset; in such a case, copying applies first, and then hiatus repair. We summarize the case below, but for the full set of data, thorough analysis of them, and evidence for the psychological reality of the data patterns, see Zymet (2018).

4.1 The data

The Maragoli data were obtained from a native Maragoli speaker in a UCLA Field Methods class in the winter of 2015. Some of the data below are also given in Leung (1991). In all cases where a form obtained in the class was also found in Leung (1991), the match was perfect.

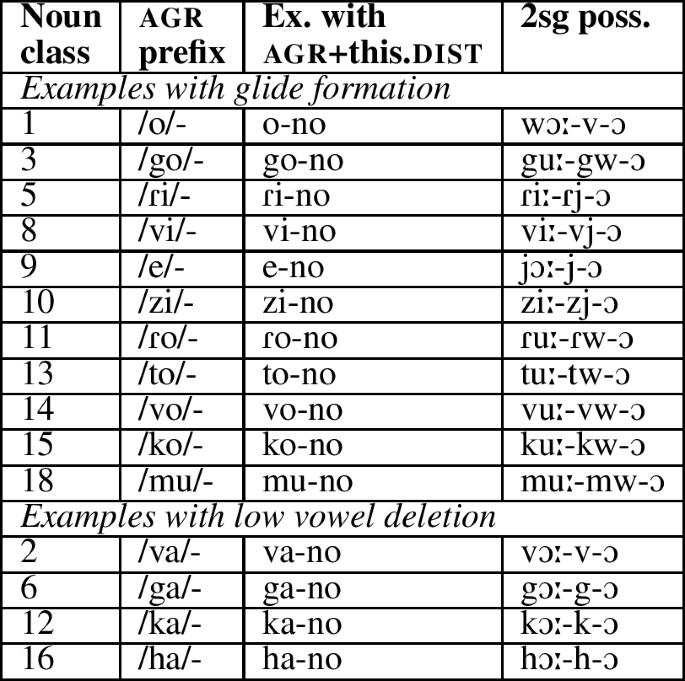

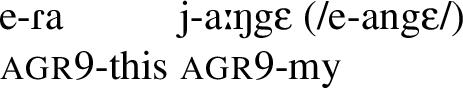

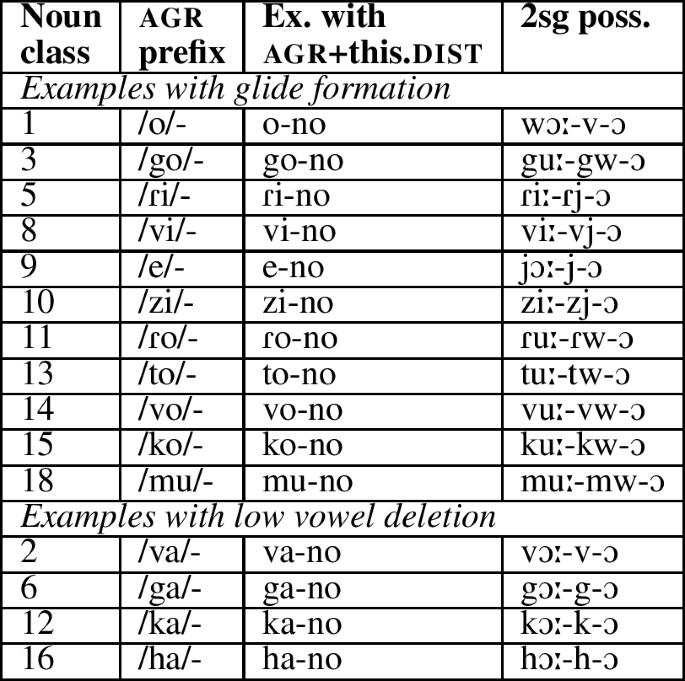

Maragoli has two productive, entirely systematic hiatus repairs: glide formation (43a-d) and low vowel deletion (44a-b). We illustrate the processes as they apply to various noun-class and noun-class agreement prefixes in the language. Glide formation applies to the agreement prefixes given below when they come before vowels (43a-d). /i e/ and /o u/ surface as [j] and [w], respectively, neutralizing the height contrast between the vowel pairs.Footnote 10

Glide formation

-

(43)

-

(43)

-

(43)

-

(43)

Low vowel deletion applies to the noun-class and noun-class agreement prefixes in (44a-b), so that /a/ elides before vowels:

Low vowel deletion

-

(44)

-

(44)

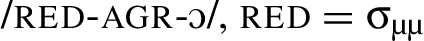

In addition to hiatus repair, the language also has a process of reduplication to mark second- and third-person singular possessive categories in the language.Footnote 11 (45) displays examples of the possessive paradigm. Note that since all reduplicated forms occur in tandem with hiatus repair, it is impossible to show reduplication in isolation. Second- and third-person singular possessives are characterized by a one-to-many mapping between meaning and form: possession is realized as both a reduplicative prefix and a fixed-segment suffix (see Stonham 1994; Downing and Inkelas 2015 for a similar pattern in Nitinaht, and Mathangwane and Hyman 1999 for the same pattern in Kalanga). In second-person singular possessives, this fixed-segment suffix is -ɔ, and in third-person possessives, -ε. red in the glosses below foreshadows the OT-based analysis developed in the next section, in which we follow McCarthy and Prince (1986/1996) in assuming that material is copied into reduplicants: morphemes consisting of empty prosodic templates present in the input.

-

(45)

To explicate our point about lookahead in Maragoli possessives, it suffices to examine the behavior of only the second-person forms. We set aside third-person forms for purposes of brevity (see Zymet 2018 for the account). We first present in (46) the general structure of the underlying forms of the second-person singular possessives, and in (47a-b) two representative examples to be analyzed throughout the remaining discussion. We take the reduplicant in these data to be located word-initially. The reduplicant vowel is long, which we account for by specifying that the reduplicant is underlyingly bimoraic.Footnote 12

-

(46)

-

(47)

-

(47)

In (47a), the input undergoes glide formation followed by copying (red-e-ɔ → red-j-ɔ → jɔː-j-ɔ); in (47b), applying glide formation followed by copying would result in a complex reduplicant onset (red-vi-ɔ → red-vj-ɔ → *vjɔː-vj-ɔ), and so the input undergoes copying first, and then glide formation (red-vi-ɔ → viː-vi-ɔ → viː-vj-ɔ). Finally, in (47c) below we present a third representative example to be later discussed in the context of the lookahead debate:

-

(47)

The example here undergoes low vowel deletion rather than glide formation, but otherwise can be described in the same way that (/red-e-ɔ/, [jɔː-j-ɔ]), as in (47a), can: the input undergoes deletion followed by copying (red-ga-ɔ → red-g-ɔ → gɔː-g-ɔ).

In (48), we present the full set of second-person singular possessives involving glide formation or low vowel deletion, of which the upcoming Parallel OT analysis gives a general account.Footnote 13 We also give examples of the agreement prefix preceding the distal demonstrative to elucidate their underlying forms.

-

(48)

4.2 Maragoli reduplication and repair as a comparison of procedures

The central argument here is that a satisfactory account of Maragoli possessives involves a comparison of procedures, and thus necessitates a framework that permits lookahead such as Parallel OT. We illustrate this in (49a-b) using informal, schematic derivations of the two previously discussed examples involving reduplication and glide formation, (/red-vi-ɔ/, [viː-vj-ɔ]) and (/red-e-ɔ/, [jɔː-j-ɔ]). In (49a), on the one hand, glide formation takes place before copying to derive [jɔː-j-ɔ] from /red-e-ɔ/:

-

(49)

In (49b), on the other hand, copying must take place before glide formation, to derive [viː-vj-ɔ] from consonant-initial /red-vi-ɔ/. This ensures a simplex onset in the reduplicant, avoiding the extra complex onset in *[vjɔː-vj-ɔ].

-

(49)

This Maragoli reduplication-repair interaction, then, crucially involves a comparison of procedures. The data can be described as follows: the input undergoes hiatus repair followed by copying, unless the result is a complex onset; in that case, copying applies first, and then repair.Footnote 14 In more OT-oriented terms, hiatus repair and copying apply to a given input in whichever way yields a simplex reduplicant onset. We now turn to a Parallel OT analysis of these possessives.

4.3 Maragoli in Parallel OT

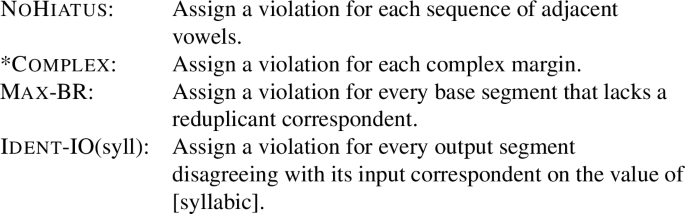

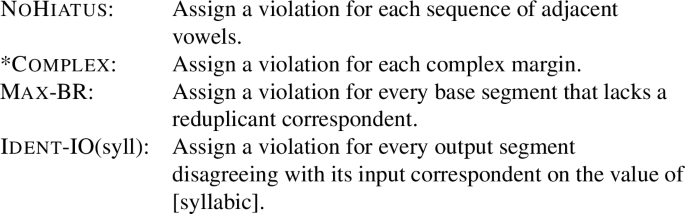

We illustrate below the Parallel OT analysis of the three representative possessives given in the prior section: two that show glide formation—(/red-vi-ɔ/, [viː-vj-ɔ]) and (/red-e-ɔ/, [jɔː-j-ɔ])—and one that shows low vowel deletion (/red-ga-ɔ/, [gɔː-g-ɔ] red-agr6-your). In Parallel OT these possessives are easy to capture, as it permits the grammar to look ahead and assess the results of applying multiple changes to the input: copying and repair apply in one fell swoop, in whichever way best satisfies onset well-formedness constraints. The data can be accounted for straightforwardly with markedness constraints and faithfulness constraints enforcing input-output and base-reduplicant correspondence (BR-correspondence; see McCarthy and Prince 1995, 1997 for an introduction) (50). We focus on the forms showing glide formation first. NoHiatusFootnote 15 and Max-BR drive hiatus repair and copying. Max-BR prefers a complete copy of the base to a partial copy ([j1ɔː2-j1-ɔ2] ≻Max-BR *[eː1-j1-ɔ2]). *Complex blocks full copying where it would yield an extra complex onset; in such a case, partial copying takes place ([v1iː2-v1j2-ɔ3] ≻*Complex *[v1j2ɔː3-v1j2-ɔ3]).

-

(50)

The tableaux below illustrate how glide formation and reduplication interact to select (/red-e-ɔ/, [jɔː-j-ɔ]) and (/red-vi-ɔ/, [viː-vj-ɔ]). Max-BR favors full copying (51), but *Complex >> Max-BR favors partial copying where full copying would result in an extra complex onset (52).Footnote 16

-

(51)

-

(52)

Here we see that reduplication and repair apply in a single step, in whichever way best satisfies onset well-formedness constraints—in the above tableaux, *Complex. Parallel OT can capture these data because it permits the grammar to compare the two ways of applying multiple changes to the input.

The analysis requires little more to account for possessives involving low vowel deletion such as (/red-ga-ɔ/, [gɔː-g-ɔ] red-agr6-your). We use MaxV (53), ranked lower than NoHiatus so that low vowel deletion applies to resolve hiatus. We see in (54) that [gɔː-g-ɔ] is like [jɔː-j-ɔ], from (51): when *Complex is not under threat of being violated, we get full correspondence between the stem and reduplicant.

-

(53)

-

(54)

4.4 Maragoli in Harmonic Serialism

McCarthy et al. (2012a) propose a sub-framework within HS, Serial Template Satisfaction, which captures patterns of reduplication and their interaction with phonology. Following McCarthy and Prince (1986/1996), Serial Template Satisfaction posits templatic morphemes, i.e. empty prosodic templates in the input that segmental content is copied into. Many constraint-based analyses in the past have posited base-reduplicant correspondence to drive copying, but because base-reduplicant correspondence plays no role in HS, copying is driven by Headedness(σ) (abbreviated HD in tableaux), which demands that syllables be headed by segmental content (Selkirk 1995). Moreover, since copying segmental content into the template constitutes an operation in HS, copying violates a faithfulness constraint *COPY(seg) (abbreviated as *Copy in the tableaux). These constraints are defined below. For further explanation of these constraints, see McCarthy et al. (2012a).

-

(55)

We thus compare the Parallel OT account and HS account with the same constraints, except that we now use Headedness(σ) and *Copy(seg) in place of Max-BR. Though Serial Template Satisfaction adopts empty prosodic templates as the form of the reduplicant morpheme, Serial Template Satisfaction does not signify red in its underlying forms, and so below we write underlying forms of possessives with /σμμ/ when we discuss these templates in the context of the HS analysis.

Recall that (/σμμ-e-ɔ/, [jɔː-j-ɔ]) requires repair to apply before copying in the serial analysis: σμμ-e-ɔ →σμμ-j-ɔ → jɔː-j-ɔ. To derive this, we must rank NoHiatus above HD (56a-b).

-

(56)

-

(56)

But now since NoHiatus ranks above HD, we can never get the opposite order, namely the reduplication-repair order. To derive [viː-vj-ɔ] from /σμμ-vi-ɔ/, HD must be ranked above NoHiatus so that copying applies before glide formation (57). The situation is analogous to the ordering paradox observed in the schematic rule-based derivations in (49a-b): changes driven by HD and NoHiatus cannot be applied in a fixed series, since both orders are required for the full paradigm. HS misses the generalization that reduplication and repair apply in whichever order yields a simplex onset—onset constraints such as *Complex play no role.

-

(57)

In the second step of the derivation, the grammar would select ∖vjɔː-vj-ɔ∖ or ∖σμμ-vj-ɔ∖ (the latter of which contains an empty reduplicant)—both undesirable intermediate forms—depending on the ranking between HD and *Complex.

The HS account fails to capture the distribution between the repair-reduplication procedure on one hand, and reduplication-repair on the other, as it is unable to look ahead to the results of applying both orders to see which one of them would result in a simplex versus complex onset. Thus, the two processes must be treated as irreducibly parallel: they must apply in the same derivational step in order to capture the distribution between the two conspiring procedures.

4.5 Defense against an HS counteranalysis

A reviewer and an MFM conference audience member posed the question of whether an HS analysis of these data could be made to work if we distinguished word-initial onsetless syllables from onsetless syllables in other positions, so as to derive early repair in (/σμμ-e-ɔ/, [jɔː-j-ɔ], *[eː-j-ɔ]) but early copying in (/σμμ-vi-ɔ/, [viː-vj-ɔ]). Suppose we used in the HS analysis *#V, which penalizes word-initial onsetless syllables (Flack 2009), together with NoHiatus, which penalizes word-internal onsetless syllables. This section argues that such an analysis cannot be made to work, at least without even further modifications to the analysis that render it significantly less insightful than the lookahead analysis.

The data displaying reduplication and glide formation can be accounted for in HS by ranking *#V >> HD >> NoHiatus. In (58a), high-ranking *#V forces repair to apply first to /σμμ-e-ɔ/, yielding the intermediate form ∖σμμ-j-ɔ∖; in the second step of the derivation not shown, HD would force ∖σμμ-j-ɔ∖ to map to ∖jɔː-j-ɔ∖. Moreover, since HD is ranked higher than NoHiatus, forms like /σμμ-vi-ɔ/ would undergo copying first, as in (58b), resulting in the intermediate form ∖viː-vi-ɔ∖; in the second step not shown, repair would apply, yielding ∖viː-vj-ɔ∖ as desired.

-

(58a)

-

(58b)

Problematically, this approach fails to account for cases displaying low vowel deletion such as (/σμμ-ga-ɔ/, [gɔː-g-ɔ]). The data necessitate that repair apply first, but the ranking above results in copying applying first (59). In the second step of the derivation, the wrong intermediate candidate ∖gaː-g-ɔ∖ would be selected to satisfy NoHiatus.

-

(59)

To avoid this outcome, one might resort to breaking NoHiatus into a set of quality-specific hiatus constraints, e.g. *aV and *[-low]V. Then, with the ranking *#V, *aV >> HD >> *[-low]V, we could derive early hiatus repair in (/σμμ-ga-ɔ/, [gɔː-g-ɔ]) via high-ranking *aV, early hiatus repair in (/σμμ-e-ɔ/, [jɔː-j-ɔ]) via high-ranking *#V, and early copying in (/σμμ-vi-ɔ/, [viː-vj-ɔ]) via HD being ranked higher than *[-low]V. But even this analysis suffers a serious drawback. Constraint-based accounts of diverse repairs in Bantu and beyond have utilized a single NOHIATUS constraint as well as a set of lower-ranked faithfulness constraints to determine the repair for a particular hiatus (Rosenthall 1994; Casali 1995, 1997, 1998; Orie and Pulleyblank 1998; Senturia 1998; Baković 2005). Such an approach captures the fact that the various repairs all conspire to avoid the same output structure from surfacing, namely pairs of adjacent vowels. An analysis that posits quality-specific hiatus constraints dismisses this conspiracy as coincidence, failing to capture the broad generalization that these repairs, though diverse, militate against the same output structure.

4.6 Summary

Summing up, we find that the Maragoli system involves comparing whole procedures, suggesting the need for lookahead in grammar. The input undergoes hiatus repair followed by copying, unless the result is a complex onset; in that case, copying applies first, and then repair. Parallel OT can capture these data, as it permits the grammar to look ahead to the result of applying multiple changes to the input, and assess which candidate would result in a simplex reduplicant onset. On the other hand, HS fails to capture these data, because it applies changes one-by-one in a succession of derivational steps, without permitting the grammar to look ahead; it therefore cannot compare the copy-then-repair procedure against the repair-then-copy procedure to determine which one would result in a simplex onset. A reanalysis that merely distinguishes word-initial onsetless syllables fails to capture the entire dataset, while a reanalysis that subsequently adds quality-specific constraints misses the broad generalization that hiatus repairs conspire to avoid the same output structure, namely hiatus.

5 Additional cases involving a comparison of procedures

In addition to the Mohawk stress and Maragoli reduplication systems, there are a number of other phenomena that have previously been convincingly analyzed whose analysis turns out, as we will show, to involve a comparison of procedures. We first discuss Sino-Japanese root fusion, a phenomenon that has received much attention (e.g., Kurisu 2000; Kawahara et al. 2003; Ito and Mester 2015). The widely adopted analysis has so far not been recognized to involve a comparison of procedures, and thus has not been recognized to pose issues for serial derivation. The novel observation that this analysis involves a comparison of procedures sheds new light on the phenomenon itself, and the discussion of this case here is intended to make it easier for other researchers to recognize the need for comparisons of procedures in other empirical domains. We then discuss assimilation and epenthesis in Lithuanian (Baković 2005; Albright and Flemming 2013), and more briefly nasal spreading and deletion in Gurindji (Stanton 2020) and footing, metathesis, and syncope in Maltese (Anderson 2016), and show that each of the analyses previously motivated for these cases involve comparisons of procedures. All of these cases, which involve phonological processes from a diverse set of domains, convincingly necessitate irreducible parallelism, and therefore suggest that derivational lookahead is not merely a property associated with particular phonological processes, but with the grammar as a whole.

5.1 Sino-Japanese root fusion

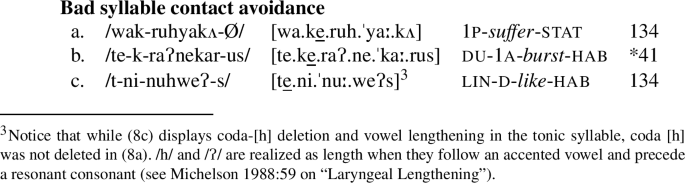

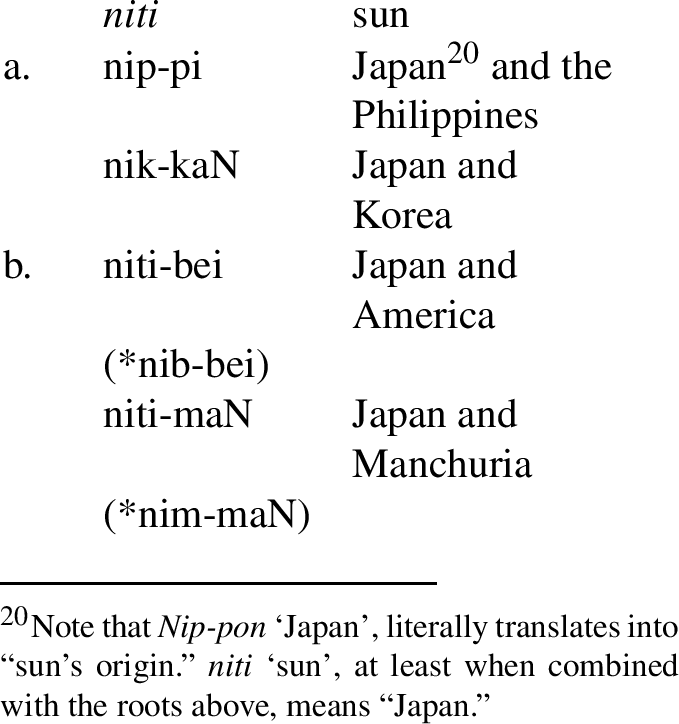

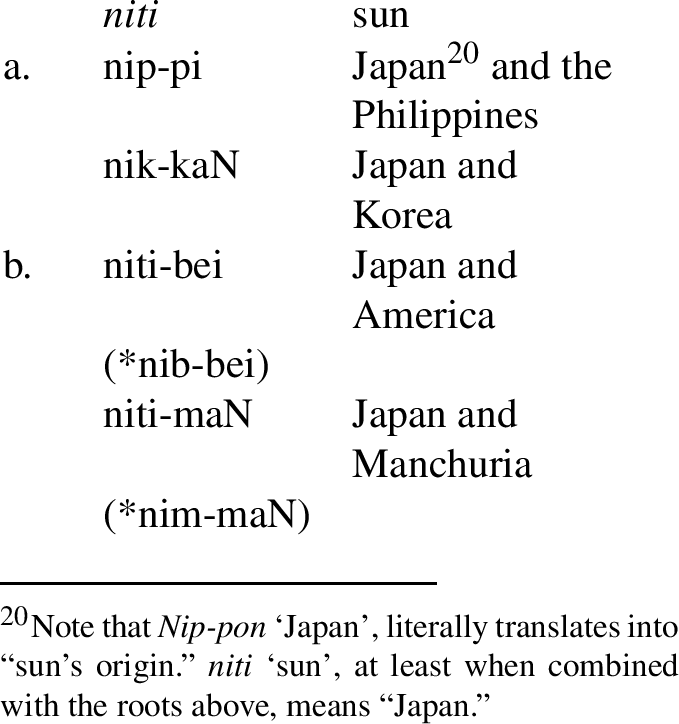

In Sino-Japanese, CVCV roots are commonly compounded together by a procedure called root fusion (Ito 1986; Tateishi 1989; Ito and Mester 1996). Representative forms from Ito and Mester (1996) are given in (69) and (70). The boundary-adjacent vowel deletes, and the resulting consonant cluster undergoes gemination (60a, 61a). But whenever this would produce a voiced geminate, the compound surfaces faithfully (60b, 61b).

-

(60)

-

(61)

The system has been analyzed extensively in Parallel OT (e.g., Kurisu 2000; Kawahara et al. 2003; Ito and Mester 2015), but not in HS. It turns out that the analysis involves a comparison of procedures: apply syncope and gemination unless the result is a voiced geminate; in such a case, do nothing. The data lend support to a framework that permits the grammar to look ahead to the full result of applying vowel syncope and gemination.

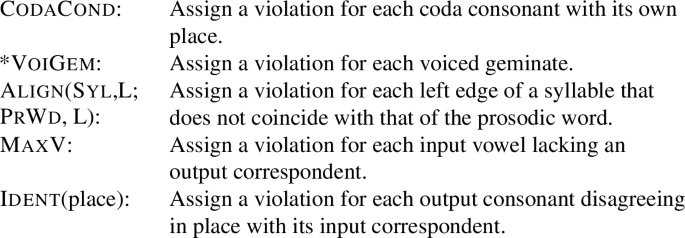

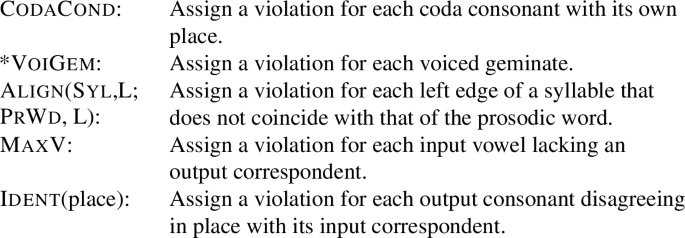

To illustrate the Parallel OT analysis, we adopt the constraints given in Kurisu (2000) (62). Root fusion—that is to say, syncope and gemination—reflects a drive towards small prosodic words and an avoidance of clusters disagreeing in place, expressed by the constraints CodaCond and Align(Syl,L; PrWd, L). Defaulthood of fusion is already enforced by the fact that the other procedure, doing nothing, fails to satisfy Align(Syl,L; PrWd, L). Fusion violates MaxV and Ident(place). The blocking constraint is *VoiGem, violated when fusion results in a voiced geminate.

-

(62)

CodaCond and Align(Syl,L; PrWd, L) (hereafter Align-L) drive root fusion (63), while *VoiGem >> Align-L blocks it when it would result in a voiced geminate (64).

-

(63)

-

(64)

We now turn to the HS analysis. For root fusion to apply at all in HS, CodaCond must be demoted below Align-L (65). But then syncope will always apply, even where it would later yield a voiced geminate (66). *VoiGem plays no role in blocking: the grammar cannot look ahead to determine if root fusion would produce a voiced geminate.

-

(65)

-

(66)

In light of the failed derivation in HS, one might invoke an analysis whereby the roots are underlyingly /CVC/ and the root-final vowel is epenthesized to avoid C# and voiced geminates in compounds. A reviewer brings to light that even the epenthetic analysis raises problems for serialism, as it too involves a comparison of procedures: if the underlying form is /t-g/, for example, then the grammar would have to look ahead to see that assimilating and voicing the first obstruent would result in a voiced geminate, inserting a vowel without applying any changes to the initial obstruent. Moreover, though early work on root fusion posited epenthesis (Ito 1986; Tateishi 1989; Ito and Mester 1996), more recent research has cast doubt on this possibility (Kurisu 2000; Labrune 2012; Ito and Mester 2015, building on Vance 1987): in particular, the quality of the final vowel is not predictable in a class of cases. Kurisu (2000) notes that the debate here is rendered meaningless under Richness of the Base (Prince and Smolensky 1993/2004), which requires that the grammar map inputs to legal surface forms without placing restrictions on underlying forms (so long as contrasts are preserved): the facts can be adequately captured without having to commit to one of the underlying forms, so long as the analysis maps both /CVC/ and /CVCV/ forms to appropriate outputs. With Richness of the Base, we can say that linguistic variation is reduced to differences in constraint ranking, rather than both ranking and input conditions; for HS to be consistent with Richness of the Base, it would have to contend with underlying forms such as /CVC1V-C2VCV/.

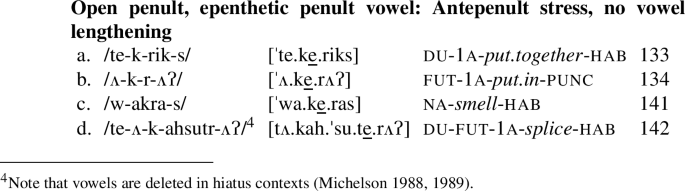

5.2 Lithuanian assimilation-epenthesis

In Lithuanian, the verbal prefixes ap- and at- (67a) generally assimilate in voicing and palatalization to following obstruents (67b), except when full assimilation would produce a geminate. In such a case, epenthesis applies instead, with concomitant palatalization before [i] (67c) (Baković 2005).Footnote 17 Baković develops an analysis of these data in Parallel OT, and Albright and Flemming (2013) shows that the analysis cannot be replicated in HS. We illustrate here why this is the case: the analysis involves a comparison of procedures.

-

(67)

-

(67)

-

(67)

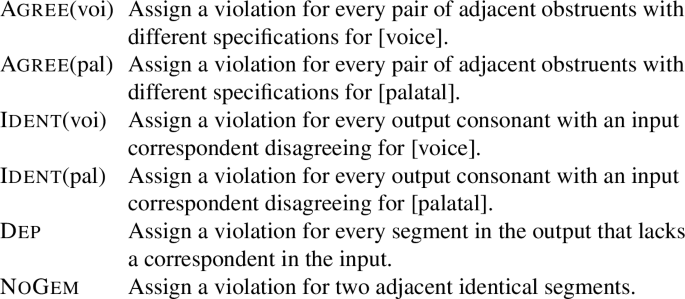

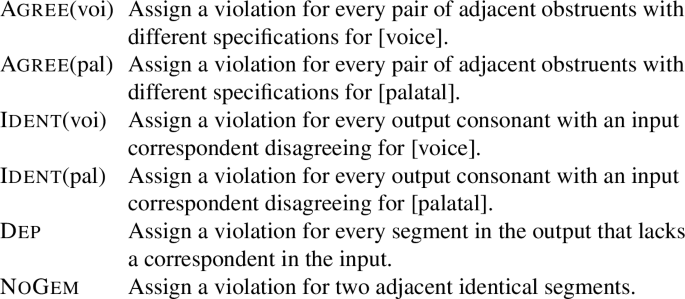

Baković’s account employs the constraints in (68). The Agree constraints drive agreement between adjacent obstruents, Dep disprefers epenthesis, Ident disprefers assimilation, and NoGem prevents geminates from surfacing.

-

(68)

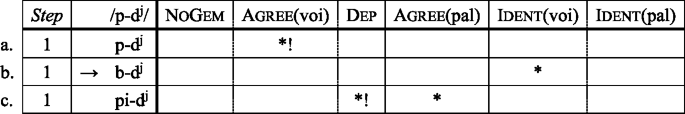

Agree(voi), Agree(pal) >> Faith drives assimilation, with Dep >> Ident selecting full assimilation rather than epenthesis as the default procedure for resolving agreement (69). NoGem >> Dep, however, selects the epenthesis candidate in environments where full assimilation would yield a geminate (70).

-

(69)

-

(70)

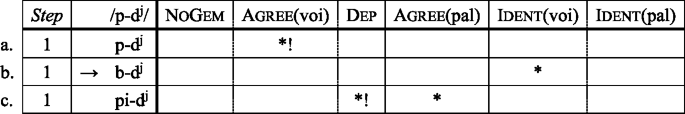

HS cannot capture the distribution of assimilation and epenthesis using Baković’s constraints, provided that voicing and palatalization assimilation apply in separate steps (Albright and Flemming 2013). Assimilation requires two steps to satisfy both Agree constraints, while epenthesis requires only one. Thus, for assimilation to ever apply, at least one of the Agree constraints must be demoted below Dep (71).

-

(71)

The result is that epenthesis will never apply. Because HS cannot look ahead to determine if full assimilation would violate NoGem, it cannot block it from applying (72).

-

(72)

As long as voicing assimilation and palatalization assimilation cannot occur in a single step, HS fails to capture Lithuanian agreement. The assimilatory processes are therefore irreducibly parallel.

One might be tempted to give an HS analysis of epenthesis here in terms of avoidance of sufficiently similar adjacent segments, rather than geminate avoidance. If, for instance, NoGem were replaced with a constraint disfavoring sequences like [pjbj] or [bbj], then epenthesis could apply instead of assimilation in step 1, in cases where full assimilation would yield a geminate. This reanalysis misses a broad, crosslinguistic generalization: Baković (2005) crucially shows that the features that epenthesis ignores for the sake of breaking up sufficiently similar segments are voicing and palatalization, the very same features that are involved in assimilation in the language. Baković shows that this property of identity avoidance—the features ignored for purposes of antigemination are those that assimilate independently in the language—holds across a significant variety of languages (see also Pająk and Baković 2010 for additional evidence from Polish on the tight relationship between assimilation and antigemination). Baković argues that the relationship between assimilation and antigemination is captured if con only includes Agree constraints, which drive assimilation, and NoGem, which drives antigemination where assimilation would result in a geminate. A reanalysis in terms of constraints against sequences like [pjbj] or [bbj] dismisses this generalization as coincidence.

5.3 Additional cases of a comparison of procedures

We briefly discuss other cases previously argued to be challenging for HS that can be characterized as involving a comparison of procedures. Stanton (2020) finds that the distribution of nasal clusters in Gurindji poses difficulties for HS under the assumption that nasal clusters spread nasality leftwards. In Gurindji (McConvell 1988), two nasal clusters cannot co-occur in a word; in the event that suffixation places two NCs together in a word, the later cluster denasalizes (/NC...NC/ → [NC...C]). Stanton’s analysis of these facts turns out to involve a comparison of procedures: nasality spreads leftwards from the following NC cluster (/kajira-mpal/ → [kãj̃ĩr̃ã-mpal] ‘across the north’), unless spreading results in a NCṼ cluster; in this case, the second NC is denasalized (/kankula-mpa/ → [kãnkula-pa], [*kãnkũl̃ã-mpa] ‘on the high ground’). Parallel OT can express this analysis because spreading through multiple segments takes place in a single step; the grammar can thus look ahead to see if the complete result would yield an NCṼ cluster. In HS, however, spreading is an iterative, multistep procedure (McCarthy 2011; Kimper 2011a), and so the NCṼ cluster will not be visible in the derivation until nasality has already begun spreading. An alternative analysis of these facts is that the alternation is long-distance nasal cluster dissimilation rather than nasal spreading—but see Stanton (2020) for several arguments against such an approach (including, for example, the fact that we do not observe other kinds of cluster dissimilation in the typology).

Finally, Anderson (2016) compares Parallel OT and HS with regard to how well they can capture the distribution of footing, metathesis, and syncope in Maltese data (Hume 1990). Maltese words demand right-aligned, disyllabic trochaic feet, with a heavy stressed syllable. In our terms, well-formed feet are built by comparing procedures: syncope occurs following footing to satisfy the aforementioned conditions on feet (/ji-bdil-u/ → (ˈji-b.di)l-u → (ˈji-b.dl-u) ‘they change’), but where syncope would result in a sonority reversal, CV-metathesis occurs as the next best option for satisfying these constraints (/ji-ʃrɔb-u/ → ji-ʃɔrb-u → ji-(ˈʃɔr.b-u); /ji-ʃrɔb-u/ → (ˈji-ʃ.rɔ)b-u → *(ˈji-ʃ.rb-u) ‘they drink’). Anderson finds that this is naturally expressed in Parallel OT, but is challenging for HS, which cannot look ahead to the full result of footing and syncope. Anderson assesses whether other serial analyses could capture the data involving monosyllabic feet or feet aligned to the right edge of the word at the beginning of the derivation, and suggests that each of these analyses is unworkable.

6 Conclusion and future directions

To summarize, we have argued that a variety of systems across languages, involving a diverse array of processes, are best understood to require lookahead in grammar. These cases each involve a comparison of procedures: apply one change followed by another unless the final result is dispreferred; in such a case, apply a different series of changes (or a single change, or none). The breadth of cases from Mohawk, Maragoli, Sino-Japanese, Lithuanian, Gurindji, and Maltese can be derived in Parallel OT but are recalcitrant in HS, as a result of requiring lookahead to the extent that whole procedures need to be compared. Apparent HS reanalyses of the cases we have compiled, such as those that have been posited previously and novel ones considered here, we argue either fail to capture the full set of data or miss important generalizations within or across languages. Given that a diverse array of processes can be involved in comparisons of procedures suggests that lookahead is not merely the reflex of a single phenomenon applying in parallel with others, but rather is a property of the grammar as a whole.

A few points of discussion are in order here. First, our argument for lookahead in grammar should be taken to pertain to processes that occur within the same morphosyntactic stratum (as in Stratal OT; e.g., Bermúdez-Otero 1999, 2003; Kiparsky 2000). Though certainly worth pursuing, we are agnostic to the question of whether cross-stratal lookahead is also necessary. Second, a reviewer appropriately cautions that OT suffers from a seeming overgeneration problem, in that it predicts the existence of bizarre and presently unattested patterns. These patterns are crucially generated as a result of permitting lookahead in grammar, but are avoided by serial frameworks that lack lookahead. One such pattern discussed in McCarthy (2006), for example, involves word-final deletion applying iteratively to vowels and obstruents until the word ends in a sonorant consonant (e.g., /palasanataka/ → [palasan]). Though we agree that the overgeneration problem must be addressed, we think that it cannot be taken to dismiss lookahead capability as a whole, considering the evidence presented throughout this article. Rather, we advocate for an alternative approach to the problem that is consistent with the view that grammar has lookahead: a theory that permits it so as to capture the attested patterns surveyed above using typologically well-motivated constraints, but that also rules out (or at least renders highly unlikely) bizarre and unattested patterns of lookahead, possibly by way of incorporating other independently motivated factors. This would inevitably involve a discussion about what kinds of lookahead patterns the theory should predict to exist, versus those that it should predict not to exist. This is a goal that we leave to future research.

Notes

See analyses of Mohawk stress in Michelson (1988, 1989), Potter (1994), Ikawa (1995), Piggott (1995), Hagstrom (1997), Rowicka (1998), Alderete (1999), Rawlins (2006), Houghton (2013), and Elfner (2016). We use the (1988) transcription system, but follow Michelson (1989), Rawlins (2006), and Elfner (2016) in leaving out allophonic processes like /h/ insertion before /rh/. [ʌ] and [u] are front and back nasal vowels, respectively, [y] a palatal glide, and [ts] an affricate.

We note that [e] does not break up [Cy] and [kw] sequences, despite them violating syllable contact when syllabified apart. In addition, [khy] is cited as a permitted word-initial CCC cluster (as in (6a)), and so epenthesis does not apply to break it up (Michelson 1988). We ultimately leave the extended analysis of Mohawk phonotactics to future research.

A reviewer asks if epenthesis could be reanalyzed as deletion. For example, we could say that the underlying form of the 1P morpheme is /wake/, surfacing faithfully in (/wake-nyak-s/, [wa.ˈken.yaks]) (9a) but undergoing hiatus-avoiding deletion in (/wake-aruʔtat-u/, [wa.ka.ruʔ.ˈtaː.tu]) (6b). This analysis is untenable, as it fails to resolve why [e] deletes even in non-hiatus-environments, where deletion would gratuitously violate syllable structure constraints. If /wake/ were underlying, for example, it would be difficult to explain why the final vowel deletes in e.g. [te.wak.ˈten.yu], *[te.wa.ke.ˈten.yu] (5c), in which no adjacent vowel can motivate hiatus repair. See Michelson (1988) for the complete argument.

We say ‘Step 1’ here for expository ease—in fact, we assume that epenthesis applied in a previous step. In Sect. 2.5, we consider an HS-based analysis of Mohawk that abandons the assumption that epenthesis precedes stress.

In order to properly assign violations to long epenthetic vowels, we assume that DepVː can compare the outputs of intermediate mappings to the underlying form. Otherwise, the analysis has no chance of succeeding. See Hauser et al. (2016) for a defense of faithfulness constraints in HS that compare outputs to underlying forms.

Note that *Non-HdFt/a must make the decision between (40a) and (40b), not Iamb, because AlignR must rank above Iamb to derive the choice of (ˈL.L) over antepenult (ˈH) when [e] occupies an open penult ([(ˈte.ke).riks], *[(ˈteː).ke.riks]).

We refer the reader to Rawlins (2006:32–36) for arguments against Alderete’s (1999) Parallel OT analysis of Mohawk based on HeadDep, and a defense of the approach we outline above, based on the avoidance of long epenthetic vowels. Data that challenge the HeadDep approach for Mohawk in particular involve both [e]-epenthesis (Rawlins 2006:32–33) and minimal word augmentation (Rawlins 2006:36 and Adler 2016:21–22). As it pertains to the latter, for example, avoidance of long epenthetic vowels explains why we see multiple epenthesis, rather than insertion of a long vowel, to resolve monosyllabism (e.g., /s-r-iht-Ø/ → [(ˈi.se)riht], *[(ˈse:)riht] 2A-cook-IMP). HeadDep cannot distinguish between these two alternatives (nor can even a tweaked version of HeadDep targeting open syllables exclusively, as a reviewer brings up). The analysis we adopt can capture the effects without appealing to this constraint. See Elfner (2016:263–265) for other arguments against HeadDep for the analysis of stress-epenthesis interactions.

In hiatus repairs in the language, the surviving vowel undergoes compensatory lengthening unless it is word-final. In the latter case, lengthening is blocked (e.g., (/vi-a/, [vja]) = agr8-of). In the data presented below, the vowel surviving hiatus repair is always final, so compensatory lengthening will play no role in the following discussion.

Prior investigators have enforced reduplicant heaviness either with a constraint that forces it to be heavy, or by specifying that the reduplicant is underlyingly heavy (see Hayes and Abad 1989 and McCarthy et al. 2012b on heavy reduplication in Ilokano, and Blevins 1996 on heavy reduplication in Mokilese—these investigators take one or the other approach). We are agnostic to which analytical choice is superior here, simply taking the latter approach. A merely apparent third alternative approach is to say that length is a remnant of compensatory lengthening following hiatus repair in the base. For example, we could envision the following schematic derivation for [jɔː-j-ɔ]: red-e-ɔ → red-j-ɔː (glide formation with compensatory lengthening) → jɔː-j-ɔː (copying) → jɔː-j-ɔ (final vowel shortening). But [viː-vj-ɔ] and like forms deriving from Ci- prefixes suggest this cannot be the right approach: the copy vowel is long, and yet does not derive from a base vowel that was lengthened at any point in the derivation.

The upcoming OT analysis sets aside certain minor complications in these data. In (/red-o-ɔ/, [wɔː-v-ɔ]), the base prefix undergoes vowel hardening, surfacing as [v] between vowels instead of [w], which can be accounted for with a constraint militating against certain [VwV] sequences (see Zymet 2018 for the analysis). In forms where a Co-prefix was copied (e.g., /red-go-ɔ/, [guː-gw-ɔ]), the reduplicant vowel always surfaces as high, even if the prefix is underlyingly mid. This can be accounted for with a constraint requiring the reduplicant vowel to match its corresponding stem glide for height (as in [guː\(_{\mathbf{1}}\)-g\(\mathbf{w}_{\mathbf{1}}\)-ɔ], *[goː\(_{\mathbf{1}}\)-g\(\mathbf{w}_{\mathbf{1}}\)-ɔ]; again, see Zymet 2018 for an analysis), or with a constraint against mid-tense vowels whose activity is only observed in environments that are not constrained by input-output faithfulness.

Though Onset would work just as well for our purposes, see Orie and Pulleyblank (1998) for an argument for NoHiatus in particular for handling hiatus repairs.

Furthermore, candidates such as *[v1ɔː3-v1j2-ɔ3] can be eliminated by a high-ranking constraint enforcing BR-contiguity (McCarthy and Prince 1995).

See Pająk and Baković (2010) for a similar pattern in Polish.

References

Adler, Jeffrey. 2016. The nature of conspiracy: Implications for parallel vs. serial derivation, Master’s Thesis, UC Santa Cruz. Rutgers Optimality Archive 1322.

Albright, Adam, and Edward Flemming. 2013. A note on parallel and serial derivations. Class notes. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Alderete, John. 1999. Head dependence in stress-epenthesis interaction. In The derivational residue in phonological Optimality Theory, eds. Ben Hermans and Marc van Oostendorp, 29–50. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Anderson, Skye. 2016. Obligatory parallel metathesis in Maltese? Poster presented at the Annual Meeting in Phonology 2016. Los Angeles, California: University of Southern California.

Ali, Azra, Mohamed Lahrouchi, and Michael Ingleby. 2008. Vowel epenthesis, acoustics and phonology patterns in Moroccan Arabic. Interspeech 2008, Brisbane, Australia, 1178–1181.

Baković, Eric. 2005. Antigemination, assimilation, and the determination of identity. Phonology 22(3): 279–315.

Bennett, Ryan. 2012. Foot-conditioned phonotactics and prosodic constituency. Santa Cruz dissertation, University of California

Bennett, Ryan. 2017. Output optimization in the Irish plural system. Journal of Linguistics 53(2): 229–277.

Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo. 1999. Constraint interaction in language change [Opacity and globality in phonological change]. PhD diss., University of Manchester and Universidad de Santiago de Compostela.

Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo. 2003. The acquisition of phonological opacity. In Variation within optimality theory: Proceedings of the Stockholm workshop on variation within optimality theory, eds. Jennifer Spenader, Anders Eriksson, and Östen Dahl, 25–36. Stockholm: Department of Linguistics, Stockholm University

Blevins, Juliette. 1996. Mokilese reduplication. Linguistic Inquiry 27(3): 523–530.

Broselow, Ellen. 2008. Stress-epenthesis interactions. In Rules, constraints, and phonological phenomena, eds. Andrew Nevins and Bert Vaux, 121–148. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Casali, Roderic. 1995. Patterns of glide formation in Niger-Congo: An optimality account. Paper presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, New Orleans.

Casali, Roderic. 1997. Vowel elision in hiatus contexts: which vowel goes? Language 73: 493–533.

Casali, Roderic. 1998. Resolving hiatus, New York & London: Garland. :.

Chomsky, Noam, and Morris Halle. 1968. The sound pattern of English. New York: Harper and Row.

Clements, George Nick. 1990. The role of the sonority cycle in core syllabification. In Papers in Laboratory Phonology I: Between the grammar and physics of speech, eds. John Kingston, and Mary Beckman Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, Stuart, and Seung-Hoon Shin. 1999. The syllable contact constraint in Korean: An optimality-theoretic analysis. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 8: 285–312.

de Lacy, Paul. 2006. Markedness: Reduction and preservation in phonology. Vol. 112 of Cambridge studies in linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Downing, Laura J., and Sharon Inkelas. 2015. What is reduplication? Typology and analysis part 2/2: The analysis of reduplication. Language and Linguistics Compass 9(12): 516–528.

Elfner, Emily. 2016. Stress-epenthesis interactions in harmonic serialism. In Harmonic grammar and harmonic serialism, eds. John J. McCarthy and Joe Pater, 261–300. Sheffield: Equinox Press.

Féry, Caroline. 1999. German word stress in optimality theory. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics.

Flack, Kathryn. 2009. Constraints on onsets and codas of words and phrases. Phonology 26(2): 269–302.

Gouskova, Maria. 2004. Relational hierarchies in OT: The case of syllable contact. Phonology 21(2): 201–250.

Gouskova, Maria, and Nancy Hall. 2009. Acoustics of unstressable vowels in Lebanese Arabic. In Phonological Argumentation. Essays on Evidence and Motivation, ed. Steve Parker, 203–225. London: Equinox.

Hagstrom, Paul. 1997. Contextual metrical invisibility. In MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 30. PF: Papers at the interface, eds. Benjamin Bruening, Yoonjung Kang, and Martha McGinnis, 113–181. Cambridge: Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hauser, Ivy, Coral Hughto, and Megan Somerday. 2016. Faith-UO: Counterfeeding in harmonic serialism. In Proceedings of the annual meeting on phonology 2014. Linguistic Society of America.

Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical stress theory: Principles and case studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayes, Bruce, and May Abad. 1989. Reduplication and syllabification in Ilokano. Lingua 77: 331–374.

Houghton, Paula. 2013. Switch languages: Theoretical consequence and empirical reality. PhD diss., Rutgers University.

Hume, Elizabeth. 1990. Metathesis in Maltese: Consequences for the strong morphemic plane hypothesis. North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 21: 157–172.

Ikawa, Hajime. 1995. On stress assignment, vowel-lengthening and epenthetic vowels in Mohawk and Selayarese: Some theoretical implications. In Arizona Phonology Conference (5); Proceedings of South Western optimality theory workshop; Coyote papers, Tucson: Department of Linguistics, University of Arizona.

Ito, Junko. 1986. Syllable theory in prosodic phonology. PhD diss., Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 1996. Stem and word in Sino-Japanese. In Phonological structure and language processing: Cross-linguistic studies, eds. Takashi Otake and Ann Cutler, 13–44. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2015. Sino-Japanese phonology. In Handbook of Japanese phonetics and phonology, ed. Haruo Kubozono, 290–312. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kawahara, Shigeto, Kohei Nishimura, and Hajime Ono. 2003. Unveiling the unmarkedness of Sino-Japanese. In Japanese/Korean Linguistics, Vol. 12, 140–151. Stanford: CSLI.

Kimper, Wendell. 2011a. Competing triggers: Transparency and opacity in vowel harmony. PhD diss., Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Kimper, Wendell. 2012. Harmony is myopic. Linguistic Inquiry 43(2): 301–309.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2000. Opacity and cyclicity. The Linguistic Review 17: 351–367.

Kurisu, Kazutaka. 2000. Richness of the base and root fusion in Sino-Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 9(2): 147–185.

Labrune, Laurence. 2012. The phonology of Japanese. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leung, E. 1991. The tonal phonology of Llogoori: A study of Llogoori verbs. In Working Papers of the Cornell Phonetics Laboratory, Vol. 6.

Lynch, John, and Rex Horoi. 2002. Arosi. In The Oceanic languages, eds. John Lynch, Malcolm Ross, and Terry Crowley, 562–572. Richmond: Curzon Press.

Mathangwane, Joyce T., and Larry Hyman. 1999. Meeussen’s rule at the phrase level in Kalanga. In African mosaic, ed. Rosalie Finlayson, 173–202.

McCarthy, John J. 2006. Restraint of analysis. In Wondering at the natural fecundity of things: Essays in honor of Alan Prince, eds. Eric Bakovic, Junko Ito, and John J. McCarthy, 213–239. Santa Cruz, CA: Linguistics Research Center.

McCarthy, John J. 2007. Slouching towards optimality: Coda reduction in OT-CC. In Phonological studies, ed. Phonological Society of Japan. Vol. 10, 89–104. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

McCarthy, John J. 2008. The serial interaction of stress and syncope. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 26(3): 499–546.

McCarthy, John J. 2010a. An introduction to Harmonic Serialism. Language and Linguistics Compass 4(10): 1001–1018.

McCarthy, John J. 2010b. Studying GEN. Journal of the Phonetic Society of Japan 13(2): 3–12.

McCarthy, John J. 2011. Autosegmental spreading in Optimality Theory. In Tones and features, eds. John A. Goldsmith, Elizabeth Hume, and W. Leo Wetzels. Berlin: de Gruyter.

McCarthy, John J. 2013. Irreducible parallelism and desirable serialism. Talk given at the annual meeting on phonology, 2013.

McCarthy, John J., Wendell Kimper, and Kevin Mullin. 2012a. Reduplication in Harmonic Serialism. Morphology 22(2): 172–232.

McCarthy, John J., Kevin Mullin, and Brian W. Smith. 2012b. Implications of harmonic serialism for lexical tone association. In Phonological explorations: Empirical, theoretical and diachronic issues, eds. Bert Botma, and Roland Noske, 265–297. Berlin: De Gruyter.

McCarthy, John. J., and Joe Pater. 2016. Harmonic grammar and harmonic serialism. London: Equinox Publishing.

McCarthy, John J., Joe Pater, and Kathryn Pruitt. 2016. Cross-level interactions in Harmonic Serialism. In Harmonic grammar and harmonic serialism, eds. John J. McCarthy and Joe Pater, 88–138. London: Equinox Publishing.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1986/1996. Prosodic Morphology. Vol. 13 of Linguistics Department Faculty Publication Series.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1993a. Generalized alignment. In Yearbook of morphology, eds. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle, 79–153. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1993b. Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and satisfaction, 482. Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science: Rutgers Optimality Archive.

McCarthy, John. J., and Alan Prince. 1994. The emergence of the unmarked. In North Eastern Linguistic Society (NELS 24), ed. Mercè Gonzàlez. Vol. 2, 333–379. Amherst: GLSA.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1995. Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In UMOP 18: Papers in optimality theory, eds. Jill Beckman, Suzanne Urbanczyk, and Laura Walsh Dickey, 249–384.

McConvell, Patrick. 1988. Nasal cluster dissimilation and constraints on phonological variables in Gurundji and related languages. Aboriginal linguistics 1: 135–165.

Mester, Armin. 1994. The quantitative trochee in Latin. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 12: 1–61.